Introduction

As part of the debates about integrationFootnote 1, mosques, and their role in the integration of Muslims, the largest religious minority in Europe, have repeatedly been the subject of controversy. In Germany, around half of all Muslims are from Turkey (Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat 2020). A significant number of mosques belong to the Sunni umbrella organization, the DİTİB (Turkish-Islamic Union for Religious Affairs), which, in addition to running mosques, is also involved in the organization of religious education in public schools, language courses, and social and youth work (Kortmann and Rosenow-Williams Reference Kortmann and Rosenow-Williams2013). The first DİTİB association was founded in 1982 with the aim of providing a religious infrastructure in Berlin for immigrants from Turkey. Two years later, the association in Cologne was officially founded and later became the central structure (Rosenow Reference Rosenow, Halm and Sezgin2013; Beilschmidt Reference Beilschmidt2015, 49). The DİTİB has been partly supported by the German government (e.g., through integration projects and the organization of religious education, Deutscher Bundestag 2019) and Turkey's Directorate of Religious Affairs (the Diyanet) that sends imams. Critics have accused the DİTİB of being influenced by the Diyanet and of undermining the integration of the Turkish minority by sending imams from Turkey and strengthening ties with Turkey (Hür Reference Hür2018). It is also frequently described as the “extended arm” of the Turkish state. Further allegations concern connections to the Muslim Brotherhood, seen as a radical group (Landtag Nordrhein-Westfalen 2019), war propaganda against Kurds, and imams spying on members in order to uncover connections to Fethullah Gülen, whom Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan suspects to be the mastermind behind the 2016 military coup (e.g., Zeit 2016; Deutsche Welle 2018). In response, German government support has been substantially cut in recent years (Tagesspiegel 2017).

The DİTİB, as well as other Islamic religious communities, have been criticized for self-segregation and for creating a parallel society. The German government therefore expects them to promote integration and the German language and to address security issues in their mosques in order to prevent terrorism (Rosenow Reference Rosenow, Pries and Sezgin2010). Sermons and hate speeches in mosques as well as fragile international relations with Turkey were an issue in the German federal elections in 2017 (Maier et al. Reference Maier, Maier, Faas and Jansen2017).

In light of the links with the Diyanet and the Turkish state, this study examines the content of the sermons published on the DİTİB website. Currently, the sermons are written by imams in Germany and distributed in around 910 mosques. These imams belong to the Diyanet as well. We are interested in the content of these sermons. More specifically, the aim of this study is to answer the following two overarching research questions: First, “to what extent are relations with Turkey reflected in the sermons?” The sub-question is: To what extent does this vary over time? The term home (Heimat) is understood here as “a place where you feel at home” (Bundeszentrale fuer politische Bildung 2010). Our second research question reads as follows: “How is the concept of “home” reflected in those sermons?” For this purpose, a novel database was created, containing around 481 Friday sermons which were published once a week between 2011 and 2019. They were published in German and Turkish; we focus on the sermons in German. The Friday prayer is the most important prayer of the week and is mandatory in Islam if the conditions are met. It is intended to strengthen cohesion among Muslims and it has an educational function and a moral component to promote the spread of good and prevent bad (DİTİB 2021). We combine a quantitative and a qualitative content analysis of the Friday sermons.

While our analysis presents the case of Germany, our findings are also highly relevant for other countries, which increasingly debate the integration of Muslim minorities, host Turkish minorities and/or have outsourced the organization of religion to immigrants' home countries. This primarily concerns the Western European states but, more recently, the Diyanet has reinforced its influence in the United States in response to the expansion of Gülen's Hizmet movement (Aksel Reference Aksel2019, 161f.). By analyzing the content taught in mosques, our study contributes to the understanding of the role of home states when it comes to the integration of religious minorities in the Western hemisphere, state-religion relationships in a transnational context, and international relations. To the best of our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive content analysis of DİTİB Friday sermons over a 9-year period.

Theoretical framework

In classic assimilation theory, the joining of receiving society organizations and institutions is termed structural assimilation (Gordon Reference Gordon1964). However, in contrast to classic integration theories, the more recent approach of transnationalism assumes that immigrants and their descendants continue to live in transnational spaces between the country of origin and the country of residence. Transnationalism analyzes “cross-border ties of individual and collective agents, such as migrants, migrant associations, multinational companies, religious communities” (Faist Reference Faist2012, 51). The DİTİB navigates in such a transnational space between the Diyanet/Turkey on the one hand and Germany on the other.

At the organizational level, this implies that connections with the country of origin continue to exist due to cultural, religious and economic interests. Existing research has repeatedly raised the question of the extent to which there are transnational ties between Turkey and migrant organizations in Europe (e.g., Mügge Reference Mügge2012; Rosenow Reference Rosenow, Halm and Sezgin2013). Transnational connections can be beneficial for these organizations in achieving efficiency and legitimacy (Rosenow Reference Rosenow, Halm and Sezgin2013). For a long time, various European countries, including Germany, failed to incorporate the needs of Turkish minorities and left the fulfillment of religious needs to the states of origin. This resulted in associations that promote homeland ethno-cultural identity in what Ögelman (Reference Ögelman2003) referred to as “sending country leverage associations”. In the case of Turkish minorities, the Diyanet stepped in by sending imams. The aim was to promote religious and national identity, and to prevent the division of the community (Gorzewski Reference Gorzewski2015, 108f.). The structural interdependencies between the Diyanet and the DİTİB continue to exist throughout the governance structures of the latter organization, in which Diyanet members occupy central roles, including the president (Beilschmidt Reference Beilschmidt2015, 51f.). The Diyanet has played a key role in controlling religious affairs in Turkey since its foundation as part of the modern Turkish Republic, which promoted secularism in society (Rosenow Reference Rosenow, Halm and Sezgin2013).

With Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's election, this has slowly reversed and the criticism that he propagates a less progressive Islam has increased (Karaveli Reference Karaveli2016). The engagement of Turkey with its diaspora has intensified since his election, for instance, due to the weight of immigrant votes in Turkish elections, a perceived need to protect them from Islamophobia and Turkey's bargaining power when it comes to visa freedom in exchange for hosting refugees (Maritato Reference Maritato2018; Arkilic Reference Arkilic2021). Part of this diaspora engagement was the revision of citizenship rights, which meant that the diaspora had rights but also duties (Yanasmayan and Kaşlı Reference Yanasmayan and Kaşlı2019). The Presidency for Turks Abroad and Related Communities (YTB) was founded during this time (Göğüş Reference Göğüş2018).

The Diyanet, once an institution for controlling domestic religion due to the political nature of Islam, has turned into a foreign-policy instrument to control the religion of Turkish immigrants abroad, as Çitak (Reference Çitak2010) argues. Under the Justice and Development Party (AKP—Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi), the Diyanet's budget has increased, the organization has become directly attached to the presidency, more space on radio and TV has been granted and spiritual counseling in public institutions has been supported, all leading to increased power. The International Theology Program, linked to the Turkish Diyanet Foundation, established a link to fund education for Turks inside and outside of Turkey. The call for prayers following the military coup in 2016 (Çitak Reference Çitak, Bedirhanolu, Dölek, Hülagü and Kaygusuz2020), political campaigning in the context of prayers in Istanbul (Seufert Reference Seufert2020), the overproportional funding of religious schools, the altering of school textbooks and AKP's instrumentalization of fatwas (Yilmaz Reference Yilmaz and Akbarzadeh2021), amongst others, made the link between politics and religion further visible. Analyses of Diyanet sermons in Turkey reveal an increasing politicization since the rise of the AKP (Ongur Reference Ongur2020; Yilmaz and Barry Reference Yilmaz and Barry2020). The link between politics and religion in Germany occasionally becomes apparent. In the 2015 general elections, DİTİB imams served on balloting committees as, legally, they are civil servants who need to be represented at the ballot box (Yener-Roderburg Reference Yener-Roderburg, Kernalegenn and van Haute2020).

However, the DİTİB does not present itself as a representative of political Islam. In addition, the organization emphasizes its integration-promoting side, although it does not see itself as an integration service. The focus is on religious services. Nevertheless, the association is involved in the religious-political discourse to represent Muslim interests (Beilschmidt Reference Beilschmidt2015, 60f.). Showing the German flag next to the Turkish flag (Beilschmidt Reference Beilschmidt2015, 144), or having a bilingual internet presence symbolizes its roots in both countries and the hybrid identity of the organization (Rosenow-Williams Reference Rosenow-Williams2014). This also becomes visible in the simultaneous publishing of the sermons in German and Turkish, as German politicians have repeatedly called for German to be spoken in mosques (Zeit Online 2020).

In 2010, Erdogan stated that assimilation was a crime against humanity (Süddeutsche Zeitung 2010). Accordingly, the preservation of the Turkish identity among emigrants (see also Öztürk Reference Öztürk2018), as well as religious identity, represent a potential point of conflict with the German model of assimilation (Yurdakul and Yükleyen Reference Yurdakul and Yükleyen2009). According to Beilschmidt (Reference Beilschmidt2015, 64), the DİTİB primarily sees Turkey as the home of its members. Patriotic tendencies are reflected in references to battles, singing the Turkish national anthem at public events and employing rhetoric that speaks of the fatherland (Beilschmidt Reference Beilschmidt2015, 144; Gorzewski Reference Gorzewski2015, 103, 116). Öcal (Reference Öcal2020) describes the metaphor of the Turkish state as a partially strict but caring father who is replaced by the DİTİB in the everyday life of migrant citizens. The DİTİB thereby reconstructs feelings of home and familiarity in a new environment which may have caused trauma through isolation, discrimination and foreignness. This adds the dimension of home as a feeling to the dimension of home as a place.

The German government has, at times, associated the DİTİB with moderate Islam, due to it being controlled by the Turkish state and its connection to the Diyanet (Bruce Reference Bruce2019, 92). In the eyes of the German government, this represented an advantage over other temporarily more influential organizations such as Millî Görüş. The latter perceives the Islam propagated by the Diyanet, as being controlled by the state, following the separation of state and religion by (the former president) Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (Bruce Reference Bruce2019, 83). For many years, Millî Görüş showed stronger political tendencies instead (Yurdakul and Yükleyen Reference Yurdakul and Yükleyen2009) and represented the main competitor for the DİTİB: it even had more imams in Germany before the 1980s (Bruce Reference Bruce2019, 86f.).

Nowadays, by contrast, there is an exchange of imams between these two organizations (Arkilic Reference Arkilic2020). Back then, however, the integration of Turkey in the religious accommodation of people from Turkey and the promotion of transnational activities was in line with Germany's understanding of citizenship, which was based on ancestry (Koopmans and Statham Reference Koopmans, Statham, Joppke and Morawska2003). Since the 1990s, however, the preferences of the German government have shifted away from outsourcing to the incorporation of Islam in Germany, in order to monitor religious practices more closely (Laurence Reference Laurence2012, Reference Laurence, Hunger and Schröder2016). New opportunity structures such as the German Islam ConferenceFootnote 2, the organization of religious education in public schools and the training of imams are evidence of this (Mushaben Reference Mushaben2010; Michalowski and Burchardt Reference Michalowski, Burchardt, Burchardt and Michalowski2015; Hunger and Schröder Reference Hunger and Schröder2016). The existing structures are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. DİTİB between Germany and Turkey.

As a result of its organizational structure, the DİTİB is confronted with the interests of the German and Turkish states as well as community members. It pursues an isomorphic structure by adapting to the external expectations of the Diyanet, German society, and members, and can thus legitimize itself. Accordingly, nationalist references to both the country of origin and integration issues should appear in the Friday sermons.

