One of the more interesting paradoxes in American life is the high level of contentious political speech presented in the media and the relatively low level of cross-cutting political talk among citizens (i.e., talk among those with different views). There is little evidence of the intensity of political debate as shown in the media in the everyday lives of US citizens. Although the angry rhetoric and hyperbole may not be worthy of emulating, there are few public spaces for citizens of different viewpoints to come together to discuss difficult public issues. In The Big Sort (2008), journalist Bill Bishop documents the increasing ideological segregation of US communities: liberals move to areas with like-minded neighbors; conservatives locate to geographic areas where they will find support for their beliefs next door. The result is that in their everyday lives, citizens are less likely to encounter people who challenge their beliefs.

Research suggests that the majority of US adults engage in some form of discussion about political issues (Jacobs, Cook, and Delli Carpini Reference Jacobs, Lomax Cook and Delli Carpini2009). However, not only do people generally associate with those who are like-minded (Mutz Reference Mutz2006), they also take action to avoid exposure to views that challenge their own (Green, Visser, and Tetlock Reference Green, Visser and Tetlock2000). In a study of American and British adults, Conover, Searing, and Crewe (Reference Conover, Searing and Crewe2002) found that people avoid cross-cutting political talk because they fear that they lack sufficient knowledge or they do not want to offend anyone.

Democratic political theorists have long advocated the public exchange of divergent perspectives as a way of uncovering weak ideas, promoting community, and developing democratic citizens (Habermas Reference Habermas1989; Mill 1859/1956). However, the public spaces for these discussions appear to be decreasing.

Among youth, Parker contends that public school is “the best available site for democratic political education” (2010, 2822) because it is a public place characterized by diversity (more or less), and problems are inherent in the need to live together in that space. Notwithstanding the documented resegregation of schools (Orfield and Lee Reference Orfield and Lee2007), public schools afford young people the best opportunity to encounter, sit beside, and work with those who hold views different from themselves.

Yet, research consistently finds that robust discussions of controversial public issues are not commonplace in classrooms (Conover and Searing Reference Conover, Searing, McDonnell, Michael Timpane and Benjamin2000; Gimpel, Lay, and Schuknecht Reference Gimpel, Celeste Lay and Schuknecht2003; Kahne, Crowe, and Lee Reference Kahne, Crowe and Lee2012). The lack of such discussions often is attributed to teachers’ concerns about their lack of content knowledge, their ability to “control” a spirited discussion, and potential parent complaints. The press for content coverage—currently exacerbated by state-mandated testing—also dissuades some teachers from engaging students in extended discussions. Thus, although diverse viewpoints may exist within classrooms, there may be little opportunity for students to be exposed to those views (Hess Reference Hess2009).

Structured Academic Controversy (SAC) is one pedagogical model for deliberating controversial public issues (Johnson and Johnson 2009). The purpose of our study was to examine whether participation in SAC resulted in positive civic outcomes for secondary students—including greater self-perceived issue knowledge and enhanced perspective-taking skills—as well as whether students’ deliberations led to less variance in opinion.

Whereas debate encourages both sides to present their best argument without acknowledging any weaknesses in their argument, the deliberative process focuses on finding the best possible solution among alternatives.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK AND RELATED RESEARCH

Theory and research related to (1) deliberative democracy, and (2) Structured Academic Controversy (SAC) are relevant to our study.

Deliberative Democracy

Deliberative democracy, as envisioned by theorists (see Gutmann and Thompson Reference Gutmann and Thompson1996; Habermas Reference Habermas and Benhabib1996), occurs when ordinary people of diverse backgrounds come together to discuss common issues of importance. Through this process, people with conflicting viewpoints work through areas of disagreement. After they have intentionally considered all viewpoints, solutions, and consequences, group opinion may begin to converge on a way to address the issue(s) at hand. Everyone may not agree, but the public conversation should reveal areas of agreement around which a solution can be built.

Deliberation is not debate. In debate, there typically are two opposing viewpoints and the goal is for one side to win, to prove that their solution, idea, or opinion is superior to that of the other side. The goal of deliberation is to provide a space wherein all viewpoints are heard and interrogated. Whereas debate encourages both sides to present their best argument without acknowledging any weaknesses in their argument, the deliberative process focuses on finding the best possible solution among alternatives.

