Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is a mental disorder with a lifetime prevalence of approximately 2%. Reference Angst, Gamma, Endrass, Hantouche, Goodwin and Ajdacic1 Given that 50% of OCD symptom variability in twin studies is attributable to non-genetic environmental factors, Reference Samuels2 it is pertinent to consider environmental risk in the aetiology of the disorder. Stressful and traumatic life events have been linked to OCD symptoms. Reference McKeon, Roa and Mann3–Reference Selvi, Besiroglu, Aydin, Gulec, Atli and Boysan7 Moreover, childhood trauma, particularly emotional abuse, emotional neglect and physical neglect have been associated with OCD symptoms in children from community samples, and also children in treatment. Reference Lochner, du Toit, Zungu-Dirwayi, Marais, van Kradenburg and Seedat8 Additionally, interaction between environmental and genetic factors has been shown to increase the odds of having OCD in those who have experienced childhood emotional abuse. Reference Hemmings, Lochner, van der Merwe, Cath, Seedat and Stein9

OCD is associated with differences, compared with healthy participants, in corticostriatal and thalamic brain regions, as well as temporoparietal regions pertaining to the affective and executive functioning circuitry. A recent meta-analysis reported volume reductions in the medial orbitofrontal, anterior cingulate and temporolimbic cortices, and larger brain volumes in the striatum and thalamus. Reference Piras, Chiapponi, Girardi, Caltagirone and Spalletta10 Larger volume in these regions has been shown both in sophisticated structural brain imaging analyses, using multivariate feature selection method based on the analysis of the sign consistency of voxel weights across bagged linear support vector machines Reference Parrado-Hernandez, Gomez-Verdejo, Martinez-Ramon, Shawe-Taylor, Alonso and Pujol11 and in traditional techniques using standard general linear models (GLMs). Reference Tan, Fan, You, Wang, Dong and Wang12 Furthermore, the detection of larger brain volume in these regions is associated with OCD symptoms and alterations in executive functioning Reference Spalletta, Piras, Fagioli and Caltagirone13 that may reflect larger brain plasticity as a result of the regular employment of compensatory cognitions.

Smaller brain volumes are also observed in OCD compared with healthy participants, for example, smaller anterior cingulate volume may be associated with OCD symptoms Reference Tang, Li, Huang, Jiang, Li and Wang14 and smaller temporal lobe volume with obsessional beliefs. Reference Alonso, Orbegozo, Pujol, Lopez-Sola, Fullana and Segalas15 Confirming these findings, a recent large multicentre mega-analysis of voxel-based morphometry (VBM) studies comparing 412 adults with OCD v. 368 healthy controls Reference de Wit, Alonso, Schweren, Mataix-Cols, Lochner and Menchon16 showed that patients with OCD had smaller frontal grey and white matter. Additionally, in comparison to the healthy group, patients with OCD had smaller dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate and insular cortex volumes, and larger bilateral cerebellar volumes, as well as age-related volume increases in putamen, insula and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), and decreases in bilateral temporal cortex volume. These brain regions are involved in cognitive regulation of emotion, and awareness of bodily sensation, particularly associated with anxiety. The authors further suggest that age-related volume increases may reflect neuroplasticity associated with chronic compensatory cognitions and/or ruminations in OCD, and that volume reductions may highlight neurotoxic effects. Together, current structural brain imaging studies implicate both the affective and executive functioning neural circuitry in the underlying mechanisms that contribute to a variety of OCD symptoms.

Altered brain morphology in those with OCD Reference van den Heuvel, Remijnse, Mataix-Cols, Vrenken, Groenewegen and Uylings17 has been shown, yet it is not clear how environmental factors, such as early-life adversity, are associated with underlying differences in brain regions. Studies have linked early-life adversity to OCD symptoms Reference Carpenter and Chung6–Reference Lochner, du Toit, Zungu-Dirwayi, Marais, van Kradenburg and Seedat8,Reference Belli, Ural, Yesilyurt, Vardart, Akbudak and Oncu18–Reference Lochner, Seedat, Hemmings, Kinnear, Corfield and Niehaus20 with some evidence of a gene–environment interaction for the influence of childhood trauma on the development of OCD symptoms. Reference Hemmings, Lochner, van der Merwe, Cath, Seedat and Stein9 A total of 12 VBM studies to date have examined the effects of childhood trauma on brain volume in other cohorts, but none in OCD. Reference Lu, Gao, Wei, Wu, Liao and Ding21–Reference Frodl, Reinhold, Koutsouleris, Reiser and Meisenzahl32 Therefore, we examined whether early-life adversity is associated with OCD in adults and its association to brain volume differences when compared with healthy controls.

