5 Tracing elite career networks

This chapter builds on the political backgrounds and varying contexts of uncertainty presented in Chapter 4. Through a macro-level analysis of the career networks of elite state officials, it provides an empirically grounded theory of the interplay of uncertainty and networks in institutional development.

Scholars have examined the impact of different forms of embeddedness in accounts of the state’s ability to govern the economy (Wade Reference Wade1990; Evans Reference Evans1995; Kang Reference Kang2002). This chapter, however, offers one of few studies that use data to understand the role of networks between state officials and the private sector. As the coming pages show, these cleverly forged relations are only partly shaped by the individual ambitions of bureaucrats. Political parties also view the deployment of party members to other sectors as a way of creating relational assets that are important in securing political finance for parties and creating lasting bonds with firms. These maneuvers, in combination with the level of political uncertainty, generate different elite networks. As in the case of ownership networks, over time Poland developed the broadest elite network, whereas Bulgaria’s and Romania’s networks were both much more narrowly connected.

How elite networks function

Across the post-socialist landscape, poorly paid bureaucratic positions are seen as a stepping stone for talented individuals on their way to the private sector. For example, the former head of the Bulgarian Parliamentary Energy Committee, Nikita Shervashidze, was influential in the signing of a controversial contract between the state gas monopoly Bulgargas and two companies owned by Multigroup, the company that has been described as a “state within the state” for its ability to evade official control (Ganev Reference Ganev2001). As a result of this contract, Multigroup’s companies performed financial services that involved transferring Bulgargas’s receivables from two other large state companies, Chimco and Kremikovtsi, to itself. Shevarshidze subsequently left his government post and founded the National Gas Company, affiliated with Multigroup, and initiated the establishment of the Energia Invest privatization fund, which has acquired assets in a number of companies from the power industry through mass privatization.

Some authors have suggested that the post-communist left was better placed and more skillful at creating such networks (Staniszkis Reference Staniszkis2000). This is not substantiated by the historical record, however: the Bulgarian Socialist Party’s conservative rival, the Union of Democratic Forces, also created a network through which it could control economic resources. Once the UDF gained control of the government in 1997, it began to introduce management–worker partnerships in a large number of Bulgarian state-owned companies as part of its privatization strategy. As part of this policy, the UDF managed to change the directorates of several companies and installed directors who were party allies or top members of the party. This move, according to the standard argument, was necessary to prevent the mismanagement of state-owned firms by former socialist managers. The main goal, however, was to remove firms from the political control of the Socialist party. Interviews with politicians of various parties reveal that this did not mean that the firms became depoliticized property; rather, in short order, firms were sold to the RMDs and became sources of UDF donations. The pressure to compete for economic resources with other parties meant that having politically connected managers in place was key to the activities of all political parties. Commenting on the view that these networks were a resource for parties even after the individuals left formally political postions, a politician observed, “The UDF elite is still here. And the BSP elite is still here. For example, after the UDF government a lot of the UDF people went into the high court, the constitutional court, the high police agencies. Some of them became businesspeople. So they didn’t disappear.”

Whereas Bulgarian parties struggled to retain control of economic assets, Polish firms established stable ties with political parties that included the exchange of elites. These ties were instrumental for both sides. For example, the former deputy minister of trade and industry, Kazimierz Adamczyk, became the president of EuRoPolgaz, a company that is a critical mediator and beneficiary of trade between Russia’s Gazprom and the Polish natural gas monopoly. Adamczyk also sat on the supervisory board of the Cigna STU insurance company. One of Adamczyk’s former colleagues made a career in the gas business: Roman Czerwinski, the president of PolGaz Telekom, a dependent company of Gazprom, used to be deputy minister of industry. When he was in government, Czerwinski was responsible for the power sector. As minister, he negotiated the contract of the Yamal gas pipeline with Gazprom, while PolGaz Telekom signed contracts on the construction and use of a fiber optic cable, which runs along the pipeline (Polish News Bulletin 2000).

Andrzej Śmietanko, a Polish Peasant Party activist, became minister of agriculture for the PSL government of Waldemar Pawlak and later an advisor to President Kwasniewski. On leaving government, he became the president of Brasco Inc., a company involved in natural gas and part of Gudzowaty’s empire. Śmietanko was a good investment for Gudzowaty because he was a strong opponent of Poland’s largest company and top fuels group, PKN Orlen, when it tried to prevent the passage of a law that would mandate the sale of biofuels in the Polish market. Gudzowaty, on the other hand, had already invested in several biofuel companies and needed Śmietanko’s contacts to push the law through parliament. The latter remains an important figure in the PSL.

These examples suggest that the politicization of property did not end with privatization but instead spread to the emerging private sector. In other words, private property could also be politicized property. All political parties sought to control property in search of advantages during the intense political struggles after 1989. The more intense party competition became, the more deeply this logic took hold.

Whereas the development of a network of loyal party supporters across the state, private, and non-profit sectors took place in every country, these networks took different forms across cases. I explore the mobility of individuals, what sectors they moved between, and, most importantly, the structure of the network of elites that developed as a result of these individual moves.

Poland had an abundance of figures with one foot in the state and one foot beyond, on either the left or the right side of the political spectrum. Elite state officials also experienced a high degree of job mobility during their careers. This supports the argument, made throughout this book, that Poland represents a key variety of post-socialist capitalism that is structured around dense ties in the partisan division of the economy.

Romania instead was a dominant-party regime for much of the first decade, and was dominated by state elites who emerged from a single national unity coalition after the violent and still murky revolution. Overall, Romania has been marked by very low mobility, much of it occasioned by the entrance of the first opposition government in 1996 and its exit in 2000, when many bureaucrats who had served from 1990 to 1996 returned to their state positions. This low mobility was concentrated within the state and was also apparent in the movement of some state officials to the parliament.

