1 Introduction

The relationship between science and law has generated long-lasting dilemmas in scholarship. In particular, the impact of ‘bad’ science on judicial decision-making remains a thorny subject. This paper explores two controversial Italian judgments using a combination of actor–network theory (ANT) and legal pragmatism, revealing a network of actors contributing to a particular unfolding of events. Because this study focuses on complex interactions between discrete (and at times distant) actors, it can provide useful lessons for legal systems grappling with contested public health matters.

In 2017, the Italian parliament legislated to make ten childhood vaccines mandatory.Footnote 1 This measure followed a drop in immunisation rates over the preceding years. Two judicial decisions – from the Tribunals of Rimini in 2012 and Milan in 2014Footnote 2 – punctuated this negative trend. In both judgments, courts sanctioned the existence of a causal link between childhood vaccines and autism.

Multidisciplinary studies conducted by social scientists, epidemiologists and behavioural economists have showed noticeable correlations between these decisions and increased online interest in ‘no-vax’ theories, with corresponding drops in immunisation rates in Italy (Attwell et al., Reference Attwell2018). Indeed, national immunisation rates decreased steadily between 2013 through to 2015 (Attwell et al., Reference Attwell2018; Giambi et al., Reference Giambi2018; Aquino et al., Reference Aquino2017). The viral spread of misinformation following the Rimini decision arguably ‘resulted in a decrease in child immunization rates for all types of vaccines’ (Carrieri et al., Reference Carrieri, Madio and Principe2019, p. 1377). We do not claim an exhaustive causal relationship between the decisions and decreasing immunisation rates. On the contrary, we see these cases as part of a varied network including insufficient awareness of individual and collective benefits of vaccines, the diffusion of ‘fake news’ on correlations between vaccines and autism, a corresponding traction of ‘no-vax’ theories and movements (Ministry of Health, 2017) and a parallel governmental inability to react (Attwell et al., Reference Attwell2021). Yet, the recognised impact of both decisions prompts us to treat them as intrinsically worthy of a dedicated case-study (Baxter and Jack, Reference Baxter and Jack2008).

This paper is structured as follows. We begin by delineating our approach and research design. We then offer a thorough account of the Rimini and Milan decisions, and subsequently interrogate the interactions that enabled them. We dissect the legal processes as well as the broader context of decision-making and interactive practices within and between relevant actors and institutions. We also consider broader awareness of societal sensitivities within relevant institutions. Finally, we present the impact of these decisions on the governance of vaccine acceptance in Italy, and specifically for situations involving complex scientific evidence and socially value-laden merits.

2 Approach, methods and materials

2.1 Theoretical and methodological background

The Rimini and Milan decisions triggered significant debate in Italian legal scholarship. Several studies discussed the ambiguity of ‘proof’ in Italian civil litigation (Nocco, Reference Nocco2014) and the permissive nature of the causal inquiry (Breda, Reference Breda2018; Parziale, Reference Parziale2017). The decisions are also interrogated in international scholarship (Rajneri, 2018), focusing on the challenges of inferential proof of causation in litigation involving scientific matters in civil-law jurisdictions (Rizzi, Reference Rizzi2018).

This study offers a broader socio-legal analysis that puts the two decisions in context, providing a framework to understand their dynamics and significance by reconciling an internal point of view (relevant legal actors, institutions and instruments) with an external one (the socio-political context of decision-making and the agency of actors involved). This combination broadly situates this study within the idea of legal pragmatism (Cometti, Reference Cometti2010; Lazaro, Reference Lazaro2016).

We approach our inquiry by adopting the basic tenet of ANT that the social is not a preset reality, but rather the product of networks emerging from interactions between objects and actors (human or non-human) (Latour, Reference Latour2007). ANT is itself a contested field, and it is beyond the scope of this paper to relitigate its different interpretations (Law, Reference Law and Turner2009). More modestly, we deploy social construction as an analytical tool to unpack the Rimini and Milan decisions and their aftermaths. Networks are the ‘summing up of interactions through various kinds of devices, inscriptions, forms and formulae, into a very local, very practical, very tiny locus’ (Latour, Reference Latour1999, p. 17, emphasis in original). This formulation is reminiscent of Law's original observation of networks as a combination of ‘documents, devices and people’ (Law, Reference Law and Law1986, p. 254). As observed by Cowan and Carr, ‘participants in such networks are active mediators … as opposed to passive intermediaries’ (2008, p. 152) who mould reality and the social ‘making it bifurcate in unexpected ways’ (Latour, Reference Latour2007, p. 202). This study traces unexpected bifurcations within the social realm as law interacts with science (Jasanoff, Reference Jasanoff1995) in a socially contested field. In observance with the broad methodological requirement of ANT, we ‘follow the actors in their weaving through things’ (Latour, Reference Latour2007, p. 68) to emerge with a rich tapestry of interactions and dynamics leading up to, and resulting from, our case-studies. We acknowledge that, in doing so, we are principally adopting ANT as a methodological framework.

One recognised limitation of ANT is the artificial neutrality of analytical starting points that is presumed in merely ‘following the actors’ to uncover a network (the issue of ‘flat networks’) (Cloatre, Reference Cloatre2018, p. 653). This poses two potential problems, which we pre-emptively address.

First, ANT fails to recognise that pre-existing power relations influence how actors ‘weave through things’. We do not dispute the inherently value-laden nature of law, which indubitably crystallises power relations, and we accordingly maintain a pragmatist distinction between an internal point of view, focused on the intrinsically legal dimensions of the decisions, and an external vantage point, incorporating exogenous factors that influence their happening and aftermaths. We therefore use ANT as a ‘toolbox’ to unpack the ‘silent ways in which law may work through the travels of materials that are already loaded with meaning’, such as disproved scientific theses (Cloatre, Reference Cloatre2018, p. 657).

The second problem is that ANT can fail to recognise the inevitable biases of the observer. This is the problem of positionality, developed by critical feminist and post-colonial scholars (Anderson, Reference Anderson2002; Haraway, Reference Haraway1988). We acknowledge that any vision, including our own, is inherently ‘embodied’, and to this study we bring positionalities as vaccination law, social science and medical experts. We recognise that vaccine hesitancy is complex and multi-faceted (Dubé et al., Reference Dubé, Vivion and MacDonald2015) and that vaccine-refusing families believe that they are considering their children's best interests (Ward et al., Reference Ward2017), and we distinguish between such parents and the anti-vaccination (or ‘no-vax’ in Italy) theorists and movements. Crucially, we maintain a vivid analytical interest for the multiple lives that given theories can have in the scientific community as opposed to the socio-legal arena. However, we do adhere to a binary framing in recognising anti-vaccination evidence as fallacious based on established scientific consensus.

In this regard, we adopt the term ‘zombie idea’ to characterise the proposition that a link exists between autism and childhood vaccines. This thesis, developed in the 1990s by Andrew Wakefield with reference to the combination MMR vaccine (Wakefield et al., Reference Wakefield1998), has been comprehensively disproved by the scientific community and was retracted by the medical journal The Lancet in 2010 (Editors of The Lancet, 2010). Yet, in 2012 and 2014, in Rimini and Milan, courts and experts relied on this study. In the 1990s, American scholars coined the term ‘junk science’ to capture what they saw as a major factor in lengthy and unproductive litigation, irrational decision-making and overall ‘failure of traditional “gatekeeping processes” … for the admissibility of expert evidence’ (Edmond and Mercer, Reference Edmond and Mercer1998, p. 4; Bernstein, Reference Bernstein1996; Huber, Reference Huber1991). Science and Technology Studies (STS) have since vigorously criticised the concept of ‘junk science’ as concealing an agenda aimed at creating politically motivated benchmarks for ‘good’ and ‘bad’ science (Edmond and Mercer, Reference Edmond and Mercer1997; Reference Edmond and Mercer1998).

