In May 1947, Fortune magazine asked its readers to “imagine a company” with assets close to a billion dollars “operating on a set of books that would put a country storekeeper to shame.” This was a highly integrated company, employing 130,000 men and turning out a million cars and trucks a year, which possessed “no accurate knowledge of which individual operation was paying its way” and whose management had “no clean lines of authority or responsibility anywhere delineated.” For Fortune’s readers such a company may have been hard to imagine, but it did exist: the magazine was speaking of the Ford Motor Company. Henry Ford had died weeks earlier, and the magazine was covering the efforts of Henry Ford II to sort through “the amorphous administrative mess” his late grandfather had left behind. The origins of the disarray lay in the 1920s, the article said, when under “the sheer ineptitude of Ford management” the company lost its sales dominance to its competitors and stumbled through the 1930s with barely a profit. Now the young Ford was applying strong and salutary medicine to the ailing organization by rebuilding it “in the image of General Motors”: hiring General Motors (GM) executives with the task of establishing a decentralized management structure, subjecting operations to financial controls, and implementing uniform accounting metrics.Footnote 1

Business historians have for the most part agreed with Fortune’s 1947 piece: by the 1920s, the company that had pioneered the mass production of automobiles was losing its grip. The famous Ford Model T was fast becoming obsolete, and the company began staggering toward near-terminal decline thanks to financial negligence, failures in bookkeeping, and inept management. At fault was Henry Ford, who assumed full control of the Ford Motor Company by acquiring all minority stock in 1919. As a result of this decision, business historians have said, the company clung to “an antiquated administrative system totally unequal to the demands of a modern era” under the “personal control of one eccentric individual.”Footnote 2 Under Henry Ford, the company lacked “any systematic organizational structure.”Footnote 3 It suffered “organizational degeneration.”Footnote 4 It was mired in “chaos.”Footnote 5 In passing these verdicts, historians keep the comparison with General Motors close at hand: the implication is that Ford could have avoided its difficulties if it had not waited until after World War II to refashion its management, GM style.Footnote 6

Confronted with such overweening consensus, one wonders how this company survived more than two decades of managerial incompetence without collapsing entirely, let alone how it set production records throughout the early 1920s and again in 1929, how it accomplished engineering feats like the mass-produced V8 engine (1932), or how it became a pillar of the “Arsenal of Democracy” during World War II. That the summary assessment of managerial dysfunction is at odds with a reality of efficient (or at least prolific) operations has been variously recognized.Footnote 7 Research on the Ford Motor Company, however, remains largely reflective of the notion that its founder was both a production genius and an administrative dud. The company's production methods have received detailed scrutiny, but its financial and administrative realities remain almost unexamined.Footnote 8 (Not coincidentally, the inverse could be said of General Motors.)

The purpose of this article is to open the black box of Ford management. After Ford had established his unchallenged authority with the 1919 buyout, how did the company actually operate? This article considers three areas: finance, administration, and shop floor management. As we will see, the company—no longer beholden to outside investors—rejected financial control metrics and procedures of managerial legibility. Instead, Henry Ford turned his company into a mission-driven organization that prioritized production, engineering, and the pursuit of social and political goals over investment returns. Administration followed informal, personal, and flexible routines instead of codified bureaucratic structures. Shop floor supervisors, meanwhile, rejected the methods of Taylor-type efficiency systems and instead relied on ingrained collective protocols and routines based on an intimate familiarity with the production process.

The success of these informal arrangements depended on what one staffer described as Henry Ford's “invisible leadership”; Ford provided, at least to a core group among the administrators and shop superintendents who managed day-to-day operations, the inspiration for a collective ethos of initiative in working for the company.Footnote 9 The Ford Motor Company, in short, was a charismatic organization. This fact accounts for both the company's successes during the 1920s and its resilience despite a crisis of leadership in the 1930s and 1940s.

In invoking charisma here, I intend to return to Max Weber's original formulations of the concept and to highlight four features in particular. First, “charisma” does not designate the qualities of an individual, but describes, as Weber said, a “definite social structure” coproduced by a leader and his or her community. Charismatic authority is fundamentally a collective endeavor; in grouping around a leader, followers constitute a “horizontal” social bond among themselves as much as a “vertical” one between themselves and the leader. Second, charisma is based on a mission that the leader expresses and symbolizes, that endows him or her with legitimacy among followers, and that the followers embrace as a collective purpose. As Weber clarified, not any kind of mission will do; true charismatic authority requires a “revolutionary” mission, one that repudiates established norms and challenges the political and economic status quo. Third, charismatic authority will develop an organizational structure that reflects the collective mission. Charisma is not amorphous; it includes “a staff and an apparatus of services” that is “adapted to the mission of the leader.”Footnote 10 Fourth, as Weber would have insisted, identifying a given social order as charismatic is a value-neutral analytical move. A fool or a genius, a hero or a quack may be a charismatic leader, as long as he or she finds disciples.Footnote 11 Positing the Ford Motor Company as a charismatic organization, then, implies no validation of Henry Ford's ideas (some of which were famously repugnant or misguided), nor is it an attempt to whitewash his labor policies, which were notoriously repressive. Applying charisma to the Ford Motor Company is an attempt, however, to describe the company's management practices in terms that are adequate to their intrinsic logic.

My core contention is that the organizational structure and administrative practices of the Ford Motor Company are best understood as an institutionalized expression of the company's charismatic mission. This mission arose from the social background and skilled-labor ethos of Henry Ford and his staffers. In the company they ran, Ford and his associates sought to give expression and practical validation to their world view, according to which automotive mass production was an achievement of shop floor expertise. On both philosophical and practical grounds, this view challenged two powerful countervailing forces of the era: finance-driven corporate capitalism and the movement of “systematic” shop and personnel management. This contrarian agenda gave Ford's mission its “revolutionary” quality—at least in the eyes of its adherents.

