Social phobia (or social anxiety disorder) consists of a marked and persistent fear of social or performance situations. Affected individuals fear that they will be evaluated negatively or that they will act in a humiliating or embarrassing way. Exposure to social or performance situations invariably leads to panic or marked anxiety, and such situations therefore tend to be avoided or endured with extreme distress.

Social phobia is the third most common mental disorder in adults worldwide, with a lifetime prevalence of at least 5% (depending on the threshold for distress and impairment). There is an equal gender ratio in treatment settings, but in catchment area surveys, there is a female preponderance of 3:2. Individuals are more likely to be unmarried and have a lower socio-economic status. Although common, social phobia is often not diagnosed or effectively treated. There have, however, been a number of developments in our understanding and treatment of social phobia over the past decade, and these are the focus of this article.

Presentation

The onset of social phobia usually takes place during adolescence, although a minority of causes involve a late onset after a significant life event (such as an episode of failure). The typical course is chronic and life-long. Predisposing factors include a shy or anxious temperament from childhood. There is significant comorbidity, especially of depression, alcohol or substance misuse or body dysmorphic disorder. In body dysmorphic disorder, patients are often too ashamed to reveal their preoccupation with their appearance, and present with symptoms of social anxiety and depression, fearing that the mental health professional will view them as vain or narcissistic. A similar situation exists in patients with olfactory reference syndrome, who believe that they have body odour that others will find unpleasant, which they may camouflage with perfume. Therefore, all patients with symptoms of social anxiety should be routinely asked whether they are very concerned about some aspect of their appearance or about body odour. It should be emphasised that patients with social phobia do not lack social skills. Most affected individuals will have normal social skills in a consultation with you, or with a friend or partner. In social situations, they are trying too hard and can appear to lack social skills, because they might interact less, keep their head down or not reveal personal information. Patients (for example, those with Asperger syndrome) who do lack communication skills have a different problem.

The presentation of social phobia can depend on cultural contexts. In Western cultures, patients might present to surgeons for cures for complaints of excessive blushing or sweating. In Japan, social phobia is manifested as an extreme fear of bringing offence to others, and is referred to as taijin kyofusho. Sufferers of this disorder may fear that making eye contact, blushing, imagined defects in their appearance or their body odour would be offensive to others.

Psychopathology

The core psychopathology in social phobia is a fear of negative evaluation in social and performance situations. It overlaps with the concept of shame, although the two sets of literature have largely ignored one other (Reference Gilbert and AndrewsGilbert & Andrews, 1998). Social anxiety is best described as the fear of feeling ashamed (e.g. of the emotions aroused and their interference in one's presentation) or the fear of being shamed (e.g. by the negative evaluation of oneself and potential loss of rank), or both.

Social phobia usually leads to avoidance of situations such as public speaking or talking to a group, parties, meetings, eating or drinking in public, working or writing while being observed, telephone calls, intimacy or dating. Groups are nearly always more anxiety-provoking than is an individual. Peers of the same age are usually more anxiety-provoking than older individuals. For heterosexual individuals, people of the opposite gender are usually more anxiety-provoking than those of the same gender. Sometimes individuals in authority, especially at work, are more anxiety-provoking than individuals at the same level.

There tend to be two sub-types of social phobia – generalised and non-generalised. Generalised social phobia is more disabling and involves a more diverse range of feared stimuli. Those affected by it include some patients with avoidant personality disorder and it has a worse prognosis. Non-generalised social phobia is associated with avoidance of a limited range of performance situations or interactions (such as public speaking), and this overlaps with performance anxiety in sexual dysfunction. Non-generalised social phobia is easier to treat, with a better prognosis.

A person afraid of speaking in public would not receive a diagnosis of social phobia if public speaking was not routinely encountered and the person was not particularly distressed about it. It is usually the degree of distress or impairment that warrants a diagnosis of social phobia, and the possible indicators need to be considered in the appropriate context. For example, transient or mild social anxiety is especially common in adolescence. The degree of severity in social phobia is very variable, ranging from individuals who are virtually housebound and have never had a relationship, to others who are highly functioning except in certain areas such as making a presentation, which they find very distressing and which handicaps them in their occupation.