We do not engage with the process of evaluating scientific evidence in this study. Again, we assume the validity of findings that no links exist between autism and childhood vaccines, and from this standpoint we interrogate evidence to that effect in court judgments. The journalistic term ‘zombie idea’ thus befits our purposes as it describes ‘ideas that keep being killed by evidence, but nonetheless shamble relentlessly forward, essentially because they suit a political agenda’ (Krugman, Reference Krugman2012). The ‘parallel’ lives of Wakefield's ideas in science, law and society provide an opportunity to reflect on broader ideas of truth production and multiple ontologies, and particularly their consequences in the context of scientifically complex cases. This is very relevant at a time when societal frictions around scientific truths related to vaccination are an ongoing feature of public discourse (Islam et al., Reference Islam2021).

Methodologically, this study is constructivist (Merriam and Tsidell, Reference Merriam and Tsidell2015), combining doctrinal analysis of the Rimini and Milan decisions and other relevant legal texts with empirical data and non-legal accounts of the decisions. The combination of doctrinal and empirical methods is increasingly common in legal scholarship (Cowan and Carr, Reference Cowan and Carr2008; Hillyard, Reference Hillyard2007; McCrudden, Reference McCrudden2006) and well suited to an ANT analysis that examines complex ‘socio-legal objects’ (human and non-human) (Cloatre, Reference Cloatre2008). This study draws upon three distinct datasets: (1) primary sources; (2) key informant interviews; and (3) a systematic analysis of newspaper coverage received by the two cases. We engage with scholarly literature to provide further depth and analysis.

2.2 Primary sources

We have systematically gathered every accessible legislative, judicial or procedural document directly relevant to the two decisions. Some were publicly available, others obtained through official access to information requests.

The main publicly available primary sources were:

1 Judgment n. 1767/14 of the Court of Appeal of Bologna, Labour Controversies Section (‘Bologna appeal’) reversing the first-instance decision by the Tribunal of Rimini

2 Judgment n. 597/2018 of the Court of Appeal of Milan, Labour Section (‘Milan appeal’) reversing the first-instance decision by the Tribunal of Milan

3 Law of 25 February 1992, n. 210 on compensation for victims of irreversible damages caused by mandatory vaccination, blood transfusions and blood products (‘Law n. 210/1992’).

Our core analysis focuses on the first-instance judgments of Rimini 2012 and Milan 2014, for which we requested access to all relevant documents.Footnote 3

The Tribunal of Rimini, on 14 May 2019, authorised access to the following documents:

1 Full-text version of the Judgment n. 2010/148 of the Tribunal of Rimini, Civil Section, Labour Sector (‘Rimini decision’)

2 Full-text version of the Report filed by the court-appointed Office Technical Consultant (Barboni, Reference Barboni2012), summarising the scientific evidence submitted by the parties

3 Full-text version of the plaintiff's submission (Ventaloro, Reference Ventaloro2010)

4 Full-text version of the defendant's submission (State Attorney's Office, 2010)

5 Full-text version of the Minutes of the Hearing (Ardigò, Reference Ardigò2010).

The Tribunal of Milan, on 29 May 2019, authorised access to the following documents:

1 Full-text version of the Judgment n. 2664/2014 of the Tribunal of Milan, Labour Section (‘Milan decision’)

2 Full-text version of the report filed by the court-appointed Office Technical Consultant (Tornatore, Reference Tornatore2014), summarising the scientific evidence submitted by the parties.

There is a discrepancy in the access granted by the two courts. Tribunal presidents retain a significant degree of discretion on the level of access to trial documents that they grant to individual petitioners. As both cases involved a combination of sensitive clinical data and an injured minor, a prudent approach is unsurprising. Nevertheless, the full texts of the judgment and report contain the information necessary to conduct the case analysis of the Milan decision without compromising its rigour.

2.3 Interview with key informants

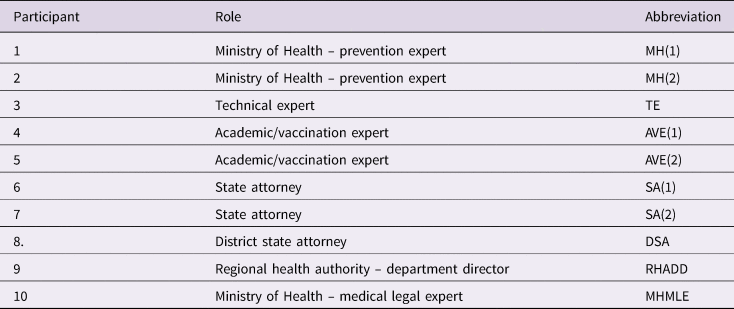

We augmented our documentary analysis with semi-structured face-to-face interviews with professionals inside or privy to the cases or the Italian health bureaucracy. We selected participants through purposive sampling (Flick, Reference Flick2018; McGaughey, Reference McGaughey2018) in light of their direct involvement in (or knowledge of) the Rimini and Milan decisions. Following ethics approvals, we conducted a first round of interviews in November 2018 and a second round in June 2019 (plus one interview in writing completed via e-mail three months later). The details of the recruited individuals are documented in Table 1.

Table 1. Study participants

All interviews were transcribed and imported into the qualitative analysis software NVivo 12. The first and second author collaboratively dual-coded them. The coding process employed inductive and deductive approaches, with the coding tree developed iteratively to inform the structure of this paper. We discussed and refined preliminary results as a full research team twice during the process.

Parts of the analysis focus principally on the Rimini case and the broader institutional context of the decisions, and to a lesser extent on the Milan case. Numerous attempts to schedule interviews with key informants from the District State Attorney's Office of Milan were unsuccessful, and the office eventually refused to participate on the basis that this would contravene their policies. In contrast, the State Attorney's Office in Rome and the district branch in Bologna agreed to participate.

2.4 Systematic newspaper analysis

We conducted a systematic media search, tracking the reporting of the two cases. Press coverage is a valid proxy for societal diffusion of the decisions within Italy and beyond, as newspaper reporting constituted the initial vehicle of dissemination prompting a spike in Internet searches for ‘no-vax’ theories (Aquino et al., Reference Aquino2017). We searched newspaper databases for articles related to first-instance and appellate decisions at a local, national and international level.

Nationally, we selected the five newspapers with the highest number of digital subscriptions.Footnote 4 We used the following keywords to search databases: ‘sentenza/appello’, ‘tribunale’, Rimini/Milano’, ‘vaccino/vaccinazione’ and ‘autism’. We searched the time period between the day of the publication of each judgment and the following fortnight to capture immediate reporting of the decisions.

Locally, we selected the five most popular newspapers for each region involved.Footnote 5 The keywords used for the search and the period analysed were the same as above.

