Introduction

Public policy is a common tool that governments use to deliver public services, boost the economy and maintain social order. Policy change reflects the shift of the priorities of decisionmakers on economic, social and other issues and shows how the political system processes and responds to new problems. To some extent, policy change reflects the capacity of a regime to rectify policy problems and adjust to new demands and situations.

In democratic countries, actors inside and outside the state have various channels for expressing their concerns and influencing policy agendas. In contrast, in authoritarian countries, such as China, less inclusive institutions lead to different dynamics of policy change. Undoubtedly, policy change has been a critical element of China’s politics of the past three decades. Transformations in the economic, social and political fields have been achieved by a myriad of policy reforms. For example, in the 10 years between 2003 and 2013, China’s State Council and the National People’s Congress (NPC) passed 336 new policies, including regulations and laws. Reforms of the existing policies accounted for 58.3% of the total.Footnote 1 In a sense, this indicates that the government constantly adjusts to new problems and demands from society. It also suggests that policy reforms in China provide rich experience and material for study on policy change in an institutional environment different from that of open democracies.

Recent studies on policy change in authoritarian regimes suggest that due to the absence of elections and citizen participation, decision-making elites often ignore information from society, which leads to extended policy inertia, and policy change does not occur until policy conflict and pressure cumulate to dangerous levels. At the policy output stage, the centralisation of decision-making powers involves less institutional friction and reduces the cost of policy change, which implies that once decisionmakers initiate change, the policy change is radical and forceful. Accordingly, on the one hand, the dynamics of policy change in authoritarianism share universal characteristics with open democracies, such as long periods of stability interspersed with radical changes. On the other hand, owing to the institutional features mentioned above, policy punctuation is more pronounced in an authoritarian system than in democracies (Lam and Chan Reference Lam and Chan2015; Chan and Zhao Reference Chan and Zhao2016; Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Carammia, Epp, Noble, Rey and Yildirim2017). These studies largely extend our understanding on policy changes in authoritarian regimes, yet little work has been conducted to explore the government information processing mechanism underlying the macrolevel findings. How are conflicts and pressure built up under authoritarian systems? What factors cause the variation in policy outcomes; that is, why do some policy changes proceed quickly, whereas other policy changes are difficult to attain? These questions about policy change under authoritarianism remain fascinating but ambiguously answered. This study attempts to fill a gap in the knowledge on these questions by providing evidence from an in-depth case study of policy changes in China. This microlevel research responds to these questions, showing how pressure for policy change is built and grows prominent, triggers reaction from decision-making elites and overcomes resistance in an authoritarian country.

Although top leaders and bureaucrats are the main policy actors in China’s authoritarian political system (Lieberthal and Oksenberg Reference Liberthal and Oksenberg1988; Shirk Reference Shirk1993; Choi Reference Choi2017), scholars have recently observed the active and successful engagement of the media, think tanks, social organisations and other societal actors in the policy-making process. To varying degrees, social actors such as experts and nongovernment organisations (NGOs) assume roles to promote policy change by presenting information to decisionmarkers (Mertha Reference Mertha2008; Wang Reference Wang2008; Zhu Reference Zhu2008; Mertha Reference Mertha2009; Hess Reference Hess2010; Ma Reference Ma2012; Zhu Reference Zhu2013; Bondes and Johnson Reference Bondes and Johnson2017; Truex Reference Truex2018). Nonetheless, the existing findings have limits in explaining the unstable influences of societal actors on policy change. The involvement of the media and experts successfully promotes policy reform in some cases, while the influence of societal actors is marginal in other cases. It is worth exploring what factors contribute to this variation, what channels and strategies the state and societal actors have, and how their interaction affects the development of policy change. Using evidence from China, this paper aims to understand the dynamics of policy changes in an authoritarian regime and proposes a “conflict expansion model” to relate variations in processes and the outcomes of policy changes to the efforts of pro-reform forces and the opposition of pro-status quo forces. This paper focuses on the impact of conflict between pro-reform forces and pro-status quo forces on the policy change process – particularly on the way in which advocates build pressure for change, the barricades against change, the responses of decisionmakers and impact of the institutional foundation on these policy actors.

This paper is composed of six sections. Following the introduction section, the second section presents the conflict model and discusses the existing literature on policy change. The third section briefly introduces the research methods. The fourth section traces the policy change processes of four cases, with a focus on the advocates and opponents of policy change, their access channels, strategies and influences and the response of decisionmakers towards policy issues. The fifth section discusses the findings, compares the facilitating and resisting forces of policy changes among the four cases and analyses how conflict shapes the process and pattern of policy change. The last section presents the implications and limitations of this paper.

The “conflict expansion” model of policy change

The study of policy change dynamics is a well-developed tradition in the study of the US public policy and has been applied to other open democracies. The literature on policy change shares two important theoretical prepropositions, namely, bounded rationality (Simon Reference Simon1957, Reference Simon1985) and conflict expansion theory (Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1975). These path-breaking studies show both the difficulties and possibilities of policy change.

Bounded rationality and conflict expansion

The concept of bounded rationality notes that the serial attentiveness of decisionmakers does not allow them to consider all issues simultaneously. After making policy, decisionmakers tend to leave policy implementation to bureaucrats in the policy subsystem and move their attention to the next pressing issue. The status quo is difficult to disrupt until a policy problem becomes aggravated, and then decisionmakers reallocate their attention back to it (Bosso Reference Bosso1987; True et al. Reference True, Jones and Baumgartner2007). Human cognitive constraint, along with institutional friction, contributes to both long-standing stability and radical change (Jones and Baumgartner Reference Jones and Baumgartner2012). Recent studies have shown that this characteristic of information processing is shared with authoritarian governments as well (Lam and Chan Reference Lam and Chan2015; Chan and Zhao Reference Chan and Zhao2016; Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Carammia, Epp, Noble, Rey and Yildirim2017). Accordingly, policy change is not easy or frequent. Baumgartner and Jones (2010) propose the punctuated equilibrium theory and Kingdon (Reference Kingdon1984) develops the policy window mechanism to explain the occurrence of precious opportunities for policy change.

