Psychotic disorders are marked by heterogeneity in terms of clinical presentation and outcome. Reference Tandon, Nasrallah and Keshavan1 Historically, schizophrenia was conceptualised as a chronic, progressively deteriorating condition. However, there is increasing recognition that people with schizophrenia can experience symptomatic improvements and regain a degree of social and occupational functioning. Reference Zipursky, Reilly and Murray2 Over the past 20 years there has been an increased focus on specialist early intervention services for first-episode psychosis (FEP). Reference McGorry, Johanessen, Lewis, Birchwood, Malla and Nordentoft3,Reference Craig, Garety, Power, Rahaman, Colbert and Fornells-Ambrojo4 However, it remains unclear what the outcomes are for people with FEP (including those with a first episode of schizophrenia) in terms of remission and recovery. To our knowledge, only three systematic reviews and two meta-analyses have considered recovery or remission in FEP and/or schizophrenia. Reference Warner5–Reference Jaaskeläinen, Juola, Hirvonen, McGrath, Saha and Isohanni9 The most recent systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that only 13.5% of patients with schizophrenia met the criteria for recovery, although the follow-up period was not given, and this review included people with both first-episode and multi-episode disorder. Reference Jaaskeläinen, Juola, Hirvonen, McGrath, Saha and Isohanni9 Patients with multiple episodes include those with more chronic or treatment-resistant illness, who would by definition be expected to have lower recovery rates. A systematic review in FEP identified ‘good’ outcomes for 42% of patients with psychosis and 31% of those with schizophrenia, Reference Menezes, Arenovich and Zipursky7 whereas a later review of remission in FEP identified an average remission rate of 40% (range 17–78%). Reference AlAqeel and Margolese6 These reviews are limited by the wide variety of outcome definitions used, Reference Menezes, Arenovich and Zipursky7 in keeping with a paucity of identified studies using standardised definitions of remission or recovery, the small number of included studies, Reference AlAqeel and Margolese6 and the absence of a FEP review including a meta-analysis. Although naturalistic FEP outcome studies of increasing sophistication and duration have been published, Reference Henry, Amminger, Harris, Yuen, Harrigan and Prosser10–Reference Evensen, Rossberg, Barder, Haahr, Hegelstad and Joa13 the longer-term outcomes for these patients in terms of remission and recovery rates remain uncertain. This deficiency in the literature is important, because since the introduction of the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group (RSWG) criteria for remission in 2005, many studies in FEP have sought to use the operationalised criteria for remission in schizophrenia. Reference Andreasen, Carpenter, Kane, Lasser, Marder and Weinberger14

We therefore conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess pooled prevalence rates of remission and recovery in FEP and schizophrenia in longitudinal studies. In addition, we sought to identify potential moderators of remission and recovery. Finally, we sought to investigate whether specific variables have an impact on remission and recovery proportions (e.g. narrow and broad remission and recovery definitions, duration of follow-up, region of study and study year). Our a priori hypotheses were the following:

-

(a) a greater proportion of patients with FEP would meet criteria for remission and recovery in studies from the past 20 years compared with earlier studies;

-

(b) recovery would be less prevalent in samples with longer duration of follow-up compared with shorter follow-up;

-

(c) rates of remission and recovery would be lower when defined with narrow criteria.

Method

This systematic review was conducted in accord with the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses standard. Reference Stroup, Berlin, Morton, Olkin, Williamson and Rennie15,Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman16

Inclusion criteria

We included studies of longitudinal observational design (both retrospective and prospective studies) in patients over 16 years old (with no upper age limit) that fulfilled the following criteria.

Remission

Studies reporting remission rates in people with a first psychotic episode (including schizophrenia and affective psychosis) irrespective of clinical setting (in-patient, out-patient or mixed) were included. Remission has been operationalised in terms of symptomatic and/or functional improvement with a duration component. The use of the RSWG criteria has become common over the past decade, measuring both an improvement in symptoms and duration criteria (> 6 months) for persistence of mild or absent symptoms. Reference Andreasen, Carpenter, Kane, Lasser, Marder and Weinberger14 We categorised remission criteria as ‘broad’ or ‘narrow’. Narrow criteria studies were those using the RSWG criteria, comprising two dimensions: symptom severity (mild or absent) and duration (mild or absent symptoms for at least 6 months), or those defining remission as patients being asymptomatic and attaining premorbid functioning sustained for at least 6 months. Broad criteria studies were those that defined symptomatic remission but not duration.

