… [T]he gates of India were beyond reach, yet the King’s sword pointed the way to them.

Franz Kafka, ‘Der neue Advokat’.Footnote 1

Introduction

A. R. Antulay could not have imagined better results in the by-election of November 1980. At the same time, he acutely understood that his victory was buoyed by the national mood and not by any power base of his own: the general elections earlier that year had been highly favourable for his party, the Indian National Congress (I), which had roared back to power under a resurgent Indira Gandhi.Footnote 2 It had been Gandhi herself who had first tapped Antulay to become chief minister of Maharashtra, a position that he had now secured electorally with an astonishing 87 per cent of the vote.Footnote 3 Even so, as a Muslim leader in a mostly Hindu state where the Hindu Right was on the rise, Antulay knew that he would need to capitalize on the momentum to ingratiate himself with voters.

He soon hit upon an idea. Speaking to reporters during an impromptu trip to London a week later, he announced to the world his quixotic goal: to return to India a historic sword that now hung on a wall of Buckingham Palace. This sword, he maintained, was in all likelihood the Bhavani Talvar, the favourite weapon of the great warrior-king and Maharashtrian icon Shivaji (r. 1674–1680). ‘The sword belongs to the nation and it must come back to the nation’, he declared, promising that by Maharashtra Day (1 May) it would return to the land from which it had been unjustly taken.Footnote 4 His political opponents were unpersuaded. Morarji Desai, whose coalition had four years earlier temporarily unseated Gandhi and installed him as prime minister, rhetorically asked reporters against whom exactly Antulay intended to use the sword.Footnote 5 He would never have the chance to find out. Not only did the British government decline Antulay’s request, but a corruption scandal would lead to his resignation within a year. Antulay was out of office, and the sword was still outside India. And so, it seemed, the affair ended.

But by 2007, the sword had caught the attention of another chief minister—this time in neighbouring Gujarat. ‘I will bring back the “Bhawani” sword of Chhatrapati Shivaji from Britain’, Narendra Modi vowed, framing the task as a sequel to his successful efforts to return the ashes of the revolutionary lawyer and journalist Shyamji Krishna Varma from Geneva to his native Gujarat in 2003.Footnote 6 A Hindu nationalist and vociferous Congress opponent, Modi embodies a very different kind of politics than does Antulay (though he has, like him, thus far failed to deliver on his promise, either as chief minister or in his current post as prime minister). We must ask, then, how two figures who share almost no ideological intersection came to regard a sword as a critical issue for both Maharashtra and the Indian nation as a whole. What, moreover, were they hoping to achieve by making it one?

This article is an answer to these questions. By moving chronologically from the time of Shivaji to the present, it locates Antulay and Modi’s demands within a long line of attempts to locate and possess the Bhavani Talvar. These attempts, it argues further, seldom seek the actual sword so much as a means to steer, and ideally to claim, the legacy of its revered owner. But before examining this history, we must consider a tendency (exhibited by both Antulay and Modi) to privilege the Bhavani Talvar to the virtual exclusion of Shivaji’s other swords.Footnote 7 Though most of the individuals in this study accept that a military leader of Shivaji’s stature would have had several swords, almost all have their sights on the Bhavani Talvar, presumably on the assumption that none of his other weapons could deliver such rich political returns. At the same time, many have been reticent even to acknowledge that his other swords might survive, as if their mere existence threatens the exclusivity of their claim to Shivaji himself.

In tracing the transition from Maharashtra to London and from multiple swords to the singular, this article lays particular emphasis on the late colonial and post-colonial periods. These years saw a sharp increase in the public’s fascination with Shivaji in entertainment, literature, and politics, and with the objects and sites to which he was connected.Footnote 8 It was within this context that three main contenders for the Bhavani Talvar rose to the fore. I present each of these as case studies, illustrating how contemporary discourses around Shivaji were transferred to his sword(s); at the same time, I underscore how and explain why the one in London has become essentially synonymous with the Bhavani Talvar, despite its dubious provenance and the no less plausible claims of its rivals. Ultimately, I suggest that the London sword has functioned more effectively than the other two as a metonym for the loss and potential recovery of the Indian nation, a quality that has maximized its champions’ ability to orient Shivaji’s legacy towards their goals. I should add that though I weigh in on the debates I explore, I have no interest in resolving them. The identification of Shivaji’s true sword—or swords—is an important matter but not the concern of this article. Instead of analysing the merits of each case, I aim to interrogate the narratives that support them and the kind of work these perform, and to argue, in short, that a sword can be as effective a weapon in the public sphere as it is on the battlefield.

A goddess’s gift: The legend of Bhavani and a tale of three swords

In the autumn of 1659, a leading general of Bijapur, Afzal Khan, prepared to lead his army in pursuit of the enemy. A decisive victory was essential: Bijapur, one of the great sultanates of the medieval and early modern Deccan, now faced two existential threats. The first was the southward ambitions of the Mughal empire, the most powerful of its long-standing rivals. The second was more recent but no less formidable. So rapidly had a certain Shivaji Bhonsale, the son of a regional military leader, expanded his territories that he was now the more pressing concern for the Bijapur court, and it was against him that Afzal Khan was marching. According to the Śivabhārata—a retelling of the lives of Shivaji, his father, and grandfather in the form and language of a classical Sanskrit epic—the Bijapuri general encountered several strange meteorological and astronomical phenomena as he embarked on his campaign. After engaging Shivaji in a series of cat-and-mouse skirmishes, Afzal Khan entered Tuljapur, a city closely associated with his adversary’s family deity, Bhavani. It was here, the Śivabhārata continues, that Afzal Khan ordered an attack on Bhavani’s temple, smashing its mūrti, or icon, and slaughtering a cow on its steps. Determined to arrest further destruction, the goddess herself appeared to Shivaji, whom she claimed to have met long ago:

Probably written largely at the court of Shivaji himself, Paramānanda’s Śivabhārata is a literary manifestation of Shivaji’s far-reaching project to connect his rule with India’s legendary past.Footnote 10 These verses illustrate exactly this: building upon the text’s contention that Shivaji is an avatar of Vishnu, Bhavani informs him of their relationship during the time of one of Vishnu’s earlier avatars, Krishna. Appearing then as a daughter of Krishna’s foster-father, she had allowed herself to be confused with the infant Krishna and thereby thwart the evil Kamsa’s attempt to murder him. This sacrifice allowed Krishna to live on and kill Kamsa himself. Bhavani tells Shivaji that this moment has come again, for Vishnu (now appearing as Shivaji) must once more destroy Kamsa (now appearing as Afzal Khan), who seeks another attempt on his life. Bhavani once more has a pivotal part to play: just as she had protected Krishna in the form of a child, she will now protect Shivaji in the form of a sword.Footnote 11 The verses that follow relate a version of a story familiar to every Maharashtrian schoolchild, in which Shivaji kills Afzal Khan just before Afzal Khan intended to strike him.Footnote 12

Since today most retellings of this final encounter involve Shivaji using something akin to brass knuckles and his sword only secondarily (if at all),Footnote 13 the sword itself is no longer immediately associated with the killing of Afzal Khan. Its link to Bhavani has nevertheless held firm, giving the weapon its name: the Bhavani sword, or the Bhavani Talvar.Footnote 14 The story of the goddess’s appearance to Shivaji would become a favourite topic of bakhars (a genre of early modern Marathi prose) during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and of plays, films, and other media from the colonial period onwards. As with narratives about Afzal Khan, this constant retelling has produced numerous variations. Some of these downplay the Vaishnavite elements in the Śivabhārata and associate Shivaji and Bhavani with Shiva and Parvati,Footnote 15 while others minimize or altogether omit Bhavani’s theophany and assign the sword a more mundane origin. Emblematic of this kind of origin story is the Śivadigvijaya, a Marathi biography of Shivaji of uncertain date, which relates how Shivaji acquired the sword from the chief of a local clan, the Sawants. Some writers add further texture to this version, noting how the Sawants had taken the sword in 1510 as booty from a Portuguese commander, Diego Fernandes, and later presented it to Shivaji upon his visit to the Saptakoteshwar Temple in Goa.Footnote 16 Many also state that Shivaji paid the Sawants 300 hons (gold coins), though the Śivadigvijaya suggests it was given freely to Shivaji as a gift.Footnote 17

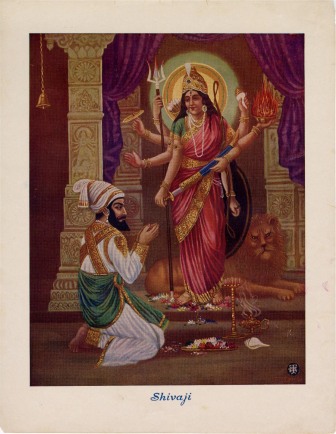

Importantly, even versions that do not assign the sword a divine provenance tend to associate it with divinity. In the Śivadigvijaya, the sword itself speaks to Shivaji and the Sawant chief in a dream, and in almost all accounts Shivaji names it after Bhavani, stores it at her altar, and associates it with her presence. Sometimes the narrative crosses into the supernatural in a manner reminiscent of the legend of Excalibur and the Lady of the Lake.Footnote 18 According to one tradition, Shivaji, upon visiting the temple of Bhavani in Tuljapur, places his newly acquired sword in one of the eight hands of the Bhavani statue. The goddess then appears to her devotee in a dream, returning the sword to him, now encrusted with rubies and diamonds.Footnote 19 This version has been highly popular since at least the nineteenth century, and it is from here that we acquire the image of Shivaji kneeling before the goddess, his arms outstretched in receipt of a divine gift, that appears in paintings and statues across and beyond Maharashtra (see Figures 1 and 2).Footnote 20

Figure 1. Image of Shivaji receiving his blessed sword from the goddess Bhavani. Calendar art from the Oriental Calendar Manufacturing Company, Calcutta, circa 1940s. Source: Author’s own collection.