Despite the great difficulty and obstruction of policy changes, large-scale policy changes occur in many countries, including China. Conflict expansion forms a critical driving force to disrupt policy stasis. Policy change usually comes with the involvement of newcomers. Schattschneider (Reference Schattschneider1975) emphasises that the involvement of new actors fundamentally changes the power distribution within the conflict. Policy change involves the shift of policy priorities and the reallocation of various resources. Thus, a policy change could hurt the interests of those who have already benefited from the existing policy and favour others. The interests and preferences of actors involved in the policy change process diverge and even conflict with each other. In response, the dominant groups in the policy community would mobilise to resist change that is detrimental to their interests (Birkland Reference Birkland1998). The conflict expansion model suggests that the power distribution between two sides of a conflict shapes the course and outcome of policy change. Thus, if disfavoured groups want to challenge the policy subsystem, the most effective way is to make the conflict public. Although policy change is often obstructed by existing values, institutions and interests, if the pressure for policy change is sufficient, a policy subsystem that prefers the status quo to change would ultimately collapse (Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1975; Bosso Reference Bosso1987; Baumgartner and Jones 2010). An opportunity for policy change can be created by a crisis or an accumulation of problems, which mobilises the previously apathetic population from outside to join the policy debate (Jones and Baumgartner Reference Jones and Baumgartner2012). The conflict expansion leads to the increase in facilitating power.

Given the importance of newcomers, many studies have explored their characteristics, strategies and influences. Policy entrepreneurs (Kingdon Reference Kingdon1984) are groups of people who constantly focus on issues, advance them to the governmental agenda and prepare policy solutions. The existing research finds strong explanatory power of this theory in China’s policy-making process. Bureaucrats and experts actively facilitate policy innovation and change (Liu and Rao Reference Liu and Rao2006; Wang Reference Wang2008; Zhu Reference Zhu2008; Choi Reference Choi2017). In addition to policy entrepreneurs, the involvement of the media is instrumental for policy change. In our time, the media is the most effective means to expose problems and mobilise previously indifferent populations to join a conflict (Kingdon Reference Kingdon1984; Bosso Reference Bosso1987; Birkland Reference Birkland1998). Related to the impact of the media on policy changes, the mechanism of focusing events has been widely discussed in policy change studies. “Focusing events” are used to describe unanticipated, sudden, attention-drawing events, which increase issue salience, expose policy failures, and could be important tools for policy changes (Downs Reference Downs1972; Cobb and Elder 1983; Kingdon Reference Kingdon1984; Bosso Reference Bosso1987; Birkland Reference Birkland1997, Reference Birkland1998; Baumgartner and Jones 2010).

The notable influences of the media are observed not only in open democracies but also in authoritarian countries such as China. Despite censorship, commercialised mass media and internet create a public space for citizen participation and criticism of public policies (Mertha Reference Mertha2009; Shirk Reference Shirk2011; Ma Reference Ma2012; Yang Reference Yang2013). The involvement of policy entrepreneurs and/or the media can expose policy problems, mobilise pressure and trigger a chain reaction in policy change.

Conflict expansion and policy change in authoritarian regimes

The theories of conflict expansion and government information processing mainly focus on open democracies, as institutional openness is a precondition for the involvement of newcomers, conflict expansion and responsiveness of governments (True et al. Reference True, Jones and Baumgartner2007). Only when multiple institutions offer access to actors outside the policy subsystem are new participants able to join the conflict. Accordingly, the ubiquitous bounded rationality of decisionmaking and the distinctive characteristics of institutional arrangements shape the specific pattern of conflict expansion and policy dynamics in a country. Studies on policy change in authoritarian regimes argue that due to the absence of elections and an independent society, authoritarian governments have relatively lower incentives and fewer mechanisms to gather and respond to information from society (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Carammia, Epp, Noble, Rey and Yildirim2017). The confinement of citizen participation and political competition restricts conflict expansion and amplifies the cognitive bias of decisionmakers.

Within China’s political system, the one-party state excludes societal actors from sharing power. Nevertheless, public policies are frequently questioned and denied by the media, the public, experts and other societal actors (Ma Reference Ma2012; King et al. Reference King, Pan and Roberts2013). This puzzle raises an interesting question regarding whether societal actors influence policy change in China, and if so, how. Recent research on China’s public policy suggests that the policy-making process is currently more permeable than it was before (Wang Reference Wang2008; Zhu Reference Zhu2008; Mertha Reference Mertha2009). It is also worth mentioning that decisionmakers in China are very sensitive to the crises that can destabilise the regime (Truex Reference Truex2018). To preserve regime legitimacy and survival, decisionmakers consciously develop various measures to incorporate information (Yan Reference Yan2011). Thus, the regime appears tolerant of and responsive to public participation, criticism and conflict on policy issues (Ma Reference Ma2012). It seems that on the one hand, China’s authoritarian institution offers few formal mechanisms for public participation, while on the other hand, societal actors can find opportunities in the pluralistic society to build social pressure and join policy conflicts. At the same time, to mitigate information inefficiency, decisionmakers concentrate on risk control and hence appear sensitive to alarming signals from media reports, social pressure and other forms of conflict.

On the other hand, dominant groups in the policy community resist change that is detrimental to their interests. Recent studies on China’s policy-making processes have suggested that division within the ruling coalition delay the policy-making process, especially when the policy proposals are contradictory to their desired outcomes. Due to their obstructions, the policy-making process is protracted (Choi Reference Choi2017; Truex Reference Truex2018). From this perspective, the policy change process reflects the contest between the pro-reform forces and pro-status quo forces. These policy activities occur in political institution. Thus, authoritarian institutions, characterised by an uneven distribution of power, affect not only the rules of the game and the creation of new actors but also policy priorities, issue framing, discourse and the generation of new areas (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2008; Mahoney and Thelen Reference Mahoney and Thelen2010; Radadelli et al. Reference Radaelli, Dente and Dossi2012; Barbieri Reference Barbieri2015). The influence of institutions on the development of conflict and policy change process is significant and large.

In this sense, China’s experience presents an interesting test of the theories of conflict expansion and information processing founded in open democracies. Accordingly, drawing upon the rich literature on both policy change dynamics and China’s policy-making process, this paper proposes a conflict expansion model to understand the dynamics of policy change in China and more specifically the variations in the courses and outcomes of policy changes.

This study concentrates on conflict expansion and its impact on policy change with particular attention being paid to two factors in the conflict expansion process: information input and pro-reform forces; and pro-status quo forces and their resistance to change. The interaction between the facilitating force and resisting force accounts for variation in the processes and outcomes of policy changes.

