Introduction: Two scenarios and a framework

In June 2019 the UK became the first major economy to commit to a legally binding target of zero net greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050. Since then the EU, Japan and Korea have followed suit, President Biden has rapidly but as yet informally committed the USA, and China has set a target for ‘climate neutrality’ by 2060. A recent audit of countries, states, regions and cities finds net zero targets in place covering 61 per cent of global GHGs, two thirds of global GDP and 56 per cent of the world’s population (Oxford Net Zero, 2021).

This is promising, but converting targets into outcomes is a much more difficult process. The Paris Agreement of 2015 requires all signatory states to publish Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to decarbonise their economies, to be reviewed downwards every five years (starting in Glasgow in 2021). The current pledges when added together are quite inadequate to achieve a target of 2°C global heating, let alone 1.5°C. By the end of the century we are currently heading for at least 3°C, an unmanageable disruption to global climate.

A growing number of countries have enshrined these policies in new legal and institutional frameworks, pioneered by the UK Climate Change Act 2008. The UK’s Climate Change Committee (2020) has set a tough Sixth Carbon Budget for 2033-37 and the EU has set more stringent interim targets for 2030. Announcing the net zero target the UK government boasted that ‘the UK has already reduced emissions since 1990 by 42 per cent while growing the economy by 72 per cent’. But of course this refers to territorial emissions, not those embodied in the goods we consume. Like most countries in the global North the UK has exported production and GHG emissions to the global South. After falling during the financial crash 2007-09 UK consumption emissions have flattened out at a level over half as high again as our territorial emissions with no significant reduction in sight.

For these and many other reasons net zero targets must be examined critically. And this still leaves out (as I will in this article) all other dimensions of the ecological crisis such as the unprecedented loss of biodiversity and critical drivers such as material footprints. This is the global and national conjuncture within which the rich nations should examine and reconceive their ‘welfare states’. In my book I distinguish three meta-strategies to achieve this shift in the global North (Gough, Reference Gough2017b):

C1. Green growth: decouple emissions from all forms of economic and social activity.

C2. ‘Recompose’ consumption: reduce consumption emissions by switching from high- to low-carbon goods and services, without necessarily cutting overall consumption expenditure.

C3. Degrowth: reduce then stabilise absolute levels of consumer demand, moving towards a steady state economy.

This article looks only at the first two stages, so will ignore questions raised by postgrowth scenarios for a sustainable welfare state, discussed by other contributors. It is quite possible that the first two strategies could fail to improve, or even undermine, human wellbeing, especially of vulnerable people and regions, and thus worsen inequality. So we must investigate the potential routes to, first, fair green growth, and second, fair recomposition of consumption. The two scenarios discussed in the following article can be characterised as 1. Green New Deal + Universal Basic Services, and 2. Towards an Economy of Egalitarian Sufficiency.