Method

Participant recruitment, selection and screening

South African White individuals from the Western Cape region, who were either primarily Afrikaans or English-speaking, with a diagnosis of OCD only (e.g. those with comorbidities were excluded during the initial screening (n = 21)) were recruited through physician referral, media advertisements and the Mental Health Information Centre of Southern Africa (MHIC) (the OCD group). Age-, gender- and ethnicity-matched healthy control participants (n = 25) (the HC group) were selected based on individuals who had self-reported home languages of English and/or Afrikaans. Participants were included if they were between the ages of 18 and 65 years. Demographic data, including age at the time of the brain scan, were obtained from all participants, as well as age at onset and psychotropic treatment status for patients with OCD using clinical interview. Patients were either psychotropic medication-free or on psychotropic medication that was (a) limited to a single psychotropic medication from the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class of agents, (b) administered at a steady dose that was not higher than the optimal dose for OCD for the particular agent (e.g. 60 mg of fluoxetine), (c) taken for at least 2 months (8 weeks) and (d) that was stabilised according to the treating psychiatrist.

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview Plus (MINI Plus) – version 5, Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs and Weiller33 a structured diagnostic interview developed for DSM-IV and ICD-10 psychiatric disorders, was administered by a registered clinical psychologist for diagnostic purposes. The Structured Clinical Interview for Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Disorders (SCID-OCSD) Reference du Toit, van Kradenburg, Niehaus and Stein34 was also administered by the clinician to assess the presence of comorbid putative obsessive–compulsive spectrum disorders, so that only cases without comorbid disorders would be included in our study. This procedure lengthened the recruitment period but was deemed necessary to ensure a homogeneous sample with OCD for the purposes of brain measurement and clinical confounds. The study did not, however, examine the subtypes of OCD (e.g. checking/counting, contamination/mental contamination, hoarding, ruminations/intrusive thoughts) because the study number during the recruitment period was small and we rather aimed to first examine global OCD symptomatology and the associations with early-life adversity and the effects on brain volume. Participants with a significant history of neurological disease, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, other psychotic conditions or a history of substance dependence were excluded from the study.

The Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) was used to assess of the severity of obsessive–compulsive symptoms. Reference Goodman, Price, Rasmussen, Mazure, Fleischmann and Hill35 Patients with a diagnosis of OCD only (e.g. without other comorbidities) were included if they were at least moderately symptomatic on the Y-BOCS, i.e. if they had a Y-BOCS total score > 16. The Y-BOCS is a clinician-rated 10-item measure of the severity of symptoms of OCD; each item is rated from 0 (no symptoms) to 4 (extreme symptoms), with a total range of 0–40 and separate subtotals for the severity of obsessions and compulsions. The scale has good interrater reliability, validity and a high degree of internal consistency among all items. Reference Goodman, Price, Rasmussen, Mazure, Fleischmann and Hill35

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (short form) (CTQ-SF) Reference Bernstein and Laura36 was used to assess five types of negative childhood experiences, namely physical abuse, physical neglect, emotional abuse, emotional neglect and sexual abuse, in both the OCD and control groups. Each item was rated from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). Total scores ranged from 5 to 25 for each type of trauma. Additionally, for secondary statistical analyses, we calculated z-scores for the total CTQ score, and to account for high and low total CTQ scores we separated those scores that were either two standard deviations above (for high CTQ) or below (for low CTQ) the mean.

The protocol was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee at Stellenbosch University, and all participants provided written, informed consent after being presented with a complete description of the study.

Magnetic resonance imaging image acquisition

Magnetic resonance imaging was performed on a 3T Siemens Allegra scanner at the Cape Universities Brain Imaging Centre (CUBIC), Tygerberg. MPRAGE T1 images were acquired with the following parameters: repetition time = 2300 ms, echo time = 3.93 ms, inversion time = 1100 ms, spatial resolution of 1.0× 1.0×1.0 mm3; 160 slices, matrix size 179×256, flip angle 12°.

Data pre-processing

Images were initially visually inspected for artefacts or structural abnormalities. Participants with general magnetic resonance imaging artefacts (e.g. image distortion) were excluded from subsequent analyses. First, each structural image was manually realigned to the anterior commissure, as well as the orientation of the head along pitch, roll and yaw dimensions. Next, using the VBM8 toolbox add-on in conjunction with SPM8 and Matlab (dbm.neuro.uni-jena.de/vbm/), the default settings images were co-registered to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI_avg305T1) template, which was then segmented according to grey matter, white matter and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tissue probability maps. The resulting images were spatially normalised into the MNI space using an affine spatial normalisation. Finally, images were smoothed with an isotropic Gaussian kernel of 8 mm full width at half maximum (FWHM). Before analyses in VBM, we extracted millilitre volumes of total grey matter, white matter and total intracranial volume using SPM8. We also extracted millilitre volumes for regions of interest (ROI): anterior cingulate, insula, cerebellum, putamen, parahippocampal gyrus, temporal lobe and fusiform gyrus, according to a recent mega-analysis Reference de Wit, Alonso, Schweren, Mataix-Cols, Lochner and Menchon16 using Pickatlas templates (http://fmri.wfubmc.edu/software/PickAtlas).

