On March 2 and 3, 1859, Pierce Mease Butler of the Butler Plantation estates in the Georgia Sea Islands sold 436 men, women, and children, including 30 babies, to buyers and speculators from New York to Louisiana. It was the largest recorded slave auction in US history, advertised for weeks in newspapers and magazines across the country. The venue was the Savannah Tenbroeck Racetrack, three miles shy of the city. Eager potential buyers filled every hotel in Savannah. The two-day auction netted $303,850 for the debt-ridden Butler, a phenomenal sum. On the eve of the Civil War, this unprecedented sale was noteworthy not only for its size but because Butler Plantation slaves were generally not sold on the open market before; many lived their entire lives on Butler’s estates. Surely, these lives were difficult and burdensome, but together they formed a community with its own norms, values, and customs – often informed by their shared African heritage. Now they were displaced from their “home” and separated from their families. It is for this reason the slaves called the auction “The Weeping Time.”

A new chapter of their families’ stories began after the auction, and then again after Emancipation in 1863, when some of these newly freed slaves set out toward plantations all over the South searching earnestly for their loved ones. It is likely that the only lingering connections to their relatives were memories of their last meeting – on the auction block. They pursued every avenue in search of those whom they had lost. In some very special cases, they found each other. Others remained in the communities of their masters, bought property, worked the land, and built new lives for themselves.

This is their story.1

At exactly 11:55 a.m. on March 3, 1859, Dorcas, chattel number 278, was sold away from her first love, Jeffrey, a twenty-three-year-old “prime cotton hand.” She stood on the auction block motionless – emptied of words, emptied of tears. She spent the greater part of that cold and rainy Thursday morning contemplating their final separation. Now the moment came and she stood as still as a bronze cast, her head covered with a beaded gray shawl. She stared vacantly at the auctioneer who, with one stroke of his gavel, declared a death knell on her future.

“SOLD! Young Negro wench and a family of 4 to the fine gentleman from South Carolina at 11:55 am!” bellowed auctioneer William Walsh, as he pulled out his watch to check the time. He had a grandfatherly look, with a soft, pearl-gray beard that jutted out above his slightly protruding chest. He wore a double-vested black suit with several well-appointed pockets, one of which contained a shiny silver stopwatch that hung from a short chain. Dorcas might have expected a monster of a man, with blood-red eyes and a cold, cobbled face. Then she might have surmised, unreasonably, how a man with one stroke of the gavel and the stop of a watch could separate her from the man she loved.

Jeffrey, a tall, strapping field hand with soft eyes, who was sold earlier for $1,310 to another master, pulled off his hat, dropped to his knees, and wept. Just the day before, he had cherished high hopes. As soon as he was sold to a rice plantation owner of the Great Swamp, he spent the rest of the day begging and pleading with him to purchase Dorcas:

I loves Dorcas, young Mas’r; I loves her well an’ true; she says she loves me, and I know she does; de good Lord knows I loves her better than I loves any one in de wide world – never can love another woman half as well. Please buy Dorcas, Mas’r. We’re be good sarvants to you long as we live. We’re be married right soon, young Mas’r, and de chillun will be healthy and strong, Mas’r, and dey’ll be good sarvants, too. Please buy Dorcas, young Mas’r. We loves each other a heap – do, really true, Mas’r.2

When his new master seemed deaf to his pleas, he came up with another strategy:

“Young Mas’r,” he said in an almost businesslike manner,

Dorcas prime woman – A1 woman, sa. Tall gal, sir; long arms, strong, healthy, and can do a heap of work in a day. She is one of de best rice hands on de whole plantation; worth $1,200 easy, Mas’r, an’ fus’rate bargain at that.3

These words seemed to move his new master, who looked at him obligingly and indicated he would consider his proposal. He approached Dorcas with white-gloved hands and first opened her lips to check her age. He turned her around, as if spinning a top, and bade her take off her turban. As she turned, his white-gloved hand would alternately brush against her back and breasts. He examined her limbs one by one and put his hands around her ample waist. Yes, these hips might be worth something. They might, in fact, breed a few children, all to his profit. He nodded approvingly at Jeffrey and agreed to bid on her the next day, providing the price was right.

