Introduction

In recent times, some politicians from the radical right in Europe increasingly have attempted to tie economic issues such as trade to issues on immigration. For instance, Marine Le Pen, the leader of the Front National (FN), put forth a policy package combining an increase in trade barriers and a clampdown on immigration during the 2017 French presidential elections. In an interview with Niek Stam, a leader of the FNV Haven labor union in Rotterdam, Champion and Van Der Schoot (Reference Champion and Van Der Schoot2017) revealed that economic fears over unemployment due to automation potentially fuelled opposition toward immigration, and consequently, support for the Dutch Party for Freedom, which campaigned for a crackdown on immigration.

A question these events raise is: are concerns over economic issues increasingly correlated with opposition toward immigration? As Malhotra et al. (Reference Malhotra, Margalit and Mo2013) noted, existing studies on attitudes toward immigration tend to focus on two sources – economic and cultural. Scholars who argue that economic considerations drive opposition to immigration generally refer to labor market competition effects, such as suppressed wages or competition over jobs associated with an increase in immigrant workers (e.g., Scheve and Slaughter, Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001; Mayda, Reference Mayda2006; Dancygier and Walter, Reference Dancygier, Walter, Pablo Beramendi, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015). By contrast, scholars who emphasize cultural factors generally argue that immigrants are perceived as a potential threat to existing traditions and the collective identity of the natives (e.g., Hainmueller and Hiscox, Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2007; Kinder and Kam, Reference Kinder and Kam2009).

Broadly speaking, the effects of economic considerations appear to be more contested than cultural considerations (Hainmueller and Hiscox, Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2010). Recent studies, using more sophisticated measures than before, have however shown that immigration attitudes might have objective economic foundations. For example, Ortega and Polavieja (Reference Ortega and Polavieja2012) and Polavieja (Reference Polavieja2016) found that occupational characteristics such as the relative manual and communicational intensity of a workerʼs occupation and job-specific human capital are significant determinants of attitudes toward immigration. Their work suggests that labor market competition with immigrant workers cannot be overruled as a major driver for opposition to immigration.

Another approach ties opposition to immigration to dwindling economic prospects, irrespective of whether poorer economic prospects are a direct result of immigration or not (Geraci et al., Reference Geraci, Kaiser and Thewissen2017, see also Colantone and Stanig, Reference Colantone and Stanig2018 for an analysis on Brexit). This line of reasoning contends that migration, technological change, and trade all involve labor market risks, but for the grand majority of people, the exact mechanisms through which these risks manifest themselves are rather unclear. Individuals might blame immigration because they misattribute the causes of their labor market risks or just simply channel their status anxiety into issues that are more easily controlled. Geraci et al. (Reference Geraci, Kaiser and Thewissen2017) argued that people may perceive governments as powerless to control technological change and economic globalization, but have more ability to limit migration. Put together, this perspective suggests that changes in economic prospects caused by economic shocks could affect opposition toward immigration, even if there is no direct labor market competition.

The complicated relationship between labor market risks and preferences has been studied extensively in the sociological and political economy literature (e.g., Iversen and Soskice, Reference Iversen and Soskice2001; Kitschelt and Rehm, Reference Kitschelt and Rehm2014), but less so in studies focusing on immigration attitudes. In this broader literature, labor market risks are frequently examined at the occupational level, based on the idea that occupational hazards, such as the likelihood of facing unemployment and the costs and difficulties of regaining employment, influence peopleʼs preferences. In principle, adopting an occupational approach also entails accepting the intertemporal element of self-interest. More specifically, the link between preferences and economic considerations is not necessarily limited to current income or labor market status, but may include future income associated with labor market risks and prospects (e.g., Geraci et al., Reference Geraci, Kaiser and Thewissen2017; Thewissen and Rueda, Reference Thewissen and Rueda2019).

Our paper contributes to this literature of labor market risks and prospects by looking at whether and how occupational characteristics are linked with immigration attitudes. More specifically, we apply the task approach (Autor et al., Reference Autor, Levy and Murnane2003; Acemoglu and Autor, Reference Acemoglu and Autor2011) to test whether workers who are most vulnerable to technological change and offshoring are most anti-immigrant. We argue that occupational task routineness is associated with more negative views on immigration, whereas occupational offshorability has an opposite and more heterogeneous effect. The differences in immigration attitudes between workers in offshorable occupations are much more polarized than of those in non-offshorable occupations.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. First, we review the literature on the causes and implications of the job polarization that has taken place in Western Europe in the last few decades and how these changes affect workers in different occupations. Second, we argue that the link between technological change and offshoring depends on comparative advantage, especially at the occupational level. We also discuss how these labor market risks are associated with attitudes toward immigration. Next, we introduce our hypothesis, data, empirical strategy, and results. The final section concludes.

Job polarization and the changing nature of international trade

To fully understand the significance of the two focal points of this paper – occupational task routineness and offshorability – we need to recognize how profoundly technological change and offshoring have shaped the European labor market structures in recent decades. In their influential paper, Goos et al. (Reference Goos, Manning and Salomons2014) provided evidence on how the growth rates of different occupations have varied greatly in Western Europe between 1993 and 2010. They noted that job growth has been concentrated not only in high-paid jobs such as professionals and managersbut also in low-paid jobs such as personal service, transport, and sales workers. By contrast, middling jobs such as craft workers, machine operators, and office clerks have seen relative declines.

Building on the task approach (Autor et al., Reference Autor, Levy and Murnane2003; Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg, Reference Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg2008; Acemoglu and Autor, Reference Acemoglu and Autor2011; Autor, Reference Autor2013), the authors observed that job growth has been analogous to the routine intensity of occupations. There has been a substantial increase in the employment of occupations that include mainly nonroutine tasks, but decline in the employment of occupations characterized by routine tasks. While the main cause of the witnessed job polarization is technological change, offshoring of routine work to countries with lower production costs is also accountable for the decline in the number of routine occupations. Together, technological change and offshoring can account for about three quarters of the witnessed job polarization in Western Europe (Goos et al., Reference Goos, Manning and Salomons2014).

Put simply, job polarization means divergence of employment opportunities and labor market risks between worker groups. Workers in occupations, whose tasks can be partly or fully replaced by a machine or a computer, are most vulnerable to technological change. However, to assess vulnerability to offshoring, it is essential to understand the changing nature and heterogeneous effects of international trade.

