Introduction

Suicide is increasingly being perceived as a complex phenomenon that appears to be the consequence of interactions between multiple psychological, biological, and social factors. It has been shown that people tend to underreport suicidal ideation [Reference Levi-Belz, Gavish-Marom, Barzilay, Apter, Carli and Hoven1], and most of the suicide attempters deny experiencing suicidal ideation when asked by healthcare providers [Reference Louzon, Bossarte, McCarthy and Katz2]. Moreover, it has been estimated that more than 50% of suicide decedents saw a health provider within a month before committing suicide [Reference Chang, Gitlin and Patel3, Reference Luoma, Martin and Pearson4]. These observations indicate the necessity to improve our understanding of processes leading to suicide in order to develop effective prevention strategies.

To date, a number of theoretical models of suicide have been proposed (for review, see [Reference Michel5]). These include the diathesis–stress model [Reference Mann, Waternaux, Haas and Malone6, Reference Mann and Rizk7], the biopsychosocial model [Reference Turecki, Brent, Gunnell, O’Connor, Oquendo and Pirkis8], the integrated motivational–volitional model [Reference O’Connor9], the interpersonal theory of suicide [Reference Van Orden, Witte, Cukrowicz, Braithwaite, Selby and Joiner10], and the narrative crisis model [Reference Galynker, Yaseen, Cohen, Benhamou, Hawes and Briggs11]. Some authors argue that suicide risk models inform about mid-term or long-term risk but not about the risk in a short-term perspective, for example, within days or hours [Reference Michel5, Reference Bryan and Rudd12]. Consequently, there are attempts that aim to shift from simple risk stratification to dynamic planning of interventions. For instance, it has recently been proposed to reformulate suicide risk stratification through the assessment of risk status (individual risk relative to specific subpopulation), risk state (individual risk with respect to baseline assessment or other time points), available resources (internal and social strengths that can support the individual in crisis), and foreseeable changes (circumstances that can quickly increase the risk of suicide) [Reference Pisani, Murrie and Silverman13]. Nevertheless, this approach still requires the recognition of risk factors in order to offer specific interventions.

There are certain suicide risk models, for example, the narrative crisis model [Reference Galynker, Yaseen, Cohen, Benhamou, Hawes and Briggs11] and the biopsychosocial model [Reference Turecki, Brent, Gunnell, O’Connor, Oquendo and Pirkis8], that posit the necessity to dissect distal risk factors (also known as long-term factors) and proximal risk factors (also known as acute risk factors) in order to better understand the development of suicidal ideation. Distal risk factors are pre-existing vulnerabilities that may facilitate suicidal ideation or behavior [Reference Cohen, Ardalan, Yaseen and Galynker14]. Most frequently, previous studies have shown that the following distal risk factors are associated with suicidal ideation: past suicidal attempts [Reference Borges, Angst, Nock, Ruscio, Walters and Kessler15], a history of mental illness [Reference Nock, Hwang, Sampson and Kessler16], especially schizophrenia spectrum psychosis [Reference Chapman, Mullin, Ryan, Kuffel, Nielssen and Large17] and recurrent depressive episodes related to major depressive and bipolar disorder [Reference Oquendo, Currier and Mann18], a history of childhood trauma (CT) [Reference King and Merchant19] with sexual abuse playing a significant role [Reference Liu, Wang, Yang, Guo and Yin20, Reference Yoon, Cederbaum and Schwartz21], a history of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) [Reference Chan, Bhatti, Meader, Stockton, Evans and O’Connor22, Reference Koenig, Brunner, Fischer-Waldschmidt, Parzer, Plener and Park23], parental death by suicide, parental mental illness, and parental antisocial personality disorder [Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Hwang, Chiu, Kessler and Sampson24]. On the other side, there are several proximal risk factors indicative of an imminent suicide risk identified, including substance use [Reference Glenn and Nock25], negative interpersonal events [Reference Bagge, Glenn and Lee26], negative affective states, such as intense anxiety or agitation [Reference Busch, Fawcett and Jacobs27], insomnia [Reference Pigeon, Pinquart and Conner28], current mental disorders [Reference Favril, Yu, Uyar, Sharpe and Fazel29] as well as physical suffering [Reference Ratcliffe, Enns, Belik and Sareen30]. Among them, recent studies highlight the role of psychotic-like experiences (PLEs) that are characterized by low severity, persistence, or associated functional impairment, and thus cannot be the basis to diagnose mental disorders according to international diagnostic systems [Reference Kelleher and Cannon31–Reference Yates, Lang, Cederlof, Boland, Taylor and Cannon33]. Primarily, PLEs have been considered to serve as a risk factor of psychotic disorders; however, there is accumulating evidence that their occurrence might also predict the development of other mental disorders [Reference Lindgren, Numminen, Holm, Therman and Tuulio-Henriksson34]. Nevertheless, several studies have shown that PLEs are associated with increased suicide risk [Reference Karcher, O’Hare, Jay and Grattan32, Reference Yates, Lang, Cederlof, Boland, Taylor and Cannon33, Reference DeVylder, Thompson, Reeves and Schiffman35]. Although distal risk factors may indicate individuals who are more likely to have suicidal thoughts and engage in suicidal behavior in their lifetime, proximal risk factors are indicative of individuals with increased intensity of short-term suicidal ideation and a higher likelihood to act on their suicidal thoughts [Reference Bagge, Glenn and Lee26].