Because a charismatic mission aims at the social and political, the standard vocabulary of market strategy and economic rationality fails to capture it adequately. To say that the Ford Motor Company was a charismatic organization, then, means more than shoehorning the company into familiar firm typologies. One might explain the company's closely held ownership, and its reinvestment orientation, by pointing out that it was a family business.Footnote 12 Alternatively, one could identify Ford as an “entrepreneurial” firm that exhibits features often found among new, technology-oriented companies (a dominant founder, a loyal group of staffers, flexible hierarchies, investments in process innovation, etc.).Footnote 13 Functionalist classifications such as these, however, fail to identify the root origins of Ford's governance structures, which resided in the mission. Charisma, in contrast, emphasizes precisely those (putatively extra-economic) factors—social hierarchies, affective relationships, politics, and ideology—that functionalist theories of organization struggle to capture.Footnote 14 As a social structure, charisma exceeds the boundaries of the market. Charisma, succinctly put, is a sociopolitical phenomenon, not a firm type. A prepossessing leadership style is not charismatic authority; a product strategy is not a charismatic mission.Footnote 15

Using charismatic authority (conceived as a social structure) to understand the Ford Motor Company, then, has several advantages. It dispenses with normative assumptions that equate efficiency with bureaucracy and professionalized management. It allows us to understand the company's administrative structures not as the product of an idiosyncratic personal style, or as chaotic, dysfunctional, and resulting from some failure; rather, Ford management emerges as a coherent system in its own right, one that accorded with the company's mission-driven nature. Charisma draws attention to the social and political, rather than market-internal, nature of that mission. Finally, charisma allows us to shift our focus from the administrative “top” to what Weber called the “charismatic administrative staff”—those responsible for running the company on a day-to-day basis. Since the complement to charismatic rule is not obedience but initiative, such rule can, ironically, largely dispense with the leader's constant supervision, as long as subordinates believe in the mission and act to perpetuate it.Footnote 16

To reconstruct how the Ford Motor Company operated, this article uses two groups of sources. The first is the company's accounting records, which are preserved in scattered and discontinuous form at the Benson Ford Research Center (BFRC) in Dearborn, Michigan. Concerning the administrative practice of the Ford Motor Company, we cannot hope to draw on the usual artifacts of corporate bureaucracy, such as organization charts or annual reports, which the company deliberately did not maintain. Instead, however, we have a comprehensive collection of interviews with former staffers from across the entire Ford organization. In the 1950s, researchers conducted more than two hundred of these interviews in connection with the Ford trilogy by Allan Nevins and Frank Ernest Hill.Footnote 17 The BFRC catalogs these oral histories under Accession 65 as “Reminiscences,” which suggests anecdotal material; however, these materials actually make up a remarkably rich repository of information on company policy, engineering, and shop floor practice, as well as administration, accounting, and finance.Footnote 18

Ford's Mission and His Charismatic Staff

Charisma, understood as a social phenomenon, arises as an insurgency against the status quo. What legitimates a charismatic leader is that he or she symbolizes a credible revolutionary mission.Footnote 19 To grasp Henry Ford's charismatic appeal, therefore, we need to understand what made his mission appear “revolutionary” in the political and social context of his time. As everyone knows, Ford set out to build a sturdy motor vehicle for popular use at a cheap price. In pursuing this vision, the Ford Motor Company perfected production techniques—assembly lines, sequencing of operations, and the scaling up of machine tools—that resulted in unprecedented economies of scale. These allowed Ford not only to pay high wages to unskilled workers but also to lower the price of his Model T while reinvesting the plentiful proceeds into continuous expansion of production.

The annals of automotive history have tended to treat these achievements primarily as a type of innovative business proposition, as though the sole significance of the Model T lay in Henry Ford's intuiting the market potential for a popular car. What made these achievements appear revolutionary to Ford's followers, however, was not primarily their business success, but rather the challenge they put to the social assumptions and political-economic hierarchies of their time. Hindsight obscures the extent to which the Model T was, first, a social provocation. The early automobiles that appeared in America in the 1890s were posh and pricey status symbols customized for the Gilded Age haute élite. These were not “consumer durables” but artifacts carrying a status value perhaps akin to that of the private jet today. In the face of such genteel distinction, the rough-and-tumble Model T thrust the populist proposition that technological innovation and mobility should avail the commoner.Footnote 20

Mass production and the Model T, second, expressed a distinctive view of the political economy. It is too often forgotten that Henry Ford (and his closest associates) hailed from a working-class milieu—that of the mechanics, machinists, and skilled metal workers whose middling shops and producerist culture flourished in the shadow of the large railroad and mining fortunes of the Midwestern elites. Mechanics like Ford acquired expertise through practical on-the-job experience and expected their skills to furnish them with chances for upward social mobility. The mechanics shared the producerist outlook and anticorporate populism that suffused Midwestern politics around the turn of the twentieth century.Footnote 21

As the mechanics who ran the Ford Motor Company saw it, the transformative achievement of automotive mass production came directly from the shop floor. It arose from the technological ingenuity and productive expertise of skilled labor. Mass production and the Model T also seemed to provide tangible proof of a broader conviction: that productive labor was the exclusive basis of social and economic progress. The goal, Henry Ford declared, was “to employ still more men, to spread the benefits of this industrial system to the greatest possible number, to help them build up their lives and homes.”Footnote 22 Charles Sorensen, Ford's longtime production chief, credited Ford with the discovery that growth depended on widely distributed moderate incomes rather than the huge fortunes accumulated by the wealthy. “Higher wages, higher production—this must be the formula,” he recalled.Footnote 23

In Sorensen's telling, this “formula” was the unstated motive behind the Ford Motor Company's landmark innovations: the assembly line system of Highland Park (1913), the five-dollar day (1914), and the steadily declining price of the Model T (from $900 in 1909 to $200 in 1921, in inflation-adjusted dollars).Footnote 24 The “formula” also inspired Ford in 1915 to withhold dividends to stockholders and channel the company's abundant profits into the construction of a new factory (River Rouge). This was the very decision over which Ford's minority stockholders sued, and which in turn prompted Ford to acquire exclusive ownership of his company in 1919.Footnote 25 Sorensen recalled:

To this day I still get a thrill when I review it like I am doing now. It would never have been possible if Henry Ford had listened to his directors and stockholders. They had the profit motive. They would not accept the formula. Profits was their formula. It took five years to eliminate that [1914–1919]. With [their] formula there would be no Rouge plant and all that went with it. Henry Ford saw all this clearly. It was no speculation. Stick to the formula, and he did. Can I make it clear? The formula did it.Footnote 26