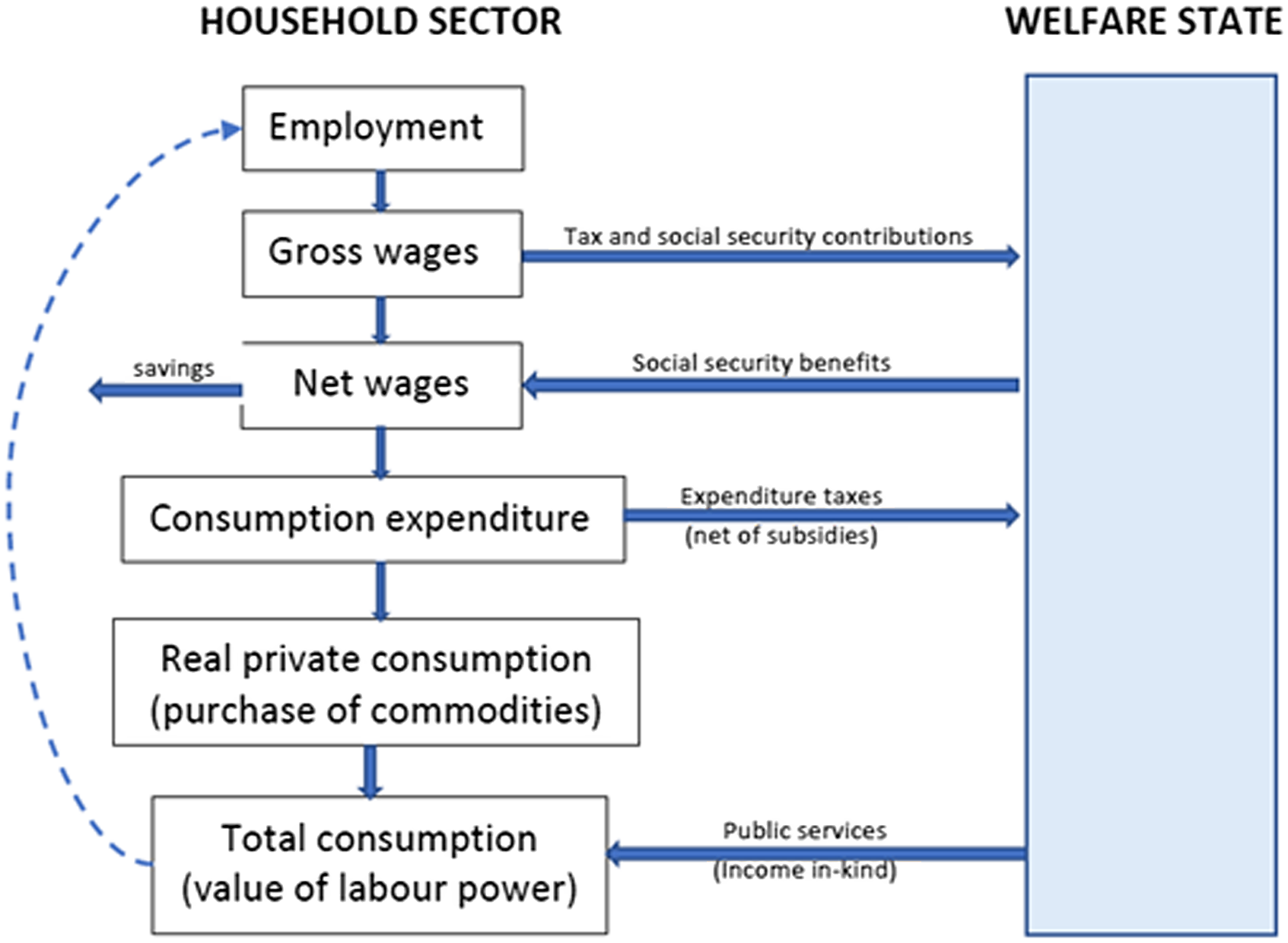

To clarify some implications of these transformations for the ‘welfare state’ I utilise an earlier political economy analysis of the way the welfare state influences the reproduction of labour power and the value of labour power (Gough, Reference Gough1979). The tax system and the welfare state modify the transformation of labour and wages into final real living standards, which then feeds back to the employment and productivity of labour in the process of production. Figure 1 tracks the monetised resource flows between the household and state sectors in a capitalist economy, showing how employment that generates wages is then modified by the tax and welfare state to generate final levels of consumption or real income.

Figure 1. Household sector – welfare state flows (simplified)

Modified from Gough, Reference Gough1979, Table 6.1, Figure 6.1, pp. 109, 115.

The framework takes account only of paid labour and ignores the domain of unpaid labour, also crucial for the reproduction of labour power. In addition, the ‘welfare state’ consists of many other state interventions that legislate, regulate, set standards and so on which constrain private actors and profoundly affect the wellbeing of groups and individuals. But the modification of resource flows in the labour market and household sectors remains a central role of the welfare state.

This modification takes place not only via taxes and social benefits, but crucially also by state provided services in kind. These state services are directly consumed as use values. They constitute ‘collective consumption’ and are conceptually distinct from the use of cash benefits to purchase commodities. This distinction informs the case for Universal Basic Services, discussed below.