Bulgaria experienced the highest degree of mobility, with a high frequency of placements. The range of movement was limited, however, as it was concentrated in moves between private business and the key state ministries that regulate finance and the economy, industrial policy, internal security, and matters related to defense, including highly profitable firms producing arms for export. Such trajectories reflect the ability of business to dominate the state, but, because Bulgarian elites were concentrated in firms and these ministries, the range of career paths was limited and the overall effect was that the Bulgarian network was much less broad than the Polish network.

Networks of individuals

What is the role of persons and personnel networks in the exercise of state power? Do dense networks linking the state to the public sphere enhance state power or impede the exercise of government? By developing the concept of “state embeddedness,” Evans and others have argued that such networks can, under certain circumstances, enhance the state’s ability to make and implement policy by improving information flows and coordination (Gerlach Reference Gerlach1992; Evans Reference Evans1995; Kang Reference Kang2002). On the other hand, some have argued that networks constrain the state’s ability to build institutions and develop autonomy from powerful interests (Jowitt Reference Jowitt1983; Ledeneva Reference Ledeneva1998; Ganev Reference Ganev2007), although these arguments do not explicitly discuss the structure of networks.

As sets of ties that link two or more organizations in a structure that is not just hierarchical, networks connect actors in public administration to other actors in the same ministry or agency, other levels of government, other ministries, and outside the state to private and non-profit actors. Networks can be used to mobilize actors, acquire and share information, generate support, and move a set of actors toward an objective or goal (O’Toole Reference O’Toole2010: 8). Networks related to public administration link actors through three basic kinds of ties – authority, common interest, and exchange (O’Toole and Montjoy Reference O’Toole and Montjoy1984, cited by O’Toole Reference O’Toole2010: 8) – and act as both capacity enhancers and constraints on action by raising the number of potential veto points (Simon Reference Simon1964, cited by O’Toole Reference O’Toole2010: 8). Thus, it is important to distinguish between different types of network structures in order to determine what a particular network can do best. Above all, narrow networks perform different functions from the ones that broad networks do (Scholz, Berardo, and Kile Reference Scholz, Berardo and Kile2008). The former assist in the generation of credible commitments that support cooperation among a small set of actors, while the latter reduce search costs when these pose the greatest obstacle to collaboration. Thus, broad networks between public administration and non-state actors can assist with the conduct of policy by allowing affected groups to communicate concerns to policy makers, receive information about upcoming policy shifts, and generate coalitions of support or opposition by bringing together distant actors around credible commitments to collective action. Narrow networks do not perform these functions (O’Toole and Montjoy Reference O’Toole and Montjoy1984; O’Toole Reference O’Toole1997; Lazer and Friedman Reference Lazer and Friedman2007; Feiock and Scholz Reference Feiock and Scholz2009).

This view is in line with the argument made in this book, with the difference that I consider cases in which the institutional context is incomplete. In the absence of strong institutional constraints, networks matter even more in shaping and determining the types of policies that are chosen. Broad networks reduce search costs, spread information, and mobilize cooperation. The constraint-raising quality identified by Simon (Reference Simon1964) is what leads broad networks to support collective action, as large sets of actors are able to veto narrowly distributive outcomes. This is the dynamic at work in Poland. Narrow networks can support cooperation among small sets of actors and favor narrowly distributive outcomes; this describes the situation in both Bulgaria and Romania. Building on previous chapters, however, the argument developed in the coming pages is that the presence of broader networks is not of itself sufficient to determine whether powerful societal interests collaborate to support the process of institutional development or to subvert it. Instead, network features must be examined together with uncertainty in order to determine how the path of institutional development unfolds.

This chapter considers the uncertainty of career paths that derive from political dynamics, and therefore it focuses on the extent to which job changes coincide with elections. The meaning of a job change is very different if one changes jobs for a better position by choice or if that change is involuntary, prompted by a political dismissal after an election. Frequent election-related job changes suggest the broad politicization of key jobs in a society but also imply that politics serves as an effective check against the prolonged use of powers connected to a particular position by a single individual. The less individuals change jobs over time, the more they are likely to become entrenched power holders. If mass changes occur in the year of or following an election, political ousters likely motivate these changes.

The extent to which an individual moves among jobs affects the density of networks of social ties. If a job holder moves among multiple spheres, he or she will accumulate more ties than someone who moves back and forth between two jobs. I consider historical links to be stored in an individual’s biography as professional capital. Thus, an individual who once worked in a firm and transitioned to a ministry can call on acquaintances made in both positions. Upon moving to a third position, the individual’s built-up professional capital includes networks from both prior contacts. These links are not lost simply because he or she moves on to a new job. Quite to the contrary, such ties can be utilized to build coalitions, and his or her ability to span and connect to individuals in other organizations may be part of what makes him or her attractive as a new hire. Thus, if he or she moves between jobs in different sectors, he or she accumulates historical links to a variety of spheres.

As the data discussed below show, countries vary significantly. Stories about the movement of individuals between the public and private sphere are hardly particular to the post-socialist situation, but they raise interesting questions about the relationship between individual spheres of power and the dynamics of institution building, thus allowing the study of variation in levels and types of systemic influence construction. The pathways of bureaucrats once they leave a particular office are important because they reinforce the popular notion in post-socialist countries that bureaucratic interactions with those who lobby them are part of a longer-term plan to convert political power into other types of power, primarily economic power.1 As noted above, in most eastern European countries the practice of appointing state personnel to firms was a strategy pursued by political organizations to extend political control.2 A great deal has been written in the press about the process and purpose of these exchanges, but little more than anecdotal evidence has been offered to support macro-conclusions about its impact. One often hears, for example, of a bureaucrat being appointed to the board of a firm or an executive being appointed to some governing body in a process that is intended to extend or convert one kind of authority into another (Kublik Reference Kublik2008).