Sorensen, a son of working-class Danish immigrants, exemplifies the backgrounds of the skilled mechanics who ran the Ford Motor Company and embraced Ford's producer populism. Sorensen had quit high school in his teens to become a patternmaker apprentice. Like many of Ford's close associates, he joined the company in its founding period and stayed for several decades, working his way up through the ranks. Ford managers were “mechanically minded men without formal education,” mostly first- or second-generation immigrants of northern European descent, who shared an ethos of on-the-job training and practically acquired expertise.Footnote 27

In the words of a former staffer, Henry Ford favored “production men rather than businessmen” and was “never favorable to anything which took on white collar workers.”Footnote 28 While other corporations increasingly put theoretically schooled engineers in charge of their shops and business school graduates into their boardrooms, promotion at Ford came almost exclusively through the ranks. In Sorensen's words, the successful Ford manager was a “specialist but not an expert.”Footnote 29 Ford's production men were joined by clerks with often checkered educational records who acquired the substance of their accounting knowledge on the job.Footnote 30 Both on the shop floor and in the offices, Ford's staff consisted of men whose upward mobility depended on sustained work experience and continued allegiance to the company.

The Ford Motor Company, then, refused to welcome the efficiency consultants and proponents of “systematic” management who increasingly intruded on American factory floors elsewhere.Footnote 31 Unlike other automakers, Ford also resisted a second powerful force transforming the industrial landscape: the influx of outside capital. As Ford was taking his company off the market, General Motors invited the chemical conglomerate DuPont de Nemours, and later the investment bank J.P. Morgan, to obtain substantial stakes. Eventually, these investors took over the corporation and appointed a fresh group of executives to run it (of whom Alfred Sloan would become the most well known).Footnote 32 During the very period that Ford was solidifying his hold over the Ford Motor Company, in other words, other Michigan automakers lost control over their divisions to deep-pocketed eastern investors. In short, in a period when finance capital, white-collar professionalization, and corporate bureaucracy were eroding the stature of the skilled mechanics in American industry, the Ford Motor Company reassured their self-image and reaffirmed their claims to industrial leadership.

A comparison with General Motors might give some clarification of the Ford mission. In his “Product Policy” memo of 1921, GM's Alfred Sloan famously stated that “the primary object of the corporation was to make money, not just to make motor cars.”Footnote 33 In contrast, Henry Ford declared in My Life and Work (1922) that “the primary object of the manufacturing corporation is to produce, and if that objective is always kept, finance becomes a wholly secondary matter.”Footnote 34 In Weberian terms, one might say that the famous refashioning of GM under Sloan expressed instrumental rationality: that is, given the priority of “making money,” what organizational structure and market strategy might best serve that goal? Measured in terms of this declared goal, as is well known, GM was more successful than the Ford Motor Company from the mid-1920s.

What is striking in Ford's statement, in contrast, is that it expresses at once more and less than a business strategy: that production should take priority over finance is both an organizational goal and a normative claim. The Ford Motor Company's organization, then, embodied value rationality: given collective values (a skilled-labor ethos, producerist commitments, antifinance sentiments), what organizational structure and what policies might best give expression to them?Footnote 35 More than anything, this perspective explains the company's oft-criticized decisions, such as the overlong attachment to the one-size-fits-all Model T, and its rejection of managerial bureaucracy. It helps explain, too, the company's jaundiced view of advertising, product embellishment, frequent model changes (or, planned obsolescence), and consumer credit. The trajectory of the Ford Motor Company after 1920, so puzzling when measured in Sloan's terms, looks much less bizarre and actually quite coherent once we factor in the producer orientation and value-based denigration of finance at the core of the company's mission.

As is well known, Henry Ford used his newfound prominence after the five-dollar-day sensation to embark on a series of highly visible political forays, such as the ill-fated “Peace Ship” expedition of 1915; an antiwar campaign at home that earned him the unlikely epithet of “anarchist” from the Chicago Tribune (Ford sued for libel and won); the bid for the government complex at Muscle Shoals; and, most notoriously, the lurid anti-Semitic campaign of the Ford-owned Dearborn Independent. These efforts increased public awareness of Ford's political ambitions outside of the company, where they had previously been seen as broadly consistent with several Populist tenets—with isolationist preferences, skepticism of financial elites, and a pronounced susceptibility to conspiracy theories.Footnote 36

Did staffers share Ford's politics? What role did anti-Semitism play in the charismatic dynamic? Two of Ford's closest associates—company philosopher William Cameron and Ford's factotum Ernest Liebold—were directly involved in launching the Dearborn Independent. They also clearly shared Ford's anti-Semitism.Footnote 37 Midlevel staffers outside of Ford's inner circle appear more divided though hardly opposed to Ford?s prejudices. Sales manager H. C. Doss, for example, endorsed the Independent’s campaign but added that “it certainly didn't help business.”Footnote 38 Herman Moekle, chief accountant, said that he “never had anything to do with the Dearborn Independent” but felt that the campaign “would tie in to a certain extent with [Ford's] distaste of Wall Street” and his belief “that any manipulation of business interests from the money standpoint was wrong.”Footnote 39

In short, for some of Ford's staffers, anti-Semitism appears to have been an important part of the collective value system; for others, it is less clear. By and large, staffers accepted Ford's anti-Semitism as part of the mission, but few seem to have based their affective identification with the company exclusively on it. In the day-to-day task of running the company, other issues mattered more. What primarily galvanized Ford's administrators and shop-level machinists was the company's culture of practical expertise and collective achievement in furthering “the formula”: a commitment to technology, engineering, and production, which emerged from the shop floor, remained unperturbed by financial priorities, and was immune to the pretensions of outside professional expertise.

