1. Introduction

Nascent proteins are modified and transported to their final destination via the secretory pathway (Figure 1). Both regulated and constitutive transport of these cargo proteins are essential for embryonic development. In fact, a number of human diseases, including congenital malformations and cancers, arise as a result of mutated or abnormal expression of proteins in this pathway (Merte et al., Reference Merte, Jensen, Wright, Sarsfield, Wang, Schekman and Ginty2010; Routledge et al., Reference Routledge, Gupta and Balch2010; Garbes et al., Reference Garbes, Kim and Riess2015; Yehia et al., Reference Yehia, Niazi and Ni2015; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Yue and Wang2017). The transmembrane emp24 domain (TMED) family consists of type I single-pass transmembrane proteins that are found in all eukaryotes. Members of the TMED family have emerged as important regulators of protein transport (Carney & Bowen, Reference Carney and Bowen2004; Dancourt & Barlowe, Reference Dancourt and Barlowe2010; Jerome-Majewska et al., Reference Jerome-Majewska, Achkar, Luo, Lupu and Lacy2010; Zakariyah et al., Reference Zakariyah, Hou, Slim and Jerome-Majewska2012; Viotti, Reference Viotti2016; Wada et al., Reference Wada, Sun-Wada, Kawamura and Yasukawa2016; Hou et al., Reference Hou, Gupta, Beauchamp, Yuan and Jerome-Majewska2017; Hou & Jerome-Majewska, Reference Hou and Jerome-Majewska2018), and although they are found in the early and late secretory pathways (Figure 2), most studies focus on the function of TMED proteins in the early secretory pathway (Figure 2a): the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), the ER–Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC) and the Golgi (Shevchenko et al., Reference Shevchenko, Keller, Scheiffele, Mann and Simons1997; Dominguez et al., Reference Dominguez, Dejgaard and Füllekrug1998; Fullekrug et al., Reference Fullekrug, Suganuma, Tang, Hong, Storrie and Nilsson1999; Jenne et al., Reference Jenne, Frey, Brugger and Wieland2002; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Hasegawa and Schmitt-Ulms2006; Hosaka et al., Reference Hosaka, Watanabe and Yamauchi2007; Blum & Lepier, Reference Blum and Lepier2008; Montesinos et al., Reference Montesinos, Sturm, Langhans, Hillmer, Marcote, Robinson and Aniento2012, Reference Montesinos, Langhans, Sturm, Hillmer, Aniento, Robinson and Marcote2013).

Fig. 1. Summary of the secretory pathway. Transmembrane and secreted proteins are folded in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and transported to the Golgi via COPII-coated vesicles (anterograde trafficking). ER-resident or misfolded proteins are trafficked back to the ER from the Golgi via COPI-coated vesicles (retrograde trafficking). Clathrin-coated vesicles mediate a portion of post-Golgi trafficking. ERGIC = ER–Golgi intermediate compartment.

Fig. 2. TMED proteins in the secretory pathway. (a) TMED dimers and tetramers are packaged into COPII-coated vesicles (pink) and COPI-coated vesicles (blue) and are implicated in anterograde and retrograde transport. (b) A subset of TMED proteins are also found at the plasma membrane, in secretory granules, at the trans-Golgi and in peroxisomes. ER = endoplasmic reticulum; ERGIC = ER–Golgi intermediate compartment; GPCR = G-protein-coupled receptor.

Members of the TMED family are classified into four subfamilies based on sequence homology (Table 1): α, β, γ and δ (Blum et al., Reference Blum, Feick, Puype, Vandekerckhove, Klengel, Nastainczyk and Schulz1996; Strating et al., Reference Strating, Hafmans and Martens2009; Schuiki & Volchuk, Reference Schuiki and Volchuk2012; Pastor-Cantizano et al., Reference Pastor-Cantizano, Montesinos, Bernat-Silvestre, Marcote and Aniento2016). However, as the different TMED subfamilies have expanded independently during evolution, the number of proteins in each subfamily varies by species (Table 1) (Strating et al., Reference Strating, Hafmans and Martens2009). Nonetheless, all TMED family members share a common structural organization (Figure 3): a luminal Golgi-dynamics (GOLD) domain, a luminal coiled-coil domain, a transmembrane domain and a short cytosolic tail (Strating et al., Reference Strating, Hafmans and Martens2009; Nagae et al., Reference Nagae, Hirata, Morita-Matsumoto, Theiler, Fujita, Kinoshita and Yamaguchi2016, Reference Nagae, Liebschner and Yamada2017; Pastor-Cantizano et al., Reference Pastor-Cantizano, Montesinos, Bernat-Silvestre, Marcote and Aniento2016).

Fig. 3. Domain structure of TMED family proteins. TMED proteins have a signal sequence (SS) that enables their translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER); the SS is cleaved following ER translocation. The luminal portion of TMED proteins consists of a coiled-coil domain and a Golgi dynamics (GOLD) domain. The short cytoplasmic tail includes diphenylalanine (FF) and dilysine motifs (KK), which are important for binding to COP proteins.

Table 1. TMED family orthologues across different organisms.

