Long-acting injectable (LAI) formulations of antipsychotics are valuable treatment alternatives to oral agents, offering continuous medication delivery and favourable dosing intervals. Evidence suggests that many patients accept and may even prefer LAI administration.Reference Heres, Schmitz, Leucht and Pajonk1,Reference Patel, De Zoysa, Bernadt and David2 Aripiprazole once-monthly is an LAI formulation of aripiprazole that is currently approved in the USA and Europe for the treatment of schizophrenia, and is the first dopamine partial agonist agent available in a long-acting formulation. Aripiprazole once-monthly is administered by gluteal injection and once injected, the active ingredient, aripiprazole, is slowly absorbed into the systemic circulation; there is no release vehicle or release-controlling membrane. In a previous study, aripiprazole once-monthly significantly delayed time to impending relapse compared with placebo.Reference Kane, Sanchez, Perry, Jin, Johnson and Forbes3 Aripiprazole, a dopamine partial agonist,Reference Burris, Molski, Xu, Ryan, Tottori and Kikuchi4 is an antipsychotic with well-established efficacy and safety over the short and long term.Reference Croxtall5 For LAI formulations, a study comparing the efficacy and safety v. the oral form is recommended to support authorisation by the European Medicines Agency (EMA)Reference Kane, Sanchez, Perry, Jin, Johnson and Forbes3 and to demonstrate efficacy, safety and tolerability similar to the established profile of the approved oral product. The objective of the present randomised, double-blind, active-controlled, non-inferiority study was to assess the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of aripiprazole once-monthly (400 mg) for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia compared with oral aripiprazole and in comparison with a suboptimal dose of aripiprazole once-monthly (50 mg). A suboptimal dose was included to confirm assay sensitivity (i.e. to demonstrate that the study was able to differentiate an effective treatment from a less effective or ineffective intervention by demonstrating superior efficacy).

Method

Study design

This was a 38-week, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, active-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy, safety and tolerability of an intramuscular depot formulation of aripiprazole (OPC-14597) as maintenance treatment in patients with schizophrenia (ASPIRE EU: Aripiprazole intramuscular depot program in schizophrenia, trial registration: clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00706654). The study consisted of a screening phase and three treatment phases (phases 1-3). Eligibility was determined during the screening phase (2-42 days). In treatment phase 1 (oral conversion phase, 4-6 weeks), patients were cross-titrated during weekly visits from other antipsychotic(s) to oral aripiprazole monotherapy to achieve a target dose of 10-15 mg/day. Patients receiving oral aripiprazole monotherapy for schizophrenia at screening entered the study directly at phase 2.

In phase 2 (oral stabilisation phase, 8-28 weeks), patients were assessed fortnightly and stabilised on oral aripiprazole (10-30 mg/day). Stability was defined as meeting the following criteria for 8 consecutive weeks: out-patient status; Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler6 total score ⩽80 and a score of ⩽4 (moderate) on each of the following items (possible scores of 1-7 for each item): conceptual disorganisation, suspiciousness, hallucinatory behaviour, and unusual thought content; Clinical Global Impression - Severity (CGI-S) score ⩽4 (moderately ill);Reference Guy7 and Clinical Global Impression - Severity of Suicidality (CGI-SS) score ⩽2 (mildly suicidal) on Part 1 and ⩽5 (minimally worsened) on Part 2. The definition of stability was approved by the EMA and was similar to other stability definitions used in previous studies of approved LAIs for the treatment of schizophrenia.Reference Hough, Gopal, Vijapurkar, Lim, Morozova and Eerdekens8

In phase 3 (double-blind maintenance phase for up to 38 weeks), eligible patients were randomised 2:2:1 to aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg, oral aripiprazole (10-30 mg/day) or aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg. Aripiprazole once-monthly was administered into the gluteal muscle using a double-dummy design such that all patients, including those randomised to oral aripiprazole, received an injection. For patients randomised to aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg or 50 mg, a one-time option to decrease to 300 mg or 25 mg, respectively, was permitted, as was a one-time return to the original assigned dose. Patients treated with aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg or 50 mg received concomitant oral aripiprazole (10-20 mg) for 2 weeks from the date of randomisation, and then placebo tablets thereafter. This dosing strategy was based on previous pharmacokinetic studies that demonstrated that 400 and 300 mg aripiprazole once-monthly exhibited pharmacokinetic and safety profiles similar to those of multiple, consecutive, daily oral doses of 10-30 mg aripiprazole monotherapy.Reference Mallikaarjun, Kane, Bricmont, McQuade, Carson and Sanchez9 For patients randomised to oral aripiprazole, a one-time change in dose (increase or decrease) and a one-time reversal of the change (decrease in dose if previously increased or increase in dose if previously decreased) was permitted as long as the dose remained within the range of 10-30 mg daily.

The study was conducted at 105 centres in Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Chile, Croatia, Estonia, France, Hungary, Italy, South Korea, Poland, South Africa, Thailand and the USA between 26 September 2008 and 31 August 2012. In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the ethics committee at each site approved the protocol. After complete description of the study to patients, written informed consent was obtained.

Patients

Eligible patients were aged 18-60 years and had a diagnosis of schizophrenia according to DSM-IV-TR10 criteria for ⩾3 years and a history of symptom exacerbation when not receiving antipsychotic treatment. Patients needed to have been responsive to antipsychotic treatment (other than clozapine) in the past year. Key exclusion criteria included a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis other than schizophrenia; uncontrolled thyroid function abnormalities; a history of seizures, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, clinically relevant tardive dyskinesia, or other medical condition that would expose the patient to undue risk or interfere with study assessments. Patients who had been admitted to hospital, including for psychosocial reasons, for >30 days total of the 90 days preceding entry into phase 1 or 2 of the study after screening were excluded. Individuals were also excluded if they met DSM-IV-TR criteria for substance dependence, including alcohol and benzodiazepines but excluding nicotine and caffeine. Additional exclusion criteria are noted in online supplement DS1.