Social phobia might be confused with agoraphobia. Individuals with agoraphobia tend to be female and to be anxious about their physical or mental health. They misinterpret physical sensations as evidence of an immediate catastrophe to their health. Panic attacks in agoraphobia tend to be both situational and spontaneous. Affected individuals are concerned with a wider range of autonomic sensations such as palpitations and feeling dizzy or short of breath. Those with social phobia, however, are more likely to be concerned with autonomic sensations of blushing, shaking or stammering (which the person believes may be noticeable to others). Panic attacks in social phobia occur almost exclusively in social situations. Sometimes, a patient with agoraphobia also has comorbid symptoms of social anxiety. For example, he might believe that he will collapse or go mad as a result of a panic attack, but in a social situation, he might also fear causing a scene and others evaluating him negatively. Typical beliefs in an individual with social phobia focus on the perceived negative evaluation by others of revealing a flaw or unacceptable behaviour (for example, the person believes that her hands will shake or she will sound stupid or boring). This is also referred to in the literature as ‘external shame’.

Such individuals tend to have high standards or rules about how they must perform in social situations. Their assumption is that failing to achieve these standards might lead others to see them as inferior, flawed or inadequate and they themselves also agree with this assessment (referred to as ‘internal shame’). They predict that this failure will lead to rejection or a further failure to achieve an important goal. Individuals with no internal shame may know that others are rejecting them and view them as inferior, but not believe it about themselves.

The emotions in social phobia are predominantly those of anxiety and shame, and sometimes self-disgust or anger (which will depend on beliefs and safety behaviours). As in other anxiety disorders, the main coping (or defensive) behaviour is to escape from the situation. There is a strong urge not to be seen. Eye gaze is commonly averted and there is behavioural inhibition (discussed in more detail below under ‘safety behaviours’). These behaviours might be linked to the submissive defensive behaviours used to reduce aggression in another person in response to the threat of rejection.

When the focus is on another person as being bad and doing something to expose the individual as inferior, then the main emotion is of humiliation (rather than social anxiety). There is a sense of injustice and unfairness, often leading to anger and a strong desire for revenge against the one who is exposing the self as weak or inferior.

Alcohol and other substances are commonly used in social phobia, but such usage might result in a self-fulfilling prophecy as patients may indeed make fools of themselves after excessive alcohol consumption. Although alcohol and substance dependence need to be treated first, many such patients will have difficulty attending self-help groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous. Nevertheless, mental health practitioners who treat alcohol and substance misuse frequently fail to address the comorbid social anxiety once the patient has stopped misusing and relapse is therefore common.

Assessment measures

Suitable assessment measures include the Brief Social Phobia Scale (Reference Davidson, Potts and RichichiDavidson et al, 1991) and the Social Anxiety Scale (Reference LiebowitzLiebowitz, 2002), which are both observer-rated. Subjective rating scales include the Social Phobia and Anxiety Scale (Reference Turner and BeidelTurner & Beidel, 1989), the Social Phobia Inventory (Reference Connor, Davidson and ChurchillConnor et al, 2000) and the Fear Questionnaire (Reference Marks and MathewsMarks & Mathews, 2002).

Graded self-exposure

Learning theory hypothesises that avoidance maintains the fear in social phobia, as patients are motivated to avoid ‘punishment’ by others. The anticipated ‘punishment’ – the prediction of rejection, deflation and isolation – is never disconfirmed. Graded self-exposure has been the treatment of choice for social phobia for many years. A detailed hierarchy is made of all the situations that the person avoids, with a rating of 0 to 100% according to the degree of anticipated anxiety. Self-exposure involves repeatedly facing previously avoided situations in a graded manner until habituation has occurred.

