In April 1939 a small Polish publisher released Capitalism, a booklet ambitiously advertised as part of ‘a new socialist literature’ about the ‘present-day world order’. Capitalism was essentially an obituary for a ‘system that clearly failed’. The author, writing under the pseudonym Wacław Lipski, argued that the Great Depression constituted ‘a death sentence’ for capitalism because it was state intervention – state-led economic planning and large public works – and not the capitalist economy’s self-healing ‘automatism’ that had helped nation states to recover from the crisis. Capitalism’s failure was most apparent in poor agrarian countries that ‘had mostly experienced its dark side’. In Asia, Africa or in agrarian Southern and Eastern Europe – the frontiers of the capitalist economy, what the author vehemently described as the ‘wilderness of capitalism’ – a few foreign investors, ‘unscrupulous gamblers’, would circulate in search of quick, easy profits. They would exploit the hopes of ‘backward countries’ to modernise but would provide no more than very low wages for very few.Footnote 1 Capitalism discussed a world’s poor majority that after the shock of the Great Depression arrived at a political and economic crossroads. In this ‘dangerous zone’, in which Lipski included Poland, where even the few reckless investors had stopped investing, capitalism held no future, Lipski argued. This future had yet to be invented and economic statistics served as a tool.

Poland, where Capitalism was written, itself occupied not only a political but also an epistemic crossroads. I argue that in the interwar era of political economic experimentations that paved the way to a conception of international development, Poland was understood as liminal space from which one could observe the richest and poorest countries while maintaining a position equidistant from both.

Capitalism’s author’s real name was Ludwik Landau (1902–44). Landau was one of the chief economic statisticians in interwar Poland and a well-known figure in the Polish-Jewish circles of the socialist intelligentsia. This article examines the aspect of his scholarly and activist work which empirically investigated Poland’s predicament in the framework of world capitalist economy. Like many other Central and Eastern European Marxists, Landau saw Poland as a dual landscape of underdevelopment – islands of urban centres with modern factories surrounded by a sea of small towns and villages full of ‘primitive workshops’ and self-sufficient farms.Footnote 2 Writing from a perspective of ‘backward’ Eastern Europe, Landau was a pioneer in international developmental thinking: his belief that Poland’s dual economy could be projected and conceptualised on a world scale is perhaps his most important insight, and why he and his work still matter. Landau measured the global gap between rich and poor countries in 1938–9, when such a synthetic view was still largely unimaginable.Footnote 3 His most ambitious monograph, World Economy: Production and Social Income in Numbers, published at the same time as Capitalism, was a scholarly elaboration of his socialist views on the necessity of non-capitalist development for Poland and other poor countries.

This particular blend of politics and science, Marxism and statistics demonstrates how the key scholarly innovations in interwar Poland emerged on the margins of academia, the state and state-appointed experts’ international cooperation. Like many radicals with professional careers in the tsarist Kingdom of Poland and, later, under the Polish Sanacja’s authoritarian rule (1926–39), Landau led a kind of double life.Footnote 4 Because of this he remained a man of mystery, whose voice must now be recovered in an indirect and circumstantial fashion.Footnote 5 Landau’s statistical work for the Central Statistical Office and several Warsaw social research institutions lacked explicit references to Marxism, but under pseudonyms Landau published anti-capitalist critiques in which fierce – even revolutionary – rhetoric often supplanted numbers. Unlike much recent literature, which focuses on Eastern European iterations of racialised or nationalist science often sponsored by the ruling elite, this article concerns scholarship that embraced the world scale to challenge the world economic and political order and Poland’s national policies.

Landau’s liminal position is inextricable from the all-encompassing historical rupture that Eastern Europe experienced in the mid-twentieth century. As the militancy of the 1930s turned into mass violence, many interwar intellectual projects were interrupted or left incomplete. In 1939 Ludwik Landau predicted, with remarkable accuracy, that the future of development policies would be decided in a military–ideological confrontation between ‘fascism, communism and social democracy’. Had his work been translated and had he survived the Holocaust, World Economy easily could have competed with a similar work written two years later by Briton Colin Clark, a close collaborator of John Maynard Keynes.Footnote 6

Landau’s limited reception and the content of his scholarship lead to questions about the status of politically ‘peripheral’ localities in the history of science. Similar views cropped up in other such ‘peripheral’ places. In the 1930s statistically minded scholars from colonies or small Eastern European nation states, such as Zarik Hussain in British India and György Matolcsy and Mihály Varga in Hungary, also argued that statistical economic research should reveal material disparities and patterns of exploitation.Footnote 7 Generally, Landau’s work participated in a worldwide movement of reformers and radicals on both left and right who, after the First World War, contested the existing international order and pleaded for structural change. If Carol Gluck is right in claiming that ‘history of elsewhere is everywhere now’, because ‘the appeal of the modern’ was co-produced worldwide,Footnote 8 then this and other Eastern European histories of science should be taken seriously.