There are studies showing that assessment of distal and proximal risk factors might serve as a valid empirical model of progression from chronic to near-term suicidal risk. These studies clearly indicate that pre-existing neurodevelopmental vulnerabilities, including, for example, CT history, trait impulsivity, and perfectionism might interact with proximal factors, for example, suicidal narratives, fear of humiliation, recent life stressors in shaping near-term suicidal risk [Reference Cohen, Mokhtar, Richards, Hernandez, Bloch-Elkouby and Galynker36, Reference Bloch-Elkouby, Gorman, Lloveras, Wilkerson, Schuck and Barzilay37]. However, there is accumulating evidence that other neurodevelopmental vulnerabilities, for example, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms and specific learning disabilities may also serve as prerequisites of trajectories leading to suicide. Indeed, recent meta-analyses found that a diagnosis of ADHD is associated with increased risk of suicidal ideation, plans and attempts as well as completed suicide [Reference Septier, Stordeur, Zhang, Delorme and Cortese38, Reference Bartoli, Callovini, Cavaleri, Cioni, Bachi and Calabrese39]. Also, it has been found that specific learning disorders, including reading disabilities (RDs), are associated with higher risk of suicidal attempts after adjustment for known risk factors, for example, CT, a history of mental disorders and substance abuse [Reference Fuller-Thomson, Carroll and Yang40]. Nevertheless, specific mechanisms linking these neurodevelopmental vulnerabilities with suicide risk remain unknown. Moreover, their assessment in suicide risk models addressing interactions between proximal and distal risk factors has not been performed so far. Taking into consideration these research gaps in the field, we aimed to investigate the association of the interplay between distal (symptoms of ADHD, RD, CT history, and lifetime history of NSSI) and proximal factors (depressive symptoms, PLEs, and insomnia) with the current suicidal ideation in a nonclinical population.

Methods

Participants

The snowball sampling method was used to recruit participants. All questionnaires were administered through the computer-assisted web interview. The survey was posted in social media and survey websites between April and October, 2022. Participants were informed about confidentiality and anonymous character of the survey. All of them represented inhabitants of three large Polish cities, including Szczecin, Warsaw, and Wroclaw. They were included in case of meeting two inclusion criteria, that is, age between 18 and 35 years and a negative lifetime history of psychiatric treatment. The results of the present study are part of a bigger project addressing epigenetic mechanisms of psychosis proneness. The protocol of the study was approved by the Ethics Committees at the Institute of Psychology (Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw, Poland, approval number: 16/VII/2022), Wroclaw Medical University (Wroclaw, Poland, approval number: 129/2022), and Pomeranian Medical University (Szczecin, Poland, approval number: KB-006/25/2022).

Assessments

Childhood trauma

A history of four categories of CT (under the age of 17 years), including emotional abuse and neglect, physical abuse as well as sexual abuse was recorded. To obtain information about emotional neglect and abuse, as well as bullying we used three items of the Traumatic Experience Checklist (TEC) [Reference Nijenhuis, Van der Hart and Kruger41]. Additionally, three items were selected from the Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse Questionnaire (CECA.Q) to record exposure to sexual abuse [Reference Bifulco, Bernazzani, Moran and Jacobs42]. A detailed description of all items is reported in Supplementary Material.

