Interprofessional education (IPE) was originally defined by the Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education (1997) and clearly articulated in 2002 (Reference BarrBarr 2002). There has been international agreement that it ‘occurs when two or more professions learn about, from and with each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes’ (World Health Organization 2010: p. 13). This definition implies that students from different professions must come together in the learning process to achieve their intended learning outcomes. In this way, students bring their uniprofessional specific knowledge and skills into interprofessional learning to mirror the complexity of team-based clinical practice.

Interprofessional education has existed in the formal preregistration curriculum for about 10 years, and was affirmed as essential by the General Medical Council in Tomorrow’s Doctors (General Medical Council 2009). This directive is similarly reflected in curricula for nursing and all allied health professions (Nursing and Midwifery Council 2008; Health & Care Professions Council 2012). As a result, students are emerging from preregistration courses primed to learn in this way (Reference BarrBarr 2007). Indeed, the Foundation Programme Curriculum expects ongoing training to include preparation for team working (section 1.4, Foundation Curriculum; UK Foundation Programme 2012) and competencies to interface with different specialties and professionals (section 7.9). It is implicit in the psychiatry core training curriculum (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2010) that good interprofessional collaboration is key for those who choose to train in psychiatry. In addition, all doctors in the UK are now required to produce evidence for revalidation, for which one of the domains is communication, partnership and team work (General Medical Council 2012).

This article will explore the paucity of interprofessional education in current postgraduate programmes for doctors and other practitioners preparing to work in mental health teams. We will offer solutions based on our extensive experience which are framed in sound theoretical principles for team-based learning and involve patients as a central component.

Team working in mental health services

Team working and collaborative practice have always been a key component of patient care in mental health services. This is because patients present with complex mental health needs and interrelated social problems that often require a response from medicine, nursing, psychology, occupational therapy and social work. Traditionally, the doctor has taken a leadership role relating to diagnosis, whereas treatment plans and long-term care – areas in which concepts such as recovery, support and therapy are important – have been shared across medicine, nursing, occupational health and psychology. In addition, the social worker places the patient (client) in their social and cultural context. On the whole, these teams have learnt ‘on the job’ how to work with each other. Community mental health teams (CMHTs) are seen as providing joined-up multi-professional services for individuals with complex care needs (Reference GlasbyGlasby 2004a), and in the UK, the care programme approach (CPA) was designed to support team working (Department of Health 1990) and collaborative practice (Box 1). However, despite efforts within organisations to improve team working there continue to be errors, concerns and national inquiries that highlight poor team working within mental health services (Reference Ritchie, Dick and LinghamRitchie 1994; Reference Prins, Stanley and ManthorpePrins 2004).

BOX 1 The care programme approach (CPA)

The key components of the CPA are:

-

• an interagency assessment of the individual’s health and social care needs

-

• an assessment of risk factors for the individual or others

-

• a CPA care plan to address the assessed needs

-

• the identification of a care coordinator

-

• regular reviews

-

• the identification of gaps in service

The day-to-day practicalities of team working in mental health services remain difficult, and conflicts and challenges arise when professions have different value bases and report to different statutory accountable structures. The concept of values within health and social care includes anything that is ‘valued’, and might embrace ethics, justice, principles, morals and individuals’ personal beliefs. A particular problem, for example, is the sharing of information (Reference Richardson and AsthanaRichardson 2006). A number of obstacles to good collaborative practice have been identified. These include structural, procedural, financial, professional and status-based factors, not least of which is who takes the lead and has the power (Reference Peck and DickinsonPeck 2008).

A review of partnership working across different teams and organisations in mental healthcare delivery (Reference Glasby and LesterGlasby 2004b) identified several barriers to good team working and possible solutions. The barriers included:

-

• professional self-interest, including aspects of autonomy and accountability

-

• financial resources and constraints

-

• procedural differences between teams.

No easy solutions to these difficulties were found.

There has been an ongoing call for more training to prepare practitioners to work effectively in teams (Reference Whittington, Weinstein, Whittington and LeibaWhittington 2003; Reference HopeHope 2004). Box 2 summarises the Audit Commission’s (1998) explanation of how effective partnerships might help organisations. Box 3 lists the ‘essential shared capabilities’ in which all National Health Service (NHS) mental healthcare staff should be trained (Reference HopeHope 2004).

