The notion that ‘genius’ and ‘madness’ are closely related can be found in the writings of Aristotle, Plato and Socrates, Reference Hershman and Lieb1 and is a strongly held belief in literature, the arts and popular psychology. Reference Duke and Hochman2–Reference Horrobin6 The scientific evidence for such an association, however, is weak and inconsistent. Numerous historical studies of famous and creative individuals have found high rates of probable bipolar disorder, Reference Jamison7–Reference Post9 but such evidence relies on retrospective assessments of ability and psychopathology based on secondary sources, Reference Poole10 and is highly prone to selection bias. A few research studies have attempted to test the association using contemporaneous data, Reference Andreasen11 but investigators have faced two problems. The first is the inconsistent and subjective way in which high IQ or achievement is defined and quantified. The second is that ‘genius’, however defined, is rare, as is severe mental illness, so it is usually only possible to perform small case–control designs on highly selected samples. In their standard textbook on bipolar disorder, Goodwin & Jamison devoted a chapter to the relationship between human accomplishment and bipolar disorder. Reference Goodwin and Jamison12 They concluded that, despite anecdotal and biographical evidence suggesting a link, there is an urgent need for truly systematic, population-based studies. Reference Goodwin and Jamison12 In this cohort study, we used longitudinal data from over 900 000 individuals in Sweden to examine the relationship between scholastic achievement at age 16 and risk for affective psychosis in adulthood, controlling for potential confounders including socioeconomic group and parental education.

Method

We conducted a population-based historical cohort study with educational attainment at age 16 as the exposure and hospital admission for bipolar disorder as the outcome. The cohort was established on the basis of data obtained from seven Swedish national registers. The study was approved by local human ethics committees at the Karolinska Institutet (Stockholm, Sweden) and King's College London (Institute of Psychiatry).

Swedish national school register

The Swedish national school register, established in 1988, contains the individual school grades for all pupils graduating from compulsory education (class nine). The quality of the data in the National School Register is high and summary statistics are published regularly (www.skolverket.se). Under the Swedish educational system, most pupils with intellectual disabilities or sensory impairments are integrated into mainstream education and are thus included in the register. Independent schools, which provided only around 1% of compulsory education in Sweden before 1992, were included in the register from 1993 onwards.

All children in Sweden are obliged to attend school until June of the calendar year during which they turn 16, when they sit national examinations to assess their eligibility for upper secondary education (16–18 years). Pupils received grades ranging from ‘A’ (excellent) to ‘E’, in each of 16 compulsory subjects. The Swedish authorities used a standardised grading system, which was designed to follow a normal distribution, such that pupils in the top 7% of the population would receive A grades, those in the next 24% B grades, the middle 38% C grades, the next 24% D grades and the bottom 7% E grades. All children throughout Sweden took identical tests in Swedish and Mathematics. For other school subjects, schools could set their own tests, but the results were standardised nationally, as follows. The Swedish and Mathematics tests were used to compare the performance of each class within the country, which determined the proportion of grades at each level (A–E) that could be awarded in each class for the other subjects. Thus, the teacher of a class that had performed above average compared with the rest of Sweden would be allowed to award more A and B grades, and fewer D and E grades, than the teacher of an average class. The teachers then allocated the available grades in each of the other school subjects, based on the pupil's performance in the school examinations. Finally, the grades in all subjects were combined by the Swedish authorities, to calculate a grade-point average for each pupil. Pupils had a strong incentive to perform well since those with high grade-point averages were more likely to gain admission to the most desirable upper secondary schools. Reference Björklund, Lindahl and Sund13

Swedish hospital discharge register

The Swedish hospital discharge register contains details of virtually all psychiatric hospitalisations since 1973, including the discharge diagnosis made by the treating physician. It is coded using the ICD–9 14 until 1996 and ICD–10 15 subsequently.