Statistical analyses

Analyses of group differences and frequencies of demographic variables between patients with OCD and healthy controls were conducted using t-tests and χ2-tests in SPSS (www.ibm.com/software/analytics/spss/). To run these analyses, parametric assumptions were checked for normal distribution (P-P plots) and homogeneity of variance (Levene's test), and non-normalised scores were log-transformed in SPSS. VBM analyses were performed using SPM8 (www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) using a GLM approach. First, 22 analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted to assess the main effects of group (OCD, HC) and childhood adversity (high, low), and interaction with brain volume data, using age, gender, education status and total matter volume (grey matter+white matter) as covariates of no interest. We chose not to use total intracranial volume (grey matter+white matter+CSF), as some report that SPM8 over estimates CSF values. Reference Nordenskjöld, Malmberg, Larsson, Simmons, Brooks and Lind37 As noted earlier, childhood adversity scores were categorised as either high or low, and calculated by creating standardised z-scores of the total CTQ scores, and then creating two groups of scores: those with at least two standard deviations either above (n = 11) or below (n = 8) the mean. The total OCD group consisted of n = 21, so that meant that only n = 2 participants were too close to the mean to be included in the ANCOVA. For the low CTQ HC group there was n = 15, and in the high CTQ HC group there was n = 7. The total HC group consisted of n = 25, so only n = 3 participants were too close to the mean. Dichotomising the total CTQ scores meant that we excluded n = 5, and that our ANCOVA analyses to examine the main effects of CTQ and group consisted of a total of n = 41. Post hoc t-tests were conducted using F-statistic brain maps as small volume correction, to assess the direction of any significant differences. Second, in VBM multiple regression analyses, we examined how total and subscale CTQ scores were associated with differing brain volumes in the total group, as well as in the OCD and HC groups separately, also correcting for age, gender, education status and total matter volume. All VBM analyses were family-wise error (FWE) corrected for multiple comparisons, and a 20-voxel threshold was applied.

Results

Demographics, Y-BOCS and CTQ data

The demographic, Y-BOCS and CTQ data are depicted in Tables 1 (for all participants) and 2 (for patients with OCD on v. patients with OCD off psychotropic medication). No significant difference was observed between the OCD (n = 21) and HC (n = 25) groups on age (mean 32 years, s.d. = 10.9 and 31 years, s.d. = 10.9 years respectively), gender ratio or ethnicity; global grey matter (mean 714 ml, s.d. = 70 and 696 ml, s.d. = 72 respectively), white matter (mean 481 ml, s.d. = 45 and 462 ml, s.d. = 58 respectively) or total intracranial volume (mean 1463 ml, s.d. = 114 and 1430 ml, s.d. = 161 respectively), or any of the ROI volumes. Only the physical neglect CTQ subscale score was significantly higher in the OCD (mean score 6, s.d. = 1.7) compared with the HC group (mean score 5, s.d. = 0.6, t = 2.0, P<0.05), with a trend towards a higher total CTQ in patients with OCD (mean 38) compared with healthy controls (mean 33, t = 1.7, P = 0.09). Comparing patients with OCD on (n = 10) and off SSRI medication (n = 11), revealed no significant difference in age, gender ratio or ethnicity; illness severity or age at illness onset and no other brain volume measures or CTQ scores were significantly different between these two groups.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical variables in patients with OCD and healthy controls

| Characteristics | Patients with

OCD (n = 21) |

Healthy

controls (n = 25) |

t | χ2 | d.f. | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 31.0 (10.9) | 32.0 (10.9) | 0.3 | 44 | n.s. | |

| OCD illness severity score, a mean (s.d.) | 22.9 (4.2) | – | – | – | – | |

| Age at onset of OCD, years: mean (s.d.) | 13.9 (6.9) | – | – | – | – | |

| Global brain measurements, ml: mean (s.d.) | ||||||

| Total grey matter volume | 696.4 (72.1) | 713.6 (70.0) | 0.8 | 44 | n.s. | |

| Total white matter volume | 461.7 (57.6) | 480.6 (44.9) | 1.2 | 44 | n.s. | |

| Total intracranial volume | 1429.6 (160.6) | 1463.2 (114.1) | 0.8 | 44 | n.s. | |

