Depression and decision-making

Depression is the most frequent psychiatric disorder and the third most frequent cause of disability-adjusted life-years.1,Reference Vigo, Thornicroft and Atun2 The majority of patients with depression are eligible to receive treatment, which includes different psychological and pharmacological interventionsReference Ramanuj, Ferenchick and Pincus3,Reference Malhi and Mann4 that seem to have similar efficacy.Reference Cuijpers, Vogelzangs, Twisk, Kleiboer, Li and Penninx5,Reference Farah, Alsawas, Mainou, Alahdab, Farah and Ahmed6 However, patients with depression frequently have low accessReference Chekroud, Foster, Zheutlin, Gerhard, Roy and Koutsouleris7 and adherence to depression treatment.Reference Sansone and Sansone8

Patients with depression want to receive more information about their disorder, and participate in their health-related decisions.Reference Arora and McHorney9,Reference Patel and Bakken10 In this sense, shared decision-making is an approach for patient-centred care that seeks to actively involve patients in the decision-making process of choosing between two or more medically acceptable and evidence-based treatment options.Reference Hargraves, LeBlanc, Shah and Montori11 It is hypothesised that active patient involvement empowers the patient and could improve treatment adherence and satisfaction rates, which may result in better treatment effectiveness.Reference Bertakis and Azari12–Reference Roumie, Greevy, Wallston, Elasy, Kaltenbach and Kotter14

Decision aids in depression

Decision aids are the main tools used to facilitate shared decision-making and support patients in making informed choices.Reference Kroenke15 These materials are developed in different formats (paper, video, web-based tools, etc.), and describe the condition and the benefits and harms of each treatment option, and encourage patients to identify which outcomes are the most important for them when making a choice.Reference Elwyn, O'Connor, Stacey, Volk, Edwards and Coulter16,Reference Perestelo-Perez, Rivero-Santana, Sanchez-Afonso, Perez-Ramos, Castellano-Fuentes and Sepucha17 Usually, these interventions have to be adapted according to specific population needs, considering the context of their application.Reference Chenel, Mortenson, Guay, Jutai and Auger18 The decision aids mainly seek to improve patient knowledge, decisional conflict and patient–clinician communication.Reference Wieringa, Rodriguez-Gutierrez, Spencer-Bonilla, de Wit, Ponce and Sanchez-Herrera19 Additionally, they have also been studied to explore their clinical effects, such as treatment adherenceReference Stalmeier20 or reduction of symptoms.Reference Geerse, Stegmann, Kerstjens, Hiltermann, Bakitas and Zimmermann21

Although the use of decision aids may cause benefits such as higher treatment adherence and, therefore, higher clinical improvement, it may also cause harm, such as an increased level of patient stress.Reference Seale, Chaplin, Lelliott and Quirk22 In addition, people with major depressive disorder could have abnormal decision-making behaviour in a social interaction context because of an altered sensitivity for reward and punishment, reduce experiences of regret and poor decision performance.Reference Wang, Zhou, Li, Wang, Wu and Liu23 This situation could also affect the use of decision aids in patients with depression.

Regarding decision aids for depression treatment, there is still concern about the benefit–harm balance, although some studies have assessed their effects. Therefore, this systematic review aimed to search for randomised clinical trials (RCTs) to assess the effects of decision aids on the shared decision process and clinical outcomes in adults with depression.

Method

The protocol for this systematic review has been registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; identifier CRD42019121878). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Human Medicine Faculty of Ricardo Palma University (CE-8-2019).

Literature search and study selection

For this systematic review, we included all RCTs that included adults with any type of depression. These RCTs must have compared a group that received a decision aid that aimed to help patients decide about their treatment for any kind of depression treatment (as a stand-alone intervention, or as the main element within a complex intervention) with a group that did not, and directly assessed any beneficial or adverse effects in adults with depression. We excluded RCTs that had as population only pregnant women because they have different risks that should be considered when deciding whether to use antidepressants.Reference Wichman and Stern24 Also, we excluded conference papers. There were no restrictions on language or publication date.