Traditional trade theories focus on comparative advantage at the level of sectors (Ricardo-Viner (RV) models) or at the level of factors of production (Stolper-Samuelson models). In the former (RV), the distributive conflict takes place at the level of industries. From this perspective, the labor market effects of international trade, and correspondingly the economic risks facing different groups of workers, is dependent on (a) the industries these workers belong to and (b) the extent of comparative advantage these industries enjoy in advanced economies (e.g., Gourevitch, Reference Gourevitch1986; Walter, Reference Walter2017). In the latter (SS), the effects of trade occur at the level of factors of production and are distributed according to the skill level of individual workers. Trade increases relative returns to a countryʼs abundant factors and relative fall in returns to scarce factors. As advanced economies are abundant with skilled labor, the model predicts that skilled workers benefit from trade, whereas the unskilled workers face more economic hardships in these countries (Feenstra and Hanson, Reference Feenstra and Hanson1999; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Dancygier and Walter, Reference Dancygier, Walter, Pablo Beramendi, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015).

While micro-level studies have given partial support for both of the traditional theories (Dancygier and Walter, Reference Dancygier, Walter, Pablo Beramendi, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015), their explanatory power has been increasingly questioned for several reasons. First, empirical firm-level research has provided evidence of substantial within-industry variation in productivity and wage levels, which is neglected in sectoral models (Walter, Reference Walter2017). Second, there is considerable heterogeneity in the distributional consequences of trade even among workers with nominally the same skill levels (Walter, Reference Walter2017; Rodrik, Reference Rodrik2018), which is contrary to what factor-endowment models predict. Third and most importantly, trade today takes place in a world of, and increasingly, fragmented production chains, which crosscut industrial sectors and skill-specific factors. As bits of value are being added in many different locations, trade is better characterized as ‘trade in tasks’ instead of trade in final goods and services (Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg, Reference Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg2008, p. 1978.). For instance, an Apple iPhone is designed in the USA, with its components sourced from different suppliers produced in Japan and South Korea and finally assembled in China before being exported to the test of the world (The Economist, 2011).

The new trade models that study the heterogeneous labor market consequences of trade at the occupational level build on the task approach (Autor et al., Reference Autor, Levy and Murnane2003; Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg, Reference Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg2008) and are thus arguably better suited for analysing trade in the setting of fragmented production chains. Since each occupation consists of a bundle of tasks (Owen and Johnston, Reference Owen and Johnston2017; Frey and Osborne, Reference Frey and Osborne2017) of which each occupationʼs task structure is largely different from another occupationʼs, a trade in task approach suggests that the effects of international trade are distributed at the level of occupations. The approach acknowledges that people move across occupations, but relaxes the assumption of full labor mobility, since there are costs and hurdles associated with changing jobs (Ritter, Reference Ritter2014; Owen and Johnston, Reference Owen and Johnston2017). Some occupations require licensing and accreditation and others long occupational tenure (Kambourov and Manovskii, Reference Kambourov and Manovskii2008). Because human capital is to some degree skill-specific, skills are not easily transferable between occupations (Kambourov and Manovskii, Reference Kambourov and Manovskii2009). Changing an occupation destroys occupation-specific human capital (Ritter, Reference Ritter2014), which may push workers either to occupations with lower wage or to occupations, which have comparatively similar task content to the previous occupation.

The occupational approach suggests that the effects of international trade crosscut industrial sectors and skill-specific factors. The key takeaway in terms of distributional conflict is that the occupational task content determines whether and how individuals benefit from or are hurt by trade. In countries that have comparative advantage in routine production, trade should benefit people in routine-intensive occupations. Correspondingly, in countries that have comparative advantage in abstract and cognitive tasks – such as the advanced capitalist countries of Western Europe – trade in tasks should benefit people in nonroutine occupations (Owen and Johnston, Reference Owen and Johnston2017).

Occupational threat of technological change and offshoring

Whether or not an individual is vulnerable to technological change and offshoring can be studied by looking at her/his job characteristics, more specifically the routine task content and offshorability of the occupation. Task routineness measures how easily a task can be replaced by technology, and offshorability quantifies how easily a task can be provided from abroad. These characteristics are not fixed over time, since technological advances change the task content of occupations. Therefore, they should not be considered as precise measures of labor market risks that actualize when a certain level is exceeded. Rather, they function as proxies for occupational threat of unemployment, which in turn may affect wages and job descriptions whether or not the technological displacement of jobs or offshoring actually takes place.

In their seminal work, Autor et al. (Reference Autor, Levy and Murnane2003) suggested that routine tasks are more likely to be replaced by technology than nonroutine tasks, because computers and automation can substitute for tasks, which are well defined, limited, and follow explicit rules, but are complements for tasks, which involve a lot of problem solving and complex communication. Routine tasks include typically activities such as calculation, repetitive customer service, record keeping, picking and sorting, and repetitive assembly. By contrast, nonroutine tasks require creativity, persuasion hypothesis formation, but may also require physical flexibility, adaptability, and visual recognition (Autor et al., Reference Autor, Levy and Murnane2003; Acemoglu and Autor, Reference Acemoglu and Autor2011; Autor, Reference Autor2013). To illustrate, routine tasks are typically abundant in occupations such as office clerks and machine operators, while nonroutine tasks are typical in occupations such as professionals, personal service workers, and drivers.

Conceptually, the approach depends crucially on differentiating tasks and skills, as well as reconceptualizing occupations. Tasks here need to be understood as ‘units of work activity that produce output’ while skills refer to a ‘workerʼs stock of capabilities for performing various tasks’ (Autor, Reference Autor2013). Another key difference is that skills measure human capital, which is largely acquired before entering the labor market, whereas tasks are an integral part of job descriptions. While many nonroutine tasks require high skill and many routine tasks do not, there is no systematic link between skills and tasks (Acemoglu and Autor, Reference Acemoglu and Autor2011). Especially the nonroutine tasks include occupations that require very high skill (e.g., professors) and occupations that are low-skill intensive (e.g., cleaners).