Scenario 1: GND + UBS

Calls are growing, for example across the EU, for a new ‘social-ecological contract’, to extend the traditional idea of a social contract. What does this entail? I will discuss in two parts: the ecological and then the social.

Green New Deal

It is helpful to distinguish Green New Deal from Green Transition and Just Transition. A Green Transition envisages a decarbonised economy to a) reduce carbon and GHG emissions, and b) enhance carbon and GHG sinks. In addition, ideas of a Just Transition address seriously the social impact of such restructuring on hard-hit sectors, workers and communities that would lose out, such as mining and fossil fuels. In Europe this is known as the ‘no one left behind’ clause.

Green New Deal (GND) plans and programmes come in many shapes and sizes but they all recognise and foster synergies between safer climate and better welfare. All seem to promise a more integrated programme of environmental and social actions: ‘eco-social policies’ explicitly intended to enhance both welfare and sustainability. While recognising the job losses that stem from switching from a fossil fuel based to a renewable based economy, they all emphasise the opportunities for green jobs and for secure, long-term socially valued employment. Most conclude that net employment will increase during the transition (Tooze, Reference Tooze2021).

Around this core, there are national and regional variations. For example advocates of GND in the USA include a national health service and family benefits, programmes largely taken for granted in much of the OECD world. The EU Green Deal ‘vision’ includes a net zero Europe by 2050, tackling biodiversity loss, a significant investment in the circular economy, ambitious plans for new green jobs, specific plans for housing, transport, agriculture and land, funds for vulnerable regions and much more. Yet it is surprisingly thin on the ‘social arm’, limiting proposals to better education/training and targeted protection for threatened communities. As Sabato and Fronteddu (Reference Sabato and Fronteddu2020) note, there is little on social rights, the Sustainable Development Goals or the EU Social Dialogue.

Current plans for GND have inevitably been over-taken by the global Covid pandemic, the global lockdowns and the need for an economic recovery plan, as illustrated by the Biden $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan and the $2 trillion American Jobs Plan. The Green Deal commits the EU to an immense ‘climate friendly’ investment plan of €1 trillion over ten years. In addition the European Central Bank will provide for another €2.6 trillion over the next decade via an Asset Purchase Programme.

Thus heavy upfront investment is key to all GND proposals. It represents a major switch from previously relying on carbon pricing, regulation and behaviour change (Pettifor, Reference Pettifor2019). There is a clear awareness that carbon pricing is almost always regressive, bearing more harshly on lower income households and localities and that this can encourage anti-climate movements such as the gillets jaunes protests in France. Similarly the idea that ‘losing’ households or communities can be compensated through cash benefits is mostly discredited (Gough, Reference Gough2017a, 2017b).

The consequent reliance on upfront investment will in turn require a radical reform of fiscal frameworks, including much greater state borrowing, a Green Investment Bank and potentially ‘Green Quantitative Easing’, though the last is the subject of heated debate at present (Pettifor, Reference Pettifor2019; Hines, Reference Hines2021). This opens up interesting questions about the historic conjuncture: Does it spell the end of the neoliberal era? Does the Next Generation EU programme signify a ‘Hamiltonian moment’ for the EU – a parallel to the 1790 compact in the US that enabled debt to be the catalyst for a stronger federal centre and deeper continental union? (Kaletsky, Reference Kaletsky2020). Unfortunately, they cannot be addressed here.

A Social Guarantee

The overarching goal should be to match respect for environmental limits with a new social contract (Shafik, Reference Shafik2021). One source for this is the 2016 declaration of Sustainable Development Goals. At the European level the European Pillar of Social Rights could be revised and repurposed (Ferrandis and Alonso, Reference Ferrandis and Alonso2020). An eco-social contract would require addressing existing deficiencies in the welfare state and facing up to new shifts in technology, demography, inequality, and ecology.