This practice is, of course, advantageous not only to political parties. It is also an attractive strategy to bureaucrats, because it generates “emergency exits” for those who face an uncertain future at each round of elections. For example, in Poland the members of the supervisory boards of the most important firms are also replaced after elections (Grzeszak et al. Reference Grzeszak, Markiewicz, Dziadul, Wilczak, Urbanek, Mojkowski and Pokojska1999; Staniszkis Reference Staniszkis2000). This applies to both public and private firms and is supported by journalistic accounts of individual cases. Similarly, ministerial positions, including lower-level positions, are reshuffled after each election. For example, on June 25, 1994, the leading Polish daily Gazeta Wyborcza commented in connection with the then prime minister, “The ease with which Pawlak’s team disposes of the best professionals at every level of the government and ministerial administration prompts amazement and dismay” (Vinton Reference Vinton1994).

These practices are in line with a minimal conception of the state in post-socialist countries that has emerged in the literature. The post-socialist state was initially considered to be an autonomous and strong actor that needed to be dismantled, because it was assumed that the socialist state had been a strong state. More recent studies, in particular Grzymała-Busse and Jones-Luong’s (Reference Grzymała-Busse and Jones-Luong2002) direct treatment of the question, have urged a reconsideration of these states as particularly weak, requiring rebuilding to meet new administrative challenges.

Yet rebuilding was unlikely to take place in the conventional fashion: by erecting new institutional structures that were legitimized and that bound actors in rule-following behavior. Even if the situation on the ground could have made this possible, pressure coming from international policy advisors tied the hands of the state and limited the extent to which state structures could take an active role in the construction of markets. As a consequence, alternative structures developed to link political and economic actors. For example, during this period state economic activities were largely controlled or bounded by clientelistic relationships with powerful actors who had the money or means to threaten the state. Political parties with access to decision-making authority were similarly drawn into this web of relations.

Thus, one promising avenue for a reconception of the state focuses on elites (Levi Reference Leff1998; Waldner Reference Waldner1999; Migdal Reference Meyer-Sahling2001; Grzymała-Busse and Jones-Luong Reference Grzymała-Busse and Jones-Luong2002), implicitly exploring the notion that the extension of state control and prestige is largely connected to the paths, networks, and initiatives of individuals. This reconception requires a shift toward considering the state as a non-unitary actor – one that operates through disjointed areas of influence that are in the process of consolidation while under pressure from social forces.

In this conception, pathways and relations are strategically deployed so as to maximize the career prospects of the individual and the organization vis-à-vis the state. Such strategic behavior aims to increase individual holdings in one or more of the key currencies in circulation: money, policy influence, and information. These paths form a macro-structural pattern of behavior, which all elites attempt to read and estimate in order to plan their next move. And, with each new move, the value of all members’ network capital grows.

Behind this conception is a particular assumption about the state and the individuals who constitute it. In the weak states considered here, politics penetrates all areas of the state, and individuals are part of this political structure more than they are part of the state agency in which they work. This dynamic can also be attributed to attitudes stemming from before 1989, when all positions were obtained through the ruling communist party. Rather than shedding this trend after transition, there is ample evidence that new political parties, such as the Polish SLD and AWS or the Bulgarian UDF and BSP, adopted it. Hence, it is useful to view the state as constituted by individuals in diffuse political organizations, in the sense that the individuals are not located in one particular place but have fanned out across a variety of social arenas, moving along mutually self-serving paths.

It follows that much can be learned by observing the macro-structural patterns of elite movement. When summed together, different patterns of movement will give rise to very different configurations of networks. In turn, this should lead to different types of states, as a greater or lesser number of individuals control or have access to a network that fulfills functions such as the transmission of information, the facilitation of coalition building, the creation of policy cliques, and an awareness of the interests in different policy arenas. Succinctly, networks facilitate or impede the group mobilization of resources.

By following the development of the networks below, I observe how the state comes to occupy a particular position of relational power. These ties are the “embeddedness” of which Evans and others have written, and which enables the state to make informed policy decisions that have the support of societal actors by taking advantage of the feedback that flows through these ties. The following pages analyze how state power and state consolidation were supported or constrained by the informal organization of networked individuals.

Anticipating the findings, the analysis indicates the importance of two dimensions. First, it highlights the role of elite mobility. I find a striking difference between the breadth of embeddedness in the three cases. The Polish network is much wider than the Bulgarian network, although elites are more mobile in the latter. In Poland, networks spread further and linked social spheres and power brokers more broadly over time. In Romania, network breadth is much lower and elites are much less mobile as a whole. The presence of broad relational contacts between the public and private sectors in Poland challenges the notion that network ties between elites generated many of the pathologies of post-socialist government. The lack of such ties in Romania and Bulgaria – countries known for their poor governance – provides negative cases.

Second, this analysis reveals very different patterns of movement between the state and sectors of the private economy. The closeness of certain areas of the private sector to the state go hand in hand with particular paths of institutional development. The frequent movement of individuals from the private sector into the state in Bulgaria is a central part of the story of state capture that has been told qualitatively elsewhere in the literature (Ganev Reference Ganev2001; Ganev Reference Ganev2007). This pattern is in stark contrast to the dominant movement in Poland: of party functionaries from the parliament to key ministries and sometimes private business. Romania represents a third variant, in which elites circulate from high positions within the state outward, although with far less frequency and more limited breadth.