Additional registers

The death and emigration register includes the dates of all deaths or emigrations from Sweden, and allowed us to take into account censoring of follow-up data. The multigeneration register enabled us to identify the parents of the children, allowing linkage to the education, census and population registers, which includes information on the parents' socioeconomic status, education level, country of origin and citizenship.

Analytic cohort

The study population comprised all individuals in the national school register from 1988 through to 1997 inclusive (n = 907 011). To prevent confounding by migrant status, and to minimise missing data, we excluded individuals if one or both parents were born outside Sweden (n = 181 596). To minimise reverse causality (the effects of incipient mental disorder on school performance), we excluded individuals who developed bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or any other psychotic disorder prior to the examinations, or in the year following their examinations (n = 375).

Individuals were censored if they developed another psychotic disorder (n = 1525), died (n = 235) or emigrated (n = 9404) during the follow-up period. The remaining 713 876 individuals were followed to 31 December 2003. The mean follow-up time was 9.48 years, giving 6 783 520 person-years at risk, with a mean age of 26.48 years at the end of follow-up.

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed using Intercooled STATA for Mac OS X version 10.1. To allow scale-independent comparisons with other studies, we converted grade-point averages to z-scores (standard deviations from the gender-specific population mean). We defined four exposure categories: z-score >+2, +1 to +2, −1 to −2 and < −2, with z-score −1 to +1 as the reference category. Using Cox proportional hazards models, we calculated hazard ratios for hospital admission for bipolar disorder, with z-score as the exposure. We censored observations at the date of death, emigration or admission for non-affective psychosis or 31 December 2003, whichever occurred first. We confirmed that the data satisfied the proportional-hazards assumption using Schoenfeld residuals. Reference Schoenfeld16

We ran crude and adjusted models, the latter controlling for gender, advanced paternal or maternal age (the cut-off was 40 years), highest parental socioeconomic status at either census (1980 or 1990), highest parental education and winter/spring birth (January to April).

In a post hoc analysis, we explored whether high performance in particular school subjects was associated with risk of bipolar disorder, by investigating the grade A in each school subject as risk factors for bipolar disorder.

Results

There were 280 individuals with bipolar disorder (ICD–9 codes (Swedish version) 296, 296.A, C–E, W, X; ICD–10 codes F300–319), with a mean age at onset of 20.79 years (s.d. = 2.73, range 16.73–29.14). The mean number of admissions was 2.50 (s.d. = 2.65, median 2). The incidence of bipolar disorder was 4 per 100 000 person-years, identical to the rate in a recent large UK study of bipolar disorder. Reference Lloyd, Kennedy, Fearon, Kirkbride, Mallett and Leff17

Grade-point average scores for the population followed a normal distribution, and ranged from 1.0 to 5.0 for both genders, with means of 3.11 (s.d. = 0.69) for males and 3.39 (s.d. = 0.66) for females. A total of 2833 individuals (0.3% of the sample), including 2 with bipolar disorder, had a missing grade-point average, and were excluded from subsequent analyses (hazard ratio (HR) for missing grade compared with non-missing 2.03 (95% CI 0.51–8.16, χ2 = 1.04, P = 0.31)). In the sample, 1602 students repeated their last year of secondary education, 1 of whom developed bipolar disorder (HR for repeated year compared with no repeated years 4.71 (95% CI 0.66–33.51, χ2 = 2.9, P = 0.09)).

Table 1 gives the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. Individuals with bipolar disorder were more likely to have an older father and better educated parents. There was a small excess of females with bipolar disorder.