However, as Roger Chartier argues, knowledge from ‘elsewhere’ still must be placed in the context of the asymmetrical, albeit historically shifting, power relation with Western science. In the framework of domination, the quest to study knowledge’s circulation should not cause us to forget that the science from ‘elsewhere’, though it mattered ‘everywhere’, was regularly silenced or subjected to restricted transfer and public visibility. A realistic assessment of the global history of science must acknowledge that much of world knowledge production existed primarily as what Chartier names ‘limited possibility’.Footnote 9

Landau saw his homeland as a starting point from which to explore underdevelopment globally. His work also reflected a broader trend among interwar scholars to seek routes out of the omnipresent crisis – political, economic and demographic – by making forceful, world-scale arguments.Footnote 10 The quest for a global framework must be understood in the context of the interwar moment of ‘deglobalisation’: imperial and national protectionism, tight restrictions on international money lending, and increases in anti-migration policies.Footnote 11

This article opens by describing Warsaw as a centre of the social statistics that in the mid-1920s became Ludwik Landau’s main field of expertise. While progressive statistics shaped Landau’s intellectual background, he also drew from the burgeoning international field of market research. Combined and reconfigured, statistics and economics became a tool of anti-capitalist critique. Additionally, Landau’s politically engaged research raised the issue of commensurability between ‘civilised’ and ‘backward’ regions. In his comparative statistics and the seminal World Economy, Landau addressed how the world’s cultural unity and diversity could be quantified in a single framework. The article concludes with a discussion of the political and epistemic significance of Landau’s work and how it figures in the larger history of development and statistical measurements of the world.

Progressive Statistics in Warsaw

Although often described as an ‘independent thinker’, Ludwik Landau’s progressive approach to statistics clearly descends from an understanding of statistics as a broad discipline about ‘social structures’ of the modern world – communities, societies or national economies – an understanding prevalent in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.Footnote 12 Warsaw-based socialist scholars, including Landau, reconfigured academic statistics – the science of mass-scale social interconnectedness and economic relations, as this section demonstrates. By combining it with Marxism they set the agenda for progressive and developmental statistics from then on.

Interestingly, Landau learned structuralist approach to statistics from socially conservative and nationalist professors. In the Law Department at the University of Warsaw, where Landau studied in the early and mid-1920s, statistics was based on German textbooks on ‘the science of the state’ (Staatswissenschaft).Footnote 13 Landau’s teacher and mentor Antoni Kostanecki, influenced by the German Historical School, claimed that what he called ‘social economy’ was a ‘common good’, in which nationhood and middle-class property were central values – values intended to counterbalance both classic political economy’s individualist perspective and Marxist thinkers’ materialism.Footnote 14 ‘Marx’s Capital’, Kostanecki lectured Landau’s class, ‘is an objectivist and cosmopolitan creation through and through’.Footnote 15 Kostanecki’s stress on national character’s importance gripped some of Landau’s fellow students. In the early 1920s radical Polish nationalists set up ‘Jew-free, Aryan-only’ public spaces in student houses and fraternities.Footnote 16 Landau evidently listened only selectively to his professors. As a non-religious assimilated Jew appalled by virulent nationalism, he became committed to precisely that Marxist cosmopolitanism derided by Kostanecki.

To engage with less nationalist political and scholarly views on statistics Landau needed to venture outside the University of Warsaw. He found just such an intellectual environment in the Central Statistical Office (Główny Urząd Statystyczny; GUS), which he joined in 1923. Established in 1918 as a symbol of Poland’s newly acquired statehood, GUS was not just a central administrative institution to create a statistical inventory of the Polish state but also a haven for the socialist intelligentsia. Because the new Polish state was short of educated elites and sorely needed people who could prepare the first general census, in 1921, as well as process the results, GUS quickly became a space of asylum for political outsiders. In the early and mid-1920s left-wing activists and professionals with Jewish backgrounds like Landau filled the institution. It was also the biggest public employer of educated women. Many of these employees were members of the socially engaged youth learning statistics in an ad hoc manner.Footnote 17

The socialist intelligentsia gravitated naturally toward labour statistics, which dealt with the living conditions of the industrial working class. It comprised a wide range of topics: wages, employment, strikes and lockouts, the prices of consumer goods, housing and industrial production and work migrations. Sometimes called ‘occupational’, ‘social’ or ‘economic’ statistics, Polish labour statistics of the 1920s reflected left-wing sensibilities; it was a projection of the local intelligentsia’s hopes for modern – that is, welfarist and progressive – Poland. At GUS Landau interacted with two generations of socialist statisticians, including senior Marxist scholars, who co-created the General Census of 1921 and shared their experiences with younger colleagues.Footnote 18 It’s not known whether Landau belonged to one of the informal reading groups that gathered young and old Marxists employed at GUS, but widespread commitment to Marxism was an open secret within the institution and Marxism permeated some of its major works. For instance, a major GUS publication from 1925, which Landau may have read, averred that statistical tables were ‘markers of mass-scale social transformations’: statistics recorded the oppressed majority’s predicament. The publication argued that statistics was a more powerful form of knowledge than history or literature because it showed ‘the tragedy of the peasant not through an individual story but rather in his millionfold mass’.Footnote 19

