Introduction

In many countries across the world, politicians provide material benefits in direct, contingent exchange for political support. A cross-national survey of 1,400 experts suggests that such patterns of “clientelism” exist in over 90 percent of countries, with “moderate” or “major” clientelist efforts in 74 percent of nations.Footnote 1 In twenty-six nations surveyed by the Latin American Public Opinion Project, nearly 12 percent of respondents “sometimes” or “always” received offers of handouts in exchange for their votes, a figure exceeding 16 percent in Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, and Paraguay.Footnote 2 Clientelism has important consequences for democratic accountability and responsiveness (Reference KitscheltKitschelt 2000), and is often understood to contribute to various maladies including the low provision of public goods, weak political institutions, and corruption (cf. Reference HickenHicken 2011, 302–304).

Many nations have pursued legislation against clientelism. Across the globe, 91 percent of countries ban vote buying during electoral campaigns.Footnote 3 But such attempts to curb the phenomenon frequently have limited success. For example, although Mexico’s electoral reforms have ratcheted up penalties against clientelism (e.g., in 1990 and 2014), their effectiveness is often “diluted in practice” (Reference SerraSerra 2016, 135–136). In Colombia, Eaton and Chambers-Ju (Reference Eaton, Chambers-Ju, Brun and Diamond2014, 108) find that several anti-clientelism reforms “unwittingly facilitated new forms of clientelism.” Elsewhere in the region, impunity with regard to clientelism has been observed in Guatemala and Panama (Carter Center 2003, 20, 46; Reference MannMann 2011, 5), and Peru’s Congress considered reforms in late 2017 that could even weaken legislation against vote buying.Footnote 4 Moreover, substantial challenges to anti-clientelism efforts extend well beyond Latin America (Reference Hicken and SchafferHicken 2007, 145).

Given these challenges, Brazil’s removal of so many politicians under a key anti-clientelism law presents an intriguing puzzle. Although the nation had long outlawed vote buying, politicians engaged in the practice with impunity as prosecutions were rare. After the introduction of Law 9840 in 1999, clientelism became the top reason why politicians are ousted, with over a thousand removals from 2000 to 2011.Footnote 5 The present article provides an extensive case study of this important new legislation and argues that both civil society and the judiciary played instrumental roles in its enactment and implementation. Beyond the remarkable number of politicians ousted, Law 9840 deserves investigation for additional reasons. As a cross-national study by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and Mexico’s electoral governance body emphasizes, Brazil’s anti-clientelism legislation “earns accolades” for its “innovative nature” (INE-UNDP 2014, 24–25). Furthermore, Law 9840 was the first law by popular initiative passed by the national legislature, originating from a petition signed by over a million Brazilians. As explored below, this feat required surmounting various obstacles: only four popular initiatives have been enacted by the national legislature over the past three decades.

The removal of so many politicians under Law 9840 may be particularly surprising, as the persistence of clientelism in Brazil has long captured scholarly attention (e.g., Reference LealLeal 1949; Reference HagopianHagopian 1996). Generations of researchers have investigated its role in Brazilian politics, including patron-client relationships between landowners and rural peasants during the colonial era, the role of powerful coroneis (colonels) during the oligarchic Old Republic (1889–1930), and the continued influence of cabos eleitorais (brokers). Law 9840 poses an important challenge for electoral clientelism, a phenomenon that by definition exclusively provides contingent benefits during campaigns. The literature suggests that politicians often engage in various forms of electoral clientelism, including vote buying and turnout buying (Reference NichterNichter 2008; Reference StokesStokes 2005; Reference Gans-Morse, Mazzuca and NichterGans-Morse, Mazzuca, and Nichter 2014). During my interviews in Northeast Brazil, numerous politicians suggested that Law 9840 influences behavior by substantially increasing candidates’ risk of punishment.Footnote 6 But it deserves emphasis that Law 9840 has by no means extinguished clientelism in Brazil. For example, Speck (Reference Speck2003) reports that 13.9 percent of survey respondents were offered cash or administrative favors for their votes in 2000, and nearly 10.7 percent of Brazilian respondents in the Latin American Public Opinion Project’s AmericasBarometer indicated that they were offered benefits for their votes during the 2014 campaign. Moreover, Law 9840 impinges less severely on contingent exchanges that extend beyond campaigns; both qualitative and survey evidence in Nichter (Reference Nichter2018) suggests that such “relational clientelism” also persists in many parts of Brazil.

While the present study focuses on anti-clientelism legislation, it builds on important research that emphasizes the key role civil society can play in fostering accountability (e.g., Reference FoxFox 2000; Reference O’Donnell, Peruzzotti and SmulovitzO’Donnell 2006). Even in contexts where elections offer limited vertical accountability, Peruzzotti and Smulovitz (Reference Peruzzotti and Smulovitz2006, 19–22) argue, civil society can promote “social accountability” by demanding new laws, pressuring for legal enforcement, monitoring officials’ behavior through “parallel ‘social watchdog’ organizations,” and other actions. In addition, civil society can prod “horizontal accountability agencies to assume their responsibilities” (Reference O’Donnell, Peruzzotti and SmulovitzO’Donnell 2006, 339), and it can provide a support structure that sustains judicial attention to rights or promotes their effectiveness (Reference EppEpp 1998; Reference Brinks, Botero, Brinks, Leiras and MainwaringBrinks and Botero 2010). Furthermore, recent studies emphasize that civil society can improve judicial impact through heightened compliance (e.g., Reference Langford, Rodríguez-Garavito and RossiLangford, Rodríguez-Garavito, and Rossi 2017; Reference BoteroBotero 2018). One important reason is that concerted action by allies may make it costlier to defy the judiciary’s rulings (Reference Brinks, Helmke and Rios-FigueroaBrinks 2011, 133–134). Building on such theoretical and empirical work, this article provides a case study about civil society’s role in partially mitigating a challenge to accountability, through Law 9840’s enactment and implementation.

