Maternal depression

Maternal depression is common, and can be experienced during pregnancy (antenatal depression) and after the child is born (postpartum depression). Depression negatively affects the way a person with depression thinks, feels and acts. The symptoms of depression are detected by the use of questionnaires (for example the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)), or diagnosed using a clinical interview such as the DSM or the ICD.1 Among mothers in high-income countries, antenatal depression affects 7–12%Reference Deave, Heron, Evans and Emond2 and postpartum depression affects 13–18% within the first year after childbirth.Reference Gavin, Gaynes, Lohr, Meltzer-Brody, Gartlehner and Swinson3,Reference O'Hara and Swain4 Depression causes personal suffering and weakens a person's ability to function in general. A woman with depression in the perinatal period is also faced by the challenges of the antenatal transition into motherhood, and after giving birth, the responsibility of taking care of her infant. Supportive parenting is known to be one of the strongest predictors of good outcomes for children.Reference Barlow and Coren5 Longitudinal studies from many countries show that positive, consistent and supportive parenting predicts low levels of child problem behaviour and child abuse, and also predicts enhanced cognitive development.Reference Hoeve, Dubas, Eichelsheim, Van Der Laan, Smeenk and Gerris6–Reference Allely, Purves, McConnachie, Marwick, Johnson and Doolin12 Conversely, harsh inconsistent parenting predicts a broad range of poor child outcomes.Reference Hoeve, Dubas, Eichelsheim, Van Der Laan, Smeenk and Gerris6,Reference Rutter13–Reference Scott, Lewsey, Thompson and Wilson16

Several studies have shown that increased levels of depressive symptoms in the parent are associated with less sensitive and harsher parenting behaviours.Reference Stack, Serbin, Girouard, Enns, Bentley and Ledingham17–Reference Gershoff, Aber and Lennon19 Mothers with depression tend to demonstrate a flatter affect and be less sensitive, less responsive and less affectively attuned to their infants' needs, thus violating the infants' basic needs for positive interaction.Reference Field20,Reference Reck, Hunt, Fuchs, Weiss, Noon and Moehler21 Maternal depression is a major risk for the infant. The first months of life are a highly sensitive period during which the infant is dependent on maternal care, and during which early brain and socioemotional development take place.Reference Feldman22 The negative impact of maternal depression on early child development is well documented and includes a broad range of child outcomes and increased susceptibility to psychopathology.Reference Field20,Reference Murray, Cooper and Fearon23–Reference Netsi, Pearson, Murray, Cooper, Craske and Stein29 Maternal depression is frequently considered a unitary construct, but depressive symptoms do not follow a uniform course and there is a great diversity among mothers with depression.Reference Fredriksen, von Soest, Smith and Moe30–Reference Smith-Nielsen, Tharner, Steele, Cordes, Mehlhase and Vaever32 In accordance with cumulative risk theories (the more stressors and risk factors a child is exposed to, the bigger their risk of developing mental illness), the most adverse child outcomes are linked to high-risk populations where the depressive symptoms occur in combination with risk factors such as poverty and comorbid psychopathology.Reference Smith-Nielsen, Tharner, Steele, Cordes, Mehlhase and Vaever32–Reference Belsky, Fearon, Cassidy and Shaver35

The relationships between parental depression and such factors as parental competences, parental sensitivity, parent–child relationship and child development are complex and still not fully explained. Parental depression may influence the child through three potential mechanisms: (a) a direct causal relationship through genetic inheritance of risk genes from parent to child, (b) through shared environmental factors during pregnancy that have an impact on both maternal depression and child development (for example poverty), and (c) through the influence of parental depression on parent behaviour, on the quality of the parent–child relationship and on the overall functioning of the family, which lead to poorer outcomes for the child.Reference Galbally and Lewis36

Existing research

Based on previous studies, we know that interventions that focus solely on the mother (such as medication or psychotherapy targeting the depressive symptoms) are insufficient to buffer against the potentially negative impact of psychopathology on the child's cognitive and psychosocial development, as well as attachment.Reference Boyd and Gillham37–Reference Poobalan, Aucott, Ross, Smith, Helms and Williams40 Previous reviews of the effects of interventions for parents with depressive symptoms that include outcomes on the parent–child relationship or child development outcomes have focused on a broad range of psychological interventions aimed at treating depression in women with antenatal depression or postpartum depression.Reference Nylen, Moran, Franklin and O'Hara39–Reference Letourneau, Dennis, Cosic and Linder44 All reviews explicitly state that their results are either tentative or that evidence is insufficient to draw firm conclusions from. Still, five out of six reviews conclude that the interventions show promising results. Three of the reviews conducted meta-analyses.Reference Kersten-Alvarez, Hosman, Riksen-Walraven, Van Doesum and Hoefnagels41,Reference Cuijpers, Weitz, Karyotaki, Garber and Andersson42,Reference Letourneau, Dennis, Cosic and Linder44