Assessment of RD

The Adult Reading Questionnaire (ARQ) was used to assess the severity of RD [Reference Snowling, Dawes, Nash and Hulme43]. The ARQ is a 15-item self-report that includes seven items investigating literacy skills, word-finding abilities, and organization, two items measuring self-appraisal of general reading abilities, two items measuring the frequency or reading and writing, and four items about a diagnosis of dyslexia. The total ARQ score ranges between 0 and 43. Higher ARQ scores indicate worse reading abilities. The Cronbach’s alpha of the ARQ was 0.660 in our sample.

Screening of ADHD

The Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) was used to assess ADHD symptoms. It is a self-report questionnaire with nine items measuring inattention and nine items measuring impulsivity/hyperactivity over the period of the preceding 6 months [Reference Kessler, Adler, Gruber, Sarawate, Spencer and Van Brunt44]. Each item refers to the frequency of specific symptoms on a five-point scale (0—“never” to 4—“very often”). The total score ranges between 0 and 64. The Cronbach’s alpha of the ASRS was 0.819 in our sample.

PLEs

For the purpose of this study, we developed a 16-item questionnaire that records the presence of PLEs during the preceding month. Participants were asked to assess the presence of specific PLEs that cannot be attributed to substance use on a four-point scale (1—“never”; 2—“sometimes”; 3—“often”; and 4—“almost always”). Specific items were obtained from the following questionnaires (for the content of specific items, see Supplementary Material): (a) the Revised Hallucination Scale [Reference Gaweda and Kokoszka45–Reference Morrison, Wells and Nothard47] (three items); (b) the Revised Green et al., Paranoid Thoughts Scale [Reference Freeman, Loe, Kingdon, Startup, Molodynski and Rosebrock48] (four items); and (c) the Prodromal Questionnaire [Reference Ising, Veling, Loewy, Rietveld, Rietdijk and Dragt49] (nine items). The total score of the questionnaire ranges between 16 and 64 points. The Cronbach’s alpha of the questionnaire was 0.784 in our sample.

Depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and NSSI

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) was administered to measure the level of depressive symptoms [Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams50]. It includes nine questions about the frequency of specific depressive symptoms over the preceding 2 weeks that are scored on a four-point scale (from 0—“not at all” to 3—“nearly every day”). The Cronbach’s alpha of the PHQ-9 was 0.763 in our sample. The last item: “thoughts that you would be better off dead, or of hurting yourself in some way?” was used to analyze the current suicidal ideation. Participants who scored at least 1 point on this item were classified as those experiencing current suicidal ideation. In turn, a lifetime history of non-suicidal ideation was assessed using one item from the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory (DSHI) [Reference Gratz51]: “Have you ever intentionally (i.e., on purpose) cut your wrist, arms, or other area(s) of your body (without intending to kill yourself)?”

Insomnia

The level of insomnia was assessed using four items from the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) [Reference Morin, Belleville, Belanger and Ivers52]. The ISI is based on seven questions. We used the first three items to record difficulty in falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep, and problems with waking up too early on a five-point scale (scored from 0—“none” to 4—“very severe”). The next question assessed the level of satisfaction/dissatisfaction with the current sleep pattern on a five-point scale (scored from 0—“very satisfied” to 4—“very dissatisfied”). The total score from the ISI questions used in the present study ranged between 0 and 16, with higher scores indicating greater severity of insomnia. The Cronbach’s alpha of this questionnaire was 0.705.

Data analysis

There were no missing data in the present analysis. Before performing data analysis, variables potentially associated with a risk of suicidal ideation were divided into the following groups: (a) sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, education, being married or informal relationship, and occupation); (b) distal factors (symptoms of ADHD and RD, lifetime history of NSSI and problematic substance use, family history of schizophrenia and mood disorders as well as CT history); and (c) proximal factors (depressive symptoms, insomnia, and PLEs). Symptoms of ADHD and RD were included as distal factors as they represent disorders with the onset in the early neurodevelopmental period.