A new UK campaign for a Social Guarantee claims to address these new sources of insecurity: to ensure every person’s right to ‘life’s essentials’: education, health and social care, a decent home, childcare, nutritious food, clean air and water, energy, transport and access to the internet (www.socialguarantee.org – see the chapter by Anna Coote (Coote, 2021) in this themed section for details). Referring back to Figure 1, the Social Guarantee can entail policy interventions in four domains:

-

Employment: Job Guarantees

-

Pay: Fair Wages and Minimum Wages

-

Cash benefits as-of-right: Guaranteed Minimum Income schemesFootnote 1

-

In-kind benefits: Universal Basic Services (UBS)

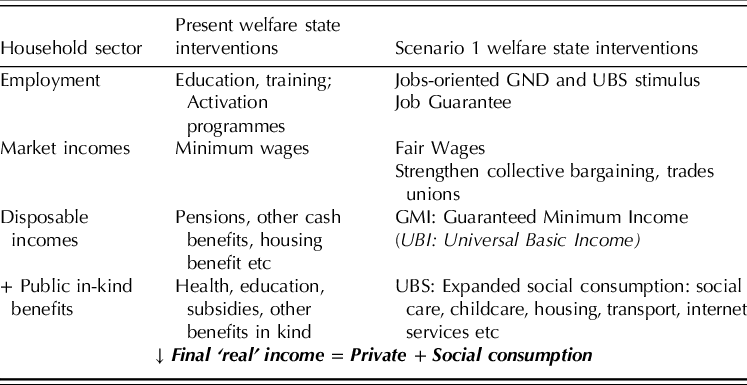

Table 1 illustrates, alongside examples of existing social policies, a range of radical new policy proposals.

Table 1 Scenario 1 welfare state interventions (examples)

All four sets of interventions are necessary and all have supporters and critics but I concentrate solely on proposals for UBS here. This is because UBS directly addresses issues of sustainability alongside just redistribution: it proposes a set of proactive, integrated ‘eco-social’ policies. It thus provides a ‘social’ counterpart to the environmentalism of GND.

UBS

Proponents of Universal Basic Services advocate a wider range of free or subsidised public services enabling every citizen to meet their basic needs and achieve certain levels of security, opportunity and participation. In many countries, public health services and schooling through to higher education are founded on these goals, despite cuts, attacks, and ongoing disputes over principles. UBS proposes to extend these principles to other basic necessities, such as housing, care, transport, access to the internet (IGP, 2017). The normative justification is the superior potential of UBS to secure human flourishing via greater equality, efficiency, collective solidarity and long-term sustainability (Gough, Reference Gough2019b; Coote and Percy, Reference Coote and Percy2020; see Coote, 2021 in this themed section).

First, tax-financed social consumption such as health services, social care and education is inherently redistributive: allocation according to need, risk or citizenship, not market demand, automatically serves redistributive social goals – even when the tax system is neutral rather than progressive. An earlier OECD study found that existing public services are worth the equivalent of a huge 76 per cent of the post-tax income of the poorest quintile compared with just 14 per cent of the richest. Public services also reduce income inequality by between one-fifth and one-third depending on the inequality measure (Verbist et al., Reference Verbist, Förster and Vaalavuo2012). Free or low-cost provision of necessities automatically targets lower income households without the disincentive effects that often result from money transfers.

At the same time, research suggests that the integrated public provision of certain services is environmentally more sustainable. For example, the per capita carbon footprint of health care in the USA is between two and three times greater than in the UK and European countries (Pichler et al., Reference Pichler, Jaccard, Weisz and Weisz2019). This is likely due both to the greater macro-efficiency and lower expenditure shares of comprehensive national health systems and to lower emissions per pound or euro spent, due to better allocation of resources and procurement practices. Reliance on market-steered systems generates duplication and waste alongside profound health inequality. The energy and emissions case for collective provision is even stronger in the transport and housing sectors, as is now recognised by climate science (Ivanova et al., Reference Ivanova, Barrett, Wiedenhofer, Macura, Callaghan and Creutzig2020; Millward-Hopkins et al., Reference Millward-Hopkins, Steinberger, Rao and Oswald2020).

