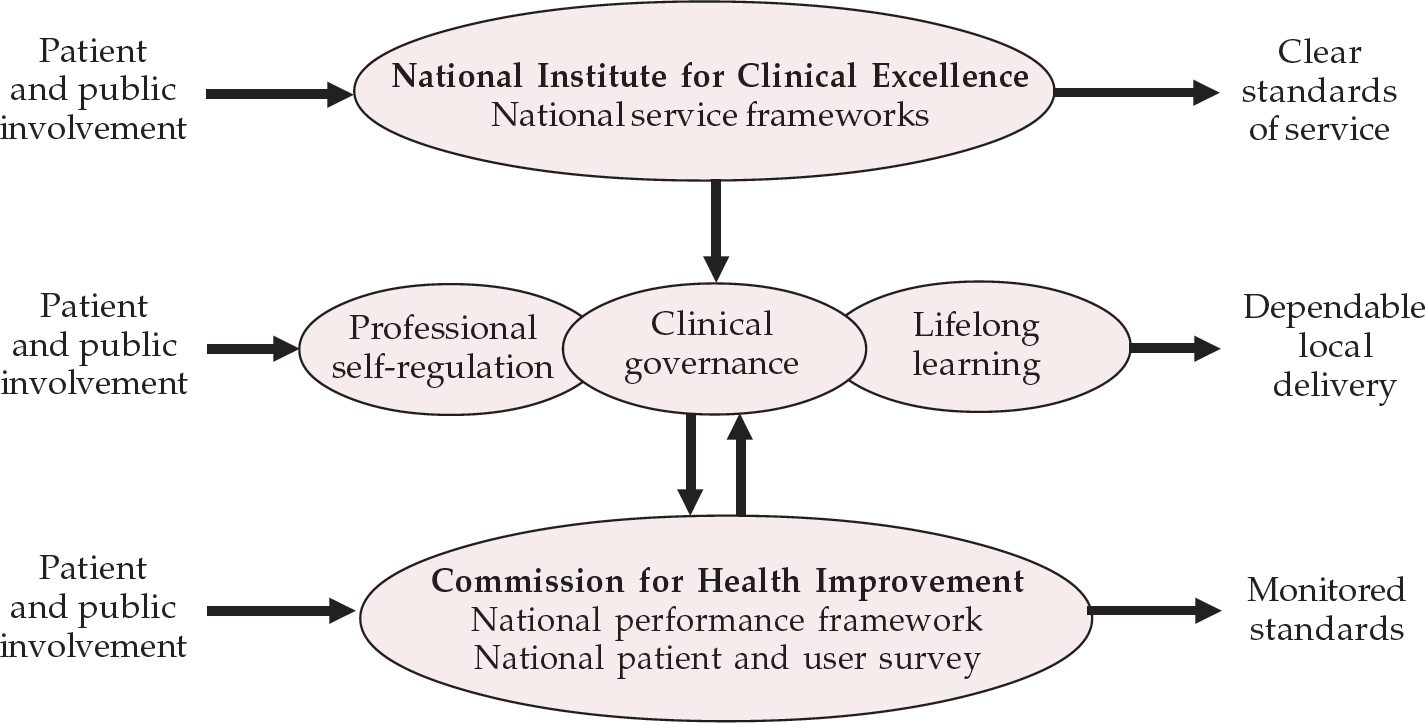

The Government's approach to improving quality in the National Health Service (NHS) was made explicit in a 1997 White Paper and subsequent document (Department of Health, 1997, 1998). Standards were to be set at a national level through the creation of ‘national service frameworks’ and the establishment of the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE; Rawlins, 1999). However, it was recognised that implementation of the emerging guidance would be achieved only if responsibility was taken at local level. Therefore, renewed emphasis was placed on establishing effective professional self-regulation and continuing professional development. Managerial commitment to quality improvement was sought through the development of clinical governance. The effectiveness of these approaches was to be monitored through a number of mechanisms, including a new Commission for Health Improvement, working within a ‘national performance framework’ (Fig. 1). This paper describes the role of NICE and its relevance to psychiatry.

What is NICE?