Decision aids were defined as tools or technologies used to help patients make informed decisions by offering information about treatment options, and help them to construct, clarify and communicate their values and preferences.Reference Volk, Llewellyn-Thomas, Stacey and Elwyn25 However, sometimes it is difficult to differentiate from other information-based interventions.Reference Lenz, Buhse, Kasper, Kupfer, Richter and Muhlhauser26 To define if the proposed intervention was a decision aid, we used the six-item qualifying criteria for decision aids developed by the International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration, as it provides the definition standards for decision aids: (a) describes the health condition or problem for which the index decision is required, (b) states the decision that needs to be considered, (c) describes the options available for the index decision, (d) describes the positive features of each option, (e) describes the negative features of each option and (f) describes what it is like to experience the consequences of the options.Reference Joseph-Williams, Newcombe, Politi, Durand, Sivell and Stacey27

The decision aid assessed by the RCTs needed to meet all six criteria to be included in our systematic review.

A literature search was performed in two steps: a systematic review of five databases, and a review of all documents cited by any of the studies included in the first step. For the first step, we performed a literature search in five databases: Medline, EMBASE, Scopus, Web of Science and ClinicalTrials.gov. We used terms related to decision support, decision aid, decision-making, depression and clinical trials. The complete search strategies for each database are available in Supplementary File 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2020.130. The last update of this database search was performed on 5 January 2019. Duplicated records were removed with EndNote version X8 for Windows (Clarivate Analytics, Thomson Reuters, New York; see https://endnote.com/). After that, titles and abstracts were independently screened by two pairs of independent reviewers (C.A.A.-R. with M.E.D.-B., and N.B.-C. with C.J.T.-H.) to identify potentially relevant articles for inclusion. This was performed with the online software Rayyan version 01 for Windows (Qatar Computing Research Institute, Qatar Foundation, Qatar; see https://rayyan.qcri.org).Reference Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz and Elmagarmid28 Disagreements were resolved through a discussion with a third reviewer (J.H.Z.-T.). Then, the full text of potentially relevant articles were assessed to evaluate their eligibility. This process was also independently performed by two researchers. The complete list of excluded articles at this full-text stage is available in Supplementary File 2.

For the second step, two independent reviewers (M.E.D.-B. and N.B.-C.) assessed all documents listed in the references section of the studies selected in the first step, and collected all articles that fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data extraction

Two independent researchers (C.A.A.-R. and M.E.D.-B.) extracted the following information from each of the included studies into a sheet of Microsoft Excel version 2018 for Windows: author, year of publication, title, population (inclusion and exclusion criteria), setting, intervention (name, type, the methodology of application and length of use), comparator (name, type, the methodology of application and length of use), time of follow-up and effects of decision aid in all included outcomes.

Intervention information was collected with the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist.Reference Hoffmann, Glasziou, Boutron, Milne, Perera and Moher29 The checklist originally was designed for pharmacological interventions; thus, we included only the following items, adapted for more complex interventions: name of intervention, rationale, location of delivery, materials, procedures, who provided, modes of delivery (grouped or individual), frequency (sessions) and possible options to choose within the decision aid. In case of disagreement, the full-text article was reviewed again by the researchers, to reach a consensus.