This was all the hope that Jeffrey needed. They would be together, he and his Dorcas; they would be far from home and family but at least they would be together. They would be married, and they would create a new family.

But when that hour came, Jeffrey’s master did not comply. Had she been sold alone, he said, he would have raised his paddle for a bid. But Dorcas was not to be sold alone. At the last minute, Mr. Walsh had added her to a family of four to be sold as one lot to a South Carolina plantation. Perhaps it was because she was a rice hand herself (as opposed to a cotton hand like Jeffrey) that she was sold with Chattel no. 277, Eli, a thirty-five-year-old rice hand and his three small children, Celia, Rose, and Eliza (Chattel nos 279–281), ranging in age from six months to ten years. Rice was a premium in South Carolina and experienced rice hands were always in demand.

The thread that connected Jeffrey and Dorcas was undone. Dorcas was led away, and Jeffrey, who by this time was inconsolable, was joined by his friends. They stood in a circle around him expressing no emotion but standing guard of his.

Dorcas and Jeffrey were not the first slaves up for bid on those fateful days of March 2 and 3, 1859; George, Sue, and their young children, George and Harry, held that distinction. Cotton and rice planters respectively, each member of the family was originally sold for $600 each, but the buyer did not take the family that first day because of a dispute about the bidding process. As such, although George and his family were the first up to bid, their fate was not settled until the second day of the sale, when they were bought for $620 each, for a grand total of $2,480.4

Chattels

1. George, age 27, 1832, Prime Cotton Planter

2. Sue, age 26, 1833, Prime Rice Planter

3. George Jr., age 4, 1855, Boy Child

4. Harry, age 2, 1857, Boy Child

How did these slaves end up in this smoke-filled stable? All their lives, they heard it said about the Butler Island Negroes:

“We’re Geechees. We don’t get sold up river like no common cattle.” Overseer Roswell King Jr. reiterated this in his boasts that Butler Island negroes weren’t bought and sold like slaves on the mainland plantations. “And there isn’t a dirt eater among them,” he declared, meaning that they were well fed and housed by their masters.5 Even the mainland residents of Darien who came to market would comment that the Butler negroes were a race apart. In fact, many noted that they had their own dialect that only they could understand, and it was not until after the Civil war that they mixed with other black populations in the area.

None of the Butler slaves have ever been sold before, but have been on these two plantations since they were born. Here they have lived their humble lives, and loved their simple loves; here were they born and here have many of them had children born unto them; here had their parents lived before them, and now are resting in quiet graves on old plantations that these unhappy ones are to see no more forever;6

Such was the account of a certain reporter, Mortimer Thomson, nicknamed “Doesticks,” who was disguised as a buyer at the two-day auction. Doesticks was a man of the North and a writer for the New York Tribune who, during the auction, mingled among the buyers while carefully hiding his abolitionist sympathies. He recorded every word of their conversations with interest; no doubt with the intent to show how cruel an institution slavery indeed was.

Just as their parents and grandparents before them, the Butler slaves made Butler Island and St. Simon’s their home. Now they would have to leave it behind – relatives resting in gravesites on the estates and a thousand memories in the place they called home.

Butler Island Plantation and the St. Simon’s estate called Hampton Point had been in the Butler family for over four generations. Located off the coast of Georgia, between the Altamaha River and the Atlantic Ocean, these islands were worlds to themselves. The river, as the slaves liked to say, was like a prison wall. Only the slave boatmen, who skillfully navigated its many twists and bends, viewed the river differently. The field hands were obliged to work in gangs according to tasks. The overseers and the slave drivers watched their every move. But these boatmen who carried goods, people, and produce on their hand-carved canoes from the islands to the mainland enjoyed a semblance of freedom.7 If the slaves were prisoners, they were prisoners of hope whose songs of freedom heralded a better time to come.

Many a day they could be heard singing the hymn: “I want to climb up Jacob’s ladder,” or even the more subversive freedom song:

With the wind at their backs, how they dared to sing songs of freedom in a land of slavery; how they dared to sing of Haiti who had fought for its freedom in 1791. The boatmen and other slaves likely heard about the Haitian revolution from none other than the Butlers themselves and their slave-owning neighbors. Those were days filled with fear and anxiety about the possibility that such an uprising could take place in their backyard.9

Major Pierce Butler, the patriarch who came from South Carolina by way of Ireland, was the master of Butler Island at the time. He was famous for having been one of the signers of the United States Constitution. Since 1774, he had made a fortune cultivating rice along the marshy shores of the Altamaha Delta on the Butler estate and growing thousands of acres of Sea Island cotton on St. Simon’s island.

