In the later eighteenth century, John Wesley's Methodist Connexion experienced periodic but sudden outbreaks of religious fervour, leading to ‘multiplied conversions’:Footnote 1 what were termed local revivals. Typically, these were spontaneous rather than planned; were led by lay members, often women; involved child conversions; and emphasized the ministry of prayer rather than preaching. As Henry Rack observes, however: ‘By the 1830s the professionals had moved in with prescriptions and special techniques which guaranteed a revival if they were followed.’Footnote 2

Other students of revival such as John Kent, David Bebbington and Michael McClymond have also perceived this trend.Footnote 3 From its inception as part of the mid-eighteenth-century Evangelical Revival,Footnote 4 Wesley's mission had been characterized by what David Hempton has called ‘the interior dialectic of Methodist experience – its combination of spiritual freedom and order’.Footnote 5 Over time, however, the ‘institutional’ dimension had grown more powerful than the ‘inspirational’ one, and ‘Methodism was transformed from a renewal movement within Anglicanism into an autonomous organized church.’Footnote 6 This article explores this transition through reviewing the debate around 1800 about whether and how continuing outbreaks of local revival could find their place within this new church.

The Challenge of Local Revivals

For Wesley and many of his Anglican colleagues, while the Spirit worked quietly and routinely through grace in the daily lives of believers, the era of widespread extraordinary action had ended with the primitive church; Wesley argued that once Christianity had become the state religion, under the emperor Constantine, such events ceased ‘because the Christians were turned heathens again, and had only a dead form left’.Footnote 7 However, he sometimes portrayed Methodism as the rekindling of the flame of Pentecost, and did not exclude the possibility that the Spirit was again at work in an extraordinary way.Footnote 8 In practice, after the excitement of the 1730s and 1740s had subsided, smaller-scale revivals continued to occur periodically within the Connexion, in a wide range of localities. Indeed, as Wesley had predicted, there was an ‘almost rhythmic pattern of generational revivalism’.Footnote 9 In Cornwall, local revivals were reported broadly once in every sixteen years.Footnote 10 Wesley's preachers eagerly shared news about revivals with him and with each other. In 1754 the Scottish minister John Gillies published his exhaustive collection of narratives of the Evangelical Revival, for which Wesley acted as marketing agent in England.Footnote 11 By 1800, twenty articles on revivals within Wesley's Connexion had appeared in its journal, the Arminian Magazine, often contemporary accounts. Among them were reports on revivals across the British Isles, including Yorkshire (1747–8, 1778–9, 1782–3, 1792, 1794), Cornwall (1781–2), Norfolk (1781–2), northern Ireland (1767) and Cork (1782).

Some revivals arose in response to preaching, for example by the Irish Wesleyan John Smith (1713–74). In 1767 he wrote of widespread revival in northern Ireland, which he linked to his own preaching visits.Footnote 12 John Valton (1740–94) sent Wesley a stream of reports of revivals in response to his preaching, as at Bath in 1782,Footnote 13 and Batley, Yorkshire, in 1783.Footnote 14 Other preacher-led revivals included those in Manchester (1783) and Kent (1784).Footnote 15 In the 1790s, preachers such as Mary Barritt (1772–1851) and William Bramwell (1759–1818) enjoyed sustained success in encouraging a series of local revivals in northern England;Footnote 16 in Yorkshire alone, membership rose by 59 per cent between 1790 and 1797 in what has been called the Great Yorkshire Revival.Footnote 17 Women evangelists were often prominent; indeed they dominated this revival.Footnote 18

What excited contemporary Methodists most, however, was when the Holy Spirit seemed to work directly through the Methodist people, women and men, children and adults, or even drew on non-connexional agents. In 1796 the preacher Thomas Taylor (1738–1816) analysed the origins of the 1778–9 revival in Birstal:

The preaching of the word was attended with much energy and life … But our Lord did not confine himself to preaching alone; he let us see that he could carry on his own work without us: Prayer-meetings were singularly useful … But in short, dreams and visions, thunder and lightning; yea, the very chirping of a bird was made successful to the awakening sinners.Footnote 19