During anterograde and retrograde transport, TMED proteins dimerize and interact with coatomer (COP) protein complexes to facilitate cargo selection and vesicle formation. The GOLD domain, which was expected to be involved in cargo recognition (Anantharaman & Aravind, Reference Anantharaman and Aravind2002), was recently shown to mediate dimerization between TMED proteins (Nagae et al., Reference Nagae, Hirata, Morita-Matsumoto, Theiler, Fujita, Kinoshita and Yamaguchi2016, Reference Nagae, Liebschner and Yamada2017); a function previously ascribed to the coiled-coil domain. The transmembrane domain, which was predicted to mediate interactions with integral membrane proteins in order to regulate ER exit (Fiedler & Rothman, Reference Fiedler and Rothman1997), was more recently shown to interact with lipids and to aid in vesicle budding (Contreras et al., Reference Contreras, Ernst and Haberkant2012; Ernst & Brügger, Reference Ernst and Brügger2014; Aisenbrey et al., Reference Aisenbrey, Kemayo-Koumkoua, Salnikov, Glattard and Bechinger2019). Interactions with COPI and COPII occur via conserved COP binding motifs in the cytoplasmic tail (Figure 3) (Dominguez et al., Reference Dominguez, Dejgaard and Füllekrug1998; Majoul et al., Reference Majoul, Straub, Hell, Duden and Soling2001).

TMED proteins regulate transport of a diverse group of cargo proteins; these are summarized in Tables 2 and 3, respectively, depending on whether direct interaction with TMED proteins has or has not been shown (Anantharaman & Aravind, Reference Anantharaman and Aravind2002; Theiler et al., Reference Theiler, Fujita, Nagae, Yamaguchi, Maeda and Kinoshita2014; Nagae et al., Reference Nagae, Hirata, Morita-Matsumoto, Theiler, Fujita, Kinoshita and Yamaguchi2016, Reference Nagae, Liebschner and Yamada2017). The best-characterized TMED cargo proteins are glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins (Marzioch et al., Reference Marzioch, Henthorn and Herrmann1999; Muniz et al., Reference Muniz, Nuoffer, Hauri and Riezman2000; Takida et al., Reference Takida, Maeda and Kinoshita2008; Bonnon et al., Reference Bonnon, Wendeler, Paccaud and Hauri2010; Castillon et al., Reference Castillon, Aguilera-Romero and Manzano-Lopez2011; Fujita et al., Reference Fujita, Watanabe and Jaensch2011; Theiler et al., Reference Theiler, Fujita, Nagae, Yamaguchi, Maeda and Kinoshita2014; Pastor-Cantizano et al., Reference Pastor-Cantizano, Montesinos, Bernat-Silvestre, Marcote and Aniento2016). However, members of the TMED family also interact with transmembrane and secreted proteins such as Notch and G-protein-coupled receptors, as well as with a number of Wnt ligands (Tables 2 & 3) (Stirling et al., Reference Stirling, Rothblatt, Hosobuchi, Deshaies and Schekman1992; Marzioch et al., Reference Marzioch, Henthorn and Herrmann1999; Wen & Greenwald, Reference Wen and Greenwald1999; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Wang and Reiser2007, Reference Luo, Wang and Reiser2011; Stepanchick & Breitwieser, Reference Stepanchick and Breitwieser2010; Buechling et al., Reference Buechling, Chaudhary, Spirohn, Weiss and Boutros2011; Port et al., Reference Port, Hausmann and Basler2011; Junfeng et al., Reference Junfeng, Ming and Sean2015; Li et al., Reference Li, Wu, Shen, Belenkaya, Ray and Lin2015). In this review, we summarize the growing body of literature indicating requirements for TMED proteins during embryogenesis and their contributions to disease.

Table 2. Cargo interactors of TMED proteins.

a Also interacts with TMED10.

ER = endoplasmic reticulum; n/a = not applicable.

Table 3. Proteins regulated by the TMED family.

a Also regulated by TMED4.

b Also regulated by TMED5.

c Also regulated by TMED10.

d Also regulated by TMED11.

2. TMED proteins and development

Although the TMED family is essential for normal development, with limited functional redundancy (Strating et al., Reference Strating, Bouw, Hafmans and Martens2007, Reference Strating, Hafmans and Martens2009), the specific functions of most TMED proteins are unclear. In this section, we highlight the roles uncovered for TMED proteins during development in a variety of species (summarized in Figure 4). Mutant Tmed alleles are summarized in Table 4.

Fig. 4. TMED family in development. TMED proteins regulate multiple developmental processes in different organisms.

Table 4. Mutant Tmed alleles in various model organisms.

2.1. Caenorhabditis elegans

The Caenorhabditis elegans genome contains at least one representative member of all four TMED subfamily members (WormBase; WS270) (Table 1): there are two genes in the α subfamily (tmed-4 (Y60A3.9) and tmed-12 (T08D2.1)), one gene each in the β subfamily (sel-9 (tmed-2; W02D7.7)) and in the δ subfamily (tmed-10 (F47G9.1)) and three genes in the γ subfamily (tmed-1 (K08E4.6), tmed3 (F57B10.5) and tmed-13 (Y73B6BL.36)). Two tmed2 mutant alleles were first isolated as suppressors of the egg-laying defect associated with hypomorphic alleles of lin-12 (Table 4) (Sundaram & Greenwald, Reference Sundaram and Greenwald1993). Wen and Greenwald isolated five additional tmed2 mutant alleles in a non-complementation screen (Table 4) (Wen & Greenwald, Reference Wen and Greenwald1999) and suggested that all seven sel-9 alleles were antimorphic (dominant negative) and reduced wild-type sel-9 activity. Interestingly, six of these mutations mapped to the GOLD domain and one mutation was predicted to generate a truncated protein lacking the carboxyl region. Furthermore, though RNA interference (RNAi) knockdown of sel-9 and tmed10 did not affect viability, a truncated mutant allele of sel-9 resulted in phenotypes classified as dumpy (Dpy), uncoordinated (Unc), roller (Rol) and defective egg-laying (Wen & Greenwald, Reference Wen and Greenwald1999). Reduced wild-type SEL-9 and TMED-10 activity allowed mutated GLP-1 protein to reach the plasma membrane and resulted in increased activity of mutated LIN-12 or GLP-1. Thus, although null alleles for tmed genes have not yet been examined in C. elegans, the phenotypes associated with mutations in sel-9 suggest a role for this family in quality control during LIN-12/Notch receptor family protein transport. These studies further indicate that the GOLD domain may play an important role in mediating interactions with LIN-12 and GLP-1.