Furthermore, this study provides additional insights about several factors deemed to improve the mobilization capacity of civil society. First, the extant literature often emphasizes the importance of enabling environments and political opportunities that reduce collective action costs (Reference AbersAbers 1998, 514; Reference TarrowTarrow 1998, 20). The present article examines one such environment: unlike prior years, post-authoritarian Brazil involved remarkably “extensive and regularized participation by civil society organizations” (Reference Friedman and HochstetlerFriedman and Hochstetler 2002, 37) and newly offered the opportunity to present popular initiatives. Second, the literature frequently underscores how external agents may provide crucial resources and capabilities that help mobilize civil society; for example, the Catholic Church, which played a key role in mobilizing a broad network of NGOs in support of Law 9840, is understood to have often “played a critical role in helping popular organizations get off the ground” in Latin America (Reference AbersAbers 1998, 514). Such regional organizations often foster collective action by overcoming divides between disparate communities and can heighten access to information needed to monitor precise areas of impunity (Reference FoxFox 1996, 1091–1096; Reference FoxFox 2000, 15). Third, evidence from other continents suggests that civil society organizations may be more successful in mobilizing against corruption when they develop alliances with state institutions (Reference AderonmuAderonmu 2011, 82–83; Reference JenkinsJenkins 2007, 59, 65), as they did with Law 9840 in Brazil. Overall, this study illustrates how such factors shaped the trajectory of this impressive legislation.

While evidence suggests that many politicians have been prosecuted under Law 9840, claims about its responsibility for a broader decline in impunity must be tempered. Various socioeconomic and institutional factors may have also played an important role. For instance, incomes have risen substantially in recent decades (Reference Ferreira, Messina, Rigolini, López-Calva, Lugo and VakisFerreira et al. 2013, 101), which may lead citizens to become less amenable to clientelism and more likely to report transgressors. In addition, further research is needed to understand how well lessons from Brazil might travel to other countries with clientelism, especially in contexts with weak civil society and judicial autonomy. Despite such limitations, this article yields intriguing insights about the role of civil society and the judiciary in Brazil’s fight against clientelism.

Impunity before Law 9840

Brazilian laws long prohibited clientelism during campaigns but were rarely enforced. When Getúlio Vargas codified electoral rules after the Revolution of 1930, candidates were banned from distributing campaign handouts in exchange for political support. The first Electoral Code in 1932 imposed a significant punishment for the practice: imprisonment of six months to two years. An even more substantial punishment was established by the most recent Electoral Code of 1965: imprisonment of up to four years, as well as fines. These laws not only proscribed vote buying but also banned a wide range of actions including turnout buying and abstention buying, even if politicians merely promised benefits or if their offers were refused. For example, the 1965 Electoral Code renders it a violation of criminal law “to give, offer, promise, solicit or receive, for oneself or for another, money, gifts, or any other benefits, in order to obtain or give a vote, or to obtain or promote abstention, even if the offer is not accepted.”

Even though such laws criminalized clientelism, they were almost entirely unenforced (Câmara dos Deputados 1999; CBJP 2000). Until the introduction of Law 9840, it was rare for politicians to be charged with clientelism, and even fewer were prosecuted successfully.Footnote 7 As emphasized by the Brazilian Senate in a press release commemorating Law 9840’s tenth anniversary: “Formerly, vote buying, although condemned by the Electoral Code, was rarely punished.” Likewise, the Public Prosecutor’s Office (Ministério Público Federal) indicated that vote buying was “almost never punished” before Law 9840—“giving offenders the absolute certainty of impunity”—and the former chief justice of the Superior Electoral Court (Tribunal Superior Eleitoral, or TSE) underscored that until Law 9840 procedural requirements had “precluded punishment” for vote-buying infractions. Moreover, a prominent newspaper emphasized that “effective punishment” against vote buying “was only possible thanks to” Law 9840, quoting a leader of Brazil’s Bar Association (Ordem dos Advogados do Brasil, or OAB): “Today we have the efficacy of the Electoral Judiciary. Before it was a joke, there was no fight against electoral corruption, the legal instruments were completely ineffective.”Footnote 8 Delays and backlogs in the legal system, which faces substantial inefficiencies due to procedural problems and resource constraints (CNJ 2010), hindered punishment (Câmara dos Deputados 1999). As one of Brazil’s most prominent judges commented about vote buying before Law 9840: “the famous slowness of the judiciary … facilitated impunity” (Reference DelgadoDelgado 2010).

If convicting politicians for clientelism was tough, their ouster was even more challenging. Those convicted would file many appeals, enabling them to complete their terms in office (Reference ReisReis 2006, 17). The nation had long presumed that defendants were innocent until proven guilty and until all appeals were exhausted.Footnote 9 This extended presumption of innocence, which is enshrined in the 1988 Constitution and motivated in part by human rights violations of the former military dictatorship, guarantees defendants many opportunities to appeal.Footnote 10 An unintended consequence is that even the most obviously guilty defendants can remain free for many years by filing frivolous appeals. With respect to clientelism, such lengthy appeals delayed removals of those rare politicians who were actually convicted. This reality, combined with the paucity of prosecutions, meant that many Brazilian politicians engaged in clientelism with impunity. During Law 9840’s deliberations in 1999, a federal deputy even contended that of all “criminalized behavior” in the nation, vote buying was “one of the most practiced with almost no punishment”—a problem he blamed on delays in criminal prosecution.Footnote 11

As explored next, Law 9840 introduced new sanctions. During my interviews on clientelism, numerous local politicians emphasized its importance. For example, one councilor claimed that whereas “before the electoral law clearly wasn’t very rigid” with regard to vote buying, Law 9840 gave a “new face to Brazilian politics”—now the “TSE doesn’t allow it!” Another city councilor similarly pointed to a “great change triggered by” the “electoral legislation that prohibits vote buying.”Footnote 12