There are problems with exposure alone – for example, tasks might be brief (and not long enough for the anxiety to subside) or not susceptible to regular repetition. Furthermore, a significant number of patients refuse self-exposure or drop out early. Of those who complete treatment, about 50% will overcome their problem. Treatment failures tend to be associated with a depressed mood, avoidant personality, intolerance of emotion and marked avoidance behaviour. Alternative approaches have included group cognitive–behavioural therapy (Reference Heimberg, Dodge and HopeHeimberg et al, 1990) or the addition of coping skills, cognitive restructuring or shame-attacking from rational emotive behaviour therapy. An example of shame-attacking is for the patient to shout out the names of stations on a railway line. Other passengers might think that the individual is stupid, but he or she can learn that performing a stupid act does not make one stupid ‘through and through’. It is the affected individual's own evaluation of his or her behaviour that is crucial in determining the degree of social anxiety. Such alternative approaches are not usually recommended, as adherence is likely to be poor unless the therapist is prepared to model the behaviour. Self-exposure and variants of cognitive restructuring are effective and valid treatments, but the treatment gains might only be modest. For example, Reference Heimberg, Dodge and HopeHeimberg et al(1990) report that only 65% make ‘clinically significant change’.

Cognitive therapy

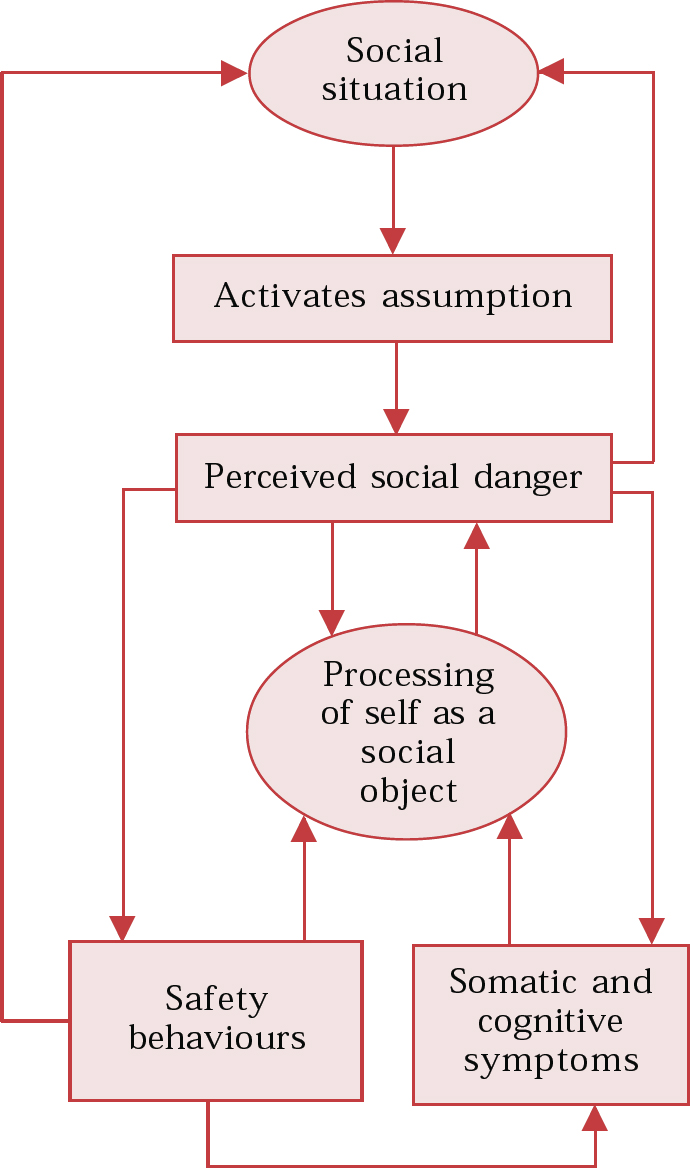

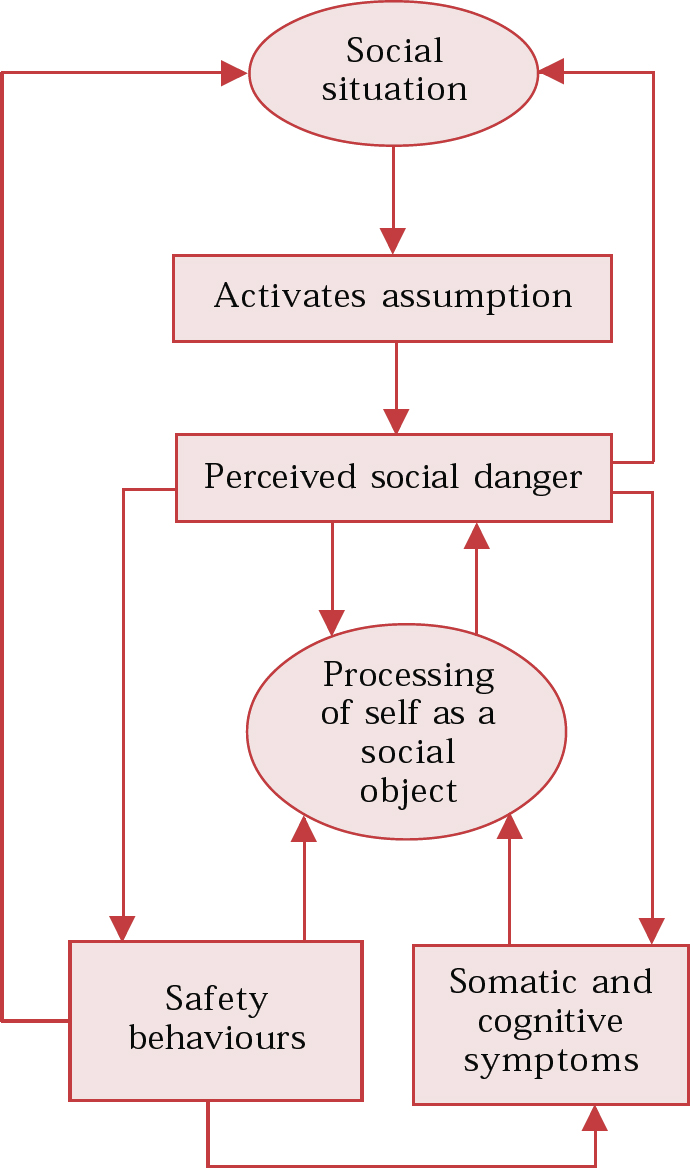

Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz and HopeClark & Wells (1995) and Reference Clark, Crozier and AldenClark (2001) have developed a cognitive model for the maintenance of social phobia (Fig. 1). Most of the material for the rest of this article is derived from their approach. The aim of the model is to answer the question of why the fears of someone with social phobia are maintained despite frequent exposure to social or public situations and the non-occurrence of the feared catastrophes. Recent research from controlled trials supports the efficacy of the approach (Reference Clark, Ehlers and HackmannClark et al, 2003). The model suggests that when patients enter a social situation, certain rules (e.g. ‘I must always appear witty and intelligent’), assumptions (e.g. ‘If a woman really gets to know me then she will think I am worthless’) or unconditional beliefs (e.g. ‘I'm weird and boring’) are activated. When individuals believe that they are in danger of negative evaluation, an attentional shift occurs towards detailed self-observation, and monitoring of sensations and images. Socially anxious individuals thus use internal information to infer how others are evaluating them (in Fig. 1 this is ‘processing of self as a social object’). The internal information is associated with feeling anxious, and vivid or distorted images are imagined from an observer perspective (Reference Hackmann, Clark and McManusHackmann et al, 2000). These images are mostly visual, but they might also include bodily sensations and auditory or olfactory perspectives. This is not, of course, what an observer actually ‘sees’. Recurrent images can be elicited by asking patients to recall a social situation associated with extreme anxiety. The images are usually linked to early memories. The therapist asks the patient when he or she remembers first having the experience encapsulated in the recurrent image and to recall the sensory features and meaning that these had. For example, someone who had an image of being fat remembered being teased during adolescence, which resulted at the time in feelings of humiliation and rejection.