A Mission-Driven Organization: Finance and Accounting

After the 1919 buyout, the Ford Motor Company reinvested most of its earnings, sustained operations that the founder favored even when they were unprofitable, and made decisions on capital outlays not on the criteria of investment returns, but on whether the expenditure furthered research, improved production, or propagated the producerist cause. This was possible for two reasons: first, as a privately held company, Ford could afford to eschew the type of strict financial oversight and budgetary planning generally required by outside shareholders; second, thanks to the Model T windfall and the early success of the Model A, the company had at its disposal ample funds that it did not come close to exhausting, even during the depressed 1930s. In this sense, the Ford Motor Company behaved much like a nonprofit boasting a substantial endowment.Footnote 40

Freed from the need to satisfy outside shareholders, the company embarked on a robust policy of reinvestment. Before the buyout, the Ford Motor Company distributed an annual average of 44.75 percent of net earnings to stockholders.Footnote 41 In the two decades after the buyout, which included the most profitable years in the first half-century of the company's existence, the level of distribution was 24.78 percent; in an instructive comparison, over the same time period, GM paid out 77.86 percent of its net earnings.Footnote 42

As a result, the company accumulated formidable liquid reserves during the 1920s. Again, a comparison with General Motors is revealing: even as GM surged ahead in earnings, Ford's absolute cash position remained stronger than that of its rival throughout most of the interwar years (Figure 1). Along with Ford's decision to shun the burgeoning capital markets of the 1920s—the company refrained from borrowing, or issuing new stock—its cash position not only allowed the company to stay solvent during the income-starved 1930s, but actually gave it enviable operational independence. Ford's single strength, Fortune acknowledged in its 1947 piece, was that the company was “still solvent from the fruits of the fat years,” with a treasury of “almost $300 million in cash.”Footnote 43 What was more, “the Company didn't owe a cent.”Footnote 44

Figure 1. Ford Motor Company and General Motors Liquid Assets, 1920–1939. (Sources: Ford and GM balance sheets as listed in the annual issues of Moody's Analyses of Investments and Securities Rating Service: Industrial Securities [New York, various years].)

These figures, however, understate the degree of reinvestment, since the Ford family's dividend earnings often redounded to the larger organization. During the 1920s, the company expanded rapidly, as it branched into subsidiary operations such as coal mining, lumbering, shipping, aviation, and railroading. In setting up these operations, Henry or Edsel Ford frequently forwarded the necessary funds from their private accounts. For example, when the company acquired the Detroit, Toledo & Ironton Railroad in 1920, Henry Ford bought the shares and assumed the road's substantial bonded debt. Ford's executive recalled that, in order to keep the road operating, “why, I advanced the money from Mr. Ford's funds for the payrolls and such other expenses as they required.”Footnote 45 In keeping with this practice, Ford's accountants upheld the separation between the books of the Ford family (as stockholders) and the books of the company primarily for legal and tax purposes. In practice, they assumed that company and family funds overlapped, and acted accordingly.Footnote 46 By these informal arrangements, dividends remained part of the funds of the greater Ford organization.Footnote 47

How the company maintained its subsidiaries also reflected the centrality of its mission. Subsidiaries often combined philanthropic or developmental aims with production purposes. The so-called Ford Village Industries, for example, produced small parts—spark plugs, axles—for shipment to the Rouge. Constructed in state-of-the-art modernist architecture and taking advantage of water power, however, these factories also were experiments in decentralized industrial activity meant to offer year-round employment to rural areas.Footnote 48 Subsidiaries such as the village industries were expected to produce efficiently, but they did not keep their own profit and loss accounts. Rather, “any expenses incurred by them were paid by the Ford Motor Company.”Footnote 49 Between 1921 and 1946, the company operated on a “single-entry branch accounting system” that centralized control in Dearborn.Footnote 50 Subsidiaries were “paper corporation[s],” whose expenses factored into the overhead of the parent company.Footnote 51 As outfits with experimental, developmental, or social purposes, these subsidiaries were not operated to be profitable and often failed to cover their own costs. Rather, the parent company funded subsidiaries, profitable or not, as long as they advanced the company's mission. In other words, the company's mission-centered modus operandi explained the seeming laxity that prompted Fortune’s headshaking remark that headquarters was not able to tell “which operation was paying its way.”

The necessity for sharp accounting was further attenuated by the company's large liquid funds. As one of the company's chief accountants recalled, for the large expansion of the 1920s “no master plan was ever drawn up from a financial standpoint.” Instead,

it was a question as to whether or not the particular development was a desirable thing, whether it would promote the business, whether it would do something better at the time than was being done prior to that time. If it was considered to be that in the opinion of Mr. Ford's advisers and Mr. Ford agreed with them, why, they went through with it.Footnote 52

For example, in Sorensen's telling, the landmark River Rouge steel mill resulted not from market analysis or ponderous cost-benefit accounting, but from the production needs of the company and the perceived monopoly behavior of outside suppliers. For steel,

in the period of 1919 to 1929 the demand exceeded the supply. We were tearing our hair. The profit motive seemed to interest steel-makers more than increasing facilities. It was evident somebody had to add facilities. We decided to make steel, just as simple as that, after we had been driven to it. When I produced a plan of a steel mill . . . and showed it to Edsel and Henry Ford and told them it would cost $35,000,000, there was not the least hesitation on their part. Henry Ford's reply to the proposal was, “what are you waiting for?”Footnote 53

Leaving room for hyperbole, we can take this anecdote as sufficiently illustrative of both the financial strength and the informal budgetary practices of the Ford Motor Company in the 1920s.

Noncodified Routines: Ford's Inner Circle and His MidLevel Administrators

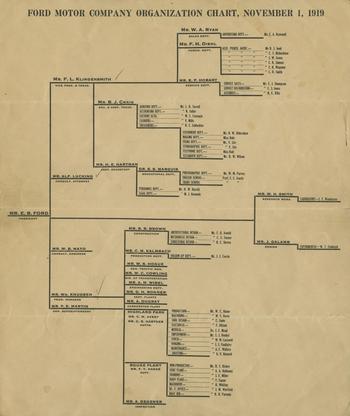

Ford's buyout of minority stock, then, had momentous consequences in the financial sphere. Less well known, but equally consequential, was Ford's simultaneous decision to reject the administrative recommendations of management consultants. In 1919, the New York efficiency firm Thompson and Black, originally hired to orchestrate the buyout, produced a chart that sought to clarify the company's organizational structure (Figure 2). It would remain the only such artifact in the company's history before the end of World War II.

Figure 2. “Ford Motor Company Organization Chart, November 1, 1919.” The company's last organization chart before 1946. (Source: Photo ID#84.1.1660.P.D.311, acc. 1660, box 37, folder 6, Benson Ford Research Center, Dearborn, Michigan.)