He had a reputation for being controlling and curiously cut his own children out of his will but left all of his properties to his grandsons Pierce Mease and John. As a result, Pierce Mease Butler lived a very comfortable life in an expensive town home in Philadelphia. He ran his plantation estates from afar through overseers who, in turn, employed a number of slave drivers. But Pierce Mease Butler, who inherited the Butler plantation estate with his brother John, was careless with his finances. His divorce in 1848 from the famed Shakespearean actress Fanny Kemble was costly and, moreover, he gambled much of his inheritance away.10

Slaves were long used to pay off the debts of their masters. If a master lost a wager in a poker game, his slaves would go to the winner. If he defaulted on a bank loan, slaves would be added to the bank’s balance sheet. It was also not unusual for them to be given as wedding gifts or for individual family members to be willed to different parties. In 1859, this was not a new practice.11

The auction was years in the making. Butler’s 440 slaves – his half of his grandfather’s inheritance – had to be sold because, by 1856, Butler had gambled away much of his fortune on the stock market.12 His grand home in the heart of Philadelphia was to be sold in lots and his “hereditary negroes” were to be sold on the auction block. The stock market crash of 1857 that caused a run on many of the major banks only served to worsen his situation. As his friend George Fisher lamented at the time, this crisis may not have happened had people not been so reckless:

A prudent people will make prudent banks. A wild and reckless people will make rash and headlong banks, and we are a wild and reckless people. We like to make money fast, because the circumstances of the country tempt us to make money fast by offering unprecedented facilities for doing so. This creates a demand for capital beyond the supply and therefore fictitious capital is created. So long as confidence is maintained, all is well, but a failure at length must occur and then the fiction becomes apparent.13

Here, he very well could have been describing the dapper Pierce Mease Butler, whose “hereditary fortune of $700,000 (was) lost by sheer folly and infactuation ... Such is the end of folly.”14

By 1856, Butler’s situation worsened to the degree that Tom James and Henry and George Cadwalader of Philadelphia were appointed trustees over his estate and that of Gabriella Butler, the wife of his deceased brother, John Butler.15 Along with Butler, they decide to sell his half of the plantation slaves, pay off his debts, and regain a large income.

On February 16, 1859, Trustee Thomas C. James was authorized by Gabriella Butler, the widow of Pierce’s brother John, to represent her in the “agreement made the following day appointing Thomas M. Foreman, James Hamilton Couper and Thomas Pinckney Huger to appraise and divide the slaves.” This appraisal only listed those slaves as Share A, who were to remain on the plantation as part of Butler estate.16 Slaves like Frank, the driver, and his wife Betty were at the top of the list of those who would remain on the estate. Frank was listed as age 61 and, under the REMARKS category, he was said to be “bedridden superannuated.” Betty, his wife, was listed as 58 years old and, under REMARKS, was listed as a “poultry minder.” She was valued at $100 but there was ironically no value listed for Frank, who was once second only to the overseer in terms of authority on the plantation. This is likely because he was now 61, sick and bedridden, well past his usefulness to the Butlers or anyone else.17

The other 440 were to be sold on March 2 and 3.

In the same month, Joseph Bryan, a well-known slave dealer and former serviceman and chief of police of Savannah was commissioned to manage this major slave sale. Savannah was the perfect choice because of its proximity to the Butler estate in Darien County as well as the fact that it was one of the South’s largest centers for the trade in slaves.18 Bryan was one of the largest slave brokers in the South, with both an office and a slave pen on the corner of Johnson Square. He was a highly regarded US Navy veteran and city official. Upon his death, The Savannah Republican would record: “He was one whom a large number of the young selected as their guide and example in life.”