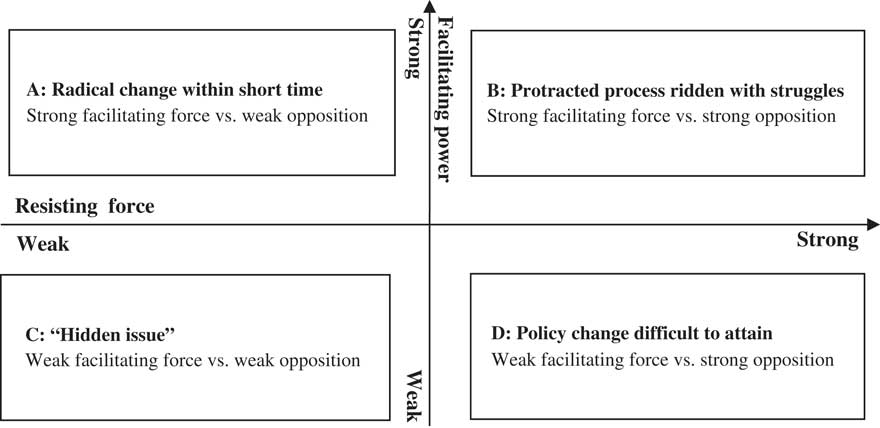

As Figure 1 shows, at the first step, when the pro-reform forces expand issues to broader audiences and build pressure for change, policy failure is exposed, and the opportunity for policy change emerges. Otherwise, policy problems remain invisible, and stasis is extended. In response, pro-status groups tend to contain the conflict and resist change. Top leaders are inclined to initiate policy changes when social pressure and discontent are so strong that further inaction might threaten regime stability (Joo Reference Joo1999; Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Carammia, Epp, Noble, Rey and Yildirim2017; Truex Reference Truex2018). Thus, the pressure for change should be sufficient to compel decisionmakers and to overcome resistance. Therefore, at steps 2 and 3, whether a pro-status quo force exists, and further if it exists, and whether its resistance is too strong to overcome are crucial to policy changes. When the resistance is absent or loosely organised, a radical policy change will occur more easily. However, if the resistance is so strong that pro-reform forces fail to overcome within a short time, policy change tends to be difficult and protracted.

Figure 1 Conflict expansion and policy actors.

The conflict expansion model develops two dimensions to measure the capacities of the facilitating force and the resisting force (Figure 2). The horizontal axis shows the level of political capacities of the resisting force. From the left to the right, the political power of the opponents grows stronger. The vertical axis shows the level of political capacities of the facilitating force. From the bottom to the top, the strength of the facilitating force grows stronger. Cells A, B, C and D represent four types of conflict in policy change. Each conflict pattern leads to different courses of issue development on the governmental agenda and policy formulation.

Figure 2 Power distribution between facilitating force and opposition.

In cell A, resisting force against policy change is weak, and a force directed at overcoming it is strong; policy change is forceful and quick. If, however, the strong facilitating power meets stubborn established interests, the pattern of policy change falls into cell B. As a consequence, the policy change undergoes a protracted process ridden with deadlocks and bargaining.

In cell C, the weak force fails to send an information signal into the system, which renders policy problems invisible. In this scenario, even if the resistance force is weak or absent, the policy issue remains a “hidden” issue excluded from policy agendas. Cell D stands for a situation in which policy change is most difficult, if not impossible. In this scenario, the established interest against reform is powerful, and the pro-change force is unable to overcome it.

The conflict expansion model posits that similar to policy changes in open democracies, long-standing policy stability is disrupted by radical policy change in China. Societal actors have large effects on promoting policy changes. However, due to institutional barriers, their participation is incident-based and unstable. Thus, when the established interest is recalcitrant, policy change is difficult and protracted. The process and outcome of policy change reflect the contest between pro-change forces and established interests within the authoritarian system, in which power is unevenly distributed. It also suggests that facing expanding conflict and the increasing severity of a policy problem, top leaders in China will initiate policy changes to prevent unrest and to maintain regime legitimacy.

Methods and case selection

This study traces the change processes of four policy cases. As a longitudinal study, it analyses the key actors involved the policy change process, their access channels, strategies, interests and influences. This research conducts extensive documentary research on published policy documents, memos, media reports and academic papers (see Appendix 1 for a list of documents). To gain a better understanding of the impacts of important actors and events on policy change processes, semi-structured interviews were conducted with officials, journalists and experts who were involved in four policy reforms. Six interviews with them are cited in this paper (see Appendix 2 for the full list of interviews). It is worth mentioning that the four cases in this study are high-profile cases. Thus, this study mainly relies on documentary research to collect data. In-depth interviews are supplementary tools for data collection.

The four cases are (a) the creation of the New Rural Cooperative Medical System (hereafter cited as NRCMS); (b) the reform of the Urban Demolition Regulation; (c) the reform of the Dairy Product Safety Standard; and (d) and the reform of the Environmental Protection Law. These are all national policies, for national policy provides a better and clearer perspective for observing the state’s response to society. Under China’s administrative system, local governments are directly accountable to upper level governments. Accordingly, when local officials address social pressure, the orders and attitudes of upper level governments are more important than the local problems (Cai Reference Cai2004; Edin Reference Edin2005; Gao Reference Gao2009). Instead, the decisionmakers of the central government are more independent in addressing social pressures and demands. In addition, national policy serves better for comparative study with other countries. Finally, in light of data availability, these cases are well known. The media has conducted a number of reports and interviews on the policy issues, and several valuable studies have uncovered inside stories of the policy processes. All of these important resources contribute to a better understanding of the policy change processes and make this multiple case study feasible.

The four cases share common aspects. There are significant differences before and after the reform. In addition, there are notable variations in terms of the length of the policy change process, the political capacity of the facilitating force and the obstacles to policy change. For instance, it took eighteen years for the RCMS reform to reach the governmental agenda and less than one year for the new Dairy Product Safety Standard. The new Urban Demolition Regulation and the new Environmental Protection Law encountered resistance from strong established interests, while in the other two cases, the resistance was relatively weak. Accordingly, the similarities and differences among the four cases construct the basis for a comparative study.

Four cases of policy reform

The policy change of the dairy product safety standard

In July 2010, the new Dairy Product Safety Standard (hereafter cited as new standard) was issued by the Ministry of Health to replace the previous standard established in 1986. In the new policy, the protein content was lowered from 2.95 g/100 g in the 1986 standard to 2.8 g/100 g (Ministry of Health 2010; hereafter MOH), which is considered a compromise to the present levels of China raw milk supply system.

In 2008, melamine, an industrial chemical used in flame retardants and other applications, was first found in the infant formula produced by China’s largest milk powder producer, Sanlu. After ingesting the Sulu infant formula, at least six babies died from kidney failure, 300,000 children had kidney problems, and 54,000 children remained hospitalised by December 2008 (Branigan Reference Branigan2008). In the subsequent test on 109 dairy companies, 21 companies were found to produce melamine-tainted dairy product, including other two dairy giants, Yili and Mengniu (CCTV 2008), and tainted dairy products ranged from baby formula to yogurt and ice cream. A myriad of news reports focusing on this issue persisted over several months, and the scandal even drew attention from the international community.