Marxist-minded statistics was unabashedly forward looking and critical of the official administrative statistics that the state had inherited from the imperial era. Marxist-minded statistics also possessed a developmental and progressive agenda and advocated a class-based perspective on social life. One of the 1921 census’ authors, Marxist intellectual Henryk Grossman, explained in an official memo that the census aimed to ‘initiate an investigation of structural features of Poland’ and thus to form the ‘basis of any kind of inquiry about various directions that social life could take’.Footnote 20 As his unpublished lectures and writings show, he endorsed a direction leading to a socialist welfare state.Footnote 21 However, dreams of transforming statistics into a reformist, even revolutionary, force had to wait. The violent course of the 1921 census, a militarised operation in a country ravaged by recent wars and consumed by inter-ethnic tensions, was a wake-up call for progressive statisticians. They realised that Poland’s population, particularly peasants and residents who were not ethnically Polish, did not trust census commissioners. In fact, census taking was widely perceived as a tool of yet another occupying state power, a means of requisitioning food and livestock or a force of ‘denationalisation’. Grossman interpreted this failed census through a Marxist lens, asserting that it signified ‘the popular struggle against statistics and the liberal state’. Popular hostility toward statistics would prevail ‘as long as capitalism existed’.Footnote 22 Progressive statistics strove to create numerical knowledge to foster social and economic development, but to accomplish this goal, Grossman wrote, it needed to break with its ‘fiscal past’ and focus on improving the working population’s lives. In other words, statistics needed to become knowledge not only about, but also for, the masses – science under the banner of socialism.Footnote 23

Sympathetic to progressive statistics, Landau quickly incorporated Marxism to the meta-language of social structure to study issues of capitalist development. To do that Landau borrowed heavily from two major structuralist social thinkers of the nineteenth century, Karl Marx and Max Weber, who used the conception of social structure to explain the developmental status of states and communities. Marx claimed that ‘the sum total of relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society’,Footnote 24 while Max Weber talked about ‘socioeconomic structures’ that the capitalist economy transformed one after another.Footnote 25

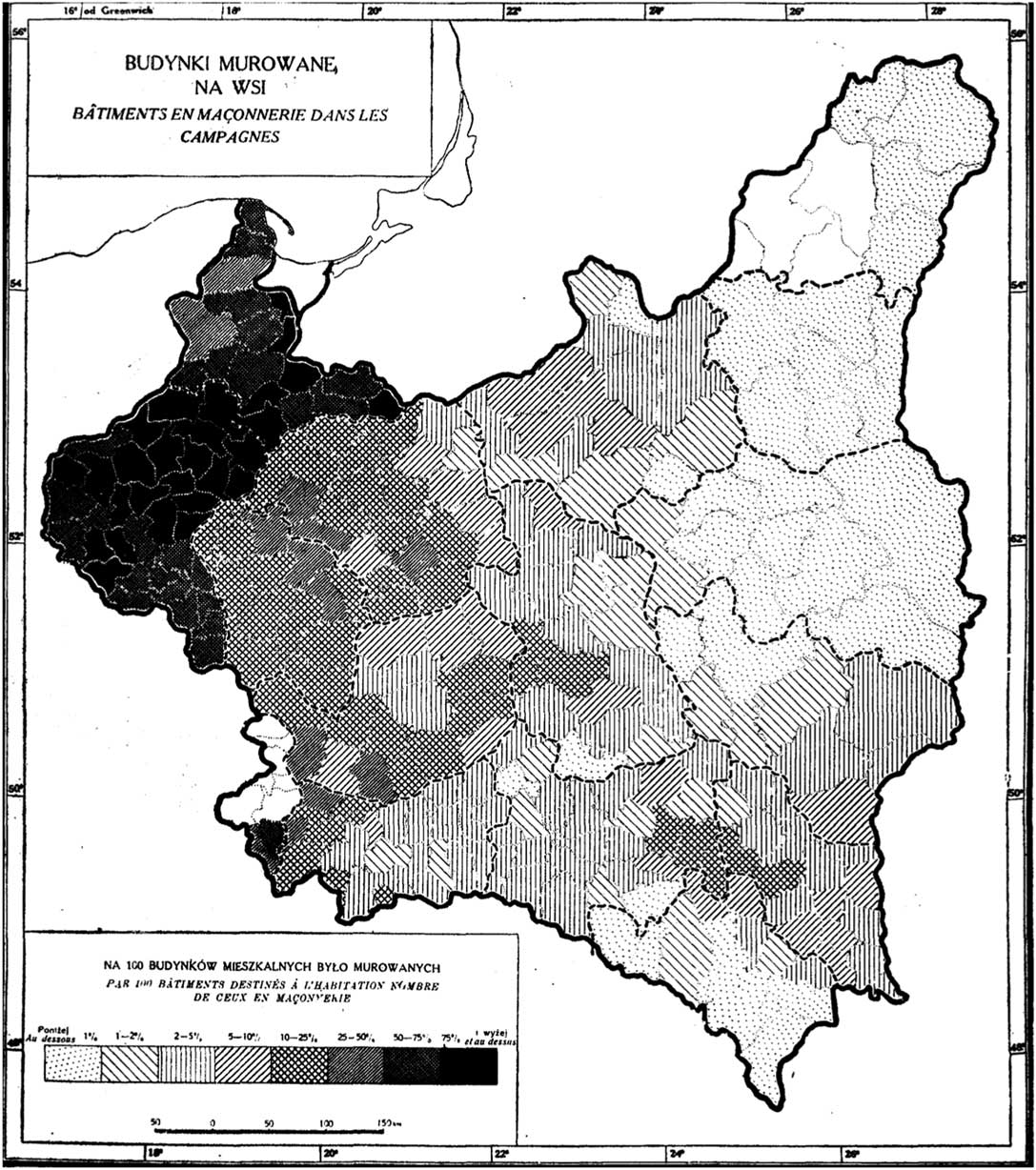

Landau transposed these currents to descriptive, administrative statistics. His first major assignment was a statistical map, based on the 1921 census results, of Poland’s dwellings. As an inventory it showed a Poland with large differences in material conditions. The map revealed how past partitions engendered civilisational discrepancies between former Prussian, Austrian and Russian provinces. The map was a study in contrast: brick houses in the west and wooden huts in the northeast. It made visible, for the first time, Poland’s uneven economic conditions at one glance (see the map on the following page).Footnote 26