Table 1 Sample characteristics

| Population | Bipolar disorder | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n (%) | n (%) | Incidence rate per 100 000 person-years | 95% CI |

| Total sample | 713 596 | 280 | 4.10 | 3.64-4.61 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 364 839 (51.0) | 128 (45.7) | 3.71 | 3.12-4.40 |

| Female | 348 757 (49.0) | 152 (54.3) | 4.51 | 3.84-5.30 |

| Parent over 40 years at birth | ||||

| Father | 25 837 (3.6) | 15 (5.4) | 6.09 | 3.67-10.11 |

| Mother | 3 684 (0.5) | 1 (0.4) | 2.89 | 0.41-20.48 |

| Season of birth: January to April | 249 518 (34.8) | 112 (40.0) | 4.54 | 3.78-5.47 |

| Highest parental socioeconomic groupa | ||||

| Self-employed/company owner | 60 024 (8.4) | 25 (8.9) | 4.37 | 2.95-6.46 |

| White collar higher | 108 933 (15.3) | 41 (14.6) | 4.00 | 2.95-5.43 |

| White collar middle | 92 678 (13.0) | 26 (9.3) | 2.96 | 2.02-4.35 |

| White collar lower | 168 694 (23.6) | 74 (26.4) | 4.56 | 3.63-5.74 |

| Blue collar higher | 153 708 (21.5) | 74 (26.4) | 5.01 | 3.98-6.30 |

| Blue collar lower | 125 147 (17.5) | 36 (12.9) | 2.98 | 2.15-4.13 |

| Missing | 4 412 (0.6) | 4 (1.4) | 9.51 | 3.57-25.34 |

| Highest parental educationa | ||||

| Higher education ≥3 years | 166 757 (23.4) | 89 (31.8) | 5.68 | 4.61-7.00 |

| Higher education <3 years | 117 984 (16.5) | 46 (16.4) | 4.10 | 3.06-5.49 |

| High school 3 years | 110 147 (15.4) | 39 (13.9) | 3.71 | 2.71-5.08 |

| High school 2 years | 238 593 (33.4) | 78 (28.0) | 3.42 | 2.74-4.27 |

| Compulsory school only | 76 644 (10.7) | 25 (8.9) | 3.24 | 2.19-4.79 |

| Missing | 3 471 (0.5) | 3 (1.1) | 8.68 | 2.80-26.92 |

There was a non-significant linear association between grade-point average and risk for bipolar disorder (HR for one point increase 1.16, 95% CI 0.98–1.39). The addition of a quadratic term greatly improved the fit (likelihood ratio test χ2(1 d.f.) = 15.72, P<0.001), suggesting a non-linear association between school performance and risk of bipolar.

Table 2 shows the association between school performance and risk of bipolar disorder by z-score category. Individuals at both the low and high ends of the school grades distribution had a significantly higher risk for bipolar disorder. Those in the highest grade category, with grades of two or more standard deviations above the mean, were nearly four times more likely to develop bipolar disorder than those with average scores, whereas those in the lowest grade category were around twice as likely.

Table 2 Z-score of grade-point average as a risk factor for bipolar disorder

| Standardised grade category | Population n (%) | Bipolar disorder n (%) | Incidence per 100 000 person-years (95% CI) | Crude hazard ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted hazard ratioa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < -2 | 20 517 (2.9) | 13 (4.7) | 6.68 (3.88-11.50) | 1.86 (1.06-3.28) | 1.96 (1.07-3.56) |

| -2 to -1 | 104 707 (14.7) | 37 (13.4) | 3.69 (2.67-5.09) | 1.03 (0.72-1.47) | 1.16 (0.81-1.68) |

| -1 to +1 | 461 628 (64.8) | 160 (57.2) | 3.60 (3.08-4.21) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| +1 to +2 | 115 981 (16.3) | 56 (20.3) | 5.16 (3.97-6.70) | 1.42 (1.05-1.93) | 1.24 (0.90-1.71) |

| >+2 | 9 427 (1.3) | 12 (4.3) | 13.83 (7.85-24.35) | 3.79 (2.11-6.82) | 3.34 (1.82-6.11) |