Previous research has paid comparatively little attention to the sermons. A quantitative study should be mentioned here which, however, dealt with the sermons from a theological perspective and with the representation of God (Gibbon Reference Gibbon2008). Beilschmidt (Reference Beilschmidt2015, 144) uses exemplary excerpts from the sermons and discusses Turkish nationalism. More recently, Oprea (Reference Oprea2020) carried out a content analysis based on the Friday sermons for the years 2019–2020 on the subject of radicalization. However, these studies did not account for temporal variation in the occurrence of references to the homeland due to the socio-political situation in Turkey. Yet, as organizations like the DİTİB are guided by norms according to sociological neo-institutionalism (Rosenow Reference Rosenow, Pries and Sezgin2010), references to the home country should therefore have a higher probability of occurring if the social situation in Turkey becomes more fragile and requires more social cohesion and common norms and values (reactive nationality).

The Socio-Political situation in Turkey

The socio-political situation in Turkey has been turbulent, with multiple coups and power struggles between the religious and Kemalists (Atatürk's followers) over the last century. With the AKP coming to power in 2002, an Islamic, but democratic, party took over. However, since the 2010s, Turkey has seen a strengthening of religious structures (Yilmaz Reference Yilmaz and Akbarzadeh2021). Erdoğan's power was cemented in the 2014 and 2018 presidential elections. Turks living abroad played a substantial role in the elections, being more in favor of the AKP and its policies than residents in Turkey (Yener-Roderburg Reference Yener-Roderburg, Kernalegenn and van Haute2020). Allegations against growing authoritarianism and erosion of secularism in Turkey culminated in the Gezi park protests of 2013. A subsequent failed military coup in 2016 paved the way for a shift to a presidential system, which further consolidated the president's power. Turkey has repeatedly been shaken by terrorist attacks, which further destabilized the country. To name but a few, in the same year as the coup, Atatürk airport became a target of terrorist attacks, a suicide attack took place near Hagia Sophia and there was a shooting at a nightclub in Istanbul on New Year's Eve. A year before, attacks had been carried out in Ankara outside the railway station and as well as in Istanbul.

The war in neighboring Syria has further destabilized the region since the beginning of the last decade, leading to an influx of Syrian refugees to Turkey, an escalation of the conflict with Kurdish groups striving for autonomy, and security threats posed by the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Interventions by the Turkish army in the Syrian Kurdish region in 2015 finally put an end to the peace process between the AKP and the Kurdistan Workers' Party PKK (e.g., Parlar Dal Reference Parlar Dal2016; Tumen Reference Tumen2016).

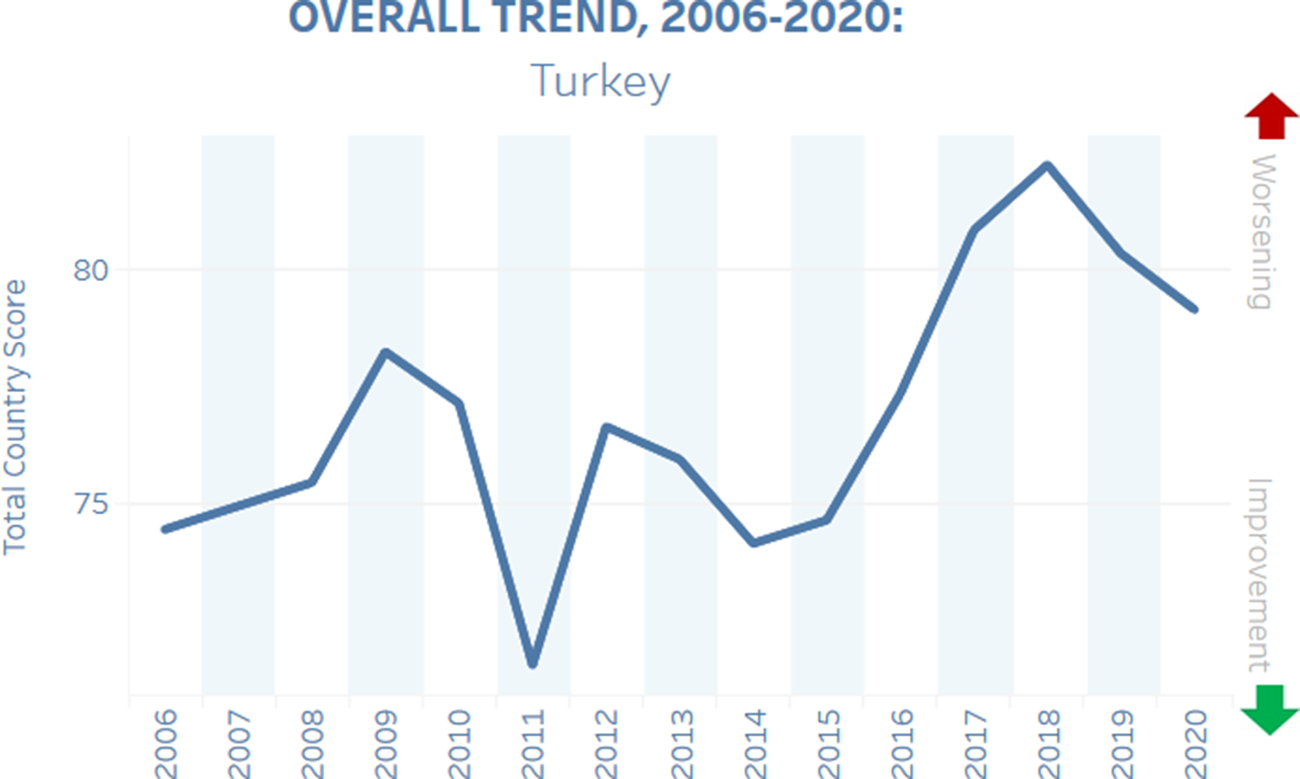

According to the Fragile States Index (Figure 2), Turkey's fragility increased between 2016 and 2018 in particular. This index captures the conflict risk in different countries from the point of view of four dimensions (cohesion, economy, politics and social). Each of these dimensions contains three sub-indicators. Each indicator can have a value between 0 (highest stability) and 10 (lowest stability). The sum of the individual indicators can reach a maximum value of 120, where 120 corresponds to the highest level of instability for a country (The Fund for Peace 2018). While the Fragile State Index varied around the 75 mark up to 2016, the score peaked in 2018 with 82 points, which suggests that the social situation in Turkey became more fragile within this period.