Poland as a ‘Capitalist’ Country

From the late 1920s Landau would spend another decade attempting to better understand the economic and political significance of his map of Poland’s material disproportions – between West and East, between the country of brick and country of wood. At GUS he gained his first professional experiences, and the combination of progressive statistics and German structuralism predominating in GUS’ left-wing circles gave him a methodological foundation and an ideological compass. But it was a new branch of economic statistics – research into markets and business cycles – that spurred Landau’s focus on studies concerning world capitalism. After 1918 market fluctuations research, developed at Harvard University and energetically promoted in Europe by the Rockefeller Foundation, expanded rapidly across the northern Atlantic world. It was embraced in Poland with the goal of using expert knowledge to modernise Poland’s export policy. In 1926 Edward Lipiński, a senior economist at GUS, asked Landau to help implement US-style market research in Poland. Landau, eager to learn about what was then cutting-edge social science, accepted.

Although his avowed goal was to apply foreign research models in a Polish context, Landau’s engagement with research on market fluctuations differed greatly from the original US model. Landau gave the US approach a structuralist twist to revise the implicit assumption that Wall Street corporatist capitalism was applicable in Polish conditions. He was also much more sceptical than the Americans about the ease of managing capitalist markets.Footnote 27 Landau’s approach and position would enable him to develop a statistical conception of Poland as a ‘half-capitalist’ country. It would also help conceive of Poland as a useful site from which to study the ‘dark side’ of capitalism in poor countries.

Ludwik Landau, Pierwszy Powszechny Spis Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej z dn. 30.IX.1921: Budynki: Analiza (Warszawa: Główny Urząd Statystyczny, 1928), 1–51, the map of brick buildings, 24.

In the late 1920s Landau’s career accelerated. In 1927 he joined a working group established within the GUS’ Department of Labour Statistics that focused on market fluctuations. Just a year later, when the Institute for the Study of Business Cycles and Prices (Instytut Badań Konjunktur Gospodarczych i Cen; IBKGiC) was founded, Landau became its head of economic research.Footnote 28 As in other European countries adopting US-style liberal market science, the Polish government expected the Institute to develop tools that would help predict what is today called ‘market behaviour’. The Americans believed that although both upswings and crises, booms and depressions characterised a capitalist economy, its fluctuations were predictable – and thus controllable. In other words, a capitalist economy’s inherent disadvantages could be offset through economic science and statistical measurements. Landau’s team was tasked with estimating and forecasting – using the so-called ‘Harvard barometer’ – the dynamics of Poland’s industrial production in a ‘regular and predictable time-series’.Footnote 29

However, it was immediately evident that US techniques for measuring market phenomena failed in the Polish context. For instance, Poland lacked a national stock exchange, which, according to Americans, constituted the heart of economic life. Further, the American model assumed that markets could be observed and understood by attending to, and noting, the ‘free movement’ of prices, but such movement did not occur in Poland, where cartels and the state dictated the prices of key export products such as oil and coal. More importantly, the majority of Poland’s population resided in villages, towns and shtetls, so most had little contact with the modern capitalist economy. Cash was a rarity in the Polish countryside, and its ‘markets’ – weekly bazaars selling local produce – were entirely different from a Wall Street-style stock exchange. Landau soon concluded that US methods could analyse and represent only a thin slice of real economic life in Poland. Landau’s central question was not how to gauge a capitalist market statistically, as this type of market constituted only a small part of Poland’s national economy. Rather, Landau questioned to what extent capitalism manifested in Poland’s economic life at all.Footnote 30

To understand what ‘capitalist economy’ signified in the Polish context, Landau’s team linked the concept of the market with the statistical concept of structure. They aimed to study the two in relation to one another: numerical renderings of business activity made sense only if placed only within the specific historical, economic and social settings in which the activity occurred.Footnote 31 The Polish team also assumed that capitalism was global, meaning that capitalism affected, in one way or another, all the regions of the world. Nonetheless, the unity of capitalism did not negate its diversity. Polish economic statisticians adopted the German Historical School’s position that the world economy has a ‘structure and rhythm’ that varies from country to country.Footnote 32 In World Economy Landau expressed this clearly: ‘economic life is governed not only by market fluctuations, but also by long-term developmental tendencies’. To understand the developmental path of each country it was important to assess when and how the country ‘entered the orbit of capitalist world’. According to Landau this determined whether, throughout history, the country would become wealthy or poor, coloniser or colonised, exploiter or exploited.Footnote 33

Further, the Polish team applied a Marxist lens to their research on markets by presenting market activities as sociological (relational) and thus implicated in class politics. Echoing Friedrich List’s famous statement that ‘what is economically good for an individual may not be good for the nation’, Landau and his team claimed that the ‘state of the market could be “good”, while the state of the mass population could be bad (though the reverse is not possible)’.Footnote 34 So by employing a structural approach Landau and his team exposed the political economic significance of research on markets. Their work evidenced the necessity of studying the economic abstractions of ‘market’ or ‘business cycle’ in the context of relations between different social classes and countries, and interrelationships between rich and poor.