Study quality and certainty of the evidence

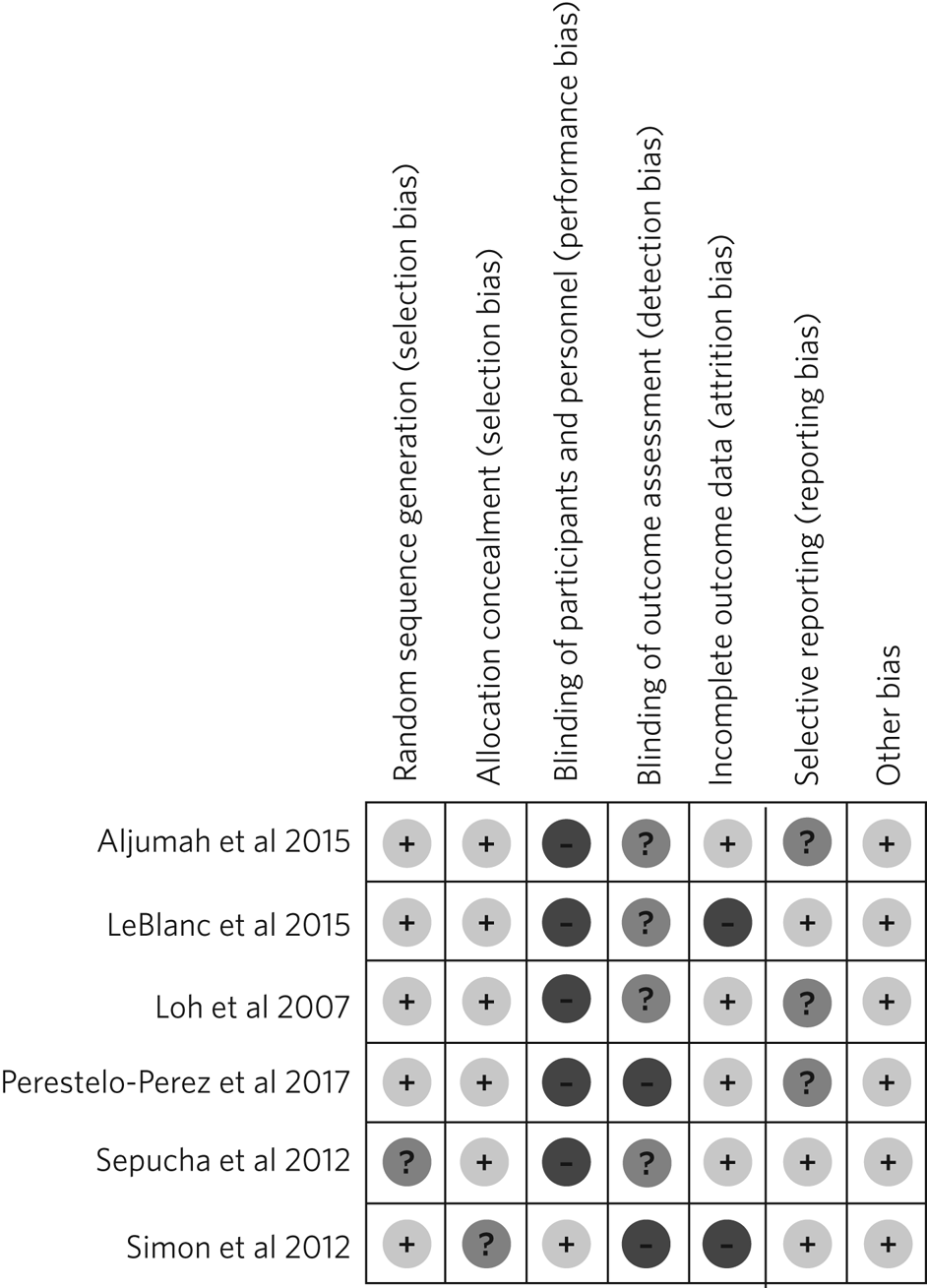

Two independent researchers (C.A.A.-R. and N.B.-C.) used the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for RCTs to assess systematic errors (or bias) in the design, conduct, analysis and reporting of the RCT that could potentially underestimate or overestimate the results.Reference Higgins, Altman, Gotzsche, Juni, Moher and Oxman30 We followed the instructions stated in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and evaluated selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias and reporting bias to assess each of the six domains of the tool as low, high or unclear risk of bias, by each RCT included in the systematic review.Reference Deeks, Higgins, Altman and Green31

To assess the certainty of the evidence, we used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology,Reference Balshem, Helfand, Schunemann, Oxman, Kunz and Brozek32 which classifies it in a very low, low, moderate or high certainty of the evidence each outcome in the systematic review. This classification is based on the following criteria: risk of bias (evaluated through the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool), inconsistency (heterogeneity between the RCT results and in terms of population, intervention, comparator and outcome; additionally assessed by the I 2 test), indirectness (how different are the included RCTs to the question of interest) and imprecision (wideness of the confidence interval). The certainty of the evidence was assessed for all meta-analysed outcomes and non-meta-analysed outcomes that were important for decision- making. Additionally, when two or more RCTs assessed the same outcome, but a meta-analysis was not performed, we summarised the individual data of each RCT narratively, and then assessed the certainty of the evidence following the recommendations proposed by Murad et al.Reference Murad, Mustafa, Schunemann, Sultan and Santesso33