| Regional brain measurements, b ml: mean (s.d.) | ||||||

| Anterior cingulate | 9.9 (1.5) | 9.9 (1.6) | 0.1 | 44 | n.s. | |

| Insula | 14.6 (1.6) | 15.4 (1.8) | 1.4 | 44 | n.s. | |

| Cerebellum | 88.5 (11.4) | 91.4 (8.7) | 1.0 | 44 | n.s. | |

| Putamen | 5.9 (0.6) | 6.1 (0.7) | 1.0 | 44 | n.s. | |

| Parahippocampal gyrus | 8.6 (0.8) | 8.9 (0.7) | 1.3 | 44 | n.s. | |

| Temporal lobe | 84.5 (9.2) | 85.7 (8.8) | 0.5 | 44 | n.s. | |

| Fusiform gyrus | 20.6 (2.2) | 21.0 (1.5) | 0.6 | 44 | n.s. | |

| Male, n (%) | 11 (52) | 11 (44) | 0.09 | 1 | n.s. | |

| Education level attained, n (%) | 17.1 | 3 | 0.001 | |||

| Grade 8–10 | 3 (14) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Grade 11/12 | 4 (19) | 9 (36) | ||||

| College | 5 (24) | 3 (12) | ||||

| University | 9 (43) | 13 (52) | ||||

| Ethnicity (based on language), n (%) | 81.8 | 4 | <0.001 | |||

| White South African, Afrikaans speaking | 14 (67) | 19 (76) | ||||

| White South African, equally Afrikaans/English | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | ||||

| White South Africa, English speaking | 6 (29) | 3 (12) | ||||

| Other (e.g. Portuguese, Italian, Spanish) | 1 (4) | 2 (8) | ||||

| Medication use at time of scan, c n (%) | 10 (48) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Fluoxetine | 4 (19) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Sertraline | 3 (14) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Escitalopram | 2 (10) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Paroxetine | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | ||||

| No medication | 11 (52) | 25 (100) | ||||

| Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, mean (s.d.) | ||||||

| Emotional abuse | 9.2 (4.3) | 7.7 (3.8) | 1.3 | 44 | n.s. | |

| Emotional neglect | 9.3 (3.7) | 8.0 (3.3) | 1.3 | 44 | n.s. | |

| Physical abuse | 7.3 (3.0) | 6.4 (1.9) | 1.3 | 44 | n.s. | |

| Physical neglect | 6.1 (1.7) | 5.3 (0.6) | 2.0 | 25 | 0.05 | |

| Sexual abuse | 6.1 (2.5) | 5.4 (1.0) | 1.0 | 25 | n.s. | |

| Total score | 38.0 (12.0) | 32.8 (8.3) | 1.7 | 44 | n.s. | |

OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; n.s., non-significant; tr, trend.

a. As measured with the Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) total score.

b. Regions of interest were selected based on findings from a recent voxel-based morphometry mega-analysis of n = 412 patients with OCD and n = 368 healthy controls (De Wit et al Reference de Wit, Alonso, Schweren, Mataix-Cols, Lochner and Menchon16 ).

c. We re-ran all the analyses excluding the patients who were taking other medication at the time of scan to compare the effects. We report both analyses in the subsequent sections.

Table 2 Demographic and clinical variables in patients with OCD on SSRIs v. those that were non-medicated at the time of the brain scan

| Characteristics | Patients with OCD

(on SSRIs) (n = 10) |

Patients with OCD

(off SSRIs) (n = 11) |

t | d.f. | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 32.3 (10.3) | 29.7 (11.7) | 0.5 | 19 | n.s. |

| OCD illness severity score, a mean (s.d.) | 22.7 (2.6) | 23.0 (5.5) | 0.2 | 15 | n.s. |

| Age at onset of clinical symptoms, years, mean (s.d.) | 13.7 (5.3) | 14.0 (8.4) | 0.1 | 19 | n.s. |

| Global brain measurements, ml, mean (s.d.) | |||||

| Total grey matter volume | 693.7 (54.5) | 698.9 (87.8) | 0.2 | 19 | n.s. |

| Total white matter volume | 484.3 (49.1) | 441.2 (59.0) | 1.8 | 19 | 0.08 (tr) |

| Total intracranial volume | 1452.3 (150.7) | 1408.9 (173.7) | 0.6 | 19 | n.s. |