Figure 2. Presumed cast by V. P. Karmarkar for a panel on the pedestal of an equestrian statue of Shivaji in Pune. Source: H. George Franks, ‘Shivaji, the human king’, in Shivaji souvenir: Tercentenary celebration Bombay, (ed.) Govind Sakharam Sardesai (Bombay: Bombay Vaibhav Press, 1927), pp. 98–99.

The existence of these variants matters much more than their particulars and shows how stories about the sword—much like the sword itself, as we shall soon see—tend towards multiplicity. Still, two important assumptions cut across these variations. The first is that the sword serves as a symbol of Shivaji’s power and a force behind his underdog victories. Even the less explicitly theological versions—such as those that represent Bhavani as an abstracted rather than an overtly supernatural entity—assign qualities to Shivaji that exceed those of ordinary human capacity and are in some way linked to his sword. Second, and running in some ways against the first, is an insistence that the sword is a physical object that exists in the world and can be located within it. The tension between these two assumptions—the one holding that it is transcendental and the other that it is tangible—has been central to the sword’s enduring appeal, inspiring generations of observers and political actors to locate a sword that, though real, has something decidedly otherworldly about it.

Such attempts began in earnest during the colonial period, when fascination with Shivaji rose in tandem with archaeological and historical methods supporting the study of his life. For many Indians during these years, the appeal of Shivaji reflected a yearning for the recuperation of his perceived national—or, for his acolytes in the twentieth century, nationalist—vision, which they maintained British rule had interrupted. Importantly, this was not the kind of nostalgia whereby preoccupation with the past impedes its recovery (as in Freud) nor whereby that past, once revisited, disappoints (as in Kant).Footnote 21 Rather, the gravitation towards Shivaji was productive and largely forward-looking: though built from the shards of an idealized past, it was oriented towards new political horizons that it would, with the gradual rise of Hindu nationalism, ultimately draw near. I want to locate the sword within this milieu, a milieu in which it seemed that the physical sword, like the political spirit of the figure to whom it pertained, could be recovered, possessed, and—within political and social discourse, at least—wielded.

From the colonial period to the present, the search for Shivaji’s sword has drawn rather little from the early historical record, since there is, to my knowledge, no Marathi or Persian source contemporaneous with Shivaji’s death that clearly specifies the fate of the sword described in the Śivabhārata. The most prominent candidates have accordingly been those that can be conceivably linked, whether through their physical features or ownership histories, to places and figures associated with Shivaji. Among the first writers to identify a specific sword as Shivaji’s was the historian and civil servant James Grant Duff, who in 1826 located it in the princely state of Satara, where he himself served as Resident, or the British representative at court.Footnote 22 Relying on local sources and lore available to him in that capacity, Grant Duff claims in his History of the Mahrattas that Shivaji’s sword first fell to his elder son, Sambhaji (r. 1680–1689), in whose possession, he writes, it ‘could not have been better wielded’.Footnote 23 In describing Sambhaji’s imprisonment and execution by the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, Grant Duff weaves together several episodes from Persian and Maratha chronicles, which he also follows in recounting Aurangzeb’s imprisonment of Sambhaji’s own son, Shahu. He departs from the best-known sources, however, by adding that Aurangzeb took custody not only of Sambhaji’s son but also of Sambhaji’s sword. The fate of the two would intersect, he writes further, at Shahu’s wedding:Footnote 24

On this occasion, Aurungzebe, amongst other presents to Shao, gave him a sword he had himself frequently worn, and restored two swords which Shao’s attendants had always urged him, if possible, to recover; the one, was the famous Bhowanee of Sivajee; and the other, the sword of Afzool Khan, the murdered general of Beejapoor, both taken at Raigurh.Footnote 25

Entrusting weapons to his rival’s son—who was still his captive—is not as strange as it might seem, for Aurangzeb may have been grooming a vassal to help him bring Shivaji’s former territories under Mughal control. In any event, the animosity he felt towards Sambhaji (and Shivaji) appears not to have extended to Shahu, whom he granted the title of raja and a manṣab rank of 7,000—two gradations above what he had supposedly offered Shivaji at their infamous attempt at de-escalation in 1666.Footnote 26 Shahu would remain in Aurangzeb’s custody until the latter’s death in 1707, after which he travelled to and was crowned at Satara Fort, taking with him, Grant Duff claims, the Bhavani Talvar, which would henceforth remain in the fort of his ancestors and the care of his descendants.Footnote 27

As with many topics in Maratha history, the identification of Shivaji’s sword is complicated by a dispute over succession. Shahu’s long imprisonment under Aurangzeb left ample time for a rival to emerge, which it did in the form of his four-year-old cousin, Shivaji II (r. 1700–1707)—or, more accurately, in the form of Tarabai, Shahu’s aunt, who served as her son’s regent.Footnote 28 The fascinating political theatre that follows must not distract us here, except to note that after a brief civil war, two dynasties would coalesce and by 1731 tepidly acknowledge the legitimacy of the other: Shahu I (r. 1707–1749) and his successors in Satara, and Shivaji II (r. 1710–1714) and his successors in Kolhapur.Footnote 29 The former would serve as figureheads of the Maratha empire, a polity that would dominate eighteenth-century South Asia before falling to the British East India Company in 1818.Footnote 30 Both to appropriate the bureaucratic structures of the defunct empire and to court favour with the Marathas, who continued to hold Shivaji’s heirs in high esteem, the British thereupon established Satara and Kolhapur as distinct princely states, a status that granted them autonomy from British India while still subjecting them to its oversight.Footnote 31

These details matter because by the end of the nineteenth century Kolhapur would become associated with a rival sword that its proponents claimed had been in that city since some time shortly after Shivaji’s death.Footnote 32 It would enjoy a strong, though by no means uncontested, claim to be the true Bhavani Talvar well into the modern political era, where it has become the object much fetishized by politicians like Antulay and Modi. That both swords bear a close connection to Maratha princely states distinguishes them from a third contender that appeared during the early decades of the twentieth century, whose owner, Bomonjee Pudumjee, claimed to have won it at an auction with no knowledge of its earlier history.

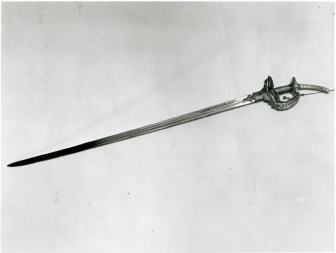

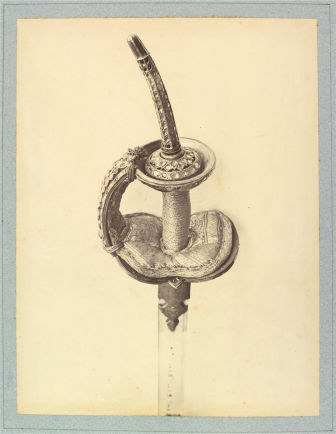

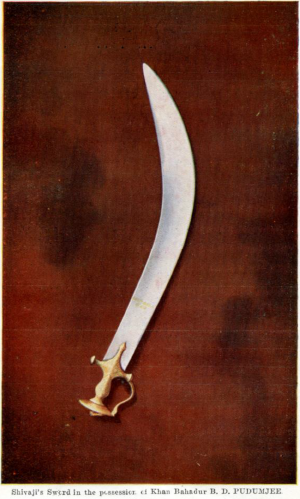

The swords themselves constitute remarkable objects. Those of Satara and Kolhapur are in appearance much alike: typically regarded as being of European manufacture, their long, straight, single-edged blades stem from elaborate hilts that are padded to protect the bearer’s knuckles and attach to a long, thin, curved pommel. The main difference between the two is their size, since the blade of the Satara sword is longer (114 cm) than that of Kolhapur (98 cm). The hilt of the latter, together with its corresponding sheaths, is richly encrusted with rubies, diamonds, and emeralds. Pudumjee’s sword is similarly exquisite, though his lacks gems; shorter than the other two in length (72 cm), the blade is of Maghrebi rather than European provenance and is the only one of the three that is slightly curved. Its sheath appears not to have survived. All swords bear an inscription, with those on the Satara and Pudumjee blades apparently referring to previous owners.Footnote 33

Since these designs and markings have played a part in the various public identifications of the Bhavani Talvar, we should keep them in mind as we examine the histories of each. At the same time, we will see that these features are invoked principally to reinforce or illustrate a case and seldom form the basis of an (effective) argument on their own. Rather than its features, it is the polities and persons with which a sword is associated that have determined whether it gains traction within the public sphere, with links to Shivaji’s celebrated heirs enjoying a particular power.

