Introduction

European Freedom of Movement (EFM) – consisting of free movement of persons, residency and equal treatment – was a central issue in the June 2016 referendum on the UK's membership of the EU, which resulted in a ‘leave’ vote. The UK government's subsequent decision to pursue a ‘hard Brexit’, entailing withdrawal from the single market, means that it intends EFM between the UK and the EU to cease upon separation from the Union in April 2019 (PMO, 2017), although there may be a transitional period in which it continues (Guardian, 4/04/2017). Agreeing the rights of EU citizens in the UK – almost three million persons, representing 4.6 per cent of the UK's resident population (Eurostat, 2016a) – and those of UK citizens living in other EU member states – an estimated 1.22 million (HoC Library, 2016) – is a stated priority for the Brexit negotiations of the UK government (PMO, 2017) and of the European Commission (EC, 2017). The position of future EU migrants in a UK post-Brexit migration system also remains to be decided.

Although ranking in only sixth highest place among the EU28 in terms of the size of its EU migrant population (Eurostat, 2016b), in recent years – linked to the 2004 and 2007 enlargements and, to a lesser extent, to the prolonged economic crisis in parts of Southern Europe since 2008 – the number of EU migrants arriving in the UK had increased considerably, and the rate of their annual inflow had become higher than that for migrants from outside the EU (respectively 265,000 and 257,000 at year end September 2016) (ONS, 2017). This scenario of rising, and reportedly ‘uncontrollable’ because of EFM, EU migration, became particularly problematic in political terms in the context of David Cameron's 2010 pledge to reduce net migration to the ‘tens of thousands’ per annum by the May 2015 General Election. He failed to meet this target: net migration increased from 244,000 in the year ending June 2010 to 336,000 in the year ending June 2015 (ONS, 2016).Footnote 1 The emphasis in a utilitarian migration policy of selecting ‘the brightest and the best’ (May, Reference May2017) further problematised ‘uncontrollable’ EU migration; this is despite evidence that EU-born migrants living in the UK are better educated than UK-born adults, and as well educated as their non-EU born counterparts (Frattini, Reference Frattini2017).

The contestation of EFM, however, has gone beyond the questions about ‘how many’ and ‘of whom’. In the context of the neoliberal governance of migration in which migrants are confronted with a ‘radical commodification [. . .] as pure labour power’ (Oliveri, Reference Oliveri2012: 796), EFM has stood apart because it does not reduce migrants to individual economic units of labour (Kilkey et al., Reference Kilkey, Plomien and Perrons2014: 180–81): albeit subject to (increasing) limitations and conditions, mobile EU citizens have been able to be accompanied by their family members and, once resident in the UK, EU migrants and family members have had the right to equal treatment in employment, remuneration and conditions of work, as well as broader social entitlements. As a result, EFM has offered choices to EU migrants around how their families are formed, reproduced and cared for in the context of their migration projects. Thus, while acknowledging that structural factors such as differences in education and pension systems, long working hours and high childcare costs, as well as asymmetries within the model of EU citizenship itself, can constrain EU migrants’ choices in the UK, research has also highlighted the diversity of family practices facilitated by EFM, relating to family-formation and family-reunification, the care of children and older people, spanning co-territorial and transnational arrangements, and incorporating a wide range of family members (Kilkey et al., Reference Kilkey, Plomien and Perrons2014; McGhee et al., Reference McGhee, Heath and Trevena2013; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Sales, Tilki and Siara2009; White, Reference White2011).