Prosecutions after Law 9840

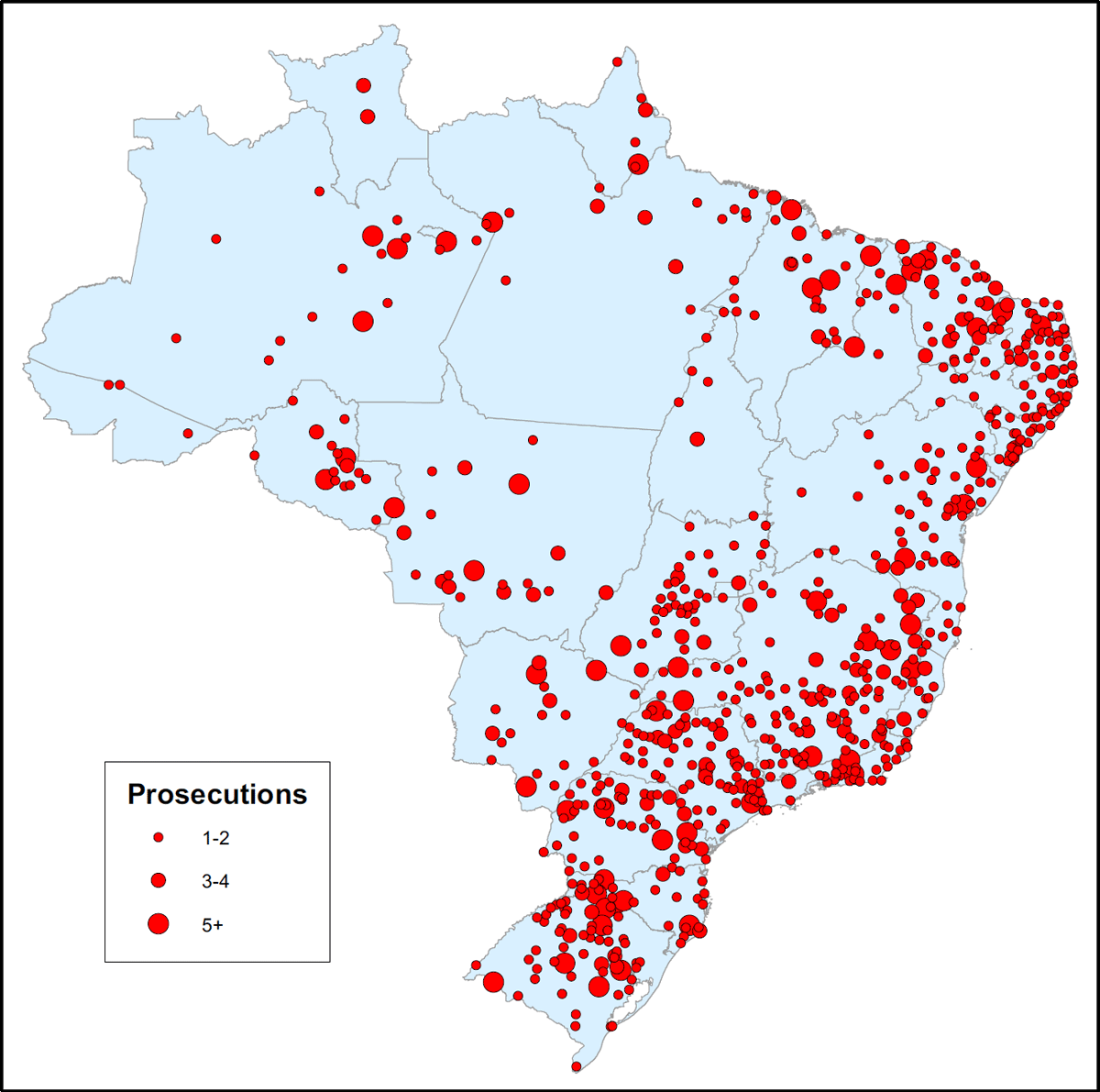

The masterstroke of the new legislation against clientelism during elections (Law 9840) was to classify the practice as an electoral infraction. This step expedited the judicial process and allowed for the immediate removal of guilty politicians. Essentially, the law created an administrative sanction that could be pursued entirely separately from—and more expeditiously than—any criminal charges for clientelism (Reference ReisReis 2006, 43; Reference TozziTozzi 2008). While Law 9840 is typically used to combat vote buying, court rulings show that it also prohibits other types of electoral clientelism (Reference PradoPrado 2014, 55–56).Footnote 13 To motivate a more thorough discussion, I first present evidence that many politicians were ousted by Law 9840. Movimento de Combate à Corrupção Eleitoral, an umbrella network of civil society organizations against clientelism, identified almost seven hundred politicians removed by 2009 (MCCE 2009). Furthermore, various publications spanning government, media, and civil society estimate that over a thousand politicians have now been removed for vote buying through Law 9840.Footnote 14 These removals occurred throughout Brazil, as shown in Figure 1. This figure demonstrates the extent to which politician removals are geographically distributed but does not control for municipal characteristics such as electorate size or population density. Nevertheless, this geographical distribution does not merely mirror such factors. For example, nearly 44 percent of removals were in the poorer North and Northeast regions—where 33 percent of voters live—and almost 71 percent of removals occurred in districts with below-median population density.Footnote 15 Further details about regional characteristics and Law 9840 are provided in Table 1; data on signatures and committees are discussed below. Municipal politicians account for the vast majority of prosecutions. Whereas 667 mayors, vice mayors, and city councilors were removed from candidacy or office during local elections (in 2000, 2004, and 2008), only 31 state and federal politicians were removed (in 2002 and 2006). One reason is just that municipal candidates are by far the most numerous in Brazil. Another reason, emphasized by many citizens and politicians I interviewed in the Northeast region, is that clientelism is far more prevalent during local elections. Among ousted local politicians, over two-thirds are mayors and vice mayors (who are removed jointly), while a third are city councilors (MCCE 2009). It should be noted that these data do not distinguish between removals during politicians’ candidacies versus after their election, a distinction that warrants greater attention in future research.

Figure 1: Politician removals for clientelism during elections (2000–2008). Author’s analysis of data from MCCE. Dots reflect location of first-instance electoral courts issuing at least one verdict to oust a politician (elected or running for office) for violating Law 9840 in municipal elections in 2000–2008. Size of dots represents the number of politicians for whom removal verdicts were issued.

Table 1: Politician removals, signatures, and committees (Law 9840).

Sources: MCCE (2009, 2013); Câmara dos Deputados (1999); Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada, http://www.ipeadata.gov.br/; Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, Censo Demográfico 2010.

Note: Regional breakdowns exclude eleven politicians and 1,797 signatures with unspecified locations. GDP/capita uses exchange rate on December 30, 2000, from Banco Central do Brasil.

Court proceedings from Law 9840 prosecutions show that clientelism involves a broad range of handouts, including food, clothing, building supplies, cash, and other goods. For illustrative purposes, consider two examples involving healthcare from court documents. Electoral authorities raided a mayor’s house in Paraíba during the 2004 campaign and discovered sacks of pills that were proven to be distributed in exchange for votes; he and his vice mayor were ousted. In another municipality, a councilor was removed from office for buying votes using dentures as payoffs: he distributed signed vouchers for dental prostheses, which numerous citizens redeemed in exchange for their votes.