2.2. Drosophila melanogaster

Nine TMED genes have been identified in the Drosophila genome (FlyBase; FB2019_03) (Table 1): two α (p24-2 and éclair), two β (CG9308 and CHOp24), one δ (baiser) and four γ (p24-1, logjam, opossum and CG31787)). Most of these TMED proteins are localized to the ER–Golgi interface (Boltz et al., Reference Boltz, Ellis and Carney2007; Buechling et al., Reference Buechling, Chaudhary, Spirohn, Weiss and Boutros2011; Saleem et al., Reference Saleem, Schwedes and Ellis2012). Logjam (Tmed6, loj), CHOp24 (Tmed2), p24-1(Tmed3), opossum (Tmed5, opm), eclair (Tmed4, eca) and baiser (Tmed10, bai) were expressed at all developmental stages and in adult tissues (Carney & Taylor, Reference Carney and Taylor2003; Boltz et al., Reference Boltz, Ellis and Carney2007; Graveley et al., Reference Graveley, Brooks and Carlson2011). CG31787 and CG9308 were expressed in a sex-dependent pattern and p24-2 was primarily expressed in adult tissues with limited or no expression in pupal and larval tissues, respectively (Boltz et al., Reference Boltz, Ellis and Carney2007). Expression of a subset of Tmed genes during development (Tmed2, Tmed3, Tmed4, Tmed5, Tmed6 and Tmed10) suggests that they may be involved in Drosophila development beginning at the earliest stages of embryogenesis.

Mutations in Drosophila TMED family members (Table 4) and RNAi experiments indicate a role for TMED proteins in reproduction, embryonic patterning, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signalling and WNT signalling (Carney & Taylor, Reference Carney and Taylor2003; Bartoszewski et al., Reference Bartoszewski, Luschnig, Desjeux, Grosshans and Nusslein-Volhard2004; Buechling et al., Reference Buechling, Chaudhary, Spirohn, Weiss and Boutros2011; Port et al., Reference Port, Hausmann and Basler2011; Li et al., Reference Li, Wu, Shen, Belenkaya, Ray and Lin2015). P-element insertions in the 5′-untranslated region or exon 2 of loj, the first coding exon, were shown to result in a loss of loj (Tmed6) RNA. These mutations led to oviposition defects in female Drosophila (Table 4) (Carney & Taylor, Reference Carney and Taylor2003) and revealed a requirement for this protein in the central nervous system and the mature egg. Bartoszewski and colleagues reported mutations in two additional Drosophila family members (Bartoszewski et al., Reference Bartoszewski, Luschnig, Desjeux, Grosshans and Nusslein-Volhard2004). Deletion of a large portion of the coding region of eca (tmed4) or a point mutation leading to a premature stop codon before the carboxyl domain of the protein were phenotypically indistinguishable, indicating that the carboxyl domain is essential for eca function. The group also identified mutants with a splice-site mutation in bai (tmed10), which led to a premature stop codon and a null allele. They showed that eca was required for both TGF signalling and for Wg secretion. eca and bai mutants had reduced survival, and surviving mutants showed fertility defects; similar to loj mutants, males had reduced fertility and females did not lay eggs. In addition, eca and bai genetically interacted and were both required in oocytes for dorsal–ventral patterning of embryos (Table 4) (Bartoszewski et al., Reference Bartoszewski, Luschnig, Desjeux, Grosshans and Nusslein-Volhard2004). This phenotype was specific for maternally deposited TKV, an orthologue of the mammalian TGF-β receptor BMPR1, and downstream of Dorsal, indicating that the two TMED proteins are required for activity of maternally deposited Drosophila BMPR1. Furthermore, although bai mutants phenocopied the temperature-sensitive thick vein phenotype of tkv mutants, it was not clear why reduced levels of TMED proteins blocked signalling by this TGF-β receptor, especially since the TKV protein was still properly localized in these mutants. Altogether, studies in Drosophila indicate that normal levels of tmed proteins are required for morphogenesis and patterning.

Multiple studies support a role for TMED proteins in WNT signalling. In an RNAi screen, eca and CHOp24 were found to be required for Wg transport (Port et al., Reference Port, Hausmann and Basler2011). Knockdown of these two genes resulted in loss of wing margin tissue, retention of Wg in the ER and reduced extracellular Wg. In a similar screen, Buechling et al. found that opm, CHOp24 and p24-1 were required in Wg-producing cells for canonical Wg signalling (Buechling et al., Reference Buechling, Chaudhary, Spirohn, Weiss and Boutros2011). Furthermore, the group showed that maternal deposits of Opm were required for viability and WntD transport. In a more recent RNAi screen, Li et al. identified bai, CHOp24 and eca to be important in Wg-producing cells (Li et al., Reference Li, Wu, Shen, Belenkaya, Ray and Lin2015). All three studies suggest that TMED family members are implicated in the transport of WNT proteins from the ER to the Golgi. Furthermore, eca and bai are required for both TGF and WNT signalling at different developmental stages and in different tissues, suggesting that TMED proteins function in multiple pathways and are regulated both temporally and spatially.