How elite networks differ across countries

The argument in this chapter is based on a relational approach to the state. In political science, states generally continue to be conceptualized as black boxes. In some empirical studies, scholars explore the actual interactions of state bureaucrats with societal actors (Evans, Rueschemeyer, and Skocpol Reference Evans, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1985; Evans Reference Evans1995). Even in studies of the post-socialist countries, however, in which much of the political science literature has been focused on how ties between state bureaucrats and societal actors are responsible for corruption, there is a tendency to discuss what states “do” (Ledeneva Reference Ledeneva1998). Rarely, as a result, is the link made between the role that individual actors play and the enabling or constraining effects of individual relational ties.

One aim of this study is to develop a less unitary vision of the state and contribute with empirical substance to the conception of the state as an arena (Mann Reference Mann1984). The analysis thus uncovers how the networks of individual state bureaucrats contribute to the development of state power. To this end, it traces the development of these networks, which are difficult to observe, from a perspective that is available to researchers. As in the example of the Baron Rothschild discussed in Chapter 1, when we move to a temporal conception of networks, network approaches are able to capture both structure and agency. Thus, by observing the same network over time, we can observe the effect that structure has on individual choice within a network.

Summarizing the data presented below, Table 5.1 shows the sharp differences in personnel network development across countries. In the Polish case, networks were conditioned by high uncertainty in the form of frequent changes of the party in power, which led to the regular reshuffling of network ties because individuals were removed from their jobs by an external political shock (this is labeled in the table as the “Impact of elections”). Individuals also tended to move between sectors with a wider range than in the other two countries. As a result, the average individual occupied more positions, and the resulting career network linked many more individuals (this is labeled in the table as “Career heterogeneity”).

Table 5.1 Comparison of cases

In Bulgaria, ties were much more homogeneous but slightly more conditioned by political change over time than in Poland. Occupants of elite bureaucratic positions were significantly affected by electoral shocks and forced to switch jobs in post-election years. They also were highly mobile in non-election years. These moves tended to be within the same sector, however. Many simply returned to their pre-election positions once their own political party returned to power. As a result, Bulgarian personnel networks did not develop the same type of breadth as in Poland, and individual careers did not develop to link diverse organizations and sectors.

As a result of these network structures, Bulgaria became the victim of strong societal interests that had close ties to entrenched bureaucrats in key ministries, which is, in fact, a feature often identified to explain the laggardly performance of Bulgaria in building functional market institutions (Ganev Reference Ganev2007). The reasoning that is commonly implied – that networks link the early winners of reform, who colonize the state – is incorrect, however (Hellman Reference Hellman1998; Ganev Reference Ganev2001; Hellman, Jones, and Kaufmann Reference Hellman, Jones and Kaufmann2003). As previous chapters have shown in other contexts, what differentiates Poland from Bulgaria is not the presence of networks but their structure.

In all three countries, career networks were affected by elections. Electoral turnover is high in Poland and Bulgaria and weak in Romania, however. Thus, if a single quality marks the careers of Romanian state personnel, it is stability. Individuals in Romania change jobs less frequently, and these changes are not affected by electoral outcomes nearly to the extent that is true in the other cases.