The fall of the House of Satara: The senior Maratha line and its ‘fine Ferrara blade’

Even after the nominal end of the Maratha empire in 1818, Shivaji’s descendants in Satara continued to enjoy wide public popularity,Footnote 34 such that the sword in their possession was virtually synonymous with the Bhavani Talvar until the middle of the nineteenth century. We have seen that the earliest record of this weapon probably comes from Grant Duff, who had access to documents and anecdotal knowledge difficult to obtain elsewhere. He cites ‘the hereditary historian of the family’ to support his claim that the sword had remained in Satara since Shahu’s death, adding that it was ‘still preserved by the Raja … with the utmost veneration, and has all the honours of an idol paid to it’.Footnote 35 Grant Duff does not offer measurements of the sword but describes it as ‘an excellent Genoa blade’,Footnote 36 a designation that later writers—in all likelihood having read his aforementioned History—would repeat without clarifying its significance (and, in some cases, without having seen the sword).Footnote 37 The records of the hereditary historian to which Grant Duff refers would surely shed more light on his meaning, but since these are not readily available—if indeed they still existFootnote 38—Grant Duff’s own musings may be our best window into a tradition that, whatever its particulars, seemed content and even proud to associate Shivaji with a foreign blade. Grant Duff’s narrative is also critical for understanding subsequent generations’ attitudes towards the Bhavani Talvar, since his views would be disseminated widely through his History, a text that enjoyed a central place in Indian classrooms, particularly in a state-sponsored Marathi translation,Footnote 39 well into the twentieth century. It remains a classic in Maratha history today.

The Satara royal family, together with the Satara sword itself, would have none of Grant Duff’s good fortune. After one raja, Shahaji (r. 1839–1848), died without issue, the newly appointed governor-general of India, the Earl (soon-to-be-Marquess) of Dalhousie, James Broun-Ramsay, refused to acknowledge the legitimacy of the raja’s adopted son and folded the state directly into British India.Footnote 40 Some years later, in 1876, the erstwhile princely state was visited by Katharine Blanche Guthrie, who gives us a fuller description of the sword, noting that it enjoyed pride of place at the foot of a temple to Bhavani and was a ‘fine Ferrara blade, four feet in length, with a spike upon the hilt to thrust with’.Footnote 41 Since Guthrie’s remarks draw heavily on her conversations with local interlocutors, her description would seem to substantiate the existence of a local belief that the blade was European, a tradition that would be consistent, moreover, with the demand for so-called firangi swords in early modern India in general and in Maharashtra in particular.Footnote 42 That Satara still attracted travellers like Guthrie—who gives much space and prominence to the city in her travelogue—attests to its enduring allure nearly three decades after it had disappeared from the map as a princely state. But things were clearly not as they had once been. ‘No fort in Máhratta,’ Guthrie declares, ‘has been more connected with the historical events of many centuries’,Footnote 43 but it was now ‘ruined, the English having effected in an hour what neither time nor the enemy could accomplish’—a reference to the destruction of its outer defences, which were ‘blown into fragments by gunpowder’ after the 1857 Mutiny.Footnote 44 The damage would soon penetrate (what was left of) these outer walls and extend to the palace itself: Jadunath Sarkar asserts that, facing hardship, the royal family opted to siphon off its treasures, many of which ‘found a refuge in Satara palace, but began to be dispersed in the last two decades of the nineteenth century’.Footnote 45 If the palace served as a kind of holding ground for valuable objects before they entered the market, then it is noteworthy that the sword recorded by Guthrie—which was directly in the line of fire and presumably a highly valuable financial asset—would remain.

Soon, the once-grand princely state seemed for many little more than a tragic footnote in the transition from Maratha to British rule. The waning political fortunes of Satara would ultimately damage public perceptions of its sword. If we look ahead to 1929, for example, we read how Bomonjee Pudumjee (about whom much more shortly) and the Maratha historian H. G. Rawlinson drew attention to the Devanagari inscription on its blade, ‘sarkār rājā śāhū chatrapati kadīm avval’ (The lord King Chhatrapati Sahu, foremost of leaders).Footnote 46 This inscription led both observers to conclude that the weapon may have been Shahu’s but not Shivaji’s. That Shahu would have engraved his own name onto the blade of his grandfather’s weapon was for Rawlinson ‘a piece of vandalism of which he was scarcely likely to have been guilty’.Footnote 47 He argues further that Aurangzeb would never have willingly handed over such a powerful object to Shahu.

Such assumptions are hardly airtight. We might ask why, if Shahu sought to attach himself to Shivaji’s legacy—as he surely did—he would not inscribe his name on an object that so readily evoked it. Even in the thaumaturgic world of early modern India, after all, a sword was an instrument of war rather than of magic, and it seems unlikely that Aurangzeb would have believed that putting it into Shahu’s hands would reinvigorate the spirit of his meddlesome grandfather. My point here is not to defend the legitimacy of this sword—which there are good reasons to doubt—so much as it is to illustrate that these studies assume a reader who needs minimal persuasion to dismiss it as Shivaji’s. By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in other words, a rather deflated view of Satara must be factored into negative assessments of its sword, including that of one antiquarian who in 1934 deemed it not ‘of good enough quality to have belonged to Sivaji’.Footnote 48 Directed towards the same object that Guthrie had once so richly praised, such dismissiveness suggests a change not in the sword itself but in the prestige of the polity to which it pertained.

The sword of princes: The junior Maratha line and ‘the Palladium of their house’

Running parallel to the declining fortunes of Satara was the rising visibility of its junior rival. Kolhapur’s social and political ascent was a slow, negotiated process between the Indian public and the colonial state: the former had long held Shivaji’s junior line through his grandson Shivaji II in high esteem—especially in and around the Bombay presidency—but it was only after Satara’s princely status was rescinded that Kolhapur’s real political relevance emerged.Footnote 49 The colonial state recognized as much and established so-called minority administrations over multiple child rajas in the latter half of the nineteenth century, effectively giving it control over Kolhapur’s government until each came of age. This, together with British insistence that one of these was mad and therefore incapable of autonomous rule even as an adult, provoked a strong counter-reaction by an Indian (and especially a Marathi) press eager to defend this last vestige of Maratha glory.Footnote 50 As the Kolhapuri royal family became a site over which the legacy of Maratha rule and the limits of British authority were worked out, the colonial state gradually assigned it further symbolic importance, a process that is actually quantifiable: in the middle of the nineteenth century, its raja was afforded an honorary salute of 17 guns, a number that rose to 19 during the reign of Rajaram II (r. 1866–1870). The most prominent of Kolhapur’s rulers, Shahu IV (r. 1894–1922), was given a full 21-gun salute ‘as a personal honour, in recognition of His Highness’ loyalty to the British Throne’,Footnote 51 thus positioning him at the highest echelon of Indian princes.

Like the family with which it was associated, the sword to which we now turn rose to prominence only slowly, evolving in popular discourse from a sword of Kolhapur, to a sword of Shivaji, to the Bhavani Talvar itself. A now-familiar narrative, and one that holds critical significance for the rest of this article, maintains that Shivaji VI (r. 1871–1883)—the same raja whom British officials would later declare mad—met Albert Edward, Prince of Wales (and the future Edward VII) in 1875 during the latter’s tour of India. As a gesture of loyalty, the narrative continues, the raja presented the prince with the Bhavani Talvar, which had apparently been in his family’s possession all along.Footnote 52 While it is certain that the two royals met and that Shivaji gave Albert Edward gifts—including, in all likelihood, a sword or swords—there is little evidence to suggest that any of these once pertained to the young raja’s ancestor.Footnote 53 Some who argue otherwise have drawn attention to documents from the Kolhapur Durbar, which they claim mention such a sword having been in the armoury in February of that year.Footnote 54 Leaving aside doubts about the whereabouts of these documents, such a reference obviously cannot illuminate what transpired when Albert Edward and Shivaji met some seven months later.