Consideration of what the implications of Brexit will be for the family rights linked to EFM, and for the family practices and relationships that ensue, motivates the current article. This is an important element to include in analysis of how the UK's migration regime, and the experiences of those governed by it, will be transformed in the context of Brexit. Yet, it is one that risks being elided because research largely considers migrants as individual economic actors (Kilkey et al., Reference Kilkey, Plomien and Perrons2014). It is also important because the question of what the curtailment of EFM will mean for family rights has significance for families beyond those who are EU-national families living in the UK. Thus, what Kofman (Reference Kofman2017) terms ‘Brexit families’ also include families composed of a mix of EU and UK nationals, as well as those composed of EU and non-EU nationals.Footnote 2 And they include not only recent arrivals to the UK, but also long-term resident EU migrants who have not claimed permanent residency or UK citizenship. ‘Brexit families’ also extend beyond the UK to include UK nationals living in another member state who may return with EU or non-EU national family members.

In the article I consider the potential consequences of the curtailment of EFM for the family rights and family practices of those so-called ‘Brexit families’. I draw on findings from an examination of the direction of travel of the family rights attached to three groups – economic migrants from outside the EU, EU migrants and UK citizens with non-UK (both overseas and EU) family membersFootnote 3 – since 2010 and the launch of the ‘tens of thousands’ target. Understanding family rights as constituted at the intersection of migration and welfare policies, I adopt a conditionality analytical frame, drawing on the work of Clasen and Clegg (Reference Clasen, Clegg, Clasen and Siegel2007) and Shutes (Reference Shutes2016). Those authors implicitly take the individual as the unit of analysis but, by examining the family rights conferred on individual migrants and citizens, I develop the conditionality frame, incorporating consideration of implications for their family members and wider life choices in terms of ‘family-life’. The next section elaborates the conceptual and analytical frame, and provides details of my policy analysis approach. The following section presents the findings of how conditionalities at the intersection of migration and welfare organise, condition and set limits on the family-life of the three groups, and the patterns of stratification that result. The conclusion addresses the potential implications of Brexit for family rights within the UK's migration regime.

Conditioning family-life at the intersection of migration and welfare policies

Increasing conditionality in access to social benefits is a salient feature of the ongoing transformation of the UK welfare state (Dwyer, Reference Dwyer2004; Edminston, Reference Edminston2017). Used as one of a number of tools to individualise social risk in a market model of citizenship that emphasises self-reliance through paid work, analysis has focused largely on ‘citizen-workers’ (Dwyer and Wright, Reference Dwyer and Wright2014). Drawing on Clasen and Clegg's (Reference Clasen, Clegg, Clasen and Siegel2007) conditionality framework, Shutes (Reference Shutes2016), however, extends the focus of enquiry to include ‘non-citizen workers’, specifically migrant workers from within and outside the EU, examining how an expanding set of work-related conditions in migration and social security policy intersect to govern migrant workers’ rights of entry, residence and entitlement to social benefits. In doing so, Shutes moves social policy analysis beyond a ‘binary of citizens and migrants’ (Shutes, Reference Shutes2016: 702), a development which is arguably central to challenging the ‘divisive welfare state’ – the scenario in which welfare is used to exacerbate social divisions in order to achieve spending cuts without damaging electability (Taylor-Gooby, Reference Taylor-Gooby2016). Shutes’ focus on workers qua individual workers, however, obscures another aspect in which growing conditionality at the intersection of migration and welfare policies unsettles the binary of citizens and migrants – that of family rights (Kilkey, Reference Kilkey, Foster, Brunton, Deeming and Haux2015).