With the economy’s rapid development, dairy products in China have transformed from a luxury item to a common food staple (Yang Reference Yang2007). The outbreak of the melamine scandal exposed the chronic problem rooted in China’s dairy industry and supervision system. Due to reasons such as climate, cow breed and malfeasance in the supply chain, raw milk sometimes did not meet the protein content requirement of the 1986 standard (China Industry Research Center 2011). As a result, many farmers and middlemen added substances such as melamine into raw milk to artificially increase the protein content. Dairy products tainted with this substance can lead to kidney failure and other health problems and, even worse, can result in death (Fu Reference Fu2009).

The 1986 dairy protein standard was implemented under a planned economy in which the dairy market remained small in China, and the dairy industry consisted of collective or state-owned milk farms. By the 2000s, the market and environment faced by dairy producers and regulators was completely different from that of the 1980s. In light of China’s inferior dairy supply chain, the infeasible protein content requirement of the 1986 standard was one of the factors that led raw milk producers and middlemen to add additives such as melamine.

This public crisis caused widespread criticism of the poorly regulated dairy industry and the existing dairy safety system. To the leaders of the party state, public health and security crises are critical issues. Crises such as the melamine scandal (2008) and the prevalence of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) crisis (2003) can spur widespread fear and sometimes mass resentment across classes and regions. Therefore, China’s regime leaders are always highly responsive to public health and security crises.Footnote 2 For instance, after the 2003 SARS crisis, a crisis management system was established to appease grievances and fear efficiently. Under the enormous social pressure following the melamine scandal, once again, the state used policy innovations and reforms to show the public that the central government possessed the willingness and ability to rectify the dairy market. In early 2009, the Ministry of Health was charged with organising a cross-ministry committee to revise the standard (New Beijing Daily 2011).

The involvement of the media and dairy consumers across the nation significantly increased the pro-reform force, whereas the dairy industry split into several camps with different stances towards the reform of the standard. Giant dairy firms targeted the national market, and a large proportion of their products used the milk reconstituted from dried milk powder with a relatively low protein content. Local dairy firms produced fresh milk with a high protein content and relied on the raw milk supplied by nearby dairy farms. The new Dairy Product Safety Standard could increase the competitiveness of dairy giants and reduce the number of local small companies (Li Reference Li2011). Different interests and reactions towards the new standard prevented Chinese dairy firms from fostering a unified stance towards the policy change. As a result, the new standard was issued within one year.

In summary, since the food safety problem affected health, the core interest of people, the melamine scandal in 2008 mobilised enormous social pressure for policy change. Meanwhile, dairy firms were fragmented. As a result, policy change occurred efficiently and within a short period of time.

The reform of Urban Demolition Policy

In 2011, the State Council issued the Expropriation and Compensation of Buildings on Stated-Owned Land Regulation (hereafter cited as the “2011 regulation”) to replace the Urban Buildings Demolition Management Regulation (hereafter cited as the “2001 regulation”). The 2011 regulation gives homeowners an expanded right to protect their property rights before and during demolition, a right that was absent in the previous policy.

The 2001 regulation was made in the context in which the central government promoted city renewal and real estate development (Xie Reference Xie2009). The primary goal of policy makers was to ensure successful and effective urban demolition and land expropriation. Thus, the 2001 regulation had several deep-rooted problems in property rights protection. First, it did not give those whose homes or buildings were going to be demolished the right to participate in demolition decisionmaking. Second, the 2001 regulation provided local governments with the authority to conduct administration-forced demolition.

As the 2001 regulation violated their rights and interests, urban homeowners started questioning and challenging the existing policy, and they were joined by lawyers and legal scholars. In 2003, a group composed of 116 homeowners, lawyers and legal experts petitioned the Standing Committee of the NPC to revise the 2001 regulation. In response, the NPC and the Ministry of Construction performed an investigation and ultimately turned down the request (Sheng Reference Sheng2003).

The 2007 Chongqing nail house incident was an important event in the policy change process. A couple, Wu Ping and Yang Wu, owned a two-story building in Chongqing, a metropolis in southwestern China. In 2005, they were informed that the neighborhood was going to be seized by the local government for redevelopment. This couple stayed because they were unsatisfied with the compensation offered by the developers. As a consequence, their house stood on at mound surrounded by the construction site and excavators. It looked like a stubborn nail that was hard to pull out of the land. This picture and story were posted on the Internet and circulated immediately. A number of international and domestic news agencies reported the incident. After that, forced demolition was no longer defined as an isolated problem that affected only a few home owners in certain regions but was considered a national issue.

In response to this incident, on December 14, the State Council set reform on the policy agenda (Yang Reference Yang2009). However, two drafts were both rejected in 2008. As legal scholars noted, a strict new policy would hinder most urban demolitions with commercial purposes, which would inevitably reduce local land revenue and influence economic development (Ye Reference Ye2009).

The 2009 Chengdu forced demolition incident brought the demolition policy reform back to the policy agenda. Tang Fuzhen, a female resident, set herself on fire to resist the demolition of her family-owned building in Chengdu, Sichuan province. Her neighborhood was seized by the municipal government for the construction of new public infrastructure. Tang’s family refused to leave and continued to occupy the building for more than two years (Wu Reference Wu2011). Finally, after two years’ delay, the administratively forced demolition was ordered. News of the resulting suicide was immediately disseminated by Weibo, a new microblogging social media in China, and aroused nation-wide indignation and sympathy. Subsequently, five scholars from the Law School of Peking University sent a petition letter to the Standing Committee of the NPC for a policy review on the existing demolition policy. This request was accepted, and the State Council started the policy formulation procedure within 10 days (Chen Reference Chen2009).

This was the second time that this policy issue had been set on the governmental agenda, and once again it was met with solid resistance. Under China’s land ownership system, urban land is owned by the state, and municipal governments have de facto authority to expropriate and transact land. Land revenue stands out as the major nonbudgetary income of local governments (Yuan Reference Yuan2005). In essence, local governments and the real estate industry formed a community with shared interests. They had strong incentives to keep the status quo. In addition, local officials had many institutional channels to influence the policy-making process and could send a “policy suggestion report” (zhengceyijianshu), which is an important means the central government uses to assemble concerns from local governments in the policy formulation process. Before policy drafts were brought to the general meetings of the State Council or for the voting of the NPC, policy makers sent reports to provincial governments and several important municipal governments, and local leaders were required to reply to the reports with comments, suggestions and criticisms.Footnote 3

Established interests blocked reform in 2007 and 2008, but they failed in 2009. In January 2011, a new demolition regulation that aimed to protect the interests and rights of property owners in urban demolitions was issued by the State Council.