Data

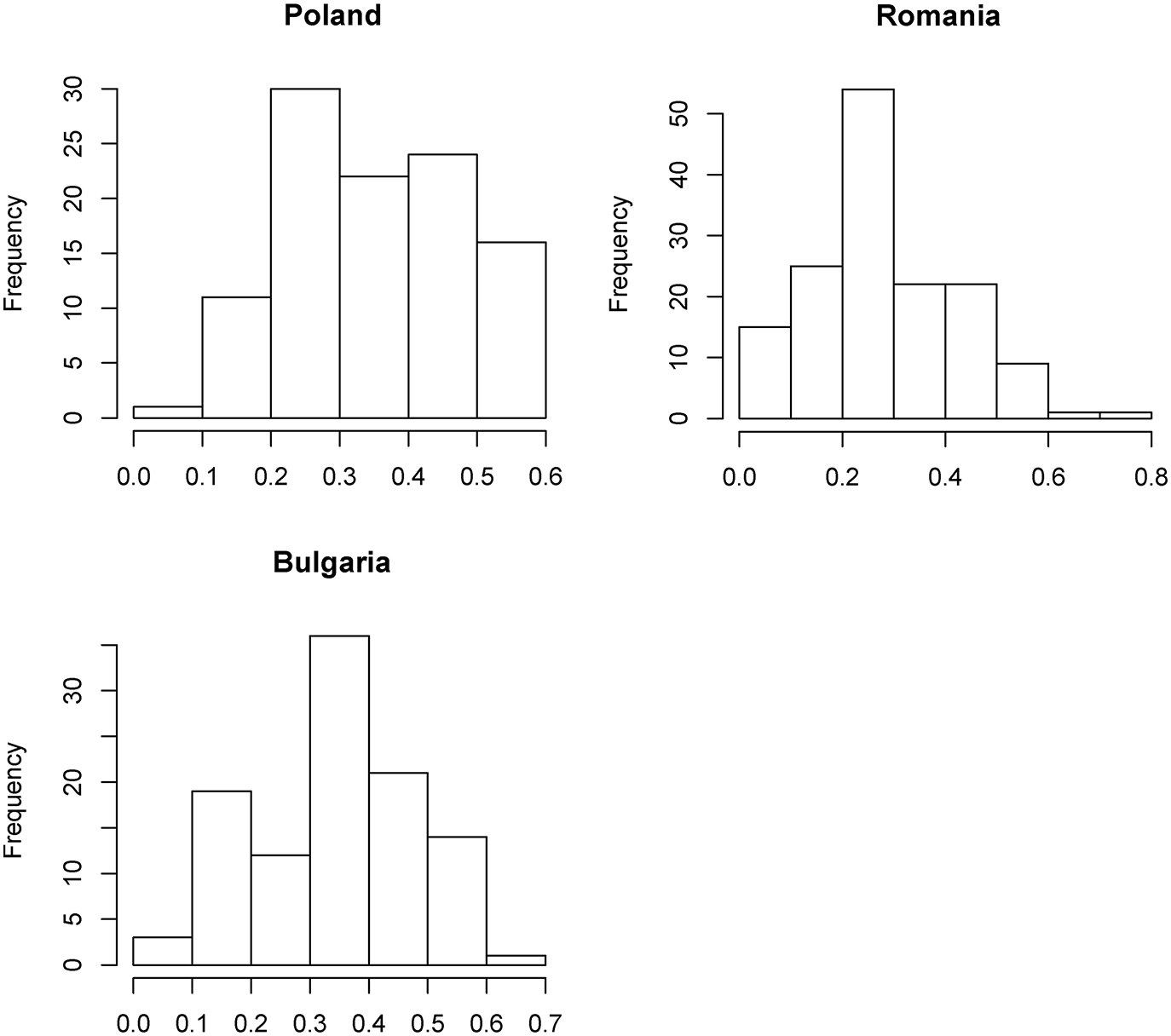

The data used here were collected in Bulgaria, Poland, and Romania. I first collected a list of ministers, deputies, secretaries, and undersecretaries in the Ministries of Finance, Economy, Industry and Trade, Interior, and Defense for all governments during the period 1993 to 2003. Subsequently, a database that included the career paths and declared political affiliations of these individuals for the entire period was compiled. For each person, his or her primary or full-time occupation was coded. The Polish data set covers the complete careers of 105 persons from 1993 to 2003, the Bulgarian dataset covers 106 individuals from 1992 to 2003, and the Romanian dataset covers 149 people from 1990 to 2005. Each cell was recoded into one of eighteen possible job categories culled from the whole range of jobs occupied by members of the data set. These categories are: “Ministry of Finance,” “Ministry of Economy,” “Ministry of Industry and Trade,” “Ministry of Interior,” “Ministry of Defense,” “Ministry of Foreign Trade,” “Other top government positions,” “Business organizations,” “International organization/EU,” “Labor unions,” “State firms,” “Private firms,” “NGOs” (non-governmental organizations), “Diplomatic corps,” “Senior military and police officials,” “Parliament,” “Political party,” and “Academic/journalist.” These were then recoded according to Table 5.2 into a reduced schema that captures the various sectors of society represented in the data set.

Table 5.2 Coding of data3

This database details joint membership in groups, parallels and divergences in the paths of individuals, and the potential “reach” that develops as the network becomes more connected. The codes represent the transformations undertaken by the governing elite as they moved between the state bureaucracy, the business sector (state and private), pressure groups in the NGO sector, international organizations, and the media.

Comparative network development

What macro-patterns can be identified in the data over time, and what differences emerge from a comparison of these three cases? The exploration of the data set described above highlights two dimensions in the configuration of elite career paths: (1) the impact of elections (which captures uncertainty by looking at the degree of mobility – i.e. the frequency of change in jobs); and (2) the range of career destinations (which captures network breadth). Pulling together the degree of mobility and destination range, career paths are a way to materially capture the different relationships between state and economy generated by the interaction of political uncertainty and network breadth.