| Regional brain measurements, ml, b mean (s.d.) | |||||

| Anterior cingulate | 9.8 (1.1) | 9.9 (1.8) | 0.2 | 19 | n.s. |

| Insula | 14.5 (1.3) | 14.8 (1.9) | 0.4 | 19 | n.s. |

| Cerebellum | 87.3 (10.6) | 89.5 (12.4) | 0.4 | 19 | n.s. |

| Putamen | 5.8 (0.7) | 5.9 (0.5) | 0.2 | 19 | n.s. |

| Parahippocampal gyrus | 8.6 (0.5) | 8.6 (1.1) | 0.1 | 14 | n.s. |

| Temporal lobe | 83.7 (8.2) | 85.2 (10.5) | 0.4 | 19 | n.s. |

| Fusiform gyrus | 20.5 (1.7) | 20.8 (2.6) | 0.3 | 19 | n.s. |

| Male, n (%) | 6 (60) | 5 (45) | |||

| Education level attained, n (%) | |||||

| Grade 8–10 | 3 (27) | ||||

| Grade 11/12 | 3 (30) | 1 (9) | |||

| College | 3 (30) | 2 (18) | |||

| University | 4 (40) | 5 (45) | |||

| Ethnicity (based on language), n (%) | |||||

| White South African, Afrikaans speaking | 6 (60) | 8 (73) | |||

| White South Africa, English speaking | 3 (30) | 3 (27) | |||

| Other (e.g. Portugese, Italian, Spanish) | 1 (10) | ||||

| Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, mean (s.d.) | |||||

| Emotional abuse | 8.3 (3.7) | 10.1 (4.7) | 1.0 | 19 | n.s. |

| Emotional neglect | 8.7 (3.9) | 9.9 (3.6) | 0.7 | 18 | n.s. |

| Physical abuse | 6.9 (1.7) | 7.7 (3.9) | 0.6 | 19 | n.s. |

| Physical neglect | 6.1 (1.7) | 6.0 (1.7) | 0.1 | 19 | n.s. |

| Sexual abuse | 5.7 (1.5) | 6.4 (3.2) | 0.6 | 19 | n.s. |

| Total score | 35.7 (10.0) | 40.1 (13.7) | 0.8 | 19 | n.s. |

OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; tr, trend.

a. As measured with the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale total score.

b. Volumes were corrected for total matter volume.

ANCOVA and t-test analyses

No clusters survived FWE correction for multiple comparisons; only uncorrected peak voxel differences were found. Examining difference in brain volume between patients with OCD on and off medication revealed no significant differences (independent of CTQ scores).