The two would actually meet twice: first at Albert Edward’s lodgings on 9 November 1875 and again at Shivaji’s Bombay residence the following day.Footnote 55 It was probably during the second meeting that the sword in question was given away.Footnote 56 The earliest evidence for this comes from the journalist William Howard Russell, who, after offering a lukewarm assessment of most of the gifts given by Indian princes to the Prince of Wales (‘On the whole the offerings were good without being too fine’),Footnote 57 notes in his diary of the prince’s tour that

The Raja of Kolhapoor, in addition to an ancient jewelled sword and dagger, estimated to be worth 6000 rupees, has assigned a sum of no less than 20,000l. for the admirable purpose of founding a hospital, to be called after the Prince of Wales.Footnote 58

Albert Edward would receive numerous swords in India,Footnote 59 and Russell signals out Kolhapur’s for its artistry and value, not for any association with Shivaji, whom he mentions in several other contexts but not in this one. Indeed, I know of no contemporary account that supports the sword’s having been Shivaji’s; on the contrary, at least one eyewitness, Dighton Probyn, who served as an equerry of Prince Albert Edward during his visit, would insist years later that he ‘would certainly have remembered, had the celebrated sword in question been given to His Majesty’.Footnote 60 Probyn’s long-standing connections to India would have made him knowledgeable about both Shivaji and the many Indian royals who met the prince in Bombay, among whom the raja of Kolhapur would in any case have grabbed his attention as the first royal presented to Albert Edward. As a 12-year-old boy whose neck and turban were covered in jewels, moreover, Shivaji VI would presumably have made quite an entrance—to say nothing of his show-stopping exit:Footnote 61

The Kolapore Rajah went off as he came, in great state, in a grand carriage drawn by four horses, with servants in beautiful liveries of blue and silver, and a magnificent fan-bearer behind wielding a blazing machine to keep the sun away.Footnote 62

The earliest assertion that the sword the young prince gave to Albert Edward belonged to Shivaji occurs only after Albert Edward returned to the United Kingdom, when the objects he received from Indian royals were sent to the India Museum (housed within the South Kensington Museum) for public display. Among these, a court circular stated, were

family or national heirlooms, which nothing but a sentiment of loyalty could have moved their owners to give up: objects so prized as the sword of Sivajee—not Bhowanee, the deified weapon at Sattara, but the sword which has been sacredly guarded for the last 200 years at Kolapoor by the junior branch of Bonslas [emphasis added]. These symbols of the latent hopes and aspirations, or of the despair of nations and once Sovereign families, have been forced on the Prince’s acceptance in a spontaneous transport of loyalty, and their surrender may be fairly interpreted as meaning nothing less than that the people and Princes of India are beginning to give up their vain regrets for the past—and … desire to centre their hopes of the future in the good faith, the wisdom, and power of the British Government.

These words would appear across British papers in June 1876, usually with minor but sometimes more significant variations, especially the omission of the phrase specifying that the object is not the Bhavani Talvar (see Figure 3).Footnote 63 Valuing these royal gifts less for their splendour than for their importance to Indian royalty,Footnote 64 the report equates their bestowal with a kind of submission demanding not just acquiescence to British rule but obsolescence of the pre-British past. Shivaji’s sword illustrates this process: with its utility as a tool of empire exhausted, the sword now derived its value because it lay in the hands of the British monarchy, who in accepting it had agreed to protect the Maratha people as the sword itself once did.

Figure 3. Undated photograph of the London sword. Source: The National Archives, Kew, ref. FCO37/2331.

The details that the court circular includes about the sword’s provenance, though certainly possible, cannot be readily ascertained. Despite the assertion that it had ‘been sacredly guarded for the last 200 years’, there is no record of the family’s earlier relationship with the weapon, no Grant Duff-like testimony asserting that it was once held in a place of veneration.Footnote 65 Even so, these claims aroused little suspicion at the time, and the sword (together with many other objects Albert Edward received during his tour) travelled frequently over the next six years, such that some two million people may have seen it at various places across the United Kingdom (see Figure 4).Footnote 66 The collection notably travelled to Paris for the 1878 Exposition Universelle, at the time the largest instantiation yet of the World’s Fair. In a handbook accompanying the British delegation to that event,Footnote 67 George Birdwood—who had been the head curator of the collection since Albert Edward’s return from India—identifies the arms as its most impressive objects, among which the ‘most interesting of all is the sword … of Sivaji, the founder of the Mahratta dominion in India’.Footnote 68 He considers Shivaji’s career in some detail before discussing the object in language nearly identical to the court circular, of which he (as the chief publicist for the collection) had very likely been an author. It is interesting that Birdwood readily concedes that it is not the Bhavani Talvar, noting (as in the circular) that, ‘The sword in the Prince’s collection is not this deified weapon.’Footnote 69 We will shortly consider how the space for such an interpretation was soon to narrow, but first we should interrogate Birdwood’s reasons for connecting the sword to Shivaji at all. Having concluded his service in India about a decade earlier on account of ‘broken health’,Footnote 70 he was not a personal witness to Albert Edward’s meeting with Shivaji VI. It is unclear, then, whether Birdwood is recording anecdotal information or simply assigning the object the best story he can. Simply put, did the rajas of Kolhapur really regard the sword as ‘the palladium of their house and race’?

Figure 4. Photograph from Samuel Bourne, Prince of Wales Tour of India 1875–6. Vol. 5 (Calcutta: Bourne and Shepherd, 1876), see ‘Sword hilt’. Source: Royal Collection Trust/© His Majesty King Charles III 2023.

That Birdwood wanted to tell a good story is not in dispute. His text is not—as its rather prosaic title, Handbook to the British Indian Section, might suggest—a mere inventory of the Indian pieces included in the British exhibition; it is a sprawling history of India that begins with such grandiose sections as ‘The Settlement of the Old World by the Human Race’ and culminates with the rise of the British empire.Footnote 71 Utilizing the pieces in the British exhibition, it argues that India combines the grandeur of a classical heritage with the promise (through British rule) of a modern resurgence. Since Shivaji stands at the crossroads of early modern and colonial India, and since the surrender of a sword typically signifies the deference of the giver to the receiver, it is little wonder that Birdwood would assign such prominence to a sword bequeathed by the heir of Shivaji to the heir of the British empire. What really matters, in other words, is not whether it is the ‘deified’ sword of Shivaji but that it is the one through which his legacy was transferred to British stewardship.Footnote 72

We should also recognize that the attribution of the sword to Shivaji—unless it stems from some now-lost earlier source—may have been merely a mistake. After all, the sword did belong to a Shivaji, and Birdwood or someone else could easily have misconstrued an object catalogued as the former property of Shivaji VI as being that of his iconic namesake. Still, some measure of wishful thinking was at play, since Shivaji VI gave Albert Edward two other swords that never became associated with Shivaji himself.Footnote 73 We can presume that the sheer ornateness of the ‘sword of Sivajee’ might have attracted Birdwood, just as it had Russell (assuming, of course, that Russell was referring to the same object). The two other swords are also remarkable, but with fewer jewels and lesser detail, neither so readily evokes the richness of the tradition that Birdwood believed Kolhapur had lost and Britain had inherited.