BOX 2 Effective partnerships

Effective partnerships can help agencies to:

-

• deliver coordinated packages of services to individuals

-

• tackle so-called ‘wicked issues’ (complex problems that cross traditional agency boundaries)

-

• reduce the impact of organisational fragmentation and minimise the effect of any perverse incentives that result from it

-

• align services provided by all partners with the needs of patients

-

• make better use of resources

-

• stimulate more creative approaches to problems

BOX 3 The 10 essential shared capabilities for all NHS staff

-

1 Working in partnership – with patients, carers, families, colleagues, etc.

-

2 Respecting diversity

-

3 Practising ethically

-

4 Challenging inequality

-

5 Promoting recovery

-

6 Identifying people’s needs and strengths

-

7 Providing patient-centred care

-

8 Making a difference

-

9 Promoting safety and positive risk-taking

-

10 Personal development and learning

Team roles of psychiatrists

There has been a plethora of documents looking at how psychiatrists should work in teams (Department of Health 2005). Psychiatrists’ roles are changing to provide expertise in assessment and treatment and operate on a consultative model. Other team members (e.g. nurse prescribers) are taking on some of the roles more commonly (Reference HopeHope 2004) associated with doctors, and doctors within the team are asked to see only the patients with the complex problems. Responsibility for care, which once sat firmly with the psychiatrist, is now shared between team members. Care depends on collaborative work, with each team member sharing their unique skills and abilities.

Current provision

Interprofessional education has been endorsed for preregistration courses as it prepares undergraduate students for collaborative working (Reference Barr and LowBarr 2012). There are examples of programmes for mental healthcare, although contact is often limited and not all professions are included (Reference CarpenterCarpenter 1995; Reference Curran, Sharpe and ForristallCurran 2008). Looking at the educational continuum, there are also some examples of interprofessional education for postgraduate mental health teams, but these initiatives are rare, mostly because of the complexity of aligning postgraduate courses (Reference Barnes, Carpenter and BaileyBarnes 2000; Reference Reeves and FreethReeves 2006). There is evidence that attendance at postgraduate courses organised as part of CPD is higher among nursing staff than among psychiatrists and psychologists (Reference McCann, Higgins and MaguireMcCann 2012). There is huge scope for developing more relevant interprofessional education relating to the complexity of mental healthcare for all professionals. In medicine, the need to provide evidence for revalidation might encourage the provision of postgraduate interprofessional education.

Solutions: the way forward

Interprofessional education may offer solutions for shaping professional behaviour and for developing effective teams. It focuses on theories of learning centred not on the individual but on learning with others in sociocultural clinical contexts. Its premise lies in adult learning theory, where the process of learning, i.e. through experience or reflection, is key (Reference KnowlesKnowles 1978; Reference KolbKolb 1984; Reference WengerWenger 1998). Interprofessional education at its best can set up a complex and challenging social learning environment that mirrors the realities of clinical practice and teaches effective team working (Reference BleakleyBleakley 2006). There are obviously socially constructed and mediated power differentials in these mixed student interactions and managing these must be considered (Reference Hean, O'Halloran and CraddockHean 2013).