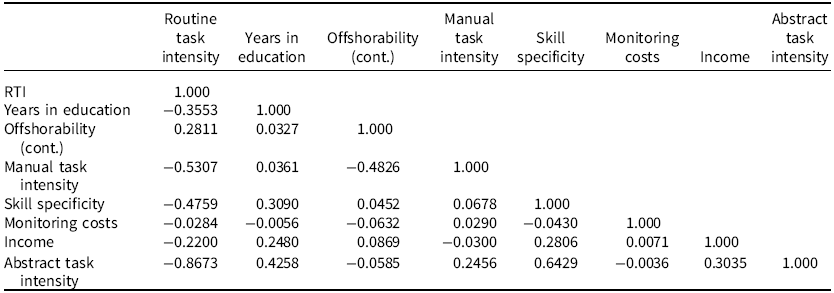

Occupational offshorability in turn (Blinder, Reference Blinder2009; Blinder and Krueger, Reference Blinder and Krueger2013) measures the degree to which a task can be provided from abroad. The key determinants of occupational offshorability are whether the occupation (1) requires a specific location (miners, cleaners, taxi drivers) and whether it (2) requires face-to-face interaction (childcare workers, management). While offshorability is often associated with routine tasks, this is not always the case. For example, the work of physical, mathematical, and engineering professionals involves many nonroutine tasks, but is rather easy to offshore (Goos et al., Reference Goos, Manning and Salomons2014). The most-offshorable jobs are not automatically low-end jobs (Blinder, Reference Blinder2009). In our data, the correlation between years in education and offshorability is close to zero (see Appendix Table A1).

Occupations that contain a high degree of offshorable tasks are open to global competition, whereas non-offshorable occupations face only domestic competition. However, there is a crucial difference between being able to offshore a job and actually doing so (Owen and Johnston, Reference Owen and Johnston2017). An important characteristic of an offshorable occupation in terms of labor market vulnerability is that it is also potentially onshorable to the home country. This denotes that workers may actually benefit from offshorability through the onshoring of tasks and the extended production of exported goods and services intensive in these tasks (Owen and Johnston, Reference Owen and Johnston2017). For example, the jobs (and tasks) of economists, engineers, and financial analysts could potentially be offshored from advanced economies, but it is implausible that this will actually happen as long as the workers in these occupations are more productive in performing their tasks than the workers in other countries. On the contrary, these workers are likely to benefit from international trade as the demand of their skills increases. The opposite is true for workers in occupations whose task routine and offshorability is high (e.g., metal moulders, call center assistants, assembly line workers). These workers are less able to shield from global competition, because routine tasks that require only low or medium skill are particularly easily copied by workers elsewhere (Ebenstein et al., Reference Ebenstein, Harrison, McMillan and Phillips2014).

To sum up, wage and employment effects of offshoring vary across task characteristics. Low- and medium-skilled workers in routine occupations are most likely to suffer from offshoring, whereas skilled workers in nonroutine occupations enjoy positive wage and employment effects (Hummels et al., Reference Hummels, Jørgensen, Munch and Xiang2014; Owen and Johnston, Reference Owen and Johnston2017).

Economic vulnerability and opposition to immigration

Existing studies show that economic vulnerability impacts political preferences (Rehm, Reference Rehm2009; Rovny and Rovny, Reference Rovny and Rovny2017; Thewissen and Rueda, Reference Thewissen and Rueda2019; Im et al., Reference Im, Mayer, Palier and Rovny2019). We follow these studies and conceptualize economic vulnerability as the risk of becoming unemployed (Rehm, Reference Rehm2009; Schwander and Häusermann, Reference Schwander and Häusermann2013; Im et al., Reference Im, Mayer, Palier and Rovny2019). Unemployment risks vary greatly by occupational characteristics. Economically vulnerable workers experience a high risk of becoming unemployed (Rovny and Rovny, Reference Rovny and Rovny2017). For instance, lawyers have much lower chances of losing their jobs than factory-floor workers, because technological change, international trade, and immigration increase the relative demand for the skills of the former, but reduce the demand for the skills of the latter.

Economic vulnerability influences workers’ issue opinions. They may prefer policies which restrict the scope and scale of economic change and limit their declining economic prospects. For example, economically vulnerable workers may favor protectionist trade policies (Owen and Johnston, Reference Owen and Johnston2017; Walter, Reference Walter2017). In the same vein, economically vulnerable workers may also favor social policies, which mitigate the negative effects of economic change. They may thus support more income redistributionand less workfare (Rehm, Reference Rehm2009; Fossati, Reference Fossati2018; Thewissen and Rueda, Reference Thewissen and Rueda2019).

Economically vulnerable workers may also oppose immigration for two reasons. Firstly, foreign-born workers may affect economically vulnerable workers’ economic prospects when they compete with native-born workers for employment. This form of labor market competition is more likely to occur in occupations where foreign-born workers have a comparative advantage over native-born workers (Dancygier and Walter, Reference Dancygier, Walter, Pablo Beramendi, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015). Secondly, economically vulnerable workers may oppose immigration because they require social protection to alleviate income loss during unemployment. Because immigrants are more frequently nonemployed and more reliant on social protection than the native population, individuals in economically vulnerable positions are more concerned about welfare competition from immigrants (van Oorschot, Reference Van Ooorschot2006; van Oorschot and Uunk, Reference Van Oorschot and Uunk2007). Such workers are therefore more likely to prefer ‘stricter conditionality in welfare rationing to prevent social protection from being used by competing groups’ (van Oorschot and Uunk, Reference Van Oorschot and Uunk2007, p. 65) such as immigrants. Such workers may thus also oppose immigration on the grounds of welfare competition (Bornschier and Kriesi, Reference Bornschier, Kriesi and Rydgren2012; Hochschild, Reference Hochschild2016).

Even if economically vulnerable workers do not face substantial labor market or welfare competition from immigrants, they may nevertheless still oppose immigration owing to radical right parties’ discourse. Economically vulnerable workers are a substantial part of radical right parties’ electorates (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Mayer, Reference Mayer and BRACONNIER2015). To appeal to such workers, they frequently refer to a nostalgic ‘better’ past prior to economic and societal upheavals (Gidron and Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2017; Gest et al., Reference Gest, Reny and Mayer2018; Im et al., Reference Im, Mayer, Palier and Rovny2019). Their discourse frequently blames processes such as international trade, European enlargement, and immigration for the ‘worse’ present (Schumacher and van Kersbergen, 2016; Owen and Johnston, Reference Owen and Johnston2017; Colantone and Stanig, Reference Colantone and Stanig2018; Goerres et al., Reference Goerres, Spies and Kumlin2018). To revert to the ‘better’ past, radical right parties therefore propose limiting and reversing such processes which these parties claim to have contributed to the ‘worse’ present. Among these different processes, radical right parties blame immigration the most (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008).