Fig. 1 A model of social phobia.

A second factor that maintains symptoms of social phobia are safety behaviours. These are actions taken in feared situations which are designed to prevent feared catastrophes (Reference SalkovskisSalkovskis, 1991). Safety behaviours in social phobia include: using alcohol; avoiding eye contact; gripping a glass too tightly; excessive rehearsing of a presentation; reluctance to reveal personal information; and asking many questions. Safety behaviours are often problematic: they prevent disconfirmation of the feared catastrophe; they can heighten self-focused attention and monitoring to determine if the behaviour is ‘working’; they increase the feared symptoms (e.g., keeping arms close to the body to stop others seeing one sweat will increase sweating); they have an effect on others (e.g. the individual may appear cold and unfriendly, so that a feared catastrophe becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy); and they can draw attention to feared symptoms (e.g. speaking quietly and slowly will lead others to focus on the individual even more).

It is hypothesised that a third factor that maintains symptoms of social phobia is anticipatory and post-event processing. Such processing focuses on the feelings and constructed images of the self in the event and leads to selective retrieval of past failures.

Stages of therapy

Therapy begins with a detailed assessment and formulation of the problem, which is developed collaboratively between therapist and patient. The aim is to understand the development and maintenance of the disorder and how the patient's current beliefs, emotions and behaviour interact. Sessions are recorded on audio- or videocassette so that the patient may listen to a session again and provide feedback at the next session. The therapist also has an opportunity of reviewing the sessions in supervision.

An idiosyncratic version of the model (Fig. 1) is drawn up with the patient, based upon a review of recent episodes of social anxiety. First, the therapist identifies a specific and recent social situation that was sufficiently anxiety-provoking. He or she then attempts to identify the negative automatic thoughts by asking questions such as: ‘What went through your mind as you noticed yourself becoming anxious’, ‘What was the worst you thought could happen?’ and ‘What did you suppose that others would notice or think?’

The therapist may use a ‘downward arrow’ technique to try to identify the patients’ assumptions and core beliefs. This involves asking the patient to assume the worst and then to assume that the thought is true. The therapist then asks what the most anxiety-provoking thing about the thought is or what it means to the individual. For example:

Therapist: How did you feel you came across?

Patient: I felt I appeared very red and sounded stupid.

Therapist: Let's assume that you did appear very red and sounded stupid, what would that mean about you?

Patient: I felt that I looked like an idiot and others would be secretly laughing at me.

Therapist: Let's assume it's true that everyone in the room is laughing to themselves, what would that mean to you?

Patient: I think no one will really want to know me in the future and I'll be alone.

Next, the therapist identifies the autonomic sensations or symptoms of anxiety by asking questions such as: ‘When you thought the feared event might happen, what did you notice happening in your body?’ (e.g. blushing, shaking, sweating).

Safety behaviours are next elicited by asking ‘When you thought the feared event might happen, did you do anything to try to prevent it from happening?’, ‘Is there anything you do to try to ensure you come across well?’ or ‘Do you do anything to stop drawing attention to yourself?’

Increased self-consciousness and imagery are elicited by asking questions such as: ‘What happens to your attention when you are most afraid? Do you become more self-conscious? Do you have difficulty following what others are saying? Do you have a picture in your mind of how you feel you are coming across?’ Further details of the imagery are elicited and of whether it takes an observer perspective.

The model may then be used to determine its potential application to past and present experiences and how each of the components is linked to a feedback loop. It is particularly important to review how increased self-focused attention and using safety behaviours are counterproductive, and increase the frequency of the thoughts and anxiety. Once a patient is engaged in the model, then various strategies may be used to consolidate understanding and to make changes in the system.

Shifting attentional focus

The aim of shifting attentional focus is to enable patients to concentrate on how others respond to them, rather than on constructed images or impressions of how they think they appear. A role-play is done, in which the focus of attention is manipulated in order to demonstrate the adverse effect of self-focused attention and safety behaviours. The patient is asked to compare the degree and content of self-consciousness, subjective anxiety and whether the self is still in an observer perspective.