Undergraduate models of interprofessional education

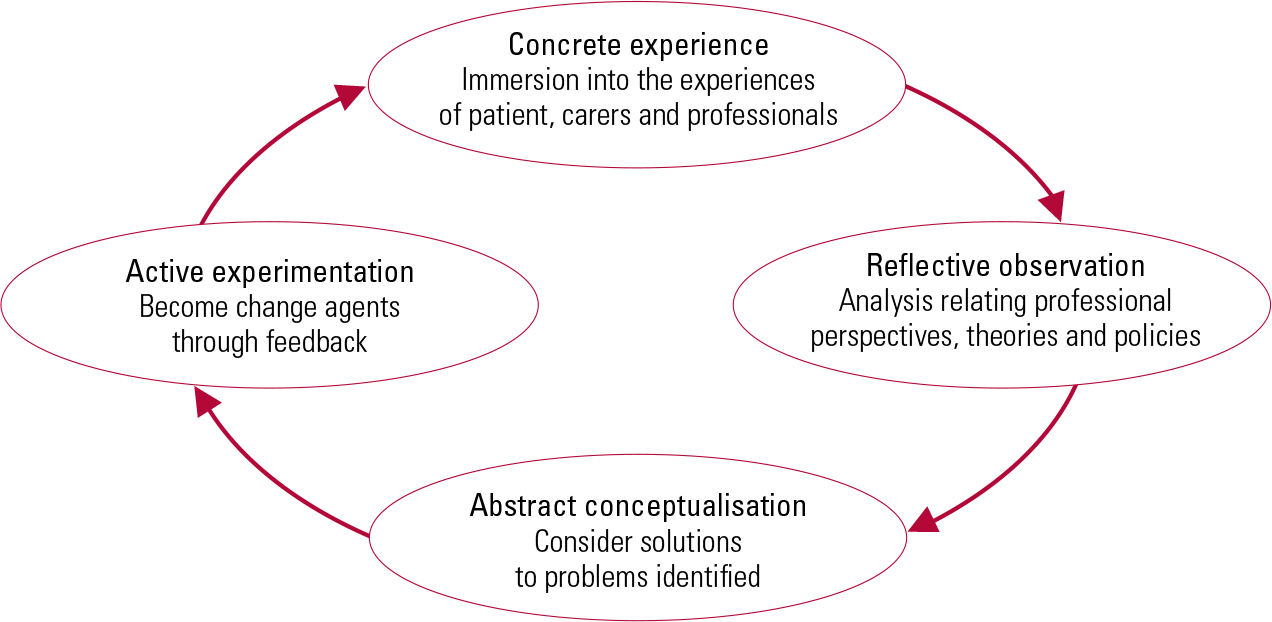

In its original version, the Leicester Model of Interprofessional Education was designed and developed with undergraduate students to enable them to appreciate the complexities of health and social care delivery in meeting the needs of disadvantaged inner-city communities (Reference Lennox and PetersenLennox 1998, Reference Lennox and Anderson2007). The model combines practical understanding of team working and collaborative practice using a patient-centred approach (Reference Anderson and LennoxAnderson 2009). It uses a learning cycle based on the work of Kolb (Fig. 1).

FIG 1 The learning cycle of the Leicester Model of Interprofessional Education (adapted from Reference KolbKolb 1984).

From the student’s perspective learning takes place (cyclically) following four consecutive steps.

1 Concrete experience

Experiential learning in which students work with and learn from patients, carers and professionals in day-to-day clinical practice. The students are immersed in the complexity of team working, and patient/carer perceptions of care are central to and drive the learning.

2 Reflective observation

Students are helped in tutorials to apply theory and policy to their experiences and thus to gain a richer and deeper understanding of patients’ and professionals’ perspectives of care delivery. In this way, students come to understand professional roles and responsibilities.

3 Abstract conceptualisation

Students faced with the complexity of care are helped to reanalyse clinical problems and consider new ways to address and manage care. These new solutions are student generated and can often raise issues not yet considered by the professionals, mostly because students have more time to reflect on what they see.

4 Active experimentation

In the final stage, students feed back to the professional teams changes to practice that they think might improve patient outcomes and that might be introduced into day-to-day procedures.

Shadowing the professionals

The Leicester model places patients at the heart of the experience for undergraduate interprofessional groups, and this mirrors team working with patients in practice (Department of Health 2008). The model has been evaluated from the perspective of students, professionals and patients (Reference Anderson and LennoxAnderson 2009). The learning template has been adopted in different team-based clinical settings, including mental healthcare (Reference Kinnair, Anderson and ThorpeKinnair 2012). The essence of the model is that students are given clinical responsibilities, becoming shadow teams accountable to the professional team. They analyse and explore the existing professional care plans for patients, and throughout are directly involved in the realities of day-to-day practice. In the mental health adaptation, the students mirror the work of a CMHT and feed back on interagency care plans. In this and other adaptations, student teams have identified unmet needs and unsafe practice (Reference Anderson and ThorpeAnderson 2010; Reference Lennox and AndersonLennox 2012).

Involving patients in interprofessional education

The involvement of patients has the benefit of putting the teaching in a real-life clinical context. The Department of Health and the Health and Care Professions Council (until 2012, the General Social Care Council) require the involvement of members of the public in education (Department of Health 2003; General Social Care Council 2003), and, as already mentioned, the Leicester Model of Interprofessional Education places patients at the centre of the cycle of experiential learning. Reference Towle, Bainbridge and GodolphinTowle et al (2009) propose six levels of patient involvement, from case studies through to policy development. The level of engagement may be crucial to the patients’ experience or perspective of the value they place on participating in interprofessional education.

A number of studies have shown the successful inclusion of patients in undergraduate interprofessional education (Reference Cooper and Spencer-DaweCooper 2006; Reference Anderson, Ford and ThorpeAnderson 2011). Patients involved in the mental health interprofessional education course in Leicester reported that they could see the purpose and benefit of bringing students from different professional groups together to learn (Reference Kinnair, Anderson and ThorpeKinnair 2012). They recognised that they received care provided by teams and that joined-up care between teams is sometimes difficult. Although patients were initially nervous about participating in the course, the overwhelming feedback was that they enjoyed taking part and felt that their contribution to education was valued. There is also evidence that postgraduate interprofessional education courses can have a positive effect on patient care (Reference Zwarenstein, Reeves and PerrierZwarenstein 2005).