When radical right parties associate economic vulnerability with immigration, economically vulnerable workers may perceive immigration as a more salient cause of economic and societal upheaval than other sources of economic and social disruption (Rovny, Reference Rovny2013). Put differently, such workers may perceive immigration as more salient and responsible for their economic travails than international trade and automation. These workers may therefore view immigration as a major cause of their economic vulnerability, even if vulnerability would be in fact be primarily attributed to other sources of disruption such as automation and international trade. This line of thought maybe reinforced by the fact that the labor market effects of trade and technological change are comparatively similar to those of immigration (Ottaviano et al., Reference Ottaviano, Peri and Wright2013), but migration is often associated with lower incomes and employment, whereas technological change and trade are usually linked with lower prices and quality improvements (Geraci et al., Reference Geraci, Kaiser and Thewissen2017). Nevertheless, they all disproportionally affect the bottom and middle, male-dominated, blue-collar types of work (Frey and Osborne, Reference Frey and Osborne2017).

The argument and hypotheses

To sum up our theoretical expectations, we argue that labor market risks and prospects associated with occupational characteristics shape peopleʼs views on immigration. From the perspective of labor market risks, the expected implications of technological change are rather evident: routine-biased technological change should increase labor market risks in occupations whose task content is high. Therefore, we expect individuals to become more sceptical about economic consequences of immigration as their occupational task routineness increases.

Hypothesis 1: The routine workers should be more worried about economic effects of immigration than nonroutine workers in spite of the level of offshorability (unconditional effect).

The impact of offshorability on labor market risks and, thus, political preferences is more heterogeneous. Workers in offshorable occupations face more competition from foreign workers than workers in nonoffshorable occupations, but are not necessarily more vulnerable. The degree of vulnerability depends on a workerʼs comparative advantage in the global market. Offshorability provides opportunities to high-skilled workers who perform mostly nonroutine tasks (Rommel and Walter, Reference Walter2017), but increases risks of low-skilled workers who perform mostly routine tasks (Hummels et al., Reference Hummels, Jørgensen, Munch and Xiang2014).

Therefore, we expect higher occupational offshorability to increase scepticism toward the economic benefits of immigration in high-routine occupations, but higher offshorability to also increase optimism toward immigration in low-routine occupations.

Hypothesis 2: In comparison to workers in non-offshorable occupations, the workers in offshorable occupations should be relatively more anti-immigration if their occupational task routineness is high and relatively more pro-immigration if their occupational task routineness is low (conditional effect).

As technological change is considered to shape labor markets more profoundly than offshoring (Goos et al., Reference Goos, Manning and Salomons2009, Reference Goos, Manning and Salomons2014), we expect that the association between task routineness and immigration attitudes to be stronger than the association between occupational offshorability and immigration attitudes.

Data description and empirical strategy

We test our hypotheses using cross-sectional and cross-national data from the European Social Survey (Rounds 1–7). There are three main strengths of the European Social Survey (ESS). Firstly, it maintains a consistent battery of questions measuring respondents’ attitudes toward immigration, which allows the operationalization of our dependent variable. Secondly, these questions are phrased similarly across questionnaires for each country. Thirdly, it classifies respondents according to their occupational categories using the International Standard Classification of Occupation (ISCO) 1988 and 2008 systems across all ESS rounds. The availability of detailed occupational categories at the 4-digit level across ESS rounds allows us to construct the two explanatory variables used in this study – (a) the potential of occupational offshorability and (b) the level of task routineness of occupations. To synchronize the two ISCO classification systems, we used the crosswalk provided by Ganzeboom and Treiman (Reference Ganzeboom and Treiman2010) to downgrade the occupations coded in ISCO-08 to ISCO-88.

To operationalize occupational offshorability, we referred to the index provided by Blinder (Reference Blinder2009) which assigned a value to each of the 817 occupational categories listed in the Standard Occupation Classification (SOC) 2000. As a crosswalk to ISCO 08 only exists for the newer SOC 2010, we first crosswalked SOC 2000 to its newer classification index SOC 2010. Most of the ISCO 08 categories had a one-to-one fit with the SOC 2010 categories. Some ISCO 08 categories were however composed of multiple SOC 2010 categories. To get around this, we use the weighted mean value of potential offshorability of the component SOC 2010 categories. The weights are obtained in proportion to the number of workers in each SOC 2010 category obtained from Labour Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey conducted by the Bureau of Census for the Bureau of Labour Statistics in the USA.Footnote 1

The Blinder index assigns values of potential offshorability on two criteria: (1) does the worker in this occupation need to be physically close to a specific work location and (2) does the worker in this occupation need to be physically close to the work unit? (Blinder, Reference Blinder2009, p. 18). Higher values on the Blinder index indicate a greater potential of offshorability. Blinder however cautioned against treating the scale as cardinal. Instead, he recommended it to be used as a categorical classification system in which values ranging from: (a) 76–100 indicate that an occupation is potentially highly offshorable, (b) 51–75 indicate that an occupation is potentially offshorable, (c) 26–50 indicate that an occupation is potentially non-offshorable, and (d) 0–25 indicate that an occupation is potentially highly non-offshorable. For the purposes of this study, we collapsed the index into two categories similarly to Owen and Johnston (Reference Owen and Johnston2017). Our variable measuring potential offshorability is thus a dummy with 0 indicating that an occupation is potentially non-offshorable and 1 indicating that an occupation is potentially offshorable.

To measure task routineness, we used the routine task intensity index (RTI) from Acemoglu and Autor (Reference Acemoglu and Autor2011). The RTI assigns occupations scores according to the level of routineness in their constituent tasks. It is constructed by subtracting the sum of log of abstract and the log of manual tasks from the log of routine tasks from the O*NET database. Higher values on the RTI indicate higher levels of occupational task routineness. We assigned RTI values to each of the ISCO categories at the 4-digit level using data from Owen and Johnston (Reference Owen and Johnston2017) (see Appendix Table A2). The centered values range from −2.12 (religious professionals) to 2.49 (metal moulders and coremakers).

Our theory suggests that the effect of task routineness and offshorability should be conditional on the countryʼs comparative advantage on supplying these tasks. Thus, the difference between routine and nonroutine workers should be more pronounced the richer the country is. We therefore use the 16 richest countries in the ESS data based on their GDP per capita.Footnote 2 Another reason to focus on the richest countries in the sample is that because they are relatively advanced, they should be similarly affected by overriding transnational forces.