The chart was a typical exemplar of the kind of administrative flowcharts popularized by Progressive-Era “systematizers” of management. Speaking in terms of classical organizational theory, it depicted a centralized, functionally departmentalized business. However, as will become clear presently, the chart misrepresented the administrative realities of the Ford Motor Company in crucial ways. First, it suggested self-contained offices with mutually delineated spheres of authority; in reality, Ford staffers habitually moved among several spheres of competence at once. What responsibilities separated “production manager” Knudsen from “general superintendent” P. E. Martin remained unclear in the chart—a telling concession to the reality that the two men operated in close contact and were seen to share authority at Highland Park. Second, the chart failed to account for the routinized close coordination between separate company spheres. It attempted to distinguish financial authority (under Klingensmith) from operations (under Knudsen and Martin), a separation entirely spurious for the Ford Motor Company. For example, the chart gave no sense of the intimate contact between the Highland Park shop floor and the purchasing department.Footnote 54 Finally, several names were conspicuously absent from the chart: precisely those staffers whose authority cut across the organization, such as Sorensen, Liebold, and, of course, Henry Ford.

In short, the chart drawn up by Thompson and Black constituted a heroic and failed effort to make the company's flexible and informal administrative structures legible to the logic of “systematic” management. In April 1920, Ford ordered the chart scrapped, reasoning that it was “too confusing to the men” and “too military.”Footnote 55 In My Life and Work, Ford elaborated that he had no patience for “excess organization and red tape” of the type that “results in the birth of a great big chart showing, after the fashion of a family tree, how authority ramifies.” Instead, Ford claimed, the company had “no organization, no specific duties attaching to any position, no line of succession or of authority, very few titles, and no conferences.”Footnote 56

Brash though it may seem, this description appears to have been largely accurate: a pervasive antibureaucratic ethos pervaded the day-to-day administrative practice of the Ford Motor Company. Clerical paperwork was strictly subordinated to the needs of the shop. Coordination proceeded through informal and implicit hierarchies based on personal relationships. Spheres of responsibility were not codified and compartmentalized, as the 1919 organization chart suggested; rather, they resulted from spontaneous delegation, independent initiative, institutional habituation, and informal cooperation. Company procedures were governed by “unwritten laws.”Footnote 57 No organization chart was necessary, because, as one clerk put it, “it was generally known who was in charge of what.”Footnote 58

The antibureaucratic ethos animated both the company's upper administrative echelons and its midlevel office personnel. In legal terms, the Ford Motor Company after 1920 was a Delaware corporation, with the three stockholders—Henry, his wife, Clara, and their son, Edsel—listed as directors, and Edsel acting as company president. In practice, however, the corporate form meant very little, as meetings of the board were a “formality only” and minutes were drawn up simply “to comply with the law.”Footnote 59

Strategic policy did not originate in formal deliberations, but rather bubbled up from among a group of close associates that staffers further down the line referred to as “Mr. Ford and his immediate advisors.”Footnote 60 Membership in this group fluctuated over time and depended on whose ear the founder had in any given matter. Core members, however, included Martin and Sorensen, in the production sphere; Edsel, who oversaw administration and finance; and Liebold, company secretary and Ford's appointee for special tasks. In the 1930s, much to the vexation of Ford's other associates, this group was increasingly dominated by Harry Bennett. Since Henry was loath to involve himself in day-to-day administration, he relied on this group of executives to run the company for him.

Rarely did Henry Ford issue a proposition of his own; rather, his lieutenants presented ideas to him. This sometimes required an active anticipation of the founder's wishes. “I could sense what he wanted and I did not need to be told what to do,” recalled Sorensen.Footnote 61 Henry, in turn, gave his lieutenants the implicit authority to proceed in whichever ways they considered proper. This dynamic of authority delegation jibed with noncodified spheres of competence: getting a job done might require short procedures. “When I had charge of production,” Sorensen recalled, “I could advise, check up, or dip into the treasurer's affairs, watch capital investments, and hold up what expenditures I felt were unnecessary.” He felt that “anyone who had Henry Ford's confidence had the same privileges in his field that I had in mine.”Footnote 62 This dynamic of subordinate self-initiative resulted in the fact that the founder's decision—which was beyond dispute—frequently appeared in the form of a veto (as, for example, in the case of the withdrawn organization chart). Such periodic vetoes would then reestablish the course as the founder saw it.

Conspicuous in the company's administration was the role of “special-assignments man” who “reported directly to Henry Ford.”Footnote 63 Such plenipotentiaries were seen to wield Ford's directly delegated authority and hence had the power to circumvent established company channels, recruit company resources, or appropriate necessary funds for appointed tasks. For example, Ford put Liebold in charge of the Detroit, Toledo & Ironton Railroad, instructing him to proceed as he saw fit. Liebold refashioned the railroad in keeping with the company mission. He lowered freight rates by 20 percent, raised wages to the uniform Ford six dollars a day, abolished organizational titles, and revised administration “so we could get along with the least amount of book work and bookkeeping that was necessary.” Liebold recalled his pride in having the founder's backing in these activities, an experience he described as having “carte blanche.”Footnote 64

To Liebold's great satisfaction, the refashioned railroad began to operate profitably despite higher wages and lower freight charges. He concluded his recollections with these words:

No great mind was responsible for the results beyond the general supervision and advice of Mr. Ford. . . . It was the result of co-operative effort of efficient men working in harmony toward a common purpose, doing their best to serve their master and the general public.Footnote 65

A similar esprit de corps could be found in midlevel administrative spheres.Footnote 66 Clerical work at the Ford Motor Company was most conspicuous in two realms: A small group of accountants kept the books of the company and its subsidiaries, prepared tax returns, and served as a financial information clearing center for operations people.Footnote 67 A more substantial force of clerks was active in the logistical support of the factory; these unsung heroes of mass production staffed the sales, purchasing, specifications, traffic, receiving, and cost accounting departments.Footnote 68

In their recollections, these administrators uniformly recalled working within implicit hierarchies and informal protocols. “We operated without classifications and titles,” recalled one Ford accountant.Footnote 69 “There were no titles anywhere and no organization charts,” according to another former administrator.Footnote 70 The question of who reported to whom was “an intangible line. You couldn't see it on a chart anywhere,” said a third.Footnote 71 But despite the lack of charts, “the lines of authority were pretty clearly defined” and “we had pretty well defined departments.”Footnote 72