This suggests a higher likelihood of references to the homeland within sermons in 2018, coinciding with the shift to a presidential system in Turkey.

The Turkish minority in Germany

Germany has long been the main destination for people from Turkey. Around 2.9 million people of Turkish descent live in Germany. Most of them came as part of the guest worker agreement with Turkey in 1961. Subsequently, family reunions began (Schührer Reference Schührer2018). Since the failed military coup in Turkey in 2016, the number of asylum seekers has also increased (Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge 2019). While before the coup most applications were filed by Kurds, since the coup, former civil servants and Gülenists have also applied for asylum (Deutscher Bundestag 2021).

Socio-economically, people of Turkish descent are still disadvantaged in Germany. The level of education was, on average, lower than that of people without a background of migration. However, on average, the second generation obtains higher degrees than the first generation (Schührer Reference Schührer2018, 28). In a wide variety of societal spheres, people of Turkish descent frequently experience ethnic and religious discrimination (e.g., Carol et al. Reference Carol2019; Koopmans et al. Reference Koopmans, Veit and Yemane2019).

Most people of Turkish descent living in Germany are Sunni Muslims (74%), while approximately 14.5% are AlevisFootnote 3 (Pfündel et al. Reference Pfündel, Stichs and Tanis2021, 48). In a survey of Turkish immigrants and their descendants, 28% of the respondents said they go to a mosque and 45% said they pray. Overall, an intergenerational decline in religiosity can be observed. However, this does not hold for religious identification (Pollack et al. Reference Pollack, Müller, Rosta and Dieler2016). A recent study arrived at the conclusion that about 13% of the interviewed Muslims attend DİTİB mosques regularly but this was unfortunately not further differentiated by ethnic origin and is estimated to be higher among Turkish minorities, as the organization is more well-known among them (Pfündel et al. Reference Pfündel, Stichs and Tanis2021, 106, 114).

The Turkish minority identifies strongly with their country of origin. Around four out of five respondents belonging to the Turkish minority stated that they “very strongly” or “strongly” see themselves as Turks and that they are “proud” or “very proud” to be Turkish. A clear majority does not feel accepted and therefore does not identify with Germany (Jacobs Reference Jacobs2010). This means that identifying with Turkey and identifying with Germany do not necessarily go hand in hand. What are the implications of this for the sermons? As Turkish minorities in Germany mostly identify with Turkey but not Germany, sermons dealing with the topic of “homeland” should primarily relate to Turkey and not Germany. However, the identification of immigrants with Germany increased between the late nineties and the early 2000s (Hochman and Davidov Reference Hochman and Davidov2014). This, in turn, implies that we might see temporal trends in the sermons; with minorities increasingly identifying with Germany and with linguistic integration, over time, the focus of the sermons might also shift from Turkey to Germany.

Data, operationalization and methods

Our database contains 481 Friday sermons, which were published on the website www.ditib.de between 2011 and 2019. We focus on analyzing the sermons published in German but, for the sake of transparency, the DİTİB publishes a German and Turkish version. While we focus on the German translation, the Turkish translations use words with similar connotations, to the best of our knowledge.Footnote 4 We have coded the authors of the sermons, grouped by federal states, “committee for sermons” and “others”. However, no significant differences between federal states and the committee for sermons occurred (see Table A1 in the appendix). We chose 2011 as the starting point, as the sermons are accessible through the website from that year onwards. The investigated time period covers substantial religious and socio-political changes in Turkey.