Statistical analyses

We performed meta-analyses to summarise the results of the RCTs that evaluated the same outcomes. When outcomes were measured with different scales across studies, we calculated standardised mean differences (SMD) to compare and meta-analyse these studies; otherwise, we calculated weighted mean differences (WMD). For outcomes that had been measured more than once, we only considered the final measurement to perform the meta-analyses, as suggested in the Cochrane Handbook.Reference Deeks, Higgins, Altman and Green31 We assessed heterogeneity with the I 2 statistic, and we considered that heterogeneity might not be significant when I 2 < 40%.Reference Deeks, Higgins, Altman and Green31 We considered it appropriate to use random-effects models in all the meta-analysis because of the overall heterogeneity in terms of population, intervention and comparators.Reference DerSimonian and Laird34 We executed a sensitivity analysis, taking into account contradictory results within studies. We did not considerer to exclude studies with high risk for bias for sensitivity analysis, because all the included RCTs had at least one domain of the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool with a high risk of bias. Also, we did not execute a subgroup analysis because of the low number of studies by each meta-analysis. Publication bias was not statistically assessed because the number of studies pooled for each meta-analysis was less than ten.Reference Deeks, Higgins, Altman and Green35 The data were processed with Stata version 15.0 for Windows.

Results

Studies characteristics

We found a total of 3309 titles. We removed 804 duplicates and screened a total of 2505 titles, of which 41 were evaluated in full text. Of these, 35 were excluded (reasons for exclusion are detailed in Supplementary File 2) and six were included.Reference Perestelo-Perez, Rivero-Santana, Sanchez-Afonso, Perez-Ramos, Castellano-Fuentes and Sepucha17,Reference Sepucha, Gallagher and Cosenza36–Reference Simon, Kriston, von Wolff, Buchholz, Vietor and Hecke40 Additionally, we evaluated 255 documents cited by any of the six included studies, from which no additional study was included (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Flow diagram (study selection). RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Patient characteristics

In the included RCTs, the number of participants ranged from 147 to 1137. Regarding the study setting, three studies were performed in primary care centres,Reference Perestelo-Perez, Rivero-Santana, Sanchez-Afonso, Perez-Ramos, Castellano-Fuentes and Sepucha17,Reference LeBlanc, Herrin, Williams, Inselman, Branda and Shah38,Reference Loh, Simon, Wills, Kriston, Niebling and Harter39 one in out-patient clinicsReference Aljumah and Hassali37 and two were performed remotely (one intervention was sent by mail to the participantsReference Sepucha, Gallagher and Cosenza36 and one was an online interventionReference Simon, Kriston, von Wolff, Buchholz, Vietor and Hecke40). With regards to depression diagnosis for inclusion criteria, two studies used the Patient Health Questionnaire-9,Reference LeBlanc, Herrin, Williams, Inselman, Branda and Shah38,Reference Loh, Simon, Wills, Kriston, Niebling and Harter39 one study used the DSM-IV,Reference Aljumah and Hassali37 one study used the DSM-IV and the ICD-10,Reference Perestelo-Perez, Rivero-Santana, Sanchez-Afonso, Perez-Ramos, Castellano-Fuentes and Sepucha17 one used self-report criteriaReference Simon, Kriston, von Wolff, Buchholz, Vietor and Hecke40 and another did not specify the diagnosis criteria.Reference Sepucha, Gallagher and Cosenza36 Also, only one study specified the severity of depression according to the inclusion criteria.Reference LeBlanc, Herrin, Williams, Inselman, Branda and Shah38 Characteristics of each included study are available in Supplementary File 3.