Recovery

Recovery has been operationalised as a multidimensional concept, incorporating symptomatic and functional improvement in social, occupational and educational domains, with a necessary duration component (> 2 years). Reference Jaaskeläinen, Juola, Hirvonen, McGrath, Saha and Isohanni9,Reference Warner17,Reference Leucht and Lasser18 We mirrored the approach of Jääskeläinen et al, categorising those studies in which both clinical and functioning dimensions are operationally assessed, along with a duration of sustained improvement for ⩾ 2 years. Reference Jaaskeläinen, Juola, Hirvonen, McGrath, Saha and Isohanni9 We further analysed recovery in relation to studies in which both clinical and level of functioning dimensions were assessed, but with a duration for sustained improvement of > 1 year. We categorised as broad recovery criteria those studies in which either one or none of the symptom improvement and functioning dimensions were used and/or with an insufficient duration criterion.

Treatment contact

Samples were restricted to people with FEP who were making their first treatment contact (in both in-patient and out-patient settings).

Diagnostic system

Only studies using a specified standardised diagnostic system such as ICD versions 8, 9 and 10, DSM-III and -IV, Kraepelin & Feighner's diagnostic criteria, Royal Park Multidiagnostic Instrument for Psychosis and the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) were included.

Other criteria

Study samples were restricted to those that included only individuals with FEP and/or first-episode schizophrenia and/or first-episode affective psychosis. When more than one diagnostic group was identified in a sample, that study was included only if the number in each subgroup was identified. Studies were required to have a follow-up period of at least 12 months, and adequate follow-up data to allow remission or recovery rates to be determined (e.g. studies reporting only the mean difference in symptom rating scales between groups or correlations were excluded). Articles had to be published in a peer-reviewed journal from database inception to July 2016, with no language restriction applied.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded randomised controlled trials, because of the potential for any structured intervention beyond routine care to influence our primary outcomes, as well as studies of organic psychosis.

Search criteria

Two authors (J.L. and O.A.) independently searched PubMed, Medline and Scopus without language restrictions from database inception until 1 July 2016. Key words used were first episode psychosis OR early episode psychosis OR schizophrenia OR schiz* AND remission OR recovery AND outcome OR follow-up. Manual searches were also conducted using the reference lists from recovered articles and recent reviews. Reference AlAqeel and Margolese6,Reference Menezes, Arenovich and Zipursky7,Reference Jaaskeläinen, Juola, Hirvonen, McGrath, Saha and Isohanni9

Data extraction

Two authors (J.L. and O.A.) extracted all data, and any inconsistencies were resolved by consensus or by a third author (B.S.). One author (O.A.) extracted data using a predetermined data extraction form, which was subsequently validated by a second author (J.L.). The data extracted included first author, country, setting, population, study design (e.g. prospective, retrospective), participants included in the study (including mean age, % female), diagnostic classification method, method of assessment (e.g. face-to-face interviews, case records or combination of both approaches), duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), sociodemographic characteristics of the sample (percentage employed, single or in a stable relationship at study entry), baseline psychotic symptoms (mean scores), length of study follow-up, participant loss at follow-up and criteria used to define remission and recovery. When studies reported on overlapping samples, details of the study with the longest follow-up period were included, or if this was unclear, studies with the largest study sample for each respective outcome were included. We included multisite studies, and retained data for the entire cohort and not for individual sites.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes were the proportions of people with FEP who met the criteria for remission and recovery respectively over the course of each study as defined above.

Statistical analysis

Owing to the anticipated heterogeneity across studies, we conducted a random effects meta-analysis, in the following sequence. First, we calculated the pooled prevalence rates of remission and recovery in FEP. Second, to account for attrition bias, we imputed a remission and recovery rate using the principle of worst-case scenario, assuming that all people who left the study did not have a favourable outcome. Third, we calculated the subgroup differences in remission and recovery according to whether a narrow or broad definition of remission or recovery was used; the first-episode diagnosis category; the method used to assess remission and recovery (structured face-to-face assessment, structured assessment supplemented with clinical notes and/or interviews with parents; clinical records); duration of follow-up (categorised into three groups: 1–2 years, 2–6 years and >6 years based on ascending duration of follow-up (tertiles); region of study; study period (we selected the midpoint of the study period as the study year, and categorised this by adapting criteria proposed by Warner (recovery studies pre-1975, 1976–1996 and 1997–2016; remission studies pre-1975, 1976–1996, 1997–2004 and 2005–2016); Reference Warner5 study design; and the setting of the study at first episode (in-patient; community and early intervention services; and mixed in- and out-patient psychiatric services). Fourth, we conducted meta-regression analyses to investigate potential moderators of remission and recovery: age, percentage of men, ethnicity, baseline psychotic symptoms (mean scores), relationship and employment status at first contact, DUP, duration of follow-up, attrition rate and study year. Publication bias was assessed with the funnel plot, Egger's regression test and the trim and fill method. Reference Egger, Davey Smith, Schneider and Minder19,Reference Duvall and Tweedie20 Heterogeneity was measured with the Q statistic, yielding chi-squared and P values, and the I 2 statistic with scores above 50% and 75% indicating moderate and high heterogeneity respectively. Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman21 Finally, descriptive statistical methods were used for the exploratory summary of study-reported correlates of remission and recovery based on patient-level data not available for study-level meta-regression analyses. All analyses were conducted with Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software version 3 and Stata release 14.