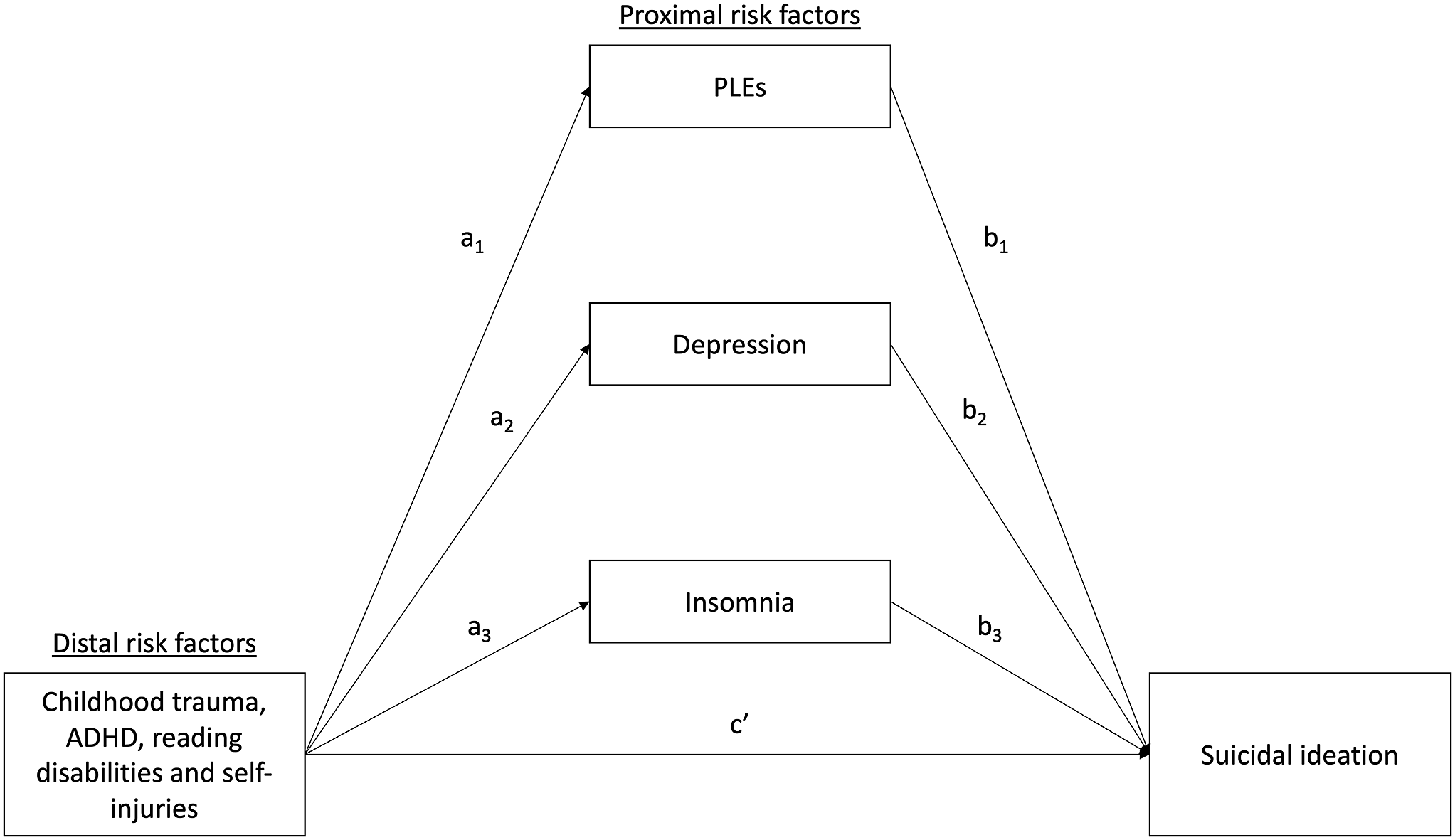

A series of bivariate comparisons of individuals with and without the current suicidal ideation were performed using the χ2 (categorical variables) or the Mann–Whitney U test (continuous variables). Next, binary logistic regression analyses were performed in a step-by-step procedure. The current suicidal ideation was included as a dependent variable. First, we tested the effects of proximal factors, distal factors, and sociodemographic characteristics as independent variables separately. Then, we combined these sets of variables in two blocks, that is, distal and proximal factors with and without sociodemographic characteristics. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test was implemented to assess the goodness of fit for logistic regression models. In this part, the results of data analysis were considered statistically significant in case of a p-value lower than 0.05. Finally, we analyzed the mediating effect of proximal factors in the association between distal factors and suicidal ideation using the PROCESS Macro (model 4) [Reference Preacher and Hayes53]. Mediation analyses were performed separately for specific distal factors (Figure 1). The results of this analysis were considered significant if 95% CI did not include zero.