Our main dependent variable is the ESS question ‘Is immigration bad or good for countryʼs economy’, which is a scale from zero to ten. While this variable may reflect all kinds of economic concerns over immigration, it is more likely to be associated with concerns over fiscal burden than labor market competition (Dustmann and Preston, Reference Dustmann and Preston2006).

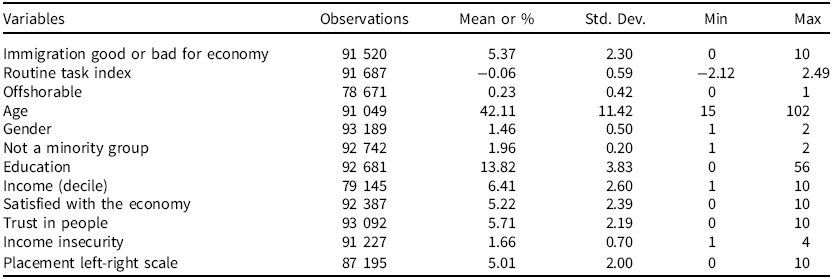

We use ordinary least squares models, include country and year dummies and cluster the standard errors by country. The data are weighted by the design weights and the population size weights. We include standard controls used in the literature of policy preferences in our models. These include age, gender, income,Footnote 3 education,Footnote 4 position on left-right scale, and whether the respondent belongs to a minority group (see Appendix Table A3). We include only the respondents who have been in paid work in the last seven days before the interview, because our proxies of occupational threat are only relevant for those who have a job.

Formally, we estimate the following regression:

Here, Yi,c,t measures the attitudes toward immigration of individual i in country c in the year t, RTIi,c,t is the occupational task routineness, OFFi,c,t is a dummy for offshorability, RTIi,c,t * OFFi,c,t is the interaction term of task routineness and offshorability, and Zi,c,t is a vector of control variables.

Results

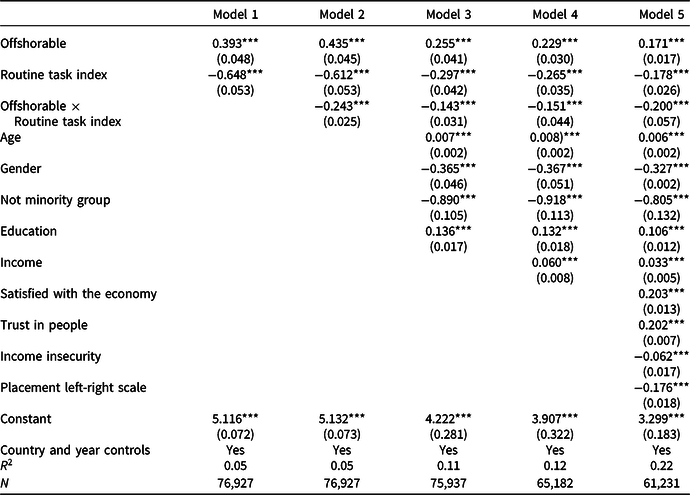

We present our main results in Table 1. All our models include country and year controls (but give similar results without). Model 1 contains only the offshorability dummy and the measure of task routineness. Model 2 adds the interaction term for the two. Models 3 and 4 include individual-level controls suggested in the literature with and without control for income (we expect that income is to a large part a result of occupational characteristics). Model 5 adds further controls for subjective views that might be correlated with attitudes toward immigration.

Table 1. Regression results. Immigration is bad or good for countryʼs economy

Data: European Social Survey rounds 2002–2014. Pooled ordinary least squares (OLS).

* P < 0.1; ** P < 0.05; *** P < 0.01

Our five models show remarkable consistency.Footnote 5 Older people, male, minorities, highly educated, and wealthy seem to have a more positive view on the economic effects of immigration. These findings are generally similar to previous literature.Footnote 6 However, the main interest of this paper lies in the effect of task routineness, offshorability, and their interaction. These occupational characteristics seem to have an opposite impact on immigration attitudes. Offshorability increases positive attitudes toward immigration, whereas task routineness decreases positive attitudes toward immigration.

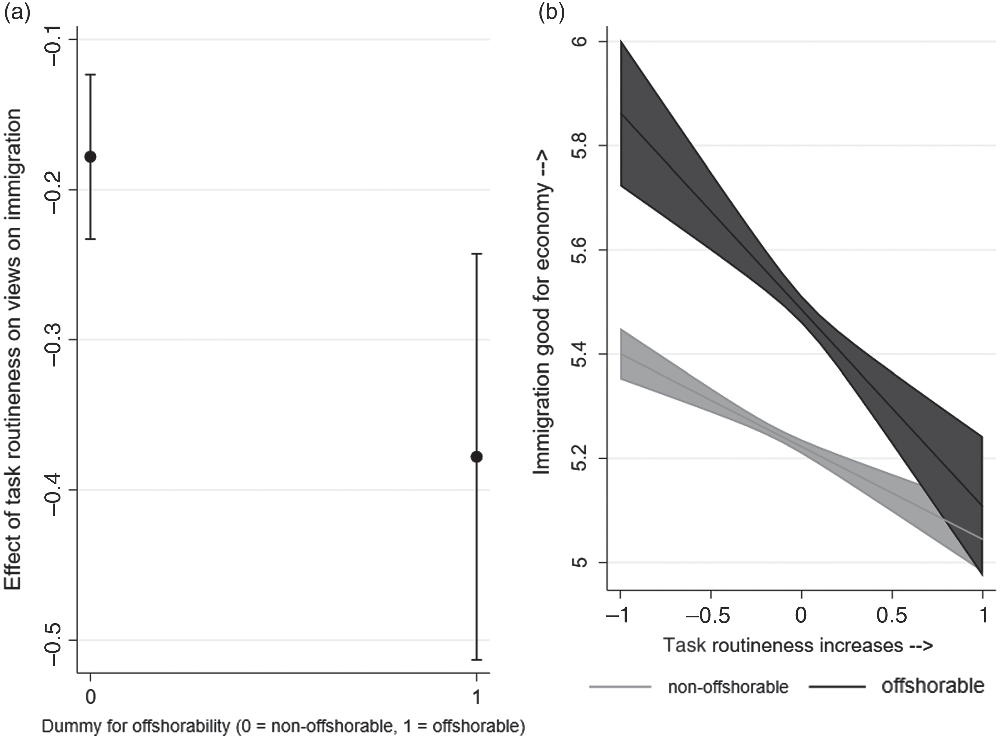

The interactions in Models 2–5 show that the effect of task routineness is conditioned by the degree of occupational offshorability. As offshorability increases, the difference in attitudes between people in routine and nonroutine occupations grows as well. To facilitate interpretation, the conditional effect of offshorability is illustrated in Figure 1a and 1b. The Figures show that the degree of offshorability is associated with the changes in attitudes when task routineness is low, but not so much when the task routineness is high. People in offshorable and low-routine occupations are most supportive of economic immigration, but contrary to our expectations, the people in offshorable routine occupations are not more anti-immigration than their reference group.