The association was slightly attenuated in the fully adjusted model, controlling for parental education, socioeconomic group and other potential confounders, but the associations with both high and low grades remained. The addition of confounders to the model had small, but opposite, effects on the associations between high and low scores and bipolar disorder. The association between high school performance and bipolar disorder was attenuated, suggesting that some confounding may have been present. However, the association between low school performance and bipolar disorder was accentuated, suggesting negative confounding (unmasking of a true effect). Further analyses (not shown) demonstrate that most of this pattern of positive and negative confounding was attributable to parental education. Thus, the association between high school performance and bipolar disorder may be partly confounded by high parental education, whereas the relationship between low school performance and bipolar disorder may have been masked by the fact that individuals with bipolar disorder had better-educated parents, which had ‘pulled up’ their scores.

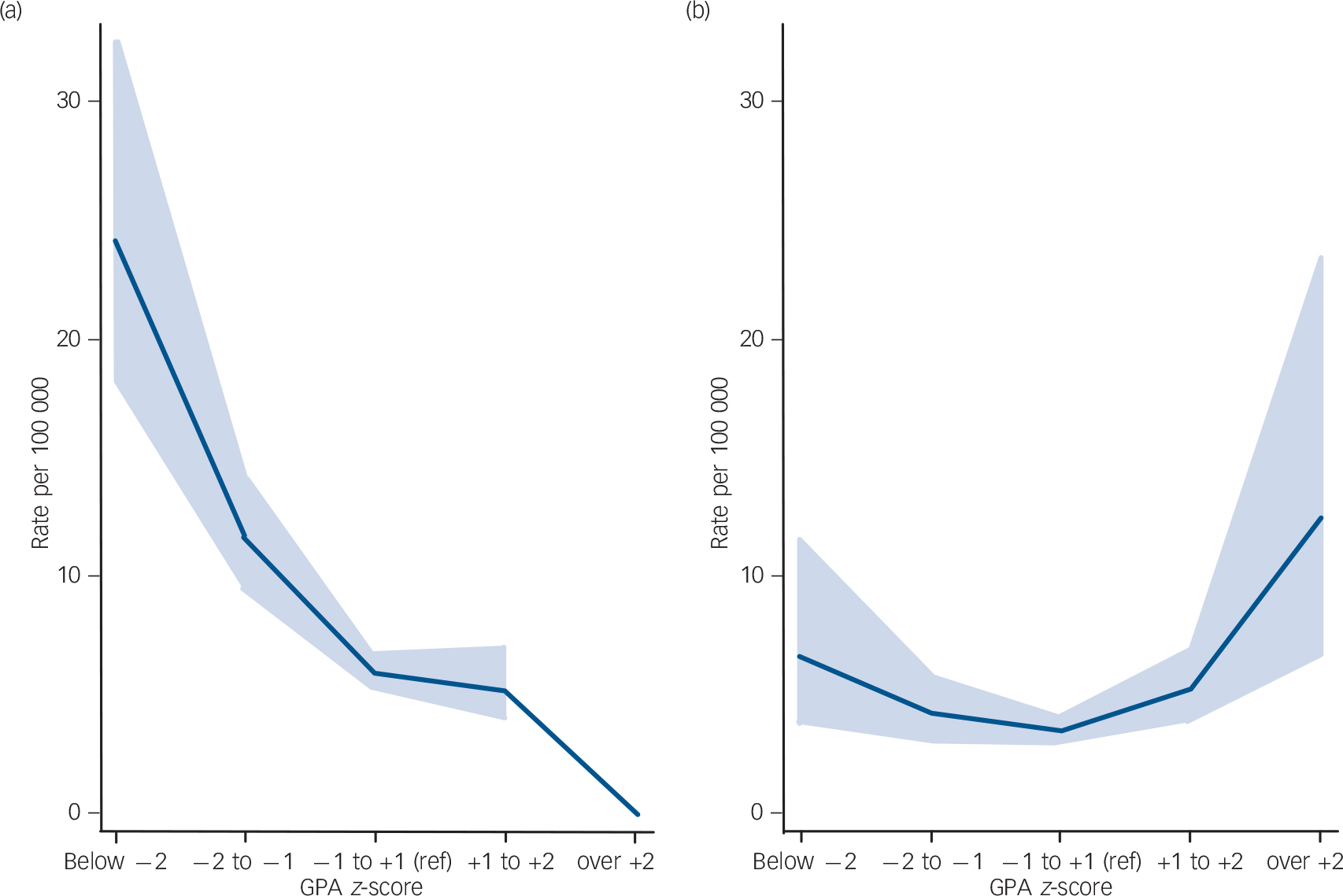

Figure 1 shows the incidence rate of bipolar disorder for individuals in each performance category of grade-point average. For comparison, incidence rates of schizophrenia in the same sample (reported separately in MacCabe et al) Reference MacCabe, Lambe, Cnattingius, Torrang, Bjork and Sham18 are shown alongside. The contrast with schizophrenia is most marked at higher levels of school achievement, which are associated with increased risk of bipolar disorder but decreased risk of schizophrenia.

Fig. 1 Incidence rate of (a) schizophrenia and (b) bipolar disorder by grade-point average. The 95% confidence intervals are indicated by the shaded areas.