The National Institute for Clinical Excellence is a special health authority established on the 1 April 1999. Its role is to provide national guidance on the clinical and cost-effectiveness of clinical interventions. It will achieve this through appraising new and existing technologies, developing clinical guidelines and supporting clinical audit. Details of its activities are available on its website (www.nice.org.uk). Its specific advice will be incorporated into the broader organisational standards set by the national service frameworks. It is a small organisation (28 employees) and undertakes its work by commissioning reports from and liaising with a range of professional, specialist and patient organisations. It is supported by its Partner's Council (which includes representatives from all the Royal Colleges) and a series of advisory committees, and has formal links with a number of universities and the National Research and Development Programme. It works closely with local trusts and clinical governance professionals to ensure support for those responsible for implementing its guidance. This includes providing audit advice.

The NICE approach

The details of NICE's main work programmes for 1999/2000 may be found on its website.

Appraising health technologies

The Department of Health and the National Assembly for Wales select technologies for appraisal by NICE based on the following criteria.

-

• Is the technology likely to result in a significant health benefit, taken across the NHS as a whole, if given to all patients for whom it is indicated?

-

• Is the technology likely to have a significant impact on other health-related government policies (e.g. reduction in health inequalities)?

-

• Is the technology likely to have a significant impact on NHS resources (financial or other) if given to all patients for whom it is indicated?

-

• Is NICE likely to be able to add value by issuing national guidance? For instance, in the absence of such guidance is there likely to be significant controversy over the interpretation or significance of the available evidence on clinical and cost-effectiveness?