Assessments

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the Kaplan-Meier estimated impending relapse rate from the date of randomisation to the end of week 26. Patients were assessed for impending relapse, defined as meeting any one or more of the following specified individual criteria at any time during phase 3:

(a) CGI - Improvement (CGI-I) of ⩾5 (minimally worse) and either an increase on any of four individual PANSS items (conceptual disorganisation, hallucinatory behaviour, suspiciousness or unusual thought content) to a score >4 with an absolute increase of ⩾2 on that specific item since randomisation, or an increase to >4 on one of those PANSS items and an absolute increase of ⩾4 on the combined score of those items;

(b) admission to hospital as a result of worsening of psychotic symptoms;

(c) CGI-SS score of 4 (severely suicidal) or 5 (attempted suicide) on Part 1 and/or of 6 (much worse) or 7 (very much worse) on Part 2; and

(d) violent behaviour resulting in clinically relevant self-injury, injury to another person or property damage.

Secondary efficacy outcomes

Time to observed impending relapse and observed rate of impending relapse at week 38. Secondary efficacy assessments included time to observed impending relapse (time to earliest date that the patient met ⩾1 of the impending relapse criteria (criteria defined above in the section on Primary outcome)) from randomisation to study end-point (week 38). Observed impending relapse rate at study end-point (week 38) was also compared. Assessments included only those patients who met impending relapse criteria and were calculated as the earliest date the patient met ⩾1 of the impending relapse criteria minus the randomised date plus 1. Hazard ratios were used to evaluate the risk of observed impending relapse (see Statistical analyses section).

Responders and remitters. Other secondary efficacy assessments included the percentage of responders (i.e. meeting stability criteria (see Study design)) at the last study visit and the percentage of patients achieving remission according to predefined criteriaReference Andreasen, Carpenter, Kane, Lasser, Marder and Weinberger11 (i.e. a score of ⩽3 on each of eight specific PANSS items, maintained for a period of 6 months: delusions (P1); unusual thought content (G9); hallucinatory behaviour (P3); conceptual disorganisation (P2); mannerisms/posturing (G5); blunted affect (N1); social withdrawal (N4); and lack of spontaneity (N6)).

Other efficacy outcomes

Additional efficacy outcomes included time to all-cause discontinuation following randomisation; mean change from baseline (defined as the last visit with available data prior to randomisation) in PANSS total scoresReference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler6 and CGI-S; and mean CGI-I score at end-point.Reference Guy7

Safety outcomes

Adverse events were examined by frequency, severity, seriousness and according to whether they resulted in discontinuation from the trial. The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events related to extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) were summarised by the following event categories: akathisia, dyskinetic, dystonic, Parkinsonism and residual. The following scales were also used to assess EPS: Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS),Reference Guy7 Simpson-Angus Scale (SAS),Reference Simpson and Angus12 and Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (BARS).Reference Barnes13 The CGI-SS scale and the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) were used to assess the risk of suicide events during the study.Reference Posner, Brent, Lucas, Gould, Stanley and Brown14 Intensity of injection pain was assessed by patients using a visual analogue scale (VAS; 0 mm, no pain to 100 mm, unbearably painfulReference Jensen, Chen and Brugger15) and assessed by investigators in domains of pain, swelling, redness and induration.Reference Kane, Eerdekens, Lindenmayer, Keith, Lesem and Karcher16 The incidence of clinically relevant changes was calculated for vital signs and routine laboratory tests. Mean change from baseline and incidence of clinically relevant changes were calculated for electrocardiogram (ECG) parameters, prolactin concentration and body weight.

Statistical analyses

The intent-to-treat (ITT) sample included all patients randomised to the double-blind treatment. The efficacy sample included all patients who received at least one dose of treatment and had at least one efficacy outcome assessment in the double-blind, active-controlled phase. The safety sample included all patients who were randomised to double-blind treatment and received at least one dose of treatment in the double-blind, active-controlled phase.

Primary outcome (ITT sample)

The primary efficacy analysis evaluated the non-inferiority of aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg to oral aripiprazole (10-30 mg/day) using the 95% bilateral confidence interval of the difference in estimated impending relapse rate at week 26 (from Kaplan-Meier curve estimates using the ITT population). In order to compute this confidence interval, the proportion of patients with impending relapse for each treatment group was computed using the Kaplan-Meier estimate at day 182, and its standard error was computed using the Greenwood formula. The Kaplan-Meier estimated impending relapse rates at week 26 were calculated as 1 minus the proportions of patients free of impending relapse events. Standard errors were calculated using Greenwood’s formula. The 95% confidence interval of difference in the estimated impending relapse rate between aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg and oral aripiprazole were provided using the pooled standard error with assumption of normality of the estimated difference. A similar methodology was used in computation of the z-statistic for comparison of aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg with aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg in the estimated impending relapse rate at week 26.

Secondary efficacy outcomes

Time to observed impending relapse and observed rate of impending relapse at week 38 (ITT sample). Time to observed impending relapse (based on all available relapse data through week 38) for aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg, oral aripiprazole and aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg was compared using the log-rank test. The observed impending relapse rates were compared between groups using the chi-squared test. Hazard ratios (and two-sided 95% confidence interval for aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg v. oral aripiprazole and aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg, and for oral aripiprazole v. aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg) for risk of observed impending relapse were analysed using a Cox proportional hazard model with treatment as the factor.

Responders (ITT sample) and remitters. The proportion of responders at last visit in phase 3 and the proportion of patients achieving remission were analysed using the chi-squared test. Only patients who remained in the trial for at least 6 months were included in the calculation of remission rates.

Other efficacy outcomes

Time to all-cause discontinuation (ITT sample). Kaplan-Meier curves for the time to discontinuation as a result of all causes were plotted and analysed using the log-rank test.

PANSS, CGI-S, and CGI-I (efficacy sample, last observation carried forward and observed cases). Mean changes from baseline in PANSS total score and CGI-S score were analysed by visit using ANCOVA controlling for treatment and baseline value using last observation carried forward (LOCF). Mean CGI-I scores at week 38 were analysed using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel method based on raw mean score statistics using LOCF. Observed cases data are shown in online Table DS1.

Safety outcomes (safety sample, observed cases and LOCF)

Safety outcomes, including changes from baseline in weight, metabolic parameters and EPS scale scores (BARS, AIMS, and SAS) during phase 3 were analysed using descriptive statistics (observed cases) and/or ANCOVA with treatment as a factor and baseline (score at the end of phase 2) as a covariate (LOCF). In this main report, safety outcomes are reported as observed cases; the online Table DS2 contains observed cases results for metabolic parameters; LOCF findings for safety data are reported in online Table DS3, where available.