Clearly housing, care, learning and transport, while all essentials, are very different things, so there can be no uniform formula to implement UBS. But entitlements to certain levels of provision can be guaranteed and these can be backed up by a menu of public interventions, including regulation, standard setting and monitoring, taxation, and subsidies. Direct public provision will also be required, but UBS envisages a plurality of collective and communal providers with appropriate support from government.

Substantial UBS programmes can be undertaken at the level of cities and other decentralised authorities, unlike cash transfer programmes that tend to be financed and administered at central level. Local governments can more effectively achieve horizontal coordination across economic, social and environmental agencies: eco-social programmes are now emerging, for example in Leeds and the London borough of Camden in the UK. UBS can combine the vertical and horizontal coordination required for an effective eco-welfare state (Franzoni and Sánchez-Ancochea, Reference Franzoni and Sánchez-Ancochea2016).

GND+UBS would entail increased commitments to public spending. Part of this would be capital expenditure on updating and improving existing physical and social infrastructure, the finance of which will require increased borrowing and bond finance. Current expenditure could in principle be financed through new taxes on (net) wealth, land, data, inheritance, unhealthy consumption, financial transactions and pollution (de Muijnck, 2021). The unifying principle is to extend collective solutions, as opposed to providing income support and leaving provisioning to market forces.

Scenario 2: Towards an economy of egalitarian sufficiency

A scenario such as ‘GND + UBS’ will be at the heart of a sustainable welfare state. But it will not be enough: dilemmas of inequality, consumption and growth will remain. To address these, a second meta-goal will be required in rich countries – to recompose consumption by switching from high- to low-carbon goods and services. I am proposing here a new goal for social policy: to redistribute not just income and wealth but the composition of consumption (Gough, Reference Gough, Meadowcroft, Banister, Holden, Langhelle, Linnerud and Gilpin2019a, 2020b). Raising the share of public consumption via UBS, discussed above, is a vital component of this strategy. In addition I propose that social policy casts a critical gaze on private consumption, which accounts for around 60 per cent of GDP and a still higher share of GHG emissions.

This reflects some profound, indeed tragic, contradictions in the world today. On the one hand, the uneven contribution of national responsibilities for global heating is stark. If all nations are allocated a per capita entitlement to ‘national fair shares’ of energy and emissions, then responsibilities for ‘surplus’ global emissions above this level since 1850 are remarkably skewed according to Hickel (Reference Hickel2020): USA 40 per cent, EU 29 per cent, Russia and rest of Europe 13 per cent, total global North 92 per cent, global South 8 per cent. This distribution of responsibility for climate change is roughly the inverse of where the costs of climate breakdown will land over the next decade. The prior obligations of rich nations to cut emissions and bear the burdens of adaptation and mitigation are agreed by almost all ethical principles. In the second scenario some attempt to redress these global inequalities begins to be made.

Yet at the same time, to take just one example, the purchase of polluting SUVs is rising remorselessly across the advanced capitalist world and among upper income groups in the global South. Between 2010 and 2018, this growing epidemic was the second-largest contributor to global carbon dioxide emissions in the world, behind only the energy industry (IEA, 2021). The surge in ownership of SUVs has more than cancelled out the improved carbon efficiency of the entire car fleet. If the 40 million SUVs in USA were changed for ordinary cars, all 1.6bn people in the world could have electricity without more emissions. This is just one example where the untrammelled pursuit of individual preferences in the context of egregious inequality undermines the goal of meeting common human needs; where economic ‘efficiency’ fatally undermines collective sufficiency.