In this case, serial focusing events related to urban demolitions mobilised the previously indifferent population to press for policy change. Although the facilitating force grew stronger as the conflict expanded, it met mighty resistance from the established interests. As a result, the policy issue rose and fell as a priority on governmental agendas, and the policy change was interrupted by bargaining and deadlock.

The reform of the Rural Cooperative Medical System

The NRCMS is a government-funded health insurance program that provides affordable health insurance and assistance to the rural population (National Health and Family Planning Commission 2013). It was formulated in 2002 to replace the traditional rural cooperative medical system (hereafter cited as RCMS). The involvement of leading officials was crucial to facilitate policy change.

China has adopted a dual welfare system. The government-funded healthcare used to cover only urban China (Choi Reference Choi2017), while rural residents received basic healthcare from community-based RCMS. In the mid-1970s, the RCMS covered 90% of administrative communes in China (Liu Reference Liu2004). However, in 1983, this health insurance program collapsed in most regions, as its financial base, commune revenue, was dismantled under the great rural economic transition from a collective economy to a household contract responsibility system. Approximately 90% of the rural population was uninsured in the following two decades (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Rao and Hsiao2003). Rural families faced public health deterioration (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Zhu, Wang and Zhang1994) and poverty caused by high medical costs (Ministry of Health 1993).

Despite the large number of uninsured people, the central government did not intervene. In the 1980s and 1990s, social welfare reform never occupied the centre of policy agendas. Furthermore, decisionmakers viewed the RCMS as the legacy of the Cultural Revolution and the planning economy, a symbol of misguided egalitarianism and communism.Footnote 4 They believed that rapid economic growth in rural areas would automatically improve peasants’ financial capacity to obtain access to high-quality medical services.Footnote 5

Meanwhile, as a disfavoured group whose interests were severely impaired by the poor operation of the RCMS, peasants took few actions to advance their health interests (Cao Reference Cao2009). Without sufficient communication tools and awareness, peasants had difficulties forming a unanimous health interest and bringing it to the national policy community (Bernstein and Lu Reference Bernstein and Lu2003).Footnote 6 Thus, domestic and foreign public health experts were the first groups to actively expose China’s rural health problems. Since 1983, domestic research institutes and international organisations have conducted a large number of investigations and presented policy suggestions to policy makers (see Appendix 3 for the list of research and surveys conducted by these organisations). However, the efforts of these experts do not directly reverse the policy preferences of the decisionmakers.

In late 2001, two important lobbies composed of leading officials thoroughly changed the perception of decisionmakers towards the RCMS reform. Zhang Wenkang, the head of the MOH, was a colleague of President Jiang Zeming during the 1980s in the Shanghai municipal government. Minister Zhang sent President Jiang a brief personal letter that was based on the research and conference cosponsored by the Asian Development Bank and the MOH on the rural healthcare problem. This letter received an instantaneous response from President Jiang (Liu and Rao Reference Liu and Rao2006). The other successful lobby was made by Li Jiange, the deputy director of the State Development and Planning Commission, the predecessor of the State Development and Reform Commission, which was in charge of studying and formulating policies for economic and social development. In December 2001, Li made a presentation at a top meeting held by President Jiang Zemin. This presentation focused on rural health problems and highlighted the low ranking of China (ranked 189 out of 191 countries) in health fairness in the 2000 WHO report (Zan Reference Zan2013).

Deputy Director Li and Minister Zhang possessed a formal connection or an intimate personal relation with President Jiang. Compared to regular public health officials and experts, they had better insights about what decisionmakers were most concerned about. In their lobbies, they related the absence of rural health insurance to rural impoverishment as well as social instability. This interpretation reframed the RCMS issue from a rural health problem to a critical social and economic issue that affected regime legitimacy. In this way, their lobbies successfully convinced decisionmakers to initiate reform immediately.

It is worth mentioning that there was no established interest in the policy subsystem. The Ministry of Finance (MOF) expressed budgetary concerns on a progressive rural healthcare policy (Cao Reference Cao2009; Zan Reference Zan2013). However, unlike established interests, the MOF had no incentive to obstruct change, especially when top leaders had decided to initiate reform. Thus, once the issue was set on the governmental agenda at the end of 2001, policy formulation proceeded quickly.

In this case, the disfavoured group failed to frame the issue on the media agenda and the policy agenda. The involvement of leading officials disrupted the 18-year policy stasis. As established interest was absent in the policy subsystem, the policy-making process could proceed quickly.

The reform of the Environmental Protection Law

The new Environmental Protection Law was promulgated in 2014 to replace the Environmental Protection Law of 1989 (hereafter cited as 1989 EPL). This policy reform responded to the escalating environmental problems and popular discontent with the ineffective environmental governance.

The 1989 EPL contained three major problems. First, it lacked penalty terms to punish polluting enterprises (Li Reference Li2015). Second, the 1989 EPL did not specify the environmental protection responsibilities of governments at various levels. Finally, citizens had no access to decisionmaking and supervision regarding environmental protection. As a result, stunning economic growth and ineffective pollution control resulted in a wide range of adverse environmental consequences.

The loose pollution control reflects the attitudes of decisionmakers towards the environmental issue. At that time, to a developing country such as China, environmental protection was the least important among the issues of poverty, employment and economic growth (Zhang and Zhao Reference Zhang and Zhao2013). Meanwhile, rapid and extensive industrialisation boosted the local economy and tax revenue, which propelled local governments to tolerate environmental deterioration and the misconduct of local industries. These factors produced a strong obstruction against policy change.

Before the late 2000s, public awareness of the environmental issue remained low.Footnote 7 Environment experts and NPC representatives first recognised the policy problems. From 1995 to 2012, 78 proposals were made by more than 2,400 representatives to revise the law (Wang Reference Wang2012). In response, the NPC organised more than 10 surveys for reforming the Environmental Protection Law and even sent lawmaking experts and officials to study environmental laws abroad (Wang Reference Wang2011). However, the decisionmakers did not initiate policy change.

This situation changed drastically in 2010 when the smog crises caused unprecedented social pressure and rage. In November, a twitter post by the US Embassy in Beijing sparked nationwide attention on air quality. The reading of Beijing’s PM 2.5 (particulate matter of less than 2.5 micrometres) went above 500 – approximately seven times the US standard for acceptable air quality. Chinese media aggressively reported on the issue, and the incident received nation-wide attention (Wong Reference Wong2013). Of the four cases, the air pollution issue was only issue that mattered for the health and lives of the entire population across Chinese regions. As smog occurred every winter, air pollution occupied the centre of the media and public agendas in the following years.