Table 3 shows the association between overall school performance and bipolar disorder, by gender, fully adjusted. The association between high scholastic achievement and bipolar disorder appears to be stronger in males. However, the interaction between school performance and gender failed to reach statistical significance at the P = 0.05 level (likelihood ratio test comparing the fully adjusted model in Table 2 with a model including interaction terms for each school performance level with gender: χ2 (4 d.f.) 5.71, P = 0.222).

Table 3 Z-score of grade point average as a risk factor for bipolar disorder, fully adjusted, by gender

| Standardised grade category | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | |

| < -2 | 2.07 (0.88-4.87) | 1.84 (0.79-4.28) |

| -2 to -1 | 1.01 (0.57-1.76) | 1.32 (0.81-2.15) |

| -1 to +1 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| +1 to +2 | 1.06 (0.64-1.73) | 1.40 (0.92-2.14) |

| >+2 | 4.37 (2.25-8.48) | 0.86 (0.12-6.22) |

Table 4 shows the hazard ratio for bipolar disorder associated with achieving an A grade in each subject v. a B–D grade. For ease of interpretation, the school subjects are ranked by strength of association with bipolar disorder in the adjusted analysis. In general, all academic subjects, and some non-academic ones, have positive associations with bipolar disorder, such that scoring an A grade is associated with increased risk. Generally, A grades in the humanities are more strongly associated with bipolar disorder, whereas science and technical subjects are less strongly associated. Scoring an A grade in Sport appears to be protective against bipolar disorder.

Table 4 Risk of bipolar disorder for individuals scoring an A grade in each individual subject compared with a reference group of those scoring B–D, crude and fully adjusted