Multiple regression analyses

Total CTQ

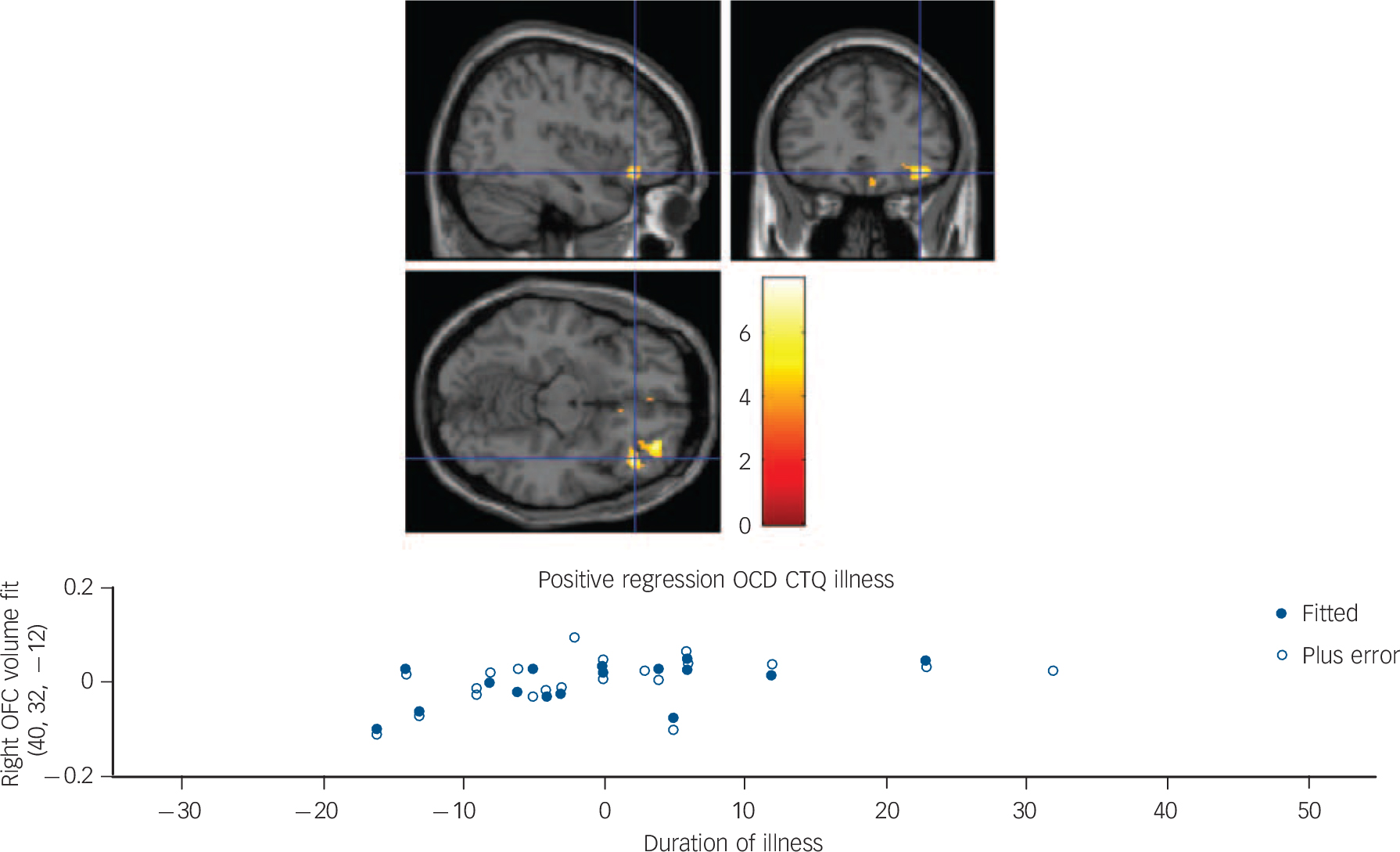

In the total group (i.e. both OCD and HC groups), a positive correlation between total CTQ score and brain volume in the left superior temporal gyrus, Brodmann area 38 (x = −28, y = 20, z = −42, P = 0.07 peak FWE corrected) and in the right fusiform gyrus, Brodmann area 36 (x = 18, y = 0, z = −40, P = 0.09 peak FWE corrected) approached significance (Fig. 1). A regression model undertaken in the OCD group only with total CTQ scores, weighting the regression analyses for duration of illness, revealed a positive association in the right orbitofrontal gyrus, Brodmann area 11 (x = 32, y = 46, z = −10, P = 0.003, cluster FWE corrected). No significant findings were observed in the HC group only (Table 3).

Fig. 1 Top image: Sagittal, coronal and axial slices illustrating a positive multiple regression in the obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) group only, with total Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) score as covariate of interest, and age, gender, education and total matter volume as covariates of no interest. The multiple regression was weighted for duration of illness, resulting in a significantly larger right orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) volume (Montreal Neurological Institute coordinates x = 40, y = 32, z = −120), with the significant cluster corrected for multiple comparisons at the family-wise error P = 0.003. Colour bar represents z-statistic. Bottom image: Fitted right OFC volumes using Statistical Parametric Mapping general linear model and relationship to duration of illness in the OCD group only (current age minus age of recorded onset by clinician).

Table 3 Multiple regression analyses, controlling for age, gender, level of education and total matter volume, with covariates of interest in separate analyses: total CTQ score and subscale scores, also examining the effects of OCD medication on brain volume

| MNI coordinates | Cluster

size Voxels |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain region regression analyses | x | y | z | Z | P (corrected peak) | |

| Total CTQ (whole group) | ||||||

| Positive regression | ||||||

| Left superior temporal gyrus (Brodmann area 38) | −28 | 20 | −42 | 62 | 4.02 | 0.07 |

| Right fusiform gyrus (Brodmann area 36) | 18 | 0 | −40 | 52 | 3.57 | 0.09 |

| Total CTQ (OCD group) | ||||||

| Positive regression (weighted for duration of illness) | ||||||

| Right orbitofrontal gyrus (Brodmann area 11) | 32 | 46 | −10 | 258 | 4.74 | 0.003 (corrected cluster) |

| Physical neglect (OCD group) a | ||||||

| Positive regression | ||||||

| Right cerebellum | 34 | −44 | −34 | 400 | 3.97 | <0.0001 (corrected cluster) |

CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute; HC, healthy control.

a. Physical neglect CTQ scores were examined separately as there was a significant difference between the HC and OCD scores on this CTQ subscale (see Table 1). As an additional check, we examined separately those OCD patients who were not on medication (n = 11) in both the Total CTQ and Physical Neglect (OCD only) regression analyses.

CTQ subscale scores

Conducting within-group regression analyses, again weighted for duration of illness in the OCD and HC groups separately for physical neglect (given that physical neglect was the only CTQ subscale that was significantly different between the groups) (Fig. 2), revealed a positive correlation between physical neglect and brain volume in the right cerebellum (and a trend in the left cerebellum) in the OCD group (x = 34, y = −44, z = −34, P⩽0.0001 FWE cluster corrected; Table 3).