To capture how these cases were reported by the international press, we focused on (1) the UK, where speculations about the link between vaccines and autism first emerged; (2) the US, whose main newspapers have global reach; and (3) France, a neighbouring country with some of the highest vaccine hesitancy in Europe (Larson et al., Reference Larson2016). In each country, we selected the three newspapers with most digital readers.Footnote 6 We used the following search words: ‘court case/appeal’, ‘vaccines/vaccination’, ‘autism’, ‘tribunal’ and ‘Rimini/Milan’. For newspapers in French, we used ‘action en justice/recours’, ‘vaccine/vaccination’, ‘autism’ and ‘Rimini/Milan’. The search period extended from the day of the publication of the judgments to the end of 2019 to account for lags in foreign investigation and reporting.

3 Findings

3.1 Institutional context

Making sense of the decisions in Rimini and Milan requires understanding the process and institutions involved in vaccine-injury cases in Italy. The court decisions under study arose from a no-fault compensation scheme set up in 1992 to grant redress to individuals or families suffering permanent adverse reactions to several medical interventions including vaccination. The scheme exists under Law n. 210 of 1992, which established a quasi-judicial adjudicative mechanism. Injured parties are entitled to claim a relatively small compensation (an ‘indemnity’).Footnote 7 if they can establish a causal link between the vaccination and the injury suffered. This scheme is a form of ‘social solidarity’ to accompany Italy's (then) four mandatory vaccines (Signorelli, Reference Signorelli2019). Informants SA(1) and (2), MHMLE and RHADD, confirmed that the no-fault compensation scheme was established to provide easily accessible compensation to individuals suffering from known side effects of mandatory vaccines (particularly the polio vaccine). The scheme was extended in 1998 and 2000 in Judgments n. 27/1998 and 423/2000 of the Italian Constitutional Court to include recommended vaccinations, since most vaccinations pursue similar public health policy goals.

The procedure under Law n. 210 of 1992 requires the injured party to initiate proceedings before the competent ‘Hospital Medical Commission’ (HMC). HMCs are based in district military hospitals and staffed by military medical personnel, and already existed to assess ‘other types of damage and therefore were involved in judgements for indemnities paid by the Public Administration’. When the scheme was adopted, ‘it was considered from a political point of view that the military guaranteed a higher level of impartiality [than other settings]’ (RHADD).

HMCs assess whether plaintiffs have established a causal link between vaccine and injury. Our informants observed that military medical personnel typically have no specialisation in virology or immunology and are often orthopaedists or forensic pathologists. Yet, HMCs rely on their own medical expertise and on the evidence adduced by plaintiffs. The system is not adversarial, so there is no counterpart. RHADD described an internal study prepared for his regional health authority showing that most medical reports submitted by plaintiffs in support of HMC claims sanctioned that the contested injury occurred because of vaccination. The same study found a high proportion of doctors filing these reports embracing anti-vaccine positions.

Multiple informants underlined that HMCs have tended to engage in what they described as welfarist decision-making. Even in the absence of compelling scientific evidence linking damage to vaccine, HMCs have historically shown willingness to award indemnities as a form of relief to families struggling with significant health problems. SA(2), AVE and TE linked this to the relatively small sums of money involved. RHADD added the following observation: ‘HMCs are basically composed of soldiers, who often do not investigate the vaccination aspect. So, compensation was seen almost as a social benefit for a disabled person.’

When the HMC rejects a claim, the legislation establishes a right of appeal to the Medical Legal Office of the Ministry of Health (MLOMH). Our informant from that office (MHMLE) explained that if the claim fails again at this stage, the plaintiff retains the right to bring an action before a civil court. This is a no-fault claim based on the same special legislation, where a civil court is called upon to determine the existence of a causal link between vaccination and damage. Crucially, the exact test for causation in Italian civil cases remains unsettled:

‘In uncertain causation cases, courts can either defend the need for proving causation with reasonable precision or resort to procedural and evidentiary technicalities (from reversing the burden of proof to adopting the theory of ‘the most probable cause’) that allow them to establish causation … [This] is one of the main battlefields where the liability game is played.’ (Infantino and Zervogianni, Reference Infantino and Zervogianni2017, p. 95)

The civil-court proceeding is a quasi-adversarial civil action against the Italian Public Administration, represented by the State Attorney's Office. Each party can make submissions and rely on expert evidence, which can be produced through an appointed Party's Technical Consultant (PTC)Footnote 8 or via documentary evidence. In proceedings involving complex technical matters, a civil court typically appoints an Office Technical Consultant (OTC),Footnote 9 who prepares a detailed report to assist the judge in making sense of the technical matters arising in the case. The criteria of appointment for OTC are loosely regulated and the relationship is characterised by the Ministry of Justice as ‘fiduciary in nature’ (Ministry of Justice, 2018). OTC selection is predominantly guided by the judge's own appreciation of an individual's qualifications and expertise. Once proceedings start in the civil courts, the normal rights of appeal to the competent Court of Appeal and to the Supreme Court of Cassation apply. The judgments of Rimini 2012 and Milan 2014 were first-instance decisions of civil courts following initial rejection by HMCs and failed appeals before the MLOMH.

3.2 What happened in the Rimini case

In 2008, the family of a child born in 2002 filed a claim for compensation to the competent HMC. They alleged that the MMR vaccination that the child had received in 2004 caused a generalised ‘multisystem developmental disorder’ diagnosed in 2005 (Ventaloro, Reference Ventaloro2010). The HMC rejected the claim. In 2008, a specialist doctor linked the disorder (now diagnosed as autism) to the MMR vaccination (Ventaloro, Reference Ventaloro2010). After an unsuccessful appeal at the MLOMH, in June 2010, the family brought the case to the Tribunal of Rimini. Interestingly, neither the HCM nor the MLOMH rejected the claim on its merits, but rather on the technical point that the MMR vaccination was not mandatory at the time,Footnote 10 despite the Constitutional Court rulings of 1998 and 2000 on the applicability of the scheme to recommended vaccinations. The substantive issue of causality between the MMR vaccine and autism was never investigated at this level (Ventaloro, Reference Ventaloro2010).

The case moved to the civil court and the competent attorney of the District State Attorney's Office (DSAO), based in the regional capital Bologna, was appointed to follow the proceedings. This lawyer developed a defensive strategy based the technical argument that the Ministry of Health lacked ‘passive legitimacy’ (i.e. was the wrong defendant). This argument relied on the constitutional structure of the Italian health-care system, which is regionally organised, implying that the correct defendant was a local health authority. This defence was filed as a written submission (State Attorney's Office, 2010). However, the Italian Supreme Court of Cassation had established in its Judgment n. 23588 of 2009 that in compensation cases under Law n. 210 of 1992, the Ministry of Health is the correct defendant because it is competent to decide on the merits of the administrative appeals under the scheme.

At the hearing of the trial, in November 2010, the Tribunal of Rimini dismissed the technical defence and moved to the merits of the case. The plaintiff's lawyer was present to make submissions on the merits, but the state attorney was not. The only evidence submitted to the court was therefore that of the plaintiff, linking the MMR vaccine to autism (Ardigò, Reference Ardigò2010). The plaintiff did not appoint a PTC, but relied on medical reports drafted by two specialists who had seen the child after 2008 and posited that autism had been more likely than not caused by the vaccine (Barboni, Reference Barboni2012; Ventaloro, Reference Ventaloro2010). In March 2012, the OTC appointed by the Tribunal of Rimini filed a report confirming the plaintiff's evidence and affirming the existence of a causal link between the vaccine and the child's autism. The OTC's report made extensive reference to the works of Andrew Wakefield – reference subsequently reiterated in the judgment (Barboni, Reference Barboni2012). It bears noting that Wakefield's paper linking MMR vaccination to autism had been retracted by The Lancet in February 2010, two years before the OTC report was filed and the judgment issued.