Some local revivals drew on extraordinary manifestations of the divine, although the preachers always viewed these with caution. Visions by young girls were a major feature of a revival on the Isle of Man in the late 1770s, but the preacher Thomas Wride (1733–1807) complained, in reporting to Wesley, that he could ‘never get regular information’ since they prophesied in Manx.Footnote 20 And as revival spread across Yorkshire in the mid-1790s, a central role was played by the mystic Ann Cutler, known as ‘Praying Nanny’, who claimed to be in union with the Holy Trinity, a claim which Wesley acknowledged, but suggested she keep to herself.Footnote 21

Whilst welcome in many ways as evidence of God's continuing support for Wesley's mission, local revivals were also hugely problematic for the leadership, in four related ways. Firstly, by definition they went beyond the scope of existing national and local plans, and were therefore potentially destabilizing. Of course, Methodists often longed for revival. The 1762 Dales revival was preceded by months of fasting and prayer each Friday;Footnote 22 and in early 1782 John Valton told John Wesley that his Manchester members were fasting in the hope of revival.Footnote 23 However, revivals typically involved short-term and frequently large-scale increases in attendance at chapels and other meetings, and the local Methodist infrastructure sometimes struggled to cope. During the mid-1780s revival at St Austell, the preacher Adam Clarke (c.1762–1832) reported that on one occasion ‘Our chapel, though the largest in the circuit, is so filled, that the people are obliged to stand on the seats to make room … Last Sunday night I preached there, and was obliged to get in at the window in order to get to the pulpit.’Footnote 24 Even worse, mass conversions often failed to yield long-term increases in membership. As the leading preacher Alexander Mather (1733–1800) told a colleague in 1796, spiritual after-care was essential to forestall such attrition:

[You must] 1. … see that they meet with some leader who is a real friend to the Work. 2. You must carefully watch the time when there is a decrease of that exceeding great joy which they first experienced … 3. Prevail upon them likewise to meet in band with one who will prove a nursing father or mother to them.Footnote 25

Secondly, local revivals disturbed the existing connexional order in other ways. In the early stages, confusion was often rife; when revival came to Weardale in 1771, one local leader reported: ‘We met again at two, and abundance of people, came together from various parts, being alarmed by some confused reports’.Footnote 26 Across Yorkshire in 1794, Mather found that ‘[t]here no doubt is, & in the nature of things must be a noise & some degree of confusion.’Footnote 27 The rhythm of regular worship and corporate activity was interrupted. Mather suspended weekday preaching in Hull, explaining: ‘I have lately adapted to prayer meetings with short exhortations, instead of preaching, wishing to work with God.’Footnote 28

Even where the Holy Spirit seemed to be working within the connexional framework, Methodist preachers, leaders and members could feel threatened. In the early 1760s Mather had encountered opposition from ‘some of the old Methodists’ when using prayer meetings as a tool for evangelism in Staffordshire, possibly because his wife led some of them; malicious stories circulated ‘either against the work, or the instruments employed therein, my Wife in particular; whom indeed God had been pleased to make eminently useful’.Footnote 29 As Bramwell observed frankly of Cutler's missionary activities in 1790s Yorkshire:

Wherever she went there was an amazing power of God attending her prayers. This was a very great trial to many of us: to see the Lord make use of such simple means, and our usefulness comparatively but small. I used every means, in private, to prevent prejudice in the societies; but with many of my good elder brethren it was impracticable.Footnote 30

Thirdly, the extravagant expressions of fervour which characterized revival meetings troubled many, both within and outside Methodism, because of their perceived lack of ‘decorum’.Footnote 31 Such concerns were of long standing. In his highly influential account of the 1730s New England revival, the Congregationalist preacher Jonathan Edwards (1703–58) had noted that ‘it is a stumbling to some, that religious affections should be so violent (as they express it) in some persons’.Footnote 32 Accusations of fanaticism had dogged Methodists. In 1764 one Welsh minister had ridiculed their ‘wild Pranks … singing, capering, bawling, fainting, thumping and a Variety of other Exercises’.Footnote 33 At the Methodist Preachers’ Conference in 1796, Bramwell led prayers at a love-feast in spectacular fashion. One description echoed the account in Acts 2 of the day of Pentecost:

Bro. Bramwell went to prayer, & the power of God fell like lightning for quickness & like the rushing wind for effect. Many of the people in the gallery seemed to fall upon the floor & others was [sic] so frightened by the noise that they got up from their places & ran downstairs & out of the doors without looking behind them.Footnote 34