The complex paper trail required by factory logistics was strictly subordinated to the needs of the shop floor. While “it was generally understood” that record-keeping constituted “unnecessary overhead” if it “contributed nothing . . . but a lot of exchanging papers and figures,” the logistics departments developed their own records procedures within the bounds of this injunction.Footnote 73 Damon Yarnell describes well-oiled routines among the company's purchasing agents, who combined a sophisticated system of tracking stock and inventory with supple informal arrangements.Footnote 74 “We moved too fast to have any records catch up with us,” recalled one purchasing agent. “We used personal contact.”Footnote 75 As one Ford accountant summarized company culture: “Production was first, and book-keeping and accounting came second.”Footnote 76

Self-Mobilization and Cooperative Competition: Running the Shop Floor

Ford-style mass production is often seen as emerging from the same logic of management control as Taylorism. Accordingly, labor historians have tended to imagine the Highland Park shop floor as a thoroughly Taylorized operation, in which white-collar engineers, ensconced in a planning office, laid out the subdivision of tasks and dictated the pace of production.Footnote 77 The recollections of Ford's shop supervisors, however, tell a different tale. Running the shop floor was the responsibility of skilled mechanics and foremen not beholden to outside efficiency experts. Highland Park supervisors emerged from the shop and shared its culture; they rejected the theoretical distillation of “one best way” in favor of continuous improvements resulting from practice. From the superintendents down to the foremen, the skilled mechanics in charge of the shop floor harbored a pronounced ethos of initiative in working for the company. This was a “close-knit group of men who lived on the job,” as Sorensen noted in his memoirs. The accomplishment of meeting a punishing production schedule instilled a collective pride, “a sense of achievement by association.”Footnote 78

As in administration, there were no official titles; hierarchies and spheres of responsibility were implicitly understood.Footnote 79 A dozen “superintendents” had overall responsibility for production. These superintendents spent much of their time “roving”—that is, acting as “trouble shooters” in areas where machines had failed or shortages threatened to hold up the production flow.Footnote 80 Superintendents were men who had been with the company for many years and knew mass production intimately; their expertise was broad as well as deep, allowing them to move effortlessly between assembly, machining, and tooling and to coordinate the shop floor and the logistics departments. These superintendents “were strictly shop people. They were out in the shop; they loved the shop. They had no use for an office really.”Footnote 81

One of these superintendents was William Klann, who joined the Ford Motor Company in 1905 as a machinist and worked his way up the shop floor hierarchy. Klann recalled his role in these terms:

[In 1918,] I was made superintendent at Highland Park. Of course, that is what they called me. There was only one boss anyway and that was Henry Ford. We went to Sorensen and Martin for our orders and Mr. Avery and Hartner for our orders. You didn't have any title whatsoever. You just ran the shop, that's all. You ran that job and you had your own baby, like your chassis assembly was your job and the motor assembly was your job, and the transmission assembly was your job. Your job expanded, that's all. You kept going round. I took in the whole plant, actually. I watched the assembly and shipping.Footnote 82

Answering to the superintendents was a group of departmental production men, who were in charge of individual operations (the foundry, crankshaft production, assembly operations, etc.). It was the responsibility of these “general foremen” to make sure that their departments met the production goals. In doing so, they relied on their own respective foremen (who in turn directed the unskilled operatives). The foremen shared in the culture of independent initiative. “You didn't need instructions to increase the speed. You did that on your own,” recalled Roscoe Smith of his time as foreman in the generator department, where he was in charge of twelve operatives. “If you saw that you could make an improvement getting more pieces an hour, you went ahead and made the change.” It was only afterward that “you'd call the Time Study Department to change your time.”Footnote 83 Floor-level foremen “took pride in knowing that their costs were coming down.”Footnote 84

The company-wide injunction against red tape was reflected in a mechanism of real-time cost accounting that was supported by a well-defined but narrow paper trail. On the floor, costs were tracked exclusively in terms of time units or “minute costs”: How much time did it take to turn out a specific number of parts? This practice eliminated the need for dollar figures, which “the boys out in the shop didn't need,” and put responsibility for meeting production quotas firmly on the shop floor.Footnote 85 Clerks kept the books, but the logic of cost accounting was dictated by production routines, not by the office. As one of Ford's accountants described the process in 1926, real-time costing was

the only method through which Ford production costs are kept down to the minimum in the shop. They have no such elaborate device as a Planning Department, so-called, as you ordinarily run across in some text books. Every man is supposed to work for the interests of the company, and when he sees a leak in any place, he is supposed to stop it right away, and not wait . . . for some cost accountant clerk to come along 30 or 45 days later and say, Why, six weeks [ago] so and so happened. That is history then. By a time basis we are able today to know what happened in the department yesterday.Footnote 86

Or, as Klann recalled plainly, “On Tuesday if your cost was more than on Monday, you went out and found out why.”Footnote 87

Foremen and supervisors uniformly recalled that improvements in machining and assembly emerged from constant trial and error and the collective expertise of the shop. Foremen would come up with suggestions for how to improve a particular assembly operation; machinists would devise ways of repurposing tools that had become worn down. “I was experimenting all the time,” recalled Arthur Renner, general foreman in tools. “A lot of these ideas on mass production came from men like myself who were thinking on the job.”Footnote 88 Klann concurred: “The various departments would all cooperate in turning up new ideas. . . . A lot of these ideas came from the men as well as from people in supervisory positions. Lots of them came from the men.”Footnote 89

All told, Ford's shop supervisors—a group consisting of around forty superintendents and general foremen, along with several hundred line foremen—worked in a thick social dynamic characterized by both cooperation and competition. Noncodified hierarchies implied that it was impossible for anyone in a supervisory position to take his authority for granted; conversely, demonstrations of initiative, commitment, and skill promised social recognition and promotion. Collectively, superintendents and foremen operated under an implicit shop-wide system of peer oversight and evaluation. This dynamic appears to have unleashed considerable energies among skilled men who took great pride in and strongly identified with their work. Constant pressure to justify standing and authority with production performance and shop floor accomplishments created a high-strung atmosphere of commitment. This social dynamic underpinned the company's most prolific years, with Model T sales surging to over two million vehicles each year between 1923 and 1925.Footnote 90 “The period from 1919 through 1926 was the finest and most efficient organization they ever had,” recalled one of Highland Park's logistics clerks.Footnote 91