Migration and family-life

While securing family-life is often a motive for migration (Kilkey et al., Reference Kilkey, Plomien and Perrons2014; Kofman and Raghuram, Reference Kofman and Raghuram2015), migrants’ opportunities during processes of migration to form and reshape their families, as well as maintain links with their kin across borders (e.g. through visits) (Baldassar, Reference Baldassar2014), are deeply stratified, with gender, nationality, class, age and occupation among the most significant axes of differentiation (Kofman et al., Reference Kofman, Kraler, Kohli, Schmoll, Kraler, Kohli and Schmoll2011). How families and the familial-based care that is ‘in many ways constitutive of family-life’ (Baldassar, Reference Baldassar, Kilkey and Palenga-Möllenbeck2016: 20) are treated within migration and welfare systems is a key factor underlying such stratification (Kofman et al., Reference Kofman, Kraler, Kohli, Schmoll, Kraler, Kohli and Schmoll2011). Constructed as individual economic units of labour, migrant workers’ family and care responsibilities have been commonly elided within policy in migrant-receiving ‘rich’ countries. ‘Guest-worker style’ migration schemes, based on circulation and assuming the notion of single, temporary workers without family members, are one manifestation of this (Castles, Reference Castles2006). As a result of the attempts of ‘rich’ member states to manage a range of competing concerns regarding migration, contemporary migration regimes are constituted by an array of different labour migration schemes, which allocate differential rights to different categories of migrant workers, resulting in complex hierarchies of statuses with varying attendant rights, entitlements and conditions (Morris, Reference Morris2003; Carmel and Paul, Reference Carmel and Paul2013), including in respect of family rights (Kofman et al., Reference Kofman, Kraler, Kohli, Schmoll, Kraler, Kohli and Schmoll2011). For EU member states, the post-national right of EFM and the differentiations within this right (Bruzelius et al., Reference Bruzelius, Chase and Seeleib-Kaiser2016; Carmel et al., Reference Carmel, Bozena and Papiez2016; O'Brien, Reference O'Brien2016), contribute further categories to such hierarchies.

Less apparent, however, is that nation-state citizens’ family choices are also directly conditioned at the intersection of migration and welfare policies. This is because efforts by ‘rich’ migrant-receiving countries, including the UK, to manage migration extend beyond labour migration to include family-related migration streams, such as marriage migration, family reunification and family visits. The importance of family-related routes within migration-management strategies lies partly in the fact that family-related migration is perceived to undermine migration control and to be in contradiction of selective migration policies, threatening among other things, national resources such as the welfare state (Bonjour and Kraler, Reference Bonjour and Kraler2015). In this vein, ‘rich’ member states have developed policies that allow for a selective approach to admission through the family route and a restrictive approach to the social rights and entitlements of those resident as ‘family dependants’. As potential sponsors of family members from overseas, such policies condition the family-life of nation-state citizens, including those without a migration background who, as a result of bi-national relationships, have family members who are not citizens of the preferred country of residency.

Conditioning family-life: analytical approach and methods

In examining how conditionality organises, conditions and sets limits on family-life, I focus on two aspects. The first is the formation of a ‘family of choice’ in terms of family/household membership and its geographical location; that is, whether co-territorial in the UK or transnational. This requires examination of the rights of migrants in the UK and of UK citizens, pertaining to entry (including for visits), temporary residence and permanent residence or settlementFootnote 4 of their non-UK-citizen family members. The second aspect concerns the distribution of economic risk between the UK State and the individual (family) for forming a ‘family of choice’. This requires consideration of the rules relating to self-sufficiency and access to social welfare, which are attached to rights of entry (including for visits), temporary residence and permanent residence or settlement for non-UK-citizen family members.

My policy analysis is structured around the analytical approach set out by Clasen and Clegg (Reference Clasen, Clegg, Clasen and Siegel2007) to capture different ‘levels’ and ‘levers’ of conditionality that have been implemented in welfare reform to loosen and tighten access to social rights. Their approach was subsequently extended by Shutes (Reference Shutes2016) to include conditionality at the intersection of migration and social security policy for EU and non-EU migrant workers in the UK. Both contributions identify three sets of levels and levers: conditions of category, encompassing the ‘categorical gateways’ (Clasen and Clegg, Reference Clasen, Clegg, Clasen and Siegel2007: 172) for access to rights, with the re-definition of a particular category acting as the lever expanding or restricting access; conditions of circumstance, incorporating the criteria governing eligibility and entitlement to rights, the changing of which is the lever extending or limiting access; and conditions of conduct, regulating ongoing access to rights, with the levering done through the tightening or loosening of behavioural requirements imposed upon recipients.