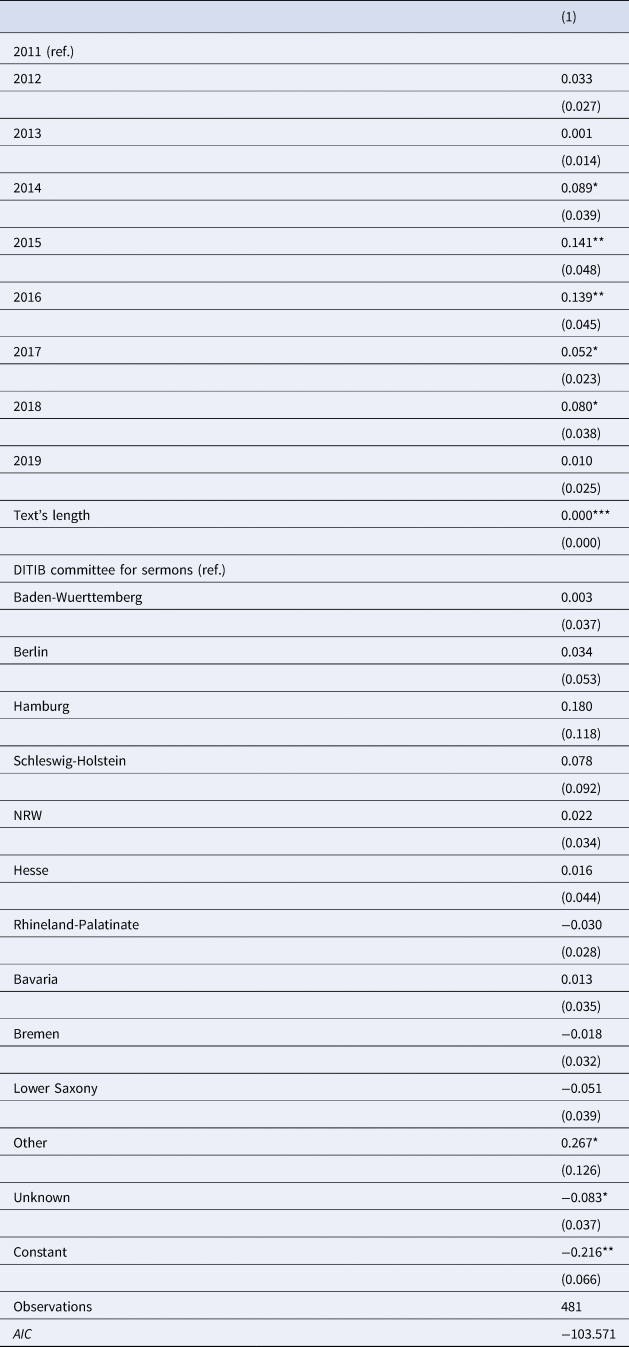

The data has been extracted and exported from the website using the Webscraper.io tool. The following analysis consists of quantitative and qualitative content analysis and follows the Explanatory Sequential Mixed Methods model, according to which, a quantitative analysis precedes a more detailed qualitative analysis (Creswell Reference Creswell2014, 15). With the help of a linear probability model with robust standard errorsFootnote 5, we examined the probability of a homeland-related issue for each year of publication. The variable is binary (0 “no homeland-related sermon”, 1 “homeland-related sermon”). This includes sermons that directly use the topic of home(land) or indirectly refer to the concept by mentioning the fatherland, the Diyanet and events in Turkey. We use the year of publication as an independent variable and control the text's length.

The relevant sermons were imported into the MAXQDA software for the qualitative content analysis. For this, we depart from Mayring (Reference Mayring, Flick, von Kardorff and Steinke2004). We created the categories using the concepts (e.g., homeland, integration etc.) and the data as the basis, and thus combined deductive and inductive coding to extract codes (Mayring Reference Mayring2000). While the basis for inductive coding depends on the content of the data, deductive coding is theory-based coding, with so-called in-vivo codes (Böhm Reference Böhm, Flick, von Kardorff and Steinke2004) being used in sermons. There is an overlap with summative content analysis, according to which, the occurrence of a concept, such as a homeland, and contextual changes in the texts are examined. The entire texts, as such, are not the subject of the analysis (Hsieh and Shannon Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005). In an iterative process, we created the codes on the basis of a partial sample, refined them in the process of coding and combined them into latent codes. An examination of the latent constructs in the content analysis also shifts the focus to words that occur in connection with the concept (of the homeland) and what the meaning behind those words is (Hsieh and Shannon Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005).

Quantitative content analysis

Figure 3 displays an overview of topics that are covered in sermons. Each sermon can contain multiple topics. Most sermons primarily contain references to theological topics and a discussion of the Koran.

Figure 3. Topics of the sermons.

The most common subjects that are discussed are mercy, the afterlife, love, sins, social cohesion (solidarity, trust, cooperation, peace and respect), serving, the pillars of Islam, and Ramadan. This is followed by a mixture of political and social issues, especially family issues. Homeland-related sermons make up a minority (5% of cases). Interreligious relationships and integration are discussed with a similar frequency (7% of cases). It should be noted that the mentioning of intergroup relationships and homeland are mostly addressed in separate sermons.

The topic of intergroup relationships correlates most strongly with the topics of democracy and gender equality/women's rights (Table 1). The probability of sermons mentioning intergroup relationships is significantly lower in the years 2015–2018 compared to 2011 (not shown). From the 1990s onwards, the Diyanet placed greater emphasis on interfaith dialog, mirroring Gülen's agenda. Yet this trend was, according to Yilmaz and Barry (Reference Yilmaz and Barry2020), reversed in the early 2010s. Along these lines, the topic of extremism gained in prominence, particularly during the years 2015 and 2016. One of the strongest correlations exists between extremism/terror on the one hand and discrimination/Islamophobia on the other hand (Table 1). The discussion of discrimination and Islamophobia in sermons reflects the anti-Islamic climate, with the rise of the German right-wing party, Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), the discrimination of Muslim minorities in Germany (Di Stasio et al. Reference Di Stasio, Lancee, Veit and Yemane2019), and attacks on Muslims (Zeit Online 2021).

Table 1. Tetrachoric correlations

Note: Only correlations with a significance level of at least 0.05 are displayed.

V13 = War and conflict in Islamic countries, V14 = Homeland-related issues, V15 = Democracy, V17 = Nature, V18 = Body odour/cleaning/health, V19 = Socialization and education, V20 = Work, V22 = Chastity, V23 = Intergroup relationships/integration, V24 = Marriage/Family, V25 = Solidarity, trust, cooperation, peace, respect, V26 = Love, V28 = Forced marriages, V29 = Gender equality/women's rights, V30 = Extremism/Terror, V31 = Discrimination/Islamophobia, V33 = Gratefulness, V34 = Halal, V35 = Serving, V36 = Martyrs, V37 = Umma, V38 = Sacrifice, V39 = Koranexegesis, V40 = Ramadan, V41 = 5 Pillars, V42 = Sins/Haram, V43 = Paradise, afterlife, V44 = Mercy.

Homeland-related sermons correlate significantly and positively with other topics, in particular democracy, extremism/terror, martyrs and negatively with sins/haram. The probability of homeland-related sermons occurring is highest between 2015 and 2016 compared to 2011, as well as 2019 (Figure 4). Interestingly, this coincides with time trends in nationalist references found in Diyanet sermons in Turkey (Ongur Reference Ongur2020).

Figure 4. Homeland-related sermons over time.

This raises the question of whether references to the homeland are related to the social situation in Turkey. However, there is no systematic relationship. Fragilization, which peaked in 2018, is not reflected in the data or a higher probability of references to the homeland in 2018. Accordingly, other reasons must be responsible for the significant increase in 2015 and 2016. Two types of events took place in Turkey during these years: terrorist attacks and a military coup (2016). These are mentioned, among other things, in the sermons. In the next step, a more detailed analysis of the content is presented.

Qualitative content analysis

Overall, we observed that “homeland” is constructed in five types of contexts: first, explicit mentioning and the use of words such as “we Turks” or “homeland” as is visible in this sermon:

May our God, Allah, accept our sacrifices. May this ritual serve as an opportunity to strengthen our feelings of unity, community and fraternity and lead to peace and security in our homeland and the Islamic world, and indeed in the whole world (DİTİB 2015a).