For the Yorkshire clergyman Joseph Nelson, however, such comparisons were outrageous. For him, the operations of the Holy Spirit had been almost entirely institutionalized, leaving the Bible, as interpreted by clergy who had been well educated, as the only sure guide.Footnote 35

Fourthly, however, there was a more fundamental issue. In encouraging local revivals, Wesley and his colleagues were taking significant risks. His itinerant preachers were carefully selected, trained (through a combination of on-the-job training and planned reading) and supervised, and were subject to annual performance appraisal. Through imposition of the Connexion's Model Deed, Methodist chapels were open only to preachers following approved doctrine; and within their walls only approved hymns could be sung.Footnote 36 Yet in many cases, local societies were now falling under the sway of revivals led by lay members of all ages, and focusing on unscripted, extempore prayer sessions, often held in private homes.

In thus casting themselves adrift from the connexional anchor, how could Methodists be sure that what they were experiencing was the work of the Holy Spirit and not of the devil? In Norfolk in 1782, the preacher James Wood (1751–1840) recorded his concerns over some apparent converts, ‘whose experience, I strongly suspect; not from their fainting, fits &c. but from an inability to give any clear, rational account of their conviction or conversion’.Footnote 37 Joseph Entwisle (1767–1841) responded similarly to an ecstatic meeting at Bell Isle in Yorkshire in 1794: ‘All was confusion and uproar. I was struck with amazement and consternation … What shall I say to these things? I believe God is working very powerfully on the minds of many; but I think Satan, or, at least, the animal nature has a great hand in all this.’Footnote 38

The Publication of A Selection of Letters

At the end of the eighteenth century, interest in local Methodist revivals, both within the Connexion and beyond, was particularly intense, for three related reasons. First, criticisms of popular demonstrations of religious faith were especially strident during times of economic hardship and of social and political stress. In 1790s Britain, fears of French-inspired unrest led to government repression,Footnote 39 and to widespread tensions between supporters of ‘Church and King’ and those seen as outsiders, which could well include Methodists.Footnote 40 This worked both ways. In December 1792, Entwisle feared for his family as rioters paraded around Leeds, praying: ‘O Lord, hide me, my dear wife, all my friends, and thy dear people in the secret of thy pavilion till every calamity of life be overpast.’Footnote 41

For Wesley and his contemporaries, religious and political order were inseparable; Joseph Nelson was lauded in his obituary as ‘a firm and zealous supporter of the Protestant Religion, and the British Constitution, as by Law established, in Church and State’.Footnote 42 Popular movements were often tainted by association with the excesses of the French Revolution, and Methodists understood these risks. One leading preacher wrote in 1794: ‘I would recommend all our Societies at this time, to be much in prayer; the state of the nation & the state of the Church (I mean the Church of Christ) demands it. It is surely an awful time, & such as calls aloud for humiliation.’Footnote 43 Mather took action in Sheffield in 1797 on finding that a Methodist-funded teacher ‘had become a strong republican in civil & religious things’,Footnote 44 while Entwisle recognized that lay Methodists were sometimes over-enthusiastic in revival work: ‘Many who are exceedingly active in this way are truly pious: if their zeal and fervour were under the direction of wisdom and prudence, they might be very useful.’Footnote 45

Second, Wesley's movement was experiencing sustained and wide-ranging tensions as it struggled to find a new way to define and govern itself following the death of its ever-dominant founder in 1791,Footnote 46 which led to the mass secession of Alexander Kilham's Methodist New Connexion in 1797.Footnote 47 There were numerous linked power struggles: between local societies and the connexional centre, between Wesley's surviving itinerants and a new generation of preachers, between chapel trustees and society leaders, and between champions of what was often seen as lay democracy as distinct from clerical oligarchy. For the leading Bristol Methodist layman William Pine, disorder in the Connexion and in chapel revival meetings were two sides of the same coin. He told one preacher in 1796: ‘The Spirit of Disloyalty and Innovation go Hand in Hand, and will most certainly spread if it be not firmly opposed by those who have Piety and Respectability in the Connection … Decency and Decorum should be preserved in all Places of public Worship, for God is not the Author of Confusion.’Footnote 48

Third, however, some Methodists hoped that the Great Yorkshire Revival might presage another national ‘Great Awakening’, if not the Second Coming of Jesus Christ. John Moon (1751–1801) wrote excitedly from Sheffield that the phenomenon ‘must surely be a prelude to that glorious conquest of Grace, which we are prophetically assured, shall take place in the last days; and hence, is eminently preparing the way for the grand Millennial Reign of our Redeeming God’.Footnote 49