2.3. Xenopus laevis

The Xenopus tmed gene family is composed of nine members (Xenbase) (Table 1): two δ subfamily members (tmed10 and tmed10-like) (Strating et al., Reference Strating, Hafmans and Martens2009), four γ subfamily members (tmed1, tmed5, tmed6 and tmed7), two α subfamily members (tmed4 and tmed9) and one β subfamily member (tmed2). The TMED family is involved in X. laevis pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) protein biosynthesis in melanotrope cells of the intermediate pituitary gland. POMC is a precursor polypeptide that is cleaved to produce multiple peptide hormones. Six of the Tmed proteins (Tmed2, Tmed4, Tmed5, Tmed7, Tmed10 and Tmed10-like) are expressed in melanotrope cells, whereas the other two members (Tmed1 and Tmed9) are not (Rotter et al., Reference Rotter, Kuiper, Bouw and Martens2002). Tmed proteins are generally localized to the Golgi compartment in Xenopus. However, the steady-state subcellular localization shifts towards a subdomain of the ER and ERGIC in biosynthetically active intermediate pituitary melanotrope cells (Kuiper et al., Reference Kuiper, Bouw, Janssen, Rotter, van Herp and Martens2001). Furthermore, Tmed2, Tmed4, Tmed7 and Tmed10-like are upregulated in active melanotropes compared to inactive melanotropes (Rotter et al., Reference Rotter, Kuiper, Bouw and Martens2002).

Tmed proteins co-localize with the major cargo protein POMC and have functionally non-redundant roles in regulating its secretion. For example, transgenic expression of Tmed4 dramatically reduces POMC transport, leading to its accumulation in ER-localized electron-dense structures (Strating et al., Reference Strating, Bouw, Hafmans and Martens2007). By contrast, transgenic expression of Tmed10-like does not induce changes in the cell's internal structure or in POMC secretion, but it does impact Golgi-based processing of POMC (Strating et al., Reference Strating, Bouw, Hafmans and Martens2007). Furthermore, transgenic expression of Tmed4 or Tmed10 disrupted pigmentation in Xenopus because of insufficient POMC secretion or abnormal POMC processing, respectively (Bouw et al., Reference Bouw, Van Huizen, Jansen and Martens2004; Strating et al., Reference Strating, Bouw, Hafmans and Martens2007). The Xenopus POMC studies are critical indications that Tmed4 and Tmed10 can affect different sub-compartments in the early stages of the secretory pathway and can be localized differentially depending on cell type (Kuiper et al., Reference Kuiper, Waterham, Rotter, Bouw and Martens2000). These studies suggest an emerging model where Tmed2, Tmed4, Tmed7 and Tmed10 function together (potentially as a tetramer) to traffic POMC through the early secretory pathway during pigment development. Since POMC neurons are also found in mammals, TMED proteins may play an evolutionarily conserved role in the development of the melanocortin system in humans.

2.4. Mouse/human

There are ten known TMED genes in mammals (Table 1): three α subfamily (Tmed4, Tmed9 and Tmed11), five γ subfamily (Tmed1, Tmed3, Tmed5, Tmed6 and Tmed7), one β subfamily (Tmed2) and one δ subfamily (Tmed10), with an additional non-functional duplicate of Tmed10 found solely in apes and humans (Blum et al., Reference Blum, Feick, Puype, Vandekerckhove, Klengel, Nastainczyk and Schulz1996; Horer et al., Reference Horer, Blum, Feick, Nastainczyk and Schulz1999). Individual TMED proteins appear to be more crucial in mammals during embryonic development when compared to less complex organisms. We generated two mutant mouse lines with mutations in Tmed2; one line carries a single point mutation in the signal sequence of Tmed2 and the second line has a β-galactosidase gene trap inserted in intron 3 of the gene. Both mutations resulted in a loss of TMED2 protein and embryonic lethality by embryonic day (E) 11.5 (mid-gestation) (Table 4) (Jerome-Majewska et al., Reference Jerome-Majewska, Achkar, Luo, Lupu and Lacy2010). Similarly, deletion of exon 1 of mouse Tmed10 results in loss of TMED10 protein and embryonic lethality at E3.5, before implantation (Denzel et al., Reference Denzel, Otto and Girod2000). Thus, TMED2 and TMED10 have non-redundant functions during embryogenesis.

Tmed2 mRNA is expressed in a temporal and a tissue-specific pattern in mice (Jerome-Majewska et al., Reference Jerome-Majewska, Achkar, Luo, Lupu and Lacy2010). At E5.5, Tmed2 is expressed in embryonic and extraembryonic regions. Expression becomes higher in the ectoplacental cone and extraembryonic ectoderm at E6.5. At E7.5, Tmed2 is observed in the ectoplacental cone, amnion, anterior neural folds and head mesoderm. At E8.5, Tmed2 expression is found in the somites, heart and tail bud. Prior to lethality by E11.5, Tmed2 homozygous null mutants are developmentally delayed (beginning at E8.5) and present with an abnormally looped heart (E9.5) and an abnormal tail bud morphology (E9.5–E10.5) (Jerome-Majewska et al., Reference Jerome-Majewska, Achkar, Luo, Lupu and Lacy2010). Therefore, TMED2 is important for morphogenesis of the organs in which it is expressed.