This quote explicitly uses the term “homeland” and puts it first, followed by the Islamic world and the rest of the world. This creates a hierarchy and demarcation between Turks and non-Turks on the one hand and Muslims and non-Muslims on the other. The prayer for peace, however, includes other parts outside of the homeland and the Islamic world. This is a good example of the ambivalence of the DİTİB, which tries to unite its own community and country of origin with the rest of the world, while at the same time reproducing identity categories.

The second quote does not introduce any hierarchy. It reminds the community of the history of migration, the emigration initially planned to be temporary, and the emotions associated with the homeland. This illustrates that Turkey continues to be the homeland even when living abroad. Interestingly, in this sermon, it becomes clear that Turkey is depicted as the home of subsequent generations. Linked to this is the expectation that they will bring good fortune to “their country”.

The main goal of everyone's emigration was to work for a few years in order to be able to afford a tractor, a house or a field and then to return home. But that didn't happen. However, even if most of them had to stay in the countries to which they had emigrated, they have never given up their—Allah-given—natural love for their homeland. After all, every human being feels a special love and interest for the place where they were born and raised, lived most of their life, experienced most of their memories, shaped history and culture, and where ancestors and relatives live. If a human being moves away from this place, it will miss it and will want to return there. […] On this occasion we would like to thank our elders who have created these opportunities for subsequent generations by wishing the deceased the mercy of Allah and the living health and well-being, with the hope that the following generations will bring good to their people (DİTİB 2018).

This highlights two roles of the DİTİB: on the one hand, the identity-creating role and, on the other hand, the normative role in the socialization of subsequent generations who are encouraged to show solidarity with their country of origin. With terms like “miss” or “every person feels a special love”, the emotional dimension of a home is created. This fits with the DİTİB's function, emphasized by Öcal (Reference Öcal2020), according to which the mosque should convey the feeling of home. In addition to fulfilling the needs of the community, expectations are raised in sermons, such in terms of bringing good to the people (the term Volk is used in the original version and means “people” or “nation’), remembering the history of the homeland, and paying respect to martyrs by visiting their graves in the homeland. The next sermon constructs a group membership, in addition to the use of the term “home”, linguistically through the use of phrases such as “our martyrs”—we will discuss the role of the martyrs again later.

Dear Muslims, you, my siblings, who have traveled thousands of kilometers to your countries of origin, in order to satisfy your longing for relatives, friends and homeland. I would like to remind you that, on the way to the homeland, and also while in the homeland, people who have influenced history and who have illuminated the paths of mankind, as well as our martyrs and their achievements, are awaiting our visit. If possible, visiting them at their graves is also an important task and responsibility of ours (DİTİB 2014c).

This quote demonstrates the relevance of remembering Turkish history and therefore builds a good bridge to the second type of context in which “homeland” is constructed. It establishes references to the homeland by using the emotionally less connoted term “country of origin”. Here, references are made to (current) events (e.g., terrorist attacks, the war in Syria, the last military coup), as the following sermon illustrates:

While we basked in the joyful glow of the time of pilgrimage and while Eid al-Adha was taking place, we, as a people, experienced a reprehensible terrorist attack in our country of origin, Turkey, which saddened us all very much. […]. At the end of my prayer, I would like to express my sincere condolences to all of our people and to all the mothers, fathers and relatives who lost their children in the deplorable terrorist attack in Ankara that targeted the whole population (DİTİB 2015b).

Another significant event in the history of Turkey concerns the military coup of July 15, 2016. The following quote combines several elements that have appeared in previous quotes. In addition to the historical event, there are also identity-creating terms such as “love for the homeland” and “our people”.

Love and sympathy for the homeland and the people is also part of these values. […] For this reason, in our religion, the love for one's homeland is regarded as part of our faith. Dear Believers! Just as there are individual tests for humans, entire populations also have tests. We, as a people, have been tested in almost every era of history. […] On the night of July 15, 2016, our people experienced a serious test. We witnessed an attempted coup against the independence of our people and the democracy of our country by internal and external evils and an unholy structure. The behavior of this junta—that has been running amok—towards their own people will certainly not be forgotten by the people and those involved in this terrible attempt will always be condemned. Thank God, with the help of our great God, Allah, the prudence and foresight of our people, the sincere supplications and intercessions of the oppressed and disadvantaged people, according to the statements in the Koran, we have been able to consolidate our brotherhood and unity and escape from the ring of fire, into which we, as a people, were pushed. With this, our noble people have again affirmed, to the whole world, their belief and loyalty to the rule of law and universal and democratic values. But through this event, it became visible that those who sowed the grains of sedition, insurrection and enmity for forty years have caused harm to our people. […] Seeing this, we should assess our environment correctly, and learn and practice our religion correctly, so that certain groups do not deceive us as well as our families and children and that they do not instrumentalize God and thus lead to confusion and turmoil (DİTİB 2016).

The author goes one step further and creates a direct connection between religion and love for the homeland: loving the homeland is part of the religion. This idea was expressed more indirectly in previous quotes, where it was said, for example, that the love for the homeland is given by Allah (DİTİB 2018). There is thus a direct link between religion and love for one's homeland, but also between religion and politics, and this is made clear in the plea to learn religion correctly in order to ensure that subsequent generations/children are not instrumentalized for such events. While overall rarely mentioned (Figure 3), the terms “democracy” and “democratic values” are mentioned several times in this sermon—they were undermined by the coup and illustrate a symbiosis of politics and religion. The sermon provides the community with an assessment of the situation: The people involved in the coup were referred to as evil and “a junta that has been running amok”. Moreover, they are described as both “internal” and “external” evils, suggesting that they are located within Turkey as well as abroad. These themes were prevalent in Turkish media sources, given that Fethullah Gülen, who lives abroad, was suspected as having been responsible for the coup (e.g., Zeit 2016; Deutsche Welle 2018).