Readers may like to try this for themselves, to begin to understand the strategies used by someone who is socially anxious. Test out two different scenarios with a colleague. For the first scenario, demand a high standard from yourself that you must appear extremely witty and intelligent in the conversation with your colleague and throughout your conversation, focus your attention on how you are feeling and observe the impression that you think you are making (looking at yourself from an observer's perspective). You should monitor whether you are coming across as extremely witty and intelligent. For the second scenario, reduce your expectations about being witty and intelligent and focus your attention wholly on the way that your colleague responds. After the role-play, it is time to receive feedback on your performance from your colleague and reflect on how hard it is to monitor yourself in self-focused attention. Homework might focus on an exercise in dropping of safety behaviours and shifting attentional focus in a social situation. This might then be followed with more traditional tasks of graded exposure, but without safety behaviours.

Other researchers have developed more elaborate strategies, such as Task Concentration Training for shifting attentional focus (Reference Bogels, Mulkens and De JongBogels et al, 1997). This is a technique that aims specifically at redirecting the affected individual's attention away from anxiety and internal sensations such as blushing, trembling, sweating or imagery, and towards the social task at hand and relevant environmental aspects. The training consists of three phases: first, getting insight in attentional processes and the effects of heightened self-focused attention; second, focusing attention outward in non-threatening situations; and third, focusing attention outward in threatening situations.

Video feedback

The aim of video feedback is to demonstrate that the patients’ impressions of how they think they appear are inaccurate and based on their internal images and feelings. For example, a patient may make a prediction about how red he appears when he blushes. An experiment may be set up, whereby he selects the predicted ‘redness’ on a colour chart and compares this with the actual ‘redness’ of his blushing on a video with the colour chart in the background. This approach is also suitable for any reaction that can be objectively observed on a video and compared against an agreed reference point.

Modifying negative self-images

Self-images might be associated with negative memories from childhood or adolescence. For example, the image and memories might be of being teased and isolated from one's peers. Therapy may be directed at historical reviews of such images (Reference Arntz and WeertmanArntz & Weertman, 1999), and referring to them as being ‘ghosts from the past’ that have not yet been updated. Therapy is therefore aimed at modifying the images or changing them in line with current reality.

Modifying assumptions and core beliefs

Modifying of assumptions and core beliefs in social phobia is no different from that in standard cognitive therapy. However, a key strategy is to make predictions and test out assumptions in behavioural experiments. This may involve ‘exposure’ to social situations, but it does not involve repeated exposure and a model of habituation. The emphasis is on shifting the focus of attention, dropping safety behaviours, processing the situation (not the self) and evaluating what was predicted against what actually happened. For example, an individual with social phobia who fears that she may behave in an unacceptable manner would be encouraged to behave ‘unacceptably’, perhaps by making pauses in her speech, having damp armpits, expressing an opinion or spilling her drink, and to observe another's response. Alternatively, a survey could be conducted to find how unacceptable these behaviours are to others and what the consequences might be.

Modifying post-interaction ruminations

Those affected by social phobia often engage in ‘post-mortems’. Here, the therapist helps the patient to identify the content of the event (not the feelings) and review what actually happened by shifting to external processing and constructing an alternative data log of information that is normally disregarded or distorted.

Therapy would normally take between 8 and 20 out-patient sessions, depending on the severity and chronicity of the phobia. Patients with very severe phobia, who are housebound or dependent on alcohol, might do better on an intensive programme of CBT as either day-patients or in-patients in the right setting.

Pharmacotherapy

Medication is indicated if it is the patient's first choice, CBT has failed, there is a long waiting-list for CBT or there is significant comorbidity of depression. The treatment of choice in social phobia is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) (Reference Ballenger, Davidson and LecrubierBallenger et al, 1998). Of the SSRIs, only paroxetine is licensed and marketed in the UK for social phobia, although there is no reason why other SSRIs may not be as effective. Most affected individuals can tolerate a normal starting dose of an SSRI, as they do not usually experience an ‘activation syndrome’ (as in panic disorder). The starting dose is used for 2–4 weeks and then increased as necessary. The onset of action is usually within 6 weeks and an adequate trial period is 8 weeks. The full response may occur after up to 12 weeks.