Fig. 2 (a) Sagittal, coronal and axial slices illustrating a positive multiple regression in the obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) group only, with Physical Neglect Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) subscale score as covariate of interest, and age, gender, education and total matter volume as covariates of no interest. This resulted in a significantly larger right cerebellum volume (Montreal Neurological Institute coordinates x = 34, y = −44, z = −34), with the significant cluster corrected for multiple comparisons at the family-wise error (FWE) P = 0.0001. (b) Sagittal, coronal and axial slices illustrating a positive multiple regression in the OCD group who are not on medication, with Physical Neglect CTQ subscale score as covariate of interest, and age, gender, education and total matter volume as covariates of no interest. This resulted in a trend for significantly larger left anterior insula volume (MNI coordinates x = −30, y = 20, z = 10), with the significant cluster corrected for multiple comparisons at the FWE P = 0.065. Colour bars represents z-statistic.

Bivariate correlations between CTQ and ROI volumes

Using Spearman's Rho correlation coefficient analyses to examine whether CTQ total and subscale scores correlate with ROI brain volumes, we found in all patients with OCD only (those taking and not taking medication), that the cerebellum significantly correlated with physical neglect scores (ρ = 0.463, P = 0.004; ROI masks derived from De Wit et al; Reference de Wit, Alonso, Schweren, Mataix-Cols, Lochner and Menchon16 Table 4).

Table 4 Correlation coefficients (Spearman's Rho) between CTQ scores and regions of interest in the OCD group a

| Total CTQ | EA | EN | PA | PN | SA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insula | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Anterior cingulate | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Cerebellum | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.463, P = 0.004 | n.s. |

| Putamen | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Parahippocampal | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Temporal lobe | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Fusiform gyrus | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; EA, emotional abuse; EN, emotional neglect; PA, physical abuse; PN, physical neglect; SA, sexual abuse; P, probability; n.s., non-significant.

a. Regions of interest were taken from the mega-analysis voxel-based morphometry by De Wit et al. Reference de Wit, Alonso, Schweren, Mataix-Cols, Lochner and Menchon16

Discussion

We examined whether the self-reported experience of childhood trauma is associated with brain volume differences in adult patients with OCD compared with health controls. Although there was no difference in the total CTQ score between OCD and HC groups, in the OCD group, there was a significant correlation between increased total CTQ score and larger right OFC volume. Further, there was evidence that the physical neglect score was significantly higher in the OCD group compared with the HC group and that physical neglect positively correlated with larger right cerebellum volumes in the OCD group only.

Previous studies examining the association between brain volumes and OCD symptoms show, as we do here, that patients with OCD have larger brain volumes compared with controls. For example, larger cerebellar and orbitofrontal volumes were also reported in participants with OCD in a recent mega-analysis. Reference de Wit, Alonso, Schweren, Mataix-Cols, Lochner and Menchon16 Additionally, larger brain volume in the striatum and thalamus has been observed in OCD compared with healthy controls Reference Piras, Chiapponi, Girardi, Caltagirone and Spalletta10 as well as larger volume in frontal, temporal and parietal regions. Reference Parrado-Hernandez, Gomez-Verdejo, Martinez-Ramon, Shawe-Taylor, Alonso and Pujol11,Reference Tan, Fan, You, Wang, Dong and Wang12 Furthermore, larger brain volume in these regions is associated with alterations in executive functioning. Reference Spalletta, Piras, Fagioli and Caltagirone13 However, unlike our findings, other studies report smaller brain volumes in OCD compared with healthy participants and in the largest multicentre VBM analysis to date, comparing 412 adults with OCD and 368 healthy controls, Reference de Wit, Alonso, Schweren, Mataix-Cols, Lochner and Menchon16 it was found that patients with OCD had smaller global frontal grey and white matter volumes compared with controls. However, patients with OCD in the mega-analysis and in this study had larger bilateral cerebellar volumes, as well as age-related increases in the putamen, insula and OFC volumes in the mega-analysis, the authors of which suggest that generally, volume increases may reflect neuroplasticity in OCD as a function of compensatory cognitions, whereas decreased volume may indicate neurotoxic effects, such as those related to pathological anxiety.

Our findings expand on work in previous VBM studies of patients with OCD by examining for the first time in OCD how early-life adversity might influence brain volumes. Specifically, in OCD we report that total childhood trauma scores are associated with larger OFC volume, and physical neglect scores with larger cerebellum volume. Moreover, although the previous multicenter VBM study found larger OFC volume as a function of age in the OCD group, we found larger volume in the OFC as a function of duration of illness. OFC function, as well as striatal activation, is linked to the motivation process of evaluating one's environment for salience and valence of objects, especially in relation to immediate self-goals. Reference Kim38 Thus, larger OFC volume in OCD, particularly in relation to duration of illness, may reflect the over-utilisation of compensatory cognitions (e.g. ruminations to evaluate the environment, such as checking, potential contamination, and/or general rumination) that help to reduce pathological anxiety in adults with OCD. This may be particularly important in those who also have prior experience of childhood trauma.