In the early months of 1859, Bryan anticipated this slave sale to be a major boon to his business. He was not to be disappointed. Records show that he made a handsome sum of $8,000 in commissions on the sale. His slave pen was located next to the site that was eventually to be the location of the First African Baptist Church, founded by George Leile, Savannah’s oldest black church and said to be the oldest black church in North America (and eventually pastored by an ex-slave preacher named Andrew Bryan19). The slave-holding pen itself later became a schoolhouse after the Civil War, a black underground school called the Savannah Educational Association. All that remains today is “418 Bryan St.” marked above the door and the remains of a two-story building whose decrepit walls alone know the whole story of the shattered lives that passed through those doors.

In 1859, Bryan’s slave mart was thriving. He put ads in papers all over the country announcing the sale in The Savannah Republican, The Savannah Daily Morning News, The Charleston Courier, Christian Index, Albany Patriot, Augusta Constitutionalist, Mobile Register, New Orleans Picayune, Memphis Appeal, Vicksburg Southern and the Richmond Whig, announcing:

FOR SALE

Long Cotton and Rice Negroes!

A gang of 440

Accustomed to the culture of Rice and Provisions, among them are a no of good mechanics and house servants

Will be sold on 2nd and 3rd day of March at Savannah

by J Bryan

SALE OF 440 NEGROES!

Persons desiring to inspect these Negroes will find

Them at the Tenbroeck Race Course20

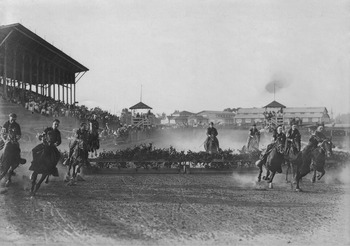

It was to this race course, surrounded by dense woods, just three miles shy of Savannah, that all of Pierce Butler’s slaves were taken. From the late eighteenth century, this racetrack was said to be one of the finest of its kind and was host to the Savannah Jockey Club’s racing season from 1857 onwards. The mile-long track with its “fineinclosure (sic), halls, stables for other large gatherings” was one of the playgrounds of Savannah’s elite.21

Figure 1.1 Savannah’s Tenbroeck Racetrack, site of the largest slave auction in US history.

But on this sad occasion, it housed those on the opposite end of the spectrum: those without property, much less horses; those who were considered property themselves and treated no better than the animals whose sheds they temporarily occupied. Most of the slaves arrived at the racetrack via railroad cars from the Darien town center on the coast that was minutes from the Butler estate. Some also traveled by steamboat.

They were herded into sheds that normally housed the horses and the carriages of the gentlemen attending the races. In the continuous, pouring rain in the days before the sale, broker after broker, speculator after speculator arrived at the race course to examine and inspect the slaves. The buyers paraded them and made them dance. They opened their clothing to check for wounds; they pinched their limbs and flexed their muscles. They searched earnestly for scars, since scars were said to be evidence of a rebellious nature. When they finished their inspections, they posed questions regarding their abilities and their willingness to work. They were to be sold in families in the narrowest sense of the word: married couples and mothers and young children, not brothers or sisters or older parents.22

They were the talk of Savannah that spring of 1859. Negro buyers and brokers, slave breakers and drivers from North and South Carolina, Virginia, Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana eagerly came to put in their bids. The office of Joseph Bryan, the Negro broker who superintended the sale, was flooded with inquiries from those in other parts of the country who could not come but wanted to send proxies to ensure that their bids would be considered.

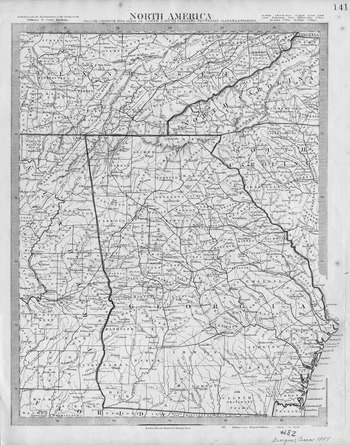

Figure 1.2 Gullah Geechee region.