The Rimini decision was widely reported in the Italian media, both locally (Altarimini, 2012a; Altarimini, 2012b; Il Resto del Carlino – Rimini, 2012) and in three major national newspapers (Il Fatto Quotidiano, 2012; La Repubblica, 2012; La Stampa, 2012). ‘Il Fatto Quotidiano’ and the local newspaper ‘Altarimini’ maintained a neutral tone about the decision and mentioned The Lancet’s retraction. The article in ‘Altarimini’ quoted the Chair of the National Medical Board, who restated the absence of any correlation between autism and vaccination. ‘La Stampa’ reported concerns expressed by the Society of Social and Preventive Paediatrics without describing the case in detail. The only newspaper to give an explicitly favourable opinion on the judgment was ‘Il Resto del Carlino’, which included an interview with the family's lawyer and reported the parents’ satisfaction with the outcome. Internationally, ‘The Daily Mail’ (UK) reported the case with quotes from the family's lawyer vindicating the Rimini decision as ‘the first public admission’ of the risk of developing autism as a result of the MMR vaccine (Daily Mail, 2012).

Upon notification of the judgment to the Ministry of Health, the DSAO filed an appeal to the competent Court of Appeal of Bologna. The appellant presented a wealth of substantive evidence, supported by an expert witness (our MHMLE informant), vigorously endorsed by the appellate OTC. In February 2015, the Court of Appeal of Bologna reversed the decision of the Tribunal of Rimini with prejudice.

The Rimini appeal was widely reported in the media. All national newspapers in our sample reported it (La Repubblica, 2015; Il Sole 24 Ore, 2015c; Il Sole 24 Ore, 2015a; Il Sole 24 Ore, 2015b; La Stampa, 2015; Corriere della Sera, 2015; Il Fatto Quotidiano, 2015a). Locally, the same newspapers that had covered the first-instance decision reported the appeal (Altarimini, 2015; Il Resto Del Carlino – Rimini, 2015). Two articles quoted the Minister of Health and the president of the Italian Institute of Public Health (Corriere della Sera, 2015; La Stampa, 2015). Most national newspapers reported statements of scientific associations expressing satisfaction with the outcome (Il Fatto Quotidiano, 2015b; Il Sole 24 Ore, 2015b; Il Sole 24 Ore, 2015c; La Stampa, 2015). ‘La Repubblica’ was an outlier in covering statements of the family's lawyer, but also quoted the doctor founder of VaccinarSi, a pro-vaccine information website (La Repubblica, 2015). Locally, ‘Altarimini’ briefly described the appeal judgment, emphasising the absence of correlations between vaccines and autism (Altarimini, 2015). ‘Il Resto del Carlino’ reported positive and negative statements from a range of stakeholders, including the family's lawyer (Il Resto del Carlino – Rimini, 2015).

Internationally, most newspaper coverage occurred with significant delay and was predominantly interested in the role that the initial decision had played in the growth of Italian vaccine hesitancy and the ‘no-vax’ movement (Daily Mail, 2019; The Guardian, 2018; The New York Times, 2018).

3.3 What happened in the Milan case

In 2013, another family initiated proceedings before the Tribunal of Milan, seeking compensation for their child's autism. The diagnosis was received in 2010 and the alleged cause was identified in the three injections of hexavalent vaccine the child received in 2006 (Tornatore, Reference Tornatore2014). The family filed a claim to the competent HMC in 2011 and, upon rejection, lodged an appeal before the MLOMH. The HMC and MLOMH dismissed the claim on its merits and the case was moved to the civil court.

The Milan case presents a different dynamic to that of Rimini. The appointed District State Attorney filed a defence on the merits arguing that the onset of autism was likely due to genetic predisposition and that the temporal proximity between the vaccination and theinsurgence of autistic symptoms was irrelevant. However, no supporting evidence from a PTC was presented (Tornatore, Reference Tornatore2014). The plaintiff filed reports from an autism specialist and appointed a PTC who confirmed the probability of a causal link. The state's attorney was not present at the hearing at which the plaintiff PTC's submissions were filed and an OTC appointed. The OTC's report accepted the PTC's conclusion that the vaccine was the most probable cause of the autism by virtue of the ‘principle of exclusion of alternative causes’ (Tornatore, Reference Tornatore2014). No scientific publications, not even retracted ones, have ever suggested the existence of a link between hexavalent vaccines and autism.

The Milan decision received extensive coverage in Italy, with nine mentions in national papers and two in local ones, likely because the Rimini case sowed doubt within the population and interest in the media. By 2014, vaccination had become a national issue as rates were beginning to fall (Aquino et al., Reference Aquino2017; Attwell et al., Reference Attwell2018). ‘La Repubblica’ covered the case extensively (Bocci, Reference Bocci2014; La Repubblica, 2014a; La Repubblica, 2014b; La Repubblica, 2014c; La Repubblica, 2014d; La Repubblica – Milano, 2014). One article framed the judgment positively and cited the family's lawyer stating that the decision was final, as the ministry did not appear to have appealed. This article also mentioned an Australian report about the presence of mercury in vaccines, countered by the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA)'s declarations about the safety of the vaccine (La Repubblica, 2014d). ‘Il Fatto Quotidiano’ took a relatively favourable stance on the judgment but reported the decision of the ministry to appeal (Il Fatto Quotidiano, Reference Il2014a; Il Fatto Quotidiano, 2014b). This coverage described the Milan case as occurring within a period of international debate about vaccines and autism, and included the Rimini judgment and public health authorities’ reactions, as well as an official investigation in the city of Trani on the vaccines–autism correlation (Rizzo and Rota, Reference Rizzo and Rota2016). Only one voice favourable to vaccines was included – the president of the Italian Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association (‘Farmaindustria’) stating that vaccines are less expensive than treating diseases.

Subsequent articles in ‘La Repubblica’ came out more strongly against the judgment, including critical expert commentary and reactions from politicians, doctors and pharmaceutical companies, as well as reporting that the ministry had appealed the decision (La Repubblica, 2014b; La Repubblica, 2014c). The second article also reported a declaration by ‘Condav’, the national association of victims of vaccine injury, demanding investigations into the potential harms related to vaccinations as well as prevaccination tests to identify vulnerable subjects. Reports in ‘Il Corriere della Sera’ were critical of the decision, including calls from professional associations for parents to keep trusting vaccination, for the National Medical Board to discipline OTCs who do not follow scientific evidence and for greater ministry participation in lower-court decisions (Corriere della Sera, 2014a; Corriere della Sera, 2014b).

Locally, two newspapers reported the decision. ‘Il Giornale’ interviewed an infectious diseases expert about the ‘Fluad case’, in which deaths of elderly Italians were incorrectly linked to influenza vaccination (Signorelli et al., Reference Signorelli2015). It also referenced the Milan case, denying any correlation between vaccines and autism (Il Giornale, 2014). ‘Milano – Le Repubblica’ provided sympathetic coverage of the parents’ experience with their child's disorder and did not provide any opinions of vaccination experts (La Repubblica – Milano, 2014).