In addition, Tmed2 is essential for the formation of the placenta (Jerome-Majewska et al., Reference Jerome-Majewska, Achkar, Luo, Lupu and Lacy2010). At E8.5, Tmed2 mRNA is expressed in the allantois, chorionic plate and giant cells. At E9.5, Tmed2 continues to be expressed in the giant cells, spongiotrophoblasts and the forming labyrinth layer, but it is no longer expressed in the allantois. At E10.5, Tmed2 expression is similar to E9.5; however, expression in giant cells is restricted to a subset of the layer and expression can be observed in the maternal decidua. In accordance with the expression of Tmed2 in the placenta, E9.5–E10.5 placentas of Tmed2 homozygous mutants fail to form a labyrinth layer, resulting in lethality at mid-gestation, with a subset of embryos failing to undergo chorioallantoic attachment (Jerome-Majewska et al., Reference Jerome-Majewska, Achkar, Luo, Lupu and Lacy2010). TMED2's requirement in the placenta is cell-autonomous in the chorion and non-cell-autonomous in the allantois where it regulates fibronectin and VCAM1 localization during chorioallantoic attachment (Hou & Jerome-Majewska, Reference Hou and Jerome-Majewska2018). These studies indicate a crucial role for TMED2 in the development of the placenta. Furthermore, TMED2 is expressed in the human placental syncytiotrophoblast, cytotrophoblast and stromal cells between the gestational ages of 5.5 and 40 weeks (Zakariyah et al., Reference Zakariyah, Hou, Slim and Jerome-Majewska2012). Thus, TMED2 may also be crucial during human placental development.

TMED10 is expressed in the embryonic mouse brain at E15 and expression declines with age in the developing postnatal brain (Vetrivel et al., Reference Vetrivel, Kodam, Gong, Chen, Parent, Kar and Thinakaran2008). In the rat central nervous system, TMED10 expression is found in the cortex, hippocampus and brainstem at postnatal day (P) 7 and P21 (Vetrivel et al., Reference Vetrivel, Kodam, Gong, Chen, Parent, Kar and Thinakaran2008). TMED10 is also expressed in the developing postnatal sensory epithelium of the murine inner ear at P3, but not at P14 and P30, suggesting that TMED10 may play a role in inner ear development (Darville & Sokolowski, Reference Darville and Sokolowski2018). The role, if any, of TMED10 in the pre- and post-natal development of the mammalian brain and inner ear remains to be identified.

Overall, TMED proteins are expressed in a tissue-dependent, developmental age-dependent and even sex-specific pattern, suggesting non-redundant functions across various species (Rotter et al., Reference Rotter, Kuiper, Bouw and Martens2002; Carney & Taylor, Reference Carney and Taylor2003; Boltz et al., Reference Boltz, Ellis and Carney2007; Jerome-Majewska et al., Reference Jerome-Majewska, Achkar, Luo, Lupu and Lacy2010; Hou et al., Reference Hou, Gupta, Beauchamp, Yuan and Jerome-Majewska2017). The TMED family is implicated in developmental processes such as wing morphogenesis in Drosophila, reproductive system development in C. elegans, embryonic development in rats and mice and placental development in mice and humans (Jerome-Majewska et al., Reference Jerome-Majewska, Achkar, Luo, Lupu and Lacy2010; Buechling et al., Reference Buechling, Chaudhary, Spirohn, Weiss and Boutros2011; Hou & Jerome-Majewska, Reference Hou and Jerome-Majewska2018). Furthermore, the role for TMED5 and TMED10 in regulating WNT and TGF-β signalling, respectively, seems to be evolutionarily conserved in Drosophila and humans (Buechling et al., Reference Buechling, Chaudhary, Spirohn, Weiss and Boutros2011; Port et al., Reference Port, Hausmann and Basler2011). In addition, components of the Notch family of receptors could also be an evolutionarily conserved cargo of the TMED family. Our growing understanding of the involvement of the TMED family in mammalian development paves the foundation for understanding their potential roles in human diseases.