As increased public anger eroded regime legitimacy, after 18 years’ delay, the Standing Committee of the NPC initiated the legislative procedure of the EPL revision in January 2011. Due to the fierce interest disputes on environmental protection among local governments, industries, ministries, the NPC, civic environmental groups and experts, policy formulation proceeded slowly (Li Reference Li2013; Wang Reference Wang2014). Advocacy coalition made slow but important progress in the most debated fields. The final draft was passed by the NPC in 2014.

In summary, established interests monopolised the policy subsystem and resisted the policy changes raised by experts and NPC members for 18 years. After 2010, environmental crises created nation-wide pressure and greatly increased the driving force for reform; however, fierce conflict between different interests led to a protracted and difficult policy change process.

Analysis

The conflict expansion model shows how policy conflict, pressure and policy advocacy for change are built up under authoritarian regime. It also reveals the response of decisionmakers to policy problems and the resistance that advocacy efforts meet in policy change processes. As it is in many open democracies, large-scale policy change is a general characteristic in China’s public policy process.

This paper finds two approaches through which information input drives policy changes. One approach is the focusing event approach. Three out of four policy change cases are driven by this approach. In this approach, the media intensely reports public crises and provokes enormous social pressure for policy reform. The involvement of the media dramatically expands the scope of conflict and mobilises public support, strengthening the force of the disfavoured in the policy subsystem. The victims of the melamine scandal, forced urban demolition and air pollution intensified their voices by winning public support across the country via media reports and online discussions. Once decisionmakers identified the signals of public discontent and the risk of inaction, a decision to change the current policy was set on the policy agenda. Thus, citizen participation and the responsiveness of decisionmakers are two preconditions of the focusing event approach. In this sense, it confirms the views that public participation exists in contemporary China and that its influence in policy making is increasingly important (Mertha Reference Mertha2008; Ma Reference Ma2012). Before the Internet prevailed in China, information was monopolised by the state, and the policy-making process was highly exclusive (Wang Reference Wang2008; Shirk Reference Shirk2010). Citizens had few access channels to expose problems or connect with others to expand issues. As case studies in this paper illustrate, social media today not only provides media-savvy urban residents with relatively diverse access to information but also creates a platform for residents to express their concerns and to create pressure. In the face of prominent pressure from focus events, to stave off crises, regime elites respond to public discontent more effectively and in a timely manner (Nathan Reference Nathan2009; Truex Reference Truex2018). Under this environment, public participation is more active, with new communication tools that were absent before.

However, when policy issues capture little interest from the media and public, such as the rural healthcare issue in this study, the other approach – the elite advocacy approach – is pivotal to policy change. The elite advocacy approach is initiated by leading officials with an intimate relationship with decisionmakers and a solid professional background. Assuming the role as policy entrepreneurs, they expose policy problems that were previously neglected by top leaders. The successful lobbying of leading officials depends on their close connection to top leaders and their accurate understanding of the preferences and core interests of the top leaders.

The focusing events approach, along with the elite advocacy approach, plays a central role in exposing problems and building pressure for policy changes. Nonetheless, due to institutional disadvantages, these information input approaches are not always effective and reliable. Social actors excessively relied on media to express grievances. Formal venues offered by the institution are proven to be either ineffective or unavailable. The advocacy efforts through mailing petition letters and legislative proposals and submitting research reports were rejected or shelved by decisionmakers. It is worth noting that the abilities of citizens to use media to advance their interests vary considerably by population. In contrast to successful media campaigns promoted by their urban counterparts, uninsured rural families drew little attention from media, although their population was the largest of the four cases. There is a significant gap between the well-educated urban citizens and the rural population in terms of the ability to frame issues in the media. In addition, even in cases affecting urban residents, the impact of media is sporadic. The media’s attention to crises and incidents both rises and recedes quickly (Downs Reference Downs1972). No issue can occupy the media agenda for a long time. This shortcoming, along with China’s media censorship, restricts the media and the public from building persistent pressure to facilitate change. This feature is particularly illustrated in the case of urban demolition policy. The 2007 nail house incident created an opportunity to set urban demolition policy reform on the policy agenda. However, after public enthusiasm regarding this incident dwindled, policy reform was hindered by resisting forces, and the policy issue fell from the policy agenda.

Accordingly, the findings on information input show that in the crisis-responsiveness context of authoritarian regimes (Truex Reference Truex2018), media and public participation are crucial to compel decisionmakers to launch policy changes. However, these factors did not overcome the informational inefficiency of authoritarian regimes (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Carammia, Epp, Noble, Rey and Yildirim2017). Failures to expose problems on a timely basis and to compose persistent pressure contribute to policy inertia.

In addition to information inefficiency, the opposition of a pro-status quo group also obstructs or delays policy changes. This study suggests that this variation in the outcome of policy changes can be explained by interaction between advocates and resisting forces. Unlike the pro-change groups, which excessively rely on informal venues, established interests are state actors or other stakeholders, such as local governments, real estate industries and state-owned industries, which gain direct institutional accesses to influence policy processes. Buttressed by the institutions, they are more capable of mobilising into stable and persistent resistance to change. Only continuously accumulated public discontent and pressure are able to overcome it.

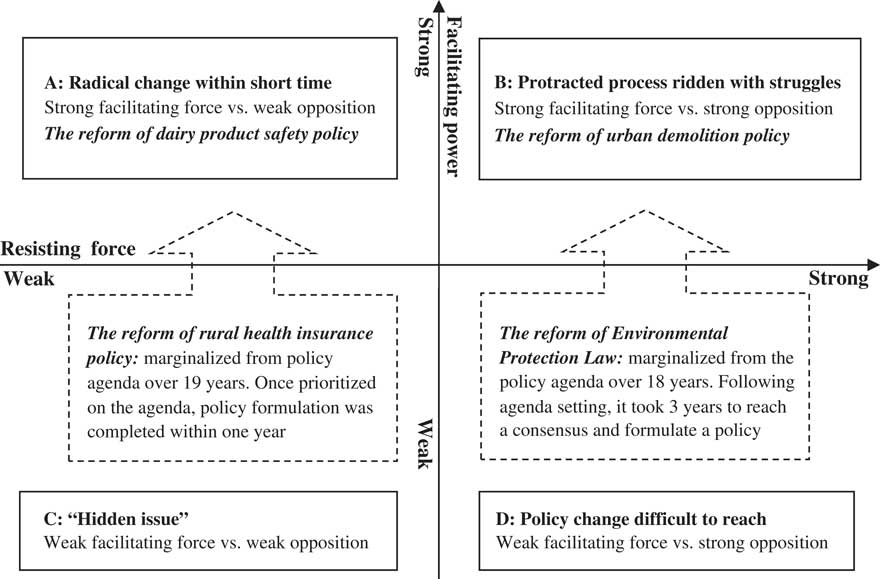

The authoritarian institutional arrangement shapes the capacities of two key forces in the conflict. Policy change is most likely to occur when the information signal from the external world is extraordinarily strong, and established interest is either fragmented or absent. It is more difficult for policy change to occur when the established interest is the state itself, and the facilitating force is politically weak (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Development of conflict between facilitating force and opposition.