Deliberation usually is studied in settings that have been designed intentionally to foster this type of dialogue, such as Brazil’s public-management councils (Coelho, Pozzoni, and Montoya Reference Coelho, Pozzoni, Montoya, Gastil and Levine2005); Fishkin’s deliberation polls (available at http://cdd.stanford.edu); the Jefferson Center’s citizens’ juries (available at www.jefferson-center.org); and the National Issues Forums (available at http://www.nifi.org). Two studies have shown that participation in activities such as deliberative polls (Fishkin n.d.) and deliberative forums (Barabas Reference Barabas2004) increases participants’ issue knowledge and results in significant opinion change.

Structured Academic Controversy (SAC)

The benefits of discussion for deepening student knowledge and promoting greater perspective taking is well established (for an overview of the research, see Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools 2011). SAC involves deliberative discussion and it shares characteristics with other group learning strategies (e.g., Centellas and Love Reference Centellas and Love2012) in that it is collaborative, active, and goal-oriented learning. However, SAC is distinctive because it involves a series of steps that encourage students to examine two sides of an issue.

After an issue has been chosen, the teacher divides students into groups of four. Within these groups, two students are assigned to each position. Pairs read source materials, prepare their reasons for supporting their position, and then the “pro” pair presents while the “con” pair listens and takes notes. It is important that students then switch sides and those originally assigned to the “con” position are tasked with presenting the “pro” side and vice versa. After studying both positions, students abandon their roles and find areas of consensus based on the merits of the arguments.

The theory of constructive controversy suggests that exposure to views dissimilar to one’s own leads participants to experience conceptual conflict, which prompts epistemic curiosity. The result “is an active search for (a) more information and new experiences, and (b) a more adequate cognitive perspective and reasoning process in the hope of resolving uncertainty” (Johnson and Johnson 2009, 41). Disequilibrium in a debate situation may prompt participants to grow more steadfast in their original positions. Because SAC values the best possible solution instead of winning the argument, Johnson and Johnson (2009) contend that participants become more open to possibilities and use new information to devise novel ways to address the issue. The SAC process is grounded in positive goal interdependence, which encourages collaboration among students. The deliberative process allows for the two opposing positions to become sources of information in the pursuit of the best possible solution. In a meta-analysis of 39 studies of SAC with primary-grade children through adults, Johnson and Johnson (2009) found that participation in a SAC produced more positive results than individualistic learning and debate in terms of outcomes, including perspective taking, student achievement, cognitive reasoning, social support, and interpersonal attraction, with effect sizes ranging from 0.20 to 2.18.

The SAC model differs somewhat from the vision put forth by deliberation theorists. Students may or may not be interested in a particular issue. They are assigned a position, one with which they may personally disagree. Nevertheless, the SAC model embodies essential characteristics of deliberation—focus on a controversial public issue and analysis of different viewpoints and their potential consequences.

Based on theoretical arguments and previous empirical work, this study investigated how student participation in three SACs across six months affected students’ self-reported issue knowledge, perspective-taking abilities, and group variance in opinion.

METHOD

This study used a quasi-experimental research design. After participating in professional development workshops to learn how to conduct classroom deliberations, five teachers led their students through three SACs during a six-month period. Teachers attended three workshops during the academic year to learn, practice, and reflect on the SAC model.

Each Expanding Deliberating in a Democracy (ExDID) Project teacher identified another teacher at their school who taught the same subject and was willing to have his or her students serve as a Comparison Class. Footnote 1 Deliberation and Comparison Classes completed questionnaires prior to and after the three deliberations. The Comparison Classes did not participate in a SAC and neither were their teachers trained in SAC methodology.

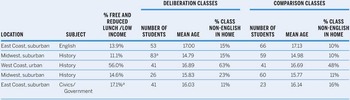

Secondary students (N = 494), ranging in age from 12 to 19, took part in the deliberations; Comparison Classes (N = 493 students) were matched with Deliberation Classes on subject and grade level. This article reflects analysis using two subsets of this population. The number of participating students reflected in the primary finding of the study include only those who responded to the item measuring perspective taking on the post-questionnaire (n = 297 Deliberation students; n = 238 Comparison students). A secondary analysis involved five Deliberation Classes and five Comparison Classes (table 1). Student absences, extracurricular activities, and inclement weather accounted for student attrition.