In the next quote, the term “fatherland” is used instead of “homeland”. This sermon clarifies the strikingly frequent link between martyrdom and sermons that deal thematically with the homeland. The martyr's death secures entry into paradise and has a high value, as they stood up for the religion when it was seen as threatened. Religion and Turkey are closely intertwined here as martyrs died for their religion and their country:

Whenever religion, country, dignity and independence have been in danger, we have stood up for these values with our lives and will continue to do so in the future… Our ancestors fulfilled their duty in this sense. Some of them have died a martyr's death and have achieved this high rank. Others were wounded and returned as veterans. We owe to them the heroic epics about the martyrdom of the fallen. None of them are with us today. But one thing is still with us: our religion, our country for which they have paid with their blood, and our values. Maybe we are now living in a different country, in a different culture. But we have obligations that we have to meet. Above all, we should always embrace our ancestors in gratitude in our sermons, we should be rightly proud to inherit from them and walk with our heads held high. We should teach our children and grandchildren to love the fatherland. Our religion, our language, our culture and the values that are sacred to us, we must therefore live and let live by all of these values. As long as we stick together and do not allow unity and peace to be destroyed in the country, there is no goal that we cannot achieve, no problem that we cannot overcome (DİTİB 2014a).

In this sermon, believers are invited to preserve their religion and to stand up for their values if the religion is in danger again in the future, just as the martyrs did in the past. Religion comes first before maintaining language, culture and values. A recurring motif emerges here; the involvement of the next generation, whose bond with the “fatherland” needs to be strengthened. A second recurring motif in the discussion about home is the obligation to honor the ancestors/martyrs/history. Words such as “pride” and “love” are associated with the heroes of the nation and the fatherland.

The third form in which connections to the homeland are contextualized takes place through interpreting emigration in the historical context of the Koran. This makes clear that creating a new home as well as the reproduction of religious structures can be found again and again in the history of Muslims, in particular during the emigration of Muhammad in 622 from Mecca to Medina (Hijra) and thus refers to the community abroad:

But this emigration is not just about finding a new place to live and a new homeland. It's always about striving for that which is better and more beautiful and living Islam even more honestly. With emigration, we call such a journey “Hijra”. As the prophet Abraham said, we are all on our way to our God. We are all on the way from here to the eternal hereafter, the true world. This emigration means, as our beloved Prophet (s.a.w./p.b.u.h) put it, turning away from what Allah has forbidden. May good come to those who emigrate! May good come to those who carry the spirit of emigration (DİTİB 2017)!

The term homeland is primarily associated with Turkey, but terms such as “new homeland” or “second homeland” are used for Germany, as the quote below shows, which also provides an example for the fourth context:

We have chosen Germany as our second homeland in the truest sense of the word. During this time, we built over two thousand mosques. In a foreign land, the mosques literally became our home (DİTİB 2014b).

Germany is also mentioned in relation to intergroup relations/integration. There are very few sermons in which both homeland and intergroup relationships are discussed at the same time. In the sermon “Die erste Generation in Europa und die Treue zum Versprechen [The first generation in Europe and the loyalty to the promise]” (DİTİB 2018), love for the homeland, here in relation to Turkey, is addressed as well as coexistence with other religions and the integration efforts on the part of the guest worker generation in Europe.

Even if most of them have had to stay in the countries to which they emigrated, they have never given up—based on the Allah-given natural love for their country—their love for their homeland. […] Exactly as is the case today, Muslims in the past lived at peace with members of other religions in one place and produced many good role models for this coexistence. The first generation that emigrated to Europe worked day and night for the following generations by setting up—often without having the necessary language skills—associations and foundations and mosques. They found their place in the economy by starting their own companies. By enabling their children to enjoy a good education, they have succeeded in getting their children involved in areas such as education and health and politics (DİTİB 2018).

The isomorphic strategy, which would predict the simultaneous occurrence of references to the homeland, Turkey, alongside integration issues, can therefore be observed across all sermons, but rarely or not at all within the same sermon.

In addition to the isomorphic strategy, existing literature suggests direct links between the DİTİB and the Diyanet. This forms the fifth and final context. Sermons in which the Diyanet or the Directorate of Religious Affairs are mentioned are about requests for donations, but also about the training of imams, which is advertised in communities outside Turkey. For example, people who have graduated from high school can receive a scholarship in Turkey to learn Islam properly from trustworthy sources, and can transmit this knowledge and thereby become leaders for their community.

Yes, in addition to reaching out a helping hand to the oppressed and disadvantaged, the directorate also attaches great importance to educating fellow human beings and Muslim societies abroad so that they receive religious university education from trustworthy sources. Dear brothers and sisters! As part of the “International Theology Program (UIP)” that the directorate has developed, it has enabled university training in theological faculties since 2006. Starting in the countries in Europe and on to America to Australia, high school graduates who have completed the upper secondary level in their respective countries can benefit from this opportunity and enjoy their university education. In our view, besides local languages and culture, the scientific experience of graduates of the international theology program will be guiding lights for Islamic theology for our community in the respective countries […]. This important opportunity for Muslims living outside Turkey fills an important gap both for the correct understanding and transmission of Islam as well as for meeting the needs of believers in the religious field (DİTİB 2015c).

Homeland, as such, is not brought to the foreground here in comparison to most other sermons. It also mentions Turkey only in a very indirect way, in the everyday life of the DİTİB members living in Germany. By contrast, the relevance of the Diyanet for the community outside Turkey is always highlighted, for example by the fact that scholarship holders can return to their original communities after their training as an imam in Turkey, or by how much money has been raised in the community through donations. By outlining the benefits of the Diyanet's role in religious services to the German-Turkish community, the organization can legitimize itself.

Conclusion

As the literature suggests, the DİTİB is positioned between different actors, Turkey or the Diyanet, Germany, and the Turkish community there. Empirically, the variety of topics illustrates this: sermons that cover the topics of integration and discrimination are included as well as sermons that try to establish links with Turkey. In the foreground of the sermons are theological questions that cover the main concerns of the DİTİB. However, they can overlap with other topics, such as “integration” or “homeland”.