From the perspective of charismatic governance, it is noteworthy that this shop floor ethos prevailed without prodding by Henry Ford. Though Ford would frequently stop by the shop, make recommendations, or even lay hands on the machines, the supervisory group operated independently of these cameo appearances.Footnote 92 In his memoirs, Sorensen described Ford's leadership as “a radiant quality” that made “others spring joyfully into common action.”Footnote 93 This charismatic appeal appears to have been translated down to the shop floor through Ford's production staff. Steel specialist Alex Lumsden recalled this in striking terms:

These leaders [on the shop floor] were very great men. They may not have had a great deal of knowledge about what makes the solar system work, or the background of history, . . . but they had something which inspired you to do your best. It created a tremendous amount of loyalty of the part of a large, large group of men in the shop. One of the common remarks was, “Now listen, that's not the Ford spirit.” There was a Ford spirit. That was the common expression.Footnote 94

The esprit de corps among the supervisors should not convey the impression that the shop floor lacked stark hierarchies—quite the contrary. The term “Ford spirit” expressed the work ethic and status system of the skilled mechanics who ran the shop floor. It encompassed the foremen but excluded the unskilled “operatives” who manned the lines and worked the machines. The majority of these workers were recent immigrants, often of southern or eastern European origin and of Catholic faith. Because of these workers’ backgrounds, and relative lack of skill, their Protestant and northern European supervisors generally disqualified them from inclusion among their ranks—and from the social and professional recognition these supervisors accorded one another. In turn, the lower-skilled operatives had little reason to identify with their superiors or with the company they worked for. Monotonous tasks, punishing speeds, and limited chances for promotion, seniority, or employment security characterized unskilled work at Highland Park as much as elsewhere in the auto industry.Footnote 95

Line foremen had extensive powers over work discipline and used such powers in often arbitrary fashion.Footnote 96 According to Renner, superintendent Pete Martin “wouldn't tell [the foremen] what kind of policy to follow in dealing with our personnel. That was entirely up to you; that was your job. The main thing that Mr. Martin was interested in was making your standards and your production.”Footnote 97 Such discretion cut both ways. On the one hand, foremen recalled being responsive to their operatives’ needs: they would fill in while a worker hurried to the bathroom, let operatives switch positions to avoid exhaustion, or even allow them to abstain as long as the group had production covered.Footnote 98 On the other hand, such episodes of lenience could not counteract the fact that the “speedup” was intrinsic to the Ford production system. Superintendent Klann bluntly acknowledged this, saying of the operatives, “Of course, we were driving them in those days. There was no pace making. It was driving all the time. . . . Ford was one of the worse shops for driving the men.” Supervisors took advantage of the disciplinary power built into the mechanized assembly lines. “You wouldn't tell them to go faster. You would just turn up the speed of the conveyor.”Footnote 99

The charismatic dynamic among the supervisory staff, then, was a constitutive part of the harsh working conditions for which the Ford Motor Company became infamous. In 1914, Ford had tasked John R. Lee, a personnel manager with progressive leanings, with implementing the five-dollar day. Lee not only set up investigations into workers’ lives under the notorious “Sociological Department,” but also established an employment office that sought to formalize hiring and firing. Unskilled operatives resented the intrusions of the Sociological Department. The shop floor elite, however, were also skeptical of Lee's reforms, which they saw as meddling with the personnel prerogatives of plant foremen.Footnote 100 As part of the refashioning of his company after the buyout, Henry Ford dissolved the Sociological Department in 1921—a decision that returned authority over hiring and firing to foremen and superintendents. Those who had staffed the Sociological Department deplored the move as a turn away from enlightened labor policies.Footnote 101 According to Sorensen, however, the shop floor greeted the end of the Sociological Department with “a great sigh of relief.”Footnote 102

For the remainder of the interwar years, the Ford Motor Company resisted pressures from both unions and progressive-minded employment professionals to formalize labor relations. The implicit routines that shop supervisors experienced as a strength in production, the lower-skilled operatives experienced as arbitrary discretion. Unsurprisingly, the unionization drives of the 1930s demanded the protection of codified procedures. The skill-based collective ethos of Ford's shop floor elite, then, may help explain why the Rouge succumbed to the United Automobile Workers (UAW) only in 1941, later than the rest of the automobile industry.Footnote 103

Institutionalized Charisma: The Rouge

In their “Reminiscences,” Ford's staffers concurred that the pronounced esprit de corps that prevailed among them in the 1920s weakened in the 1930s. There were several reasons for this. One was the Depression, to which Ford's formula—“higher wages, higher production”—failed to provide an answer.Footnote 104 Similarly, Ford's increasing age and declining mental acuity damaged his credibility as a leader.Footnote 105 Unsure of his hold over the sprawling company, and unnerved by increasing militancy among the unskilled operatives, Ford retreated behind the one lieutenant he thoroughly trusted: the navy veteran and former pugilist Harry Bennett, whose connections to Detroit organized crime and control over plant security gave him considerable power at the Rouge.Footnote 106

Ford's backing of Bennett, who “wasn't considered a production man,” bewildered staffers, and they blamed much of the deterioration of the Ford ethos on his rise.Footnote 107 Tasked by Ford to keep labor in check, Bennett and his network of spies had full control over the employment office. From this key position, as chief engineer Sheldrick recalled, Bennett kept the entire organization in a “strangle-hold”: without Bennett's OK, “one could not hire, fire, raise or transfer a man.”Footnote 108 Foreman Roscoe Smith resented having to submit to Bennett's favoritism and hire “friends of his and friends of friends” who might turn out to be inept operatives.Footnote 109 The shop floor and low-level staffers “hated and feared” Bennett because he was seen to be interfering with production.Footnote 110 Klann, the Highland Park superintendent, actually left the company when operations moved to the Rouge, because there, “Bennett wanted to run the shop and we didn't work for Bennett; we worked for the Ford Motor Company.”Footnote 111 Liebold felt that Bennett's effect on the company was “disastrous.”Footnote 112 Though many wanted to believe that “Henry Ford didn't exactly understand the implications of all that Bennett did,” the strongman's rise at the Ford Motor Company appears to have irreparably damaged Henry Ford's standing among his staffers.Footnote 113 The “Reminiscences” convey the impression that those who carried the company in the 1920s saw Bennett's rise not as a continuation of the mission, but rather as its betrayal. Bennett, however, still had the founder's backing, so “the men didn't like it, but they had to tolerate it.”Footnote 114