Results

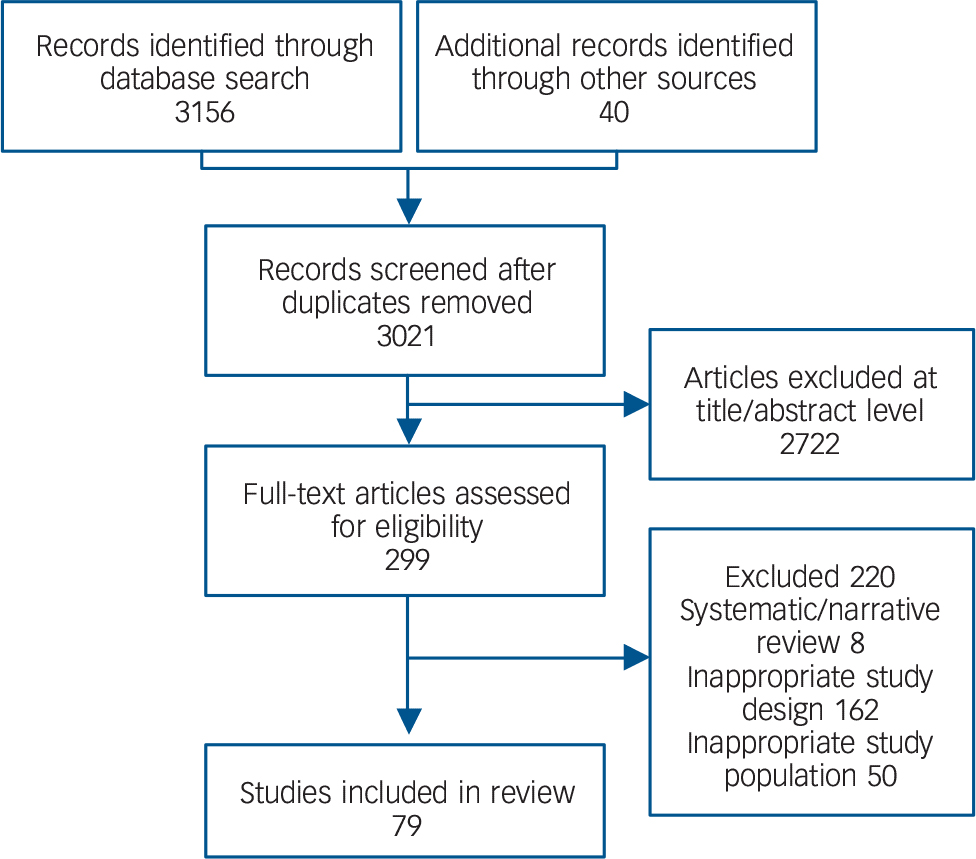

Our search yielded 3021 non-duplicated publications, which were considered at the title and abstract level; 299 full texts were reviewed, of which 79 met inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Reference Henry, Amminger, Harris, Yuen, Harrigan and Prosser10–Reference Evensen, Rossberg, Barder, Haahr, Hegelstad and Joa13,Reference Harrow, Grossman, Jobe and Herbener22–Reference Faber, Smid, Van Gool, Wunderink, van den Bosch and Wiersma96 Full details of the included studies are given in online Tables DS1 and DS2. There were 44 studies reporting on remission rates and 19 reporting on recovery rates, with 16 studies reporting on both remission and recovery, for a total of 79 independent samples. The final sample comprised 19 072 patients with FEP (range of sample sizes 13–2842); 12 301 (range 13–2210) with remission data and 9642 (range 25–2842) with recovery data.

Fig. 1 Study selection process: only 79 studies were eligible for pooling in the meta-analysis.

In the remission sample the mean age of the patients at study recruitment was 26.3 years (median 25.7, range 15.6–42.3) and 40.6% were female. The mean DUP (25 studies) was 433.2 days, s.d. = 238.9, interquartile range (IQR) 265.0–541.4. The mean follow-up period was 5.5 years (60 studies, s.d. = 5.3, IQR = 2.0–7.0). In the recovery sample the mean age of the patients at study recruitment was 27.3 years (median 26.0, range 24.2–28.5) and 41.1% were female. The mean DUP (11 studies) was 359.2 days (s.d. = 215.4, IQR = 226.3–492.8). The mean follow-up period was 7.2 years (35 studies, s.d. = 5.6, IQR = 2.0–10.0).