Interprofessional education in postgraduate mental healthcare

Effective interprofessional collaboration has been seen by policy makers as a key mechanism for tackling poor-quality service delivery, improving patient safety and minimising waste of resources, including clinical time (Department of Health 2001). However, despite repeated suggestions in national policy documents and statements that an interprofessional education approach be taken in mental healthcare, there is little evidence to demonstrate benefits in postgraduate training, and no national strategy.

There is published evidence to demonstrate the benefits of interprofessional education at the postgraduate level in a pilot project involving CMHTs (Reference Reeves and FreethReeves 2006). Interprofessional education was offered to two CMHTs, with the aim of improving collaborative working by providing an opportunity for team members to reflect on collaborative practice and the contribution to care made by each profession within the teams. The teams met for three 2-h workshops. The study reported that the workshops did help to clarify roles and were seen by participants as a valuable space to reflect on different professional perspectives.

The idea of different professional perspectives is an important one in health and social care, and particularly in mental healthcare, where successful recovery requires a biopsychosocial approach. Patients with mental health problems may also experience health inequalities dependent on income, housing, environment, powerlessness to effect change and wider notions of unfairness (Reference Duggan, Cooper and FosterDuggan 2002). A collaborative approach between different professionals and agencies is needed to tackle these complicated difficulties.

From silo to interprofessional education

There is an opportunity to improve the quality of mandatory training programmes within NHS trusts. Many of these courses are multi-professional, but not truly interprofessional. Courses in areas such as risk assessment, child protection, working with vulnerable adults and resuscitation skills require good collaborative care in clinical practice, and could benefit from an interprofessional education approach. Within postgraduate medical education, most core and higher trainees are taught in uniprofessional silos, separately from other branches of medicine for the majority of the time. There is an opportunity to develop interprofessional educational events to cross some of the existing barriers. All psychiatrists will work with a wide variety of professional groups, including general practitioners, physicians and others, and there should be formal learning events to support the development of high-quality multi-agency work.

Taking forward interprofessional education at postgraduate level

Planning and implementing interprofessional education necessitates the involvement of faculties from different health and social care schools, within or across universities. This first step of bringing staff together from different services and backgrounds is often difficult and requires a collegiate approach. If patients are to be involved, it will also be necessary to include clinical, practice-based staff to identify, recruit and support them.

If interprofessional education events are to be successful, they should have several important characteristics. They need the shared enthusiasm of the different disciplines involved in the project, not only in the developmental phase, but to sustain and embed it in several different curricula (Reference ReevesReeves 2008). Staff must model good interprofessional practice and communication in their collaboration and facilitation of learning events. And events must stay abreast of changes in policy at a national level and service changes at a local level that can affect staff and collaborative efforts.

Setting up a postgraduate course

Three key steps need to be considered in the development of a postgraduate interprofessional education course. First, train and bring together the course leaders/facilitators so that they can:

-

• learn more about each other and begin to work interprofessionally, each representing their different professional training

-

• understand each other’s curricula and professional body requirements

-

• learn more about the methods of interprofessional education and how to manage group dynamics

-

• establish intended learning outcomes relevant for all the participating professions

-

• engage with frontline practitioners and individuals from the teams that will be attending the course

-

• plan, where possible, for the involvement of patients and work with them in the early planning stages

-

• decide how the learning will influence practice.

Second, design teaching to align with the intended learning outcomes and assessment process:

-

• decide how the learning will take place

-

• draw on theory to underpin the teaching

-

• agree an assessment strategy.

Third, evaluate the outcomes:

-

• use assessments to see whether the students have learnt from the event

-

• evaluate the impact of the learning event on all participants/stakeholders.

There are many questions to be addressed and these can be aligned to consideration of the ‘presage’, ‘process’ and ‘product’ of learning – the 3P model (Reference BiggsBiggs 1993). Table 1 shows the 3P model as adapted for interprofessional education by Reference Freeth and ReevesFreeth & Reeves (2004).

TABLE 1 Using the 3P modela to shape a learning event in interprofessional education

Discussion

There is still a need for interprofessional education to be firmly embedded for all trainee and consultant psychiatrists. We have offered one model, familiar to us at Leicester, which has been evaluated and adapted for use in mental health settings. Patient-centred models need to be further developed, especially where they offer the opportunity to improve practice. An alternative model that is popular in postgraduate education is the Quality Improvement Programme (Health Foundation 2012), although it is important to avoid delivering this in uniprofessional silos.