This tension between fear of disorder and expectation of a new order runs throughout A Selection of Letters, &c., upon the late Extraordinary Revival of the Work of God. The publisher was William Shelmerdine, who was based in Manchester.Footnote 50 He clearly had some links with Methodism and wider Evangelical religion, having published a collection of pastoral letters by the Evangelical clergyman William Romaine (1714–95) in 1798Footnote 51 and a work by the Methodist writer Joseph Nightingale (1775–1824) in 1799,Footnote 52 while subscribers to his collection of improving verse included the leading Wesleyan Thomas Coke (1747–1814).Footnote 53 The firm had a varied portfolio: it published Robinson Crusoe (which also had moral and religious content) around 1800, and various tradesmen's practical guides, but it was probably best known for its broadsheet ballads and cheap editions of short stories: the Bodleian Library collection of broadside ballads has some thirty items with a Shelmerdine imprint between 1800 and 1849.Footnote 54

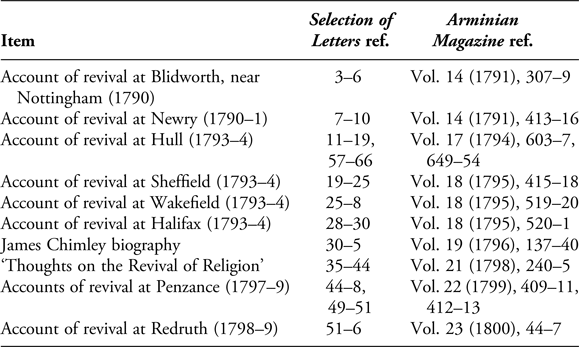

Most of the slim volume of sixty-six pages comprised accounts of eight recent local revivals; there was also a brief spiritual biography of James Chimley, who had been converted before dying in 1795, in his fourteenth year; and a ten-page essay entitled Thoughts on the Revival of Religion in the Prayer-Meetings by an anonymous ‘Well-Wisher to Zion’. All the material had already appeared in the Arminian Magazine, and (apart from the report on Hull) the sequence was unchanged.

Table 1. Sources of material in Anon., A Selection of Letters

At this period the Methodist Magazine (as the Arminian Magazine was titled from 1798) had a print run of many thousands, so these accounts were already familiar to many Methodists.Footnote 55 There is every reason to think that Shelmerdine intended the publication to be helpful to Methodism; perhaps it arose from discussions at or around the Preachers’ Conference of 1799, held in Manchester. The layout of the pamphlet (including its lack of a contents page, preface or introduction, or index) suggests that it was produced at pace; but what precisely was its purpose?

A clue can be found in the choice of material. The Selection of Letters drew from Magazines between June 1791 and January 1800, but accounts of seven other revivals published during this period were excluded. Most of these related to events which were relatively distant in time (such as the 1778–9 Birstal revival in Yorkshire) or place (for example, the 1797–8 revival in St Bartholomew, West Indies). But the omission of the report by Zechariah Yewdall (1751–1830) on the revival at Otley, Yorkshire, in 1792–3 is surprising. It seems to reflect the unorthodox, indeed unique, origins of that revival. In 1792 Elizabeth Dickerson, aged around nineteen, with no Methodist connections, began itinerating north of Leeds, following two ecstatic trances in which she had visions of heaven and hell. Thousands heard her speak, sometimes also hearing ‘the sweetest music’, and while two of Wesley's preachers, Yewdall and Thomas Dixon (1745–1820), both recorded doubts about her authenticity, they accepted that revival followed shortly afterwards.Footnote 56 So in essence the Selection of Letters was addressing the questions: what was going on in Yorkshire and elsewhere? Was it truly the work of the Holy Spirit? If so, could it be replicated?