Remission

The pooled rate of remission among 19 072 individuals with FEP was 57.9% (95% CI 52.7–62.9, Q = 1536.3, P < 0.001, N = 60) (online Fig. DS1). The Begg–Mazumdar (Kendall's tau b = 0.151, P = 0.09) and Egger test (bias = 0.98, 95% CI −1.42 to 3.38, P = 0.47) indicated no publication bias. A visual inspection of the funnel plot revealed some asymmetry, and we adjusted for this asymmetry and potential missing studies (online Fig. DS2). The trim and fill method demonstrated that the prevalence of remission was unaltered when adjusted for potential missing studies. Restricting the analysis to studies that used the RSWG criteria for remission (25 studies, n = 6909), the overall pooled prevalence remission rate was 56.9% (95% CI 48.9–64.5, Q = 656.9, 25 studies). Using the worst-case scenario the remission rate was 39.3% (95% CI 35.1–43.5, Q = 1371, 55 studies).

Subgroup analyses

Full details of the proportion of people who experienced remission, together with heterogeneity and trim and fill analyses, are summarised in online Table DS3, and a shortened version is given in Table 1. Results of interest are briefly discussed below.

Table 1 Meta-analysis of remission in patients with first-episode psychosis

| No. of studies | Pooled prevalence % (95% CI) |

Between-group P |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Remission main analysis | 60 | 57.89 (52.68–62.93) | |

| Remission worst-case scenario | 55 | 39.30 (35.10–43.50) | |

| Narrow validity | 0.721 | ||

| No | 14 | 54.79 (43.27–65.83) | |

| Yes | 27 | 56.64 (48.36–64.57) | |

| Valid by symptomatic remission but not duration | 17 | 63.01 (52.43–72.47) | |

| Broad validity | 0.9112 | ||

| No | 29 | 56.74 (49.14–64.03) | |

| Yes | 29 | 58.80 (51.38–65.84) | |

| Duration criteria for remission | 0.414 | ||

| 1–12 weeks | 17 | 62.44 (52.51–71.43) | |

| 3–6 months | 27 | 56.71 (48.86–64.24) | |

| 9 months or longer | 2 | 45.91 (21.57–72.37) | |

| At final assessment | 6 | 67.38 (50.21–80.88) | |

| Not stated | 6 | 45.59 (30.05–62.03) | |

| Remission according to RSWG criteria | 0.742 | ||

| No | 35 | 58.60(51.78–65.11) | |

| Yes | 25 | 56.87 (48.93–64.47) | |

| Study year | 0.181 | ||

| Before 1976 | 2 | 29.51 (12.53–55.02) | |

| 1976–1997 | 18 | 59.33 (50.08–67.97) | |

| 1997–2004 | 27 | 58.66 (51.29–65.67) | |

| 2005–2016 | 13 | 58.57 (47.51–68.84) | |

| Study region | 0.002 a | ||

| North America | 17 | 65.19 (56.62–72.88) | |

| Europe | 27 | 52.71 (46.06–59.26) | |

| Asia | 10 | 66.35 (55.81–75.48) | |

| Africa | 2 | 73.07 (47.26–89.15) | |

| Australia | 2 | 40.29 (20.62–63.66) | |

RSWG, Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group.

a. Significant P < 0.01.

For studies only of patients with schizophrenia the pooled remission rate was 56.0% (95% CI 47.5–64.1, Q = 378.50, 25 studies), with an equivalent rate of 55.4% (95% CI 47.7–62.8, Q = 1049.0, 29 studies) for patients with FEP; the pooled remission rate was higher in the affective psychosis group (78.7%, 95% CI 63.9–88.5, Q = 68.6, 6 studies) compared with the schizophrenia group. There was no difference in remission rates in comparisons of study period, duration of follow-up, study type or setting, or proportion of studies using narrow remission criteria. Remission rates were significantly higher in studies from Africa (73.1%, 95% CI 47.2–89.1, Q = 2.48, 2 studies), Asia (66.4%, 95% CI 55.8–75.5, Q = 139.2, 2 studies) and North America (65.2%, 95% CI 56.6–72.9, Q = 192.7, 17 studies) compared with other regions (including Europe and Australia). In the study period 1976–1996, remission rates in studies from North America (65.5%, 95% CI 50.7–77.9) were significantly higher than in Europe (55.1.1%, 95% CI 35.4–73.2) or Asia (47.1%, 95% CI 38.3–56.0; P < 0.001). Equivalent remission rates were identified in the study period 1997–2004 for studies from North America (59.4%, 95% CI 52.7–65.7), Europe (55.9%, 95% CI 48.7–62.9) and Australia (56.1%, 95% CI 30.6–78.7), with significantly higher rates found in studies from Africa (82.1%, 95% CI 63.6–92.3) and Asia (71.5%, 95% CI 55.2–83.7) than in the other regions for this study period (P = 0.001). In the most recent study period (2005–2016) studies from North America (70.2%, 95% CI 42.1–88.4), Asia (69.0%, 95% CI 61.9–75.3) and Africa (63.3%, 95% CI 45.1–78.4) had increased remission rates compared with studies in Europe (45.7%, 95% CI 29.5–67.8) although this did not meet statistical significance (P = 0.09).