Between the late 1920s and the early 1930s Landau’s work swiftly transformed the original US-style research on markets into economic studies on the ‘half-capitalist’ structure of Poland. ‘Half-capitalism’ did not mean solely that the Second Polish Republic was a semi-industrialised country; Landau also stressed that huge socioeconomic disparities characterised a ‘half-capitalist economy’. Wages in large urban centres contrasted sharply with those in rural areas. As Landau wrote in 1933, ‘small, primitive workshops’ run by craftspeople, shopkeepers and peasants ‘could compete with big industry only by keeping wages very low’. He added that these factors aligned Poland with ‘all countries that lacked investment capital and did not have modern industry able to absorb the whole workforce’.Footnote 35 This formed the essence of Landau’s studies on ‘half-capitalism’: Poland, structurally speaking, was a miniature of the world. This insight led to his world scale comparisons.

In 1931, to give a sense of economic shortcomings and the exploitative nature of the ‘half-capitalist economy’, Landau conducted a pioneering study on Poland’s occupational structure, a study that produced the first estimations of Poland’s social income. Marxist statisticians reasoned that class occupational structure was the best way to represent the ‘economy’ because it directly revealed wealth’s societal distribution. Landau therefore broke down such aggregate categories as ‘farmer’ into the subcategories of ‘peasant’ and ‘landowner’, and divided industrialists into upper-middle class merchants and petty tradespeople.Footnote 36 The prominent Polish economist (and IBKGiC member since 1929) Michał Kalecki, who along with Landau computed the social income of Poland in 1933, stated that this ‘study was probably the only attempt in the capitalist world to make a detailed distribution of national income according to social classes’. While interwar economists moved away from distributive understanding of national income, Landau returned to the nineteenth-century class-based concept of the living standard. Class analysis of ‘economy’ enabled him to assess something important to left-wing activists: the extent of poverty.Footnote 37

The Great Depression’s disastrous effects in Poland and other agrarian countries only advanced this critique. In 1932 Landau and other left-wing economists began to write for Przegląd Socjalistyczny, a revolutionary journal oriented toward the intellectual left. Both Kalecki and Landau began to voice their anti-capitalist critiques more openly. Kalecki, an avid reader of Rosa Luxemburg, shared her conviction that world capitalism was ‘inherently chaotic’.Footnote 38 This statement stood in clear contrast with the official ideological position of the IBKGiC. Just before Landau and Kalecki officially announced that Poland’s income had dropped by 37 per cent since the beginning of the crisis,Footnote 39 Landau, writing in Przegląd under a pseudonym, described the global economic crisis as ‘a catastrophe’ that showed the ‘evil of capitalism’.Footnote 40 Landau also stated that the division of social income under capitalism did not provide or ensure mass welfare, while socialism would, at least in theory. In this way, Landau introduced himself as an anti-capitalist thinker, and, as Oskar Lange, another contributor to Przegląd Socjalistyczny, stated, ‘the bridge for the progressive intelligentsia to anti-capitalist critique and to the Popular Front’.Footnote 41

Challenging the Double Standard in World Statistics

The Great Depression’s unprecedented severity hastened the rise of radical politics in both the Western and non-Western worlds. In the latter economic meltdown manifested as agrarian crisis, often accompanied by starvation. A sense of urgency arose around addressing poverty on a global scale, but this new effort also exposed widespread scholarly ignorance concerning living conditions outside the industrialised West. In Landau’s case, his studies on ‘half-capitalist’ Poland alerted him to a Western-centric myopia extant not only in the up-and-coming business-cycle research but also in the established field of administrative statistics. The industrial capitalist economy acted as an implicit model in existing international standards of statistics and Landau recognised that these scholarly conventions excluded vast areas from statistical representation. In Poland, unlike in some countries like France, peasants and artisans did not qualify as formally ‘employed’. Internationally, household or smallholder economy did not figure in official employment statistics. Landau’s map of Polish housing conditions provides a useful metaphor: while economic statistics integrated the ‘brick’ modernity in western Poland, but not the ‘backward’ wooden villages in the east.

Emerging during the Great Depression the quest for worldwide data raised – and instantly politicised – the problem of statistical commensurability. Big powers interested in global governance hoped that more statistics would make the global poor more visible.Footnote 42 But the task appeared daunting. In 1934 Eugen Varga, Stalin’s economic adviser and director of the Institute for World Economy in Moscow, agreed that ‘the unevenness of development in various countries’ required serious analysis but admitted that it was easier to study problems theoretically rather than according to geographic regions.Footnote 43 And in 1931 British colonial administrators, although anxious to institute economic reforms in their colonies, failed to improve comparability in the Imperial Census, which was one of the key tools of colonial governance.Footnote 44 When, by the mid-twentieth century, no ‘one statistical world’ yet existed, the causes were epistemic and cultural as well as technical.Footnote 45 We can see this by examining the comparativist dimension of Landau’s work, which consciously challenged the standards of international statistics to pursue studies of poor, agrarian countries on a world scale.