The prevalence of such removals for clientelism during elections is increasing. Figures from local elections demonstrate an upward trend: 95 removals of politicians elected in 2000, 215 removals of politicians elected in 2004, and 357 removals of politicians elected in 2008 (MCCE 2009).Footnote 16 For the first few months after the 2008 election, a mayor was ousted for clientelism every sixteen hours.Footnote 17 Moreover, these figures include only guilty verdicts after any appeals; far more politicians faced Law 9840 charges. For instance, Barboza (Reference Barboza2015, 83–84) finds that less than a quarter of all politicians charged with vote buying in São Paulo State in 2012 were found guilty, and over half of those verdicts were overturned on appeal. An analysis by the TSE revealed that of four thousand legal proceedings to oust local politicians during the 2008 elections, about three thousand mentioned “vote buying.”Footnote 18

As a direct consequence of all these removals, Law 9840 contributes to a “parallel electoral calendar.”Footnote 19 When mayors are removed from office for clientelism, municipalities often hold new elections. Between January 2009 and June 2012, 163 municipalities held new mayoral elections, many due to clientelism removals.Footnote 20 The Northeast region had the highest number of new elections during this period (seventy-one elections), and in the state of Piauí, the rate reached one new election per nine municipalities. Brazil’s rate of new mayoral elections after the 2008 election was five times greater than after the 2004 election, and reached a record high in 2013.Footnote 21 In some cases, politicians who are found guilty of clientelism receive injunctions to remain in office pending an appeal, but these are exceptions to the rule.Footnote 22 The overall point is that whereas clientelism during elections was rarely punished before Law 9840, many politicians were ousted for the practice after this legislation.

Enactment of Law 9840

Popular initiatives in Brazil

The enactment of Law 9840 was facilitated by an important feature of the enabling environment: the ability to introduce legislation by popular initiative. Channels by which the public could influence legislation were absent during much of Brazil’s political history, and the country embraced popular participation when it developed a new constitution after its 1985 return to democracy. The 1988 Constitution established popular initiatives as a way to put forth bills for voting by the legislature: they require signatures from at least 1 percent of the national electorate, including at least 0.3 percent of the voters in each of five states.

Despite offering an institutionalized channel for popular pressure, only four popular initiatives have been enacted by Brazil’s national legislature over the past three decades, in large part due to four key obstacles.Footnote 23 First, the Constitution established initiatives but lacked crucial procedural details; these rules were only codified a decade later (Law 9079 in 1998), hindering initiatives. Second, the large number of voter signatures required—over 1.0 million in 1998 and nearly 1.5 million in 2018—presents a massive challenge. Several attempts failed for this reason and an amendment was even proposed to halve the required number of signatures (Reference ReisReis 2006, 68). One legislator emphasized, “it’s not easy to drum up a million signatures to present a bill!”Footnote 24 Another argued, “the requirement level to submit a proposal at present is very large, which discourages participation” (Reference Assunção and AssunçãoAssunção and Assunção 2014, 157). Third, their success hinges on the involvement of organizations that can mobilize voters on a national scale, as many signatures are required from at least five states (Reference Assunção and AssunçãoAssunção and Assunção 2014, 157). These organizations may also need to be reputable, as some citizens are fearful of signing initiatives that may be opposed by powerful politicians (Reference Assunção and AssunçãoAssunção and Assunção 2014, 157). And fourth, even after signatures are collected, enactment is uncertain. Congress has not yet established a way to verify so many signatures; as a workaround, all successful popular initiatives have been “adopted” by supportive politicians. Furthermore, alliances with elites help to ensure that initiatives are neither stalled nor diluted upon reaching the legislature. While Law 9840 was the first popular initiative to be approved by the national legislature, another initiative reached the legislature earlier but took thirteen years to be approved and was “completely disfigured” (Reference Assunção and AssunçãoAssunção and Assunção 2014, 159). Given these four key obstacles, the successful enactment of Law 9840 is particularly impressive and warrants examination. The next two sections examine how civil society and the judiciary helped overcome these obstacles facing popular initiatives, thereby facilitating the enactment of Law 9840.

Role of civil society

Civil society played a crucial role in enacting the anti-clientelism legislation. Over sixty nongovernmental organizations collaborated on an eighteen-month campaign to gather signatures. Obtaining over one million signatures required substantial efforts, which were orchestrated by Brazil’s Justice and Peace Commission (Comissão de Justiça e Paz, or CBJP). This religious entity extends a worldwide Vatican effort to foster social justice and poverty reduction. The involvement of this commission, and the Catholic Church more generally, in anti-clientelism efforts builds on decades of social and political advocacy. During the authoritarian period, the commission played a central role in the Catholic Church’s campaign against human rights abuses (Reference MainwaringMainwaring 1986, 106–107), and provided various forms of support “to virtually all the campaigns and movements for the redemocratization of Brazil” (Reference PopePope 1985, 439). While striving to remain politically neutral, both the commission and the Church aimed to heighten citizens’ political awareness and freedom of choice (Reference PopePope 1985, 447). The anti-clientelism campaign dovetailed with these broader efforts. Given the third obstacle to popular initiatives discussed above, the territorial reach and visibility of the Catholic Church in Brazil deserves emphasis: it has the most dioceses (and Catholics) of any country in the world.

As one of its periodic campaigns against problems facing Brazil, the Justice and Peace Commission initiated a working group against vote buying in 1997 (CBJP 2000, 63). It conducted a nonscientific survey of 226 parishes across twenty-one states, which according to the group’s leader “reinforced the need for immediate and efficient action”: 96 percent of parishes indicated that at least some mayoral candidates “did favors for voters” during the 1996 election campaign.Footnote 25 The commission concluded that the judicial system’s inefficiency was a central reason politicians remained unpunished for clientelism and a popular initiative could promote meaningful change (CBJP 2000, 64). The commission soon presented its findings to the general assembly of its influential sister organization, the Conferência Nacional dos Bispos do Brasil (National Conference of Brazilian Bishops, or CNBB), which has been historically described as “the ultimate authority of the Catholic Church in Brazil” (Reference MainwaringMainwaring 1986, 84).Footnote 26 The two organizations jointly conducted further research and held public discussions about clientelism across Brazil over the next year (Câmara dos Deputados 1999). Lessons from these efforts informed the work of a task force that drafted the initiative (discussed below).