Moderating factors

Full details of the moderators of remission are presented in Table 2. Higher remission rates were associated with studies conducted in more recent years (β = 0.04, 95% CI 0.01–0.08, P = 0.018, R 2 = 0.10).

Table 2 Meta-regression of moderators of remission in patients with first-episode psychosis

| Number of comparisons |

β | 95% CI | P | R 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years: mean | 55 | −0.02 | −0.07 to 0.02 | 0.332 | 0.01 |

| Male, % | 57 | 0.00 | −0.02 to 0.02 | 0.920 | 0.00 |

| Baseline psychotic symptoms, mean | 32 | 0.00 | −0.01 to 0.01 | 0.464 | 0.02 |

| DUP | |||||

| Mean | 9 | 0.00 | −0.01 to 0.01 | 0.922 | 0.00 |

| Median | 24 | 0.00 | 0.00 to 0.00 | 0.167 | 0.08 |

| Taking antipsychotic medication, % | 16 | 0.01 | −0.01 to 0.02 | 0.447 | 0.03 |

| Employed, % | 17 | −0.02 | −0.05 to 0.01 | 0.125 | 0.11 |

| Single, % | 19 | 0.02 | 0.00 to 0.04 | 0.075 | 0.11 |

| Ethnicity, % | |||||

| White | 19 | 0.00 | −0.01 to 0.01 | 0.952 | 0.00 |

| Black | 15 | −0.01 | −0.05 to 0.03 | 0.535 | 0.01 |

| Asian | 12 | 0.00 | −0.01 to 0.02 | 0.693 | 0.04 |

| Drop-out, % | 49 | 0.01 | −0.01 to 0.02 | 0.222 | 0.00 |

| Length of follow-up | 57 | −0.03 | −0.07 to 0.02 | 0.239 | 0.02 |

| Study year publication | 59 | 0.04 | 0.01 to 0.08 | 0.018 | 0.10 |

DUP, duration of untreated psychosis.

Recovery

Full details of the proportion of people who recovered, together with heterogeneity and trim and fill analyses, are summarised in online Table DS4 and a shortened version is given in Table 3. The pooled rate of recovery among 9642 individuals with FEP was 37.9% (95% CI 30.0–46.5, Q = 1450.8, 35 studies, P = 0.006); see online Fig. DS3. The Begg-Mazumdar test (Kendall's tau b = −1.0, P = 0.37) and Egger test (bias 2.32, 95% CI −1.77 to −6.42, P = 0.25) indicated no publication bias. A visual inspection of the funnel plot revealed that the plot was largely symmetric (online Fig. DS4). The trim and fill method demonstrated that the prevalence of recovery was unaltered when adjusted for potential missing studies. Assuming the worst-case scenario technique, the pooled prevalence of recovery was 23.3% (95% CI 18.4–29.2, Q = 1270, 33 studies).

Table 3 Meta-analysis results of recovery in patients with first-episode psychosis

| No. of studies | Pooled prevalence % (95% CI) |

Between-group P |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Recovery main analysis | 35 | 37.90 (30.03–46.45) | |