Developing the above approach beyond the individual, and to capture how conditionality shapes the possibilities for a ‘family of choice’ and distributes the economic risks for forming a ‘family of choice’, I operationalise in concrete policy terms the three sets of levels and levers of conditionality as follows. Conditions of category are examined in dual terms: firstly, as the categories of migrants that have rights to be visited by non-UK-citizen family members, to have those family members enter and reside temporarily in the UK, and to have them reside permanently or settle in the UK; secondly, as the categories of non-UK-citizen family members (of migrants and citizens) who have rights of visiting, entry, temporary residence and permanent residence or settlement. Conditions of circumstance are examined as the eligibility criteria, including those relating to self-sufficiency and access to social welfare, in respect of entry (including for visits), temporary residence and permanent residence or settlement as a non-UK-citizen family member of migrants and UK citizens. Conditions of conduct are examined as the ‘types of behaviour, activity and relationships’ (Shutes, Reference Shutes2016: 697) that conditions of category and circumstance may indirectly require migrants and UK citizens to adhere to in respect of entry (including for visits), temporary residence and permanent residence or settlement in relation to non-UK-citizen family members.

My data are the conditions in regulations for each group as at January 2017, and the key changes in conditionality for each group since 2010. Data are text-based and derived from: publicly available information on the visas and immigration pages of www.gov.uk, including, where available, accompanying detailed guidance notes; an archive of documentary materials collected as part of my on-going research on reform of the UK migration regime; relevant published reports and scholarship. Analysis of those data is informed by the Interpretive Policy Analysis approach, leading us to focus on the meanings policy regulations attach to the social world, and the ordering / categorising / arranging consequences of those meaning ascriptions (Yanow, Reference Yanow2000).

Conditionality in family rights: non-EU migrants, EU migrants and UK citizens

The family rights of non-EU economic migrants are subject to UK immigration law. This group enters under the Points Based System (PBS),Footnote 5 introduced in 2008 as a tool to select the ‘brightest and the best’ according to wealth, income, skills/talents and language proficiency, criteria which have significant stratifying effects in terms of gender, class and other intersecting socio-economic characteristics (Kofman, Reference Kofman2014). The PBS consists of five tiers,Footnote 6 each with different rights and entitlements, and some with annual quotas. Tier 1 incorporates ‘high skill / high value’ categories. Tier 2 is for sponsored ‘skilled’ workers categories. Tier 5 is for ‘temporary’ categories (including a Youth Mobility category limited to certain nationalities). Tier 3, designed for ‘low-skilled’ categories, has been closed since the PBS' inception because it was expected that low-skilled labour shortages would be filled from within the EU (Paul, Reference Paul2013; Reference Paul2015), as has been the case (Frattini, Reference Frattini2017). Breaking the link between arrival and settlement has been part of the strategy to reduce the level of net migration and, in recent years, the maximum permitted length of stay and the right to settlement have been curtailed for PBS migrants. Most significantly, only those categorised as ‘high-value’ (Tier 1) and ‘skilled’ (Tier 2) are eligible for settlement, with the waiting period extended from two to five years. Moreover, since April 2016, settlement for Tier 2 migrants has been restricted, with some exceptions, to those earning at least £35,000 per annum. Visas are available for dependent family members of most categories of PBS migrants, with, as I discuss below, the eligibility criteria and associated conditions varying depending on the sponsoring family member's visa category. Given the gendered nature of the PBS selection criteria (Kofman, Reference Kofman2014), we can expect women to dominate among the adult dependants of PBS migrants, highlighting the need to attend to the gendered implications of conditionality.