Sample size

Sample sizes were estimated to achieve approximately 93% power for the primary non-inferiority comparison at P = 0.05 (two-sided) using large sample normal approximations for the distribution of the difference in binomial proportions. It was assumed that 18% of patients would meet the criteria for an impending relapse at or before week 26 in the oral aripiprazole treatment arm. The resulting sample size was projected to be 260 patients per arm for aripiprazole once-monthly and oral aripiprazole therapies. The predefined non-inferiority margin was 11.5%. This margin was based on data from a previous trialReference Pigott, Carson, Saha, Torbeyns, Stock and Ingenito17 that compared relapse rates for oral aripiprazole and placebo showing estimated relapse rates of 37.4% for oral aripiprazole and 60.6% for placebo at week 26, leading to a one-sided 97.5% lower confidence interval of 15%. Given the potential adherence advantage of an LAI formulation, a conservative margin of 11.5% was selected for the current trial. Non-inferiority was demonstrated if the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval was below the predefined margin. If non-inferiority was established, comparison of aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg with aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg was performed by examining the difference between the estimated impending relapse rates using z-statistics for statistical significance at the 0.05 significance level (two-sided).

Results

Patient disposition and characteristics

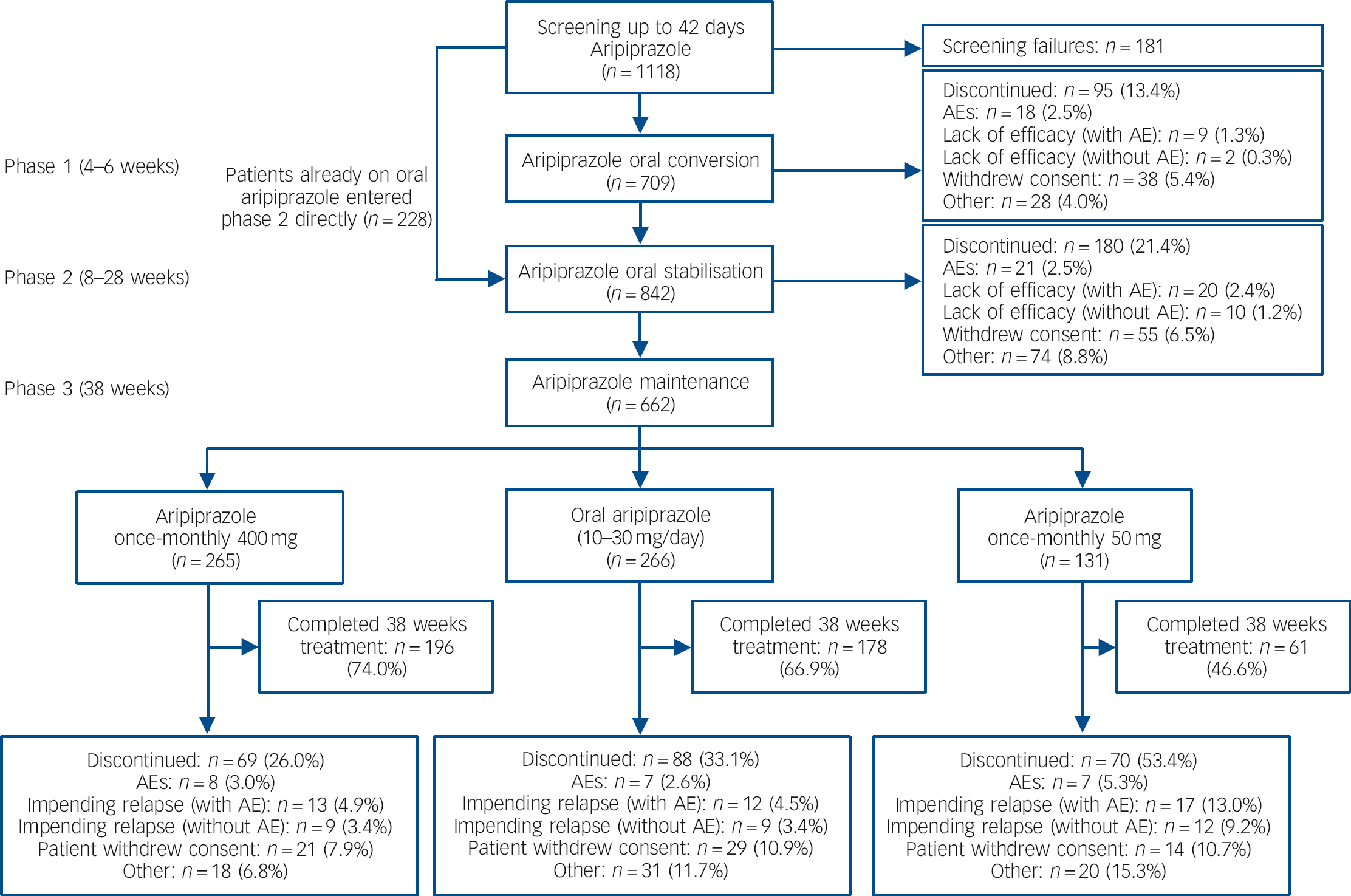

Of 1118 patients screened, 709 patients entered the oral conversion phase (phase 1) and 842 entered the oral stabilisation phase (phase 2), including 228 patients who were already receiving oral aripiprazole and entered phase 2 directly (Fig. 1). A total of 662 patients were randomised to double-blind treatment in phase 3 (Fig. 1). The number of individuals who dropped out because of adverse events was low in the aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg group and oral aripiprazole group; the main reason for discontinuation during phase 3 was patient withdrawal of consent (Fig. 1). For patients receiving aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg, the main reason for discontinuation was impending relapse with an adverse event.

Fig. 1 Patient flow throughout the study. AE, adverse event.

The ITT sample, efficacy sample, and safety sample each comprised a total of 662 patients, including 265 in the aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg group, 266 in the oral aripiprazole group, and 131 in aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg group. Baseline demographic and psychiatric characteristics were similar between treatment groups in the randomised population (Table 1). Treatment exposure data are presented in online supplement DS1.