| Crude | Adjusteda | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P |

| Childcare | 2.18 (1.58-3.02) | <0.001 | 1.95 (1.39-2.75) | <0.001 |

| Swedish | 2.24 (1.59-3.15) | <0.001 | 1.92 (1.34-2.76) | <0.001 |

| Geography | 2.11 (1.52-2.95) | <0.001 | 1.88 (1.34-2.66) | <0.001 |

| Music | 2.05 (1.48-2.84) | <0.001 | 1.77 (1.26-2.49) | 0.001 |

| Religion | 2.00 (1.44-2.78) | <0.001 | 1.75 (1.25-2.47) | 0.001 |

| Biology | 2.12 (1.45-2.79) | <0.001 | 1.68 (1.19-2.37) | 0.003 |

| History | 1.83 (1.32-2.46) | <0.001 | 1.58 (1.12-2.23) | 0.009 |

| Engineering | 1.59 (0.96-2.63) | 0.073 | 1.47 (0.88-2.45) | 0.138 |

| Civics | 1.72 (1.22-2.43) | 0.002 | 1.46 (1.02-2.10) | 0.039 |

| Home economics | 1.68 (1.14-2.47) | 0.008 | 1.46 (0.98-2.17) | 0.064 |

| English | 1.60 (1.09-1.35) | 0.017 | 1.35 (0.90-2.01) | 0.145 |

| Chemistry | 1.52 (1.05-2.18) | 0.025 | 1.34 (0.92-1.95) | 0.128 |

| Mathematics | 1.44 (0.98-2.11) | 0.064 | 1.32 (0.89-1.95) | 0.169 |

| Art | 1.36 (0.92-2.02) | 0.119 | 1.16 (0.77-1.73) | 0.485 |

| Physics | 1.30 (0.89-1.91) | 0.181 | 1.11 (0.74-1.65) | 0.622 |

| Handicraft | 0.64 (0.36-1.15) | 0.133 | 0.58 (0.33-1.04) | 0.069 |

| Sport | 0.42 (0.24-0.75) | 0.003 | 0.40 (0.23-0.72) | 0.002 |

Discussion

Summary of findings

In this longitudinal cohort study of all school children completing compulsory schooling in Sweden between 1988 and 1997, poor and excellent school performance are both associated with increased risk of bipolar disorder compared with average performance. These associations are neither explained by differences in socioeconomic group nor parental education. In all academic school subjects, achieving an A grade is associated with increased risk for bipolar disorder, particularly in humanities and to a lesser extent in science subjects. The associations between high grades and bipolar disorder contrast markedly with those for schizophrenia in the same sample, where high grades appeared protective. Reference MacCabe, Lambe, Cnattingius, Torrang, Bjork and Sham18

Limitations

Validity

Although the Swedish authorities went to great lengths to peer-reference the school grades from different schools, it is unlikely that such standardisation was flawless. The diagnoses in this study were based on routinely collected clinical data, raising concerns of validity. Two studies have demonstrated good concurrent validity for diagnoses of schizophrenia in this register, Reference Dalman, Broms, Cullberg and Allebeck19,Reference Ekholm, Ekholm, Adolfsson, Vares, Osby and Sedvall20 but the validity of diagnoses of bipolar disorder is not known.

Bias

Some patients in Sweden are treated entirely outside hospital, but the registers only record patients admitted to hospital. Our study may therefore be biased towards more severe cases. However, such a bias would probably have attenuated our main finding, the association between excellent school performance and bipolar disorder.

A second possible bias is that individuals with higher IQ, or their families, may be more likely than others to seek treatment. However, if this were the case, one would also expect individuals with better school performance to have higher rates of admission for other psychiatric disorders, but our previous research has demonstrated the opposite association with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Reference MacCabe, Lambe, Cnattingius, Torrang, Bjork and Sham18 A third potential source of bias relates to the perception of an association between bipolar disorder and creativity or high IQ. It is plausible that psychiatrists may have been biased in their diagnostic practice, favouring a diagnosis of bipolar disorder in people who appeared to have higher IQ.

Confounding

Although we were able to adjust for many potential confounders, such as socioeconomic group, we did not have data on family history of bipolar disorder. Confounding by family history could have contributed to the association between low school performance and bipolar disorder, via emotional distress and disruption of schooling in the offspring of individuals with bipolar disorder.

Prodromal and subclinical symptoms

One of the main advantages of prospective study designs is that disease outcome cannot bias the measurement of the exposure, since the exposure is measured before the onset of the disorder. However, the age at onset of bipolar disorder is notoriously difficult to ascertain, and this study relied on the relatively crude indicator of hospital admission. It is possible that some individuals were suffering from prodromal or subclinical symptoms of hypomania or depression when they took their examinations and that this might have influenced their performance. In general, one might expect prodromal symptoms to impair performance, but given the observed association between excellent school performance and bipolar disorder, it is conceivable that students with prodromal symptoms of mania might actually perform better than average.