Interventions and comparators

Interventions were heterogeneous across studies; four studies used visual decision aid (leaflets, booklet, cards or DVD),Reference Sepucha, Gallagher and Cosenza36–Reference Loh, Simon, Wills, Kriston, Niebling and Harter39 and two studies used a computer-based decision aid (webpage or artificial intelligence).Reference Perestelo-Perez, Rivero-Santana, Sanchez-Afonso, Perez-Ramos, Castellano-Fuentes and Sepucha17,Reference Simon, Kriston, von Wolff, Buchholz, Vietor and Hecke40 Regarding the decision aid application: in two studies, physicians applied the decision aids,Reference LeBlanc, Herrin, Williams, Inselman, Branda and Shah38,Reference Loh, Simon, Wills, Kriston, Niebling and Harter39 in two studies the decision aids were self-applied,Reference Perestelo-Perez, Rivero-Santana, Sanchez-Afonso, Perez-Ramos, Castellano-Fuentes and Sepucha17,Reference Sepucha, Gallagher and Cosenza36 in one study the decision aids were applied by a pharmacistReference Aljumah and Hassali37 and in one study decision aids were applied by artificial intelligence.Reference Simon, Kriston, von Wolff, Buchholz, Vietor and Hecke40 All decision aids presented possible options regarding the patient's depression treatment. Specifically, four decision aids presented options for the of use antidepressant drugs, psychotherapy/psychological treatment or watchful waiting.Reference Perestelo-Perez, Rivero-Santana, Sanchez-Afonso, Perez-Ramos, Castellano-Fuentes and Sepucha17,Reference Aljumah and Hassali37,Reference Loh, Simon, Wills, Kriston, Niebling and Harter39,Reference Simon, Kriston, von Wolff, Buchholz, Vietor and Hecke40 Furthermore, two decision aids presented options for start, stop, increase or switch antidepressant treatment.Reference Sepucha, Gallagher and Cosenza36,Reference LeBlanc, Herrin, Williams, Inselman, Branda and Shah38 Intervention's characteristics are detailed in Supplementary File 4, using the TIDieR checklist. Regarding the control group, in five studies, participants received either usual care or no intervention, and in the remaining study, the decision aid was compared with an informative intervention.Reference Simon, Kriston, von Wolff, Buchholz, Vietor and Hecke40

Outcomes

Included RCTs assessed a wide variety of outcomes, including decision-making process outcomes, such as decisional conflict, information exchange, patient knowledge, patients involvement in decision-making, decision regret, etc. Decisional conflict is known as the degree of patient insecurity about possible consequences that occur after deciding their health,Reference O'Connor41 and information exchange assess the communication between doctor and patient about their illness and its management when there is a need to decide on patient's health.Reference Lerman, Brody, Caputo, Smith, Lazaro and Wolfson42 Additionally, there are also clinical outcomes (such as depressive symptoms, adverse effects, treatment adherence and health-related quality of life). All the measured outcomes and definitions, by each RCT, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Outcomes evaluated in the included studies

EuroQol-5D, European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9; PHQ-D, Der Gesundheitsfragebogen für Patienten (Patient Health Questionnaire in German version); CSQ-8, Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8.

a. Results not presented in the paper.

Risk of bias

Regarding the risk of bias, mostly all RCTs detailed random sequence and allocation concealment. Two RCTs presented a high risk of attrition bias because they some participants were lost to follow-up. Furthermore, three RCTs had an unclear risk of bias for selective reporting. All six RCTs failed to blind the outcome assessment, and five RCTs failed to blind personnel and participants (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Risk of bias in the selected studies.

Effects on decision-making process outcomes

When pooling the RCTs, we found that decision aids had a beneficial effect on information exchange (two RCTs; WMD 2.02; 95% CI 1.11–2.93), patient knowledge (four RCTs; SMD 0.65; 95% CI 0.14–1.15) and decisional conflict, which refers to patient insecurity about the possible consequences that occur after deciding their health (three RCTs; WMD −5.93; 95% CI −11.24 to −0.61). Additionally, we found no statistically significant effect on doctor facilitation (two RCTs; WMD 1.40; 95% CI −4.37 to 7.18).

Regarding the outcome of patient involvement in the decision-making process, two RCTs present their results for this outcome, but each of them used a different instrument and perspective of assessment. Loh et alReference Loh, Simon, Wills, Kriston, Niebling and Harter39 used the Man-Son-Hing scale (patient perspective) and found a statistical difference between study groups (mean difference 2.5; 95% CI 1.6–3.4). Alternatively, LeBlanc et alReference LeBlanc, Herrin, Williams, Inselman, Branda and Shah38 used the Observing Patient Involvement in Decision-Making scale (evaluator perspective), and also found a statistical difference between study groups (mean difference 15.8; 95% CI 6.5–25.9).