Table 1 Baseline (at randomisation) demographic and psychiatric characteristics for patients entering the randomised phase of the study

| Aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg (n = 265) | Oral aripiprazole 10-30 mg (n = 266) | Aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg (n = 131) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 41.7 (10.4) | 41.2 (10.8) | 40.2 (9.6) |

| Gender, male: n (%) | 160 (60.4) | 168 (63.2) | 78 (59.5) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 160 (60.4) | 153 (57.5) | 74 (56.5) |

| Black or African American | 56 (21.1) | 64 (24.1) | 33 (25.2) |

| Asian | 29 (10.9) | 26 (9.8) | 14 (10.7) |

| Other | 20 (7.5) | 23 (8.6) | 10 (7.6) |

| Weight, kg: mean (s.d.) | 83.4 (20.9) | 83.7 (19.2) | 82.9 (24.4) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2: mean (s.d.) | 28.9 (6.7) | 28.7 (5.9) | 28.7 (7.9) |

| Age at first diagnosis, years: mean (s.d.) | 28.2 (9.3) | 26.9 (9.1) | 26.3 (7.9) |

| PANSS total score, mean (s.d.) | 58.0 (12.9) | 56.6 (12.7) | 56.1 (12.6) |

| CGI-Severity score, mean (s.d.) | 3.1 (0.7) | 3.1 (0.8) | 3.0 (0.8) |

| CGI-Improvement score, mean (s.d.) | 3.2 (0.9) | 3.3 (0.9) | 3.1 (1.0) |

CGI, Clinical Global Impression; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

Efficacy

Primary outcome (ITT sample)

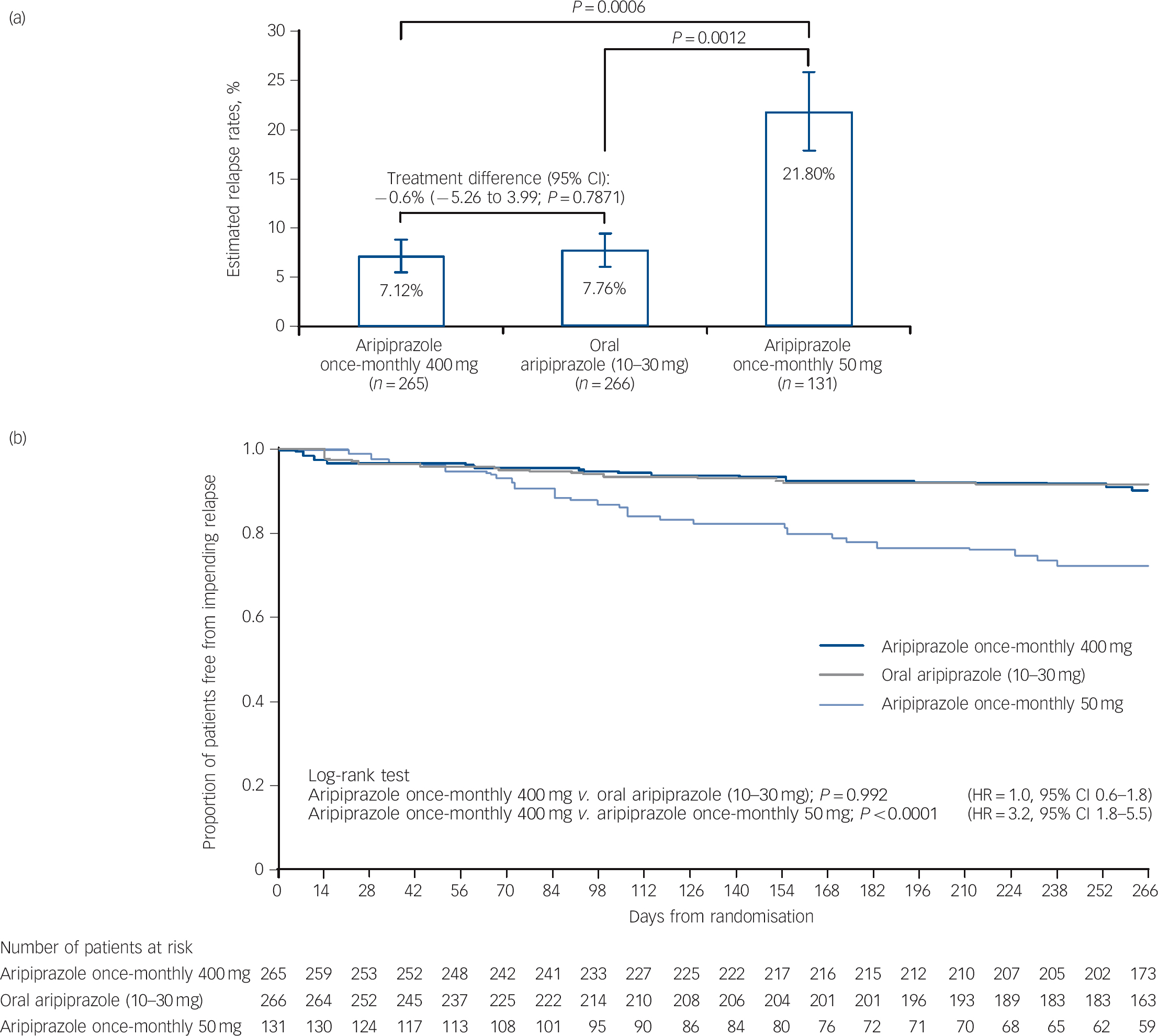

Kaplan-Meier estimated impending relapse rates at week 26 were 7.12% for aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg, 7.76% for oral aripiprazole and 21.80% for aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg (Fig. 2a). The difference of Kaplan-Meier estimated impending relapse rate by week 26 between aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg and oral aripiprazole was –0.64% (95% CI –5.26 to 3.99), which confirmed non-inferiority by excluding the predefined non-inferiority margin of 11.5%. Superiority of aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg was shown v. aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg (P⩽0.001 from z-statistics), confirming assay sensitivity. Observed impending relapse rates at week 26 were similar to the Kaplan-Meier estimate impending relapse rates: aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg, 6.79% (18/265); oral aripiprazole (10-30 mg), 7.14% (19/266); aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg, 18.32% (24/131); confirming non-inferiority for aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg v. oral aripiprazole (95% CI –5.06 to 4.36, P = 0.8740), and superiority v. aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg (95% CI –19.38 to –3.67, P = 0.0005).

Fig. 2 (a) Kaplan-Meier estimated impending relapse rates at week 26 (intention-to-treat (ITT) sample) and (b) time to observed impending relapse at week 38 (ITT sample).