Figure 1. Predicted probabilities of task routineness on attitudes toward immigration in non-offshorable and offshorable occupations. 95% confidence intervals. Figures based on the Model 5 in Table 1.

Figure 1a shows how the effect of task routineness varies based on offshorability. One unit change in task routineness leads to −0.18 change in immigration attitudes when the occupation is not offshorable and to −0.38 change when the occupation is offshorable. On the immigration attitude scale, which ranges from 0 to 10 (mean 5.37), the difference between most routine and most nonroutine occupations is 0.80 in non-offshorable occupations and 1.69 in offshorable occupations. This is a substantial difference given the fact that we control for a number of factors that are either determinants (education) or outcomes (income and income insecurity) of occupational characteristics.

Based on Table 1 and Figure 1, we can reject the null hypothesis of our Hypothesis 1 and conclude that people in routine occupations are noticeably more aversive of the economic impact of immigration. The Hypothesis 2, where we expected offshorability to have a conditional effect on the immigration attitudes, is a bit more complicated. While the conditional effect of offshorability seems clear, Figure 1b shows that differences between the most routine workers in offshorable and non-offshorable occupations are statistically insignificant. Thus, we can reject the null hypothesis of Hypothesis 2 only partly. Offshorability increases the pro-immigration attitudes among the workers in low-routine occupations, but there seems to be no statistically significant increase in anti-immigration attitudes associated with offshorability among the high-routine workers.

Our results suggest that task routineness of an occupation is strongly correlated with how people see the economic effects of immigration. They also suggest that the effect of task routineness on immigration attitudes is different, conditional on offshorability, but people in occupations that are more exposed to the global economy are in general more – not less – confident of the positive economic effects of immigration.

However, another side of the story is that international trade might indeed increase polarization in attitudes between occupational groups. The subgroup of people we identified as ‘globalization winners’ has clearly the most positive view of the economic effects of immigration. The differences in attitudes between workers who supply high-routine and low-routine tasks are much lower in the non-offshorable occupations.

Robustness checks

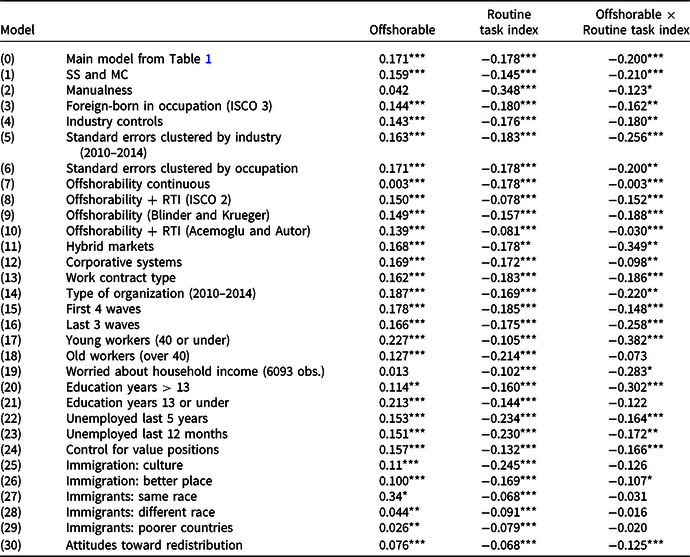

We run a number of sensitivity checks to test our results. We describe the results in Table 2. To save space, we present only the coefficients for offshorability, task routineness, and their interaction. All the models include the same controls as the Model 5 in Table 1 if not stated otherwise.

Table 2. Robustness checks

Data: European Social Survey rounds 2002–2014. Pooled ordinary least squares (OLS).

* P < 0.1; ** P < 0.05; *** P < 0.01

Our key independent variables are proxies of occupational threat to automation and international trade, but they do not capture the direct labor competition from immigrants, which is obviously a potential source of negative immigration attitudes. We try to mitigate this concern by controlling some of the proxies of labor market competition introduced in previous literature. We start by adding controls for skill specialization (SS) and monitoring costs (MC), which Polavieja (Reference Polavieja2016) uses to capture the extent to which workers have to make post-schooling investments in order to do the task required (SS) and proxy to how many incentives the employee has to incentivize workers’ long-term cooperation without incurring costly supervision. Following Ortega and Polavieja (Reference Ortega and Polavieja2012), we transfer the ESS question, ‘If someone with the right education and qualifications replaced you in your job, how long would it take for them to do the job reasonably well’ in months to measure SS. The question to measure MC, ‘How easy/difficult it is for your immediate boss to know how much effort you put into work’ (scale 0–10) is only available in ESS round 5. We take the average scores for each occupation (ISCO four digits) in ESS round 5 and use them in the pooled dataset. Adding these controls does not affect our key coefficients much (Model 1).

In Model 2, we control for the manual intensity of the occupations by using the same scale that was employed to create the routine task intensity. The scale measures the nonroutine manual task content of the occupations (Acemoglu and Autor, Reference Acemoglu and Autor2011) and involves both nonroutine physical and nonroutine personal tasks (Owen and Johnston, Reference Owen and Johnston2017). Note that this is a slightly different measure from Ortega and Polavieja (Reference Ortega and Polavieja2012) and Polavieja (Reference Polavieja2016), who measure manual dexterity intensity and communicational intensity of the occupations. Controlling the manual intensity of the occupations reduces the size of the RTI and offshoring coefficients and leaves the interaction term significant at 90% confidence level. The drop in significance might be simply because the negative correlation between routine and manual task intensity is quite high (−0.53). We do not add control for the scale of abstract tasks as the negative correlation with task routineness is very high (−0.86).