After drafting the popular initiative, the Justice and Peace Commission and CNBB began to collect signatures in May 1998, with over sixty civil society organizations lending support (CBJP 2000, 65–66). Over 40 percent of these organizations were religious organizations, of which at least three-fourths were closely linked to the CNBB.Footnote 27 Such broad collaboration builds on past activism under military rule, which enabled a “dense web of interlocking religious and secular civic organizations” with considerable “cross-fertilization” in terms of membership and even leadership (Reference HagopianHagopian 2008, 157). During the popular initiative, the organizations engaged in a wide range of activities, including grassroots campaigning, holding collective news conferences, and issuing newsletters. Efforts especially ramped up during the 1998 national election campaign, employing a widely publicized slogan still used today: “A vote doesn’t have a price, it has consequences” (CBJP 2000, 67). By mid-August 1999, the campaign gathered the required signatures, and representatives from over thirty organizations delivered truckloads of signature pages to the national congress.

Although civil society organizations gathered signatures in all states, collection was uneven across Brazil. Four states in the wealthier South and Southeast regions with only 41 percent of the national electorate—São Paulo, Minas Gerais, Paraná, and Espírito Santo—accounted for 69 percent of signatures.Footnote 28 Over twice as many residents of São Paulo signed the petition as in any other state: with 393,259 signatures, this state with 22 percent of Brazil’s electorate accounted for 38 percent of signatures. And by contrast, only 17 percent of signatures were collected in the poorer North and Northeast regions, where 33 percent of voters reside (see also Table 1). One plausible reason is that citizens with higher incomes may be relatively more averse to clientelism and thus more inclined to sign an anti-clientelism petition. But this explanation is partial at best, as some relative wealthy states such as Rio de Janeiro also had disproportionately low signatures.Footnote 29 A leader of Brazil’s anti-clientelism movement suggested that signatures might have been geographically concentrated in part due to variation in the institutional capacity of participating civil society organizations.Footnote 30 This explanation clarifies one reason why São Paulo may have so many signatures: its branch of the Justice and Peace Commission had long played a prominent role in popular mobilization (e.g., Reference ReisReis 2013, 65–66), especially under its influential former archbishop Dom Paulo Evaristo Arns (Reference PopePope 1985, 430). The commission’s national leader during the enactment of Law 9840, who actively participated in its São Paulo branch, had also served eight years as a São Paulo city councilor (1988–1996) just before the initiative commenced. Moreover, nearly a third of the other civil society organizations involved in the popular initiative were headquartered in São Paulo,Footnote 31 and three of eight public meetings held to obtain input about the proposed legislation were in the state. Thus, the uneven collection of signatures across Brazil is likely due to the institutional capacity of civil society organizations, as well as other factors such as heterogeneity in citizen preferences.

To sum up, civil society played an integral role in spearheading the anti-clientelism initiative. The efforts of sixty civil society organizations, led by two closely associated religious organizations (the Justice and Peace Commission and CNBB), facilitated the collection of over one million signatures. Indicative of this fundamental role is Law 9840’s nickname, Lei dos Bispos, or “Bishops’ Law.” This nickname was used during congressional deliberations about the popular initiative and remains in use today.

Role of the judiciary

The judiciary also collaborated with civil society organizations to help enact the new legislation. Before I examine these actions, the role of the judiciary in Brazilian elections deserves emphasis. Unlike in many other countries, electoral governance in Brazil—including activities such as registering voters, applying rules, certifying results, and processing lawsuits—is highly centralized in the judicial branch of government (Reference MarchettiMarchetti 2008, 882–883). Its integration with the judiciary is so substantial that the electoral management body is even called the “Electoral Judiciary” (Justiça Eleitoral). Other branches of government have a relatively minor role in electoral governance; for example, Brazil is only one of four countries in Latin America in which the legislature plays no role in choosing leaders of the electoral management body (Reference MarchettiMarchetti 2008, 878). This integration has enabled the TSE to rule on electoral matters with a substantial level of autonomy. In addition, most observers view the TSE to be relatively well insulated from political influence. Various metrics, including the appointment and tenure of justices, also suggest the overall independence of electoral governance in Brazil (Reference Hartlyn, McCoy and MustilloHartlyn, McCoy, and Mustillo 2008). Lower-level judges in the overall legal system, who also form the corps of first-instance electoral judges, are selected by rigorous competitive examination.

The role of the judiciary in electoral governance made this branch of government a valuable ally for civil society in the fight against clientelism. Civil society groups recruited the active participation of influential members of the judiciary in the popular initiative. In early 1998, when the Justice and Peace Commission formed a task force to draft the initiative, it brought in current and former leaders of the judiciary from across the country. Such cooperation has long-standing precedent; for instance, when the commission’s influential São Paulo branch was launched in 1972, Church leadership appointed lawyers, legal scholars, and former prosecutors to six of its nine board membership positions, a gambit providing both legitimacy and expertise in the organization’s fight against human rights abuses (Reference PopePope 1985, 433–434).Footnote 32 This entity continued such collaboration in the 1980s, as it joined members of Brazil’s Bar Association (OAB) to collect citizen signatures for the purpose of fostering popular participation in the 1988 Constituent Assembly (Reference ReisReis 2013, 65–66). The 1998 anti-clientelism task force was led by a recent attorney general of Brazil, with other members including a regional public prosecutor from Ceará and a former electoral judge from São Paulo (Câmara dos Deputados 1999). These and other members’ substantial judicial experience enabled them to find a way to circumvent the legal quagmire that had long faced clientelism prosecutions. Cognizant of the many convoluted obstacles facing criminal proceedings, the task force opted to establish a civil law against campaign handouts. The sanctions imposed through Law 9840—removal from office and fines—would not substitute for criminal charges. Instead, these penalties would be levied through a parallel, expedited process. In short, while clientelism during elections continued to be a crime, it also became a punishable electoral infraction. Building on this idea, the current and former members of the judiciary carefully drafted the popular initiative.