So long as the UK remains a member of the EU, EU migrants are not subject to UK migration control; rather, their rights are conditioned by EFM. The scope of EFM currently is significantly fuller than when free movement was first introduced in Article 48 of the Treaty of Rome in 1957.Footnote 7 Its inclusion then was prompted by the concern to promote labour mobility, and it applied to ‘workers’ only and did not extend to their family members. Subsequently, however, citizens of member states actively tested the boundaries of free movement in the European Court of Justice. Struggles over family rights were part of those challenges, and led over time to the incorporation of family members in EFM provisionsFootnote 8 (Ackers, Reference Ackers1998). It is also important to note that EFM has significant dimensions of differentiation and conditionality (Bruzelius et al., Reference Bruzelius, Chase and Seeleib-Kaiser2016; Carmel et al., Reference Carmel, Bozena and Papiez2016; O'Brien, Reference O'Brien2016), such that the economically active still occupy a privileged category. Thus, the right to reside beyond an initial three-month period is granted to ‘qualified persons’, defined as workers, self-employed, jobseekers, or self-sufficient – that is, having sufficient resources so as not to become a burden on the social assistance system of the host member state.Footnote 9 This privileging of labour-market attachment within EFM suggests, as with the PBS, the need to attend to gendered aspects.

For the purposes of this discussion, it is helpful to distinguish between three groups of UK citizens: firstly, those with non-EU family members, whose rights are governed through the family-migration route, which underwent significant reform in 2012 as part of the strategy to reduce net migrationFootnote 10 ; secondly, those with EU family members, and for whom rights are effectively conferred through the EFM rights of their family members; and thirdly, those UK citizens who having lived in another EU member state with non-EU family members return to the UK, and for whom family rights are then governed by EFM. This so-called ‘Surinder Singh route’ is based on the principle that the right to move from one member state to another must include a right to return, otherwise a person would be deterred from moving in the first place. Those exercising their right to return to their home member state are, therefore, doing so under EU law, and so it is EU law and not the domestic rules of their own member state that apply to them and accompanying family members.Footnote 11

Conditions of category

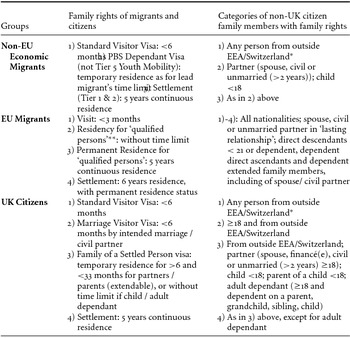

Considering initially conditions of category (Table 1), we see that EU migrants face the least restrictions on forming a family of choice in the UK. All can bring family members to visit for up to three months, and those who ‘qualify’ can bring family members to reside, with no time limit and with a right to settlement. Moreover, the categorisation of ‘family member’ is broad including, among others, non-EU family members and dependent ascendant relatives. Debate preceding the referendum, however, saw the residency rights of non-EU family members of EU citizens subjected to contention. In a government report published in 2014, they were seen as limiting the UK's ability to ‘control immigration from within the EU’, and linked to abuse and fraud in the form of so-called ‘sham marriages’ (HM Government, 2014: 30; 46). Those concerns were articulated in Cameron's pre-referendum negotiations with the EC (Cameron, Reference Cameron2015: 5), and the ‘EU deal’ agreed prior to the referendum committed to changes in EFM, which would have effectively shifted non-EU family members of EU citizens into the category of non-EU migrants subject to immigration controls (European Council, 2016: Annex V11).

Table 1. Conditions of category in family rights, January 2017

Notes: *EEA/Swiss family members have rights as EU migrants under EFM.

** ‘Qualified persons’ are citizens of the EEA/Switzerland and are one of the following: working, studying, self-employed, self-sufficient or looking for work.

Source: Author's document analysis of visa and immigration regulations accessed via www.gov.uk

As Table 1 indicates, the categories of family members from outside the EU with family rights in respect of non-EU economic migrants and UK citizens is much narrower than for EU migrants, restricting their rights to establish a family of choice in the UK. Moreover, where there has been comparative breadth, namely in the inclusion of extended family members, recent changes have seen a tightening. Thus, while until the 2012 reforms to the family migration route, those entitled to enter and reside permanently as ‘adult dependants’ of UK citizens from outside the EU, under the Adult Dependent Relatives (ADR) rule, applied to parents, grandparents and other dependent relatives (sons, daughters, sisters, brothers, aunts and uncles) of UK citizens, the route is now closed to uncles and aunts.