The buyers were a rowdy lot. They were like a group of hard-playing, top-of-the-lungs-swearing poker players in a smoke-filled game. The best-dressed “fine” Southern gentlemen with long white gloves mixed amongst these hard-nosed and often unkempt Negro buyers, who attended at least two auctions a week and were as callous as their business. They did not stand on ceremony or assume any of the genteel etiquette associated with the Old South. They did not wear suits and jackets, and instead ambled around the market in their shirtsleeves in tall, weather-beaten leather boots. At a glance, they looked like hunters, and of course they were hunters of a sort: of the human species.23

But it was business, just business, and many of the buyers jostled with one another at numerous auctions. They swore and carried on like sailors on a slave ship. A thick gray smoke emanating from their continually lit pipes wafted through the long room adjoining the race course that was appointed for the sale. Now and again, one could hear them almost groan with delight at the prospect of purchasing a nice Negro wench for their more upscale clients.

“Well, Colonel, I seen you looking sharp at Shoemaker Bill’s Sally. Going to buy her?”

“Well, Major, I think not. Sally’s a good, big, strapping gal, and can do a heap o’work; but it’s five years since she had any children. She’s done breeding, I reckon.”24

Just then, Anson and Violet, a couple who looked older than their fifty years, Chattel nos 111 and 112, were brought to the stage. Each carried a bundle under their arms that seemed almost to dwarf their small, tender frames. Violet’s hair was silver-gray but Anson’s was salt and pepper. Both were infirm. Violet had an irrepressible cough and Anson was listed in the catalog as “ruptured and as having one eye.” Their deeply lined faces told their own stories – much like the stories they and others told on the Butler plantation. In the legend of the Butler slaves who could fly, for example, brave slaves walked into the waters to their death rather than face a life under the lash. They flew back to Africa, the old folks said; they flew away and now they were free.25 Maybe those tales were of some comfort now. Maybe only those stories – the idea that there would be freedom someday, even if only in death – kept them from falling onto that stage in the face of the raucous taunts of the buyers and brokers.

“250 going once, going twice; SOLD! To the good man from Georgia,” said Walsh scarcely containing his laughter as Anson and Violet were led off the stage.

“Cheap gal, that, Major!” said one of the buyers to another.

“Don’t think so. They may talk about her being sick; it’s no easy sickness she’s got. She’s got consumption, and the man that buys her will have to be a doctrin’ her all the time, and she’ll die in less than three months. I won’t have anything to do with her – don’t want any half dead niggers about me.”26

For their part, Anson and Violet stepped down from the stage without even looking in the direction of their new owner. At the last moment, Anson might have turned a glance at the jeering crowd, his well-worn eyes concealing his anger and his pain. Like many a slave spouse before and after him, he had probably learned the art of self-restraint.27 He had learned to bite his tongue in order to save his family from certain death. He, himself, could take the taunts and ridicule of the crowd, but he could not protect the wife he loved. He could not protect her on the plantation from the overseer’s lash, he could not protect her from sexual abuse, nor could he protect her on the auction block from this open scorn. A quiet sense of misplaced shame likely hovered above him as he descended the stage.28

The next group up for sale, however, reacted altogether differently.

Chattels

99. John, aged 31, prime rice hand

100. Betsey, aged 29, rice hand, unsound

101. Kate, aged 6

102. Violet, aged 3 months

Chattel nos 99–102 (John and Betsey, husband and wife, holding their two children – Kate, six years old, and baby Violet, three months old), from the beginning, struck a decidedly defiant pose. Betsey, in particular, a young twenty-nine-year-old rice hand, who was barely four feet tall with old woman hands, was the kind of woman who was not going to go complacently. She was long known for having a fiery temper, perhaps the reason she was listed in the catalog as “unsound.”29 Rebellious slave women who defied their masters were often called unsound. Those were the women who attempted to poison their slave owners at dinnertime or who feigned mental or physical illness to deprive them of their labor. In their own way, they were fearsome and commanded a certain respect from slave and free alike.30

Now here stood this “unsound” Betsey before her would be buyers – belligerent and unafraid. She stared into their eyes. With one look, she indicted them. Indicted them for their cruelty, indicted them for their indifference. When she and her family were finally sold to a Mr. Archibald W. Baird of Louisiana for $510 apiece, her determination was even more evident. She would not let them see her cry. The slaves were already calling these fateful days “the weeping time,” but her tears would not flow. She and her husband John and their children, named after their respective mothers, would turn their backs and walk to the stalls in quietude and dignity.