We tried to minimise this effect by excluding any children who had an admission prior to their examinations or in the first year after taking the examinations. To assess the extent of confounding by prodromal symptoms, we doubled this period of exclusion to 2 years and observed little change in our findings (HR for ‘>+2 s.d.’ = 3.04, 95% CI 1.49–6.21; HR for ‘>+2 s.d.’ = 2.05, 95% CI 1.14–3.72). Extending the exclusion period to a third year, however, resulted in excluding 91 individuals (nearly a third of the sample), with a consequent loss of power. Nevertheless, there is some evidence that the association with excellent performance was attenuated (HR for ‘>+2 s.d.’ = 1.35, 95% CI 0.43–4.28; HR for ‘>+2 s.d.’ = 2.25, 95% CI 1.21–4.18).

Comparison with previous findings

Previous cohort studies investigating premorbid cognitive function in bipolar disorder have shown either performance within the normal range, Reference Reichenberg, Weiser, Rabinowitz, Caspi, Schmeidler and Mark21,Reference Zammit, Allebeck, David, Dalman, Hemmingsson and Lundberg22 or deficits in specific domains such as visuospatial reasoning. Reference Tiihonen, Haukka, Henriksson, Cannon, Kieseppa and Laaksonen23

Some previous cohort studies have, however, provided tentative evidence of superior premorbid educational or cognitive performance in bipolar disorder. In a population-based Finnish study, Aro and colleagues found higher admission rates for bipolar disorder in people who had completed more than 12 years of education, particularly in males, whereas the reverse was true for other psychotic and affective disorders. Reference Aro, Aro, Salinto and Keskimaki24 In the Dunedin Cohort, Cannon and colleagues examined prospectively collected data on premorbid cognitive and neuromotor development in around 1000 children. Children who would develop mania in adulthood outperformed controls on motor performance, controlling for gender and socioeconomic status. Reference Cannon, Caspi, Moffitt, Harrington, Taylor and Murray25 Very recently, the same researchers showed that those children who went on to develop mania also had significantly higher IQs than the remainder of the cohort, but the authors acknowledged that the sample was small, with only eight children going on to develop mania, and they called for replications in a larger sample. Reference Koenen, Moffitt, Roberts, Martin, Kubzansky and Harrington26

Gender differences

The association between high scores and risk for bipolar disorder seems to be confined to males, although the formal test for interaction between school marks and gender was not statistically significant. Replication will be required before we can draw any firm conclusions as to whether the association is truly stronger in males. However, it is notable that the great majority of the eminent creative individuals with probable bipolar disorder described in the biographical studies of Jamison and others were male. Reference Hershman and Lieb1,Reference Jamison3,Reference Nettle5,Reference Jamison7,Reference Post9–Reference Andreasen11

School performance, IQ and creativity

The overlap between IQ and school performance has been the focus of extensive research, and studies typically show correlations of around 50%. In one of the largest such studies, involving 70 000 individuals in a longitudinal design, Deary and colleagues found that 50–60% of the variance in examination results at age 16 could be explained by IQ at age 11. Reference Deary, Strand, Smith and Fernandes27 This suggests that IQ is only one of several factors influencing success in school examinations. These may include school attendance and engagement, long-term memory, attention, motivation, diligence, organisational abilities, creativity and social skills. The associations with risk for bipolar disorder may be driven as much by these other factors as by IQ, and the associations with excellent and poor performance may each be mediated by different factors.

The overlap between creativity and academic performance is poorly understood. Of the compulsory school subjects taught in Sweden, Art, Music and Swedish (which includes creative writing) seem intuitively to be closest to the concept of creativity. It is therefore notable that A grades in Swedish and Music have particularly strong associations with risk for bipolar disorder. This provides support for the biographical literature, which consistently finds associations between linguistic Reference Jamison7,Reference Post9,Reference Andreasen11 and musical Reference Poole10 creativity and bipolar disorder.