The conditionality noted above in the categories of EU migrants entitled to reside in the UK, that is, to be recognised as ‘qualified persons’, also conditions the family life of those UK citizens with EU family members, since only those EU citizens with a labour market attachment are permitted to reside unconditionally. This has implications for those, most likely predominantly female, EU migrants partnered with UK citizens and engaged primarily in unpaid care work (Shutes, Reference Shutes2016). The definition of what constitutes labour market attachment for EU migrants, however, can also potentially be more or less restrictive (Shutes, Reference Shutes2016). Changes in the UK since 2014 designed to reduce the numbers of EU migrants, including the introduction of a ‘compelling evidence of genuine prospects of work’ test for EU jobseekers after three months in the UK and a ‘minimum earnings threshold to have work classified as work’, have narrowed further the categories of EU citizens entitled to reside unconditionally in the UK (O'Brien, Reference O'Brien2015), with not only additional gendered, but also classed, effects, stemming from inequalities in labour market integration and security (O'Brien, Reference O'Brien2016; Puttick, Reference Puttick2015). This represents a further lever limiting the right to a family of choice for those UK citizens with EU family members.

Conditions of circumstance and conduct

Table 2 sets out the conditions of circumstance and conduct that further govern migrants’ and citizens’ family rights in respect of non-UK citizen family members. Looking firstly at non-EU economic migrants, we see that just as wealth and income condition their rights of entry, residence and settlement, so too they condition their family rights. Thus, for most categories of PBS migrants entitled to bring family members to reside with them (all but Tier 5 Youth Mobility migrants), this is conditional on meeting a maintenance requirement ranging from £630 (Tiers 2 and 5) up to £1890 (Tier 1 – entrepreneurs) per dependant and, since 2015, each dependant also incurs a health-care surcharge of £200 per annum. A condition of conduct common to all PBS migrants and their family members for residency purposes is self-sufficiency, enforced through the ‘no recourse to public funds’ rule (i.e. no entitlement to non-contributory or income-related benefits and housing and homelessness-related support). Via this condition, the economic responsibility for living a co-territorial family-life is entirely individualised for non-EU economic migrants. This may help account for the observed variations in the number of dependants brought per main PBS applicant: between 2011 and 2015, for every visa granted to main applicants there were 2.2 dependant visas for Tier 1, 0.7 for Tier 2 and only 0.04 for Tier 5 (Blinder, Reference Blinder2016: 9). Conditions of circumstance attached specifically to the dependants of Tier 1 and Tier 2 PBS migrants who have a route to settlement have also been tightened in line with the main PBS migrant, such that in July 2012 the minimum length of time they are required to live in the UK to qualify for settlement was extended from two to five years. Settlement is now conditional on passing a ‘Life in the UK’ and an English language test. Dependants must also have been self-sufficient, and, except in cases of domestic violence, maintained their partnership with the PBS migrant, for those five years, and must demonstrate an intention to continue the relationship after the award of settlement. Such conditions enforce high levels of dependency in non-EU migrant families, rendering women in particular vulnerable to exploitation and abuse, and conditioning their ability to live their family of choice.