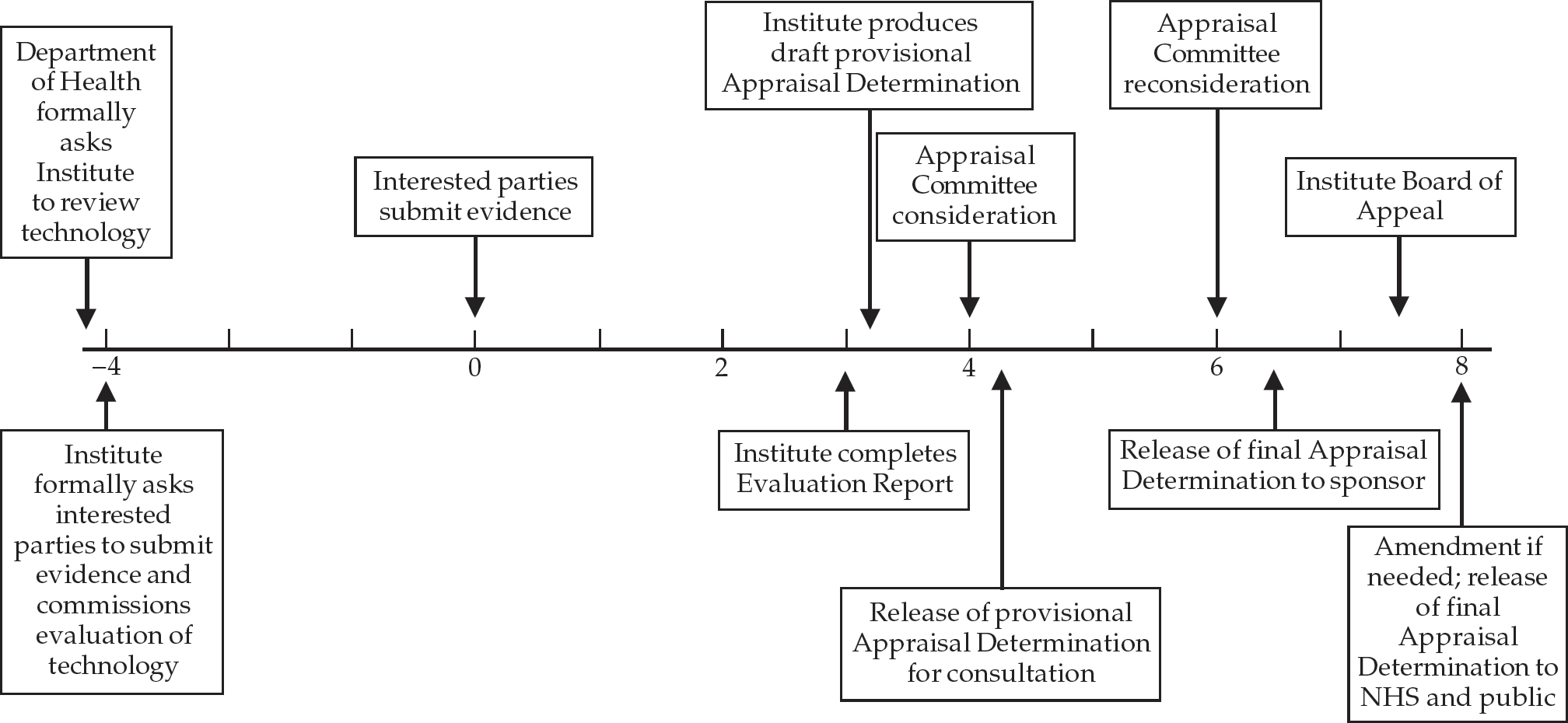

NICE follows a transparent and structured process for its appraisals (outlined in Fig. 2), giving appropriate interested parties the opportunity to submit evidence, comment on draft conclusions and appeal to a panel independent of those involved in the original judgement. Appeals are accepted in cases where NICE is alleged to have failed to act fairly, exceeded its powers or acted perversely in the light of the evidence submitted. This is a dynamic process and is currently being reviewed after the experiences of the first appraisals.

NICE's function in relation to appraisals, as set out in the Secretary of State's directions, is Òto appraise the clinical benefits and the costs of such healthcare interventions and to make recommendations”. It assesses the evidence of all the clinical and other health-related benefits of an intervention (taking this in its widest sense to include such factors as impact on quality and likely length of life, and relief of pain or disability) to estimate the associated costs and to reach a judgement on whether, on balance, this intervention can be recommended as a cost-effective use of NHS resources (in general or for specific indications, subgroups, and so on). Where there is already a cost-effective intervention for the condition, the appraisal should evaluate the net impact on both benefits and costs of the new intervention relative to this benchmark.

NICE must also ensure that, in carrying out its statutory functions, it is sympathetic to the longer-term interests of the NHS, by encouraging innovation.

Evaluation documentation is prepared by the Appraisals Secretariat or commissioned from expert groups (working closely with the Health Technology Assessment arm of the National Research and Development Programme). An Appraisal Committee (Box 1) carries out the appraisals.

Box 1. The Appraisal Committee

Chairperson: Professor David Barnett

-

• Vice chair (1)

-

• Health economists (3)

-

• Health managers (3)

-

• Patient advocates (2)

-

• General practitioners (2)

-

• Hospital physicians (2)

-

• Hospital nurse (1)

-

• Community nurse (1)

-

• Pharmaceutical physician (1)

-

• Public health physician (1)

-

• Surgeon (1)

-

• Diagnostic pathologist (1)

-

• Pharmacist (1)

-

• Biostatistician (1)

Membership

Additional ad hoc members may be appointed ‘for the day’ by the chair, vice chair or chief executive

NICE produces guidance to commissioners and clinicians on the appropriate use of the intervention alongside of current best practice. This guidance covers:

-

• an assessment of whether the intervention can be recommended as clinically effective and as a cost-effective use of NHS resources, either in general or in particular circumstances (for example, for first or second line treatment, particular subgroups, routine use, or in the context of targeted research);

-

• where appropriate, any priorities for treatment;

-

• recommendations on questions requiring further research to inform clinical practice;

-

• an assessment of any wider implications for the NHS;

-

• a concise summary of the reasoning behind NICE's recommendations and the evidence considered.

NICE also prepares guidance for users and carers, consulting with appropriate patient groups on the best format and means of dissemination. This guidance will explain the nature of the clinical recommendations, the implications for the standards that patients can expect and the broad nature of the evidence on which the recommendations are based.

The Department of Health has formally announced the first group of technologies for NICE to appraise, a number of which are relevant to the field of psychiatry (Boxes 2 and 3).