The 1940s brought additional challenges. The UAW's success in organizing the Rouge upset shop floor dynamics. By establishing recourse procedures around Rouge workplaces in 1941, unionization severely constricted the authority of line foremen. Foremen, in turn, felt that Bennett's employment office went over their heads by negotiating with the lower-skilled operatives. They responded by forming their own union, the Foremen's Association of America (FAA). In dealing with the FAA, the company began deferring to War Production Board guidelines—adopting standardized procedures that clashed with the “unwritten rules” dictating Ford administration.Footnote 115

Given the severity of such conflicts, and considering how much Bennett's rise damaged Ford's credibility as a leader, it is striking that the administrative routines developed in the 1920s largely persisted. Slim accounting, implicit hierarchies, and noncodified spheres of competence endured throughout the 1930s.Footnote 116 Strict in-house recruiting and promotion remained an unquestioned principle, and the company remained closed to white-collar professionals.Footnote 117 Production supervision remained vested in a group of “roving” superintendents; engineering innovations continued to emerge from the shop floor.Footnote 118 Some persisted in their loyalty to Ford, even to heroic degrees. For example, W. C. Cowling was promoted to sales manager in the difficult period of the early 1930s, when dealers fiercely protested Henry Ford's insistence that company models retain a mechanical brake, which public opinion considered hopelessly outdated. Cowling, however, deferred to what he took to be Henry's superior technical judgment and traveled to dealers to plead for the Ford organization and its products. “I religiously tried to do it,” Cowling said.Footnote 119

In an even more remarkable pattern of collective initiative, staffers began, more or less openly, to circumvent the founder's directives when they considered them detrimental to the company. For example, in 1936, engineering moved the location of its workshop to escape Ford's constant “monkeying” with design details. Engineers would endeavor “to do things his way. But when it came to actually putting things into production we more or less took things in our own hands.” Henceforth, design changes bypassed the founder's input. Rather, they emerged from collective deliberations among midlevel staffers: “As far as the administrative organization of the Company was concerned, the advance model changes was a practical, personal arrangement between the chief engineer . . . , the head of tool design, and the production people. It was worked out on a ‘Let's talk it over’ basis.”Footnote 120 Similarly, after 1941, Sorensen and Edsel Ford essentially sidelined Henry from the conversion to war production, because, as Liebold recalled, Henry “was no longer able to keep up” with the developments.Footnote 121

In the 1930s, then, the inspiration for the company's noncodified routines began to depend less and less on Henry Ford and became increasingly attached to the organization itself. Charisma became less personal and more institutionalized.Footnote 122 As Ford's authority declined, his staffers continued to run the company according to the principles initially inspired by the founder's mission, even if that now required circumventing his directives, excluding him from deliberations, or acting against his wishes outright. “There wasn't the same leadership that we had before,” Ford's chief accountant recalled, but “of course, the work was cared for.”Footnote 123

The recollections of staffers thus contradict the idea that the Ford Motor Company descended into managerial chaos after the 1919 buyout. The reality is rather more complex. During the 1920s, the company operated on a remarkably effective “charismatic” administrative pattern inspired by Henry Ford's producerist mission. Ford arrogated the last veto on all strategic matters and exercised it frequently. For the day-to-day realities of administration, however, the collective discretion, judgment, and initiative of his staffers was decisive. Ford's staffers did assert a crisis in leadership during the 1930s. However, so ingrained were routines of administrative self-initiative that when Ford's leadership inputs became counterproductive or ceased entirely, the company was largely able to continue operating without them.

Conclusion

To business historians working in the classical vein, Weber's ideal type of rationalized bureaucracy served as the theoretical anchor for understanding the structure of the modern corporation.Footnote 124 In this view, the modern corporation, with its ostensibly stable and efficient administration, necessarily stood in antithesis to charismatic rule, with its rebellious orientation and seemingly amorphous organizational character. This exclusive focus on rational administration, however, implied a rather selective reading of Weber, whose analysis proceeded from the premise that all types of “legitimate rule” require socially constituted mechanisms of organization. As Weber insinuated, and as the example of the Ford Motor Company demonstrates, charismatic authority does not imply organizational anarchy. Rather, it may give rise to a specific type of organizational governance, one that exhibits its own peculiar methods of mobilizing subordinates, delegating authority, and coordinating an effective division of labor.

This finding may be of use to business historians on at least two levels. First, it contributes to ongoing efforts to understand the organizational mechanisms that make firms run: how they “learn by doing,” how they develop routines, how they coordinate tasks and process information.Footnote 125 In particular, the notion of charismatic governance suggests a systematic vocabulary for describing certain social-informal features that standard concepts of organizational theory struggle to capture. As sociologists have long argued, organizational practices always rely on informal procedures and personal networks to function effectively, and they always require consent among subordinates.Footnote 126 Charisma, understood as “mobilizational” governance, expands on these insights. Central aspects of charismatic governance discussed above—the notions of self-mobilization, esprit de corps, cooperative competition, and noncodified routines—highlight the intrinsically social nature of what goes on inside the firm.

Second, the notion of charismatic governance may be helpful for those business historians who grapple with the challenge of thinking beyond the parameters of the profitmaking firm.Footnote 127 The example of the Ford Motor Company demonstrates the misunderstandings that can arise when historians assume that businesses reside in a sealed habitat of pure economic rationality. It is possible that organizations that pursue aims beyond profit, or that harbor an explicit agenda of social and political transformation, more easily develop features of charismatic governance (of course, Apple under Steve Jobs or Tesla under Elon Musk come to mind). The lens of charisma allows business historians to see such an agenda in a different light: not as window dressing, not as an aberration from theoretical assumptions, but as reflecting political commitments that have organizational consequences.