The Milan decision was not reported in the international newspapers analysed.

On appeal, the state's attorney focused their argument on the lack of scientific foundations for the thesis linking vaccines to autism, supported by a PTC from the MLOMH (again, our MHMLE informant). The Court of Appeal of Milan overturned the first-instance decision, with the appellate OTC vigorously endorsing the ministry's expert.

Surprisingly, the Milan appeal received no newspaper coverage. Several of our informants were not even aware of it, corroborating that there has been no dissemination.

3.4 Mapping the network: three layers of analysis

3.4.1 Following the actors in the Rimini (and Milan) decisions

An important aspect of the Rimini decision was the trial strategy adopted by the defence, which was exclusively based on the technical point of law that the Ministry of Health was the incorrect defendant. The Supreme Court of Cassation had ruled in 2009 that the ministry is the correct defendant in other areas of compensation covered by the Law n. 210 of 1992 (blood transfusions). The same court confirmed this finding in Judgment n. 29311 of 2011 for vaccine-injury cases brought before civil courts under that scheme. Arguably, a DSA dealing regularly with matters falling under this legislation should have been aware of this jurisprudential trend in 2010, when the case was filed. The Bologna DSA informant, who tried the case on appeal, suggested two reasons for the choice of this defence. First, it had been successful in other types of cases brought under the same scheme (legal disabilities). A simple error of judgment could therefore explain the choice of strategy: ‘In my opinion, it was an oversight. Usually, we win these disputes based on defences in law. If [the lawyer] had realised the real content of this claim, they would probably have paid closer attention’ (DSA).

Reliance on this technical defence also stemmed from a lack of resources and overwhelming workload imposed on the State Attorney's Office and its district offices. Limited resources underpin why the state attorney did not participate in the Rimini hearing. Indeed, DSAOs rarely send lawyers to hearings in provincial tribunals, normally appointing a delegate of the administration or a private lawyer. However, in this case, there was no representative of the defendant: ‘this judgement went ahead without any kind of contribution on the merits from the state attorneys and from the administration’ (DSA).

A further issue in both the Rimini and Milan decisions relates to the interactions between State Attorney's Offices and the Ministry of Health, which possesses the relevant technical expertise. Court transcripts and our informants’ accounts show a substantial lack of communication at first instance (Tornatore, Reference Tornatore2014; Ventaloro, Reference Ventaloro2010). MHMLE provided a detailed account of the exchange of information between their office and the DSAOs of Bologna and Milan. In both cases, all relevant communications took place for the purpose of the appeal, with no recorded exchange at first instance.

A final crucial factor in the Rimini and Milan decisions was the role of the court-appointed OTC – the expert tasked with navigating the judge through the complexities of technical and scientific evidence. DSA underlined how in the Rimini decision, the OTC's appraisal of the plaintiff's scientific evidence was passive and uncritical:

‘Where one side has not provided scientific evidence, it is not automatic that the OTC must accept the evidence provided by the other party uncritically as it happened here. The judge … also uncritically accepted this report. They were very superficial in their acceptance …. It would have been enough to search Wakefield on the internet to see that it was not a reliable source.’

MHMLE underlined the same point about both the Rimini and Milan decisions and added:

‘It is extremely important to have an open and receptive OTC in front of you, ready to “listen” and not just “hear”. Enlightened professionals, such as those involved in the appeals of the Rimini and Milan decisions, could only come to the same conclusions of the Ministry's PTC. This is because they applied the methodology and drank from the springs of science that could only lead them to the same conclusion: the denial of the causal link between vaccination and autism.’

A specific factor in Rimini was that the OTC appointed by the court notoriously harboured anti-vaccine sentiments: ‘Clearly, he is a subject who is certainly not in favour of vaccinations’ (RHADD).

3.4.2 ‘Weaving through things’: relations within the legal process

Following the actors in Rimini and Milan requires looking beyond the specifics of the two cases to appreciate the context in which these actors ‘weave through things’.

Our qualitative data highlighted poor communication practices between the ministry and State Attorney's Offices. In both cases, communications were initiated only at the appellate level and appear systemically clunky: ‘The extreme formalization and bureaucratization of communications prevented awareness of the need to appear in court in punctually, with precise arguments’ (RHADD).

This comment, corroborated by a number of informants (DSA, MHMLE, AVE(1) and (2), TE), resonates with a general dissatisfaction expressed by SA(1) and (2) that it is often hard to obtain technical information on pending cases – and even harder to get it on time. This leads to a second issue identified as the lack of ministry resources to support legal cases: ‘The Ministry was often not adequately resourced to be able to provide a timely and fully formed opinion for the State Attorney to appear in court, with well documented arguments that had been properly thought through’ (RHADD).

SA(2), tasked with representing the ministry in the last instance of the Rimini case before the Supreme Court of Cassation, was running out of time to file his submissions waiting for input from the ministry, and thus took the matter into his own hands:

‘I felt the duty, because I realized that it was an extremely sensitive matter, to look on the internet for news that referred to this Dr Wakefield, because the judgment cited him extensively. So, simply by searching the internet, I was able to prepare a useful defence, because the judgment was based on a study that had been debunked by medical literature. It was easy to prepare a defence, which was confirmed by the report of the Ministry.’

The general sentiment at the State Attorney's Office was that overwhelming numbers of cases lay at the root of the suboptimal (and untimely) exchange of information between the ministry and their office: ‘Objectively, we have difficulty interacting in a timely and thorough manner. There are cases treated with extreme punctuality and timeliness. Others, due to the enormous mass of disputes, are perhaps missed’ (SA(1)).

It is in this context that we must appreciate the decision to file a defence on a single point of law in Rimini, or a substantive defence not corroborated by PTC testimony in Milan. DSA suggested that the Rimini strategy could have been an oversight by the assigned lawyer due to the number of disputes based on the same legislative scheme but for other types of injuries that her office dealt with. In her words: ‘taken from a billion files’, this one did not receive adequate attention.

Insufficient resourcing and overburdening also contribute to a tendency, observed by AVE(1) and (2) and TE, to get involved only at the appellate level. The reasoning being that normally judges reach a satisfactory decision at first instance and, if not, the damage can be repaired with a proper trial strategy on appeal. The combined effect of poor co-operation practices between the ministry and the State Attorney's Office, and the lack of adequate capacity appear to have resulted in ‘silos’ preventing effective action (Graycar and Mccann, Reference Graycar and Mccann2012).

A parallel factor emerging from our data is an attitude towards welfarism in judicial decision-making related to claims under Law n. 210 of 1992, mirroring the HMCs’ attitude discussed above. Several informants pointed to this aspect (MH(1) and (2), AVE(1) and (2), and TE). SA(2) summarised the matter:

‘In the last 10–15 years, courts have developed a line of case law that I call “welfarist”, because they take a socially relevant problem [vaccine injury or other injury covered by the scheme] and allocate its burden onto an entity believed to be able to bear the consequences [the state].’

Such welfarist decision-making speaks to beneficent intentions on the part of judges seeking to improve the lives of suffering families. However, dispensing relatively small amounts of ‘welfare’ amplified the content of the claims. Decision-making based on kindness rather than robust scientific evidence had significant and unintended consequences for Italian parents’ vaccine confidence (Attwell et al., Reference Attwell2018; Aquino et al., Reference Aquino2017).