3. TMED proteins and disease

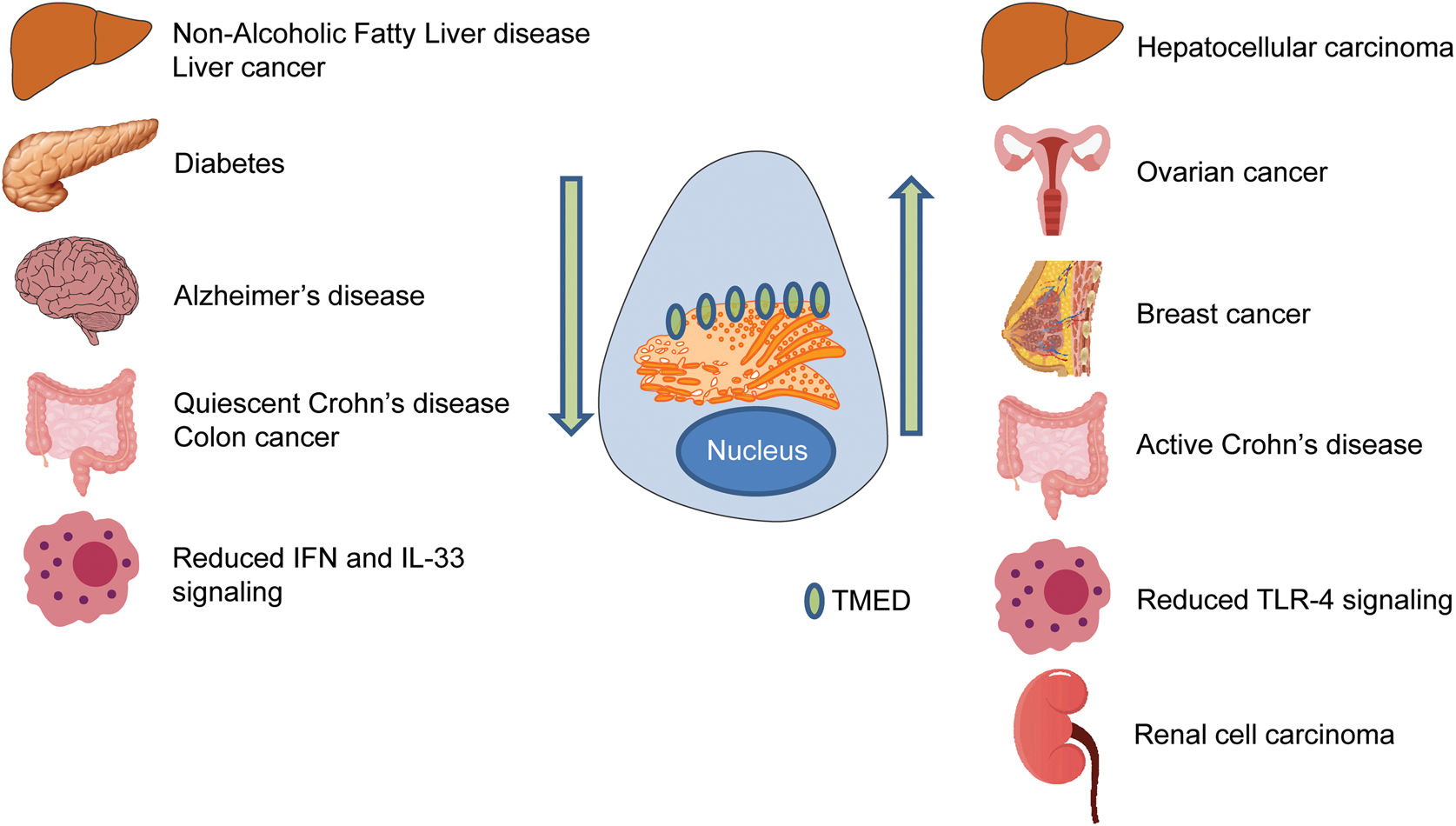

Abnormalities in the controlled transport of proteins in the secretory pathway contribute to diseases such as cancer. More specifically, aberrant expression of TMED proteins is implicated in cancer, liver disease, pancreatic disease and immune system dysregulation. Although these diseases differ greatly in symptom presentation, they reveal the importance of balanced levels of TMED proteins within cells (Figure 5). Excess TMED within the cell can cause a similar phenotype as having too little TMED protein, which makes this family challenging to study.

Fig. 5. TMED family in disease. Disrupted TMED protein levels are associated with a diverse range of diseases. Arrows indicate levels of TMED protein within the cell. Organs represent different diseases associated with TMED proteins. IFN = interferon; TLR = Toll-like receptor.

3.1. TMED proteins and cancer

Current research on TMED proteins suggests an important role in cell proliferation and differentiation, especially with regards to malignancy. TMED2, the sole member of the mammalian β family, displays a cell type-specific role in cancer (Xiong et al., Reference Xiong, Lu and Zhang2010; Shi-peng et al., Reference Shi-peng, Chun-lin and Huan2017). In liver cells, TMED2 is required for normal cell proliferation. The aforementioned homozygous null mouse embryos, with no functional TMED2, were smaller than their littermates prior to death at mid-gestation, suggesting a requirement for TMED2 in normal cell proliferation (Table 4) (Jerome-Majewska et al., Reference Jerome-Majewska, Achkar, Luo, Lupu and Lacy2010). Moreover, heterozygotes were more susceptible to liver cancer compared to their wild-type littermates (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Gupta, Beauchamp, Yuan and Jerome-Majewska2017). Therefore, in liver cells, a reduction in TMED2 results in increased liver tumorigenesis and demonstrates a possible tumour suppressor-like property for TMED2. In contrast, elevated levels of TMED2 were found in ovarian carcinoma patients (Shi-peng et al., Reference Shi-peng, Chun-lin and Huan2017), and ectopic expression of TMED2 in ovarian cancer cells resulted in increased cell proliferation and cell migration, characteristic of metastatic cells. Furthermore, Xiong and colleagues reported that ectopic expression of TMED2 accelerates cell proliferation in murine bone cells, MC3T3-E13 (Xiong et al., Reference Xiong, Lu and Zhang2010). Elevated expression of TMED2 in breast cancer patients was identified as an unfavourable prognostic factor (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Liu, Hu and Hu2019). Thus, depending on cell type, TMED2 may exert either tumour suppressor or oncogenic properties.

Much like TMED2, the role of TMED3 in cancer is cell type-specific. TMED3 expression is upregulated in a number of tumours. TMED3 was identified as a prognostic biomarker of renal cell carcinoma, since higher TMED3 expression levels were found in high-stage and -grade cohorts when compared to low-stage and -grade cohorts (Ha et al., Reference Ha, Moon and Choi2019). TMED3 was also identified as a potential drug target for prostate cancer since it is elevated in patient tumour samples (Vainio et al., Reference Vainio, Mpindi and Kohonen2012). In addition, TMED3 expression is upregulated in human hepatocellular carcinoma tissues. Its expression was highest in metastatic hepatocellular carcinomas when compared to non-metastatic tumours. In cell culture, TMED3 promotes the proliferation, migration and invasion of breast cancer cells, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 (Pei et al., Reference Pei, Zhang, Yang, Wu, Sun, Wang and Wang2019). In fact, TMED3 knockdown inhibited hepatocellular carcinoma cell migration, whereas TMED3 overexpression enhanced cell motility. In liver cells, it is thought to promote metastasis through the IL-11/STAT3 signalling pathway, as both IL-11 and STAT3 phosphorylation levels are elevated in cells overexpressing TMED3 (Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Yang and Han2016).