Accordingly, the Dairy Product Safety Standard reform fits into cell A, as the outbreak of the melamine scandal mobilised nation-wide criticism of the existing policies. The pro-reform force was much stronger than the fragmented dairy industry, and policy reform occurred easily. The urban demolition policy reform fits into cell B. Although urban demolition incidents also stirred nation-wide controversies on policy issues, the resisting force composed of local governments and the real estate industry was at least as mighty as the advocates of policy reform. As a result, the policy change process moved back and forth.

The creation of new rural health insurance fits into cell C. The peasants were less capable of framing issues on the media agenda or the policy agenda, which led to a long period of government inaction. However, when the 18-year policy stasis was ultimately disrupted by the involvement of leading officials favouring policy change, the reform moved quickly, for there was no real-established interest in the policy subsystem. As Figure 3 shows, the case of rural health insurance reform moved from cell C to cell A. In the new Environmental Protection Law case, after long-standing policy inertia, smog crises mobilised a strong and persistent social pressure for policy change, which overcame the recalcitrant resistance. The change in the power distribution made this case shift from cell D to cell B. The findings illustrate that the development of policy conflict between the facilitating and resisting forces influences the course and outcome of policy changes.

Concluding remarks

This research seeks to understand the dynamics of policy change in an authoritarian context. Tracing the processes of four policy changes, this paper finds successful policy advocacy by leading officials and social pressure that comes from focusing events facilitate policy changes. In particular, focusing events play a crucial role in exposing problems, mobilising social pressure and ringing alarm bells for decisionmakers.

In addition, this paper finds that the processes and outcomes of policy changes are different. Some policy changes occur in a short period of time, whereas others undergo protracted processes. The conflict expansion model suggests that the variation in the course of policy change is influenced by the contest between pro-change forces and pro-status quo forces in the authoritarian institutional contexts. Societal actors can find opportunities to form social pressure for policy change. However, as China’s political institution offers such actors few effective formal venues, most participatory actions are undertaken through informal mechanisms (Tsai Reference Tsai2007; Ma Reference Ma2012). When established interests happen to be fragmented or absent, the policy change is radical and forceful. However, if the opposition to reform is very strong and solid, social pressure does not appear to be persistent enough to prevail over the resisting force within a short time. Within the uneven power-distributed political system of authoritarian regimes, aside from the informational disadvantages mentioned above (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Carammia, Epp, Noble, Rey and Yildirim2017), the resistance from dominant groups contributes to delay and under-response in policy change processes as well. This outcome implies that when the policy change comes to impair a core interest of the regime, such as reform of giant state-owned enterprises, the resisting force from the state will be difficult to overcome. Policy change is most likely to occur when the involvement of leading officials and/or the media increases the power of the pro-change force, while the established interest is not sufficiently strong to resist change. This model can not only explain the policy change processes of these four cases but also analyse other national policy changes with similar conditions. It can also be generalised to policy changes in other countries where institutions are less inclusive and public participation is quite active.

This study extends the applicability of theories of conflict expansion and government information processing to authoritarian countries. From the microlevel, this study demonstrates the process of pressure building up and information inputs and processing in authoritarian settings. This study suggests that similar to observations of other authoritarian regimes, China’s information input channels remain limited and not always effective. Therefore, under-response and delay are extended, and radical change occurs when problems grow severe, and the pressure for change destabilises the regime (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Carammia, Epp, Noble, Rey and Yildirim2017).

This study has limitations in exploring the concrete mechanisms decisionmakers adopt to gather and process information from the external environment, particularly from the media, as well as the mechanism to correct information hiding, manipulation and distortion in the transmission of information between different levels of government (Minzer Reference Minzner2009; Chan and Zhao Reference Chan and Zhao2016). Future research studies in this field would deepen our understanding of authoritarian government information processing and decision-making models.

Acknowledgements

Helpful and critical comments from the following persons on earlier versions are gratefully acknowledged: Suzanne Ogden, Christopher Bosso, Min Ye, Tom Christensen. Funding Source: 2015Z014, 17JZD008.

APPENDIX 1: List of documents

Government Documents

Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party and State Council (1997) Decision on the Development and Reform of Medical Service. http://govinfo.nlc.gov.cn/jssfz/xxgk/jsswst/201210/t20121009_850464.shtml?classid=464 (accessed 10 January 2014).

Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party and the State Council (2002) The Decision on Reinforcing the Rural Medical Service. http://cpc.people.com.cn/GB/64184/64186/66690/4494540.html (accessed 10 May 2013).

Ministry of Health (2010) New Dairy Product Safety Standard. http://www.moh.gov.cn/mohbgt/s10787/201004/46935.shtml (accessed 10 January 2014).

Ministry of Health (1993) Report of The First National Medical Service. http://www.moh.gov.cn/mohwsbwstjxxzx/s8211/201009/49159.shtml (accessed 12 February 2014)

Ministry of Health (1998) Report of the Second National Medical Service. http://www.moh.gov.cn/mohwsbwstjxxzx/s8211/201009/49160.shtml (accessed 12 February 2014).

National Health and Family Planning Commission (2016) 2015 Health and Family Planning Development Statistic Report. http://news.xinhuanet.com/health/2016-07/21/c_129166225.htm (accessed 7 August 2016).

Standing Committee of National People’s Congress (1989) Environmental Protection Law. http://www.npc.gov.cn/wxzl/gongbao/1989-12/26/content_1481137.htm (accessed 7 August 2016).

Standing Committee of National People’s Congress (2014) Environmental Protection Law (Revised). http://www.npc.gov.cn/wxzl/gongbao/1989-12/26/content_1481137.htm (accessed 7 August 2016).

State Council. 1991. Urban Land Buildings Demolition Regulation 1991. http://www.people.com.cn/item/flfgk/gwyfg/1991/112511199111.html (accessed 2 October 2013).

State Council. 2001. Urban Land Buildings Demolition Regulation. http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2001/content_60912.htm (accessed 2 October 2013).