Whatever the sword’s connection to Shivaji, the whirlwind tour that had taken it from Paris to Aberdeen died down in an apparent reflection of flagging European interest.Footnote 74 In India, by contrast, the sword continued to garner attention in newspapers and public life, but there, too, an important shift was underway. Although Birdwood and other observers in Britain had explicitly differentiated the sword given by Kolhapur from its counterpart in Satara, the two were to become increasingly indistinguishable in India. A notable example in this regard are the scattered references to the sword in the 1897 sedition trial of the Indian nationalist Bal Gangadhar Tilak. In recounting Tilak’s use of Shivaji as a political symbol, the advocate-general (representing the state) locates Shivaji’s sword in Satara even as The Times of India—in reporting on his remarks—maintains that, ‘The sword referred to by the prosecution was preserved for a long time at Satara, but it was now in the possession of H. R. H. the Prince of Wales, who was presented with it at the time of his visit to India.’Footnote 75 What both the prosecution and the press share is the notion of a single weapon, a single weapon that, interestingly, has no connection to the raja of Kolhapur.Footnote 76 The omission of Shivaji VI from the narrative around the sword is noteworthy not just because of his once-strong association with the object, but also because Tilak had prominently defended him amid the government’s insistence that he was insane and required a regent. So ardent was Tilak’s defence of the troubled raja that he had been imprisoned for slander against the state in 1882, an episode surely not forgotten by lawyers eager to put Tilak back behind bars, nor by journalists for whom the raja’s highly irregular death in 1883 had offered media gold.Footnote 77 Whatever the reason that the young Shivaji’s connection to the sword was excised from discussions in and about the courtroom, then, it cannot be because he was anything less than an eminently familiar public figure. It seems instead that the narrative then circulating about Shivaji (the Great) and his sword had simply become condensed: what had been two swords had now melded into one, becoming just the sword of Shivaji, or the Bhavani Talvar.Footnote 78

This streamlining seems to me to have been the result of two factors. The first was Shivaji VI’s successor, Shahu IV (r. 1894–1922), a flamboyant reformer whose immense popularity may have guarded against the idea that his house could have parted with an heirloom of national significance.Footnote 79 Still more decisive was probably the fate of the Kolhapur sword itself. Despite its starring role in the 1878 Exposition Universelle, the ‘most interesting of all’ its objects was—to the public at least—simply nowhere to be found by the end of the nineteenth century. With the whereabouts of the sword unknown, determining its location became more pressing than determining its origins. The cachet of Kolhapur may have brought Shivaji’s sword to prominence, but it was the sudden loss of the object itself that sustained interest in, even as it blurred, important details of its history.

After the collections of the India Museum were dispersed in 1879 and exhibitions of its objects gradually petered out, many assumed that the sword had been moved to the British Museum.Footnote 80 Its curators sought to assure the public this was not the case, telling a series of Maharashtrians visitors beginning in 1908 that one weapon was ‘not the real Bhawani sword’ and that objects claimed by some to have been Shivaji’s were ‘not the genuine articles’.Footnote 81 By 1915, the museum clarified its position by stating that it did not possess the Bhavani Talvar and, implicitly, any other sword of Shivaji. S. M. Edwardes, a historian and British civil servant, took the museum at its word and broadened the search. Finding nothing at Windsor Castle, Sandringham House, or Buckingham Palace, he concluded in 1920 that he was ‘quite certain that the famous Sword is not in England [emphasis original]’ and went so far as to doubt whether the Prince of Wales had ever received such an item.Footnote 82 By 1924, he was content to return the search to India. ‘The question still remains “where is now the original Sword Bhavānī?”’, he wondered, speculating whether it might ‘have been taken to Benares’, a reference to the exile of Satara’s last raja to that city.Footnote 83

If statements like those from the British Museum and Edwardes had hoped to deflect further inquiries, they did not. So incessant were Indian visitors’ demands to examine objects at the British Museum that in 1925, John Marshall, the director-general of the Archaeological Survey of India, rather grumpily mused in the margins of yet another request to contact the museum’s curators that, ‘In 1915 the British Museum denied the existence of the sword in their collection, and we may presume that it has not found its way there since.’Footnote 84

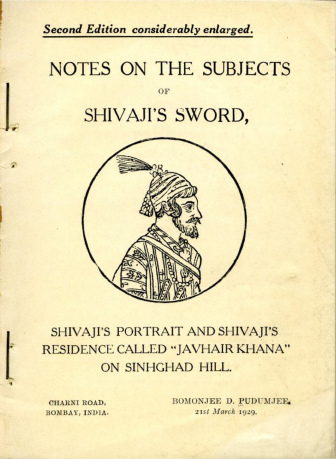

The citizen’s sword: Bomonjee Pudumjee and the democratization of Shivaji

The saga of the London sword was far from over, but for the moment, at least, it certainly seemed to be. Many in India naturally held out hope for its rediscovery, a prospect made all the more exciting by the tercentenary celebrations of Shivaji’s birth in 1927.Footnote 85 Mindful, perhaps, that fascination with Shivaji was reaching a fever pitch and that the public’s appetite for the sword was not yet satiated, a Parsi businessman issued a self-published pamphlet in 1929 proclaiming an important discovery. The Bhavani Talvar, Bomonjee Pudumjee claimed, was not in London because it had never left India. It was not in Satara Fort, moreover, nor in Benares, but in his own collection. We have already encountered Pudumjee in the context of his remarks on the sword in Satara, remarks that were undoubtedly aimed at bolstering the case for his own specimen. But before considering the details of his argument, we should pause to consider the man himself.

The various commercial ventures of the Pudumjee family—including an ice factory, a bank, and a paper mill that still operates in Pune today—are well known.Footnote 86 Our Pudumjee maintained a connection to the ice factory but in general sought to make his mark outside the family business.Footnote 87 In 1901, he was serving as bullion keeper, or cashier, of the imperial mint in Bombay and had received a patent for a lamp used in moving vehicles.Footnote 88 Scattered references to large charitable donations, an invitation to a governor’s soirée, and memberships in musical, sports, and historical associations suggest that he rubbed shoulders with the upper echelon of Bombay and Pune society.Footnote 89 His use of the title Khan Bahadur, which he inherited from an ancestor who had received it from the colonial government,Footnote 90 may have enhanced his status in such circles and suggests pride in his family’s contributions to state and society. His interest in history and antiquarianism seems oriented towards similar goals, since his writing represents collecting not as an act of self-indulgence but as one of historical preservation aimed at the public good. Taken together, Pudumjee’s diverse interests and activities reveal a social sphere that valued innovation and civic engagement as markers of the ideal citizen subject. In this respect, the turn in the discourse on Shivaji’s sword towards Pudumjee highlights the burgeoning role for such individuals in conversations about Indian history and even in shaping the legacy of one of its most enduring icons (see Figures 5 and 6).Footnote 91

Figure 5. Cover of Bomonjee D. Pudumjee, Notes on the subject of Shivaji’s sword (Bombay: Charni Road, 1929). Source: Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA, United States.

Figure 6. Low-quality photograph of the sword acquired by Bomonjee D. Pudumjee, in Pudumjee, Notes on the subject of Shivaji’s sword, p. 3. Source: Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA, United States.

Pudumjee claimed to have acquired his prized object at an auction in Pune in an unspecified year, without any knowledge of its original owner, and to have sent it for restoration to an Indian arms expert in Bombay in 1912.Footnote 92 In cleaning the blade, the expert, M. D. Moos, discovered a Devanagari inscription inlaid in gold: chatrapati mahārājā śīvājī [sic]. There are several reasons to doubt this fairy tale-like account, namely, the peculiar letter that Moos supposedly wrote to Pudumjee (and that Pudumjee in turn reproduced in his pamphlet) in which Moos matter-of-factly informs his client that his item is both ready for pick-up and the former property of Shivaji the Great. Its odd tone notwithstanding, the letter carries the authority of its author—who was at the time of the pamphlet’s publication known for his consulting work for the Wallace Collection in London—and is thus a clear attempt to capture his opinion in writing.Footnote 93 Even so, the likelihood that the letter is staged does not render its narrative impossible nor, certainly, its opinion inauthentic. And its description of the engraving does indeed suggest that the markings may have been centuries-old, or at any rate much older than the recent fascination with Shivaji that might have inspired a more unscrupulous collector to add them to the blade.Footnote 94

A closer examination of this engraving nevertheless exposes problems for Pudumjee. We might note, first, that the initial vowel in ‘Shivaji’ is long—rendering Śīvājī as opposed to the standard Śivājī—a quirk that on its own would be easy to excuse as a variant or error. But reflecting on this irregularity leads us to consider a more serious issue in the inscription: the reference to Shivaji as chatrapati. That Shivaji adopted this title is not in dispute, but—as Pudumjee’s contemporary V. S. Bendrey would emphasize in his analysis of Pudumjee’s claims—he only did so after he was crowned in 1674, six years before his death.Footnote 95 That Shivaji might have added the inscription after that date does not strike me as implausible, and it is interesting that Bendrey does not so much as entertain the possibility. More interesting still is that he does not consider that Shivaji might have acquired the sword during or after his coronation, which on its own would be enough to prove that it is not the legendary Bhavani Talvar. Perhaps Bendrey does not want to entertain the existence of another of Shivaji’s swords or perhaps the thought simply does not occur to him; either way, we have further evidence that a discourse around a single surviving sword, the Bhavani Talvar, was solidifying.