Chattel nos 138–143 should have been up next to bid, since they were listed in the auction catalog, but their lots were withdrawn.

138. Doctor George, age 39, born 1820.

139. Margaret, age 38, born 1821

140. Maria, age 11, born 1848

141. Lena, age 6, born 1853

142. Mary Ann, age 3, born 1856

143. Infant, boy, born February 16, 1859

Apparently through circumstances that could not be fully ascertained, Margaret’s baby, having been born on February 16, was only four days old at the time that the slaves were to begin their long, arduous journey from Butler Island to the point of sale in Savannah. As such, she asked Mr. Butler if she and her family could remain on the plantation and Mr. Butler surprisingly “uttered no reproach,” even though he stood to lose the handsome sum of $4000 – their value on the auction block since they were a family of six.31

Unfortunately, though the circumstances were similar, there was to be no such reprieve for Primus, Chattel no. 72, and Daphney, Chattel no. 73, and their young children, Dido, Chattel no. 74, a girl of three years, and a baby, Chattel no. 75, only one month old, that Daphney was holding protectively in her arms beneath a large shawl. This simple act of maternal love provoked the most boisterous remarks:

“What do you keep your nigger covered up for? Pull off her blanket.”

“What’s the matter with that gal?” said another. “Has she got a headache?”

“Who’s going to bid on that nigger if you keep her covered up?” asked still another without any regard for her newborn that had been born on Valentine’s Day. “Let’s see her face!”32

Auctioneer Walsh had to repeatedly assure the boisterous buyers that there was no attempt at subterfuge: she was not an ill slave that they were trying to palm off as a healthy one but that Daphney had given birth only fifteen days before. For that, she was entitled to the “slight indulgence” of a shawl to wrap around her and her newborn baby to ward off the cold and the rain. With these assurances made, the bidding began and in the end, Primus, who was a plantation carpenter, and Daphney, a rice hand, were both sold for $635. Their two small children, including the infant born on Valentine’s Day, were also sold for the sum of $635 each.33

As the day progressed, other slaves were sold, including brothers Noble and James, Chattel nos 256 and 260, who were sold with their families for the sum of $1,236 each.

Chattels

255. Sally Walker, age 44, born 1815, Cotton Hand, $1,236

256. Noble, age 22, born 1837, Cotton, Prime Man, $1,236

257. Sophy, age 20, born 1839, Cotton, Prime Woman, $1,236

258. Malsey, age 17, born 1842, Cotton, Prime Young Woman, $1,236

259. Chaney, age 13, born 1846, Cotton, Prime Girl, $1,236

260. James, age 9, born 1850, $1,236

Wiseman, age nineteen, described as a prime cotton hand, was also sold with his family, as was the family of Ned and Lena (also known as Scena) – Chattel nos 127 and 128 – who had seven children: Bess, Mary, Flanders, Molsie, Hannah, Thomas, and Ezekiel. Little Brister, at age 5, son of Matty, a twenty-seven-year-old rice hand described as in her prime, was among the many young people sold; he and his mother were sold for $855 each.34

Chattels

225. Kit, age 38, born 1821

226. Matilda, age 38, born 1821

227. Wiseman, age 19, born 1840

228. Hannah, age 12, born 1847

229. William, age 11, born 1848

230. Matilda, age 6, born 1853

231. Kit, age 1, born 1858

Chattels

127. Ned, age 56, born 1803

128. Lena, age 50, born 1809

209. Matty, age 27, born 1832

211. Brister, age 5, born 185435

“Gentlemen!” called out Mr. Walsh. “This is a good time for a break. I encourage you to see the attractions of our bar to your right. May I also remind you of the terms of the sale for when you return:

“One-third cash, the remainder payable in two equal annual installments, bearing interest from the day of sale, to be secured by approved mortgage and personal security, or approved acceptances in Savannah, Ga., or Charleston, S. C. Purchasers to pay for papers,” he said all in one breath.