Putative mechanisms

Bipolar disorder is associated with several cognitive styles that could also be related to creativity or scholastic achievement. First, people with hypomania have apparently enhanced access to vocabulary, memory and other cognitive resources, with successive ideas being linked in innovative ways, and individuals in this mental state can often be witty and inventive. Second, people with bipolar disorder often show exaggerated emotional responses, which may facilitate their talent in art, music and literature. Third, individuals with hypomania often have extraordinary stamina, and a tireless capacity for sustained concentration. Any or all of these cognitive styles or a predisposition to hypomanic mental states, may facilitate high levels of performance in creative school subjects, but also predispose to bipolar disorder. Indeed, it has been observed that the creative output of individuals with bipolar disorder frequently coincides with periods of hypomania. Reference Jamison3 The converse of this mechanism may explain the association between poor school performance and bipolar disorder; a proportion of individuals who go on to develop bipolar disorder, perhaps those with a predominance of depressive symptoms, may have particular cognitive styles that impair their academic functioning. It is also possible that disturbed behaviour, substance misuse or undiagnosed depression may have affected the performance of these individuals.

Unlike schizophrenia, bipolar disorder seems not to be associated with impaired fecundity, Reference MacCabe, Koupil and Leon28 and it has been suggested that selection pressure against bipolar-predisposing genetic variants may be counteracted by a selective advantage conferred through increased creativity or IQ. Reference Keller and Miller29 If particular cognitive styles or personality traits are the link between school performance and bipolar disorder, it is likely that they have a genetic basis. One putative locus is the val66met BDNF polymorphism, where the val allele is associated with bipolar disorder, Reference Farmer, Elkin and McGuffin30 and in people with bipolar disorders, it has associations with rapid cycling Reference Müller, de Luca, Sicard, King, Strauss and Kennedy31 and superior frontal lobe functioning. Reference Rybakowski, Borkowska, Skibinska and Hauser32 Another candidate is the SNP8NRG243177/ rs6994992; C v. T polymorphism of the promoter region of neuregulin 1, where the TT genotype, previously linked to risk for psychosis, was recently shown to be associated with creative thinking styles in people with high academic achievement. Reference Keri33

Relationship between bipolar disorder and schizophrenia

The contrast in the pattern of school results that predict schizophrenia and bipolar disorder is very striking: high grades are associated with increased risk for bipolar disorder but decreased risk for schizophrenia, whereas low scores are associated with increased risk for both disorders, particularly schizophrenia (Fig. 1). We have outlined a model elsewhere Reference Demjaha, MacCabe and Murray34 to account for the similarities and differences between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, whereby, on a background of some shared genetic liability for both disorders, schizophrenia is associated with additional genetic and environmental risk factors that impair neurodevelopment. The results from this study are broadly compatible with this proposal, although the observation that very poor scholastic achievement was also associated with risk for bipolar disorder does not fit this model.

One possible refinement to the model is that the clinical syndrome of bipolar disorder may include two distinct subgroups, one associated with high, and the other associated with low, scholastic achievement. Given that poor scholastic achievement was strongly associated with schizophrenia in the same sample, Reference MacCabe, Lambe, Cnattingius, Torrang, Bjork and Sham18 it may be that some individuals with bipolar disorder, perhaps particularly those with low scores on Sport and Handicraft, may have subtle neurodevelopmental abnormalities, similar to those in schizophrenia. By contrast, those individuals with bipolar disorder who have excellent school performance may have a different aetiology, which is linked to high IQ or creativity, and not associated with neurodevelopmental deviance.

Funding

J.H.M. was funded by a joint Department of Health/Medical Research Council Special Training Fellowship in Health of the Population Research (No. G106–1213). The Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (grant No. 2013/2002) supported the study.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Sven Sundin of the Swedish national education board for his advice on the interpretation of school records, Camilla Björk for managing the database, and Anna Torrång and Paul Dickman for statistical advice.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.