In (a) whiskers indicate standard error. HR, hazard ratio.

Secondary efficacy outcomes

Time to observed impending relapse and observed rate of impending relapse at week 38 (ITT sample). Time to observed impending relapse for aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg was similar to that for oral aripiprazole (log-rank test, P = 0.992), with both treatments demonstrating statistically significant delays in impending relapse v. aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg (P<0.0001) up to week 38 (Fig. 2b). The proportion of observed impending relapsers and the risk of observed impending relapse at week 38 showed comparable and statistically significant benefits with aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg v. aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg (P<0.0001; Table 2).

Table 2 Secondary and other efficacy outcomes (week 38)

| P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy outcome | Aripiprazole once- monthly 400 mg (n = 265) | Oral aripiprazole 10-30 mg | Aripiprazole once- monthly 50 mg (n = 131) | Aripiprazole once- monthly 400 mg v. oral aripiprazole 10-30 mg | Aripiprazole once- monthly 400 mg v. aripiprazole once- monthly 50 mg |

| Observed impending relapseFootnote a (ITT sample) | |||||

| Proportion of observed impending relapsers, % (n/N) | 8.30 (22/265) | 7.89 (21/266) | 22.14 (29/131) | 0.8635 | <0.0001 |

| Risk of observed impending relapse v. aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg, | 3.158 (1.81-5.50) | 3.131 (1.78-5.49) | |||

| HR (95% CI) P | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||

| Responders (ITT sample) and remitters, % (n/N) | |||||

| Proportion of responders | 89.8 (237/264) | 89.4 (235/263) | 75.2 (97/129) | 0.8750 | 0.0001 |

| Proportion of remitters | 48.8 (105/215)Footnote b | 53.2 (107/201)Footnote b | 59.7 (43/72)Footnote b | 0.3700 | 0.1097 |

| PANSS Total score (efficacy sample, LOCF) | |||||

| n | 263 | 266 | 131 | ||

| Baseline, least square mean (s.e.) | 57.94 (0.79) | 56.57 (0.78) | 56.08 (1.11) | 0.2179 | 0.1751 |

| Change from baseline at week 38, least square mean (s.e.) | −1.66 (0.72) | 0.58 (0.71) | 3.08 (1.01) | 0.0272 | 0.0002 |

| CGI - Severity (efficacy sample, LOCF) | |||||

| n | 259 | 263 | 129 | ||

| Baseline, least square mean (s.e.) | 3.12 (0.05) | 3.09 (0.05) | 2.95 (0.07) | 0.7262 | 0.0605 |

| Change from baseline at week 38, least square mean (s.e.) | −0.13 (0.05) | 0.05 (0.05) | 0.23 (0.07) | 0.0123 | <0.0001 |

| CGI - Improvement (efficacy sample, LOCF) | |||||

| n | 265 | 266 | 131 | ||

| Baseline, mean (s.d.) | 3.24 (0.91) | 3.26 (0.90) | 3.08 (1.02) | 0.7830 | 0.1306 |

| At week 38, mean (s.d.) | 3.27 (1.16)Footnote c | 3.66 (1.16) | 4.02 (1.32) | 0.0002 | <0.0001 |

ITT, intent to treat; HR, hazard ratio; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; LOCF, last observation carried forward; CGI, Clinical Global Impression.

a Impending relapse was defined as in Method.

b Only patients who remained in the trial for at least 6 months (i.e. the proportion of patients without impending relapse at 6 months) were included as the denominator in the calculation of remission rates. Remission was defined as in Method.

c n = 263.

Responders (ITT sample) and remitters. There was a statistically significant greater proportion of responders with aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg v. aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg (P = 0.0001, Table 2). The proportion of remitters did not show any statistically significant differences between treatment groups, although the proportion of patients remaining in the study for 6 months in the aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg group was lower (n = 72/131, 55.0%) than in the aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg group (n = 215/265, 81.1%) or the oral aripiprazole group (n = 201/266, 75.6%) (Table 2).