The narrative accounts were clearly intended as exemplary; indeed they shared many common features and used consistent terminology.Footnote 57 They explored six key themes. First, and in striking contrast to events at Otley, these local revivals were all presented as led by Wesleyan preachers. At Blidworth, revival followed prayer meetings held after preaching services in the chapel, and was sustained through the efforts of both (full-time) itinerant and (part-time, volunteer) local preachers;Footnote 58 and the reports on events at Newry, Hull and Halifax were equally explicit that itinerant preachers had initiated and then presided over the revival.Footnote 59 At Redruth, the spark of revival was lit at a service conducted by John Hodgson, an itinerant preacher.Footnote 60

Second, and again unlike the Otley case, these revivals were portrayed as developing from within the ecclesiastical structures of mainstream Wesleyan Methodism. Some accounts emphasize the importance of Quarterly Meetings in spreading revival. On such occasions, a circuit's preachers and lay officials would come together to review its spiritual and financial health, plan preaching for the coming quarter and enjoy Christian fellowship. At Sheffield and Wakefield, revival began during the Quarterly Meeting; at St Ives, that was when it was at its height.Footnote 61 Other revivals were linked to highlights of the church year: in Penzance it was ‘at our Love feast, on the Christmas quarter-day, the Lord began to breathe on the dry bones’;Footnote 62 at Redruth the first stirrings came during the New Year's Eve service, and were echoed a week later at the annual Covenant Service (with which Methodists mark the new year) at Truro.Footnote 63 At Riverbridge, near Hull, revival burst out on Easter Sunday.Footnote 64

A third feature shared by all these accounts was the central importance accorded to prayer meetings in generating and maintaining the momentum of the Holy Spirit's work. At Newry, for example, such meetings were held after the preaching services, and often lasted four hours.Footnote 65 Frequent, often lengthy and large-scale, prayer meetings were a core feature of revival in every area.Footnote 66 Chimley himself had been converted at one such meeting.Footnote 67 As Mather told the prominent Methodist layman William Marriott (1753–1815) in 1794, as revival spread across Yorkshire: ‘The means it pleases God to own most are prayer meetings. These continue from 7 to 9, 10, 12 o'clock at night, yea till 2, 4 & 6 in the morning. In some of them 5, 7, 12, 20 & at one time more than 30 have professed to be awakened & converted.’Footnote 68

Fourthly, as so often in Methodist revivals, these reports revealed the prominent role played by children and young people as active participants in, and exemplars of, the work of grace. Chimley's biography of course highlighted this phenomenon, and asserted that ‘[t]he holy life, and happy death of James Chimley is one proof’ that these revivals were ‘a blessed and glorious work of God’, albeit ‘attended with some irregularity’.Footnote 69 Many of the accounts describe significant numbers of conversions amongst the young. At Blidworth, a fifteen-year-old was an early convert;Footnote 70 at Sheffield, Moon recorded, ‘[i]t was marvellous to behold boys and girls of ten or twelve years of age, so violently agitated, and so earnestly engaged to obtain mercy … Even little boys and girls now have prayer-meetings among themselves’.Footnote 71 From Riverbridge, Hull, Mather offered a detailed report of his successful struggle to save a group of young men from the evils of football.Footnote 72 Nearby, two boys aged eight and twelve were converted: ‘Next day they each of them wrote a letter to their relations, describing the work which the Lord had wrought upon their souls, and the consolations they experienced, interspersed with pertinent remarks and observations, that would not have discredited persons who have been long acquainted with the things of God.’Footnote 73 There were also striking events at Redruth, where one father brought two small children into the pulpit to testify to their conversion, ‘and tho’ they could scarcely be seen, they lifted up their hands to heaven, and with tears of humble praise, calmly told the congregation what the Lord had done for their souls’.Footnote 74

Fifth, these published accounts emphasized the transformative impact of revival. Quantitatively, the numbers of conversions were impressive: at Hull, Mather reported adding ‘upwards of one hundred and fifty’ members in a week in April 1794, with conversions averaging twenty to thirty at each meeting;Footnote 75 while a report from Redruth claimed in June 1799 that more than two and a half thousand new members had been recruited since Christmas.Footnote 76 The accounts also emphasized the immediate and positive impact of revival on the daily lives of new converts. Chimley was one exemplar; Charles Atmore (1759–1826) was convinced that the Holy Spirit was active amongst the people of Halifax in 1793–4 because ‘[s]ome have now evidenced the reality of the change upon their hearts, for twelve months, by a holy life.’Footnote 77 Similarly, Mather reported that across Yorkshire new converts ‘shew it to be real work by their lives & conversations’.Footnote 78