In the 1930s Landau also became a noted specialist in international comparative statistics – although, oddly, he went abroad only once: to Geneva in 1931 as the Polish delegate to the Committee on Statistics of Living Costs and Wages at the International Labour Office (ILO).Footnote 46 Well-versed in English and German, he already possessed a good understanding of the international literature on statistical comparisons. In Geneva, however, he discovered that most of the data about non-European world regions collected by the League of Nations was systematically set aside. If these numbers were published at all, it was as unprocessed material, or what Landau called ‘loose statistical tables’. Landau could easily imagine the motivating factors: according to the statistical ideal of exactitude in which he was trained, one could publish only data that was – as far as possible – complete and precise. The ILO’s loose statistical tables containing information about agrarian eastern Europe, Asia and Africa did not meet this standard. Thus, the data were excluded from international comparisons.

For Landau, Geneva’s key lesson was that statistics, when applied on a global scale, was systematically founded on a racialised double standard. According to the late nineteenth-century German statistical textbooks still ubiquitous in interwar Warsaw and elsewhere in Europe, statistics could be split into an ‘exact science’ (exakte Gesellschaftslehre) when concerned with white ‘advanced’ nations and ‘estimations’ (Orientierungswesen) when concerned with non-industrialised territories, colonial peoples and nomadic tribes.Footnote 47 German statisticians argued that exactitude was a unique virtue of ‘cultured nations’, while estimations were a lesser kind of knowledge. Further, statistics emanated from civilisational advancement because ‘the sense of quantitative observations develops only very late, in the highest stages of human development’.Footnote 48 The British shared the Germans’ view that human ‘statistical masses’ (nations, peoples, tribes) represented various degrees of human development and, in fact, were incomparable. As Robert Giffen, a well-known British colonial statistician, wrote in 1904, ‘the peoples of Europe and the United States are, as a rule, of very different value from the units of population in Hindoo, Chinese, negro, and aboriginal communities. . . . Statistics of population has to be then discussed with reference to the quality of the units’.Footnote 49 The statistical ideal of exactitude, like the entire Western ideal of science, was thus deeply racialised and racist, a characteristic that determined the divergences in how statistics operated in the Western and non-Western worlds.Footnote 50

This racialised ‘double standard’ statistics arose from a self-contradictory ideology. Colonial statisticians claimed that reliable numbers could be produced in colonial and remote territories only through the expansion of modern European administration. However, colonial administrations were often vague, imprecise and oversimplified when collecting data on native populations. For example, colonial statisticians in Algeria applied elaborate statistical nomenclature when describing French colonists but classified the ‘indigenous’ population as Muslims, an outdated category of religious affiliation that metropolitan France ceased to use in 1871.Footnote 51 During the interwar years British officials in Africa continued to run separate ‘non-native’ and ‘native’ censuses, despite attempts by reformers to change this practice. South Africa delayed the 1931 Imperial Census by five years and then counted only the white population.Footnote 52 The British progressed only with statistics of trade and production, perhaps because in the late colonial era resource extraction still mattered more than the indigenous population’s living standard.Footnote 53

Landau used the fragmented data from South Africa to execute his first cross-continental comparisons. In a short article from 1930 based on ILO’s unclassified materials, Landau showed how he estimated international differences between wage levels in coal mining. This example reflects the essence of Landau’s other statistical comparisons, which eventually enabled him to construct a synthetic view of global inequalities.Footnote 54 His 1930 research included Canada, Japan, the Union of South Africa, India, England and Upper Silesia (Poland’s industrial region). When discussing South African mining statistics, Landau distinguished between ‘natives’ and ‘whites’ to demonstrate that ‘whites’ earned approximately fifteen times more than ‘natives’. Characteristically, Landau did not provide absolute values for wages, instead presenting their relative, proportionate worth. Using this structuralist approach, he estimated the global proportions between miners’ pay in various countries, from India (1,30) through Upper Silesia (5,37) to England (13,73) and other countries. Landau also distinguished between wages for aboveground and underground work; underground workers were better paid.Footnote 55

Whether a study investigated coal production in the Polish economy or the world’s, what truly mattered was apprehending the structure, not the magnitude. Instead of reproducing racialised statistics, Landau aimed to change statistics’ meaning to stress the scale of labour exploitation based on race and politico-geographic conditions.

Landau’s approach was unique internationally. For instance, authoritative German statisticians who processed the same South African data did not differentiate between white and non-white workers and provided information only on the average wage.Footnote 56 For Marxists like Landau, the idea of ‘the average’ constituted a major evil in economic statistics because it obscured the internal – inevitably antagonistic – relationship between haves and have-nots. ‘Calculating indices of average-per-head in class societies is fundamentally fictitious’, wrote Landau’s student, economic historian Witold Kula.Footnote 57 In turn, the epistemic imperative behind Marxist-minded statistics aimed at revealing inequalities on each level of social research, from factories to one world economy.

Toward a Global Statistics of Non-Capitalist Development

In the second half of the 1930s the scattered studies Landau conducted on social income, Poland’s economic structure and comparative statistics coalesced into a more coherent conception of the world economy. In those years Landau typically projected his research on Poland outward, in order to talk about capitalism globally. Conversely, he used international comparisons to emphasise that depression-era capitalism hindered economic development in poor countries like Poland. In the 1936 Welfare Program, co-authored with Marek Breit for socialist trade unions, Landau represented Poland as a country of ‘screaming [social] injustices’. He also wrote that ‘capitalism, on a global scale, enabled some countries to have a higher standard of living at the expense of other countries’. Structurally speaking, Poland and the majority of the global population were hostages of the same capitalist order, which, he and Breit argued, ‘needed to be replaced’.Footnote 58 Landau’s World Economy, written two years later, described the ways in which its global scope acted as an argument for a bold, non-capitalist approach to Poland’s development.