| Recovery in worst case | 33 | 23.3 (18.4–29.2) | |

| Validity criteria | 0.001*** | ||

| Unclear criteria | 11 | 39.52 (25.52–55.47) | |

| Either clinical or social dimensions assessed | 8 | 65.98 (48.13–80.21) | |

| Both clinical and social dimensions assessed | 16 | 25.23 (16.87–35.93) | |

| Duration criterion > 1 year | 0.018* | ||

| No | 22 | 45.99 (35.30–57.05) | |

| Yes | 13 | 26.39 (16.99–38.57) | |

| Duration criterion > 2 years | 0.010** | ||

| No | 26 | 44.64 (34.82–54.90) | |

| Yes | 9 | 22.03 (12.46–35.93) | |

| Study year | 0.041* | ||

| Before 1976 | 1 | 44.46 (10.76–84.16) | |

| 1976–1997 | 9 | 45.15 (29.66–61.63) | |

| 1997–2016 | 23 | 32.09 (23.94–41.50) | |

| Study region | <0.001*** | ||

| North America | 10 | 71.01 (56.76–82.04) | |

| Europe | 14 | 21.79 (14.62–31.20) | |

| Asia | 8 | 35.05 (22.10–50.65) | |

| Multi-region | 1 | 49.15 (14.21–84.95) | |

| Australia | 2 | 28.07 (9.99–57.85) | |

| Follow-up categories | 0.044* | ||

| 1–2 years | 9 | 54.05 (38.95–68.44) | |

| 2–6 years | 11 | 32.26 (21.49–45.31) | |

| >6 years | 15 | 32.43 (23.36–43.04) | |

| Study setting | 0.004** | ||

| Adult psychiatric hospitals | 22 | 48.15 (37.82–58.64) | |

| Community and early intervention services | 4 | 18.39 (7.90–37.17) | |

| In-/out-patient psychiatric services | 9 | 24.88 (14.40–39.47) | |

* P < 0.5,

** P < 0.01,

*** P < 0.001.

Subgroup analyses

For studies using the narrowest criteria the recovery rate was 25.2% (95% CI 16.87–35.93, Q = 885.45, 16 studies). Furthermore, the pooled prevalence of recovery was significantly higher in North America (Canada and USA) (71.0%, 95% CI 56.8–82.0, Q = 150.1, 10 studies, P < 0.001) than in Europe (21.8%, 95% CI 14.6–31.2, Q = 434.2, 14 studies), Asia (35.1%, 95% CI 22.1–50.7, Q = 184.5, 8 studies) and Australia (28.1%, 95% CI 10.0–57.9, Q = 1.45, 2 studies). In the study period 1976–1996 recovery rates in studies from North America (70.3%, 95% CI 41.3–88.9) were significantly higher than in Europe (29.1%, 95% CI 5.1–75.8) and Asia (22.4%, 95% CI 9.3–4.8%) (P < 0.001). Similarly, for the most recent study period recovery rates were significantly increased in North America (85.5%, 95% CI 66.7–94.6) compared with Europe (21.2%, 95% CI 14.1–30.6) and Asia (40.6%, 95% CI 25.2–58.2) (P < 0.001).

Following the trim and fill analysis the recovery rate from North America decreased slightly to 68.5% (95% CI 48.6–83.4); there was a slight increase in the recovery rate seen in studies from Europe to 26.3% (95% CI 16.6–38.9). There was no significant difference in North American studies compared with studies from other regions in relation to attrition rate, average length of follow-up (mean duration North America 4.7 years, s.d. = 4.1, v. other regions 7.8 years, s.d. = 5.8; t = −1.46, P = 0.15), or the use of more narrow recovery criteria – although no study in North America used a recovery criterion of more than 2 years' duration, compared with 8 studies from other regions that used this criterion (χ2 = 2.77, P = 0.052). Additionally, studies with follow-up periods longer than 6 years (32.4%, 95% CI 23.4–43.0, Q = 250.5, 15 studies) or with a 2–6 year follow-up (32.30%, 95% CI 21.5–45.3, Q = 462.0, 11 studies) had significantly lower recovery rates than studies with a follow-up duration of 1–2 years (54.1%, 95% CI 39.0–68.4, Q = 167.0, 9 studies) (P = 0.044).

Equivalent rates of recovery were found in those with FEP (34.4%) and schizophrenia (30.3%) diagnoses. Those with a diagnosis of affective psychosis had a significantly increased pooled recovery rate (84.6%, 95% CI 64.0–94.4, Q = 109.3, 4 studies) compared with those with FEP (34.4%, 95% CI 25.2–44.9, Q = 527.0, 19 studies) and schizophrenia (30.3%, 95% CI 19.7–43.6, Q = 514.7, 12 studies) (P = 0.0031).

Moderating factors

Full details of the moderators of recovery are presented in online Table DS5. Briefly, the meta-regression analyses showed that higher rates of recovery were moderated by White ethnicity (β = 0.02, 95% CI 0.01–0.04, P = 0.002, R 2 = 0.41), whereas lower rates of recovery were moderated by Asian ethnicity (β = −0.02, 95% CI −0.04 to 0.00, P = 0.019, R 2 = 0.32) and a higher loss to attrition (or drop-out rate) (β = −0.04, 95% CI −0.07 to −0.01, P = 0.009, R 2 = 0.21).

Discussion

We found that 58% of patients with FEP met criteria for remission and 38% met criteria for recovery over mean follow-up periods of 5.5 years and 7.2 years respectively. Thirty per cent of those with first-episode schizophrenia met the criteria for recovery. Our findings are particularly relevant given the previously reported lower rate of recovery in multi-episode schizophrenia of 13%. Reference Jaaskeläinen, Juola, Hirvonen, McGrath, Saha and Isohanni9 The duration of follow-up adds further weight to the significance of our findings.

Remission

Our findings for remission were remarkably stable and did not differ dependent on the use of more stringent criteria such as the RSWG (57%) or the use of broader criteria (59%). Our remission rate of 57% based on studies using the RSWG criteria is higher than the rate of 40% identified in a systematic review from 2012. Reference AlAqeel and Margolese6 Our study improves on this previous review by the inclusion of 25 studies using the RSWG criteria to define remission (compared with 12 studies) and by having a longer average duration of follow-up. Few variables were found to be moderators of remission rates, and no patient-level clinical or demographic variable was associated with remission. We identified that a more recent study period was associated with improved remission rates, perhaps reflecting the improved outcomes from patients with FEP treated in dedicated early intervention services over the past two decades.