The remaining decision-making process outcomes were assessed only by one RCT, and we did not find differences between the study groups in terms of length of consultation,Reference Loh, Simon, Wills, Kriston, Niebling and Harter39 decisional control preference (between passive, active or shared)Reference Perestelo-Perez, Rivero-Santana, Sanchez-Afonso, Perez-Ramos, Castellano-Fuentes and Sepucha17 and decision regret.Reference Simon, Kriston, von Wolff, Buchholz, Vietor and Hecke40 However, we found a beneficial effect to be sure of the intention to choose a treatment (sure or not sure),Reference Perestelo-Perez, Rivero-Santana, Sanchez-Afonso, Perez-Ramos, Castellano-Fuentes and Sepucha17 in the treatment satisfaction,Reference Aljumah and Hassali37 in the decision aid satisfactionReference LeBlanc, Herrin, Williams, Inselman, Branda and Shah38 and the preparation of patients for decision-making.Reference Simon, Kriston, von Wolff, Buchholz, Vietor and Hecke40

Effects on clinical outcomes

We did not find beneficial effect on treatment adherence (three RCTs; SMD 0.20; 95% CI −0.31 to 0.71), and depressive symptoms (three RCTs; SMD −0.06; 95% CI −0.22 to 0.09) (Fig. 3). Also, one RCT evaluated one adverse effect, mortality, and reported no adverse effects in both intervention and control arms,Reference Sepucha, Gallagher and Cosenza36 and another one found no differences between study groups for health-related quality of life.Reference Aljumah and Hassali37

Fig. 3 (a) Forest plot of decision aid for decisional conflict, higher is worse. (b) Forest plot of decision aid for patient knowledge, higher is better. (c) Forest plot of decision aid for depression symptoms, higher is worse. (d) Forest plot of decision aid for treatment adherence, higher is better. (e) Forest plot of decision aid for doctor facilitation, higher is better. (f) Forest plot of decision aid for information exchange, higher is better. SMD, standardized mean differences; WMD, weighted mean differences.

Sensitivity analysis

Three of the performed meta-analyses had important heterogeneity (I 2 > 40). Of these, only the meta-analysis performed for treatment adherence (three RCTs; SMD 0.20; 95% CI −0.31 to 0.71) included studies with contradictory results. Thus, we executed a sensitivity analysis for this outcome, excluding the RCT by Simon et al,Reference Simon, Kriston, von Wolff, Buchholz, Vietor and Hecke40 because its results contradicted the other results of the two RCTs by Loh et al and Aljumah et al.Reference Aljumah and Hassali37,Reference Loh, Simon, Wills, Kriston, Niebling and Harter39 The global effect of this sensitivity analysis, with only two RCTs, was an SMD of 0.50 (95% CI 0.29–0.70).

Certainty of evidence

We created a Summary of Findings table, using the GRADE methodology to assess the certainty of evidence. For this, we included those outcomes that were considered important for the patient and/or their practitioner. We found that the evidence for all these outcomes was of very low certainty, mainly because of high risk of bias, inconsistency and imprecision of RCTs (Table 2).

Table 2 Summary of findings to evaluate the certainty of the evidence, using the GRADE methodology

EuroQol-5D, European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; RCT, randomised controlled trial; s.d., standard deviations.

a. Higher points are better.

b. Blinding of allocation, personnel and/or outcome assessment was not detailed in the publication. Incomplete data are reported.

c. Sample sizes were small (<400).

d. Selective reporting was not evaluated as the protocol was not available.

e. I 2 > 40%.

f. 95% confidence intervals include 0.5 value.

g. HIgher points are worse.

Discussion

We included six RCTs that evaluated the effects of decision aid in adults with depression. These studies were heterogeneous, had small sample sizes and presented with a high risk of bias. When pooling the RCTs, we found benefits in some outcomes such as decisional conflict, patient knowledge and information exchange, but not in clinical outcomes such as depression symptoms or treatment adherence. All of the outcomes included in the Summary of Findings table had very low certainty of evidence.