UK citizens’ rights to sponsor partners and children from outside the EU to reside in the UK have also become sharply conditioned by income, with classed and gendered effects. In 2010, a requirement was introduced for overseas partners to pass an English test for temporary residence. This had implications for those, especially women, living in rural areas with no available tuition or unable to afford classes. 2012 then saw the introduction of a new minimum income threshold of £18,600 gross per annum, with a higher threshold for any children sponsored: £22,400 for one child and an additional £2,400 for each further child. Prior to that sponsors had been required to demonstrate their ability to maintain and accommodate themselves, their partner and any dependants, without recourse to public funds, with the test set at the Income Support rate, equating in 2011 to a post-tax income of £5,500 per year, excluding housing costs, for a couple with no children. It is not only that the maintenance requirement was increased so significantly but also that what is permissible as eligible income has become more restrictive. Pre-2012, the couple could provide evidence of sufficient independent means, the employment income of either or both parties could count, as could their employment prospects and, where a couple could not meet the maintenance requirement, they could provide evidence of support from other family members. Under the new rules, the overseas partner's prior or prospective earnings are excluded, as is third party support (APPGM, 2013). The new threshold is hard to meet: 41 per cent of UK citizens in paid work in 2015 did not earn enough to sponsor a partner, increasing to 51 per cent for sponsorship of a partner plus one child and 57 per cent if two children. For women, young people and those without a degree the rates are even lower at 45, 47 and 47 per cent respectively (Sumption and Vagas-Silva, Reference Sumption and Vagas-Silva2016). Unsurprisingly, the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Migration (APPGM) inquiry into the impact of the changes found evidence of a decline in the number of partner visas issued and an increase in the number of refusals (2013: 19–20). There is also evidence that the route has become more feminised since 2012, with women comprising 75 per cent of migrants admitted as partners in 2014 (Blinder, Reference Blinder2016: 6–7); a further indication that UK women's ability to form a family of choice with non-EU family members has become particularly restricted (Sirriyeh, Reference Sirriyeh2015). The minimum income threshold is applied again if the overseas spouse or partner applies for settlement although, at this point, the overseas spouse or partner may count their income towards the threshold. As in the case of non-EU migrants, settlement is now only available after five years residency (previously two years), and has the same conditions attached, raising similar issues in terms of enforced dependencies.

The 2012 changes also tightened the conditions of circumstance and conduct attached to bringing parents and grandparents to the UK. Under the old rules, parents or grandparents aged 65 or over were eligible to apply for an ADR visa if they were wholly or mainly dependent on the UK-based family member for money, did not have other close relatives in their country who could support them, and could be adequately maintained in the UK without recourse to public funds and housed in the accommodation of the UK sponsor. Since 2012, relatives must demonstrate that they ‘as a result of age, illness or disability, require long-term personal care to perform everyday tasks . . . [and are] . . . unable even with the practical and financial help of a sponsor to obtain a required level of care in the country where they are living because either it is not available and there is no person in that country who can reasonably provide it or it is not affordable’ (Home Office, 2012). Conditions of conduct now go beyond the requirement for the UK sponsor to maintain and accommodate without recourse to public funds those relatives granted entry, to include also responsibility for their ‘care’ (Home Office, 2012). The APPGM enquiry into the ADR changes concluded the route is now ‘all but closed’ (2013: 7). This view is borne out by data on the rate of applications granted, which declined from 65 to 19 per cent between 2010 and 2014 (UK Visas and Immigration, 2016). UK citizens with parents and grandparents overseas and in need of care, must now either provide that care from a distance, or leave the UK to look after them at home. In this case, while income is largely irrelevant, because of gendered expectations around the hands-on provision of care, women are likely to be particularly impacted.

Increased conditions of circumstance also condition EU migrants’ family choices in classed and gendered ways by restricting their access to state welfare, including to some of the most important components of family support in the UK family welfare system for those on low-incomes (O'Brien, Reference O'Brien2015; Puttick, Reference Puttick2015). Restrictions introduced in 2014, ahead of the EU referendum, targeted EU job seekers, and included the introduction of a three-month waiting period for Job Seekers Allowance (JSA), Child Benefit and Child Tax Credit, a time limit on entitlement to JSA of three months (previously six) and exclusion from entitlement to Housing Benefit (HB). Thus, just as in the case of non-EU migrants and UK citizens, some categories of EU migrants – i.e. those in a marginal labour market position – are expected to bear the economic costs of a co-territorial family-life themselves. Moreover, as O'Brien (Reference O'Brien2015: 115) explains, there are significant dependency implications for the partners – especially unmarried – of EU migrants affected by some of these changes, specifically the loss of entitlement to HB.