Other efficacy outcome measures

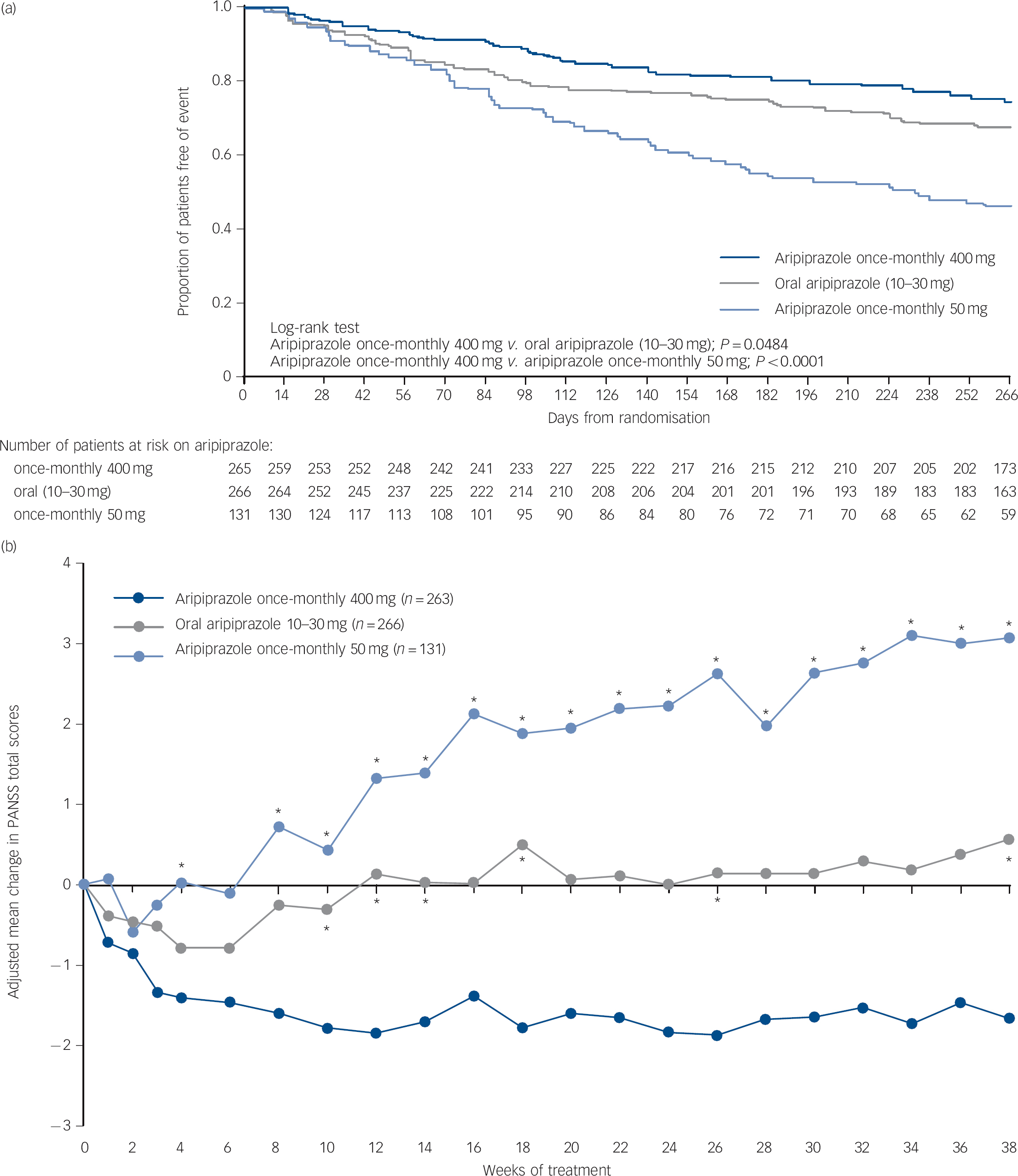

Time to all-cause discontinuation (ITT sample). A statistically significant advantage on the Kaplan-Meier time to discontinuation favouring aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg was observed v. oral aripiprazole (P<0.05) and v. aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg (P<0.0001, Fig. 3a). The all-cause discontinuation rate (a measure of effectiveness) was 25.3% (n = 67/265) for aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg, 32.7% (n = 87/266) for oral aripiprazole and 53.4% (n = 70/131) for aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg.

Fig. 3 (a) Time to all-cause discontinuation during phase 3 (intention-to-treat sample); (b) adjusted mean change of PANSS total score in phase 3 (efficacy sample, last-observation-carried-forward).

(a) Refers to patients that discontinued prior to or on day 280 in phase 3. (b) *P<0.05 v. aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg. PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

PANSS, CGI-S, and CGI-I (efficacy sample, LOCF). Symptom measures using PANSS, CGI-S and CGI-I showed statistically significant differences for aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg v. both oral aripiprazole and aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg (Table 2). Mean changes from baseline to end-point in adjusted mean PANSS total score (efficacy sample, LOCF) are shown in Fig. 3b. Statistically significant differences in mean change in PANSS total score between aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg and oral aripiprazole were observed at weeks 10-14, 18, 26 and study end-point (P<0.05). Statistically significant differences in the aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg group v. the aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg group were observed at week 4 and from week 8 onwards (P<0.05). Data for other efficacy end-points in the efficacy sample for observed cases can be found in online Table DS1.

Safety and tolerability (safety sample, observed cases)

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (⩾5% in any group) are presented in Table 3. For aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg, insomnia, akathisia, headache and weight decrease/increase were reported by 9-12% of patients (Table 3). The majority of treatment-emergent adverse events reported in the randomised phase were mild or moderate in severity.

Table 3 Treatment-emergent adverse events reported in ⩾5% of patients in any treatment group during the randomised phase (safety sample)Footnote a

| n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse event | Aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg (n = 265) | Oral aripiprazole 10-30 mg (n = 266) | Aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg (n = 131) |

| Any treatment-emergent adverse event | 219 (82.6) | 213 (80.1) | 106 (80.9) |

| Insomnia | 31 (11.7) | 37 (13.9) | 18 (13.7) |

| Akathisia | 28 (10.6)Footnote b | 18 (6.8) | 11 (8.4) |

| Headache | 26 (9.8) | 30 (11.3) | 7 (5.3) |

| Weight decreased | 26 (9.8) | 16 (6.0) | 12 (9.2) |

| Weight increased | 24 (9.1) | 35 (13.2) | 7 (5.3) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 21 (7.9) | 25 (9.4) | 9 (6.9) |

| Injection-site pain | 20 (7.5) | 6 (2.3) | 1 (0.8) |

| Anxiety | 19 (7.2) | 13 (4.9) | 10 (7.6) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 18 (6.8) | 11 (4.1) | 5 (3.8) |

| Influenza | 11 (4.2) | 11 (4.1) | 7 (5.3) |

| Back pain | 10 (3.8) | 14 (5.3) | 15 (11.5) |

| Psychotic disorder | 8 (3.0) | 8 (3.0) | 8 (6.1) |

| Schizophrenia | 8 (3.0) | 5 (1.9) | 10 (7.6) |

a Patients with multiple treatment-emergent adverse events within the same category were counted only once towards category total.

b One patient in the aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg group experienced an akathisia-related event (psychomotor hyperactivity) in addition to the 28 who experienced akathisia.

During the randomised phase, serious treatment-emergent adverse events were reported in a total of 41/662 (6.2%) patients: 15/265 (5.7%) treated with aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg; 15/266 (5.6%) treated with oral aripiprazole; and 11/131 (8.4%) treated with aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg. Serious treatment-emergent adverse events reported in ⩾2% of patients were only observed for patients treated with aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg, and were psychiatric disorder (n = 4, 3.1%) and schizophrenia (n = 3, 2.3%). Two deaths were reported, one as a result of cardiac arrest in the oral aripiprazole group (15 mg dose, 51-year-old male) and one as a result of suicide in the aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg group (44-year-old male). Neither death was considered by the investigator to be related to the trial medication.

During the randomised phase, discontinuation of double-blind medication due to treatment-emergent adverse events (including impending relapse with adverse events) was reported in 21/265 (7.9%) patients in the aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg group, 19/266 (7.1%) patients in the oral aripiprazole group and 24/131 (18.3%) of patients in the aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg group. Treatment-emergent adverse events resulting in discontinuation that occurred in ⩾2% of patients in any treatment group were psychotic disorder (4/265 (1.5%) aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg; 5/266 (1.9%) oral aripiprazole; 8/131 (6.1%) aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg) and schizophrenia (8/265 (3.0%) aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg; 5/266 (1.9%) oral aripiprazole; 9/131 (6.9%) aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg). No patients discontinued study treatment because of akathisia.