Just as the engraving that Pudumjee regards as his smoking gun actually exposes some of the sword’s deficiencies, so, too, do the symbols on the opposite side of the blade to which he draws special attention. In interpreting these as the phases of the moon (‘marks of the whole, ¾ and half circles’),Footnote 96 Pudumjee may be correct in noting that they allude to verses on Shivaji’s seal,Footnote 97 but this need not imply, as Pudumjee insists that it does, that ‘the sword cannot but be Shivaji’s’.Footnote 98 Not only were later Maratha figures eager to evoke their heroic forebear, but lunar imagery enjoyed a wide resonance across early modern India (and beyond). Alas, if we adopt Pudumjee’s own ‘process of exclusion’—by which he questions the authenticity of rival swords to single out the Bhavani TalvarFootnote 99—then the case for his own is no stronger than those he rejects.

Again, my goal is not to debunk the identification of an object I have not seen. What I want to show, rather, is how Pudumjee’s defence of his sword—and, especially, his ability to force the public to contend with that defence—illustrates the new kinds of engagement with the past that were emerging in the colonial public sphere. I am thinking here of Dipesh Chakrabarty’s notion of the ‘cloistered’ and ‘public’ lives of history in early twentieth-century India, albeit in a slightly different manner from how he employs these terms. Like him, I am interested in how ‘discussions in the public domain actually come to shape the fundamental categories and practices of the discipline’s “cloistered” or academic life’.Footnote 100 But whereas Chakrabarty’s focus is on the public discussions of career historians, mine lies nearer the margins, where an educated, engaged, but decidedly lay historian aspired to engage in, and even reorient, a major historical discussion. Admittedly, Pudumjee’s interest in these discussions reflected not only historical interest but also, and perhaps especially, his business acumen. That he chose to enclose a copy of his Notes on the Subject of Shivaji’s Sword in his letter to the noted Sanskritist W. Norman Brown, for instance, was presumably to encourage Brown to read on about his ‘very valuable oil painting of Shivaji’ and ‘a superb collection of old China’ that he hoped to sell to Brown or his acquaintances (see Figures 7–8).Footnote 101 The public life of history was thus for Pudumjee at once a domain to which engaged citizens such as himself were expected to aspire and a platform from which he could forward his business interests. Either way, his sword was his ticket in.

Figures 7–8. Letter from Bomonjee D. Pudumjee to W. Norman Brown, 24 November 1928, Bombay. Source: Kislak Center for Special Collections, Misc. Mss Box 2, Folder 41, the University of Pennsylvania, United States.

By entering the discourse around Shivaji, Pudumjee not only participated in one of the most animated historical dialogues of his time but also exposes directions they might have taken. The colonial state had grown increasingly weary of Shivaji by the end of the 1920s, associating his admirers with communalism and the Hindu Right. That Pudumjee, a Parsi whose allegiance to the colonial state was clear, believed he could mould Shivaji’s legacy—or, at a less lofty level, simply benefit from it—suggests that the public discourse around Shivaji was still open to interpretation and negotiation. Moreover, in staking his claim to the Bhavani Talvar in particular, Pudumjee emerges as not just another voice in discussions, for if (as all parties seemed to agree) the transference of Shivaji’s sword marked the transference of Shivaji’s authority—whether to the raja of Kolhapur, the maharaja of Satara, or even the Prince of Wales—then that authority now seemed to reside quite literally in the hands of a public citizen.

Or did it? Reflecting on Pudumjee’s sword some 50 years later, a journalist for the Nagpur Times rather cuttingly remarked that it ‘was never accepted by anybody as the real Bhawani’.Footnote 102 This characterization is a bit unfair, since Pudumjee’s case was built on the statements of what he considered a dream team of antiquarians and Maratha history experts.Footnote 103 Additionally, his claims garnered enough attention to prompt curators of the British Museum to consider (and, admittedly, reject) them.Footnote 104 But the journalist has a point insofar as Pudumjee’s sword never captured the popular imagination in the manner of its rivals. Ultimately, Pudumjee would sell his beloved sword, which in time found its way to another enthusiastic owner who penned a pamphlet of his own.Footnote 105 The sword and the second volume on it have since languished in obscurity.Footnote 106

Pudumjee’s case thus illustrates an important contradiction. It at once reveals the ease with which citizens could stake plausible claims to Shivaji’s legacy within the public sphere and the reticence of the public to accept them. We must remember that although the provenance Pudumjee supposed for his sword now appears doubtful, it did not necessarily seem that way at the time; indeed, his failure to persuade the public cannot be attributed to any dearth of expert opinions nor, surely, to the doubts expressed by the curators of the British Museum, whose disavowal of the Kolhapur sword in its collection did nothing to blunt the enthusiasm of the public. Pudumjee’s failure, though it was assuredly disappointing for him, is thus eminently useful for us, offering as it does an example of how the democratization of Shivaji that was then developing was also becoming circumscribed. I see this in at least two important respects. First, the notion that Shivaji was a shared historical and national treasure may have been growing, but his legacy could not attach to just anyone, even if that someone could make a decent case that he possessed the legendary sword. Rather, that legacy—together with the sword that represented it—had to attach to someone connected to the familiar narratives around Shivaji’s legacy; these figures were typically royal—especially Shivaji’s descendants or the British royal family—or, as Antulay and Modi demonstrate in the post-colonial context, political. Second, and more important for our purposes, is that there was the emerging sense that Shivaji’s vision had been—and would for some time continue to be—unrealized. For this critical element in Shivaji’s mythos to be preserved, his sword, which served as the physical manifestation of that mythos, had likewise to be just out of reach.

Three hundred years a king: A Satara interlude

For many in India, it was London that seemed just out of reach. Decades of denials by British officials had done little to quash the idea that Shivaji’s sword might still be in the city; such tenacity owed much to the appeal of the narrative, for decidedly more alluring than the prospect of Shivaji’s sword appearing at a Pune auction was that it had been whisked away to the nation that had dashed Shivaji’s dreams of a united, sovereign India.Footnote 107 At the same time, the fixation with London was no mere flight of fancy. Whispers that the sword brought back by Albert Edward remained there continued, appearing most prominently in a 1927 Marathi article by Gajanan Manikrao, who mentions ‘the Shri Bhavani placed in a golden cupboard in Buckingham Palace’.Footnote 108 Although he does not include sources, it seems that Manikrao had access to (or at least knowledge of) an 1898 catalogue of objects ‘in the Indian Room at Marlborough House’.Footnote 109 Like the collections itself, this catalogue does not appear to have been accessible to the public, thus explaining why even a well-placed civil servant and historian like S. M. Edwardes (whom we left having exhausted leads in London) apparently had no knowledge of it. Marlborough House had been Albert Edward’s primary residence while Prince of Wales, and the catalogue makes clear that it was here, and not in the British Museum, that many objects he had collected in India ‘were definitively installed’ sometime after their public exhibition ceased in 1881.Footnote 110 Together with a description, the text includes an early photograph of the sword, which rests with its scabbard in a display case among other Indian arms (see Figure 9).Footnote 111 Whether Manikrao conflated Marlborough House with nearby Buckingham Palace or whether he presumed that Albert Edward took the sword there with him upon his accension in 1901 remains unclear.Footnote 112

Figure 9. Photograph from the Catalogue of the collection of Indian arms and objects of art presented by the princes and nobles of India to H.R.H. the Prince of Wales … on the occasion of his visit to India in 1875–1876 …, Case J. Source: © British Library Board, General Reference Collection K.T.C.41.b.18. Asia, Pacific and Africa X 408.

The prominence of Manikrao’s article appears to have done much to reorient the search away from the British Museum and towards Buckingham Palace. So intense was public interest in the new location that the Maratha historian V. S. Bendrey somewhat begrudgingly agreed to investigate the rumours during a research stint in London in 1937. Though he characterized the association between Shivaji and ‘a sword in Buckingham Palace’ as ‘nothing but unverified tradition’,Footnote 113 he nevertheless issued a formal viewing request to the royal comptroller. The comptroller confirmed the existence of such a weapon, bringing the whereabouts of the Kolhapur sword fully into the public eye for the first time in decades. But in doing so, he described an almost comically unattainable object, which hung in the inner chambers of a royal residence (it is not clear which) ‘in a special anti-burglar electric alarm case’.Footnote 114 Frustrating though this arrangement undoubtedly was for the historian, it only enhanced the sword’s mythical status among the public, satiating a need to locate the sword without actually attaining it and thereby spoiling the chase.