Box 2. Technologies for appraisal in autumn 1999

-

• Hip prosthesis

-

• Advances in hearing aids

-

• Routine wisdom teeth extraction

-

• Liquid-based cytology

-

• Coronary stent developments

-

• Taxanes for ovarian and breast cancer

-

• Inhaler devices for childhood asthma

-

• Proton pump inhibitors for treatment of dyspepsia

-

• Interferon beta and glutarimer for multiple sclerosis

-

• Zanamivir and oseltamivir for influenza

Box 3. Technologies to be appraised early in 2000

-

• Laparoscopic surgery

-

• Wound care

-

• Implantable cardioverter defibrillators

-

• Autologous cartilage transplantation

-

• Riluzole for motor neuron disease

-

• Ritalin for hyperactivity

-

• Ribavirin and alpha interferon for hepatitis C

-

• Cox II inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis

-

• Orlistat and sibutramine for obesity

-

• Glitazones for type II diabetes

-

• Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors

-

• New pharmaceuticals for Alzheimer's disease

Clinical guidelines

Academic centres, professional organisations and enthusiastic individuals in the UK have made major contributions to the production of clinical guidelines. The UK has also made a very significant contribution to the international development of a shared understanding of the methodology underpinning the construction of high-quality clinical guidelines. Despite this academic and professional leadership, however, there has (until now) been no national authority for clinical guidelines in England and Wales. Moreover, although clinical guideline developers have been moving in the same direction, there remains a degree of variation in approaches to clinical guideline development.

The Department of Health and the National Assembly for Wales have charged NICE with developing and disseminating Òrobust and authoritative” clinical guidelines. In constructing its clinical guidelines, NICE is expected to take into account both clinical and cost-effectiveness. Where relevant, NICE seeks to produce parallel clinical guidelines for patients and their carers.

In the past, many clinical guidelines have been produced by professional associations to aid the professional practice of their members. However, the primary duty of a professional association is to its members. NICE is a special health authority of the NHS, and its clinical guideline programmes will need to pay attention to the legitimate interests of all those with an involvement in the quality of NHS services.

Key principles

Ten key principles will underpin the way in which NICE handles clinical guideline development on behalf of the NHS (Box 4). While there will be many differences between the different kinds of guidelines it produces, the key principles should be relevant to its approach to all clinical guideline developments.

Box 4. Ten key principles for NHS clinical guidelines

-

• The objective of clinical guidelines is to improve the quality of clinical care by making available to health professionals and patients well-founded advice on best practice

-

• Quality care is based on clinical effectiveness – the extent to which the health status of patients can be expected to be enhanced by clinical interventions

-

• Quality of care in the NHS necessarily includes giving due attention to the cost-effectiveness of health care interventions

-

• NHS clinical guidelines are advisory, not statutory

-

• NHS clinical guidelines are based on the best possible research evidence, expert opinion and professional consensus

-

• NHS clinical guidelines are developed using methods that command the respect of patients, the NHS and NHS stakeholders

-

• While clinical guidelines are focused on the clinical care provided by clinicians, patients are to be treated as full and equal partners along with the relevant professional groups involved in a clinical guideline development

-

• All those who might be affected by a clinical guideline deserve consideration during its (usually including clinicians, patients and their carers, service managers, the wider public, Government and the health care industries)

-

• NHS clinical guidelines should be both ambitious and realistic

-

• NHS clinical guidelines should set out the clinical care that might reasonably be expected throughout the NHS

Status of NICE clinical guidelines

The NHS clinical guidelines will provide advice to assist the decision-making of practitioners and patients. They will be decision aids that will not have mandatory force. However, the way in which they have been developed and presented should be such that few recipients would ever have cause to dispute the basis of the recommendations.

Quality in clinical guideline development

It is generally accepted that all good clinical guidelines have a number of features in common. These quality criteria were developed initially in the early 1990s in the USA, and have been further developed so that they can be applied routinely to any clinical guidelines. The attributes include validity, reliability, reproducibility, clinical applicability, clinical flexibility, clarity, multi-disciplinary process, scheduled review and documentation. This approach seeks to ensure that producers of clinical guidelines have minimised the biases inherent in the production process. Clinical guideline recommendations should be based on the best available evidence; where this is not accessible, they should demonstrate how expert judgement has been incorporated into the recommendations.

These principles underpin several published instruments and current work on clinical guidelines (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 1995; Health Care Evaluation Unit, 1998). They will also be applied by NICE when it commissions or develops its own clinical guidelines.

NICE's clinical guidelines will be seen as having a particularly authoritative position within the NHS. This has not necessarily been the case for previous clinical guideline developers. For this reason, the NHS and NICE will expect that clinical guideline developments will give increased attention to patients' interests and issues of cost-effectiveness and implementation.

Responsibility for selecting the clinical guideline topics referred to NICE rests with the Secretary of State for Health and the National Assembly for Wales. The first programme (Box 5) was derived from a careful scrutiny of areas that are likely to have a significant impact on the NHS. The programme will be overseen by a Guidelines Committee chaired by Professor Martin Eccles.

Box 5. Topics for clinical guidelines to be completed or commissioned

-

• Management of schizophrenia

-

• Prevention and treatment of pressure sores

-

• National cancer group programme

-

• Peptic ulcer and dyspepsia

-

• Depressive illness in the community

-

• Acute myocardial infarction

-

• Management of completed myocardial infarction in primary care

-

• Hypertension

-

• Multiple sclerosis

-

• Routine pre-operative investigations

-

• Non-insulin-dependent diabetes

Referral advice

One of the key reasons for the establishment of NICE was to reduce variation in the quality of care provided by the NHS. This variation can be manifested in many ways, and one important area is access from primary care to specialist centres. There is now considerable research describing the variability in general practitioner out-patient referral rates, but less understanding of the underlying reasons for this. Key to an effective and efficient health service is the appropriate and timely referral of those patients who will benefit from specialist intervention. In October 1999 the Department of Health and the National Assembly for Wales invited NICE to produce an initial set of out-patient referral advice guidelines (Box 6). These would offer advice to general practitioners on when to refer patients to specialists. The guidelines were to be available by April 2000. In fact, a pilot version was published on the website in May 2000, and they will be launched nationally at the end of 2000.

Box 6. Topics proposed for referral guidelines

-

• Atopic eczema in children

-

• Acne

-

• Psoriasis

-

• Acute lower-back pain

-

• Osteoarthritis of the hip

-

• Osteoarthritis of the knee

-

• Glue ear in children

-

• Recurrent acute sore throat in children

-

• Dyspepsia

-

• Varicose veins

-

• Urinary tract (outflow) symptoms

-

• Menorrhagia

This was a challenging timetable in a field with little research evidence on how it should be approached. Drawing on the experience of developing local protocols in the South Thames Region and Newcastle-upon-Tyne, a methodology was designed that adhered to NICE's generic principals of rigour, transparency and inclusion of all stakeholders.

A steering group was convened to oversee the project. Advisory groups were created to modify and adapt advice created by the NICE project team. Each group included general practitioners, specialists and patient advocates. The documents are designed to provide advice on when patients should be referred: they are not clinical guidelines on how to manage patients. When NICE's guidelines programme is established, all of its clinical guidelines will include referral advice. It is anticipated that the next series will include subjects relevant to the field of psychiatry.

Clinical audit

The National Institute for Clinical Excellence also has responsibility for supporting clinical audit. In addition to producing audit advice to accompany all its guidance, it has been allocated the budgets for the Royal Colleges' audit units, the national sentinel audits and the confidential enquiries. It is in the process of reviewing these to assess how they can best support the drive towards clinical and cost-effectiveness in the NHS.

Conclusions

What is NICE's contribution to the debate on NHS quality, and particularly its relevance to psychiatry? NICE is unashamedly about defining best practice, based on the best research evidence that can be found, together with a systematic approach to professional and public opinion. We hope this will lead to informed expectations, both of what the medical profession hopes to achieve and also what the public and users of the service can expect. Much of the guidance that the Institute will issue in the coming year will be of specific relevance to the field of psychiatry and therefore should assist in the implementation of the Mental Health National Service Framework.

Fig. 1 Setting, delivering and monitoring standards

Fig. 2 The appraisal process

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.