Several features likely contributed to the judiciary’s role in Law 9840. First, an important contingent of judges wanted to combat vote buying, as shown by their involvement in the law’s enactment. One motivation may be the “new form of judicial activism” that Taylor (Reference Taylor2005, 425) observes after the 1988 Constitution, which emphasized social justice and instilled an “ethos of protecting the vulnerable” within the judiciary. Second, the judiciary had substantial autonomy. Brazil’s high level of political fragmentation contributes to this autonomy, in part by making it more challenging for politicians to punish judges (Reference Brinks, Helmke and Rios-FigueroaBrinks 2011, 130, 139). Moreover, Taylor (Reference Taylor2005, 423) explains that various aspects of the 1988 Constitution heightened judicial independence, including its guarantee of judges’ merit-based recruitment and tenure until age seventy, as well as courts’ autonomy on administrative and financial matters. Third, a new generation of judges had enhanced training. For instance, the 1988 Constitution required special judicial schools (Reference DakoliasDakolias 1995, 220–221), and judges increasingly had judicial training at the start of their careers: 40 percent of judges entering their position by 1990, 58 percent of those entering from 1991–2000, and 77 percent of those entering from 2001–2010 (CNJ 2018, 27).

Early involvement of the judiciary not only yielded a clever workaround to a Byzantine criminal process but also improved the technical accuracy of the popular initiative. In turn, this technical accuracy helped prevent the initiative from becoming bogged down by procedural issues upon reaching the legislature. The initiative quickly received approval of the constitutional committees of both chambers of Congress. For example, it was unanimously approved after just two hours of debate by the constitutional committee of the Chamber of Deputies (CBJP 2000, 75). The early involvement of senior members of the judiciary helped propel the project toward approval by both houses in just thirty-five days, one of the fastest deliberations in the history of Congress (Câmara dos Deputados 1999). By comparison, a more recent popular initiative took approximately eight months to be approved by both houses, a pace that was “considered rapid.”Footnote 33 Of course, other reasons contributed to this quick turnaround, including the extent of popular pressure and an impending deadline for the law to take effect by the 2000 elections.

In addition to offering valuable expertise, the judiciary also provided direct public support on behalf of the anti-clientelism campaign. Particularly valuable were public words of support provided by the TSE president (i.e., the head of the electoral governance body). This support was prompted by a request from the Justice and Peace Commission and Brazil’s Bar Association, and helped to generate signatures and give additional legitimacy to the campaign (CBJP 2000, 67). Other members of the judiciary also supported the campaign, though most not publicly. As Judge Márlon Reis, who later became a leader of the MCCE, explained: “I was rooting for the law to pass, because as an electoral judge who lived in a very small city in the interior of Maranhão, I witnessed these practices of clientelism and vote buying, and I imagined this could be an excellent idea to improve our democracy.”Footnote 34 Overall, efforts by the judiciary contributed to the anti-clientelism campaign, which was spearheaded by civil society organizations.

In sum, actors from civil society and the judiciary advocated on behalf of the anti-clientelism initiative.Footnote 35 Legislation emerging from the popular initiative was signed by President Fernando Henrique Cardoso, culminating in Law 9840’s formal enactment on September 28, 1999. But enactment was only part of the battle. I now turn to factors contributing to the successful implementation of the law, which has already prosecuted over a thousand politicians.

Implementation of Law 9840

The enactment of Law 9840 provided a valuable new tool to prosecute politicians for distributing campaign handouts. Instead of relying only on criminal charges that involve years of court proceedings, judges could now also immediately oust politicians for committing an electoral infraction. But various rules previously written into parchment had little impact on clientelism. As documented above, politicians were rarely charged with clientelism before Law 9840, and even fewer were prosecuted successfully. To investigate the puzzle of how so many politicians were ousted under the new law, this section examines the central role of civil society and the judiciary in its implementation.

Role of civil society

Civil society contributed substantially to Law 9840’s implementation. Given that civil society had been activated during the law’s enactment, there already existed a broad network of nongovernmental organizations mobilized to work toward its successful implementation. In fact, the Movimento de Combate à Corrupção Eleitoral—an ongoing umbrella network of civil society organizations against clientelism that coordinates the “9840 Committees” discussed below—has origins in the mobilization for the popular initiative that culminated in Law 9840.Footnote 36 Soon after the law’s passage, the Justice and Peace Commission and other organizations issued a report expressing concern it would be ineffective without civil society’s diligence (CBJP 2000). Particularly crucial tasks were gathering evidence against politicians and vigilant monitoring of local electoral courts to ensure they prosecuted violators. To this end, the commission published an extensive guidebook calling for communities to create “9840 Committees.” These committees soon mushroomed across Brazil, with 130 operating in 17 states by the 2002 national election, involving the participation of 1,600 citizens. By 2013, 329 committees operated in every state across the country.Footnote 37 As Table 1 shows, these committees were formed disproportionately in poorer regions, unlike the initiative’s concentration of signatures in wealthier regions. More than 44 percent are located in the poorer North and Northeast regions, where 33 percent of voters live. By contrast, 47 percent of committees are located in the wealthier South and Southeast regions, where 60 percent of the electorate resides.Footnote 38

To glean insight about civil society’s role in implementing Law 9840, consider a report issued by a committee in Natal after the 2000 election (Comitê 9840 2000).Footnote 39 Members of an existing NGO learned about the new law and decided to form a 9840 Committee about three months before the election. Given the religious origins of Law 9840, they first sought the blessing of the nearest archbishop, who offered the support of the local church. The founders held a planning meeting, joined by members of the archdiocese, Brazil’s Bar Association (OAB), the Public Prosecutor’s Office (Ministério Público), unions, and the press. Over the next few months, the 9840 Committee conducted presentations, public discussions, and press interviews. They formed a clientelism hotline at the OAB offices, receiving over two hundred calls—half on election day, and many providing details about where politicians were buying votes. The committee indicated only some calls were investigated, partially due to insufficient assistance from authorities. A local newspaper reported the 9840 Committee was “a promising seed in the area of true citizenship … organized society can apply pressure so that laws are obeyed.”