In Model 3, we add another control for labor market competition with immigrants. In this model, we include the percentage of foreign workers in each occupation in each country. The data are far from perfect as it comes from the OECD DIOC database, which is based on censuses from the year 2000 and provides information on ISCO 3-digit level. However, we believe it is reasonable to assume that the changes in the type of employment of the foreign workforce have not changed radically enough to change the direction of the effect. All the coefficients of the variables of interest stay highly significant after including the control in the model.

In Model 4, we add controls for the worker's industry using The Statistical Classification of Economic Activities in the European Community (NACE, two-digit numerical codes). Adding industry controls hardly effects the coefficients, which suggests that occupational characteristics are to a large degree independent from the sector of employment. Unfortunately, the NACE classification changes twice during our time period, which means we have slightly different industry controls for different waves. However, limiting our scope only to the last three waves (2010, 2012, 2014), which use the same NACE classification, confirms that our results are not dependent on industrial-level factors. In Models 5 and 6, we account for the fact that standard errors could be correlated on industry or occupation level instead of country level. In both specifications, the results stay rather unchanged.

Next, we use different measures of offshorability and task routineness. Model 7 employs the (Blinder, Reference Blinder2009) offshorability scale as a continuous variable and Model 8 takes both scales from (Goos et al., Reference Goos, Manning and Salomons2014), which uses ISCO 2-digit classification. In Model 9, we apply the Blinder and Krueger (Reference Blinder and Krueger2013) offshorability index, which is based on professional coders’ expertise on task offshorability.Footnote 7 In Model 10, we take the measurements of task routineness and offshorability from Acemoglu and Autor (Reference Acemoglu and Autor2011). These indices go well together as they are designed to be orthogonal to each other. Because of different scaling, the size of the effect in most regressions is not comparable to our original model, but most importantly, all models are statistically significant and the direction stays the same.

In Models 11 and 12, we control for institutional differences between countries. The Varieties of Capitalism framework (e.g., Estevez-Abe et al., Reference Estevez-Abe, Iversen, Soskice, Soskice and Hall2001; Hall and Soskice, Reference Hall and Soskice2001; Busemeyer, Reference Busemeyer2014) posits that there is a significant variation in occupational structures of European countries based on the type of institutional framework – liberal or coordinated market economies. In the former, workers tend to have more general skills and in the latter more specialized skills, which might affect how vulnerable they actually are to automation and offshoring. To test this, we split our sample to subsamples of liberal and hybrid market economies (Ireland, Italy, Spain, UK) and more coordinated market economies (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland). We find that the size of the interaction term is much larger in the liberal and hybrid market economies (Model 11) than in the coordinated market economies (Model 12). This finding supports our argument on economic vulnerability as the workers in liberal and hybrid market economies are arguably more exposed to trade and automation.

Models 13–24 add new controls from ESS and use different specifications. Adding controls for work contract type (Model 13), which can be used as a proxy for labor market outsiderness (Thewissen and Rueda, Reference Thewissen and Rueda2019) and the type of organization one works for (Model 14) do not make a difference. Dividing the sample into two periods – roughly pre and post-financial crisis – (Models 15 and 16) reveals that our results are rather constant over time. Running the regressions separately for young and old workers (Models 17 and 18) shows that occupational characteristics seem to be associated with immigration attitudes especially among the former. This might be due to a number of factors. Firstly, the difference between routine and nonroutine workers might be more pronounced among the generations that are in general more international and more prone to adapt new technologies. Secondly, as Kitschelt and Rehm (Reference Kitschelt and Rehm2014) argue, occupations shape individuals’ preferences. Old workers are more likely to be affected by this occupational socialization process, whereas younger workers are not.

When we restrict our sample to those workers who find it difficult or very difficult to live comfortably on current income (Model 19), we find that the size of the interaction term coefficient increases, but the statistical significance suffers (most likely) from a lower number of observations. In Models 20 and 21, we split the sample into two reasonably equally sized subsamples based on the years in education. The first subsample comprises individuals with more than 13 years of education and the second individuals with 13 years or less of education. RTI is highly statistically significant for both groups, but the interaction term only for the highly educated (P = 0.102 in the subsample of the lowly educated). The result reflects most likely two things. Firstly, the number of ‘globalization winners’ is too low in the subsample of the lowly educated to reveal real difference in comparative advantage. Secondly, the lowly-educated in non-offshorable occupations are more likely to face direct labor market competition from immigrants (Dancygier and Walter, Reference Dancygier, Walter, Pablo Beramendi, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015), which might conceal the effect of international trade.

Next we control whether the respondent has been unemployed for the last 5 years (Model 22) or 12 months (Model 23) before the interview. Having experienced unemployment does not affect the results much. Unfortunately, we cannot restrict the sample to include only the individuals who faced unemployment, because the sample size would drop dramatically.

In Model 24, we add a number of controls for other issue opinions than immigration. Adding controls for trust in politicians (trstplt), political parties (trstprt), parliament (trtsprl), European parliament (trstep), satisfaction with government (stfgov) and democracy (stfdem), opinions on European unification (euftf), and gay and lesbian rights (freehms) separately or all together (as in Model 24) does not change the results much statistically or economically. Interestingly, these survey items work poorly when used as dependent variables, which suggests that the association between economic vulnerability and immigration attitudes is a separate issue from general unhappiness with how the society is run.

Finally, we test our model using slightly different dependent variables associated with immigration attitudes and attitudes toward redistribution. In Models 25–29, we use the following questions on the left-hand side of the regression: ‘countryʼs cultural life undermined or enriched by immigrants’ (25), ‘immigrants make country worse or better place to live’ (26), ‘country should allow many/few immigrants from the same race/ethnic group as majority’ (27), ‘country should allow many/few immigrants of different race/ethnic group from majority’ (28), ‘country should allow many/few immigrants from lesser developed economies outside Europe’ (29).Footnote 8 The coefficients on offshorability and task routineness differ little from our main model, which is what we would expect, given the fact that people who dislike one aspect of immigrants/immigration tend to be aversive of other aspects too. The interaction term is only statistically significant at the 90% confidence level in one of the models (26). While we should not put too much emphasis on models that have little statistical significance, the fact that the interaction term has no correlation with questions that measure racial or ethnical prejudice or cultural anxiety, gives support to the argument that our model really proxies economic anxiety.