Finally, a common characteristic of the medical doctors appointed as OTCs in the Rimini and Milan cases is that both were forensic pathologists, with no specialist vaccination knowledge (Barboni, Reference Barboni2012; Tornatore, Reference Tornatore2014). This is attributable to the peculiar regulation of OTC selection in Italian civil procedure. Title II of the ‘Implementing Provisions’ of the Italian Code of Civil Procedure clarifies that each tribunal must have a registry of OTCs. Registration follows an application to a special committee composed of judicial officers, members of the tribunal's administration and a representative of the relevant profession. Registered OTCs are organised reflecting broad areas of expertise. For medical expertise, Article 13 simply requires the registry to include ‘medical and surgical expertise’ not otherwise specified. Article 22 establishes that, normally, the competent judge selects an OTC for a specific case using the tribunal's registry. However, a judge can appoint a non-registered OTC provided they justify their choice. This broad categorisation of expertise and high degree of discretion set the scene for forensic pathologists providing technical opinions on matters outside their expertise, creating fertile conditions for a ‘zombie’ idea to rise from the grave.

The institutional context of OTCs exposes further avenues for ‘zombie ideas’ to attain credibility. RHADD expressed concerns about the light-touch gatekeeping for scientific rigour and the standard of eligible OTCs. There are no real consequences for OTCs who file reports lacking scientific credibility. This is at odds with the ethical duties of OTCs as medical doctors and elevates the risk of zombie ideas reanimating as valid and decisive legal evidence. The report filed by the OTC typically concludes with some version of the statement: ‘The content stated above is my personal conviction’ (e.g. Tornatore, Reference Tornatore2014). The report is thus based on the convictions and personal experience of the OTC (with no guarantee that their expertise is directly relevant to the matter at hand) rather than a rigorous scientific method:

‘If these reports – which say absolute lunacies from a scientific point of view (and we have read many) – went to the National Medical Board, their authors could be sanctioned from a disciplinary point of view, because they have disregarded the scientific nature of the data. Judges should perhaps do something more, such as remove them from the registry of OTCs, because they have essentially produced unethical reports.’ (RHADD)

3.4.3 Broader influences on actors’ relations

In addition to factors directly linked to the legal process, the general environment in which the Rimini and Milan actors operated also played an important role in the development of these cases as ‘socio-legal objects’. Our data point to two complementary deficiencies leading up to the judgments.

The first was a generalised lack of awareness of the sensitivity of vaccination. The Rimini case, filed in 2010, triggered insufficient alarm at the Ministry of Health according to SA(1). The notion that a causal link may be established between vaccine and autism was regarded as unbelievable, so the case ‘was not a priority’ (AVE(1)). The competent administrations at the time ‘did not realize how important that story was’ (AVE(2)). Reflecting on the years between the Rimini and Milan decisions, RHADD described a pervasive underestimation of the anti-vaccine sentiment, still regarded as a niche social phenomenon with limited reach. He added:

‘The media coverage of the importance of immunization rates for public health has [since] affected higher spheres in the country, including in the judiciary, raising awareness of the issue. A few years ago, during these judicial proceedings, awareness was not there at every level.’

Lack of awareness can shed light on certain aspects of the dynamics of the cases, such as the ministry's lack of input at first instance. However, some informants provided alternative views. DSA argued that her office was aware of the sensitivity of the issue, and she perceived the ineffective strategy at first instance as a possible oversight. MHMLE similarly posited that the ministry was in no danger of underestimating threats to vaccine confidence. Yet it did not intervene at first instance in either case.

A further factor influencing initial institutional responses was an underestimation of the potential risks of unfavourable decisions at first instance (Maor, Reference Maor2014). Most of our informants converged on this point: the perception was that an unfavourable judgment would have been unlikely, and in any event would have done no lasting damage as an adequate use of resources on appeal would guarantee an overruling. Whilst correct from a strictly legal perspective, such thinking is strategically short-sighted. Even first-instance decisions can have a devastating extra-judicial impact when they propagate a ‘zombie idea’ (Aquino et al., Reference Aquino2017; Carrieri et al., Reference Carrieri, Madio and Principe2019).

3.5 Aftermaths and learnings

The dissemination of the Rimini and Milan decisions prompted us to keep following the actors after the judgments. We found three sets of impacts: (1) corroboration of the impact of these cases on vaccine hesitancy in Italy; (2) specific consequences for families engaging with the compensation scheme and for its administration; and (3) lessons that public health authorities and state attorneys derived from the experience.

3.5.1 Societal consequences – corroboration of existing knowledge

Except for MHMLE, our informants consistently maintained that the decisions in Rimini and Milan had significant societal impact, which unfolded in three separate but related ways, corroborated by our media research.

The first consequence is the wide dissemination of the decision via newspapers, subsequently picked up by social media. This caused great concern for state attorneys:

‘The Rimini ruling is still on social media. It has been amplified in a crazy way. Once I thought about responding to a social media group … to alert people that the Bologna appeal had come out. I wanted to make people aware of this, so I brought their attention to the appeal decision.’ (DSA)

SA(1) and (2) explained that it is impossible to confine the effects of a judgment to the legal system, and that the broader impact that any decision may have should be better addressed:

‘Clearly today through the Internet, a single ruling can have a very strong effect on public opinion. Even devastating, I am sorry to say. This certainly changed the game. Today, unfortunately, it is no longer possible to deal with certain events in court without being mindful of the echo in the media that these judgments may have.’ (SA(1))

For SAs(1) and (2) and DSA, dissemination should be considered in the legal process, but State Attorney's Offices are not equipped for this. They corroborated, as did the newspaper coverage, the rise of the vaccine–autism ‘zombie’ and its impact on vaccine hesitancy, expressing concerns that Rimini and Milan legitimised otherwise marginal views:

‘Before, “no-vax” was not worth much in the public image and in the collective culture. Certainly, with these decisions … the impetus grew incredibly. Then other beliefs developed: that there is a strange and perverse game of the pharmaceutical companies, that the Ministry makes money out of it. Then the web makes everything bigger, and people already partly convinced … begin to stop vaccinating. This is an objective fact. There has been a decline [in vaccination rates], and these judgments have contributed in some way. Because everyone knows the Rimini decision, but very few know the Bologna appeal.’ (DSA)

MHMLE agreed that the finding of a causal link between vaccine and autism facilitated the ‘advertising and dissemination of incomplete and untruthful data’. RHADD described a ‘perfect storm’: ‘A series of events were concentrated in the years 2012–2014 that played for the “no-vax” opinion groups. Among these events were these two judgments, so the “no-vax” had a series of robust arguments from their point of view.’

The ultimate consequence of decreased vaccination rates was the implementation of the 2017 mandatory vaccination law. It bears restating that the argument here is not that there was a neat causal relationship between the Rimini and Milan decisions and Italy's adoption of a new mandatory vaccination regime. But it is increasingly clear that these particular ‘socio-legal objects’ were part of that process.

3.5.2 Consequences for families and administration of the scheme

The Rimini and Milan decisions were overturned with prejudice on appeal, so neither had any lasting legal impact. There is now a consolidated line of case-law from the Supreme Court of Cassation resolutely denying the existence of a causal link between vaccines and autism (Breda, Reference Breda2018; Parziale, Reference Parziale2017). However, there is more to the story than this purely doctrinal observation.