The interventions used in the six included RCTs fulfilled all the qualifying items from the International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration criteria.Reference Joseph-Williams, Newcombe, Politi, Durand, Sivell and Stacey27 However, there was heterogeneity regarding the type of decision aids used (including leaflets, booklets, cards, DVD, a webpage or artificial intelligence), treatment options in the decision aids and by whom they were administered (physicians, pharmacists, researchers or the patient themselves). This heterogeneity is expected because the use of the decision aids largely depends on context, and has to be adapted according to population needs.Reference Chenel, Mortenson, Guay, Jutai and Auger18 However, the fact that there were not even two studies that used the same decision aid affects the capability of synthesis and interpretation of the pooled results.Reference Anderson, Oliver, Michie, Rehfuess, Noyes and Shemilt43

Regarding the quality of the included RCTs, participants were not blinded because of the intervention's intrinsic nature. This represents an important source of bias as the perception of subjective outcomes could have been influenced.Reference Mustafa44 Additionally, most RCTs used a no-intervention group as the control without placebo. However, using an information-based intervention about treatment options for depression without a decision-making process as a control group in the RCTs would have helped to prevent the complex intervention effects, and ensure that the effects of the decision aid are not explained only by higher attention from a health professional.Reference Foster and Little45

Regarding the effects of decision aid, our pooled estimates suggest no effect in clinical outcomes, as described by a previous review that assessed decision aid in patients with mood disorders and found no effect with depressive symptoms,Reference Samalin, Genty, Boyer, Lopez-Castroman, Abbar and Llorca46 and by another systematic review that assessed decision aid for screening tests and found no effect in treatment adherence.Reference Stacey, Légaré, Lewis, Barry, Bennett and Eden47 These results could be explained by a linear and logical sequence that we propose. First, the decision aid gives the information to the patient about depression and its treatment options, which explains the ‘knowledge’ improvement. Then, the patients are more capable of discussing the disease and their treatment options with the health professional, which explains the ‘information exchange’ improvement. Later, the patient feels capable of making a choice, which explains the decrease in ‘decisional conflict’. After making a choice, the patients receive their treatment and feel satisfied with their decision, which improves the ‘sure of the intention to choose a treatment’, the ‘treatment satisfaction’ and the ‘decision aid satisfaction’. Lastly, it would be expected that all of these achievements are translated into clinical outcomes: a higher treatment adherence and subsequent reduction of depressive symptoms.

However, regarding this last point, other factors could influence clinical outcomes. Adherence could be affected by accessibility to the treatment, the way the patients perceive the effectiveness of the treatment, severity of the disease, etc.Reference Martin-Vasquez48 Additionally, depressive symptoms could be affected by the treatment adherence itself, the adequacy of the chosen treatment for the clinical characteristics of the patient and other psychosocial factors.Reference Demyttenaere and Haddad49 In addition, some methodological issues could explain the results. None of the studies included in the meta-analysis of depressive symptoms, and only one of the three studies included in the meta-analysis of treatment adherence were designed to assess those outcomes, so there could have been a lack of power to find a difference between study groups.

The pooled analysis found no effect of decision aids on treatment adherence (SMD −0.31 to 0.71). This meta-analysis included three RCTs.Reference Aljumah and Hassali37,Reference Loh, Simon, Wills, Kriston, Niebling and Harter39,Reference Simon, Kriston, von Wolff, Buchholz, Vietor and Hecke40 One of themReference Simon, Kriston, von Wolff, Buchholz, Vietor and Hecke40 contradicted the results of the other two, in addition to having the smallest sample size and the highest risk of bias (as a result of attrition bias and small sample size). Thus, a sensitivity analysis removing that RCT found a beneficial effect of decision aids for treatment adherence (SMD 0.50; 95% CI 0.29–0.70). Thus, we cannot exclude a possible positive effect of decision aids on treatment adherence, which has to be assessed in future studies.

On the other hand, we did find beneficial effects in decision-making process outcomes, such as decisional conflict, information exchange and patient knowledge, similar to a previous review.Reference Samalin, Genty, Boyer, Lopez-Castroman, Abbar and Llorca46 These three outcomes are expected for a decision aid designed to facilitate the shared decision-making process. FiveReference Perestelo-Perez, Rivero-Santana, Sanchez-Afonso, Perez-Ramos, Castellano-Fuentes and Sepucha17,Reference Sepucha, Gallagher and Cosenza36–Reference LeBlanc, Herrin, Williams, Inselman, Branda and Shah38,Reference Simon, Kriston, von Wolff, Buchholz, Vietor and Hecke40 out of six RCTs assessed decision aids developed to enhance patients’ involvement in the decision-making process, support their choices, empower them and improve their knowledge about their therapeutic options. Consequently, the decision aid's main objective may determine the outcomes (decision process or clinical outcomes) it will affect. Future studies assessing decision aid clinical outcomes must assess a decision aid specially designed to improve clinical outcomes, such as treatment adherence, depressive symptoms and quality of life.