One final theme runs through all these reports, and that is the authors’ concern to address the charge that such revivals generated ‘confusion’ or ‘wildness’. The picture set out in the Selection of Letters was nuanced. The authors accepted that the ‘cries of the distressed’ during revival meetings could be noisy and disturbing. But the evidence was clear that the Holy Spirit was at work. In Hull, ‘[t]here were [sic] nothing irrational or unscriptural in these meetings’, wrote Mather; while Moon reported from Sheffield that ‘[i]t could not but appear to an idle spectator, all confusion, but to those who were engaged therein, it was a glorious regularity.’Footnote 79 Linked with this was an attempt to overcome the class prejudice sometimes found amongst leading Methodists; Wesley's close associate Elizabeth Ritchie had been contemptuous on this score of the Sheffield revival.Footnote 80 However, Owen Davies claimed that the Penzance revival was the height of respectability: ‘I was called upon some time past to pray with a gentleman, an officer in the army, and other respectable men, together with some of the most dressy women of the place.’Footnote 81

That said, this was clearly not connexional ‘business as usual’; at one Cornish service, Hodgson found it impossible to deliver a sermon because of the noise, while at a Sheffield love-feast, the ‘customary collection for the poor’ was disrupted.Footnote 82 It was a challenge for the preachers: during the Yorkshire revivals of the 1790s, Mather feared initially that they would be inhibited by ‘a too anxious attachment to decorum and order’; but in due course even he felt obliged to introduce ‘some regulations, in the most gentle way’ to manage the lengthy prayer meetings being held locally, after reports that they were ‘offensive to the magistrates’.Footnote 83 Large-scale meetings of men and women, with no set procedure and probably no clergy or gentry present, held at night and behind closed doors, were of obvious concern to the authorities.

Of course, there had never been a simple binary choice between ‘inspiration’ and ‘institution’. Even the mystic Cutler worked alongside Wesley's preachers within the circuit system, and her mentor Bramwell was not only a passionate prayer leader but adopted a systematic approach to evangelism. While clearly inspirational, he did not act alone, but ‘employed the talents of the local preachers, leaders, and other individuals, in prayer’;Footnote 84 his techniques included 5 a.m. prayer meetings, intensive house-to-house visiting and pastoral care for new converts, comprising one-on-one advice sessions and supervised reading programmes.Footnote 85

Managing Revival: A Code of Good Practice

The essay on good practice, Thoughts on the Revival of Religion in the Prayer-Meetings,Footnote 86 set out a clear strategy for generating and sustaining local revivals. It was to maintain the systematic organization developed by Bramwell and others, to reassert connexional control, to reduce dependence on charismatic individuals (whether prophets or preachers) and to lower the emotional temperature. First it compared recent events with the London ‘revival’ of 1761. This had been led by the maverick millenarian Methodist preacher George Bell (d. 1807) and driven by his personal revelation through dreams and visions, but collapsed in ridicule and embarrassment. In contrast, the essay adopted a primarily institutional perspective, although its author, in proposing detailed ‘regulations’ for the management of revivals, added: ‘Sometimes when the power of God is uncommonly present in a meeting, attending too minutely to any particular plan, might do much harm: God alone can direct at such blessed seasons.’Footnote 87

The essay argued that the work of God was best advanced through a local team effort, managed by trained and experienced preachers, supported by active members of local Methodist societies, and grounded firmly in the connexional mainstream: ‘The case at present is widely different [from that of George Bell]; the active persons in the Prayer-Meetings, in general, are remarkable for an affectionate attachment to their preachers, they constantly attend all the means of grace: they ardently love their Bibles; and they steadily adhere to the Methodist doctrines and discipline.’Footnote 88

Once it had been ascertained that the Holy Spirit was at work, the Methodist society should establish a cadre of members under the guidance of a full-time preacher, to manage the anticipated upsurge in interest. They should organize a series of prayer meetings, and deliberately use a variety of prayer leaders: ‘Our friends who preside in the Prayer-meetings, ought to be exceeding careful that those who exercise in prayer, are exemplary in their lives and conduct … It is likewise necessary … to take care not to depend too much on any particular persons … lest our dependance [sic] be more in man than in God.’Footnote 89

A detailed format for such meetings was suggested. Though revival meetings often attracted public interest, entry to chapels was to be strictly controlled. In Newry in 1790, for example, ‘[m]any of the careless and profane gathered about the house, but were not admitted’.Footnote 90 Teams of prayer leaders, counsellors and administrative support staff were to be deployed, under the management of a preacher or senior member. The meeting's president was to supervise a programme of ‘short and lively’ prayers, interspersed with hymns.Footnote 91