Table 1 Classroom Profiles

a Combination of two classes, taught by same teacher. The data submitted by the teacher did not allow us to determine which students were enrolled in which class; therefore, we combined the classes.

Classroom Profiles

Students in five Deliberation and five Comparison Classes completed pre- and post-questionnaires (see table 1). Deliberation Classes engaged in a SAC on three issues selected from a list, which included doctor-assisted suicide, compulsory voting, globalization and fair trade, and the limits of freedom of expression.

Data Sources

Student data were collected through pre- and post-questionnaires administered to Deliberation and Comparison students. In addition to basic demographic information, items measured self-reported issue knowledge, student opinions on issues, and perspective-taking abilities.

Issue knowledge was measured by one self-report item (e.g., “I know a lot about this issue”) for each of the three issues. Each statement was connected with the specific issues that the students deliberated. For example, if the students deliberated the issue of a school’s authority to respond to out-of-school cyberbullying, they were asked to indicate their agreement, pre- and post-questionnaire, to the statement with reference to cyberbullying. Students responded to a 4-point Likert scale (i.e., Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree); alternatively, they could respond “Don’t Know.”

Student opinion on issues was measured pre- and post-questionnaire by asking students to respond to three statements, each corresponding to the issues that they studied. For example, regarding the issue of doctor-assisted suicide, students indicated their agreement with the statement: “My country should permit physicians to assist in a patient’s suicide.” Students responded on a 4-point Likert scale, with the additional option of “Don’t Know.”

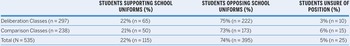

Perspective taking was measured only on the post-questionnaire by having students respond to the following prompts: “Some schools are considering a policy that would require all students to wear school uniforms. What reasons are there to support such a policy? What reasons are there to oppose such a policy?” Students then were asked to indicate their agreement with the policy using a 4-point Likert Scale and “Don’t Know”. We chose this issue because we expected that most students would be familiar with it but would not have given serious consideration to opposing viewpoints. After discarding nonsensical, redundant, and/or illogical reasons, we calculated two scores: the number of arguments students offered in support of (1) their personal opinion and (2) the opposite opinion (inter-rater agreement = 92%). Both scores are important, but we considered the ability to identify rationales for an opposing position to be a marker of perspective taking.

FINDINGS

There was no statistically significant change in Deliberation Class or Comparison Class students’ self-reported issue knowledge. However, Deliberation students demonstrated a significantly higher level of perspective-taking skills than Comparison students, and Deliberation Classes showed less variance in opinion than Comparison Classes after the deliberations.

It is not surprising that the majority of students (i.e., 73.8%) in both the Deliberation and the Comparison Classes did not favor mandatory school uniforms (table 2). Their reasons frequently focused on individual rights of expression and their need to feel comfortable. However, the Deliberation students were significantly more likely than Comparison students to identify reasons for the position that they did not support (p = 0.001). For example, a Deliberation student who did not believe her school should mandate school uniforms was likely to give more reasons why someone might favor such a policy (e.g., “discourages social grouping” and “promotes sense of harmony”). Deliberation students also identified more arguments for their own positions than Comparison students (p = 0.002).

Deliberation students demonstrated a significantly higher level of perspective-taking skills than Comparison students, and Deliberation Classes showed less variance in opinion than Comparison Classes after the deliberations.

Table 2 Student Support for School Uniforms, by Group

Deliberation and Comparison students found more reasons to support school uniforms even if they personally opposed mandating uniforms (table 3). Students who personally opposed school uniforms found more reasons to oppose the policy than those who either supported school uniforms or were not sure of their opinion.

Table 3 Mean Number of Reasons to Support or Oppose School Uniforms, by Student Position

Across Deliberation and Comparison Classes, there was a range of opinion about the three topics before and after the deliberations. A review of the agree/disagree divide reveals that the lowest percentage of students who held one opinion across classes was 18%. Although 18% is clearly a minority, it is also a substantial minority. Across classes and topics, regardless of the position that students took in the classroom, there were peers who supported their position.