Figure 1. The mediation model tested in the present study. Results of data analysis are reported in Table 3.

Results

The general characteristics of the sample

A total of 3,000 young adults were enrolled (aged 25.4 ± 4.9 years, 41.7% males). General characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. Individuals reporting suicidal ideation were significantly younger, were more likely to be females, had lower education level, reported worse occupational situation as well as were less likely to be married or in an informal relationship compared to their counterparts. Family history of schizophrenia and mood disorders, lifetime problematic substance use, exposure to any CT, as well as lifetime history of NSSI were significantly more frequent among individuals reporting suicidal ideation. Moreover, participants reporting suicidal ideation had higher levels of RD, ADHD symptoms, depression, insomnia, and PLEs.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of the sample.

Data presented as mean ± SD or n (%).

Abbreviations: ARQ, the Adult Reading Questionnaire; ASRS, the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale; CT, childhood trauma; ISI, the Insomnia Severity Index; PHQ-9; the Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PLEs, psychotic-like experiences; SI(+), participants with the current suicidal ideation; SI(−), participants without the current suicidal ideation.

Results of binary logistic regression analyses

The results of the binary logistic regression analyses are presented in Table 2. The following factors were significantly associated with a higher risk of suicidal ideation in separate blocks of independent variables: (a) sociodemographic characteristics: female gender, being single, lower level of education and being unemployed, or rent; (b) all proximal factors, that is, higher levels of PLEs, depression, and insomnia; and (c) distal factors: exposure to any CT, lifetime history of NSSI as well as higher levels of ADHD symptoms and RD. After combining all factors together, the following of them were associated with a higher risk of suicidal ideation: (a) sociodemographic characteristics: being single and being unemployed or rent; (b) all proximal factors, that is, higher levels of PLEs, depression, and insomnia; and (c) distal factors: higher levels of RD and lifetime history of NSSI.

Table 2. Results of binary logistic regression analysis.

Abbreviations: ARQ, the Adult Reading Questionnaire; ASRS, the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale; CT, childhood trauma; ISI, the Insomnia Severity Index; NSSI, non-suicidal self-injuries; PHQ-9; the Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PLEs, psychotic-like experiences.

Results of mediation analyses

The results of mediation analyses are shown in Table 3. In these analyses, we further tested the effect of distal mediators that appeared to be significantly associated with a risk of suicidal ideation in any logistic regression analysis. All direct effects of distal factors on proximal factors were significant. Also, all direct effects of proximal factors on the risk of suicidal ideation were significant. However, the direct effects of distal factors on the risk of suicidal ideation were significant only in the case of a lifetime history of NSSI and RD. In other words, the direct effects of CT history and ADHD symptoms on the risk of suicidal ideation were not significant. All indirect effects, that is, from distal factors to the risk of suicidal ideation through the effects of proximal factors, were significant. The mediation models explained 30.9–32.2% of the variance in the risk of suicidal ideation.

Table 3. Results of mediation analysis.

Covariates include age, sex, being married or in a relationship, education level, and the current occupational situation.

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; CT, childhood trauma; NSSI, non-suicidal self-injuries; RDs, reading disabilities.

Discussion

In the present study, we found that both sociodemographic factors (being unemployed, single, and male), as well as clinical characteristics (CT history, RD, ADHD, lifetime history of NSSI, PLEs, depression, and insomnia), play a role in the development of suicidal ideation. However, further analysis showed that the effects of CT history and ADHD symptoms on the risk of suicidal ideation are fully mediated by the effects of proximal factors, including PLEs, depression, and insomnia. In turn, other distal factors, including RD and NSSI may directly and indirectly (through proximal factors) increase the risk of suicidal ideation. To the best of our knowledge, this is, the first investigating potential mechanisms by which symptoms of ADHD and RD together with other distal factors interact with proximal factors represented by depressive symptoms, PLEs, and insomnia to shape the current suicidal ideation. Previous studies have investigated only some of variables that we have combined in our model providing grounds for more comprehensive analysis of the interplay and significance of proximal and distal factors.