However, although TMED3 seems oncogenic in hepatocellular carcinomas, renal cell carcinomas, prostate cancers and breast cancers, it appears to have tumour suppressor properties in human colon cancers. In fact, TMED3 was recovered from a genome-wide in vivo screen for metastatic suppressors in human colon cancer (Duquet et al., Reference Duquet, Melotti, Mishra, Malerba, Seth, Conod and Ruiz i Altaba2014). When TMED3 was knocked down in colon cancer cells, TMED9 was upregulated more than twofold. TMED3-mediated WNT signalling is proposed to inhibit metastasis by repressing TMED9. In the same study, loss of TMED3 resulted in increased TMED9 levels and was correlated with increased TGF-β signalling and upregulation of genes with migratory and invasive roles, while also repressing WNT signalling (Mishra et al., Reference Mishra, Bernal, Silvano, Anand and Ruiz i Altaba2019). Thus, similarly to TMED2, the malignant properties of TMED3 are cell type-specific. Although TMED9 has not been investigated in other cancers, in colon cancer it functions as an oncogene.

TMED10 has an important role in limiting TGF-β signalling. TGF-β is a secreted cytokine that modulates cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis, and it is implicated in numerous cancers. TMED10 regulates the dissociation of the TGF-β heteromeric I/II receptor complex. In fact, an isolated small peptide derived from the extracellular domain of TMED10 is sufficient to antagonize TGF-β signalling, which could be used as a therapy for cancers with abnormal TGF-β signalling activity (Nakano et al., Reference Nakano, Tsuchiya and Kako2017).

Our understanding of the contribution of disrupted TMED levels in cancer is in its infancy. However, it appears that their role is tissue- and context-dependent. Since, TMED proteins may promote or inhibit cancer onset and progression, it is important to identify the specific contributions of individual TMED proteins. Intriguingly, TMED proteins may also form regulatory loops to regulate each other's levels during cancer progression.

3.2. Dysregulated immune responses

TMED1 interaction with ST2L, a member of the IL-R family, regulates signalling of IL-33, a proinflammatory cytokine. Following TMED1 knockdown, production of IL-6 and IL-8 – downstream targets of IL-33 – was impaired, indicating that the absence of TMED1 reduced IL-33 signalling. Surprisingly, the interaction between TMED1 and ST2L was found to occur via a protrusion of the GOLD domain of TMED1 into the cytosolic compartment (Connolly et al., Reference Connolly, O'Neill and McGettrick2013).

TMED2 is necessary for cellular interferon (IFN) responses to viral DNA. MITA (mediator of IRF3 activation also known as STING) has a vital role in innate immune responses to cytosolic viral dsDNA. The luminal domain of TMED2 associates with MITA and stabilizes dimerization of MITA following viral infection. Association with MITA facilitates translocation into the ER, as well as anterograde trafficking from the ER to the Golgi. Consequently, suppression or deletion of TMED2 in cells markedly increased titre volume of herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) and led to impaired IFN-1 production upon HSV-1 infection. Moreover, although TMED10 knockdown led to reduced CXCL10 levels, it did not interact directly with MITA and did not disrupt the synergy of TMED2 on cGAS-MITA-mediated activation of an IFN-stimulated response element. Thus, TMED2 is essential for IFN responses to viral DNA, and it is required for the translocation, localization and dimerization of MITA (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Zhang and Jiang2018).

Interestingly, TMED2 was recently reported to play a role in Crohn's disease through the regulation of the dimeric state of AGR2 (anterior gradient 2) (Maurel et al., Reference Maurel, Obacz and Avril2019). Dimeric AGR2 protein acts as a sensor of ER homeostasis. In the presence of ER stress, AGR2 dimers are disrupted and AGR2 monomers are secreted to induce inflammation in the cell. Secreted AGR2 monomers may act as a systemic alarm signal for proinflammatory responses. When TMED2 levels are lower in the cell, partial homeostasis is achieved, resulting in some inflammation from the increase in monomeric AGR2. Thus, low levels of TMED2 are associated with quiescent Crohn's disease as a consequence of fewer AGR2 dimers, causing some inflammation. However, when TMED2 levels are high in the cell, homeostasis is entirely disrupted, resulting in severe acute inflammation (active Crohn's disease). In fact, Crohn's patients with severe acute inflammation had high levels of TMED2 and disrupted autophagy (Maurel et al., Reference Maurel, Obacz and Avril2019). Since the dimeric state of AGR2 is regulated by TMED2, stable levels of TMED2 in the cell may work to suppress inflammatory responses.

TMED7, a member of the γ family, has a critical role in the negative regulation of TLR4 (Toll-like receptor) signalling. Following lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation of human monocytes, TMED7 shows a biphasic increase. Moreover, TMED7 localized mostly in the Golgi and in endosomes, with increased localization to late endosomes following LPS stimulation. Homotypic interaction between TMED7 and TAG disrupts the formation of the TRIF/TRAM complex, inhibiting the MyD88-independent TLR4 signalling pathway. Thus, TMED7 may be a critical inhibitor of TLR4 signalling and innate immune signalling (Doyle et al., Reference Doyle, Husebye, Connolly, Espevik, O'Neill and McGettrick2012).

It is noteworthy that only TMED7 and TMED1 have their GOLD domains in the cytosol (Doyle et al., Reference Doyle, Husebye, Connolly, Espevik, O'Neill and McGettrick2012; Connolly et al., Reference Connolly, O'Neill and McGettrick2013). No other TMED protein has been shown to have a cytosolic GOLD domain, suggesting that this may be a unique feature of these two γ family members.