To buttress these arguments, recent climate modelling shows that a safe climate cannot be achieved by relying solely on pricing and feasible supply-side technologies; there is a growing call for complementary ‘demand-side’ approaches (Creutzig et al., Reference Creutzig, Roy, Lamb, Azevedo, Bruin, Dalkmann, Edelenbosch, Geels, Grubler, Hepburn, Hertwich, Khosla, Mattauch, Minx, Ramakrishnan, Rao, Steinberger, Tavoni, ürge-Vorsatz and Weber2018). One report (Akenji et al., Reference Akenji, Lettenmeier, Koide, Toivio and Amellina2019) estimates the huge shifts in household consumption in developed nations that will be necessary to achieve ‘1.5 degree lifestyles’. Finland’s current GHG footprint – not atypical – would need to fall from 10.4 tonnes CO2e now to 3.2t by 2030, 2.2t by 2040 and 1.5t by 2050.Footnote 2

One demand-side strategy to evaluate transport options, the Improve-Shift-Avoid (ISA) framework, envisages increasingly radical steps from Improve (e.g. switch to electric cars), to Shift (alternative forms of transport, such as walking, cycling and public transit) to Avoid (reducing the overall need for travel via homeworking, online seminars, online shopping, and redesigned towns). The framework is now being applied to other essentials, such as food and housing (Brand-Correa et al., Reference Brand-Correa, Mattioli, Lamb and Steinberger2020). It is clear that this will require a rethink of critical components of private consumption.

Theorising and operationalising sufficiency

The idea of sufficiency has no meaning in orthodox economic theory (Gough, Reference Gough2015). Market demand is driven by consumer preferences backed with money; the theorised goal is individuals maximising utility, or often nowadays ‘happiness’. To make sense of sufficiency requires a distinct eudaimonic conception of wellbeing, one centred around the idea of universal human needs (Büchs and Koch, Reference Büchs and Koch2017; Di Giulio and Defila, Reference Di Giulio and Defila2019). The theory of human need developed by Len Doyal and myself can provide a cross-cultural and cross-generational concept of welfare today (Doyal and Gough, Reference Doyal and Gough1991; Gough, Reference Gough2015, Reference Gough2017b; Steinberger, Reference Steinberger2020). With this theoretical grounding we can expect such needs and need satisfiers to exist in the future. We can envisage what ‘sufficiency’ will mean for our children and future generations. Sufficiency implies a normative rule: sufficiency for all trumps maximisation of utility for some. In an era of extreme environmental stress, sufficiency is also a more precautionary economic rule than maximisation.