Since the core interest of this article lies in connections to Turkey, a quantitative content analysis was combined with a more in-depth qualitative content analysis. Overall, homeland-related sermons make up a minority of all sermons. Based on the analyses of the sermons only, homeland politics, or political issues in general, and religion do not seem to be as strongly linked in sermons as political issues and religion in Christian sermons in the US (Boussalis et al. Reference Boussalis, Coan and Holman2021). However, in order to fully grasp the relationship between religion and politics, an ethnography of the mosques and how the sermons are discussed in the mosque—formally and informally—would be useful. Islam in Germany is more strongly monitored, which might limit the interlinking between religion and political issues. However, we see a temporal variation in the occurrence of these. These sermons occur most frequently in the years 2015–2016. A closer look reveals that these 2 years overlap with terrorist attacks and the military coup in Turkey also discussed in the sermons, which does suggest that politics and religion are, to some extent, intertwined in the sermons. Hence, in a way, it can be observed that a destabilized political and social situation goes hand in hand with more references to the homeland. However, the time trend is not in line with the Fragile State Index. Neither is the instrumentalization of mosques for electoral purposes nor Erdogan's election victories or constitutional referendum in 2017 reflected in the sermons. One explanation for the deviation between the Fragile State Index and the references to the homeland could be that the index measures a wide range of dimensions, with not all being directly relevant. Yet, the time trends resemble the trends found when analyzing the Diyanet sermons in Turkey (Ongur Reference Ongur2020; Yilmaz and Barry Reference Yilmaz and Barry2020), which suggests that the content of sermons might be influenced by the Diyanet despite being written in Germany. Gorzewski (Reference Gorzewski2015, 274) outlines that the DİTİB has repeatedly used texts written by Diyanet officials in Ankara for German mosques over the past decade, despite the establishment of a local committee in Germany that drafts or adapts Diyanet texts.

The connection to the homeland, which primarily means Turkey, is discussed in five contexts. On the one hand, there are sermons that are directly related to emigrants and their descendants, with the aim of cultivating religion and culture, as well as venerating the martyrs who serve as role models. Here, the DİTİB takes on the role of an identity-creating agent of socialization. Second, the memory of the homeland is also kept alive in times when Turkey is exposed to political instability, as mentioned above, for example during the terrorist attacks and the coup. The third context, in which the concept of homeland is thematized, uses the history of Muslims as a reference point and reminds the community that emigration repeatedly played a role in the Koran and that the cultivation of religion is also important abroad. This brings us back to the starting point that the DİTİB appears here as an agent of socialization that creates identities and transmits the norms of the community.

As homeland is primarily linked to Turkey, only a few sermons link the concept of home to Germany and it is referred to as the “new” or “second” homeland. This constitutes the fourth type of context in which “homeland” is conceptualized. It mirrors existing data on the identification of the population of Turkish origin in Germany, who mostly identify with Turkey but not with Germany. At the same time, survey data repeatedly shows that religious identity is strong. The dynamics of individual identities and the contents of the Friday sermons should be investigated further, for example, in terms of whether the sermons are responding to the need of the immigrants to feel at home. Based on interviews with DİTİB representatives, Öcal (Reference Öcal2020) describes how what the organization offers has adapted to the needs of the Turkish community, providing shelter from exclusion. A qualitative study of mosque visitors, which also takes into account social processes or a possible reaction to the experiences of exclusion, could provide promising insights. Alternatively, it is also possible that it is a two-way process in which the sermons have a reinforcing effect on Turkish identity. Future research needs to unravel the reception and understanding of these sermons from the point of view of generation and education, given the relatively abstract language. Moreover, the reach of these sermons, meaning to what extent mosques belonging to the DİTİB adopt these sermons, constitutes a gap in the literature.

There is a fifth context in which references to Turkey are made—the relevance of the Diyanet for the community abroad is discussed. This is done by promoting training as an imam in Turkey in order to later return to their communities, as well as by outlining the function of the Diyanet for fundraising. This highlights how Turkey and the DİTİB are interlinked. Bruce (Reference Bruce2020) as well as Öztürk and Sözeri (Reference Öztürk and Sözeri2018) have argued that the Diyanet's training of imams aims at a continuation of the Diyanet's influence on communities abroad.

In order to locate the DİTİB in the area between Germany and Turkey, one can conclude that the interests of Turkey are weaved in by using identity-creating elements, references to Turkish history and current events, as well as the Diyanet, in the sermons. The topic of “migration” and the associated challenges such as discrimination and intergroup relationships are repeatedly discussed in sermons and this addresses the Turkish community abroad. Germany gains more attention when it comes to these topics.

It will be of great interest for future research to examine how the content will change if imams trained in Germany get more involved and religious structures become more rooted in Germany. Our findings bear relevance for other countries that host a significant Turkish population and/or have outsourced the organization of religion to the home countries of the immigrants. Existing literature and the sermons indicate an ongoing link between Turkey and the DİTİB. Thus, the DİTİB's independence from Turkey and European Islam still faces major hurdles (Arkilic Reference Arkilic2015). In the sermons, the topic of discrimination is raised simultaneously with extremism, which underlines the importance of integration. Hence, our results have implications for the integration of religious minorities, state-religion relationships and international relations, and they suggest that more support from governments in the countries of residence might help to strengthen the DİTİB's roots in the Western hemisphere with a view to preventing exclusion.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ruud Koopmans and Hilal Alkan for inspiring comments on a previous draft of the manuscript, and Kasimir Dederichs for help with the data preparation.

Conflict of Interest

No potential competing interest was reported by the authors.

Appendix

Table A1. Authors of sermons

Sarah Carol is assistant professor in sociology at the University College Dublin. She investigates immigrant integration in Western Europe and the role of religion. Her work has been published in Social Forces, International Migration Review, Sociology of Religion and many other journals.

Lukas Hofheinz is an alumnus of the University of Cologne.