The impact of elections

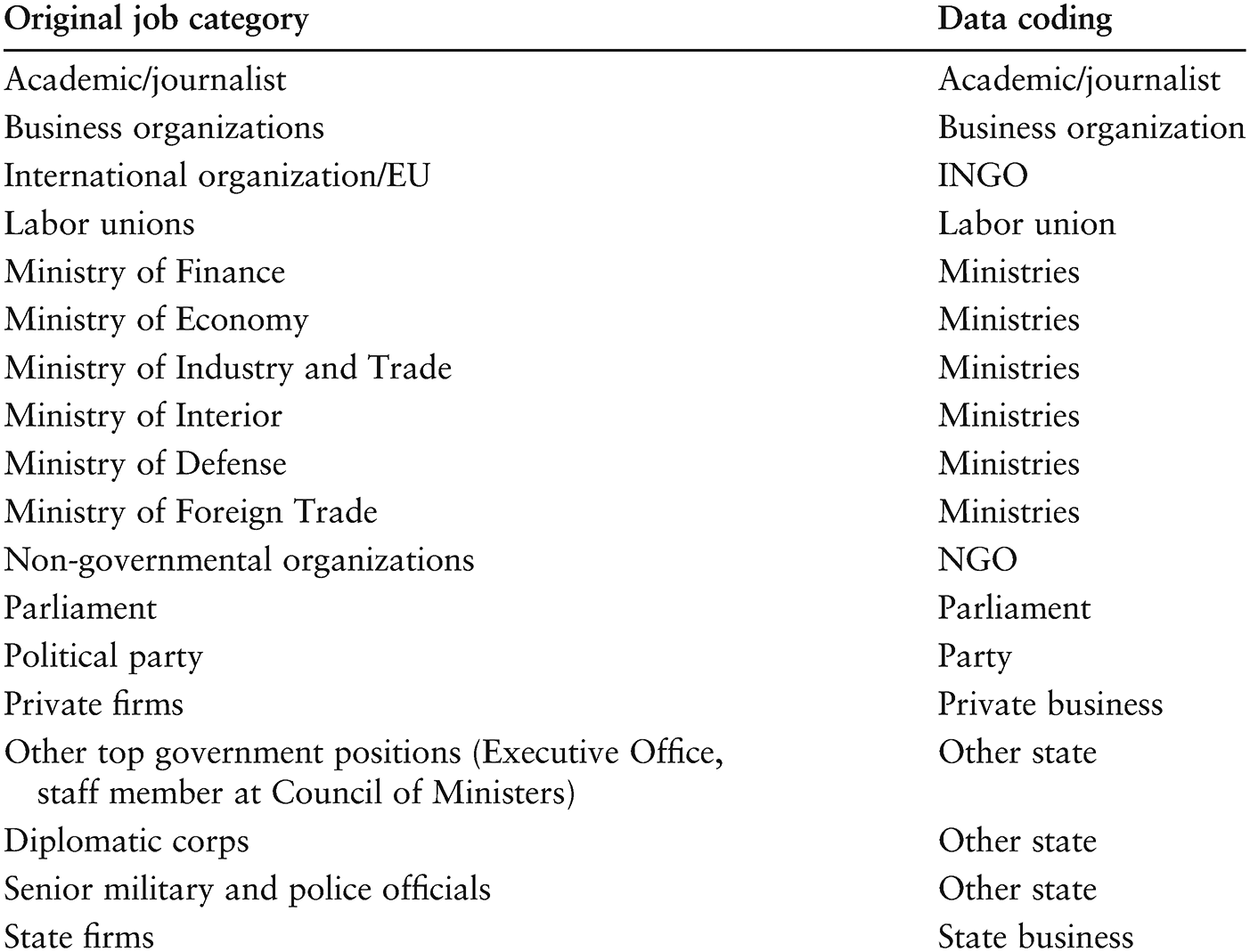

The stability of the network over time captures the extent to which individuals sit in their appointed positions. It expresses the amount of mobility or “turbulence” in the macro-social system as people shift across positions – the extent to which the broad system is disrupted. Some countries are generally more turbulent than others because their social systems – in this case the system of professional appointments – are subject to more frequent shifts. There are also some events that are turbulence-inducing. Elections are particularly significant events of this type. In all three cases in this book, elections bring about broad changes in the staffing of high-status jobs, indicating that high-level positions are political. The degree of such shifts varies, however. The job of an individual at any given time can be considered a state, and a career as a sequence of states. Figure 5.1 captures the average number of transitions across states in non-election years and post-election years.

Figure 5.1 Yearly average of elites changing jobs

Note: Average percentage of job turnovers per year.

The Romanian career network experiences the lowest number of state transitions per year in the year following an election. Individuals there are also highly unlikely to change jobs in any given year, although their chances of doing so rise in post-election years – as they do in other countries. This result is driven by the changes that took place after the 1996 victory of a broad coalition of parties that first interrupted the Social Democrats’ hold on power after 1989. In other periods, the Romanian network experienced much less change. In any given non-election year an average of only 15 percent of individuals in this data set shifted career state.

By contrast, the Bulgarian network was highly turbulent; in any given year nearly a quarter of all individuals shifted jobs. In post-election years more than 35 percent were affected by job changes. Poland is much like Bulgaria: a highly fluid and deeply politicized society in which elite positions in both the public and the private sector are awarded according to political affiliation.