Conclusion

The family rights attached to migration are clearly differentiated between non-EU citizens, EU citizens and UK citizens. ‘Behind the apparent simplicity of binaries such as ‘migrant’ and ‘non-migrant’ / ‘citizen’ and ‘non-citizen’ / ‘EU migrant’ and ‘British national’, however, lies a much more complex and nuanced picture’ (Kilkey, Reference Kilkey, Foster, Brunton, Deeming and Haux2015: 49). Bonjour and Kraler (Reference Bonjour and Kraler2015: 1412–3) observe:

[F]amily migration policies are different from other migration policies, in that they concern not only ‘outsiders knocking at a state's doors and requesting entry’ but also the ‘moral claim of insiders,’ people living within state borders who ask to be united with their family . . . The more the person requesting family reunification is considered an insider, a ‘member’ who belongs to the nation, the stronger his or her claim to be entitled to live his or her family-life on national territory . . . Accordingly, many states grant privileged family migration rights to citizens. . . (emphasis added)

Yet, their observation does not quite fit the UK picture, where UK citizens’ family migration rights – ranking the least generous among 38 high-income countries (MPG, 2015) – are more conditional than those of non-UK citizens, both from within and outside the EU. In particular, as a result of increasing conditions of circumstance and conduct in relation to income, English language and self-sufficiency, the right to a family of choice for UK citizens with overseas partners and/or children is highly ordered by socio-economic status which, because of gendered labour market inequalities, disproportionately penalises women. In contrast, for EU citizens the right to a family of choice, albeit with limitations and conditions, has been comparatively expansive and unrestricted, and the state has carried financial responsibility for family members accompanying EU migrants as though they were UK citizens. Policy developments in recent years, however, have deepened the historical privileging within EFM of those with a strong attachment to the labour market, with both classed and gendered impacts for family rights.

Such developments, as well as the increasing conditionality attached to the family rights linked to migration of non-EU and UK citizens, signal the potential direction of travel for family rights within a post-Brexit migration regime. Assuming a ‘hard Brexit’ entailing no EFM, the UK government will need to balance its ‘tens of thousands’ target with the demands from many employers to maintain the supply of migrant workers, both low- and high-skilled. Subjecting future EU migrants to the PBS could help manage this tension, especially if Tier 3 for temporary unskilled workers is opened. EU migrants will thus experience the same conditionality in family rights as non-EU citizens. Here, current patterns of stratification within categories, rather than between categories, are instructive. These point to a continuum: at one end, the ‘brightest and the best’ – predominantly men – are allowed to configure their family of choice through the migration process but at their own individual risk in terms of the economic costs of supporting family members in the UK; at the other end, a more ‘disposable’ (Bauman, Reference Bauman1998) class of migrants – among which women can be expected to predominate – is granted only temporary permission to stay, treated as individual economic units of labour, with no rights to live their family of choice, and assumed to manage family-life transnationally.

Meanwhile, what the rights of existing EU migrants in the UK post-Brexit will be remains deeply uncertain. In this context, some who are eligible are applying for settlement but, in doing so, they lose the family rights they had as EU citizens. Instead, they become governed as UK citizens by the rules of the family migration route which, as we have seen, are narrower in terms of who counts as a family member and are deeply contingent on socio-economic positioning, with attendant gendered exclusions. In this context new cleavages may emerge among former EU citizens in their capacity to realise a family of choice – for example, between former citizens of the ‘old’ member states and the ‘new’ member states based on their unequal positioning in the UK labour market (Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Khattab and Manley2015). Likewise, how UK citizens who return home with non-UK family members will fare post-Brexit is also unknown. Cessation of EFM implies that their rights too would be governed by the rules of the family migration route, sharply conditioning their rights also to a family of choice depending on their socio-economic and intersecting gendered position.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful for the constructive comments received from anonymous reviewers on an earlier draft of the article.