3.3. Pancreatic disease

An insulinoma is a rare neuroendocrine insulin-secreting tumour derived from pancreatic β cells. Most insulinomas are benign in that they grow exclusively at their site of origin, but a minority metastasize. The aforementioned TMED10 and pancreatic secretory granules study showed that TMED10 is localized to the plasma membrane of pancreatic β cells, where it is involved in the quality control, folding and secretion of insulin molecules (Blum et al., Reference Blum, Feick, Puype, Vandekerckhove, Klengel, Nastainczyk and Schulz1996; Hosaka et al., Reference Hosaka, Watanabe and Yamauchi2007; Zhang & Volchuk, Reference Zhang and Volchuk2010). Knockdown of TMED10 markedly impaired insulin biosynthesis and release; however, the mechanisms by which this occurs are still unclear. In fact, knockdown of TMED10 does not impact total protein levels, suggesting that the effects of TMED10 on insulin biosynthesis are independent of its other secretory pathway functions.

TMED6 has also been implicated in diabetes. Its expression was significantly lower in diabetic rats (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Yang and Jadhao2012), and knockdown of TMED6 in mouse pancreatic Min6 β cells resulted in decreased insulin secretion (Fadista et al., Reference Fadista, Vikman and Laakso2014). TMED6 expression in pancreatic islets of patients with type 2 diabetes was reduced when compared to control islets isolated from healthy patients. Thus, TMED6 seems also to be required for normal pancreatic function and insulin secretion (Fadista et al., Reference Fadista, Vikman and Laakso2014).

3.4. Dementia and Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease is characterized by the extracellular accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides in the brain. Amyloid precursor protein is cleaved by γ-secretases to generate Aβ, which can accumulate into a plaque, causing neurological deficits. In mouse studies, TMED10 expression was widespread throughout the grey matter of the brain, but it was predominantly localized to the presynaptic membranes of neuronal junctions. As amyloid precursor processing enzymes like γ-secretase were also localized to presynaptic membranes, the presence of TMED10 at presynaptic junctions suggests a role in Aβ secretion (Laßek et al., Reference Laßek, Weingarten, Einsfelder, Brendel, Muller and Volknandt2013; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Fujino and Nishimura2015). In addition, TMED10 also suppresses the transport of amyloid precursor proteins through the secretory pathway, resulting in less accumulation of fully processed amyloid precursor protein. TMED9 also reduced Aβ accumulation in the brain (Hasegawa et al., Reference Hasegawa, Liu and Nishimura2010). Therefore, TMED9 and TMED10 might play an important role in preventing Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis in humans (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Hasegawa and Schmitt-Ulms2006; Hasegawa et al., Reference Hasegawa, Liu and Nishimura2010; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Fujino and Nishimura2015).

3.5. Liver disease

Work from our laboratory showed that Tmed2 may play a role in the progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Gupta, Beauchamp, Yuan and Jerome-Majewska2017), which is the major cause of chronic liver disease worldwide (Abd El-Kader & El-Den Ashmawy, Reference Abd El-Kader and El-Den Ashmawy2015). Low TMED2 levels were associated with a corresponding decrease in TMED10 levels. In this novel NAFLD model, TMED2 was not required for activation of the tunicamycin-associated unfolded protein response. However, livers isolated from heterozygous mice had dilated ER membranes and increased levels of eIF2α, suggesting ER stress and activation of the PERK unfolded protein response (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Gupta, Beauchamp, Yuan and Jerome-Majewska2017). Histological studies of mouse livers showed that 28% of heterozygous mice displayed clinical features associated with NAFLD by the age of 6 months.

4. Future directions

Our understanding of TMED proteins in development and disease is in its infancy, and in fact little is known regarding the primate-specific TMED11. These proteins are evolutionarily conserved, and their localization and levels are tightly regulated by the cellular machinery. As discussed, individual TMED proteins are important for morphogenesis, differentiation and homeostasis in a number of organisms (Carney & Taylor, Reference Carney and Taylor2003; Boltz et al., Reference Boltz, Ellis and Carney2007; Vetrivel et al., Reference Vetrivel, Kodam, Gong, Chen, Parent, Kar and Thinakaran2008; Jerome-Majewska et al., Reference Jerome-Majewska, Achkar, Luo, Lupu and Lacy2010; Graveley et al., Reference Graveley, Brooks and Carlson2011; Zakariyah et al., Reference Zakariyah, Hou, Slim and Jerome-Majewska2012; Darville & Sokolowski, Reference Darville and Sokolowski2018). However, although their roles in cargo transport are clearly important and numerous putative cargo proteins are regulated by TMED proteins (Tables 2 & 3), little is understood of the impact of most TMED proteins in development and disease. TMED proteins are found to interact with lipids and with high specificity for specific carbon chain length, begging the question of their contribution to the structure and integrity of the various organelles in which they are found. There are no unifying themes emerging on the requirement, localization or function of TMED proteins in the many organs in which they are expressed. In fact, current data challenge the longstanding notion that TMED proteins are redundant. Thus, it is imperative that individual TMED proteins be studied. In addition, TMED protein oligomerization – a longstanding assumption – is poorly understood and may also be tissue- and temporal-specific. The finding that loss of a TMED protein does not always result in loss of associating members makes a very strong case for studying how TMED proteins interact within different tissues and organisms. Finally, point mutations in the GOLD domain, deletions of large portions of the gene or premature stop codons before the carboxyl domain of TMED proteins all result in loss of function. Thus, it is enticing to speculate that variants found in human TMED genes may directly contribute to the diseases in which they are misregulated.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank members of the Jerome-Majewska lab for comments on the manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by a grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (RGPIN-2015-06699). LAJ-M is a member of the Research Centre of the McGill University Health Centre, which is supported in part by Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec (FRQS).

Conflict of interest

None.