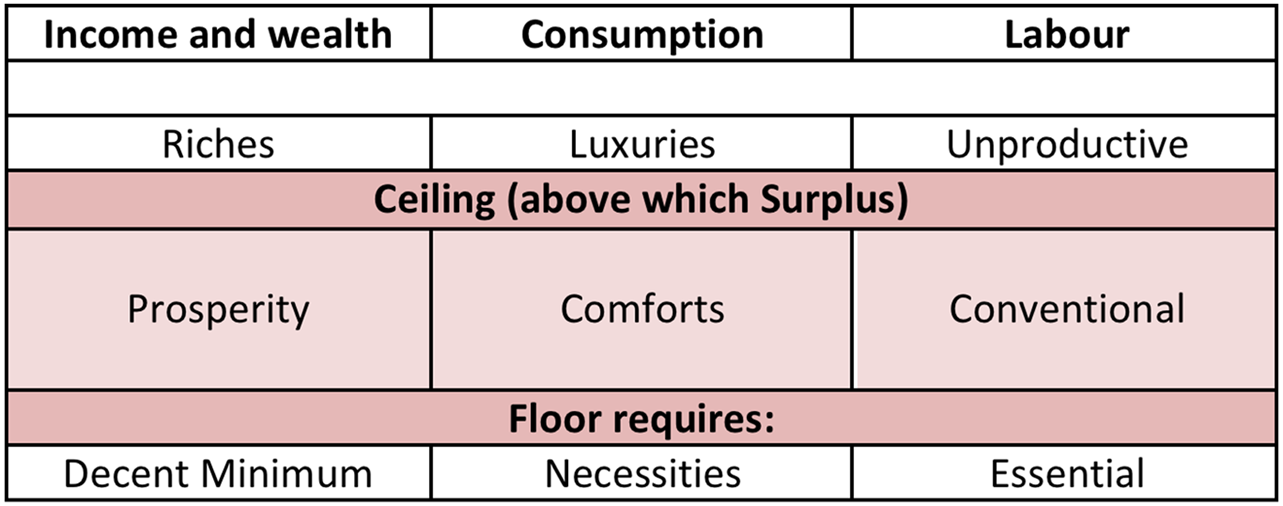

Sufficiency as a new theory of value permits us to distinguish different types of goods and services. To achieve fair recomposition means distinguishing the ‘necessitousness’ of consumer goods and services – whether they are essential, desirable or excessive – alongside their environmental impact. This entails a threefold distinction between necessities, conventional goods and luxuries.Footnote 3 This returns us to the two boundaries – upper and lower – that delimit Raworth’s (2017) ‘safe and just space’ for humanity. It underlies the call of di Giulio and Fuchs (Reference Di Giulio and Fuchs2014) for a sustainable ‘consumption corridor’ between minimum standards, allowing every individual to live a satisfactory life, and maximum standards, ensuring a limit on every individual’s use of natural and social resources in order to guarantee a good life for others in the present and in the future (cf. Fuchs et al., Reference Fuchs, Sahakian, Gumbert, Di Giulio, Maniates, Lorek and Graf2021).Footnote 4

We can generalise this idea from the domain of consumption to the domains of production/labour and of incomes, as in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Floors and ceilings in three domains

Floors refer to the essential labour performed to produce necessities and to generate minimum decent incomes. This is the focus of scenario 1 and the case for UBS. Social policy has a long history in identifying minima and decent standards of living, so will not be examined in detail here.Footnote 5

But to ensure decent standards in a just and climate constrained world requires maxima as well as minima. Ceilings refer to limits:

-

To income and wealth that exceeds any conceivable requirements for human flourishing

-

To consumption of high-carbon luxuries that cannot be generalised to a wider population

-

To labour and employment that hinders provisioning and destroys social value.

Yet to speak of luxuries, riches and limits is to enter disputatious territory. How can such a debate be pursued, let alone consensus be achieved, in a democratic yet hyper-consumption society? Sufficiency movements today increasingly turn to emerging forms of dialogic democracy, such as citizen forums, which bring together citizens and experts in a space as open, as democratic, and as free of vested interests as possible. To operationalise the idea of necessities require a conscious collective process – quite different from the isolated, individual pursuit of choices in markets (Doyal and Gough, Reference Doyal and Gough1991, ch.14; Gough, Reference Gough2017a, 2017b).

Fortunately, we can now draw on the experience of large scale citizen’s climate assemblies lasting six months or more, such as the UK Citizen’s Climate Assembly and the French Convention Citoyenne pour le Climat (https://www.conventioncitoyennepourleclimat.fr/en/). The latter is noteworthy because the French government committed from the start to put forward its proposals for legal adoption – without changes – via referendum, parliamentary vote, or executive order. This is an unprecedented commitment for a citizen’s assembly and makes it a leading example of introducing dialogic democracy into determining climate action, though we should not be naïve about the obstacles on the way.

The French Convention was tasked to decide on policies to achieve a 40 per cent reduction in France’s GHG emissions by 2030. It comprised 150 randomly selected but representative citizens advised by a series of experts and it met over nine months. By the end it had achieved consensus on 149 proposals. Some of these signal a road to sufficiency, including the fast and mandatory retrofit of the least energy efficient buildings by 2030, the implementation of a ban on high-emission vehicles by 2025 (the earliest date discussed by the Convention), a mandate to display GHG emissions on all goods in shops and advertisements, a prohibition on advertising high GHG products, and limits on the use of heating and air conditioning in housing, public spaces and all other buildings. It should be stressed that every recommendation was backed by a consensus of all convention members and that these were representative of all major social, demographic and economic groups in France, including many initially sceptical of climate change. Citizens’ climate assemblies are now developing within many cities and regions across the world. For example in the UK at least 11 councils are now using citizens’ assemblies to drive climate actionFootnote 6 .