A survey by Melchiori (Reference Melchiori2011, 73–75) provides additional information about 9840 Committees, though only 47 of Brazil’s 306 committees in 2011 participated and respondents may not be representative.Footnote 40 About 53 percent of surveyed committees had fifteen or fewer members, 26 percent had between sixteen and thirty members, 9 percent had between thirty-one and fifty members, and 13 percent had over fifty members. Among their membership, over half of committees had a lawyer, and nearly one-fifth had a judge or prosecutor. Nearly two-thirds of committees held regular meetings, but only half had a headquarters or fixed location. With respect to activities, 79 percent worked on Law 9840 enforcement, 79 percent conducted awareness campaigns, and 68 percent held panels and seminars. In recent years, many 9840 Committees have expanded their scope of activities beyond clientelism. For example, in Maranhão a 9840 Committee partnered with two government organizations (Controladoria-Geral da União and Tribunal de Contas da União) to train voters how to monitor public expenditures.

In short, evidence about 9840 Committees points to the important role of civil society in implementing the new legislation, building on its earlier activation during the popular initiative. As Judge Márlon Reis explains, with Law 9840 “there wasn’t only the introduction of a new electoral rule. More than this, the decisive factor for applying the law was social mobilization behind it.”Footnote 41 This mobilization heightens citizens’ participation, which is often credited with increasing clientelism prosecutions. As explained by the president of an OAB anti-clientelism commission: “The population started to make more accusations. With more accusations, there are more legal proceedings, more judgments, and more removals.”Footnote 42

Role of the judiciary

The judiciary also plays a decisive role in implementing Law 9840. When drafting any law, it is difficult to stipulate every possible contingency, so judicial interpretation is crucial. If electoral courts had wanted to water down the effects of Law 9840, they could have narrowly interpreted the law to restrict politicians’ removal. But courts have done the opposite. The law was deemed an excellent tool for achieving the judiciary’s mandate of holding free and fair elections. As Reis (Reference Reis2006, 49) explains: “Until the advent of Law 9840 … the Electoral Judiciary was responsible for a mission that it couldn’t achieve.” To make use of this new tool, electoral courts interpreted Law 9840 in a manner that heightened punishments against clientelism. Indeed, the TSE—Brazil’s top electoral court—emphasized in a press release that it “started to significantly modify its jurisprudence” after its enactment to “guarantee the effectiveness of Law 9840.”Footnote 43

To motivate discussion of specific TSE actions that facilitated Law 9840’s implementation, consider the surge in court activity pertaining to the legislation since its enactment. I measure this activity using a text search of more than 320,000 court documents from 2000 to 2013—the entire contents of all electoral court judgments and resolutions during that period at the federal and state level in the TSE’s searchable system. The search term is the actual terminology employed in Law 9840 for the proscribed act: “captação ilícita de sufrágio” (illicit capture of suffrage). While frequently translated in the press as “vote buying,” the phrase also pertains to other forms of electoral clientelism including abstention buying (Reference ReisReis 2006, 59–60; Reference PradoPrado 2014, 55–56). Between 2000 and 2013, 6,557 documents contain this term, representing 2.0 percent of all documents. Figure 2 shows that the share and number of documents referring to “captação ilícita de sufrágio” has grown significantly since 2000, surpassing 5.8 percent of documents in 2013. Observe its particularly high prevalence after the municipal elections held in October 2004, 2008, and 2012, when clientelism is considered most pervasive and the greatest number of candidates run for office. A few points should be noted. First, no documents in the electoral court database referred to “captação ilícita de sufrágio” prior to the enactment of Law 9840 in 1999; vote buying was not yet classified as an electoral infraction, so the electoral courts did not oust politicians for the practice. Instead, it had exclusively been punishable by criminal law. Second, few court documents are observed until several years after Law 9840’s enactment, partly due to reasons discussed below. Third, the timing of these documents lags their first adjudication, as they are from state and federal electoral courts, which are appellate courts for municipal politicians.

Figure 2: Electoral court documents mentioning clientelism (2000–2013). Author’s analysis of data from Tribunal Superior Eleitoral. Vertical axes represent the number and percent of electoral court documents in each year mentioning “captação ilícita de sufrágio” (illicit capture of suffrage), the term used for clientelism in Law 9840.

The judiciary has issued various rulings enhancing Law 9840’s implementation. Soon after its enactment, lawyers representing ousted politicians argued that the removal of politicians created a new ineligibility criterion for candidates and thus required a constitutional amendment (Reference ReisReis 2006, 45–47). The TSE quickly ruled Law 9840 constitutional, because it merely creates an administrative penalty for an electoral infraction (Reference SanseverinoSanseverino 2008, 205). As another example, the TSE ruled that Law 9840 prohibits campaign handouts regardless whether the election outcome is changed (Reference MedinaMedina 2004, 113). As TSE justice José Delgado explains, “If the purchase of one vote is proven, this is already a reason for removal.”Footnote 44 This interpretation stems from the landmark “Caixa d’água” case, in which a mayoral candidate gave a water tank to a voter. Upon winning the election, he took back the tank because he suspected that the citizen hadn’t voted for him. The TSE removed the mayor, despite having evidence of only a single transaction with no impact on the election.Footnote 45 Such judgments heighten the law’s effectiveness and increase politician removals.

The judiciary also strengthened Law 9840’s implementation through rulings about indirect transactions and the scope of proscribed activities. Politicians often employ campaign workers and brokers to distribute handouts. Although the submitted draft of the popular initiative included a clause specifically prohibiting such indirect transactions, legislators argued vehemently to remove it.Footnote 46 Law 9840 includes no mention of indirect transactions, which initially limited its effectiveness (Reference da Costada Costa 2009, 212). TSE jurisprudence eventually evolved to include indirect transactions (Reference ReisReis 2006, 57); handouts can now result in a politician’s ouster if she was aware of the activity and did not stop it (Reference SanseverinoSanseverino 2008, 209). Another problematic clause in Law 9840—inserted by legislators—permitted “campaign gifts” such as partisan T-shirts (CBJP 2000, 19–21). Some observers believed politicians could still buy votes with such handouts (Reference ReisReis 2006, 29). For example, Senator Heloisa Helena expressed concern politicians could emblazon slogans on various clientelist handouts and call them “campaign gifts.”Footnote 47 The TSE ended such ambiguity when it passed legislation in 2006 broadening the scope of banned items; for example, to include T-shirts, key chains, hats, pens, and food boxes (Reference SanseverinoSanseverino 2008, 207).