And, indeed, the chase continued, even after independence. By 1971, the sword was, for the first time, visited by a high-ranking Indian official, the high commissioner to the United Kingdom. ‘The moment I set eyes on it I felt deeply impressed by and attracted towards it,’ the commissioner, Apa Pant, would later recall. ‘It has some kind of great power which one feels immediately.’Footnote 115 Such remarks are not unexpected from Pant, who was a scion of a Maratha vassal state and, despite forging a career in the minutiae of diplomacy and bureaucracy, of a strong mystical and philosophical bent.Footnote 116 Even so, his words are representative of the intense feelings that the broader Indian public now had towards the sword, which (and in this respect Pant’s visit was the exception) remained inaccessible. The following year, Kashiram Sawant Desai—the name ‘Sawant’ signalling his descent from the same clan that had supposedly first given Shivaji the sword—embarked on a less successful campaign to secure ‘unrestricted permission to reproduce photographs of the Sword of the Shivaji the Great’. The response to his formal request comprised little more than a snide letter and red tape.Footnote 117

It was at this time, when all eyes were fixed on London, that they reverted, rather suddenly, back to India. In much the same way that the tricentenary of Shivaji’s birth had heightened the public’s attachment to him in 1927, the 300th anniversary of his coronation stoked new interest in his legacy in 1974.Footnote 118 This was no insignificant milestone: in adopting the title chatrapati in 1674, Shivaji had, his supporters claimed, revived a tradition of ancient Hindu kingship that centuries of Muslim rule had obfuscated. The epicentre of festivities was Bombay, whose Shivaji Park—acquiring that name, appropriately, during the celebrations in 1927—featured an elaborate exhibition celebrating his life. Attendees included a who’s who of Hindu nationalism, including the Shiv Sena founder Bal Thackeray, who held a rally at the foot of the park’s Shivaji statue.Footnote 119 But the real star was not an individual. The sword from Satara, which had played a peripheral part in the discourse around Shivaji’s sword for over a century, now, for the first time in its recorded history, left Satara Fort and came to Bombay. It arrived in style: amid shouts of ‘Shivaji Maharaj ki jai!’ (Long live Maharaja Shivaji!), a truck designed to look like a royal elephant approached Shivaji Park, bearing the sword and flanked by men dressed in traditional Maratha battle attire (see Figure 10).Footnote 120 Though the exhibition would remain in Shivaji Park for over a month, the sword was on public display for only five days, during which it was visited by about half a million people. It would return to Satara after 45 days of fanfare.Footnote 121

Figure 10. Photograph of Babasaheb Purandare with the Satara sword in S. L. Sharma (ed.), 300th anniversary of coronation [sic] of Chatrapati Shivaji Maharaj souvenir (New Delhi: The Foreign Window Publishing, 1974), p. 15.

The spectacle was over almost as soon as it began. Its ephemeral nature, occupying only a few days of the sword’s centuries-long history, paralleled the transience of the tercentenary itself. Though cultural critics like Walter Benjamin and Karl Marx have interpreted ephemerality as a function of modernity,Footnote 122 we might associate the public display of the Satara sword more specifically with post-coloniality. As the celebrations of 1927 demonstrate, there had been many earlier occasions to parade this sword around Maharashtra, but only now did its sudden arrival (and, I should emphasize, prompt departure) resonate. Following a decade in which ephemerality was, according to Reiko Tomii, a ‘defining issue’, the appearance of the sword spoke to the tantalizing proximity of Shivaji’s legacy.Footnote 123 To his admirers on the Hindu Right, it seemed his dream of an independent India had been achieved but its contours not yet fully realized—an anxiety that the sword’s fleeting presence could approximate. When it was returned to Satara, however, the mirage of Shivaji’s dream no longer attached to a stationary and accessible object. The ever-elusive vision of Shivaji’s India needed an ever-elusive sword, and so the public’s attention turned once again to London.

Some had never looked away. In April 1980, Kashiram Desai was continuing the fight he had begun in 1972, though now he had largely passed his standard to his seven-year-old grandson, Amol. Unsatisfied with simple photography rights, Amol Desai upped the ante and requested that the London sword be sent to Maharashtra as a gesture of goodwill during the International Children’s Year. In rejecting the younger Desai’s request, the Surveyor of the Queen’s Works of Art offered what he hoped was a nugget of good news: ‘I am, however, commanded to send you photographs of the sword which I hope will convey to you an idea of its quality and which at the same time, in the absence of the actual sword, will go some way towards allaying your disappointment.’Footnote 124 The fact that the letter was reprinted in full in an Indian newspaper does not on its own tell us much about the boy’s response; assuming he played a part in delivering the letter to the paper, the act could imply a kind of a public shaming of the surveyor or, conversely, a measure of pride in having received a response at all.Footnote 125 Whatever his intention, Amol was not alone in his efforts, for his was only one of many letters written by Maharashtrian schoolchildren to the Lord Chamberlain’s office around this time.Footnote 126

Interest in the London sword was also heating up in the political sphere. A member of the Legislative Council at Bombay, Manmohan Tripathi, wrote directly to Queen Elizabeth to request its return.Footnote 127 Though his petition was batted down, presumably before the Queen ever saw it, it marks what may be the first attempt by an elected Indian official to regain the sword. All the cause needed now was a more audacious figure with the political wind at his back. It was in this context that A. R. Antulay, the chief minister of Maharashtra whose recent election victory opened this article, made a vow to go to London.

‘Bravo Barrister Antulay’: A sword unsheathed

A political cartoon that ran in Blitz, a Bombay newspaper, painted a predictably satirical image of the indefatigable chief minister (see Figure 11).Footnote 128 Wearing what appears to be a Chitrali topi (a skull cap associated with the Pakhtun regions of Pakistan), Antulay rides a white horse named ‘By-Election Success’. His traditionally Muslim attire is belied by his Hindu battle cry (‘Har Har Mahadeo!’) as well as his sword: the Bhavani Talvar.Footnote 129 Evocative of his rivals’ claim that his cause célèbre was directed at no one in particular, Antulay’s nameless antagonist stands somewhere outside the frame. Looking on in the background, disgruntled and perhaps a bit tired, are two members of the Maratha lobby. ‘Is the sword genuine or not … ?’ asks one. ‘Forget that!’ replies the other, ‘My grief is how we couldn’t think of this gimmick!’ [emphasis in original]. Gyan Prakash has identified Blitz’s signature as ‘its muckraking, over-the-top stories calculated to provoke and enrage’, a generalization that easily applies to political cartoons like this one.Footnote 130 But beyond poking fun at the political class, this piece and the accompanying article make an important point: that a Muslim politician whom the Maratha lobby ‘had branded … as Afzal Khan’ had become an unlikely crusader for Shivaji, the favourite icon of the Hindu Right.Footnote 131 And his critics knew it.

Figure 11. Political cartoon by Shresh, ‘Mystery of Antulay’s airdash abroad’, Blitz, 13 December 1980. Source: The National Archives, Kew, ref. FCO37/2331.

This was not Antulay’s first attempt to prove his admiration for Shivaji: his earlier efforts included founding something called the Shivaji Maharaj Secular Aspect Committee and renaming Maharashtra’s Colaba district ‘Raigad’ after Shivaji’s eponymous fort.Footnote 132 Though his shotgun journey to London was simply another attempt to use Shivaji to his political advantage, the opposition he now faced was unprecedented. His Muslimness was a particular target for some, including Sharad Pawar, the previous chief minister of Maharashtra, who accused Antulay of wanting to appear secular ahead of the pilgrimage he had promised to make to Mecca after his electoral victory.Footnote 133 Others emphasized the sheer opportunism of it all, including Narayan Ganesh Gore, a prominent socialist leader and a former high commissioner to the United Kingdom, who quipped that, ‘Even Mr. Antulay should realise that there is a limit to the common man’s gullibility.’Footnote 134

Cutting across and reinforcing such criticisms was the matter of timing, since Antulay’s trip coincided not only with his pilgrimage and the recent election but also with the journey of another prominent individual headed the other way. For as Antulay sat down to make his case before London authorities, Charles, Prince of Wales, was touring Bombay. Antulay’s political opponents charged that the chief minister’s ‘very untimely visit’ proved that he was not serious about returning the sword, a goal that he might actually have drawn nearer had he stayed in Bombay to welcome the man who would inherit it.Footnote 135 Antulay attempted to turn these accusations on their head during his audience with British officials, noting, as paraphrased in the minutes, that ‘it was perhaps appropriate that while the Prince of Wales was in Bombay, he should be in London making representations for [the sword’s] return’.Footnote 136

British officials, for their part, adopted a double-pronged approach in the meeting. Their first tack was to repeat doubts about the sword’s authenticity. At the same time, the Minister of Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, Peter Blaker, maintained that there was simply no precedent for returning a royal gift. Antulay coolly retorted that Indo-British relations had seen many events without precedent, including independence.Footnote 137 Despite the occasional zinger, however, Antulay’s tone with British officials was more subdued than the one he used with the Indian press. He apparently accepted ‘that the sword was H[er] M[ajesty]’s personal property’, even as he ‘hoped that she could be persuaded to return it’.Footnote 138 Blaker and the Lord Chamberlain assured Antulay that they would take up the matter with the Queen but noted that he would still need to make his request through formal channels. The entire meeting—including briefer discussions of more conventional matters—lasted less than half an hour.Footnote 139