“As a reminder, we have carpenters, mechanics, we have blacksmiths, we have shoemakers, we have coopers – and prime, prime rice and cotton hands ... Pure blooded negroes ...”36

Indeed, there were many skilled tradesmen, like Joe and his son Robert, Chattel nos 9 and 15, who were considered prime plantation carpenters. Robert was the product of Joe’s first marriage to a slave called Psyche, sometimes known as Sack, who died years before the auction. In many cases, a certain trade had become like the family business – a skill that was passed from father to son. In the best of times, this skill could earn a slave and his family a little extra money, but in the worst of times, such as these, it meant fetching a higher price and even the possibility of being separated from one’s family if it suited either buyer or seller.

With that, the Negro buyers, speculators as they were called at the time retreated to the bar, puffing away on their cigars and cigarettes. The room was putrid with smoke. They ordered their drinks and gathered together in small parties of four and five. Some were eyeing the auction catalogue, looking at the next slaves who were up for bid.37

Chattels

103. Wooster, age 45, hand, and fair mason.

104. Mary, age 40, cotton hand.

105. Commodore Bob, aged, rice hand.

106. Kate, aged, cotton.

107. Linda, age 19, cotton, prime young woman.

108. Joe, age 13, rice, prime boy.

109. Bob, age 30, rice.

110. Mary, age 25, rice, prime woman.

120. Pompey, Jr., age 10, prime boy.

121. John, age 7.

Others were heartily engaged in conversation about the best methods to control a “refractory nigger.” All the while, Doesticks, the reporter in disguise, was recording their conversation. He overheard them discussing all the known methods, with agreement that the crack of a whip and the brand of an iron were most effective. As for pure-blooded negroes, they were much to be preferred to mulattoes with a little white blood.

“A little white blood and they don’t respond to the lash in the same way ...” one hoary-voiced slave driver said above the din of voices.

Others engaged in more political discussions. The year, after all, was 1859 and tensions were rising to a boiling point between North and South. The reopening of the Atlantic slave trade was a subject foremost on their minds. Doesticks reported as much:

The discussion of the reopening of the slave trade was commenced and the opinion seemed to generally prevail that its reestablishment is a consummation devoutly to be wished, and one red faced Major or General or Corporal clenched his remarks with the emphatic assertion that “We’ll have all the niggers in Africa over here in 3 years – we won’t leave enough for seed.38

Meanwhile, Dembo, age twenty, and Frances, age nineteen, Chattel nos 322 and 404, were eagerly awaiting their turn at the hammer. They stood huddled together with their small bundles of cloth and tin gourds – all the possessions they owned in the world. They were eager for the sale to resume for one reason only. They hoped to bring a little plan of their own to fruition.

The night before, they had found a minister among those attending the sale. They begged him to join them in holy matrimony. As a result, they would now be sold as one lot if all went as planned.39

Mr. Walsh called Dembo and Frances to the stage. With a little help from a few of the more boisterous buyers, he then proceeded to poke fun at the couple.

An Alabama buyer with an exposed revolver at his side came up to examine Frances. He did not use white gloves. With his bare hands, cracked with dirt, he checked her teeth, hips, and other assets. Frances looked straight ahead. She displayed no emotion, no embarrassment, and no anger. She kept her focus on their little plan and, within moments, a deal was struck. Dembo and Frances were sold together for $1,320 apiece.

And off they went, smiling broadly. They could hardly contain their joy. They would build a life together on a cotton plantation in Alabama.

But there was to be no such ending for Jeffrey and Dorcas. Jeffrey was going to North Carolina and Dorcas to South Carolina. When last seen, Jeffrey was sitting alone on the ground, crying into his hands, as Dorcas was led away by her new master. She sat in the back of his carriage – emptied of words, emptied of tears.

At the end of the auction, as the final separations were taking place, the New York Tribune correspondent witnessed the following scene:

Leaving the Race buildings, where the scenes we have described took place, a crowd of negroes were seen gathered eagerly about a white man. That man was Pierce M. Butler, of the free City of Philadelphia, who was solacing the wounded hearts of the people he had sold from their firesides and their homes, by doling out to them small change at the rate of a dollar a-head. To every negro he had sold, who presented his claim for the paltry pittance, he gave the munificent stipend of one whole dollar, in specie; he being provided with two canvas bags of 25 cent pieces, fresh from the mint, to give an additional glitter to his generosity.40

It was still raining violently, as if the sky was both weeping and protesting the day’s proceedings.