Childhood traumatic events, especially a history of sexual or physical abuse, have been shown to cause at least a threefold increase in lifetime suicide attempts and lifetime suicidal ideation [Reference Bruffaerts, Demyttenaere, Borges, Haro, Chiu and Hwang54–Reference McHolm, MacMillan and Jamieson56]. Some studies suggest that suicidal risk is associated independently with childhood adverse experiences [Reference Bruffaerts, Demyttenaere, Borges, Haro, Chiu and Hwang54, Reference Aaltonen, Naatanen, Heikkinen, Koivisto, Baryshnikov and Karpov55, Reference Enns, Cox, Afifi, De Graaf, Ten Have and Sareen57]. However, such experiences predispose to various mental disorders, including mood, anxiety, substance use, and borderline personality disorders [Reference Afifi, Henriksen, Asmundson and Sareen58–Reference Keyes, Eaton, Krueger, McLaughlin, Wall and Grant60], all of which may act as mediators for suicidal behavior [Reference Bebbington, Cooper, Minot, Brugha, Jenkins and Meltzer61, Reference Fergusson, Woodward and Horwood62]. Moreover, childhood adversities are also associated with earlier onset and more chronic course of mental disorders [Reference Etain, Aas, Andreassen, Lorentzen, Dieset and Gard63, Reference Nanni, Uher and Danese64]. Thus, controlling for various dimensions of symptomatology and examining causal pathways as well as possible indirect effects between CT and suicidality can yield reliable results. This is in line with other studies showing that psychopathology associated with childhood adversities partially [Reference Park, Hong, Jeon, Seong and Cho65] or fully [Reference Martin, Bergen, Richardson, Roeger and Allison66, Reference Zhou, Luo, Wang, Zhu, Wu and Sun67] mediates the relationship between exposure to CT and suicidal ideation or attempts.

In our study, we found that CT history is associated with the risk of suicidal thoughts through the mediating effect of the severity of PLEs, depression, and insomnia. This is in agreement with previous studies, showing that PLEs increase the risk of suicide [Reference Nishida, Shimodera, Sasaki, Richards, Hatch and Yamasaki68–Reference Bromet, Nock, Saha, Lim, Aguilar-Gaxiola and Al-Hamzawi70]. Moreover, in the longitudinal perspective, baseline severity of PLEs has been observed to predict the worsening of suicidal ideation and behavior over time [Reference Karcher, O’Hare, Jay and Grattan32]. Also, associations of delusional ideation and perceptual distortions with suicidality have been observed to be stronger with time and more pronounced in comparison to general psychopathology [Reference Karcher, O’Hare, Jay and Grattan32]. Similar to our results, it has been shown that PLEs are predictive of suicidal thoughts, even when controlling for sociodemographic variables and traumatic experiences [Reference Jay, Schiffman, Grattan, O’Hare, Klaunig and DeVylder71]. Additionally, a history of childhood adversities, such as peer bullying, poverty, and left-behind status, has been found to increase suicide risk through the mediating effect of PLEs [Reference Li, Hu and Tang72]. In line with our findings, depressive symptomatology has been associated with a history of CT and suicidality [Reference Rotenstein, Ramos, Torre, Segal, Peluso and Guille73], and might mediate the relationship between a history of CT and suicidal risk [Reference Martin, Bergen, Richardson, Roeger and Allison66, Reference Gaweda, Pionke, Krezolek, Frydecka, Nelson and Cechnicki74]. Early-life stressors have also been demonstrated to alter sleep regulation, leading to life-long sleep disturbances, including insomnia [Reference Lo Martire, Caruso, Palagini, Zoccoli and Bastianini75]. On the other site, insomnia has been shown to play a role in dysregulating the systems involved in mood and emotion regulation, thus influencing the onset and maintenance of depressive symptomatology [Reference Palagini, Geoffroy, Miniati, Perugi, Biggio and Marazziti76]. Insomnia has also been demonstrated to play an important role in the relationship between early-life stressors and depression, thereby influencing the risk of suicidal ideation [Reference Palagini, Miniati, Marazziti, Sharma and Riemann77].