During the randomised phase, 58/265 (21.9%) patients in the aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg group, 31/266 (11.7%) in the oral aripiprazole group and 16/131 (12.2%) in the aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg group had treatment-emergent EPS and EPS-related treatment-emergent adverse events. These EPS and EPS-related events reported by ⩾5% of patients were akathisia events (29/265, 10.9%) and Parkinsonism events (15/265, 5.7%) in the aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg group, akathisia (18/266, 6.8%) in the oral aripiprazole group and akathisia (11/131, 8.4%) and Parkinsonism events (7/131, 5.3%) in the aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg group. Extrapyramidal symptoms were also monitored using physician- and patient-rated scales (Table 4). No statistically significant differences in SAS, AIMS or BARS least squares mean score changes were observed for aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg v. aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg; the difference in BARS was statistically significant for aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg (0.06) v. oral aripiprazole (-0.05). The score for CGI-SS and the C-SSRS suicidal ideation intensity total score remained stable across treatment groups throughout the double-blind active-controlled phase (Table 4). See online Table DS3 for LOCF data on EPS and suicidality in the safety sample.

Table 4 Extrapyramidal symptoms and suicidality during exposure to aripiprazole (safety sample, observed cases)Footnote a

| Aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg (n = 265) | Oral aripiprazole 10-30 mg (n = 266) | Aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg (n = 131) | P | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Baseline, mean | Change from baseline at week 38 | n | Baseline, mean | Change from baseline at week 38 | n | Baseline, mean | Change from baseline at week 38 | Aripiprazole once monthly 400 mg v. oral aripiprazole 10-30 mg | Aripiprazole once- monthly 400 mg v. aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg | |

| Extrapyramidal symptoms | Least square | Least square | Least square | ||||||||

| mean (s.e.) | mean (s.e.) | mean (s.e.) | |||||||||

| SAS total scoreFootnote b | 192 | 10.88 | −0.16 (0.09) | 171 | 11.12 | −0.22 (0.09) | 61 | 10.70 | −0.21 (0.16) | 0.6379 | 0.7911 |

| AIMS movement rating scoreFootnote c | 192 | 0.36 | −0.00 (0.07) | 171 | 0.42 | −0.11 (0.07) | 61 | 0.34 | −0.01 (0.12) | 0.2584 | 0.9845 |

| BARS global scoreFootnote d | 192 | 0.15 | 0.06 (0.03) | 171 | 0.14 | −0.05 (0.03) | 61 | 0.13 | −0.06 (0.06) | 0.0184 | 0.0708 |

| Suicidality | Mean (s.d.) | Mean (s.d.) | Mean (s.d.) | ||||||||

| CGI-SSFootnote e | 192 | 1.02 | −0.01 (0.10) | 171 | 1.01 | 0.00 (0.00) | 61 | 1.02 | −0.02 (0.13) | NA | NA |

| C-SSRSFootnote e | 86 | 0.2 | −0.1 (1.0) | 78 | 0.1 | 0.1 (1.3) | 31 | 0.0 | 0.0 (0.0) | NA | NA |

CGI-SS Clinical Global Impression of Severity of Suicidality; C-SSRS, Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale, NA, not applicable.

a. Data for patients with baseline and at least one post-baseline result during the double-blind active-controlled phase.

b. Simpson-Angus Scale (SAS): sum of ten Parkinsonian symptom items; each rated on a five-point scale (1, absence of symptoms; 5, severe condition).

c. Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS): sum of seven items related to facial, oral, extremity, or trunk movements; each item rated on a five-point scale (0, absence of symptoms; 4, severe condition).

d. Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (BARS): derived from the global clinical assessment of akathisia; rated on a six-point scale (0, absence of symptoms; 5, severe akathisia).

e. Change from baseline was evaluated with a seven-point scale (1, very much improved; 7, very much worse).

Rates of concomitant anticholinergic use during phase 3 were 19.6% (n = 52/265; mean daily dose, 1.61 mg) for aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg, 17.3% (n = 46/266; mean daily dose, 1.50 mg) for oral aripiprazole, and 13.7% (n = 18/131; mean daily dose, 1.66 mg) for aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg. Concomitant benzodiazepine use data are reported in the online supplement DS1.

Mean changes in body weight at week 38 of +0.1 kg (s.d. = 4.8), +1.0 kg (s.d. = 4.8), and –1.6 kg (s.d. = 7.4) for aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg, oral aripiprazole, and aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg, respectively. The difference was statistically significant at week 38 (P<0.05) for aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg v. aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg. The incidence of clinically relevant weight gain (⩾7% increase in weight from baseline) at any time during the randomised phase was 15.9% (n = 42/264) for aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg, 16.2% (n = 43/266) for oral aripiprazole and 6.1% (n = 8/131) for aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg. The incidence of clinically relevant weight loss (⩾7% decrease in weight from baseline) at any time during the randomised phase was 15.2% (n = 40/264) for aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg, 10.2% (n = 27/266) for oral aripiprazole and 13.7% (n = 18/131) for aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg.

There were no differences in mean change in metabolic parameters, and the incidence of potentially clinically relevant new-onset metabolic parameter abnormalities was low and similar among treatment groups (online Table DS2). Similar findings were observed for prolactin (online Table DS2). There were also no clinically relevant changes in ECG parameters and no incidents of new-onset QTcF (QT interval as corrected for heart rate by Fridericia’s formula) increases >500 ms during double-blind treatment.

Injection-site pain occurred in 7.5% (20/265) of patients in the aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg group, 2.3% (6/266) of the oral aripiprazole group and 0.8% (1/131) of the aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg group. Mean intensity of pain, measured using a patient-reported 100-point VAS scale (0 mm, no pain; 100 mm, unbearably painful) showed mild pain during the double-blind treatment phase, with reductions being reported from the first to last injection with aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg (5.6-3.7 mm), oral aripiprazole (4.9-3.5 mm) and aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg (3.3-2.4 mm). Absence of any pain, redness, swelling and induration by investigators’ evaluations was found for the majority of patients following the first and last injections of aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg.

