I needed to see it written in black and white, up on a wall.

جہاں کوئی اپنا دفن نہ ہوا ہو وہ جگہ اپنی نہیں ہوا کرتی

Jahan koyi apna dafn na hua ho woh jagah apni nahin hua karti

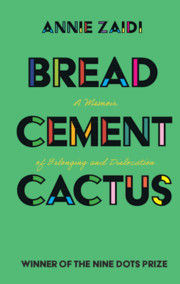

Travelling from Spanish to English to Urdu with its curlicue graces, that line waited to trip me up in my own language. I found it at a stall selling posters at a literary festival. It’s from Gabriel Garcia Marquez’ One Hundred Years of Solitude: A person does not belong to a place until someone beloved is buried there.

In north India, where my family is from, a corpse is sometimes referred to as mitti. Soil. Earth, if you prefer, and when you want to emphasise your relationship with the land, you might declare, ‘Yahaan meri purkhon ki naal garhi hai’, ‘This is where my ancestor’s umbilical cord is buried’.

I must have come upon this sentence about burying be-loveds when I first read Marquez, but it hadn’t leapt off the page then. I hadn’t buried anyone yet. I hadn’t even been inside a graveyard. I hadn’t yet been told that I didn’t belong in my own country, or that I had a smaller right to it. Belonging, however, had always been a fraught question for me. Friends from journalism school continue to tease me about the first day of class when a professor asked us to introduce ourselves: just names and where we’re from. I said I wasn’t sure where I was from, and then proceeded to list everywhere I’d lived thus far.

What I was trying to say was that I felt dislocated, and anxious about my fractured identity. I was born in a hospital and I don’t know if my cord was buried at all. I’d never lived in the city of my birth and only briefly in the city where my grandparents lived. Leaving us with her parents while she went back to university, my mother quit a bad marriage. Later, she found a job and moved with her two children to a remote industrial township in Rajasthan. The need for bread, and milk for the children, overrode her unease at being so far from everything familiar.

We rarely had much choice about moving. Four walls and a roof don’t do much good if there’s no bread on the table. So we moved. Thoughts about how we felt about where we lived were an indulgence we couldn’t afford.

Now here I was, staring at funky literary memorabilia, thinking about what I’d do with myself when I was my mother’s age.

I bought that Marquez poster and took it to the framer’s. For a moment, I stood hesitating. Framing would prolong the paper’s life. On the other hand, a glass and wood frame might be damaged in transit. Transit, at any rate, was inevitable.

JK Puram is an industrial township in Rajasthan, flanked by the Aravalli hills and a cement factory.