Our results on the significance of the association between ADHD symptoms and the risk of suicidal ideation are in line with a recent systematic review and meta-analysis [Reference Liu, Walsh, Sheehan, Cheek and Sanzari78]. Moreover, we observed that the relationship between ADHD symptoms and suicidality is fully mediated through proximal factors—PLEs, depression, and insomnia. Follow-up studies of ADHD children into adolescence, as well as early adulthood, indicate that the symptoms of ADHD frequently persist and are associated with various types of psychopathology and dysfunction in later life [Reference Wilens, Biederman and Spencer79]. It has been demonstrated that the majority of individuals with ADHD experience at least one comorbid mental disorder [Reference Sobanski, Bruggemann, Alm, Kern, Deschner and Schubert80]. The results of our study are in agreement with numerous reports showing that the association between ADHD traits and suicidality is fully mediated by the presence of comorbid mental disorders. This has been shown both with respect to the current [Reference Arsandaux, Orri, Tournier, Gbessemehlan, Cote and Salamon81, Reference Balazs, Miklosi, Kereszteny, Dallos and Gadoros82] as well as lifetime suicidal ideation [Reference Zhong, Lu, Wilson, Wang, Duan and Ou83]. Some studies suggest that symptoms of ADHD, such as inattention, impulsivity or executive dysfunction, serve as an independent risk factor for suicidality [Reference Keilp, Gorlyn, Russell, Oquendo, Burke and Harkavy-Friedman84–Reference Wang, He, Yu, Qiu, Yang and Qiao86]. However, these traits have been found to mainly predict suicide attempts and to a much lesser extent, suicidal ideation [Reference Wang, He, Yu, Qiu, Yang and Qiao86]. Nevertheless, some studies have observed direct associations of ADHD with suicidality after controlling for comorbid psychiatric disorders [Reference Brown, McLafferty, O’Neill, McHugh, Ward and McBride87–Reference Eddy, Eadeh, Breaux and Langberg89]. To the best of our knowledge, none of the previous studies has tested the mediating effect of PLEs in the association between ADHD symptoms and suicidality. However, one study revealed the moderating effect of emotion dysregulation and impulsivity on the relationship between PLEs and suicidal ideation in children [Reference Grattan, Karcher, Maguire, Hatch, Barch and Niendam90].

In our study, we found that RD are directly and indirectly associated with the risk of suicidal ideation. Dyslexia is a developmental disability characterized by difficulties in reading comprehension and writing without overall sensory or intelligence deficits [Reference Ferrer, Shaywitz, Holahan, Marchione and Shaywitz91]. Accumulating evidence shows that individuals with dyslexia are at greater risk of developing numerous psychological [Reference Sahoo, Biswas and Padhy92] and psychiatric [Reference Willcutt and Pennington93] comorbidities. They have the tendency to report lower self-esteem and self-concept, aggressiveness and rule-breaking behaviors, problems in social interactions, as well as higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms, fatigue, and sleeping difficulties in comparison with their peers without RD [Reference Parhiala, Torppa, Eklund, Aro, Poikkeus and Heikkila94, Reference Giovagnoli, Mandolesi, Magri, Gualtieri, Fabbri and Tossani95]. However, there is a scarcity of studies showing the association between RD and suicidality. It has been demonstrated that children with dyslexia report more suicidal ideation compared to children without RD [Reference de Lima, Salgado-Azoni, Dell’Agli, Baptista and Ciasca96], and adolescents with poor reading abilities might be more likely to experience suicidal ideations or attempts, even after controlling for sociodemographic factors and psychiatric comorbidity [Reference Daniel, Walsh, Goldston, Arnold, Reboussin and Wood97]. Additionally, the analysis of a broader range of learning disabilities, including impairments of various functional and academic skills, has revealed their association with a higher risk of suicidal ideation and behaviors [Reference Svetaz, Ireland and Blum98, Reference Wilson, Deri Armstrong, Furrie and Walcot99].