Wang P. (2014) From Small to Big Change. June 5. The National People’s Congress Journal. http://npc.people.com.cn/n/2014/0625/c14957-25199658.html (accessed 2 November 2015).

Memo

Xie J (2009) Ten Years in Real Estate. Beijing: China Market Press.

Media reports

CCTV (2008) China Seizes 22 Companies with Contaminated Baby Milk Powder. CCTV, September 17. http://news.xinhuanet.com/health/2008-09/17/content_10048684.htm (accessed 15 January 2014).

Chen F et al. (2011) The Document of the Policy Making Process of the New Demolition Regulation [Xin Chaiqian Tiaoli Chutai Jishi]. Xinhuanet [Xinhuawang], (January 28). http://politics.people.com.cn/GB/1026/13834168.html (accessed 7 January 2014).

Chen F (2009) The Legal Affairs Office of State Council is Collecting Feedback of New Regulation and Promises to Revise the Policy Soon. Xinhuanet[Xinhuawang]. December 17. http://www.ln.xinhua.org/2009-12/17/content_18520355. 154918275361.shtml (accessed 10 January 2013)

Li B (2011) New Dairy Product Standard is Blamed to Benefit Giant Dairy Companies [ruping xinguobiao suoruyanzhong beizhi qianjiu bufen daxing ruqi]. China Securities Journal [Zhongguozhengquanbao]. June 27. http://finance.people.com.cn/GB/15002710.html (accessed 8 January 2014).

Li W (2015) New Environmental Protection enacts since January [zuiyan huanbaofa yanzai nali]. Economic Daily News [Jingjiribao]. May 6. http://theory.people.com.cn/n/2014/0506/c40531-24979845.html (accessed 2 November 2015).

Li Y (2013) Bargaining on the Environmental Protection Law Revision [huanbaofaxiuding zai baoyi]. China Business [Zhongguojingyingbao]. April 20. http://finance.ifeng.com/news/macro/20130420/7935941.shtml (accessed 2 November 2015).

New Beijing Daily (2011) Policy Formulation of National Food Safety [guojiashipin anquan zhengcezhiding]. New Beijing Daily [Xinjinbao], December 16. http://news.xinhuanet.com/politics/2011-12/06/c_122381206.htm (accessed 12 December 2013).

Sheng X (2003) Petitions from Hangzhou to Standing Committee of National People’s Congress. August 1. Law Service Time [Fulvfuwushibao]. http://www.china.com.cn/chinese/difang/377490.htm (accessed 10 February 2013).

Wang T (2012) Revising the Environmental Protection Law: full of advices[huanbaofa xiuding: yijian yiluokuang]. September 14. Nanfang Weekly [Nanfangzhoumo]. http://www.infzm.com/content/80777 (accessed 7 November 2015).

Wong E (2013) On Scale of 0 to 500, Beijing’s Air Quality Tops Crazy Bad at 755. New York Times. 12 January. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/13/science/earth/beijing-air-pollution-off-the-charts.html (accessed 16 February 2015).

Wu W (2011) The Homeowner Committed to Suicide Tragedy in A Forced Demolition, Yangcheng News [Yangchengwanbao]. December 3. http://news.dichan.sina.com.cn/2009/12/03/93050.html (accessed 2 January 2014).

Yang J (2007) The Forecast on China’s Dairy Industry Development: based on the growth in dairy consumption [Yuce Zhongguo ruye fazhan]. China Dairy [Zhongguoruye]:11-13.

Yang W (2009) Why does new demolition regulation delays? [weihe xinchaiqian diaoli chidao?] China News Weekly [Zhongguoxinwenzhoukan]. July 22. http://news.sina.com.cn/c/2009-07-22/ (accessed 7 January 2014).

Ye T (2009) How does Real Estate and Local Finance Save China’s Economy?[fangdichan yu tudicaizheng ruhe zhengjiu zhongguojingji], Beijing: Citic Press.

Yuan J (2005) How Real Estate kidnaps China?[fangdichan ruhe bangjia zhongguo]. June 15. http://club.kdnet.net/dispbbs.asp?id=778463&boardid=3 (accessed 1 February 2013).

Zan X (2013) Scholar-official Li Jiange[xuezhexing guanyuan Li Jiange]. Caixin Magainze [Caixin], January 28. http://magazine.caixin.com/2013-01-25/100486417.html?sourceEntityId=100662279 (accessed 6 March 2014).

Academic research

Cao P (2009) Two Attempts to Rebuild the Rural Cooperative Medical System in the 1990s and Their Consequences [20 shiji 90 niandai liangci chongjian nongcun hezuo yiliao de changshi yu xiaoguo]. Party History Study and Education [Dangshi yanjiuyujiaoxue] (4): 18–27.

Fu J (2009) The 2008 China Milk Scandal and the Role of the Government in Corporate Governance in China. University of Canberra. http://www.clta.edu.au/professional/papers/conference009/2FuCLTA09.pdf (accessed 8 January 2014).

Liu Y (2004) Development of the Rural Health Insurance System in China, Health Policy and Planning 19(3): 159–165.

Liu Y, Rao K and Hsiao W C (2003) Medical Expenditure and Rural Impoverishment in China Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition 21(3): 216–222.

Liu Y and Rao K (2006) Providing Health Insurance in Rural China: From Research to Policy Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Laws 31(1): 71–92.

Wang J (2011) The Environmental Protection Law Reform: from limits to effectiveness. Green Journal [Lv Ye](8): 34–37.

Zhang Z et al. (1994) The Review on the Rural Cooperative Medical System [nongcunhezuoyiliao huigui]. China Rural Medical Service Management 6(14): 4–9.

Zhang Z and Zhao B (2013) Twists and Turns of the Environmental Protection Law [huanbaofa quzhe]. Caijing Magazine, December 1. http://magazine.caijing.com.cn/2013-12-01/113631878.html (accessed 3 November 2015).

APPENDIX 2: List of interviews

SC1 12-2-13. State Council official, Beijing, China, 12 February 2013.

CASS1 9-1-14. Chinese Academy of Social Sciences expert 1 , Beijing, China, 9 January 2014.

CASS2 12-1-14. Chinese Academy of Social Sciences expert 2, Beijing, 12 January 2014.

HU1 6-5-14. School of T.H.Chan Public Health of Harvard University Expert, Boston, U.S., 6 May 2014.

Zan1 7-3-14. Journalist Zan, telephone interview, 7 March 2014.

CPPCC1 12-3-15. Member of Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference and environmental expert, telephone interview, 12 March 2015.

APPENDIX 3: Research and surveys on China’s health issue, 1983–2001

Source: Data are collected from academic papers, research reports and government reports and documents.