Psychiatrists should take the lead

Psychiatrists involved in postgraduate training must work collaboratively with educators in other health and social care professions to forward interprofessional education. This would address concerns that medical faculties have been slow to support interprofessional education, in part because of the recognised imbalance of status and power (Reference Hean, MacLeod Clark and AdamsHean 2006; Reference Curran, Sharpe and ForristallCurran 2007; Reference WhiteheadWhitehead 2007).

Caution is needed not only to create a balance of those leading interprofessional education from across the professions, but also to ensure the right balance of students who attend. In their feedback on interprofessional education events, social work students continue to express concerns about the ‘lack of respect’ shown to them by medical students and the dominance of the medical model in assessing patient need (Reference Smith and AndersonSmith 2008). However, although individual research papers have highlighted a perceived lack of medical participation in interprofessional education, the interprofessional education agenda both nationally and internationally has been supported by many prominent clinicians, including the late Dr John Horder, who founded the Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education (CAIPE) and was a past President of the Royal College of General Practitioners.

Trusting the evidence base

There are several examples in the literature of the benefits of interprofessional education at both undergraduate and postgraduate level. These include learning events on breaking bad news (Reference Wakefield, Cocksedge and BoggisWakefield 2006), community healthcare (Reference Anderson, Lennox and PetersenAnderson 2003) and team working and communication (Reference Parsell, Spalding and BlighParsell 1998). The advantages of interprofessional education have included clarification of uniprofessional roles and responsibilities, and identifying where roles are similar and overlap. Interprofessional education allows students to experience clinically realistic team working situations, and allows potential conflicts to be identified and discussed. Few health and social care practitioners practise in isolation, and interprofessional education is a vehicle that allows students to experience collaborative working at an undergraduate or postgraduate level. There is longitudinal evidence that interprofessional education programmes at the undergraduate level produce attitudinal and behavioural changes that remain after graduation (Reference Pollard and MiersPollard 2008). Students trained in programmes that included interprofessional education were more confident in their interprofessional relationships and communication skills. If mental health services are to become more efficient and effective, interprofessional working and communication will be key to individual professional groups working together.

Interprofessional education is becoming increasingly common in health and social care undergraduate curricula (Reference Hammick, Freeth and KoppelHammick 2007). The evidence for interprofessional education for undergraduates is also growing and it is important that we develop relevant and interesting educational tools to teach different groups of postgraduates the skills necessary for team work and collaboration.

Summary

There is a clear drive to implement and embed interprofessional education in undergraduate curricula to help reinforce students’ preparation for interprofessional team working after graduation (Reference Barr, Freeth and HammickBarr 2006). This focus has also shown that students can become agents of change, not only for individual patients but also, potentially, for future practice within the NHS and social care systems.

Postgraduate education is in danger of being left behind, but interprofessional education at this level may be an opportunity to train and develop staff to implement the huge changes occurring in most NHS-based mental health teams and services. It may also give staff groups the space to reflect on changes to services and their own and their colleagues’ roles in these changes.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Interprofessional education has been defined as:

-

a bringing different professionals together to learn

-

b bringing two or more professionals together to learn about each other

-

c bringing teams together to develop a service

-

d bringing staff from health and social care together to learn about each other’s roles

-

e bringing two or more professionals together to learn from and about each other to improve collaboration and quality of care.

-

-

2 Patients should be involved:

-

a at the planning and course development phase

-

b in facilitating the course

-

c in the course to share their experiences and reflections of care

-

d in both a and c above

-

e in a, b and c above.

-

-

3 Interprofessional education is best delivered:

-

a in clinical settings

-

b in classrooms

-

c at universities

-

d at a location to mirror the course aims and intended learning outcomes

-

e in whatever rooms are available within the hospital.

-

-

4 Barriers to developing interprofessional education can include:

-

a time commitments of staff

-

b bringing together teaching and clinical staff from different professional groups and organisations

-

c the funding needed for patient involvement and facilitators

-

d negative views of teaching staff and students

-

e all of the above.

-

-

5 Interprofessional education courses require:

-

a keen and motivated teaching staff from one profession

-

b keen and motivated staff from several professions

-

c staff who have had training in interprofessional education facilitation

-

d both a and c

-

e both b and c.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | e | 2 | e | 3 | d | 4 | e | 5 | e |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.