Thus, Landau’s statistical investigation of the world economy strove not only to describe the status quo but also to argue statistically about how to alter it. In the Poland of the late 1930s this developmental perspective seemed radical because liberal economics held strong in Polish expert circles and few imagined that state interventionism could be expanded countrywide. More importantly, the Polish government and integral nationalists believed that the primary solution to Poland’s predicament was the mass emigration of ethnic minorities – Jews in particular. The ‘Polish economy’ was too small, nationalists argued, to contain the ‘Jewish economy’; Jews were therefore deemed superfluous.Footnote 59 The Polish military and political elite hoped that industrial investments would improve national security and create better paying industrial jobs, reserved for ethnic Poles. Against these dominant ethnonationalist views, Landau advocated radical change – socialist, state-led industrialisation – to increase Poland’s economic potential and provide jobs for everyone, irrespective of ethnic background. This attitude earned him many enemies. In May 1937, following incessant rumours that the Institute for Research on Business Cycles was a ‘Judeo-communist unit’, Landau and Breit were dismissed (officially for writing a report critiquing the government). Despite anti-Semitic attacks on him by the Polish right-wing press, Landau returned to the GUS as head of the Social Statistics Division.Footnote 60

In the sole English-language review of Landau’s work, Michał Kalecki wrote that World Economy charted ‘an entirely new route’ in economic research. The book was a somewhat dry 151-page monograph, but it showed, for the first time, what structurally distinguished ‘economically developed and underdeveloped countries’ on a world scale.Footnote 61 It contained sixteen statistical tables that took Landau nearly a decade to compute. The tables presented comparative data on productive activity – including industry (from 1929) and agriculture (from 1926–9) – in various countries, data drawn from existing international statistics on manufacturing, foreign trade and labour. Perhaps the work’s most valuable element was that this data also served as a tool for estimating social income in uniform world prices. Uniform world prices functioned as a ‘common denominator’ – the actual world scale – by which material distances between countries were revealed.

Landau classified countries according to their ‘occupational structure’ (the degree of the population employed in industry) and ordered them from most to least developed. At the top he placed ‘industrial Europe’, then ‘countries with an intermediary structure’ (Japan and Italy), then ‘agricultural Europe’ (including Poland) and ‘agricultural overseas countries’. As the only country to have exited the capitalist system, the Soviet Union was excluded from the comparison. Landau explained that the book’s intention was to show Poland’s ‘career’, as he somewhat sarcastically called Poland’s place in the world economy, in relation to other countries and world regions. It also focused on Poland’s prospects if this ‘career’ continued to be capitalist.Footnote 62

The entire statistical investigation was a one-man show created without institutional support, and Landau acknowledged the endeavour’s riskiness. While international data on industrial production – available through the League of Nations’ statistical services – was fairly reliable, available statistics on global agriculture was highly fragmented.Footnote 63 Agriculture, then the activity dominant among world’s non-white population, fell victim to racialised dogmas in statistics, and so was neither ordered nor summarised. However, Landau was determined to provide a synthesis. He emphasised that the main reason was not his ambition to ‘embrace the whole’. Rather, he was principally motivated by his belief ‘that exotic countries’ – Africa, Asia and most of Latin America – ‘are particularly interesting from our point of view, as their level of development is close to the level of development of agrarian European countries’.Footnote 64 He explained this in characteristic Marxist fashion: ‘the most glaring inequalities occur, when we shift our attention to rural populations and social groups related to them – handicrafts, village and small town trade, etc. Peasants (as well as craftspeople or small shopkeepers) of agrarian countries of Europe are in exactly same position as the natives from the strictly colonial countries.’Footnote 65

Methodologically, World Economy was an exercise in audacious estimations. Landau did attempt to collect as much data as possible, digging into statistical yearbooks from Germany to China, but he often used extrapolation, a trick employed by statisticians confronted with a lack of data. In practice, this meant that in World Economy the statistics of Morocco was extrapolated for the entire Maghreb, and that to estimate Chinese tea production Landau used and manipulated available figures from other East Asian countries he judged to have similar economies of tea cultivation.Footnote 66 Moreover, what Michał Kalecki called ‘a heroic work in data collection’ had serious blind spots. Landau excluded women’s labour (both professional and domestic), arguably because female work was seldom classified in international statistics. He also excluded services and trade and reduced family enterprises to one-person male work. His World Economy represented the gendered socialist (and communist) ideal of a worker: the male physical labourer toiling either in a factory (Landau focused on mining) or on a plot of land.