This argument gets further support from Model 30 where we use the question ‘government should reduce differences in income levels’ as the dependent variable with higher coefficients indicating less support and lower coefficients indicating more support for redistribution. People in offshorable occupations are less in favor of redistribution, whereas people in routine occupations demand more redistribution. The interaction term shows that the differences based on routine task intensity become more pronounced in offshorable occupations.

Taken together, the sensitivity checks imply that the coefficients on offshorability and task routineness are remarkably robust to different specifications. While the interaction term does not survive all of the robustness tests, it lacks statistical significance only in a few models. We have no reason to assume that these models are enough to obliterate the countering evidence from the other specifications.

Conclusions

In this paper, we have studied how occupational characteristics are associated with immigration attitudes in 16 Western European countries. More specifically, we have examined whether the labor market vulnerabilities and prospects – measured in terms of occupational task routineness and offshorability – increase probability of having anti-immigration attitudes. To our knowledge, this is the first paper to examine the association between task routineness, offshorability, and immigration attitudes in Europe. We find that workers in occupations that are most vulnerable to automation have the most negative view on immigration. Furthermore, and similarly to papers studying trade preferences (Owen and Johnston, Reference Owen and Johnston2017) and demand for social protection (Walter, Reference Walter2017), our study suggests that the exposure to globalization has conditional effect on immigration attitudes.

The association between offshorability and immigration attitudes seems to be conditional on the routine task content of oneʼs occupation. People in occupations that are both nonroutine and offshorable are substantially more welcoming toward immigration than the working age population generally. As the task content of oneʼs occupation increases, the differences between people in offshorable and non-offshorable occupations start to shrink leading to a state where the differences are no longer statistically significant.

The fact that people in offshorable occupations are generally more welcoming toward immigration signals that the fragmentation of the production chains and the so-called ‘trade in tasks’ does not lead to more anti-immigrant attitudes. This is generally in line with the long-term development of immigration attitudes in Europe. In spite of the intensification of international trade, offshoring and fragmented production chains, the attitudes toward immigrants have become more positive over time on aggregate level. On the other hand, our results suggest that differences in immigration attitudes between routine and nonroutine workers become more polarized as offshorability increases. We argue that this polarization reflects the distributional consequences of international trade at the occupational level. In advanced economies, trade increases relative demand for nonroutine tasks and decreases relative demand for routine tasks improving the labor market prospects of workers whose jobs involve mainly nonroutine tasks, but increasing labor market vulnerability of workers whose jobs involve mainly routine tasks.

Our results suggest that labor market risks and opportunities are associated with immigration attitudes even if they stem from completely different sources than direct labor market competition with immigrants. The labor market risks caused by automation, international trade, and immigration are disproportionally large for routine workers in blue-collar occupations. Even if these workers would act out of self-interest to mitigate their labor market risks, they may be prone to misattribution because of the similarity of the threats they are facing. Blaming immigration is arguably easier than blaming technological change and international trade, which are generally acknowledged as key sources of economic growth. Moreover, blaming immigration is likely fuelled by the rhetoric of radical right parties, which increasingly attempt to tie economic issues to immigration issues thus increasing the salience of the economic threat from immigration.

Our study has two important limitations. First, it is likely that people in offshorable occupations have more direct contact with immigrants than their reference group. Contact theory predicts that positive contact with immigrants lessens misconceptions, improves empathy, and reduces intergroup anxiety (e.g., Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Paolini, Pedersen, Hornsey, Radke, Harwood and Sibley2012). On the other hand, group threat theory expects contact with immigrants to increase the sense of threat among the nonimmigrants, who then become sceptical toward immigration (e.g., Ceobanu and Escandell, Reference Ceobanu and Escandell2010). As both theories are hard to test methodologically with our data, we just have to accept this possible constraint.

Another limitation of our study is that we cannot completely overrule labor market competition as the true cause of the association between occupational characteristics and immigration attitudes. For example, it is possible that the reason why our models shows no statistically significant difference in immigration attitudes between the workers in occupations that involve predominantly offshorable routine tasks and workers in occupations that involve predominantly non-offshorable routine tasks is because the former are more vulnerable to international trade and the latter to competition from immigrants (see Dancygier and Walter, Reference Dancygier, Walter, Pablo Beramendi, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015). We try to tackle these concerns by running a large set of robustness tests and using some of the same controls that studies focusing on direct labor market competition (Ortega and Polavieja, Reference Ortega and Polavieja2012; Polavieja, Reference Polavieja2016) have used.

However, our approach complements these existing studies on labor market competition (e.g., Ortega and Polavieja, Reference Ortega and Polavieja2012; Billiet et al., Reference Billiet, Meuleman and De Witte2014; Polavieja, Reference Polavieja2016) by stressing new sources of economic vulnerability. Our findings imply that focusing on the direct labor market threat from immigration may underestimate the overall importance of economic factors in explaining the immigration attitudes. This line of reasoning echoes with the studies that emphasize status anxiety as a source of support for the populist right (Gidron and Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2017).

Our results indicate that international trade might increase differences in policy preferences between ‘the winners and losers’. From this point of view, our study supports the hypothesis that occupational differentiation may explain the micro-logic of political polarization (Kitschelt and Rehm, Reference Kitschelt and Rehm2014). This kind of polarization might increase political tensions and segmentation within countries even if the majority of the population benefits from economic integration. The most likely beneficiaries are radical right parties, who are the issue owners of sociocultural issues like immigration (Rooduijn and Burgoon, Reference Rooduijn and Burgoon2018, p. 1747) and whose support base consists of disproportionally big amount of workers in routine occupations.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the funding provided by the Strategic Research Council of the Academy of Finland (grant no. 312710). Previous versions of this paper were presented at the Annual Conference of the Finnish Political Science Association (Tampere, 12–13 March 2018) and at the Annual Conference of the International Political Economy Society (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2–3 November 2018). We are grateful for the comments from these sessions. We are also grateful for the helpful comments from three anonymous reviewers. Finally, we would like to thank Stefan Thewissen and David Rueda for generously sharing their codes.

Appendix

Table A1. Correlation matrix: key variables linked to labor market vulnerability

Table A2. Top ten and bottom ten occupations ranked based on the routine task intensity index and offshorability index

Table A3. Descriptive statistics for key variables