The first review, published in 2011, focused on interventions aimed at enhancing maternal sensitivity, but did not address child developmental outcomes.Reference Kersten-Alvarez, Hosman, Riksen-Walraven, Van Doesum and Hoefnagels41 The second review, published in 2015, focused on psychological treatment of depression in mothers.Reference Cuijpers, Weitz, Karyotaki, Garber and Andersson42 The study included meta-analyses of both the mother–child relationship and child mental health outcomes, but mixed observational and parent-reported measures in the analyses. The third review, published in 2017 by Letourneau and colleagues, focused on interventions aimed at treating perinatal depression.Reference Letourneau, Dennis, Cosic and Linder44 Their meta-analysis focused only on the effect of two types of interventions: interpersonal psychotherapy and cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT). Each meta-analysis included two studies only, which is not ideal.Reference Valentine, Pigott and Rothstein45

We found no previous reviews focusing specifically on the effect of interventions aimed at improving parenting including both the parent–child relationship and child development outcomes. The objective of this review is therefore to systematically review the effects of parenting interventions on the parent–child relationship and child development outcomes when offered to pregnant women or mothers with depressive symptoms who have infants aged 0–12 months. We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of interventions that aimed at improving parenting in a broad sense (such as Circle of SecurityReference Woodhouse, Powell, Cooper, Hoffman, Cassidy, Steele and Steele46 or Minding the BabyReference Slade, Holland, Ordway, Carlson, Jeon and Close47) and that reported on the parent–child relationship (for example attachment or parent–child relationship) or child development (for example socioemotional or cognitive development) outcomes at post-intervention or follow-up.

Method

This review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). We did not register a protocol.

Search strategy

The latest database search was performed in September 2018. Ten international bibliographic databases were searched: Campbell Library, Cochrane Library, CRD (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination), ERIC, PsycINFO, PubMed, Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Care Online, Social Science Citation Index and SocIndex. Operational definitions were determined for each database separately. The search strategy was developed in collaboration between an information specialist and a member of the review team (M.P.), and comprised three separate reviews on parenting interventions.Reference Pontoppidan, Klest, Patras and Rayce48,Reference Rayce, Rasmussen, Klest, Patras and Pontoppidan49 The main search comprised combinations of the following terms: infant*, neonat*, parent*, mother*, father*, child*, relation*, attach*, behavi*, psychotherap*, therap*, intervention*, train*, interaction, parenting, learning and education (see supplementary File 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.89). To identify studies on women with depression or depressive symptoms in the perinatal period, the search also included the term depress*. The searches included Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), Boolean operators and filters. Publication year was not a restriction. Furthermore, we searched for grey literature, hand searched four journals and snowballed for relevant references.

Eligibility criteria and study selection

All publications were screened based on title and abstract. Publications that could not be excluded were screened based on the full-text version. Each publication was screened independently by two research assistants under close supervision by S.B.R. and M.P. Uncertainties regarding inclusion were discussed with S.B.R. or/and M.P. Screening was performed in Eppi-Reviewer 4. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

We developed a data extraction tool for the descriptive coding and extracted information on (a) study design, (b) depression inclusion criteria, (c) sample characteristics, (d) intervention characteristics, (e) setting, (f) outcome measures, and (g) child age at post-intervention and at follow-up. The information was extracted by a research assistant and checked by S.B.R. Primary outcomes were (a) parent–child relationship and (b) child socioemotional development. Secondary outcomes comprised other child development markers, for example cognitive and language development. The numeric coding was conducted independently by two reviewers (S.B.R. and I.S.R.). Disagreements were resolved by discussion, and, if necessary, a third reviewer was consulted.

We assessed risk of bias separately for each relevant outcome for all studies based on a risk of bias model developed by Professor Barnaby Reeves and the Cochrane Non-randomised Studies Method Group (Reeves, personal communication, 2019 from Reeves, Deeks, Higgins and Wells, unpublished data, 2011). This extended model follows the same steps as the risk of bias model presented in the Cochrane Handbook, Chapter 8.Reference Green, Higgins, Alderson, Clarke, Mulrow and Oxman50 The risk of bias assessment was conducted by I.S.R. and checked by S.B.R. Any doubts were resolved by consulting a third reviewer.

Data analysis

We calculated effect sizes for all relevant outcomes where sufficient data was provided. Effect sizes are reported using standardised mean differences (Cohen's d) with 95% CI for continuous outcomes. Data include post-intervention and follow-up means (or mean differences), raw s.d.s and sample size. For dichotomous outcomes, we used risk ratios (RR) with 95% CI. If a paper provided insufficient information regarding numeric outcome, the corresponding author was contacted. When available, we used data from adjusted analyses to calculate effect sizes. When adjusted mean differences were calculated, we used the unadjusted s.d.s to be able to compare effect sizes calculated from unadjusted and adjusted means. To calculate effect sizes, we used the Practical Meta-Analysis Effect Size Calculator developed by David B. Wilson, George Mason University and provided by the Campbell Collaboration.Reference Wilson51

Meta-analysis was conducted when outcome and time of assessment were comparable. When a single study provided more than one relevant measure, or only subscales of an overall scale for the meta-analysis, the effect sizes of the respective measures were pooled into a joint measure before being entered in the meta-analysis. One study consisted of three separate intervention arms and a shared control group.Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52 Since three effect sizes based on the same control group would not be independent, we calculated an effect size based on a mean of the three intervention groups' means and the mean of the control group.

Random-effects inverse-variance-weighted mean effect sizes were applied and 95% CIs were reported. Thus, studies with larger sample sizes were given more weight, all else being equal. Based on the relatively small number of studies and on an assumption of between-study heterogeneity, we used a random-effects model using the profile-likelihood estimator as suggested in Cornell.Reference Cornell53 Variation in standardised mean difference that was attributable to heterogeneity was assessed with the I 2. The estimated variance of the true effect sizes was assessed by the Tau2 statistic. The small number of studies in the meta-analysis did not allow for subgroup analyses.

Assessment times were divided into post-intervention (at intervention ending), short-term (less than 12 months after intervention ending) and long-term (12 months or more) follow-up.

Results

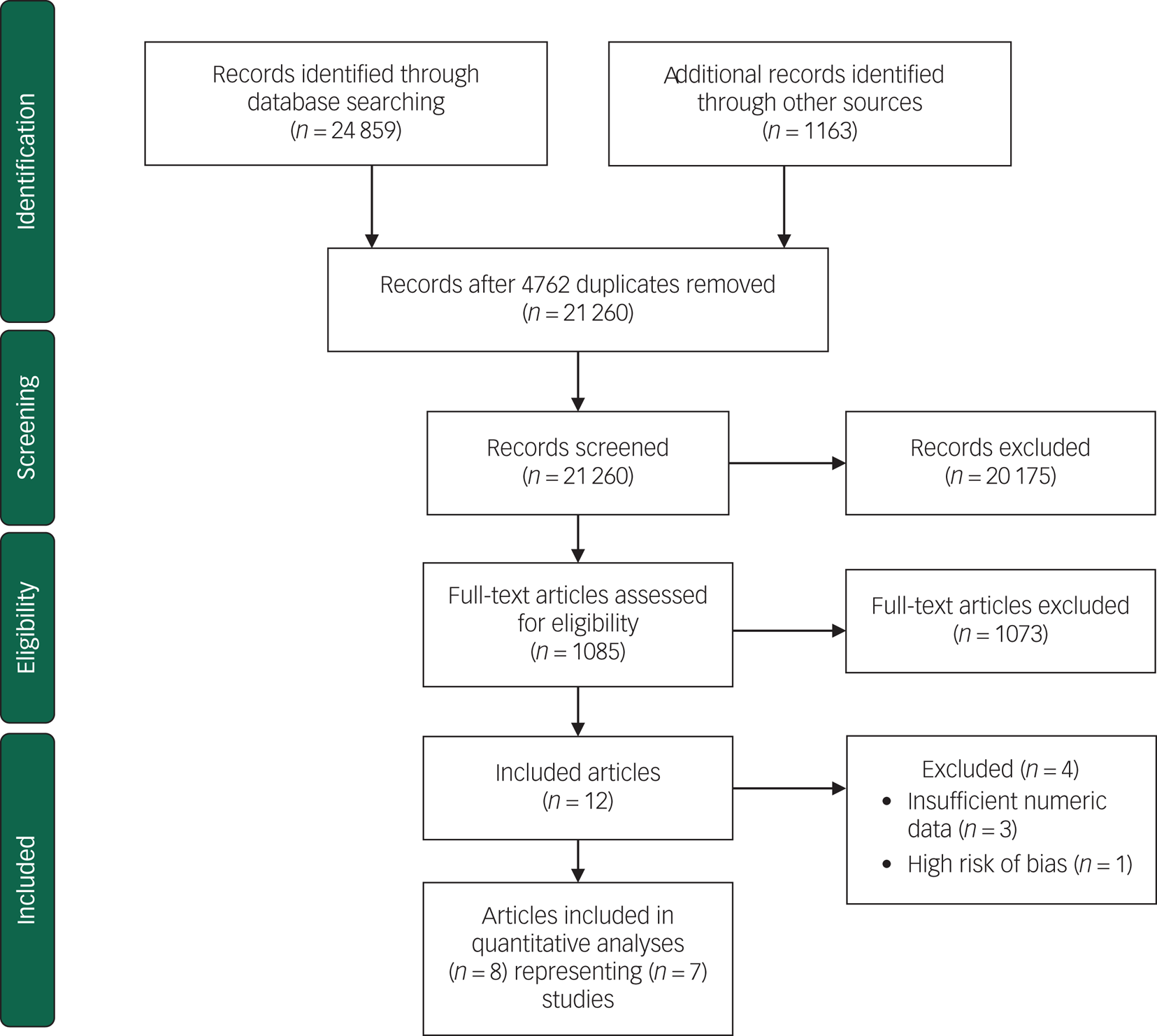

The search identified 21 260 articles after removal of duplicates. After first- and second-level screening 12 articles remained. A further three articles were excluded because of insufficient numerical data and one was excluded because of high risk of bias. See Fig. 1 for a flow chart of the process. Seven randomised controlled trials (eight published papers) met all inclusion criteria and were included in this review.Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52,Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman55–Reference Stein, Netsi, Lawrence, Granger, Kempton and Craske61

Fig. 1 Flow diagram for study selection process.Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman54

All studies were randomised at the individual level. Three studies were American,Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman55–Reference Horowitz, Murphy, Gregory, Wojcik, Pulcini and Solon57 two were British,Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52,Reference Stein, Netsi, Lawrence, Granger, Kempton and Craske61 one was CanadianReference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson58 and one study presented in two papers was Dutch.Reference Van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels59,Reference Kersten-Alvarez, Hosman, Riksen-Walraven, Van Doesum and Hoefnagels60 Three studies were excluded because of insufficient numeric dataReference Tsivos, Calam, Sanders and Wittkowski62–Reference Puckering, McIntosh, Hickey and Longford64 and one study was excluded because of unacceptably high risk of bias.Reference Ericksen, Loughlin, Holt, Rose, Hartley and Buultjens65

Participant characteristics

Table 2 presents participant characteristics. No studies started during pregnancy. All women were included based on specific inclusion criteria for level of depressive symptoms. Four studies used the EPDS,Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman55–Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson58 one study used the EPDS or a DSM-II-R major depressive disorder diagnosis,Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52 one study used a diagnosis of major depressive disorder,Reference Stein, Netsi, Lawrence, Granger, Kempton and Craske61 and one study used the Beck Depression Inventory or DSM-IV major depressive episode or dysthymia diagnosisReference Van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels59,Reference Kersten-Alvarez, Hosman, Riksen-Walraven, Van Doesum and Hoefnagels60 as inclusion criteria. The mean age of the mothers at inclusion ranged from 27.7 to 32 years and mean age of the infant between 1 and 7 months. Two studies included primiparous mothers only,Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52,Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman55 whereas the other five included both primiparous and multiparous mothers.Reference Horowitz, Bell, Trybulski, Munro, Moser and Hartz56,Reference Horowitz, Murphy, Gregory, Wojcik, Pulcini and Solon57,Reference Van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels59–Reference Stein, Netsi, Lawrence, Granger, Kempton and Craske61,Reference Gilmer, Buchan, Letourneau, Bennett, Shanker and Fenwick66 In most studies, the majority of participants were White, married/living with partner, and with a medium or long education. All studies were relatively small, ranging from 42 to 190 participants.

Table 2 Participant characteristics

EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory.

Intervention characteristics

Table 3 presents intervention characteristics, assessment times and outcomes. All included studies offered individual home visits initiated postpartum. No studies offered a group-based intervention. Most interventions focused on supporting the parent–child relationship through for example video feedback, coaching or therapy. Four studies offered alternative treatment such as progressive muscle relaxation, home visits or phone calls to the control group.Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman55,Reference Horowitz, Murphy, Gregory, Wojcik, Pulcini and Solon57,Reference Van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels59,Reference Stein, Netsi, Lawrence, Granger, Kempton and Craske61 One study also provided CBT for both the intervention and control group.Reference Stein, Netsi, Lawrence, Granger, Kempton and Craske61 Control condition was usual care in two studiesReference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52,Reference Horowitz, Bell, Trybulski, Munro, Moser and Hartz56 and waiting list in one study where participants received usual care while waiting.Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson58 Besides one intervention lasting 7.5 months,Reference Horowitz, Bell, Trybulski, Munro, Moser and Hartz56 all interventions were relatively short (3–15 weeks) and the intensity ranged between weekly visits to one visit a month.

Table 3 Intervention characteristics, assessment times and outcomes

Goodman and colleagues (2015) examined the effects of Perinatal Dyadic Psychotherapy among 42 mothers recruited from postpartum units of three hospitals located in the USA.Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman55 The study was a pilot study to examine a novel dual-focused mother–infant intervention aimed at promoting maternal mental health and improving the relationship between mother and infant. The intervention was derived from the mutual regulation model by Tronick,Reference Tronick67 and integrates clinical strategies of supportive psychotherapy, parent–infant psychotherapy, the touchpoints model of child developmentReference Brazelton and Sparrow68 and the newborn behavioral observation.Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman55,Reference Nugent, Keefer, Minear, Johnson and Blanchard69

Horowitz and colleagues (2001) examined the effects of an interactive coaching intervention among 117 mothers from greater Boston in the USA.Reference Horowitz, Bell, Trybulski, Munro, Moser and Hartz56 The aim of the intervention was to improve responsiveness between infant and mother. The intervention is based on Beck's cognitive model of depression,Reference Beck70 Sameroff's transactional model of child developmentReference Sameroff and Zeanah71 and Rutter's model of developmental risk and resilience.Reference Horowitz, Bell, Trybulski, Munro, Moser and Hartz56

Horowitz and colleagues (2013) examined the effects of the behavioural coaching intervention communicating and relating effectively on 134 mother–infant dyads in the USA.Reference Horowitz, Murphy, Gregory, Wojcik, Pulcini and Solon57 The intervention aimed to improve the mother–infant relationship. The intervention is based on cognitive–behavioural family therapy theory.Reference Horowitz, Murphy, Gregory, Wojcik, Pulcini and Solon57

Letourneau and colleagues (2011) examined the effects of home-based peer support among 60 mothers in Canada.Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson58 The home-based peer support included mother–infant interaction teaching as an important element and the intervention aimed to improve interactions between mothers and their infants. The intervention is not based on any specific theory, but the authors refer to concepts from studies on mothers with postpartum depression and peer support.Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson58

Murray and colleagues (2003) examined the effects of three different, but related, interventions: (a) CBT, (b) psychodynamic therapy and (c) non-directive counselling in one trial in the UK.Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52 In total, 190 first-time mothers were included and almost equally distributed among the three intervention groups and the single control group. The interventions all aimed to improve the mother–child relationship. The CBT intervention was a modified form of interaction guidance treatment. In the psychodynamic therapy intervention, the mother's representations were used to explore her own attachment history. The non-directive counselling intervention provided the mothers with an opportunity to talk about their feelings about current concerns.Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52

Stein and colleagues (2018) examined the effects of video-feedback therapy among 144 mothers in the UK. The aim of the intervention was to improve parenting behaviours (attention to infant cues, emotional scaffolding and sensitivity). Both intervention and control families also received CBT with a focus on behavioural activation. The control group received progressive muscle relaxation that did not target parent practices or parent–child interaction.Reference Stein, Netsi, Lawrence, Granger, Kempton and Craske61

Van Doesum and colleagues (2008) examined the effects of a mother–baby intervention among 71 mothers in the Netherlands.Reference Van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels59,Reference Kersten-Alvarez, Hosman, Riksen-Walraven, Van Doesum and Hoefnagels60 The intervention aimed to improve the mother–infant interaction, particularly maternal sensitivity. The intervention was based on video feedback, modelling, cognitive restructuring, practical pedagogical support and baby massage.Reference Van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels59,Reference Kersten-Alvarez, Hosman, Riksen-Walraven, Van Doesum and Hoefnagels60

Outcome characteristics

All seven studies examined parent–child relationship outcomes. Measures applied to assess parent–child relationship (for example attachment or parent–child relationship) included the Emotional Availability Scales (EAS),Reference Van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels59 Coding Interactive Behavior (CIB),Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman55 the Nursing Child Assessment Teaching ScaleReference Horowitz, Murphy, Gregory, Wojcik, Pulcini and Solon57 and the Dyadic Mutuality Code.Reference Horowitz, Bell, Trybulski, Munro, Moser and Hartz56 Four studies assessed child development outcomes (such as socioemotional or cognitive development) with measures such as the Infant-Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (ITSEA),Reference Van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels59 the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)Reference Kersten-Alvarez, Hosman, Riksen-Walraven, Van Doesum and Hoefnagels60,Reference Stein, Netsi, Lawrence, Granger, Kempton and Craske61 and Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID).Reference Stein, Netsi, Lawrence, Granger, Kempton and Craske61 Outcomes were assessed by independent assessors (for example EAS, CIB, and BSID), by parents (for example ITSEA and CBCL), and/or teachers (for example CBCL). All seven studies included a post-intervention assessment, but only four studies included a follow-up assessment.Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52,Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman55,Reference Van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels59–Reference Stein, Netsi, Lawrence, Granger, Kempton and Craske61 As the development of maternal depressive symptoms is not the focus of this review, we did not include maternal depression in our analyses, although it was reported in all studies.

Risk of bias

Risk of bias assessments for each study's outcomes are displayed in online supplementary Table 1 divided into parent–child relationship and child development outcomes. Six out of seven studies provided insufficient information for one or more risk of bias domain, thus hindering a clear risk of bias judgement. Only two studiesReference Kersten-Alvarez, Hosman, Riksen-Walraven, Van Doesum and Hoefnagels60,Reference Stein, Netsi, Lawrence, Granger, Kempton and Craske61 provided an accessible a priori protocol, which made it particularly difficult to assess risk of bias caused by selective reporting. In general, risk of bias ranged between low and medium. Five studies had outcomes where one or two domains were classified as medium risk of bias.Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52,Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman55,Reference Horowitz, Murphy, Gregory, Wojcik, Pulcini and Solon57,Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson58,Reference Stein, Netsi, Lawrence, Granger, Kempton and Craske61 Only one study had outcomes with a high risk of bias in one domain: ‘incomplete outcome data addressed’.Reference Kersten-Alvarez, Hosman, Riksen-Walraven, Van Doesum and Hoefnagels60 One study was excluded from the review because of an unacceptably high risk of bias caused by lack of assessor masking and high risk of bias in relation to ‘incomplete outcome data addressed’.Reference Ericksen, Loughlin, Holt, Rose, Hartley and Buultjens65

The outcomes included in the meta-analysis on the parent–child relationship were characterised by low-to-medium and unclear risk of bias domain. In three of these studies,Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52,Reference Horowitz, Bell, Trybulski, Munro, Moser and Hartz56,Reference Van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels59 the risk of bias domains of the outcomes were assessed as relatively low (1–2) or unclear risk of bias. The outcomes of the remaining three studiesReference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman55,Reference Horowitz, Murphy, Gregory, Wojcik, Pulcini and Solon57,Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson58 were characterized by low-to-medium and unclear risk of bias.

Parent–child relationship

Seven studies reported on parent–child relationship outcomes.Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52,Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman55–Reference Van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels59,Reference Stein, Netsi, Lawrence, Granger, Kempton and Craske61 supplementary Table 2 presents the study outcomes for the individual studies. Owing to the lack of follow-up assessments, only meta-analysis of the parent–child relationship post-intervention was conducted.

Post-intervention parent–child relationship

The meta-analysis of the effect of the parenting intervention on the parent–child relationship at post-intervention included 573 participants from six studies and is presented in Fig. 2.Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52,Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman55–Reference Van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels59 No significant effect of the parenting interventions on the parent–child relationship was found (d = 0.028, 95% CI −0.30 to 0.31) (I 2 = 49.02). One studyReference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson58 that provided a peer-support intervention instead of using professional providers was removed for sensitivity analysis. This did not alter the result substantially. Likewise, three studies offering alternative treatment for the control groupReference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman55,Reference Horowitz, Murphy, Gregory, Wojcik, Pulcini and Solon57,Reference Van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels59 were removed for sensitivity analysis. The result of the meta-analysis of the three remaining studies that provided treatment as usualReference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52,Reference Horowitz, Bell, Trybulski, Munro, Moser and Hartz56,Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson58 was not altered substantially. All six studies were therefore kept in the analysis.

Fig. 2 Meta-analysis of studies reporting parent–child relationship at post-intervention.

One out of the two parent–child relationship outcomes in the study by Murray et al Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52 was based on a parent-reported questionnaire. As all other outcomes included in the meta-analysis were observational measures, this outcome was not included in the analysis. When examining relationship problems, Murray et al (2003) found significant positive effects of counselling, psychodynamic therapy and CBT compared with usual care (counselling: RR = 0.63, 95% CI 0.32–0.97); psychodynamic: RR = 0.57, 95% CI 0.28–0.92); cognitive–behavioural: RR = 0.46, 95% CI 0.20–0.81).Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52

Parent–child relationship at short-term follow-up

Two studies reported on the parent–child relationship at short-term follow-up.Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman55,Reference Van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels59 Van Doesum and colleaguesReference Van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels59 found significant effects of the mother–infant intervention on maternal sensitivity (d = 0.82, 95% CI 0.34–1.31), maternal structuring (d = 0.57, 95% CI 0.09–1.04), child responsiveness (d = 0.69, 95% CI 0.21–1.16) and child involvement (d = 0.75, 95% CI 0.27–1.23) at short-term follow-up when the children were around 18 months old. No significant effects were found on child attachment security, maternal non-intrusiveness or maternal non-hostility.Reference Van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels59 Goodman and colleagues likewise measured maternal sensitivity and infant involvement but found no significant effects on maternal sensitivity, infant involvement or dyadic reciprocity when the children were around 8 months old.Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman55

Parent–child relationship at long-term follow-up

Three studies reported on the parent–child relationship at long-term follow-up.Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52,Reference Kersten-Alvarez, Hosman, Riksen-Walraven, Van Doesum and Hoefnagels60,Reference Stein, Netsi, Lawrence, Granger, Kempton and Craske61 Meta-analysis was not conducted, as the study by Stein and colleagues used an active control group, whereas the control groups in the two remaining studies received either alternative treatment or treatment as usual. Kersten-Alvarez and colleagues found no effects on maternal interactive behaviour or attachment security when the children were 4 years old.Reference Kersten-Alvarez, Hosman, Riksen-Walraven, Van Doesum and Hoefnagels60 Murray and colleagues found that none of the three interventions provided had a significant effect on child attachment at long-term follow-up (child aged 18 months) when compared with the control group.Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52 Stein and colleagues found no significant effects on attachment security for children aged 2 years.Reference Stein, Netsi, Lawrence, Granger, Kempton and Craske61

Child development

Four studies reported on child development outcomes. Supplementary Table 3 presents the study outcomes for the individual studies. Owing to the lack of developmental outcomes and follow-up assessments, it was not possible to conduct meta-analysis of child development.

Post-intervention child development

Two studies examined child development post-intervention.Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52,Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson58 Letourneau and colleagues found no significant effect on child cognitive and socioemotional development.Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson58 Murray and colleagues found that none of the three interventions provided had a significant effect on infant behaviour problems post-intervention.Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52

Child development at short-term follow-up

One study, van Doesum and colleagues, examined child development at short-term follow-up.Reference Van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels59 They found a significant effect of home visits on child competence behaviour (d = 0.62, 95% CI 0.14–1.10), but no significant effects on externalising, internalising or dysregulated behaviour.Reference Kersten-Alvarez, Hosman, Riksen-Walraven, Van Doesum and Hoefnagels60

Child development at long-term follow-up

Three studies examined child development at long-term follow-up (range: 13–56 months).Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52,Reference Kersten-Alvarez, Hosman, Riksen-Walraven, Van Doesum and Hoefnagels60,Reference Stein, Netsi, Lawrence, Granger, Kempton and Craske61 Murray and colleaguesReference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52 found significant positive effects of the counselling intervention (d = 0.64, 95% CI 0.22–1.05) and the psychodynamic intervention (d = 0.49, 95% CI 0.07–0.91) on emotional and behavioural problems when the children were 18 months old, but no effects of the cognitive–behavioural intervention at 18 months old. When the children were 60 months old, a positive significant effect of the cognitive–behavioural intervention on mother-rated emotional and behavioural difficulties (d = 0.61, 95% CI 0.12–1.11) was found, but not on teacher-rated emotional and behavioural difficulties. No significant effects of the two other interventions were found. None of the three interventions showed significant effects on child cognitive development at any of the two follow-up assessments. Kersten-Alvares and colleagues found no significant effects of the intervention on child self-esteem, verbal intelligence, prosocial behaviour, school adjustment and behaviour problems at long-term follow-up.Reference Kersten-Alvarez, Hosman, Riksen-Walraven, Van Doesum and Hoefnagels60 Stein and colleagues found no significant effects on cognitive and language development, behaviour problems, attention focusing, attentional shifting, inhibitory control and child emotion regulation.Reference Stein, Netsi, Lawrence, Granger, Kempton and Craske61

Discussion

Main findings

We identified eight papers representing seven trials that examined the effects of parenting interventions offered to pregnant women or mothers with depressive symptoms. As a result of the variety of assessment measures and study designs, only meta-analysis on the parent–child relationship at post-intervention was performed. We found no significant effect of parenting interventions on the parent–child relationship. When we examine the individual study outcomes, there was no significant effect on most of the child development and parent–child relationship outcomes reported in the papers.

Only two studies found significant effects on a child development outcome, both positive.Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52,Reference Van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels59 Four studies found significant effects on a parent–child relationship outcome, three positive and one negative, ranging between a large negative effect on infant involvement and a large positive effect on child responsiveness.Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk52,Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman55,Reference Horowitz, Bell, Trybulski, Munro, Moser and Hartz56,Reference Van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels59 The general lack of effect of the interventions aimed at mothers with depressive symptoms is consistent with previous reviews that examine a number of different types of interventions for mothers.Reference Nylen, Moran, Franklin and O'Hara39–Reference Letourneau, Dennis, Cosic and Linder44 Consequently, there is a need to consider whether the interventions currently offered to mothers with depressive symptoms are appropriate, or if other strategies should be tried out.

Previous research shows that the most adverse child outcomes are found in high-risk populations where the depressive symptoms occur in combination with poverty and comorbid psychopathology.Reference Smith-Nielsen, Tharner, Steele, Cordes, Mehlhase and Vaever32–Reference Belsky, Fearon, Cassidy and Shaver35 Families with a relatively high socioeconomic status may therefore not be affected as severely by postpartum depression as families with low socioeconomic status. The socioeconomic status of the families included in the studies of this review is relatively high; most participants are of White ethnicity, and only a relatively small number of the participants have no education or limited education and/or a low income. This may contribute to the non-significant effect on the parent–child relationship found in the meta-analysis and the generally non-significant results of the individual studies.

Interpretation of our findings and avenues for further research

Most studies included in this review used a screening questionnaire such as the EPDS to measure the level of depressive symptoms. A questionnaire is easy to use, but is also less precise than a depression diagnosis based on a clinical interview. Although the participants included in this review had a relatively high score on a depression screening questionnaire, they do not necessarily fulfil criteria for a clinical depression. The interventions might be effective if they were examined with a group of mothers with clinical depression, as such mothers may profit more from the intervention. Future studies could therefore be aimed at specific high-risk populations such as socioeconomically deprived mothers or women with clinical depression to examine if interventions are effective within such populations. Although there is a high correlation between antenatal depression and postpartum depression,Reference Austin, Tully and Parker72 and the relationship with the child starts to form during pregnancy, none of the interventions of the included studies were initiated during pregnancy.Reference Slade73 Therefore, screening for depression in pregnancy and starting treatment before the baby is born could be a focus for future research.

Previous reviews have pointed out that existing studies on psychological interventions for pregnant women or mothers with depression are few and have small sample sizes.Reference Poobalan, Aucott, Ross, Smith, Helms and Williams40,Reference Kersten-Alvarez, Hosman, Riksen-Walraven, Van Doesum and Hoefnagels41,Reference Tsivos, Calam, Sanders and Wittkowski43 Sample sizes of the studies included in this review ranged from 42 to 190 participants, which may have limited the power to detect significant effects. Although four of the studies included in this review include 100–190 participants, the studies are generally still small in sample size and limited in number in this updated review. We did not find any systematic differences according to study size. Future studies should have a larger sample size to increase power. In order to examine mechanisms of change, careful considerations about the need for moderator or mediator analyses should be made a priori, as this increases the required sample size considerably.Reference Breitborde, Srihari, Pollard, Addington and Woods74,Reference Kraemer75 Examples of possible moderators are socioeconomic status and depression level, and a possible mediator could be reflective functioning or sensitivity, depending on the theory of change in the examined intervention.

Several factors may moderate the effect of parenting interventions. First, intervention characteristics such as theoretical background may moderate the effect of parenting interventions. The interventions included in this review were, however, relatively comparable with regard to delivery, theoretical background and intensity. Most were home visits conducted by trained therapists, with weekly to monthly visits for a relatively short period.

Second, group format is widely used in parenting interventions and achieves change through the dual process of emotional experience and reflection in an interpersonal context.Reference Bieling, McCabe and Antony76,Reference Griffiths and Barker-Collo77 Group sessions provide a support network, reduce isolation and stigma, provide an environment in which to practice interpersonal and communication skills, and shape coping strategies and learning from each other. This may be important for mothers with depression as they may feel alone with their problems. We did not, however, find any studies that employed a group format. A group intervention (circle of security – parenting) offered to mothers with depression is currently being evaluated in a RCT in Denmark.Reference Væver, Smith-Nielsen and Lange78 The group format enables several families to be treated at once, making it cheaper than individual interventions.

Finally, in recent years both practice and research have become much more aware of the important role fathers can play.Reference Guterman, Bellamy and Banman79 The father–child relationship might be especially important to both the mothers and the children in the context of maternal problems, such as depression, in which the father might buffer negative effects on children's socioemotional development. At the same time, non-optimal paternal behaviour and father–child relationships might act as an additional risk factor for problematic child development.Reference Goodman, Lusby, Thompson, Newport and Stowe31,Reference Mezulis, Hyde and Clark80,Reference Lamb81 It is therefore crucial to consider how fathers can be involved in the support offered to new families. None of the studies in this review, however, included fathers in the intervention.

Limitations

We chose to include only RCTs or quasi-RCTs in the review to ensure high methodological quality and to minimise the risk of confounding factors. We consider this a strength of the review, but it may have reduced the number of included studies, thereby making it more difficult to find comparable studies for meta-analyses. Likewise, the small number of included studies hindered subgroup analysis, which must be considered a limitation. Although some studies did report short- or long-term follow-up outcomes, it was not possible to conduct meta-analysis on any follow-up outcomes. Consequently, we cannot say anything about the effects over time.

Another limitation that stems from the reviewed studies is that although the two most recent studiesReference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman55,Reference Stein, Netsi, Lawrence, Granger, Kempton and Craske61 addressed implementation issues such as details about certification, supervision, fidelity and variation in the number of intervention sessions received, most studies only provide limited information about training. Therefore, when comparing across studies, we do not have a clear picture of how well the interventions were delivered and whether the results could have been affected by implementation difficulties. A final limitation is that only studies conducted in Western Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries were included in this review. Since cultural norms and values related to parenting vary considerably across countries,Reference Gardner, Montgomery and Knerr82 we chose to focus on the effectiveness of interventions offered to families in high-income countries in this review. However, the majority of the world's population lives in low- and middle-income countries. Therefore, it is important to conduct similar reviews focusing on studies from low- and middle-income countries.

Implications for practice

This review, based on seven studies, provides no evidence for the effect of parenting interventions for mothers with depressive symptoms on the parent–child relationship immediately after the intervention ended. As meta-analysis for child development or follow-up assessments could not be done, it remains unclear whether there are any effects on these outcomes. Despite the current accepted need to intervene within the first 1000 days of a vulnerable child's life, and the fact that parental depression can have serious developmental consequences for the child, we still lack high-quality studies to inform practice about how best to support vulnerable families. We also still lack systematic reviews that examine the effects of interventions for mothers with depression outside high-income countries.

Funding

S.B.R. and I.S.R. were supported by a grant from the Danish Ministry of Social Affairs and Interior. M.P. was supported by the Danish Ministry of Social Affairs and the Interior and grant number 7-12-0195 from Trygfonden.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank information specialists Anne-Marie Klint Jørgensen and Bjørn Christian Arleth Viinholt for running the database searches, Rikke Eline Wendt for being involved in the review process, Therese Lucia Friis, Line Møller Pedersen, Louise Scheel Hjorth Thomsen and Emilie Jacobsen for conducting the screening and senior researcher Trine Filges and senior researcher Jens Dietrichson for statistical advice.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.89.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.