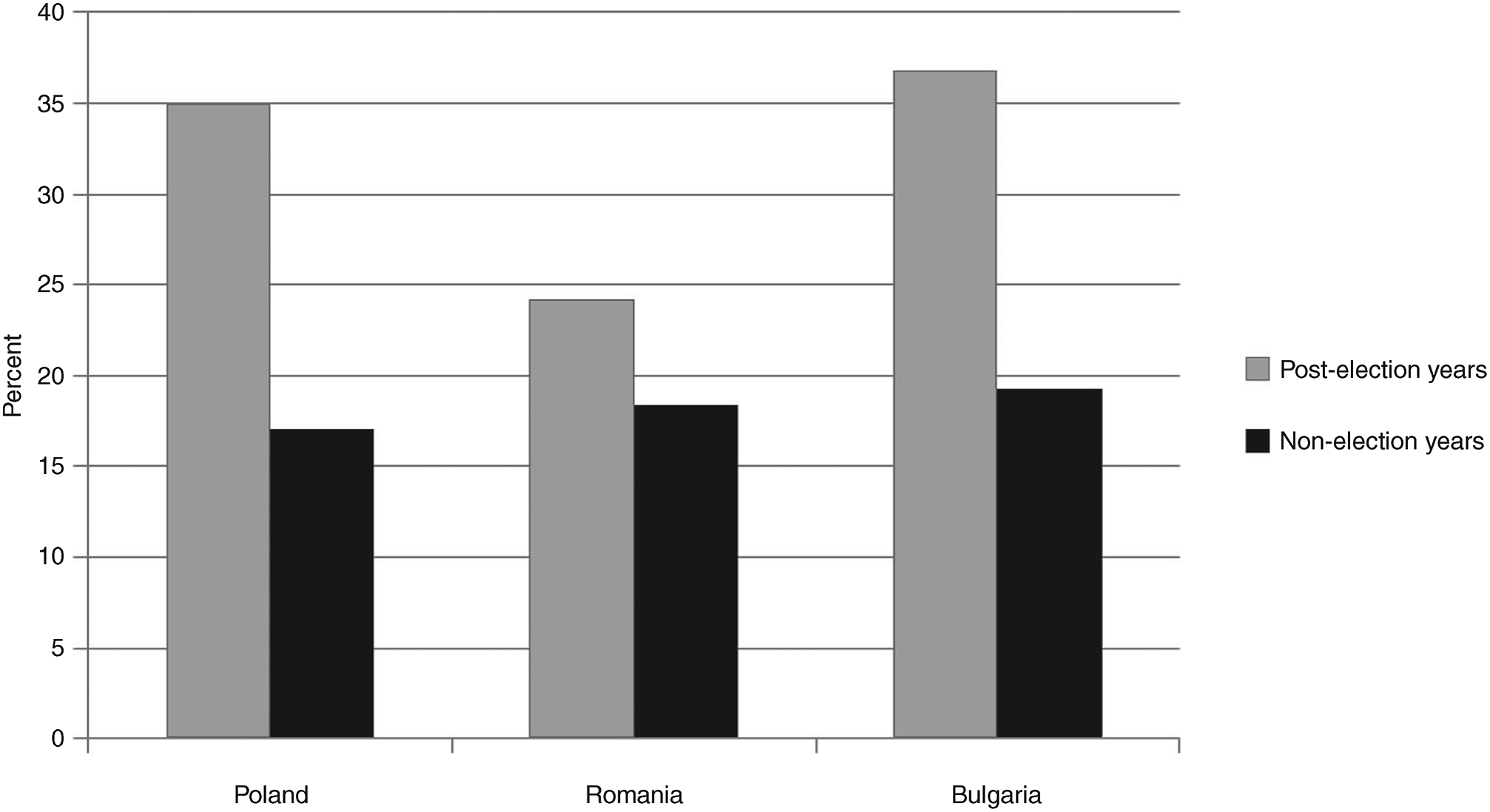

Considering the distribution of different levels of state transition in a population also reveals sharp differences between the cases. One useful measure is sequence entropy.4 If each individual career is considered a sequence of states, then sequence entropy can be interpreted as the “uncertainty” of predicting the states in a given sequence. Sequence entropy is measured on a normalized scale of 0 to 1. If all states in the sequence are the same over time, the entropy is equal to 0. If every state is different, the value is 1. Values reported here are normalized and comparable across country data sets. The distribution of sequence entropies is shown in Figure 5.2, which presents frequency distributions for levels of sequence entropy in each country.

Figure 5.2 Sequence entropy by country

The variance is striking. Romania has a stable and static social system and is different from the other two cases, which experience a much higher degree of individual mobility. Poland and Bulgaria also differ in the extent to which individuals move, however. In Poland, the general population of elites shifts jobs regularly, with about 60 percent of the sample being highly mobile and transitioning through many jobs over the course of a career. By contrast, Bulgaria’s elite tends not to transition through quite as many jobs, and a concentrated group of individuals is much more mobile than the rest of the population, as can be seen in the more bell-shaped distribution of frequencies.

The frequency of shifts reflects the extent to which individuals become entrenched office holders. Whereas, in Poland, no one can afford to be too comfortable in a given post, and this is true across the population in the public and private sectors alike, in Bulgaria only a subset of individuals is affected by the political forces that lead to frequent state transitions. The vast majority in Romania, instead, experience very few state changes. The distribution does indicate that some of those in a political office shift position, but they move on to a new job in which they are likely to become entrenched power holders. The great majority have quite stable careers.

The effect of network breadth

The previous dimension captures the extent to which political shocks determine mobility. The analysis confirms that Romania is a country with little mobility, in response to a static political environment, while the elite in Poland is subject to frequent moves. Bulgaria is similar to Poland, although the elite is slightly less mobile.

Another important component for the argument is the extent to which accumulated contacts in any given country give an individual access to a heterogeneous network. In other words, the breadth of networks linking the state and the economy determines the range of opportunities for career shifts. One can imagine that, at every transition, individuals either fan out across the economy to take up positions in other sectors or perhaps return to an organization in which they previously held a job. The first is a more open system, in which individuals enjoy broad access to different types of organization. This produces individuals with diverse contacts, and organizationally benefits an elite that is jointly seeking to solve search and coordination problems. The second is much less open. Individuals move less, and, when they do move, they are less likely to change organizations or sectors. Instead, they seek or are placed into entrenched positions of power. As an elite system, this second variant is well suited to small groups seeking to address problems of collaboration – behavior that may even be called collusion.

Thus, the analysis now turns to the ties that were formed by individuals changing jobs. A single tie between two organizations means that an individual worked in both and thus provides a human link between them. For example, if a single Romanian bureaucrat worked in the Ministry of Finance and then moved to work in the private business sector, he or she provides a single human pathway between two organizations and two spheres of the social world: the state and the private economy.

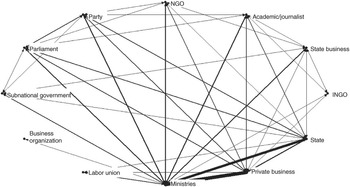

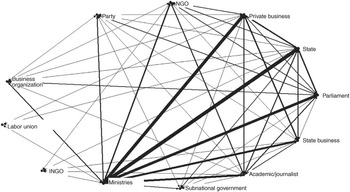

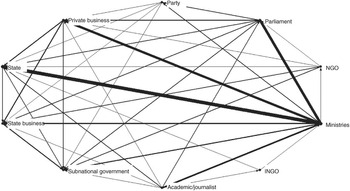

The graphics in Figures 5.3 to 5.5 were obtained by comparing the same eleven-year period for each country (1993–2003). The networks are presented in Figures 5.3 for Bulgaria, 5.4 for Poland, and 5.5 for Romania. These images represent the connectedness of the network at the end of the whole period under study. Although the networks pictured here actually represent a three-dimensional web that includes time, the two-dimensional image shows the state of the network at the end of 2003 and includes all of the relations that were formed from the first year of observation, 1993.

Figure 5.3 Bulgarian network of ties between social sectors, 1993–2003 Notes: Thickness of lines indicates density of ties. “Other state” is labeled “State” in order to minimize clutter.

Figure 5.4 Polish network of ties between social sectors, 1993–2003. Notes: Thickness of lines indicates density of ties. “Other state” is labeled “State” in order to minimize clutter.

Figure 5.5 Romanian network of ties between social sectors, 1993–2003. Notes: Thickness of lines indicates density of ties. “Other state” is labeled “State” in order to minimize clutter.