There have been consequences for families of autistic children. DSA regarded the creation of false expectations for families as the Rimini decision's worst impact. She observed a surge in appeals against HMC decisions:

‘The families of autistic children are often connected because they share an important problem. In Rimini, we saw many more appeals starting to be filed …. In a small town, when a favourable ruling came out on such an important issue, and since someone must be blamed, the propensity of people to bring claims clearly increased.’ (DSA)

Beyond Rimini, MHMLE observed a national trend that saw a surge in appeals brought to the MLOMH after 2012 for cases of autism allegedly resulting from vaccinations. The Rimini and Milan decisions contributed to boosting unwarranted and unsatisfied expectations of both vindication and economic relief in families facing difficult diagnoses.

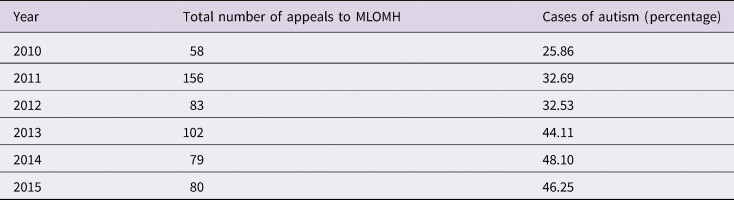

Data collected between 2010 and 2015 concerning autistic diseases show a progressive increase in indemnification claims, going from 25.86 per cent in 2010 to 46.25 per cent in 2015, with the breakdown shown in Table 2 (provided by the MHMLE informant).

Table 2. Trend in indemnification claims 2010–2015

3.5.3 Lessons and learnings

The aftermath of the decisions prompted our informants to undertake several critical self-reflections, further enriching our tapestry of interactions. We identify both positive changes to practice and lessons learnt but not implemented.

Changes in practice are diverse but share a common theme: greater attention is now given from the beginning to cases involving potentially sensitive public health issues. This may be the most significant lesson acted upon after the Rimini and Milan decisions, as stated by SAs, MHs, AVEs and TE. MHMLE was less inclined to acknowledge a change and argued instead that vaccine cases had already been a priority for the ministry since 2010. Yet, we know that in both cases, the ministry only got involved on appeal.

The Rimini and Milan decisions also contributed to a broader change in the decision-making practices of HMCs. RHADD observed that their modus operandi now adheres more to the letter and purpose of the legislation:

‘Before, military doctors made their decisions independently. In these investigations … there is no requirement for technical experts providing vaccination services to brief [the decision-maker]. Now, it seems that in cases where the assessments are complex, they [HMCs] ask the Ministry for advice, which they did not do before.’

RHADD also explained that some regions have developed mechanisms of continuous consultation between regional health authorities, DSAOs and Offices of Public Prosecution for vaccine matters. These provide courts, prosecutors and state attorneys with lists of OTCs who are experts in vaccination. Such individuals can be reliably consulted as a PTC for the Ministry or as an OTC for the courts in matters involving vaccines.

DSA referred to a change in judicial attitude involving both more rigorous selection of OTCs and independent research on the quality of OTC reports. She mentioned the case of Judge Ardigò, who issued the Rimini decision but has since vigorously rejected the existence of a causal link between vaccines and autism in a subsequent judgment of 2017. DSA considered this to be of great significance because this judge ‘normally quotes himself and is very self-referential’. This was a positive change in judicial attitude, she said, ‘even in the stronghold that created this problem for us’.

There are, however, two very significant lingering issues. The first concerns the ability of governmental actors, whether from the ministry or the State Attorney's Office, to adequately communicate and disseminate positive results of cases. SA(1) argued that in the era of mass and social media:

‘We cannot consider certain procedural initiatives only for what is their present value. Instead, we must also consider them for the media effects that they may have tomorrow. And therefore this, in my opinion, should be one of the criteria of evaluation in organizing a proper reaction in court by the Ministry, and then by the State Attorney's Office.’

This recommendation remains to be acted upon. DSA lamented a general lack of initiative in disseminating the positive achievements of their office. A clear example is the lesser dissemination of the Bologna appeal compared to the Rimini decision and the absence of reporting on the Milan appeal:

‘[T]he idea of a press office, or an office that “represents us” and monitors cases … is one that has not yet prevailed. But in my opinion, it would not be wrong at all. Because it is all left to the individual lawyer, to both practice the law and then also to intervene to correct biased views. This should not be done by individuals. The institution should do so, on such important issues.’

The second major problem is equally systemic and difficult to address: the design of the OTC system for civil cases. While each court district compiles registries of OTCs, these are only broadly framed and judges remain free to appoint whomever they see fit. In this sense, the initiative described by RHADD, in which regional authorities compile lists of registered OTCs with specific medical expertise, remains of limited scope. The OTC system was salient for all our informants. The most powerful statement came from RHADD:

‘OTCs are doctors first, and subsequently also OTCs. They are consultants to judges, who are not omniscient and must rely on the assessment of expert advisors. So, the reasoning I put forward is this: when OTCs support their conclusions with a study from a scientific journal that has been withdrawn, they commit two “wrongs”. First, from an ethical point of view, they are failing to uphold their oath, because they refer to a scientific fact that is not true, which should be sanctionable. Secondly, they are making unfaithful reports based on false data. This should be punishable by the judiciary because they have given unfaithful advice to the court – not telling the truth – and by the National Medical Board, because they are doctors who are not making scientifically sound decisions.’

Notwithstanding these serious concerns, the OTC system remains unchanged. The Ministry of Justice maintains that registration is predicated on high moral and professional qualities, but the decision on whom to appoint in any given case rests with the judge. Because the appointment is fiduciary in nature, registries effectively contain mere suggestions (Ministry of Justice, 2018). This keeps the door open to future risks in litigation involving contested areas, with more zombies lurking – even if there is now consolidated case-law on the specific issue of vaccines and autism.

4 Of truths, symmetries and the parallel lives of ‘zombies'

The principal objective of this paper was to tell a fascinating story. We consciously chose to make room for the findings to speak for themselves, with relatively limited commentary. The story remains the protagonist; however, the entangled network emerging from our data elicits analytical observations. Two are of particular interest. The first concerns what our findings say about the broader issue of truth production in court settings; the second concerns how given propositions can live symmetrical lives in different contexts – in this case: the scientific and the socio-legal.

4.1 Creating truth in court: teleological tensions

Scholars across jurisdictions have analysed the so-called ‘gatekeeping’ function of courts. This refers to the process of regulating the admission of scientific evidence and expert witnesses in court cases. In the US, the Daubert trilogy of cases established a lasting test in complex litigation (Allen and Leiter, Reference Allen and Leiter2001; Caudill, Reference Caudill2001; Caudill and LaRue, Reference Caudill and LaRue2003; Cranor, Reference Cranor2016). This has been under scrutiny for some time because of the risks of abuses intrinsic to a purely adversarial process. Whilst imperfect in design, the Daubert model is teleologically geared towards restricting court access to evidentiary material and expertise that passes a preliminary ‘assessment of whether the reasoning or methodology underlying the testimony is scientifically valid and of whether that reasoning or methodology properly can be applied to the facts in issue’ (Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharnaceuticals 509 U.S. 579 (1993), 592).