If individuals showed signs of experiencing the pain of awareness of their sins or the joy of salvation, they were assigned a counsellor to encourage and support them; apparent manifestations of God's grace might in fact be due to sickness or fantasy, or even demonic in origin. But when these personal crises ended in conversion, the counsellor would brief the president, who would inform the congregation and lead general thanksgiving. Meanwhile an administrator would record the convert's contact details, and assign them to a class in the local society. This was accepted good practice; Bramwell followed it, as did Entwisle during the Leeds revival of 1794: ‘I proposed to the young converts, who wished for it, that they should give in their names, and our friends would meet them once a week in little companies … One hundred and twenty persons gave in their names.’Footnote 92

Finally, a calm and orderly atmosphere should prevail as far as possible, and when the meeting ended the participants should disperse immediately, without annoying the neighbours: ‘Much good has been lost, and much evil arisen, from several persons collecting together at the door, or in the street, and in a trifling manner conversing about what has been done.’Footnote 93

In short, whilst celebrating evidence that the Holy Spirit was so obviously at work, and offering practical suggestions on how such success could be replicated, both the essay on good practice and the accompanying accounts of local events stressed the measures needed to keep revivals under moral and political control. If one purpose was to attract new members, including their weekly penny subscriptions, it was vital also not to scare the authorities, nor indeed the respectable middle-class supporters of Methodism, whose large but discretionary financial contributions were increasingly important.Footnote 94

The managerial approach set out in Thoughts on the Revival of Religion in the Prayer-Meetings was however not only about organizational survival and development, nor was it just a response to external and internal pressures. It reflected core Wesleyan theological positions. One, as we have seen, was the firm view that both God and Satan were active in contemporary Britain, and that distinguishing between their work was a significant challenge requiring both discipline and discernment. Another was that sinners were called not only to a momentary act of repentance but to a life of sacrificial love for God and humankind. Yet another was the Wesleyan morphology of spiritual development, in which the sinner was first ‘awakened’ or ‘convicted’ of sin, next ‘converted’ or ‘justified’, and then (at least as an aspiration) achieved ‘sanctification’ or ‘perfection’, complete release from the power of sin. The phase of ‘conviction’ prior to ‘conversion’ was traumatic, especially if prolonged;Footnote 95 while ‘sanctification’ was often found only at the end of life, if at all. Furthermore, individual spiritual development might be nonlinear: there could be troughs as well as peaks. As Rack and Bebbington note, conversion was therefore only one of many possible positive results of the Spirit's work.Footnote 96

John Allen (1737–1810) observed during the Manchester revival of 1783: ‘We have still hardly a meeting but one or another finds peace with God, or has his backslidings healed, or else is renewed in love.’Footnote 97 During the Great Yorkshire Revival, Mather also reported varying outcomes: ‘Many are awakened, converted, & profess to be sanctified … In some of the above circuits there is a very agreeable recovery amongst many of the old members.’Footnote 98 Throughout this hazardous journey, the sinner needed emotional, spiritual and practical support, and that required human, physical and indeed financial resources to be marshalled and deployed. As Fredrick Dreyer has noted, Wesley's Methodism was ‘[a] mixed association whose ranks included members in all states of spiritual development’.Footnote 99

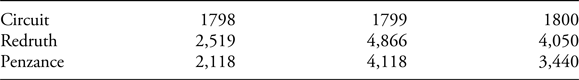

There was also a theological perspective on the fluctuations in membership often seen in revivals. The 1800 Conference took place against the immediate background of revival in Cornwall, where some of the inflow of recruits proved temporary.