Thicker lines mean that more ties are present between two organizational nodes. Hence, the graphs give a cumulative historical impression of the network ties for all individuals in the data set in each country. These images convey information on both network breadth and the degree of mobility (discussed in the previous section). The latter is rendered by the thickness of the lines. Thus, the network graphs depict the relative interconnectedness of different social spheres throughout the period.

Previous analysis showed that, as a consequence of the high degree of political uncertainty, Polish and Bulgarian elites display high mobility, while Romanian elites are more stable. Figure 5.3 shows that, although Bulgaria is a country in which elites shift frequently among jobs, these shifts are limited to a few sectors. The densest ties are among ministries and other top state positions, and between ministries and the private business sector. Parliamentarians, for example, do not often seek or are not often recruited to jobs in the private sector. Business organizations are of little interest as a career destination at all, except for a few individuals, who go no further. The same can be said of labor unions. In all, these three organizational spheres are poorly networked to other social sectors. By contrast, private business is a core origin and destination in the network. In fact, Table 5.3 shows that individuals move most from private business to ministerial positions and, to a lesser extent, from ministerial positions in the core ministries back to other state positions.

Table 5.3 Most common career transitions

Notes: Descending order of frequency. Count in parentheses.

In comparison, the Polish network shown in Figure 5.4 is much more broadly connected. This high mobility is spread out but especially focused between state bureaucratic positions, private business, state business, and parliament. This fits with the analysis presented in Chapter 3, which indicated mechanisms of control through personnel appointments in a variety of areas.

Romania has developed yet a different configuration, as shown in Figure 5.5. State and private business are both far less popular linkages. Further, because the system has a dominant party, the sphere of influence is parliament and bureaucracy rather than the market. This is the fundamental difference between Romania and Bulgaria. Business organizations are peripheral in Bulgaria, somewhat better connected in Poland, and do not appear at all in the Romanian network, meaning that no one who held a ministerial job also held a position in a business organization. This indicates strongly that the institutionalized representation of business is of marginal consequence. The same can be said of labor unions.

In reading these network graphs, it is important to keep in mind that the lack of movement to a sector does not mean that institutions in that social sphere do not play an important role in society. Instead, it indicates that those organizations are not sites that are being contested between elite groupings. For example, NGOs in Bulgaria are probably not an important destination, because many are already politically loyal to a single party and most do not have much influence on policy in Bulgaria. Some NGOs are known to be intermediaries of illegal party finance to political parties, however, and are established by the parties for this purpose. For example, when the UDF gained control of the government in 1997, it began to privatize companies that were performing well to investors allied with their party. These privatizations were allegedly reserved for investors who made donations to party-allied foundations. One such foundation, the Future of Bulgaria, was headed by Elena Kostova, the wife of the then prime minister (Standart 2001). Thus, NGOs can be important to elite groupings, but their political nature removes them from the struggle that is captured in these network graphs.

The sequence analysis shown in Table 5.3 confirms and expands on the differences shown in the network graphs by listing the most common transitions. In Bulgaria, the most common transition is between private business and core ministries. This shows the unique relation between private business and the state in Bulgaria. The dominant movement is from the private sector inward to state functions. Whereas Bulgaria is a state colonized by business, Poland is a state penetrated by political parties via parliament. Here, the dominant move is for party functionaries to take on elite state roles. The post-communist transition in Poland could be said to have been a move from a “party state” to a “parties’ state.” Romania, on the other hand, is an ossified social system in which a set of state elites dominates and has spread to other spheres. While in Bulgaria societal actors move inward to the state, Romanian state elites cycle between bureaucracy and government. The lack of early coherent political competition set up entrenched areas of influence that continue to slow reform progress. Beyond this, the state and the economy are clearly separate spheres, with little sharing of accumulated human capital.

Conclusion

The dynamics discussed above coincide with the characterizations of state types – the patronage state (Romania), the captured state (Bulgaria), and the concertation state (Poland) – set out at the beginning of this book. The analyses operationalize and reveal variation in embeddedness, a dimension of state–society relations that frequently figures in arguments about institutional development. The breadth or narrowness of networks – the extent to which distant individuals are connected to each other and have developed ties by working in the same places – structures their ability to engage in collective action.

While Romania is marred by career stability that stems from party dominance, Bulgaria and Poland display a high frequency of job changes, reflecting their turbulent political environments. Poland developed more autonomous institutions with less entrenched interests, however, while Bulgaria became the victim of strong societal interests that had close ties to entrenched bureaucrats in key ministries.

The implication is that we must adjust our understanding of network ties and consider uncertainties such as the role of elections in shaping and disturbing networks and the extent of individual mobility or entrenchment when theorizing about the role that societal actors play in the development of state power. The key lesson of this qualitative and quantitative comparison is that under high uncertainty, when networks are conditioned by political alternation, individuals circulate more often. The emergence of collective action depends on the combination of mobility and the range of career destinations, however. The greater the number of sectors in the public or private spheres, the broader the network of accumulated human capital and the larger the resources to bridge collective action among elites.

1 Such activity is not restricted to the post-socialist area. The conversion of public into private power is known as the amakudari system in Japan or the often referred-to “golden parachute,” which is in the toolbox of bureaucrats from Peru to Norway. The amakudari system and others like it in east Asia developed in order to create channels of control, however, and the implementation of industrial policy through official as well as personal pathways.

2 An impressive body of press articles exists on individual episodes. References to a “system” of politics that underpins it were first made in an interview with a prominent political commentator in Warsaw in May 2000.

3 The category “Other state” was distinguished from the four core ministries in order to study specifically the career and recruitment patterns of individuals who served in the ministries that deal with regulation of the economy as well as strategic economic sectors.

4 Sequence entropy was calculated using TraMineR in R. For more information about sequence entropy, see Gabadinho et al. (Reference Gabadinho, Ritschard, Studer and Müller2011).