The variance in students’ opinions on the pre-questionnaire was similar in Deliberation (i.e., 4.04) and Comparison (i.e., 3.55) Classes; however, after the deliberations, the variance in students’ opinions in the Deliberation Classes narrowed considerably. In other words, the Deliberation students were much more likely than the Comparison students to converge around a position. Post-questionnaire variance for the Deliberation group was 2.29 and for the Comparison group was 3.85 (F (1,609) = 20.786, p < 0.001; Levene’s test). Race/ethnicity, level of parental education, and self-reported grades did not significantly affect students’ movement toward the majority position in the Deliberation Classes.

However, in Deliberation Classes with 60% or more of students agreeing with a position, females and those who did not speak English at home were most likely to move toward the majority position. We were intrigued by these findings and engaged in further analysis. Both pre- and post-questionnaires included a conflict-avoidance measure, so we investigated the relationships between both gender and language spoken at home and students’ tendencies to be more conflict avoidant. The conflict-avoidant measure consisted of three questions answered on a 4-point scale, with an alpha of 0.805. Footnote 2 Chi-squared tests revealed no statistical significance for either gender or language spoken at home. We are unclear about why females and students whose home language is not English were more likely to move toward the majority position; however, it does not appear to be due to a desire to avoid conflict.

DISCUSSION AND SIGNIFICANCE

Our findings indicate that open discussions about relevant political issues in classrooms can positively affect students’ perspective-taking abilities. Similar to Johnson and Johnson (2009), we found that Deliberation students demonstrated greater perspective-taking skills than Comparison students. In Johnson and Johnson’s studies, however, students were asked about topics that they had studied. The positive results in our study suggest that participation in a SAC had a transfer effect relative to perspective taking.

Given the potential for ideological diversity in classrooms, it is important that students can participate in open dialogue with others with whom they disagree.

The ability to identify rationales for positions with which one disagrees, in particular, is critical in a democracy. If students can identify legitimate rationales for positions in opposition to their own, they have at least started to understand the nature of the controversy, to understand that reasonable people can disagree. Given the potential for ideological diversity in classrooms, it is important that students can participate in open dialogue with others with whom they disagree. They also may develop a better understanding of their peers, as well as recognition of the role that individuals’ unique experiences play in the development of opinions. This can lead to a better understanding of why people hold the positions that they do, without the demonization of the other.

Deliberative theorists may look favorably on the statistically significant decrease in variance in Deliberation students’ opinions. Citizens must be able to uncover areas of agreement (and disagreement) after deliberating an issue to take action. This does not mean unanimity of opinion but rather that after deliberation, there is some shared understanding. Our findings indicate that the SAC model may help students learn how to identify and pursue solutions palatable to the majority of the deliberation participants. Future research should assess whether participants moved toward the developing majority viewpoint because they were convinced by arguments and evidence or because they felt pressure to conform.

Although we initially were surprised that Deliberation students did not report greater issue knowledge, we identified three possible explanations for the lack of significant change. First, after studying a topic, perhaps students recognized the complexity of the issue and how little they actually knew about it. Therefore, they may have disagreed with the item “I know a lot about this issue” before and after the deliberations, even though they had increased their knowledge about the topic. For the same reason, they may have agreed at first and then disagreed after the deliberation. Finally, they may have agreed on pre- and post-questionnaires because they had prior issue knowledge. A stronger measure of student knowledge might ask factually based questions about issues. In addition, in studies that have shown increased knowledge after deliberation, participants responded soon after the deliberations (Barabas Reference Barabas2004; Fishkin n.d.). In our study, responses often were given several months after a specific deliberation.

One finding that should not be overlooked is that in all classes, there was a diversity of opinion prior to deliberation. No one student was alone in his or her viewpoint. This is significant because previous studies indicate that students are concerned about expressing unpopular views in class (Flynn Reference Flynn2009; Hess Reference Hess2009). If teachers can make students aware of the diversity of viewpoints in their classes (e.g., through anonymous polls prior to discussion), students may feel more comfortable expressing minority opinions.

CONCLUSION

Classroom discussion of controversial issues is advocated by civic education scholars (Hess Reference Hess2009; Parker Reference Parker2010) as a means to develop citizens’ abilities to engage with one another in a diverse, pluralistic democracy. Our study suggests that there is diversity of opinion in classrooms, a resource that should be utilized by teachers. Our data indicate that across schools with very different student populations, SAC had a positive impact on students’ perspective-taking abilities. Indeed, in a society in which political talk in the media is characterized by vitriol, SAC may be a worthwhile pedagogical tool for promoting greater understanding across political perspectives. v