In European legal systems, in which the relationship with technical expertise is less adversarial and filtered through the lens of court-appointed experts, difficulties arise from the inherently ‘black box’ production of legal evidence. This was recently analysed in the context of the French legal system, in which ‘the factual nature of expertise reports is guaranteed without experts having to justify what they say on every occasion’ (Juston Morival and Pélisse, Reference Morival R and Pélisse2020, p. 355). The issue of ‘evidentiary gatekeeping’ remains similarly lacking in the broader European continental legal context (Rizzi and Vicente, Reference Rizzi, Vicente and de Almeida2019). This is particularly true in Italy, where the relationship between the expert and the judge is predominantly framed in fiduciary terms. The system is more designed to enable the collaborative co-production (Jasanoff, Reference Jasanoff2004) of judicial truth, rather than squarely focusing on the epistemic or methodological validity of the evidence in scientifically complex cases.Footnote 11

This study vividly illustrates how the OTC system can foster a paradox: judges retaining discretionary powers to identify and appoint OTCs, whose very purpose is to guide judges through evidence that they are not able to evaluate autonomously. This institutional design can be prone to unexpected ‘bifurcations’, especially in civil litigation in which the test for causation is open-ended, accountability for OTC reports is limited and decision-makers show ‘welfarist’ inclinations. From a purely epistemic perspective, reports by OTCs touching on issues beyond the scope of their area of specialisation can be characterised as ‘epistemic trespassing’. These are acts of ‘thinkers who have competence or expertise to make good judgments in one field, but move to another field where they lack competence – and pass judgment nevertheless’ (Ballantyne, Reference Ballantyne2019, p. 367; DiPaolo, Reference DiPaolo2021).

It is tempting to reduce the Rimini and Milan decisions to circumstantial instances of decisions based on this kind of trespassing by medical experts lacking the relevant specialist knowledge. However, this study shows that the risk is systemic and calls for a careful balance between the gatekeeping and co-productionist functions of expert evidentiary rules in court. This is a key institutional response to scientific complexity and uncertainty (Braun and Kropp, Reference Braun and Kropp2010; Jasanoff, Reference Jasanoff1995; Landström et al., Reference Landström2015), particularly in light of the non-neutrality of expertise (Jasanoff, Reference Jasanoff and Jasanoff2012).

4.2 The multiple lives of a dead theory, and the rise of a dead case

‘Law, marching with medicine but in the rear and limping a little, has today come a long way.’

This famous quote from Justice Windeyer in the Australian case of Mount Isa Mines Ltd. v. Pusey ((1970) 125 CLR 383) effectively captures the structural time lag between scientific and legal developments. The Milan and Rimini decisions are part of this lasting history of constant catching up, which has prompted equally lasting debates, within both scholarship and judiciaries, on what to do about it (Haw, Reference Haw2014). However, the dynamics of the decisions and the multiplicity of actors and factors involved prompt further reflection.

Our case-studies arguably provide renewed validation to the ANT idea of ‘general symmetry’, whereby scientific and social truths (or indeed ‘untruths’) follow similar patterns of development and legitimation (Nimmo, Reference Nimmo and Nimmo2016). Taking a step back from our declared position of acceptance of the scientific-community consensus (that there is no link between vaccines and autism), we observe the following. Our story shows an idea (the vaccine–autism proposition), which is raised in a particular sphere (the scientific community in the late 1990s), subsequently killed within that sphere (The Lancet's retraction of 2010), only to be revived in a different sphere (the legal one, in Rimini in 2012) and socially disseminated through both traditional and social media (post 2012). This continued even after its technical death in the legal sphere (through the Bologna and Milan appeals in 2014–2015), as the Rimini decision remained widely searched and read, and the Milan appeal ignored.

The story of these decisions suggests that encounters between actors broadly operating within legal spheres and scientific ideas (regardless of their validity within the scientific sphere) can produce very resilient ‘material worlds’ (Pottage, Reference Pottage2011, pp. 621–643; Reference Pottage2012) with lasting contributions to the shaping of societal convictions and governance. It also reinforces approaches that recognise the ability of propositions to live ‘multiple lives’ (e.g. in scientific papers, retractions, judicial decisions, media reporting and subsequent social interactions), while coherently maintaining a fundamental essence (in this case the vaccine–autism link) (Mol, Reference Mol2003).

The resilient materiality of encounters between law and science, and the potential for ideas to live a multiplicity of lives, prompts us to see the Bologna and Milan decisions as cautionary tales. Indeed, if one is to take the normative position of accepting, as we do in this case, the validity of scientific findings within the scientific community, such materiality and multiplicity can become the birthplace of insidious ‘zombies’. This is not to say that dominant positions in the scientific community should be uncritically greeted with deference in the socio-legal sphere. Rather, legal systems should be equipped to consciously confront this reality instead of being passively subjected to it, as our study exemplifies.

5 Conclusion

This paper presented a detailed account of the Rimini and Milan decisions, their impact and their aftermaths. We used an actor–network approach, mediated by a pragmatist analytical distinction between actors internal and external to the legal system. Several discrete but often interconnected issues emerged. These include the ways in which institutional design impacts judicial use of expertise; processual factors relevant to judicial decision-making; and the intimate interconnectedness of the legal system with a panoply of broader circumstances. Collectively, these actors combine ‘into a very local, very practical, very tiny locus’ (Latour, Reference Latour1999, p. 17) – here, the legitimation of a ‘zombie idea’.

Complementary to the central themes of judicial truth production and the symmetrical progressions of a disproved theory and overruled decision was the centrality of processual factors, in particular trial strategies. This observation suggests a point of connection between the unfolding of legal proceedings and external factors such as resourcing. While trial strategies in Rimini and Milan cannot be solely imputed to scarcity of means, this has constituted a major thread in our tapestry and showed how exposed legal processes can be to this variable.

Further external variables impacting the flow of the legal process include the levels of communication and co-operation between public bodies performing distinct but necessary roles to ensure that courts perform their ‘craft’ competently with respect to cases involving complex scientific matters (Dumoulin, Reference Dumoulin2000; Reichman, Reference Reichman2007). The insufficiency of co-operative practices in Rimini and Milan (only partially imputable to resourcing) serves as an admonishment against a tendency to think in ‘silos’ (Graycar and Mccann, Reference Graycar and Mccann2012) – which is equally damaging whether performed by actors internal or external to the legal system, or both.

Disproved scientific theses such as Wakefield's autism claim can become dangerous ‘zombies’ undermining key public health goals. This was the case for the Italian population's confidence in childhood vaccination from 2012 to 2017. This study advances our understanding of how such ‘zombie ideas’ can receive unwarranted patents of legitimacy. It vividly illustrates that legitimation can stem from intricate interactions, as opposed to neat relationships of cause and effect. With vaccination set to remain a prominent public policy topic, it is essential for legal systems to interrogate and address their internal functioning and interactions with external factors in this delicate space.

Conflicts of interest

None

Acknowledgements

We first and foremost owe a debt of gratitude to our participants for their generosity. We also wish to thank Christophe Lazaro, Tamara Tulich and Fiona McGaughey for comments on earlier drafts, as well as the two anonymous reviewers for their thorough and thoughtful feedback. All mistakes remain our own.