Returning to India empty-handed, Antulay insisted that he had never intended to secure the sword’s return during what he now (not entirely truthfully) referred to as an ‘exploratory’ trip.Footnote 140 The media pilloried him for what it perceived as a failure even as it underscored doubts about the sword, publishing a unanimous declaration from the politically influential Bharat Itihas Samshodhan Mandal that it was not the Bhavani Talvar, while also resurrecting a statement on the topic from Govind Sakharam Sardesai, who—though he had died two decades earlier—remained a respected voice in historical circles and the wider public sphere.Footnote 141 Cornered by these criticisms, Antulay finally admitted that he could not prove that the sword was the Bhavani Talvar. But he emphatically maintained that it was Shivaji’s. In a characteristic pivot, he insisted that the only way to determine definitively whether it was the Bhavani Talvar was to bring it back to India.Footnote 142

Antulay had wobbled before reporters and historians, going so far as to consider, if only briefly, the existence of multiple surviving swords. His political critics, who, as we have seen, included socialists and members of both the left-of-centre Congress (U) Party and right-of-centre Janata Party,Footnote 143 were likewise unimpressed by his antics in London. Mindful, perhaps, that these groups had formed a hodgepodge alliance with the journalists and experts eager to debunk Antulay’s claims, Antulay and his supporters sought to make their arguments outside and even in deliberate opposition to these spaces.Footnote 144 British experts offered particularly useful fodder: when a parliamentary session descended into squabbling after a Congress (U) member cast doubt on the sword’s authenticity, likening the object to a ‘political slogan’, a member of Antulay’s own Congress (I) Party lambasted his colleague for daring ‘to give a controversial touch to the matter on the basis of reports of curators of Albert [sic] or Buckingham Palace museums’.Footnote 145

Although these defensive remarks did not meaningfully dent the vigorous opposition he now faced, Antulay surely took heart knowing that his rivals were only energized because his cause was widely popular. Indeed, in reaching the public, even his sharpest critics conceded, he had played a shrewd political game. P. V. Ranade, a professor of history at Marathwada University, in a column dripping with sarcasm, imagined what Antulay might tell his constituents next:

If Antulay engages some enterprising historian to dig up the modern archives, he is sure to come across a prophecy made by Lokmanya Tilak in 1908 that the next incarnation of Shivaji will take place in a Muslim family … . A still more enterprising historian from Maharashtra would confirm that Lokmanya Tilak had Antulay in his view when he made this prophecy while delivering his address on the occasion of the Shivaji Festival in Calcutta in 1908.

Bravo Barister Antulay [sic].Footnote 146

Ranade, who in 1974 had briefly lost his teaching position after writing an article deemed critical of Shivaji,Footnote 147 understood the emotions that the figure could instil. The Maharashtra Times made this point more explicitly: ‘When it comes to Shivaji Maharaj the moment anyone starts to say or write anything about him, Maharashtrians lose their senses and it does not occur to anyone to check what is being said.’Footnote 148 While Ranade and The Maharashtra Times were correct insofar as Shivaji could and did produce strong reactions, the case of Pudumjee demonstrates that even Shivaji’s sword was not a sure-fire way to capture the public’s attention. What, then, made Antulay’s cause resonate?

The success of his narrative owes much to the fact that what critics saw as two of its biggest flaws proved in the end to be its greatest hooks. The first was the insistence by British officials and Indian academics and journalists that the sword in London was European, and specifically Portuguese, a claim based on the inscription ‘I.H.S.’ stamped three times in a groove on its blade. Most Indian commentators correctly took these letters to denote ‘Iesus Hominum Salvator’ (Jesus, Saviour of Humanity), a popular Christogram associated with the Franciscan order. Though some made erroneous readings, including Antulay himself,Footnote 149 they usually arrived at the same conclusion: that the sword was probably of Catholic provenance and Goa—a Portuguese colony with a strong Franciscan tradition—was its most likely place of origin.Footnote 150 For British authorities, a European manufacture and even a European inscription were not inconsistent with accepted knowledge about Indian swords, but the distinctly Christological significance of the markings gave them pause.Footnote 151 Blaker had made this a central talking point during his conversation with Antulay: he argued that the sword ‘was in fact of a date later than the 17th Century, and it bore Christian monograms’. I. D. Singh, an Indian weapons expert accompanying Antulay, correctly noted that ‘there was a long history of Christianity in India, going back well before the 17th century’, but in doing so he seems to have missed Blaker’s point.Footnote 152 His contention was not that it was more recent because it bore Christian insignia, but that it was both more recent and bore Christian insignia, two claims, Blaker believed, that together proved that a Hindu ruler from the seventeenth century could not have a Christian sword from a later century.Footnote 153 Confusion regarding Antulay and Singh’s acceptance, even embrace, of the sword’s Christian markings continued in Whitehall until a second demand for the sword arrived from an Indian MP. In reviewing the request, a certain Mr Bhalla advised the British government not to mention the insignia in its response, noting that it would substantiate the narrative that Shivaji had acquired the sword from the Sawant family who had won it from the Portuguese. ‘[A] Christian monogram might go some way in confirming its authenticity, rather than the converse,’ he explained.Footnote 154

The second obstacle-turned-boon for Antulay was that it had been only six years since Maharashtra had celebrated the journey of the Bhavani Talvar from Satara to Bombay. Sharad Pawar drew particular attention to this point: ‘The real Bhavani Sword was accepted by me in the presence of Bal Thackeray in 1974 on behalf of the State Government. How could I subscribe to Antulay’s theory that there is yet another Bhavani Sword?’Footnote 155 Curiously, Pawar was one of the few individuals prominently featured in those events to come out publicly against Antulay’s crusade. Sumitraraje Bhosle, the Rajmata (queen mother) of Satara and a powerful figure in Maharashtrian politics, presumably had many reasons to defend the exclusivity of her family’s most cherished heirloom; instead, she was receptive to the idea that there might be another sword, so much so, according to Antulay, that she offered to go with him to London to collect it when and if the Queen agreed. (‘This only shows what the Rajmata feels about [the matter],’ he told the press.)Footnote 156 The public historian and writer Babasaheb Purandare, whose historical fiction involving Shivaji has played a key role in shaping his legacy in contemporary Maharashtra, offers a similarly peculiar case. Though he had been the chief architect of the exhibition of the Satara sword in Shivaji Park in 1974, he remained, as The Indian Express put it, ‘tight-lipped over the controversy’ in 1980.Footnote 157

The receptiveness of figures like the Rajmata to the authenticity of the London sword, together with the public’s eager acceptance of its European origins, helps bring critical aspects of the object’s appeal into sharper relief. Presumably the Rajmata and Purandare, whatever their private feelings, chose not to challenge the sword’s legitimacy because it encouraged interest in Shivaji’s legacy, which in turn bolstered their own aims.Footnote 158 The sword’s European connections were part of this same discourse. Though Bhalla was correct that a Portuguese origin had significance for those steeped in the sword’s lore, we must recall that the story involving the Sawants was not widely known; the blade’s purported Portuguese manufacture, then, must have offered the public something more than evidence of a lesser-known historical claim. And in this regard its specifically Portuguese origin appears critical. Naturally the Satara blade, too, has been linked to Europe in the earliest attestations we have about it, but the value there seems to lie in the craftsmanship. Simply put, it appears that Genoa, or even a generically European origin, could not wield the same political charge as Portugal, the first colonial power to establish a foothold in the subcontinent. I want to suggest, then, that the importance of the sword being made and marked by European imperialists runs parallel to, and is mutually reinforcing with, the importance of its being taken away by them. We have already seen how the image of Shivaji’s sword held in the colonizers’ capital encapsulated both the potential and the loss of Shivaji’s vision, giving the object a narrative advantage over its counterpart in Satara through the promise of its eventual return. The idea that the sword’s origins also lay with colonizers bolsters this narrative by affixing to it the reminder that the object was won from a colonial power once before. All that was required now was a leader, or, better yet, a nation, powerful enough to repeat the act.

Epilogue: The stuff that dreams are made of

Reflecting on his meeting with British officials in London, Antulay told the Indian press that the Lord Chamberlain had asked him why the people of Maharashtra had awakened ‘“so suddenly” to demand the return of the sword’.Footnote 159 He said he had assured the Lord Chamberlain that his position was nothing new and cited a 1918 poem calling for its return. Written by the Marathi literary giant Ram Ganesh Gadkari on the occasion of Tilak’s journey to London, the poem considers what the nationalist leader should demand in the metropole: