Since the introduction of the concept of self-efficacy by Bandura (Reference Bandura1977), studies examining the relationship between self-efficacy and depression have found that those who score higher on measures of self-efficacy show substantially fewer symptoms of depression (Reference Cutrona and Trout manCutrona & Troutman, 1986; Reference McFarlane, Bellissimo and NormanMcFarlane et al, 1995). However, as elaborated by Bandura (Reference Bandura1997), self-efficacy is not a static characteristic. In theory, it can be altered by behaviour, by internal personal factors in the form of cognitive, affective and biological events, and by the external environment. This report provides a more complete evaluation of the relationship between self-efficacy and depression by examining the interrelationships between self-efficacy, stressful life events and symptoms of depression in a longitudinal study using a large community sample. In particular, we tested the following hypotheses: (a) symptoms of depression undermine self-efficacy; (b) stressful life events undermine self-efficacy; and (c) self-efficacy mediates the effect of stressful life events on symptoms of depression.

Context

One of the aims of the present study was to test the general validity of the notion that higher levels of self-efficacy result in fewer symptoms of depression. Prior studies lending support to this hypothesis have used context-specific measures of self-efficacy on narrowly defined populations perceived to be at risk for depression. Cutrona & Troutman (Reference Cutrona and Trout man1986) examined the relationship between parenting self-efficacy and post-partum depression (n=55). McFarlane et al (Reference McFarlane, Bellissimo and Norman1995) studied the influence of social self-efficacy on depression in a study of high-school students (n=682). In contrast to these studies, which explored the relationships between context-specific measures of self-efficacy and depression in narrowly defined study groups, we examined the relationship between a global measure of personal efficacy and depressive symptoms, using a large sample of respondents who participated in the Americans' Changing Lives (ACL) study.

Over the past three decades, there has been compelling evidence for an association between stressful life events and depression (Reference Brown and HarrisBrown & Harris, 1978; Reference Surtees, Miller and InghamSurtees et al, 1986; Reference Kendler, Kessler and WaltersKendler et al, 1995). However, although the majority of those who become depressed have recently suffered a stressful life event, studies indicates that at least part of the association between stressful life events and depression is non-causal (Reference PaykelPaykel, 1978; Reference Kendler, Karkowski and PrescottKendler et al, 1999). In particular, some studies have suggested that depression makes a person vulnerable to the subsequent experience of stressful life events (Reference HammenHammen, 1991). In the present study, we considered not only the possibility that depressive symptoms predict certain types of stressful life events, but also the possibility that part of the effect of stressful life events on depressive symptoms is mediated through the impact of stressful life events on self-efficacy.

The present study had three specific aims. First, we tested whether higher levels of global self-efficacy would result in fewer symptoms of depression. Second, we examined the effects of symptoms of depression and stressful life events on self-efficacy. Third, we estimated the degree to which the effect of stressful life events on symptoms of depression is mediated through self-efficacy.

METHOD

Sample

The ACL study was conducted by the Survey Research Center of the University of Michigan and we obtained the database through the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (Reference HouseHouse, 1994). The ACL is a multi-stage stratified area probability sample of people over the age of 25 living throughout the continental United States. African Americans and those 60 years of age and older were over-sampled. Designed as a longitudinal study of productivity and successful aging in the middle and later years of life, the ACL database includes measures relevant to the study of psychosocial influences on depression.

The ACL survey was conducted in waves, with a baseline survey in 1986 (Wave I) and a follow-up survey in 1989 (Wave II). At baseline, a sample of 3617 respondents was interviewed in their homes. At follow-up, 2867 of these respondents who were interviewed at baseline were reinterviewed; they represented 83% of the respondents at baseline who were still living at the time of the follow-up interview. Non-response did not vary significantly by age, race or other known characteristics of the respondents. Further information about the ACL study is provided elsewhere (Reference House, Kessler and HerzogHouse et al, 1990). We focused on those respondents in the ACL study interviewed both at baseline and at follow-up for whom data on variables of interest were available (n=2858, or 99.7% of the 2867 respondents interviewed at follow-up).

Because we hypothesised that the interrelationships between self-efficacy, life events and symptoms of depression would depend on whether there was a prior history of depression, the sample was divided into two groups: those not reporting (n=1610) and those reporting (n=1248) at least one period when they felt sad, ‘blue’ or depressed most of the time, or when they lost all interest and pleasure in things about which they usually care or enjoy. This period was required to have lasted at least one week and have occurred prior to baseline interview. Dividing up the sample in this way served to separate those without from those with a prior history of some form of acute depression, but not necessarily major depression.

Measures for modelling depressive symptoms

For each of the measures described below, ‘baseline’ refers to data acquired at the Wave I (1986) interview; ‘follow-up’ refers to data acquired at the Wave II (1989) interview.

Depressive symptoms

The severity of symptoms of depression was assessed at baseline and follow-up, using a standardised measure of an 11-item short form of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale developed by Kohout et al (Reference Kohout, Berkman and Evans1993). Kohout and his colleagues found this 11-item version to be reliable (Cronbach's α=0.81) and closely associated with the 20-item scale (r=0.95).

Self-efficacy

Personal beliefs about the ability to control one's environment and life circumstances generally — that is, one's global self-efficacy — were assessed at baseline and follow-up using a six-item standardised index (Cronbach's α=0.67) representing a combination of Rosenberg's (Reference Rosenberg1965) self-esteem scale and Pearlin & Schooler's (Reference Pearlin and Schooler1978) mastery scale. This measure of personal efficacy consisted of items that are similar to those introduced by Sherer and colleagues and consistent with the concept of self-efficacy as presented by Bandura (Reference BanduraBandura, 1977; Reference Sherer, Maddux and MecadanteSherer et al, 1982).

Stressful life events

Measures of stressful life events were based on events occurring within a period of 12 months prior to the follow-up interview. Interviewers documented events using a simple inventory, comprising: the death of a child, death of a spouse, death of a parent, death of a close friend or relative, divorce, move to a new residence, loss of job, a serious financial problem, physical attack, and life-threatening illness or injury. We focused on these types of events because they have been found to be predictive of the onset of depression (Reference Brown and HarrisBrown & Harris, 1978; Reference Kendler, Kessler and WaltersKendler et al, 1995), and because they represent events considered severe in nature as assessed by patients and community respondents alike (Reference Grant, Hervey and SweetwoodGrant et al, 1981).

Because we hypothesised that self-efficacy would tend to be undermined by stressful life events over which the individual might have reasonably had some control, we divided the life events that we considered into two categories; events judged to be almost certainly independent of the individual's behaviour, and events judged to be at least partly dependent on it. This division of life events into the categories ‘independent’ and ‘dependent’ is similar to that of Kendler et al (Reference Kendler, Karkowski and Prescott1999). In the present study, the independent events documented included death of a child (n=19), death of a spouse (n=30), death of a parent (n=96), and death of a close friend or relative (n=660). Dependent events included divorce (n=37), move to a new residence (n=314), loss of job (n=87), serious financial problem (n=216), physical attack (n=13), and life-threatening illness or injury (n=101). Summary measures were used to tally the number of stressful life events within each of these two categories for each respondent.

Control variables

A variety of factors have been associated with depression, including social and demographic factors (Reference Kessler, McGonagle and ZhaoKessler et al, 1994), chronic financial hardship (Reference Brown and MoranBrown & Moran, 1997), functional impairment (Reference Zeiss, Lewinsohn and RohdeZeiss et al, 1996) and chronic health conditions (Reference Black, Goodwin and MarkidesBlack et al, 1998). In order to ensure that results in the present study would not be confounded with these factors, measures for each were used as control variables in our models for predicting stressful life events, self-efficacy and symptoms of depression. More specifically, respondents' age, gender, race (Caucasian/non-Caucasian), socio-economic status, chronic financial stress, functional health status and number of chronic health conditions (each assessed at baseline) were employed as control variables. Socio-economic status was assessed using education and income level to classify respondents into two categories representing lower and upper socio-economic status. Chronic financial stress was determined by means of a standardised index based on the work of Pearlin & Schooler (Reference Pearlin and Schooler1978). This index assessed the respondent's degree of satisfaction with his/her present financial situation, degree of difficulty paying monthly bills, and ability to meet monthly financial obligations. Functional health status was assessed by the ability to do heavy housework without difficulty, and respondents were sorted into two categories, representing poor and good functional health. The number of chronic health conditions was assessed as the number of conditions afflicting the respondent, and included arthritis, lung disease, hypertension, heart attack, diabetes, cancer, foot problems, stroke, broken bones and urinary incontinence.

Analyses predicting symptoms of depression

We calculated t-statistics to test for differences between those without and those with prior depression (i.e. depressed for a period of at least one week at some time prior to the baseline interview) in terms of symptoms of depression, self-efficacy and number of life events. We calculated t-statistics and χ2-statistics to test for differences between these two groups with respect to each of the control variables.

A path model was used to evaluate the direct and indirect effects of the baseline level of symptoms of depression, self-efficacy at baseline, number of independent life events, number of dependent life events and self-efficacy at follow-up on symptoms of depression at follow-up. Path coefficients were estimated separately for those without and those with prior depression, for the purpose of exploring aetiological aspects of the relationship between self-efficacy, life events and severity of symptoms of depression. Symptoms of depression at baseline, self-efficacy at baseline, age, race, marital status, socio-economic status, chronic financial stress, functional health status and number of chronic health conditions were specified as exogenous variables. The number of independent life events, number of dependent life events at self-efficacy follow-up, and symptoms of depression at follow-up, were specified as endogenous variables. The sub-model for the number of independent life events consisted of paths from age and race. The sub-model for the number of dependent life events consisted of paths from self-efficacy at baseline, symptoms of depression at baseline, age, marital status, chronic financial stress, and number of chronic health conditions. The sub-model for self-efficacy at follow-up consisted of paths from self-efficacy at baseline, symptoms of depression at baseline, number of independent life events, number of dependent life events, age, marital status, socio-economic status, chronic financial stress, and number of chronic health conditions. The model for symptoms of depression at follow-up consisted of paths from symptoms of depression at baseline, number of independent life events, number of dependent life events, self-efficacy at follow-up, age, race, marital status, socio-economic status, chronic financial stress, functional health status and number of chronic health conditions.

The methods employed in the path analyses were consistent with those described in established texts (Reference BollenBollen, 1989; Reference LoehlinLoehlin, 1998). The overall fit of each path model was assessed by means of its model χ2, its goodness of fit index adjusted for degrees of freedom (AGFI), and its root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). We used t-statistics to assess the significance of individual path coefficients within each model.

RESULTS

As shown in Table 1, those with prior depression had significantly more severe symptoms of depression, lower levels of self-efficacy, and a greater number of dependent stressful life events, on average, than those without prior depression. Those with prior depression were significantly younger, more likely to be female, less likely to be married, and more likely to have poor functional health than those without prior depression. Those with prior depression also suffered significantly higher levels of chronic financial stress and a greater number of chronic health conditions.

Table 1 Comparison of study groups without and with prior depression

| Time of assessment | Prior depression1 | Comparative test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | No (n = 1610) | Yes (n = 1248) | ||

| Baseline | ||||

| Dichotomous measures | n (%) | n (%) | χ2 | d.f. |

| Gender (% female) | 976 (60.6%) | 848 (67.9%) | 16.35*** | 1 |

| Race (% caucasian) | 1047 (65.0%) | 855 (68.5%) | 3.82 | 1 |

| Marital status (% married) | 956 (59.4%) | 664 (53.2%) | 10.91*** | 1 |

| Socio-economic status (% upper) | 638 (39.6%) | 517 (41.4%) | 0.94 | 1 |

| Functional health status (% good) | 1309 (81.3%) | 941 (75.4%) | 14.63*** | 1 |

| Continuous measures | Mean (s.d.) | Mean (s.d.) | t | d.f. |

| Age | 54.5 (17.1) | 50.9 (16.9) | 5.70*** | 2856 |

| Chronic financial stress2 | -0.03 (1.01) | 0.19 (1.09) | -5.51*** | 2565 |

| No. of chronic health conditions3 | 1.27 (1.31) | 1.45 (1.45) | -3.20** | 2538 |

| Self-efficacy2 | 0.14 (0.95) | -0.20 (1.06) | 8.69*** | 2521 |

| Depressive symptoms3 | -0.16 (0.87) | 0.37 (1.15) | -13.74*** | 2258 |

| Follow-up | ||||

| Continuous measures | Mean (s.d.) | Mean (s.d.) | t | d.f. |

| No. of independent life events4 | 0.28 (0.47) | 0.29 (0.49) | -0.75 | 2856 |

| No. of dependent life events4 | 0.22 (0.48) | 0.33 (0.62) | -5.53*** | 2289 |

| Self-efficacy2 | 0.08 (0.98) | -0.18 (1.10) | 6.50*** | 2507 |

| Depressive symptoms3 | -0.13 (0.91) | 0.22 (1.12) | -8.86*** | 2364 |

Path coefficients for models predicting symptoms of depression at follow-up in samples without and with prior depression are presented in Table 2. For both of these groups, the existence of symptoms of depression at baseline and of self-efficacy at follow-up had strong, significant, direct effects on symptoms of depression at follow-up. In particular, greater self-efficacy at follow-up was associated with less severe symptoms of depression. The number of independent stressful life events had a significant, direct effect on symptoms of depression at follow-up for the group without prior depression, but not for the group with prior depression. The number of dependent stressful life events had a significant, direct effect on symptoms of depression at follow-up for both groups. Self-efficacy at baseline had a significant, indirect effect on symptoms of depression at follow-up for both the group without prior depression (βindirect=-0.114, s.e.=0.033, P < 0.001) and the group with prior depression (βindirect=-0.186, s.e.=0.036, P < 0.001).

Table 2 Path coefficients for study groups without and with prior depression

| Model | Prior depression1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor variable | No2 (n = 1610) | Yes3 (n = 1248) | ||

| β | s.e. | β | s.e. | |

| Sub-model for no. of independent life events | ||||

| Age | 0.078** | 0.025 | 0.067* | 0.028 |

| Race, caucasian | -0.022 | 0.025 | -0.069* | 0.028 |

| Sub-model for no. of dependent life events | ||||

| Baseline self-efficacy | 0.040 | 0.026 | 0.022 | 0.032 |

| Baseline depressive symptoms | 0.033 | 0.027 | 0.101** | 0.034 |

| Age | -0.227*** | 0.029 | -0.232*** | 0.033 |

| Marital status, married | -0.084*** | 0.024 | -0.062* | 0.028 |

| Chronic financial stress | 0.192*** | 0.026 | 0.145*** | 0.030 |

| No. of chronic health conditions | 0.073* | 0.029 | 0.009 | 0.032 |

| Sub-model for self-efficacy at follow-up | ||||

| Baseline self-efficacy | 0.371*** | 0.024 | 0.439*** | 0.028 |

| Baseline depressive symptoms | -0.133*** | 0.024 | -0.106*** | 0.030 |

| No. of independent life events | -0.009 | 0.021 | -0.017 | 0.023 |

| No. of dependent life events | -0.014 | 0.022 | -0.076** | 0.025 |

| Age | -0.069* | 0.028 | -0.022 | 0.030 |

| Marital status, married | -0.028 | 0.023 | -0.051* | 0.025 |

| Socio-economic status, upper | 0.078** | 0.025 | 0.076** | 0.028 |

| Chronic financial stress | -0.079** | 0.025 | -0.015 | 0.028 |

| No. of chronic health conditions | -0.081** | 0.026 | -0.096*** | 0.028 |

| Model for symptoms of depression at follow-up | ||||

| Baseline depressive symptoms | 0.300*** | 0.023 | 0.288*** | 0.025 |

| No. of independent life events | 0.046* | 0.020 | -0.006 | 0.021 |

| No. of dependent life events | 0.046* | 0.021 | 0.047* | 0.022 |

| Follow-up self-efficacy | -0.308*** | 0.022 | -0.423*** | 0.023 |

| Age | -0.027 | 0.027 | -0.065* | 0.028 |

| Race, caucasian | -0.065** | 0.022 | -0.048* | 0.022 |

| Marital status, married | -0.066** | 0.022 | 0.028 | 0.023 |

| Socio-economic status, upper | -0.041 | 0.025 | -0.053* | 0.025 |

| Chronic financial stress | 0.044 | 0.024 | 0.013 | 0.025 |

| Functional health status, good | -0.013 | 0.023 | -0.062* | 0.025 |

| No. of chronic health conditions | 0.051* | 0.026 | 0.072** | 0.027 |

The number of dependent stressful life events had a significant, negative, direct effect on self-efficacy at follow-up for the group with prior depression, but not for the group without prior depression. Self-efficacy and symptoms of depression at baseline both had strong, significant, direct effects on self-efficacy at follow-up for both groups. More severe symptoms of depression at baseline were associated with lower self-efficacy at follow-up. Symptoms of depression at baseline only had a significant, direct effect on the number of dependent stressful life events for the group with prior depression. Indices of overall model fit were excellent for the model for the group without prior depression (χ2 14=19.12, AGFI=0.99, RMSEA=0.015) and for the model for the group with prior depression (χ2 14=14.06, AGFI=0.99, RMSEA=0.002).

DISCUSSION

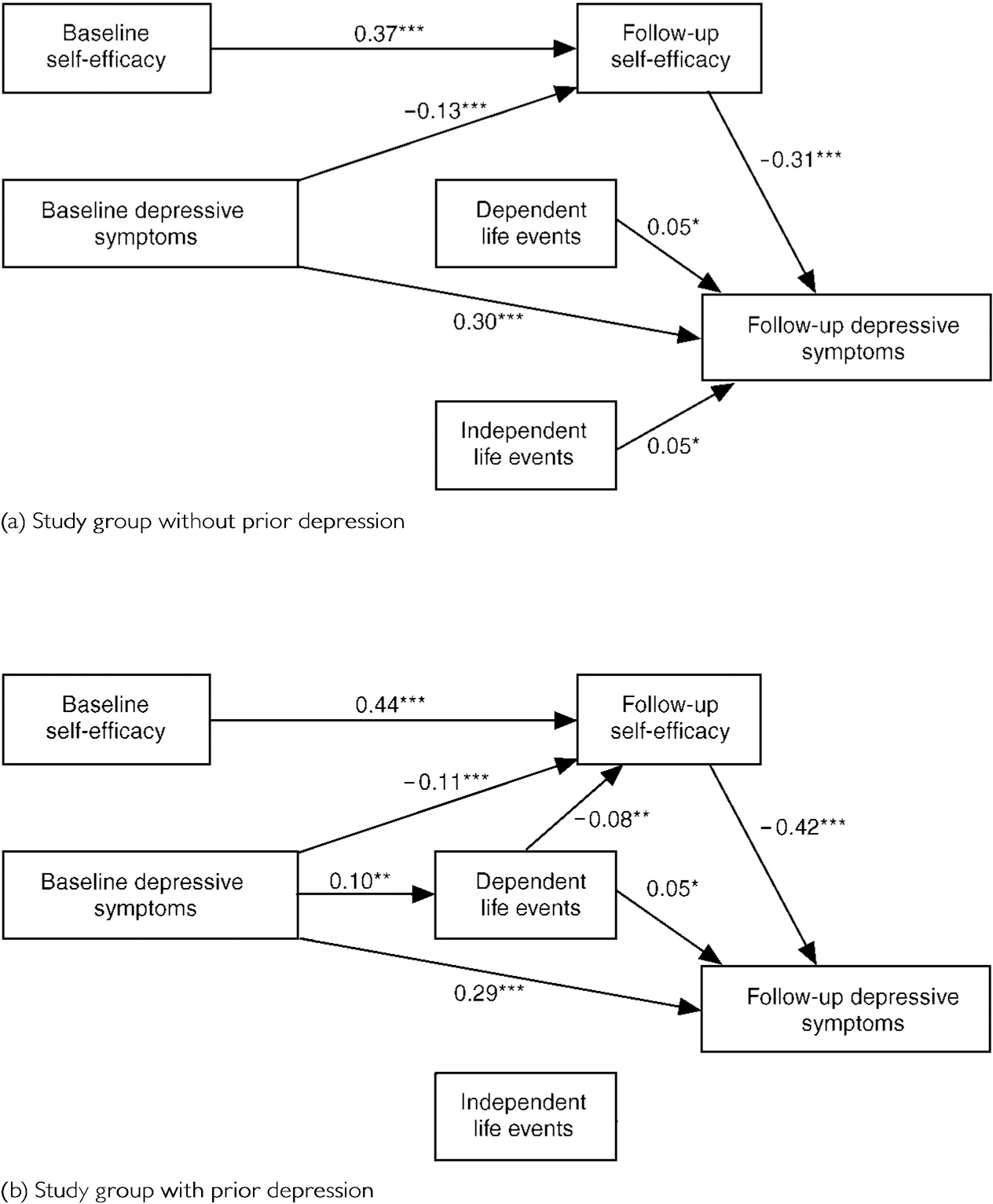

Figure 1 was constructed from the results of our path analyses (presented in Table 2) to facilitate our discussion of the significant interrelationships between self-efficacy, stressful life events and depressive symptoms.

Fig. 1 Interrelationships between self-efficacy, life events and depressive symptoms for study groups (a) without and (b) with prior depression (depressed for a period of at least one week some time prior to the baseline interview).

* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. Only statistically significant paths are shown. Complete results are presented in Table 2.

The significance of self-efficacy in relation to depression

In agreement with earlier studies reporting significant effects of context-specific measures of self-efficacy on symptoms of depression in narrowly defined populations, we found that a more global measure of personal efficacy was a strong, significant, negative predictor of symptoms of depression in a sample representative of the US population. For each of our study groups — those with and without prior depression — higher levels of self-efficacy predicted less severe symptoms of depression. Indeed, the impact of self-efficacy on depression was so strong that the indirect effect of self-efficacy at baseline, as mediated through self-efficacy at follow-up, had a significant impact on symptoms of depression assessed three years later, controlling for the effects of a wide array of potentially confounding factors.

Our path models also suggest that there is a dynamic interplay between self-efficacy and symptoms of depression, which operates over time. In both of our study groups, greater self-efficacy at baseline significantly predicts less serious symptoms of depression at follow-up, and more serious symptoms of depression at baseline significantly predicts poorer self-efficacy at follow-up. It appears that efforts to establish and maintain a sense of control over one's life and environment might serve to build a certain degree of resistance to subsequent symptoms of depression, while periods of depression might undermine these efforts.

Self-efficacy as a mediator of the effects of stressful life events on depression

For individuals with prior depression, dependent stressful life events not only had a significant, direct effect on their symptoms of depression, but also had a significant, negative effect on self-efficacy. Given that poorer self-efficacy strongly predicts more severe symptoms of depression, the total effect of dependent stressful life events on symptoms of depression (βtotal=0.079) was the combination of the direct (βdirect=0.047) and indirect (βindirect=0.032) effects. In other words, for those with prior depression, only 60% of the total effect of dependent life events on symptoms of depression was direct, while 40% of the total effect was indirect, mediated through the impact of dependent life events on self-efficacy. In contrast, for those without prior depression, dependent stressful life events did not have a significant effect on self-efficacy. Evidently, for the group without prior depression, the effect of dependent life events on symptoms of depression was only direct.

Implications for the aetiology of depression

The interrelationships between self-efficacy, symptoms of depression and stressful life events for those with and without prior depression differed in three notable ways (see Fig. 1). First, consistent with the notion that stressful life events are more likely to occur before first- or second-episode depressions than prior to recurrent depressions (Reference Ezquiaga, Gutierrez and LopezEzquiaga et al, 1987), independent stressful life events had a significant effect on symptoms of depression only for the group without prior depression. For those with prior depression, independent stressful life events had no effect on their symptoms. Second, consistent with the notion that depression makes a person vulnerable to experiencing subsequent stressful life events (Reference HammenHammen, 1991), more severe symptoms of depression at baseline significantly predicted greater numbers of dependent stressful life events for those with prior depression. For those who had not suffered prior depression, depressive symptoms at baseline had no effect on the occurrence of dependent stressful life events. Third, as already noted, dependent stressful life events had a significant, negative effect on self-efficacy for those who had suffered prior depression. For those without prior depression, dependent stressful life events had no effect on self-efficacy.

Taken together, the findings of the present study suggest a spiralling cycle of depression. The cycle begins with a stressful life event, either independent of, or dependent on, the individual's behaviour, triggering depression in someone with low self-efficacy. This episode of depression makes the individual vulnerable to experiencing subsequent dependent stressful life events, which serve to undermine their self-efficacy further. This, in turn, makes them vulnerable to subsequent depression, which predisposes to additional dependent stressful life events, which continue to undermine their self-efficacy. The result is yet another episode of depression, and the cycle continues.

Future directions

The impact of dependent stressful life events on self-efficacy and depression among those with prior depression may be closely related to the effects of explanatory style on depression (Reference Peterson and SeligmanPeterson & Seligman, 1984). If a connection can be demonstrated between style of causal attribution and self-efficacy in response to dependent stressful life events, then efforts to build an optimistic explanatory style may prove to be an effective means of maintaining higher levels of self-efficacy in response to these events. In this case, such efforts might diminish the psychological consequences of dependent life events and reduce the risk of subsequent depression. This may prove to be particularly important for women, whom we found to be significantly more likely to have had prior depression, and who had significantly lower levels of self-efficacy.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ Those with low self-efficacy are at risk for severe symptoms of depression.

-

▪ Efforts to establish and maintain higher levels of self-efficacy may serve to build up a long-term resistance to symptoms of depression in the future.

-

▪ For those with prior depression, efforts to enhance self-efficacy following stressful life events, perhaps through cognitive—behavioural psychotherapeutic techniques, may reduce the severity of subsequent symptoms of depression.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ The design of the study was restricted to the number (two) and timing (three years' separation) of the waves of interviews available in the Americans' Changing Lives study.

-

▪ The assessment of life events was restricted to a simple inventory.

-

▪ The results are restricted to symptoms of depression.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.