Despite these exclusions, Landau’s World Economy was nonetheless revelatory, even if his conclusion may seem obvious today. First, Landau presented huge disparities – demonstrated in numbers – between ‘underdeveloped’ and ‘developed’ societies as primarily material, even though they conveyed cultural assumptions about what makes material civilisation ‘advanced’ and ‘underdeveloped’. Still, his quasi-materialist interpretation denounced cultural essentialism and racism. Further, he concluded that the standard of living and degree of economic development depended on two factors: the advancement of capitalist industrialisation (again, the Soviet Union was a separate case) and the percentage of the population working in agriculture. Landau demonstrated that agrarian countries reliant on smallholder farming and handicrafts, such as China, India or Yugoslavia, were among the poorest, whereas industrial states, including those equipped with highly efficient, mechanised agrarian sectors, like the United States, were wealthiest.Footnote 67 By creating a ‘common denominator’ – standardised prices of production in all countries – he could assess which states or colonial territories were ‘rich’ or ‘poor’ in relation to each other. In Capitalism, the political commentary supplement to World Economy, Landau offered his political message to the poor in Poland and across the globe. Since the Great Depression capital had ceased to flow into poor countries, so the only way to begin to develop was to industrialise like the United States, the top country on the scale. Yet the route to economic development that Landau offered was not a capitalism he believed to be bankrupt but a socialist, planned democratic state.Footnote 68

In 1939 Landau was persuaded that this future would be decided neither through confrontation of political programmes nor by making scholarly argument, but rather in the course of the next global war. In a Marxist fashion, he continued, the ‘superfluous masses’ in poor countries formed a ‘revolutionary element’ that states and empires tried to manage by stirring in them hatred towards other nations or social classes, while promising a better life. Communism and fascism were then two ideologies that sought to conquer ‘agrarian Europe’ and poor countries in general. Poland was in the centre of this ‘dangerous zone’. The political stakes of the war that Landau saw coming were not the preservation of liberal capitalism, but the task of building socialist democracy as a basis of economic development.Footnote 69

Conclusion

The location and year of World Economy’s publication – Warsaw, 1939 – could not have been worse for disseminating Landau’s path-breaking work. At least one copy of the book, owned by Kalecki, made it to the West, but no English translation followed. Meanwhile, in occupied Poland, Landau arranged false ‘Aryan’ papers for himself, his wife and his daughter, changed the family’s surname to Lewandowski and decided, after the initial resettlement of Jews to the Warsaw Ghetto, to move out of the area.Footnote 70 After the violent suppression of the April–May 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising annihilated most of the city’s remaining Jewish community, Landau conducted what was perhaps his life’s most personal and important statistical count. In June 1943, believing the Allied victory over Nazi Germany to be assured, Landau began to estimate the number of Polish Jews murdered in the Holocaust. He anticipated that by the war’s conclusion most of the surviving Jews in the Generalgouvernement would be ‘destroyed’ in one way or another.Footnote 71 Ultimately, Landau was also writing about his own end. Toward the close of 1943 blackmail attempts and death threats from local snatchers multiplied. On 29 February 1944 he was arrested on the streets of Warsaw and killed in unknown circumstances. The following day his wife and daughter were murdered.

As Landau was counting the dead in Nazi-occupied Poland, in London Central and Eastern European Jewish émigré economists were establishing what became a new social science discipline dedicated to planning industrialisation in the world’s poor regions. In June 1943 the Royal Institute for International Affairs published an article by Paul N. Rosenstein-Rodan, Problems of Industrialisation of Eastern and South-Eastern Europe, considered development economics’ foundational text.Footnote 72 A Polish Jew living in England, Rosenstein-Rodan knew Landau’s Warsaw circle and was influential enough to transmit to the Anglo-Saxon mainstream the Central and Eastern European structuralist approach to development. In 1947, on his way to Washington DC, Rosenstein-Rodan visited Warsaw to deliver a talk that Landau, had he survived, might have given. ‘Despite the assumptions of classic economic theory, capitalism did not level out the gap between the rich and the poor countries’, Rosenstein-Rodan lectured. Further, ‘poor countries should industrialise’ and ‘the growth of income between the rich and the poor countries of the world is extremely unbalanced’.Footnote 73

After the Second World War the idea that poor, agrarian countries should industrialise through state-led planning was elevated to the level of paradigm. The same was true in world-scale economics: the first United Nations economic report, Salient Features of the World Economic Situation from 1945 to 1947, covered ‘the entire world picture in broad terms’ because ‘in economic affairs neither single problems nor regions can be treated in isolation’.Footnote 74 The report’s author was Michał Kalecki, who, unlike his friend, survived the war and became the UN’s top economic expert. Landau’s impact on international developmental thinking becomes impossible to trace after this report. The global spread of development through industrialisation belongs to the history of Cold War politics and decolonisation that gave voice to the modern aspirations of Asian, and, later, African nations.

The significance of Landau’s work arises from the way he recognised and used the epistemic potential of eastern Europe – its liminal status – to change scholarly perceptions of the world. He claimed that Poland exemplified many problems of the global poor, but he also reached beyond the national case to create a statistical image of global inequalities, while pointing out the flaws in international statistics that had obscured such a view. The immediate focus of Landau’s work was certainly domestic: he wanted to prevent economic discrimination against ethnic minorities by generating expert knowledge to boost Poland’s economy by other means. However, World Economy’s intellectual relevance extends beyond Poland – and even Europe. Colin Clark, Landau’s British analogue, discussed the world’s national incomes without distinguishing between the coloniser and the colonised,Footnote 75 but Landau stressed precisely this distinction. Thus, in an effort as much methodological as political, he paved the way for the decolonisation of social science. Landau believed that each world region possessed an equal right to statistical visibility and, more importantly, to economic development and social welfare. His perspective opposed Eurocentrism, ‘an idea of seeing the world a resource to solve Europe’s problems’.Footnote 76 Landau did not end the Eurocentrism of modern social and human sciences, but he showed how it could be done.