Recovery

Our identified rate of recovery of 38% in FEP is higher than previously identified rates of 13.5% and 11–33% in multi-episode schizophrenia. Reference Warner5,Reference Jaaskeläinen, Juola, Hirvonen, McGrath, Saha and Isohanni9 Our imputed recovery rate of 23% based on the worst-case scenario technique is equivalent to the recovery rate reported by studies that defined recovery in terms of symptomatic and functional improvement sustained for more than 2 years. Further, this worst-case scenario recovery rate of 23% remains higher than that identified in the most recent review of multi-episode schizophrenia outcomes by Jääskeläinen et al. Reference Jaaskeläinen, Juola, Hirvonen, McGrath, Saha and Isohanni9 Our pooled recovery rate is similar to the 42% who showed functional recovery in the systematic review of outcome in FEP by Menezes et al, Reference Menezes, Arenovich and Zipursky7 although this ‘good’ outcome was based on data from 11 studies only, whereas we included 39 studies with recovery as an outcome. Further, in the review by Menezes et al, the ‘good’ outcome measure was based on an average follow-up period of 3 years, much shorter than our 7-year follow-up. In our review we reported on studies with standardised definitions of recovery and comparisons between those with strict and broad definitions of recovery – in contrast to the Menezes et al review, in which studies reporting on a wide variety of outcome measures (including some with definitions of remission and recovery) were combined into good, intermediate and poor outcomes. Reference Menezes, Arenovich and Zipursky7

One interesting finding is the significantly increased pooled prevalence of recovery identified in North America (Canada and USA) compared with all other regions. This regional variation in recovery was not accounted for by statistically significant differences in baseline clinical and demographic variables or drop-out rates. We identified that none of the North American studies used the more conservative 2-year criterion to define recovery, compared with eight (32%) studies from other regions, and only one (11%) North American study had a follow-up duration longer than 6 years, compared with 52% (13 studies) from other regions – differences that trended towards significance and potentially affected the improved recovery rate from this region. This finding warrants further investigation. It may be related to differences in the types of patients with FEP who were enrolled in North America compared with other regions. There may be other service-level confounds that we were unable to investigate, such as a greater proportion of studies in North America occurring in academic centres, in which more intensive and multimodal treatment approaches might have been available. However, we were unable to assess the effects of regional treatment variations that might have contributed to improved recovery rates in North America. Further, the influence of potentially non-representative sampling in this region could not be accounted for. Reference Drake and Latimer97 However, the recovery rates for studies from North America remained higher than those reported from other regions across the study periods, suggesting that the findings may not be related to health service developments.

We demonstrated for the first time in a large-scale meta-analysis that recovery in FEP is not reduced with a longer duration of follow-up. This finding, contrary to one of our hypotheses, was interesting in that those with a follow-up period greater than 6 years (32% recovery rate) and those with a 2–6 year follow-up (32% recovery rate) had equivalent rates of recovery, indicating that the rate of recovery seen from 2–6 years can be maintained for patients followed up beyond 6 years. This is in contrast to previous reviews that found an association between longer follow-up duration and reductions in ‘good’ outcomes. Reference Menezes, Arenovich and Zipursky7,Reference Hegarty, Baldessarini, Tohen, Waternaux and Oepen8 If psychotic disorders (more specifically schizophrenia) are progressive disorders, then we might expect to see decreased recovery rates with longer periods of follow-up. The fact that we have not identified any changes in recovery rates after the first 2 years of follow-up indicates an absence of progressive deterioration. This suggests that patients with worse outcomes are apparent in the earlier stages of illness, rather than that the course of illness is progressive for the majority of patients. Reference Zipursky and Agid98 This is supported by recent evidence indicating that treatment resistance in schizophrenia is present from illness onset for the majority of those who develop a treatment-resistant course of illness. Reference Lally, Ajnakina, Di Forti, Trotta, Demjaha and Kolliakou99

We predicted that a greater proportion of patients with FEP would have recovered in recent years. However, as in earlier reviews in multi-episode patient samples (and in contrast to our findings in relation to remission rates), we did not identify that recovery rates were increasing over time. Reference Warner5,Reference Hegarty, Baldessarini, Tohen, Waternaux and Oepen8,Reference Jaaskeläinen, Juola, Hirvonen, McGrath, Saha and Isohanni9 In fact, we identified a significantly reduced pooled recovery rate for studies conducted between 1997 and 2016 (32%) compared with the pooled recovery rate of 45% for studies conducted from 1976 to 1996. This finding in a FEP population indicates that thus far the dedicated and intensive specialist care provided for patients with FEP over the past two decades has not resulted in improved recovery rates, even though remission rates improved over the same period. Knowledge of factors associated with increased recovery in FEP can help identify individuals in need of more robust interventions. However, we found few moderators of recovery in our meta-analysis. White ethnicity was associated with increased recovery, whereas Asian ethnicity was associated with lower recovery rates. Higher drop-out rates moderated lower recovery, potentially indicative of a selection bias, in that those who are well and are no longer in contact with mental health services may be disproportionately lost to follow-up, thus affecting the recovery rate.

Duration of untreated psychosis

A longer DUP was not a moderator of remission or recovery rates. This was a secondary outcome measure in our study, but despite that, our findings are contrary to previous meta-analyses, which found that a shorter duration is associated with better outcomes. Reference Marshall, Lewis, Lockwood, Drake, Jones and Croudace100 Although this finding is unexpected, it is important to highlight that we did not design our study to identify all FEP studies that have investigated DUP in relation to outcomes. Further, we did not screen studies for inclusion based on definitions of DUP, potentially introducing methodological variation, and confounding the finding. It may also be probable that patients with a longer DUP might be more likely to be lost to follow-up, something that we did not control for. However, we included nine remission studies reporting on associations between mean duration of DUP and remission, similar to the ten studies included in a 2014 systematic review and meta-correlation analysis which identified a weak negative correlation between longer mean DUP and remission. Reference Penttila, Jaaskelainen, Hirvonen, Isohanni and Miettunen101

Strengths and limitations

There was considerable methodological heterogeneity across studies. Consequently, we encountered high levels of statistical heterogeneity, which is to be expected when meta-analysing observational data. Reference Stroup, Berlin, Morton, Olkin, Williamson and Rennie15 We followed best practice in conducting subgroup and meta-regression analyses to explore potential sources of heterogeneity. However, the main results do not appear to be influenced by publication bias, and were largely unaltered after applying the trim and fill method. Further, for remission there was little variability in the overall rates of remission categorised by definition of remission, study type and method of assessment used. Although the different definitions of recovery can provide an inflated rate for this outcome, we provided data relating to studies with the most stringent criteria for recovery with symptomatic and functional recovery for more than 2 years (with an identified recovery rate of 22%). We further provided a worst-case scenario rate for remission and recovery, imputing these values based on the trial number of recruited patients, and assuming that all those lost to follow-up would not have met criteria for remission or recovery. Our findings therefore offer valid measures of remission and recovery in FEP. A second limitation is the inadequate data on important confounders such as treatments given over the course of follow-up, adherence to treatment, social functioning and symptom profile over the course of follow-up, and lifestyle factors such as alcohol and substance use, precluding the meta-analytic assessment of these factors as moderating or mediating variables. Future studies might wish to consider including data from intervention studies in FEP, to assess the influence of specific treatments and adherence to treatment on remission and recovery rates. Reference Dixon, Holoshitz and Nossel102 Third, data for this meta-analysis were extracted from baseline and follow-up points from the individual studies, with limited information available in individual studies for the period during the follow-up. Fourth, although remission and recovery rates were provided at study end-point, no information was available on those who met – and sustained – criteria for remission or recovery for the entire duration of follow-up, nor at what time point individuals met criteria for remission or recovery. The absence of such data does not allow for a more detailed description of illness trajectory. However, we have been able to delineate the effects of duration of study follow-up on remission and recovery. Fifth, although we identified studies from six regions of the world, there was marked variability in the number of studies from each region, with the majority of studies conducted in North America and Europe. In relation to the higher rate of recovery identified in North America compared with other regions, we cannot rule out confounding variables relating to differences in the types of patients with FEP who were enrolled in North America compared with other regions, and other service-level confounds that might have existed between regions. However, our finding of lower remission rates in Europe is consistent with findings from the prospective Worldwide Schizophrenia Outpatient Health Outcomes study on the outcome for multi-episode schizophrenia in an out-patient setting. Reference Haro, Novick, Bertsch, Karagianis, Dossenbach and Jones103

Finally, consideration of sampling bias due to variability at the point of recruitment is required. Some patients might recover quickly from an episode and not wish to participate, others might be severely unwell and unable to consent to participate, and community-based FEP studies might be unable to recruit patients with more chaotic presentations.

Clinical implications

This is the first meta-analysis of remission and recovery rates, and moderators of these outcomes, in people with FEP, and the first meta-analysis pooling and comparing all available data across patients with FEP, first-episode schizophrenia and first-episode affective psychosis. We provide evidence of higher than expected rates of remission and recovery in FEP. We confirm that recovery rates stabilise after the first 2 years of illness, suggesting that psychosis is not a progressively deteriorating illness state. Although remission rates have improved over time rates of recovery have not done so, potentially indicating that specialised FEP services in their current incarnation have not provided improved longer-term recovery rates. Our study highlights a better long-term prognosis in FEP and first-episode schizophrenia, and a more positive outlook for people diagnosed with these conditions, than has been suggested by previous studies, which included patients with multi-episode schizophrenia.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.