Discussion

Main findings

The current study showed that aripiprazole once-monthly at a dose of 400 mg is non-inferior to oral aripiprazole (10-30 mg) and superior to aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg on the primary outcome of Kaplan-Meier estimated rate of impending relapse at week 26. The secondary outcome, delay in time to observed impending relapse, was statistically significant with aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg compared with aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg at week 38. Also, the delay in time to all-cause discontinuation (non-primary/non-secondary outcome) was statistically significant with aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg compared with both the oral and aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg groups.

Other findings

On other (non-primary/non-secondary) efficacy measures (PANSS, CGI-S and CGI-I), there were statistically significant differences for aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg v. both aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg and oral aripiprazole. Although statistically significant, the clinical relevance of the absolute changes in PANSS total score is difficult to interpret. Prior research on the association between CGI-S and PANSS scores suggests that a mild CGI-S score (i.e. 3) corresponds with a PANSS total score of 55-62,Reference Levine, Rabinowitz, Engel, Etschel and Leucht18 indicating that at baseline in the double-blind, active-controlled phase of the current study, patients demonstrated mild symptoms across treatment groups. Prior research also indicates that no change on the CGI-I (i.e. CGI-I score of 4) corresponds with PANSS percentage change score reductions of 2-3%.Reference Levine, Rabinowitz, Engel, Etschel and Leucht18 Thus, in the current study, the statistically significant treatment differences favouring aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg v. oral aripiprazole and aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg in PANSS total score may be of minimal clinical relevance (treatment differences in least square mean change scores ranged from ∼2 to 5 points) because the overall disease severity of patients in all three groups was relatively unchanged. Modest changes in PANSS may be consistent with clinical expectations for patients who were already stabilised with oral aripiprazole therapy.

The safety profile of aripiprazole once-monthly was comparable with oral aripiprazole and consistent with that reported for oral aripiprazole in previous registrational maintenance studies.Reference Kane, Sanchez, Perry, Jin, Johnson and Forbes3,Reference Pigott, Carson, Saha, Torbeyns, Stock and Ingenito17,Reference Kasper, Lerman, McQuade, Saha, Carson and Ali19 The safety profile reported here is also consistent with data from another maintenance study of aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg v. placebo.Reference Kane, Sanchez, Perry, Jin, Johnson and Forbes3 Metabolic changes, weight changes and EPS-related changes were generally comparable across registrational maintenance studies of both oral and once-monthly formulations. The clinical relevance of the statistically significant change in BARS global score observed at week 38 with aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg v. oral aripiprazole in the current study is unknown. In general, the overall rates of treatment-emergent adverse events, including akathisia, were lower in the maintenance study reported by Kane et al,Reference Kane, Sanchez, Perry, Jin, Johnson and Forbes3 possibly because of the study design, which required patients to be stabilised on aripiprazole once-monthly for 3 months prior to randomisation. There was no requirement for stabilisation on once-monthly aripiprazole prior to randomisation in the current study. As previously observed,Reference Kane, Sanchez, Perry, Jin, Johnson and Forbes3 injections were well tolerated; numerically higher rates of injection-site pain treatment-emergent adverse events were observed for aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg compared with aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg; however, across all treatment groups, patients reported mild injection pain, with reductions in self-reported injection pain scores from the first to last injection.

Advantages and disadvantages of LAIs

Recent guideline updates from the World Federation of Societies of Biological PsychiatryReference Hasan, Falkai, Wobrock, Lieberman, Glenthoj and Gattaz20 suggest that the potential advantages of LAI antipsychotics v. oral antipsychotics include improved adherence to treatment, avoidance of gastrointestinal absorption problems and circumvention of first-pass hepatic metabolism. Potential disadvantages of LAIs include diminished flexibility of administration, potential for injection-site reactions and delayed attenuation of adverse effects after treatment discontinuation.Reference Hasan, Falkai, Wobrock, Lieberman, Glenthoj and Gattaz20 The potential benefit of aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg over the oral and 50 mg dose on time to all-cause discontinuation complements a recent large national cohort study in Finland of 2588 patients admitted to hospital with newly diagnosed schizophrenia, which found that patients treated with LAIs had a lower risk of readmissions to hospital in comparison with those treated with oral formulations of the same antipsychotic medications.Reference Tiihonen, Haukka, Taylor, Haddad, Patel and Korhonen21 In contrast, a controlled clinical study in the USA reported rates of readmission that were comparable between LAI risperidone and any oral antipsychotic therapy.Reference Rosenheck, Krystal, Lew, Barnett, Fiore and Valley22 Recent meta-analyses suggest that differences between oral and LAI formulations are less likely to be found in controlled clinical trials where adherence is enhanced owing to multiple clinic visits and more likely to be observed in naturalistic studies.Reference Kirson, Weiden, Yermakov, Huang, Samuelson and Offord23,Reference Kishimoto, Robenzadeh, Leucht, Leucht, Watanabe and Mimura24

Limitations

In the current study, treatment initiation of aripiprazole once-monthly in the randomised phase was carried out in patients who had been stabilised with oral aripiprazole. However, in clinical practice, patients may be switched directly from their current oral antipsychotic to an LAI antipsychotic. This difference from real-life clinical populations may limit the generalisability of our findings. The study population was also limited to patients with chronic schizophrenia of mild severity, which may have contributed to the low rates of relapse and may also limit the generalisability of our findings. Also, because of the very low initial relapse rates, the primary outcome was adjusted (as approved by the EMA; see online supplement DS1) from time to observed impending relapse at week 38 to Kaplan-Meier estimated relapse rates at week 26, because time as a variable can have a disproportional impact on time to events when event rates are low. Revising the primary outcome after the trial started may have introduced some bias; however, the total impending relapse events remained low for the duration of the study, the estimated sample size was slightly increased and non-inferiority v. oral aripiprazole was clearly demonstrated. In addition, the study did not consider the potential for multiple testing concerns, which may have limited the strength of the prespecified statistical analysis plan for secondary and other efficacy outcomes. Another potential limitation is that our trial may not have been long enough to fully detect potential differences between the once-monthly and the oral formulations of aripiprazole.

Funding

This study was supported by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Commercialization, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). Editorial support for the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Suzanne Patel at Ogilvy Healthworld Medical Education and Amy Roth Shaberman, PhD, and Brett D. Mahon, PhD, at C4 MedSolutions, LLC, a CHC Group company; funding was provided by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Commercialization, Inc. and H. Lundbeck A/S.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Svetlana Ivanova, PhD, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA, for her contribution to the analysis and interpretation of data.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.