Table 2. Membership in selected Cornish circuits, 1798–1800

Sources: Minutes of the Methodist Conferences, vol. I (London, 1862), 424; Minutes of the Methodist Conferences, vol. II (London, 1813), 16, 54.Footnote 100

The essay on good practice offered an explanation: as news of revivals spread beyond local Methodist societies, it drew in the unchurched, whose immediate emotional response was not grounded in any spiritual preparation and might therefore not last.Footnote 101 As John Pawson commented in 1796: ‘After any extraordinary revival of the work of God in any place there has been what has been frequently called a sifting time, and the gold has been separated from the dross and there has been a falling away.’Footnote 102

Conclusion

The Selection of Letters documents what Rack has called ‘a transitional phase from the old spontaneous revivalism to the planned revivalism of the nineteenth century’.Footnote 103 From its inception, Wesley's movement had sought to respond to the promptings of the Holy Spirit within the context of limited organizational capacity and wariness of over-enthusiasm. In Mack's phrase, it always exhibited a ‘creative tension between spirit and discipline, creativity and regulation, expansion and consolidation’;Footnote 104 for Hempton, ‘revivalism and connectional managerialism were always unhappy bedfellows’.Footnote 105 In many ways it struck an effective balance: between 1770 and 1810, membership in the British Isles (as published in the annual Conference Minutes) more than quadrupled, from some 30,000 in 1770 to approaching 140,000 in 1810. Indeed, for the next century, the Connexion continued both to grow in membership and to avoid financial disaster.Footnote 106 The growth trajectory was far from smooth, however.

In the later 1700s, many Methodists eagerly devoured a succession of exciting reports of local revival, including the Spirit-led work of teenage boys and the prophetic witness of teenage girls and women, looking towards nationwide revival or even the Second Coming. Meanwhile, within the Connexion and beyond, there was growing concern at this apparent breakdown of ecclesiological, social and potentially political order, and a new generation of preachers, exemplified by Clarke, was delivering the gospel through reasoned argument and biblical exegesis.Footnote 107 By 1800, it was evident that a choice was to be made; and implicitly, the Connexion decided to contain and channel local fervour: ‘inspiration’ was forced back inside an ‘institutional’ carapace. But a heavy price was paid.

In a letter of 1785, published in 1800, Mather had warned of the growing preponderance of ‘reason’ over ‘enthusiasm’:

Has not the attempt to avoid what has been called Enthusiasm, or the appearance of it, … been one grand cause of every revival of religion not continuing in its prosperity? And are we now in no danger from the same quarter? And have not many of our preachers and people, suffered much from it already? I greatly fear they have.Footnote 108

In 1791, a hostile pamphlet presented Methodism as a conspiracy against the vulnerable and gullible: ‘However enthusiastic, the Followers may be, the Leaders seem perfectly cool, and collected. There is a Semblance of Enthusiasm, but wary prudence regulates every step.’Footnote 109

In a series of moves in the early 1800s, the Conference sought to impose control by the preachers, and greater regularity of Methodist practice. In 1800 it moved to downplay emotional responses to religion, through this resolution:

Q.13. Do we sufficiently explain and enforce practical religion, and attend to the preservation of order and regularity in our meetings for prayer, and other acts of Divine worship?

A. Perhaps not. We fear there has sometimes been irregularity in some of the meetings. And we think that some of our hearers are in danger of mistaking EMOTIONS OF THE AFFECTIONS for experimental and practical godliness. To remedy or prevent, as far as possible, these errors, let Mr. Wesley's Extract of Mr. Edwards's pamphlet on Religious Affections be printed without delay, and circulated among our people.Footnote 110

In 1802 Conference addressed a number of ‘evils’ including standing or sitting at prayer: ‘We strongly recommend it to all our people to kneel at prayer; and we desire that all our pews may, as far as possible, be so formed as to admit of this in the easiest manner.’Footnote 111 (It was not until 1820 that Conference adopted regulations for ‘public prayer meetings’, and then only ‘when prudently conducted by persons of established piety and competent gifts, and duly superintended by the Preachers, and by the Leaders’ Meetings’.Footnote 112) In 1803 strict limits were imposed on women preaching,Footnote 113 while a series of regulations in 1805 reasserted preachers’ rights over music in chapel: ‘Let no Preacher suffer any thing to be done in the chapel where he officiates but what is according to the established usuages [sic] of Methodism’, insisted the Conference.Footnote 114

In 1800 the Methodist Magazine printed a depressing manifesto for the movement's increasingly pervasive rationalism:

But while the men of the Methodist leadership implemented a cautious strategy of managed growth, careful resource management and social respectability (notably under Jabez Bunting), some members continued to prioritize the spontaneous promptings of the Holy Spirit, as found throughout the whole community of saints. For them, and for women preachers driven from the Wesleyan mainstream, new opportunities to advance the kingdom of God were emerging in an increasingly fissiparous Methodism, notably in Primitive Methodism.Footnote 116