Transitional welfare policies for egalitarian sufficiency

This second scenario, to recompose consumption and transit to a more need-based economy, entails a welfare state with broader competencies and powers, though one building on the radical reforms of scenario one.Footnote 7 The strategies advanced in recent literature include the following (Gough, Reference Gough2020b):

-

Implement ceilings on income and wealth

-

Ban, regulate, tax and otherwise disincentivise luxury and wasteful consumption

-

Expand essential public employment and reduce destructive and waste-inducing jobs

-

Cut advertising

-

Reduce hours of work

These ideas can be situated in the analytical framework proposed at the start of this article as in Table 2. Scenario 2 would expand the remit of state action beyond the range of interventions discussed earlier.

Table 2 Scenario 2 welfare state interventions (examples)

It is likely that decisions on the ceilings would begin incrementally and cautiously at first. Some forms of consumption are widely recognized as both ‘luxury’ and high carbon, such as frequent flying (Chancel, Reference Chancel2020). Others, such as ownership of second properties or SUVs would require extensive discussion to establish a consensus for restraint. But it is crucial to recognize that a vast array of ‘non-essential’ but socially important forms of jobs and consumption would continue, from home improvements to holidays, from bars and restaurants to festivals and fun. This is not a recipe for puritanism, as many critics of hyper-consumption agree (Jackson, Reference Jackson2021).

Our approach to floors and ceilings also recognizes that consumption floors reflect social values, social relationships and patterns of activity that differ from context to context. Simply to reduce the floor in the developed world in order to achieve net zero within existing socio-technical structures would deprive citizens of a vast range of goods and services – housing standards, personal transport, a range of clothing, a choice of nutritious diets, and so forth – that current minimum income studies have agreed are necessary for effective participation in modern life (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Hirsch, Padley and Marshall2015). The focus must necessarily be on the excess and dangerous consumption of the rich, starting with the super-rich.

Is it conceivable that the Covid-19 pandemic has facilitated such a shift? In March 2019 the UK and other governments produced a list of ‘essential occupations’ with special privileges during pandemic-related restrictions (Gough, Reference Gough2020a). The UK list extends way beyond health and social care or emergency services, to include farmers, supermarket staff, workers in water, electricity, gas and oil, teachers, telecommunication workers, transport staff, workers in law and justice, religious staff, social security staff and retail banking staff. Other governments produced similar lists: some, such as the Irish, including supply chain workers furnishing inputs to the key workers.

Whether intended or not these lists of occupations signalled a notable shift in official thinking in two ways. First, they questioned dominant neo-classical value theory, where any activity is deemed valuable or productive if it is remunerated, whatever its social value or disvalue. For the first time since the Second World War, governments have been forced to distinguish a subset of useful labour, and implicitly ‘use values’. Second, the evidence of low pay levels for many key workers (IFS, 2021) demonstrated the dramatic gap between market valuation and social or normative valuation of different forms of labour.

Such an explicit valuation of different jobs in the labour market could mark a step forward in sustainable and egalitarian discourse. If it can then feed into a more critical perception of consumption and incomes, as illustrated in Table 2, it would mark a second qualitative step forward for welfare states.

Conclusion

The Anthropocene will likely force some drastic transformations to existing welfare states. I have distinguished two scenarios. The first envisages the widespread uptake of green new deal programmes, which entails a substantial increase in green capital spending both private and public. To ensure an acceptable level of human security and wellbeing through this period of transition a social guarantee should be enacted: an eco-social contract to reform the welfare state. In particular the public and collective provision of essential goods and services should be guaranteed and extended. This combined scenario would reverse the neo-liberal austerity project of the last decade but would not be incompatible with emerging trends in contemporary capitalism.

The second scenario would recognise the extensive and urgent obligations of rich country welfare states to contribute to decarbonisation on a global scale. This would require tackling consumption patterns that are unsustainable, but to do so in a fair way that preserves consumption of necessities and other activities that enhance flourishing. Such an economy of sufficiency would begin to address the ‘ceilings’ of luxury consumption, excessive wealth and unproductive labour.