The judiciary has also increased clientelism removals by deeming acceptable a wide range of evidence. Politicians do not need to be caught red-handed by authorities. For example, as long as citizens involved in exchanges consent, video or audio recordings of transactions are sufficient (MCCE 2006, 32). But only a minority of cases involve such evidence. Eyewitness testimony is the most common form of evidence in Law 9840 cases and is often sufficient for prosecution (MCCE 2006, 32). Although TSE jurisprudence indicates a single witness alone is insufficient, in one case a witness’s account accompanied with handwriting analysis yielded a guilty verdict (Reference CureauCureau 2010). Circumstantial evidence alone can also be used to oust politicians for Law 9840 violations. For example, a prosecution in Rio de Janeiro was based on large sums of cash in small denominations, and a list of names with voter identification numbers, in a campaign office (Reference CureauCureau 2010). This breadth of permissible evidence heightens politician removals.

The judiciary also fosters Law 9840’s implementation by permitting politicians’ immediate ouster. This issue continues to be contentious among both courts and legal scholars, but TSE jurisprudence has evolved to rule definitively that Law 9840 penalties should be executed immediately (Reference ReisReis 2006, 81–84). That is, politicians should be ousted immediately after guilty verdicts are imposed by lower-level courts. Because Law 9840 removes politicians through an administrative sanction, the quagmire of lengthy procedures and appeals through the criminal courts is circumvented. Because elections are time sensitive, the Electoral Code more generally indicates that rulings during campaigns should take effect immediately (Reference ReisReis 2006, 81). The overall process for a 9840 prosecution takes approximately three weeks, with specified times permitted for each stage of the process (Reference TozziTozzi 2008, 41–42). The appeals process is also fast; for example, second-instance courts have only three days to rule whether an appeal warrants a hearing (Reference CureauCureau 2010). Some provisions ensure due process during appeals. If the election has not yet been held, the candidate can continue to advertise and have his or her name on the ballot until the appeal is heard (Reference TozziTozzi 2008, 50–51). Elected politicians are removed from office during appeals, unless appellate courts issue injunctions to prevent what they consider irreparable harm (Reference CureauCureau 2010).

The judiciary must exercise caution lest Law 9840 be manipulated as a tool to harm competitors. For example, after investigating a submitted video claiming to show vote buying, an electoral judge in Mato Grosso State decried a “Machiavellian plan” by the opposition to frame a mayoral candidate.Footnote 48 And in one case, a mayor in Paraná—who ended up being impeached for fraudulent public contracts—was under investigation for allegedly paying residents to claim they had been received vote-buying payments from a competitor.Footnote 49 To avoid such manipulation, a chief prosecutor explains, it is necessary to “be careful, we must thoroughly investigate to be sure it’s not a case of buying a witness to reverse the result of a legitimate election.”Footnote 50 The appeals process is designed to safeguard against potential manipulation. In fact, the president of Brazil’s Bar Association complained that there are too many opportunities for appeals, which allows mayors to serve in office after judgments.Footnote 51

Beyond the broad array of favorable jurisprudence discussed above, the TSE continues to conduct various public anti-clientelism campaigns. For example, it issues many public service announcements on both radio and television stations. One television advertisement shows political operatives carrying away a voter in a box after buying his vote, with the following voiceover: “Don’t transform your opinion into merchandise. Don’t sell yourself. Vote buying is a crime.”Footnote 52 Another advertisement features a pregnant woman patting her stomach, asking viewers not to sell their votes in the interest of both present and future generations.Footnote 53 Furthermore, in honor of the ten-year anniversary of Law 9840, the TSE issued an educational video, a documentary, and held a widely publicized conference.Footnote 54 Such TSE efforts, in addition to civil society actions, have apparently borne fruit: 72 percent of respondents in a 2008 survey reported familiarity with the anti-clientelism law.Footnote 55

In sum, the judiciary continues to play a central role in implementing Law 9840 effectively. Jurisprudence continues to evolve in a favorable direction for prosecuting politicians under the law. The judiciary’s active role has not only helped to implement the law as initially designed but has also expanded its reach to cover additional modalities such as indirect exchanges and “campaign gifts.” As an additional boost to anti-clientelism efforts, the TSE engages in advertising campaigns.

Summary

Whereas Brazilian politicians previously bought votes with impunity, Law 9840 increased the risk of prosecution associated with this common practice. By classifying vote buying as an electoral infraction, its designers circumvented many complexities that stymie criminal prosecution. Since its enactment, over a thousand politicians have been removed from office for clientelism during campaigns.

As this study has explored, civil society and the judiciary helped enact and implement Law 9840, the first of only four laws by popular initiative passed by the national legislature. Civil society organized the collection of over one million signatures and then, building on its activation during the popular initiative, it improved the law’s implementation through 9840 Committees. As explained by the former head of the Commission on Justice and Peace, “it was an enormous victory for Brazilian democracy because it was a law that came from the bottom up.”Footnote 56 Second, the judiciary developed and publicly supported the initiative, and interpreted the law in a manner that heightened its ability to prosecute politicians. Referring to Law 9840, TSE Justice José Delgado explained: “With every election, jurisprudence is being established that cleans up and increases the rigor of legal proceedings. The judiciary is adapting to what society wants from it.”Footnote 57

A more recent popular initiative, Lei da Ficha Limpa (Clean Slate Law), has sharpened the impact of Law 9840’s punishments. According to this 2010 law, Brazilians cannot serve as candidates for public office for eight years after convictions for specified crimes or being ousted from political office, regardless of whether they can still appeal these convictions.Footnote 58 As a result, distributing benefits during campaigns is now punishable not only by a politician’s ouster but also by the longer-term exclusion from all elected positions. Such a penalty can be especially significant for a career politician. The adoption of Ficha Limpa was facilitated by the advocacy of the CNBB and many other civil society actors who had supported Law 9840 (Reference ReisReis 2013, 68, 80–82), and 94 percent of 9840 Committees surveyed by Melchiori (Reference Melchiori2011, 75) collected signatures of citizens for Ficha Limpa.

Overall, Law 9840 has substantially increased the risk of punishment to politicians who distribute campaign handouts. Yet such changes have by no means extinguished clientelism in Brazil. As survey evidence presented in the introduction suggests, clientelism during campaigns continues despite these punishments. Law 9840 raises the associated costs of strategies such as vote buying or turnout buying, but many politicians still face incentives to engage in electoral clientelism. Moreover, ongoing clientelist relationships are relatively more resilient to this legislation because they are not temporally confined to election periods.