Altogether, our results suggest that the use of a decision aid in patients with depression may have an effect on knowledge, information and decision-related outcomes. However, its effect on adherence is doubtful, and there seems to be no effect on depressive symptoms. Although we found a very low certainty of the evidence, stakeholders are needed to decide in this regard. Healthcare institutions must consider the costs, acceptability and applicability of this intervention in their context. Additionally, healthcare professionals must consider the balance between desirable and undesirable consequences of the decision aid's application, and acknowledge the patient information and involvement as decisive components for the shared decision-making process,Reference Bouniols, Leclere and Moret50,Reference van der Weijden, Post, Brand, van Veenendaal, Drenthen and van Mierlo51 to make a decision applicable to each particular patient.

Limitations and strengths

Our study included a small number of heterogeneous studies. However, we decided to conduct a meta-analysis to test the hypothesis about the overall effect of decision aid in patients with depression, for a better decision-making process.Reference Anderson, Oliver, Michie, Rehfuess, Noyes and Shemilt43 The certainty of the evidence was very low for all the prioritised outcomes, which demonstrates the need for more well-designed and adequately reported RCTs with higher sample sizes.

On the other hand, this systematic review has important strengths: it followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement and was inscribed in the PROSPERO database. Also, we performed a comprehensive search strategy across multiple databases, without language restriction, and across articles that cited each of the found studies, which allowed us to find all studies reported in previous systematic reviewsReference Samalin, Genty, Boyer, Lopez-Castroman, Abbar and Llorca46,Reference Stacey, Légaré, Lewis, Barry, Bennett and Eden47 and other studies that were not found in these reviews. Lastly, we evaluated the certainty of evidence with the GRADE methodology.

In conclusion, we found six RCTs that evaluated the effects of decision aid in adults with depression. Evidence of very low certainty suggests that decision aids may have benefits in decisional conflict, patient knowledge and information exchange, but not in clinical outcomes (treatment adherence and depression symptoms). More RCTs are needed to adequately assess the effects of decision aids in patients with depression.

Biographies

Christoper A. Alarcon-Ruiz is a student at the Faculty of Human Medicine, Ricardo Palma University, Peru. Jessica Hanae Zafra-Tanaka is a researcher at the CRONICAS Center of Excellence in Chronic Diseases, Cayetano Heredia University, Peru. Mario E. Diaz-Barrera is a member at the SOCEMUNT Scientific Society of Medical Students, National University of Trujillo, Peru. Naysha Becerra-Chauca is a consultant at the Institute for Health Technology Assessment and Research, EsSalud, Peru. Carlos J. Toro-Huamanchumo is a researcher at the Research Unit for Generation and Synthesis Evidence in Health, Saint Ignacio of Loyola University; and director at the Multidisciplinary Research Unit, Avendaño Medical Center, Peru. Josmel Pacheco-Mendoza is a researcher at the Bibliometrics Research Unit, Saint Ignacio of Loyola University, Peru. Alvaro Taype-Rondan is a researcher at the Research Unit for Generation and Synthesis Evidence in Health, Saint Ignacio of Loyola University, Peru. Jhony A. De La Cruz-Vargas is the director at the Institute for Research in Biomedical Sciences, Ricardo Palma University, Peru.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2020.130.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, C.A.A.-R., upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

C.A.A.-R. and J.H.Z.-T. formulated the research question. C.A.A.-R., J.H.Z.-T. and A.T.-R. designed the study. C.A.A.-R. and J.P.-M. developed the research strategy. C.A.A.-R., J.H.Z.-T., M.E.D.-B., N.B.-C. and C.J.T.-H. did the screening and data extraction. C.A.A.-R. and A.T.-P. did the statistical analysis. C.A.A.-R., J.H.Z.-T., A.T.-R. and J.A.D.-V. interpreted the data for the work. C.A.A.-R. drafted the first manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of interest

None.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2020.130.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.