Another observation from our study is that the lifetime history of NSSI is directly and indirectly associated with the risk of suicidal ideation. Importantly, logistic regression analysis revealed that lifetime history of NSSI was associated with about twofold higher risk of suicidal ideation, and this magnitude of the effect was the highest among all potential correlates analyzed in the present study. By definition, NSSI describes deliberate behaviors that inflict pain and/or cause damage to the body without suicidal intent [Reference Klonsky100]. It has been shown that NSSI might be characterized by a variety of inter- and intrapersonal purposes, mainly emotion regulation, communicating distress or influencing behavior of other people [Reference Taylor, Jomar, Dhingra, Forrester, Shahmalak and Dickson101]. There are numerous studies showing the relationship between NSSI and the increased likelihood of suicide ideation and attempts [Reference Muehlenkamp and Brausch102–Reference Griep and MacKinnon104]. A recent meta-analysis estimated the risk of fatal outcomes of NSSI at 1.3% within 1 year; however, this risk appeared to be almost threefold higher in a 3-year follow-up [Reference Liu, Lunde, Jia and Qin105]. Also, it has been found that the increased risk of suicide following NSSI in longitudinal studies is associated with male gender, multiple episodes of NSSI, a diagnosis of psychiatric disorder, and physical illness [Reference Liu, Jia, Qin, Zhang, Yu and Luo106]. It has been suggested that the relationship between NSSI and increased suicidal risk can be explained by the acquired capability for suicide, whereby repetitive exposure to emotionally provocative and physically painful events results in increased tolerance to pain and decreased fear of death [Reference Willoughby, Heffer and Hamza107]. The results of our study are in line with reports showing the association of NSSI with PLEs and depressive symptomatology [Reference Nishida, Sasaki, Nishimura, Tanii, Hara and Inoue108, Reference Lee, Kim, Kim, Kim, Shin and Kim109], which in turn are linked to increased risk of suicidal ideations and behaviors [Reference Nishida, Shimodera, Sasaki, Richards, Hatch and Yamasaki68, Reference Jay, Schiffman, Grattan, O’Hare, Klaunig and DeVylder71].

The results of our study should be interpreted bearing in mind several limitations. First, internet-based surveys can be characterized by a variety of limitations related to insufficient accuracy of self-reports, difficulties in tracking non-response rates and a selection bias [Reference Wright110, Reference Riboldi, Crocamo, Callovini, Capogrosso, Piacenti and Calabrese111]. Second, the cross-sectional design limits the possibility of concluding about firm causal inferences. Third, recall biases may exist with respect to assessments of childhood maltreatment, especially in the presence of depressive symptoms and PLEs. Fourth, although assessments in our study included an extensive set of potential factors, the percentage of variance in suicidal ideation explained by our models was limited, suggesting the importance of other mechanisms and factors that were not recorded. Fifth, the results of the present study should be interpreted with caution due to the use of a nonclinical sample and selected items from assessment tools. Therefore, generalization of findings over the clinical population of patients with dyslexia or ADHD should be approached cautiously. At this point, it is also important to note that assessment of suicidal ideation was limited to the use of one item from the PHQ-9. However, there are studies showing the usefulness of this item in stratifying the risk of suicide attempt [Reference Louzon, Bossarte, McCarthy and Katz2, Reference Penfold, Whiteside, Johnson, Stewart, Oliver and Shortreed112, Reference Uebelacker, German, Gaudiano and Miller113]. Finally, our sample was limited to young adults, and thus generalization to other populations should be approached cautiously.

In sum, the findings of this study demonstrate that the risk of suicide ideation is associated with the interplay of distal (CT, ADHD symptoms, RD, and self-injuries) and proximal factors (PLEs, depression, and insomnia). Longitudinal studies in clinical samples are needed to confirm our findings before their translation into clinical practice. Nevertheless, implications from the present study suggest that patients with neurodevelopmental disorders should be carefully assessed for their suicidal risk, and the current psychiatric symptoms should be treated accordingly in order to decrease the risk of suicidal behaviors.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2023.14.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in the present study are available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) database (https://osf.io/8ju6b/).

Author Contributions

Design and conduct of the study: B.M., Ł.G., J.S.; Collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data: B.M., D.F.; Preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript: B.M., Ł.G., J.S., D.F.; Decision to submit the manuscript for publication: B.M., Ł.G., J.S., D.F.

Financial Support

This research was funded in whole or in part by National Science Centre, Poland (Grant Number: 2021/41/B/HS6/02323). For the purpose of Open Access, the authors have applied a CC-BY public copyright license to any Author Accepted Manuscript (AAM) version arising from this submission.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare none.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.