The cerebellum is highly implicated in OCD, particularly for its integration with corticostriatal neuronal processes. Reference Middleton and Strick39 Besides its role in motor function, there is mounting empirical data to implicate the cerebellum in cognition and emotion regulation. Reference Middleton and Strick39,Reference Tobe, Bansal, Xu, Hao, Liu and Sanchez40 Our study supports these findings as we show that early-life adversity, and perhaps physical neglect, is most significantly linked to larger cerebellar volumes and may be associated with greater risk for OCD. OCD has been associated with differences in cerebellar volume, as some studies in those with OCD show normal, Reference Radua and Mataix-Cols41 larger Reference Peng, Lui, Cheung, Jin, Miao and Jing29,Reference Rotge, Langbour, Guehl, Bioulac, Jaafari and Allard42,Reference Pujol, Soriano-Mas, Alonso, Cardoner, Menchon and Deus43 and smaller volumes Reference Yoo, Roh, Choi, Kang, Ha and Lee44 compared with healthy controls. Although OCD has been previously linked to emotional neglect Reference Lochner, du Toit, Zungu-Dirwayi, Marais, van Kradenburg and Seedat45 others have demonstrated a potential link with physical neglect, particularly in terms of the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTT) and the diagnosis of dissociative disorder in those with OCD. Reference Lochner, Seedat, Hemmings, Moolman-Smook, Kidd and Stein46 Furthermore, in a sample of non-psychiatric adolescents, high physical neglect self-report scores correlated with reduced cerebellar volume. Reference Edmiston, Wang, Mazure, Guiney, Sinha and Mayes47 Taken together, it might be that enlarged cerebellar volume is linked to greater neuronal activation in patients with OCD who experience physical neglect in childhood, which may increase the incidence of dissociative disorder and deficits in serotonin transportation in the brain. A genetic predisposition combined with a specific type of childhood trauma might alter the development of the cerebellum, increasing the likelihood that OCD symptoms develop to aid cognition and emotion regulation.

However, it could be that heterogeneity in adults with OCD, such as varying degrees of childhood trauma, may influence cerebellar development and the resulting brain circuitry differences we observe in adulthood. The notion that varying degrees of childhood trauma can have a variable effect on brain volume differences and a resulting OCD diagnosis is supported here, given that there was no significant difference in total CTQ scores between the OCD and HC group. This suggests that degrees of childhood trauma may alter brain development, which can heighten the risk for developing OCD, and that once manifesting, further exacerbates and embeds OCD symptomatology in neural structures. Specifically, the right OFC and bilateral cerebellum are implicated in the neuropathology of global OCD symptoms (not accounting for the subtypes), when considering the experience of early-life adversity.

When considering the total cohort and the general effects of total CTQ score on brain, we observed positive correlations between brain volumes and total childhood trauma scores, suggesting that the more early-life adversity experienced, the greater impact it might have on the developing brain. Yet, it is specifically in the OFC and cerebellar region that the effect of early-life adversity appears more significant for a diagnosis of OCD. Conversely, across the whole group, the experience of early-life adversity was positively correlated with larger left superior temporal gyrus and right fusiform gyrus volumes. In the previous mega-analysis of OCD, Reference de Wit, Alonso, Schweren, Mataix-Cols, Lochner and Menchon16 it was found that patients with OCD had smaller temporal lobes, which may be a risk factor for OCD differentiating adults with early-life adversity that develop OCD from those adults who do not. However, complex interplay between the function of frontotemporolimbic brain regions, genetic susceptibility (e.g. in the serotonin transporter gene) and early-life experiences likely determines neural development across the lifespan that contribute to the onset of OCD symptoms.

Various strengths and limitations must be considered when interpreting these data. First, although we took steps during clinical interviews to select only those volunteers who had no other comorbid disorders (e.g. depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder), it meant that in the time allotted for recruitment we had limited numbers of participants. Related to this, we had limited statistical power to demonstrate significant differences in our ANCOVA analyses, only significant regressions, which might also be linked to there being high variance in the scores, particularly the CTQ and its subscales. Furthermore, we did not examine the effects of subtypes of OCD on brain volume differences, but rather, global OCD scores. Nevertheless, in a small cohort we have progressed the findings by examining for the first time in a brain imaging study the link between early-life adversity, OCD and brain volumes in the right OFC and bilateral cerebellum.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.