About 50% of patients relapse on discontinuation of an SSRI and treatment is therefore continued for a minimum of 12 months. Once in remission, the dose may be reduced slowly (e.g. a 25% reduction every 2 months). If a patient fails to respond to an SSRI, then some evidence exists for the efficacy of a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) (e.g. phenelzine, 45– 90 mg daily) or a reversible monoamine oxidase inhibitor (RIMA) (e.g. moclobemide, 300–900 mg daily). Allow 2 weeks between discontinuing an SSRI (5 weeks if fluoxetine) and commencing an MAOI or RIMA. Although there are no evidence-based guidelines on the treatment of patients who have failed to respond fully to an SSRI or an MAOI, expert opinions suggest the adjunctive use of beta-blockers (e.g. propranolol, starting dose 20 mg daily, gradually increased to 60 mg, or atenolol 50–100 mg daily) to augment the response. Similarly, clonidine may augment the response for symptoms of blushing when used as an adjunct to an SSRI. The use of benzodiazepines (especially short-acting ones) is not recommended, because side-effects at a higher dose can include sedation, forgetfulness, impaired concentration and disinhibition, especially when used intermittently. Benzodiazepines are especially contraindicated for patients with comorbidity of depression and/or a history of alcohol or substance misuse.

Which treatment for whom?

Only one trial has compared later versions of CBT with an SSRI (Reference Clark, Ehlers and HackmannClark et al, 2003), and it found CBT to be superior to fluoxetine. No trials have yet compared later versions of CBT with a combination of CBT and another SSRI, especially in the long term and after discontinuation of the active treatment. As always, treatment will depend upon patient choice and availability of therapy, but in common with other anxiety disorders, CBT is the initial choice of treatment for social phobia, as it is usually more acceptable and has a reduced risk of relapse. As always, the main problem is user choice and access to CBT in a timely manner.

Multiple choice questions

-

1 Individuals with social phobia:

-

a experience an image from a field perspective (i.e. as looking out from their own eyes)

-

b lack social skills

-

c avoid social situations to prevent negative evaluation

-

d focus on the perceived negative evaluation of a revealing flaw or unacceptable behaviour

-

e may assume they will be rejected or fail to achieve important goal.

-

-

2 Social phobia:

-

a is the third most common mental disorder in adults

-

b has a lifetime prevalence rate of about 10%

-

c occurs more frequently in males than females in psychiatric clinics

-

d has significant comorbidity with depression, and substance misuse

-

e is more likely to occur among unmarried individuals with a lower socio-economic status

-

-

3 In cognitive therapy of social phobia:

-

a fluoxetine was found to be more effective than CBT

-

b the aim of shifting attentional focus is to enable patients to concentrate on how they think they appear to others

-

c the aim of video feedback is to demonstrate that the patient's impressions of how they think they appear are inaccurate and based on internal images and feelings

-

d behavioural experiments are used to make predictions which are then tested

-

e social skills training is provided.

-

-

4 In the presentation of social phobia:

-

a onset is gradual during adolescence

-

b the typical course is chronic and life-long

-

c predisposing factors include a shy or anxious temperament from childhood

-

d a minority are of late onset after a significant life event

-

e panic often occurs when alone.

-

-

5 In pharmacotherapy for social phobia:

-

a an SSRI should usually be commenced at a lower dose than that used for depression

-

b the full response occurs in about 6 weeks

-

c an alternative to an SSRI is an MAOI

-

d short-acting benzodiazepines are recommended

-

e beta-blockers may be helpful as initial treatment of choice.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

| a | F | a | T | a | F | a | T | a | F |

| b | F | b | F | b | F | b | T | b | F |

| c | T | c | F | c | T | c | T | c | T |

| d | T | d | T | d | T | d | T | d | F |

| e | T | e | T | e | F | e | F | e | F |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.