Excessive and uncontrollable worry is a hallmark feature of generalised anxiety disorder (GAD).1 It is typically viewed as a maladaptive emotion regulation strategy that exacerbates fear and anxiety by promoting catastrophic ‘what if’ appraisals about perceived threats and uncertainty.Reference Woody and Rachman2 Pathological worry in GAD has also been specifically linked to the poor discrimination of threat and safety signals, resulting in fear ‘overgeneralisation’: an aberrant learning process whereby safe stimuli or contexts that resemble feared situations become inappropriately perceived as threatening.Reference Lissek, Kaczkurkin, Rabin, Geraci, Pine and Grillon3 Although it is unclear precisely how this relationship manifests (i.e. cause or effect),Reference Lissek, Kaczkurkin, Rabin, Geraci, Pine and Grillon3 there is evidence from brain functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies to suggest that these processes converge at the level of impaired ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) function in people with GAD.Reference Lissek, Kaczkurkin, Rabin, Geraci, Pine and Grillon3, Reference Myers-Schulz and Koenigs4

The vmPFC has been shown to be consistently and preferentially linked to the processing of safety v. threat signals during fear conditioning experiments,Reference Fullana, Harrison, Soriano-Mas, Vervliet, Cardoner and Àvila-Parcet5 an observation that also extends to the processing of safety signals during fear extinction learning and recall,Reference Milad, Wright, Orr, Pitman, Quirk and Rauch6, Reference Phelps, Delgado, Nearing and LeDoux7 fear reversalReference Schiller and Delgado8 and fear generalisation tasks.Reference Lissek, Bradford, Alvarez, Burton, Espensen-sturges and Reynolds9 In these processes, the vmPFC is suggested to inhibit fear in front of safety by encoding a conceptual-affective value of safe v. threatening stimuli.Reference Lissek10, Reference Harrison, Fullana, Via, Soriano-Mas, Vervliet and Martínez-Zalacaín11 Although few studies have examined these processes in GAD, one study has shown that fear overgeneralisation in participants with GAD is accompanied by reduced vmPFC activity, reflecting poorer neural discrimination between threat and safety signals.Reference Greenberg, Carlson, Cha, Hajcak and Mujica-Parodi12 In this study, the magnitude of vmPFC impairment was linked to both higher trait anxiety and comorbid depressive symptoms, leading the authors to suggest that their finding may reflect a ‘broader dysfunction of regulatory skills in GAD’.Reference Greenberg, Carlson, Cha, Hajcak and Mujica-Parodi12 However, whether these findings may also reflect the nature (i.e. healthy v. pathological characteristics) and severity of worry in people with GAD remains unclear.

Aims of the study

The aim of the current study was to test this hypothesised relationship by examining whether the severity of worry in GAD was associated with vmPFC response to safety during differential fear conditioning – a reliable means to evoke the vmPFC processing of safety signals.Reference Fullana, Harrison, Soriano-Mas, Vervliet, Cardoner and Àvila-Parcet5, Reference Harrison, Fullana, Via, Soriano-Mas, Vervliet and Martínez-Zalacaín11 To examine this relationship, we recruited individuals with GAD and a group of healthy controls who demonstrated varied levels of worry, from low to high levels. This recruitment approach allowed us to examine the influence of worry from both a ‘dimensional’ and ‘disorder-specific’ perspective, which is relevant to the ongoing debate about the nature of worry in GAD, and whether it is distinguishable from high levels of worry in healthy populations.Reference Borkovec, Davey and Tallis13, Reference Ruscio14 In addition, despite GAD's high comorbidity with depression, we recruited participants with GAD who were unmedicated and mostly non-comorbid.

Method

Participants and clinical measures

We conducted a large initial screening process to recruit study participants. First, via a secure online system, an advertisement was posted on University platforms (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Universitat Pompeu Fabra and Universitat de Barcelona, campus Bellvitge, all of them in Barcelona). A total of 2500 respondents completed an online version of the Screening Scale for Generalised Anxiety Disorder according to DSM-IV criteria (Carroll and Davidson, Spanish versionReference Bobes, García-Calvo, Prieto, García-García and Rico-Villademoros15). Of these respondents, those with high scores on the screening scale (7–12) and those with mild or low scores (0–6) were grouped as either potential participants with GAD or healthy controls, respectively.Reference Bobes, García-Calvo, Prieto, García-García and Rico-Villademoros15 Individuals who passed all initial exclusion criteria subsequently underwent the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), conducted by an experienced psychiatrist (E.V.) or clinical psychologist (M.A.F.).Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs and Weiller16 This assessment had to be conducted on 332 individuals in order to identify a total of 30 participants who received a primary formal diagnosis of GAD and a total of 60 healthy controls demographically matched to those with GAD in terms of age, gender, handedness and years of education.

Healthy controls were excluded if they had any current or past Axis I psychiatric disorder. Individuals in the GAD group could have another current anxiety disorder – with the exception of post-traumatic stress disorder or obsessive–compulsive disorder – or past depressive episode as long as GAD was the primary diagnosis, but were excluded if they had any other current or past Axis I psychiatric disorder. They were also excluded if they were taking any pharmacological treatment, with the exception of occasional benzodiazepine (or an analogue) treatment (i.e. less than 3 days during the past week or as an hypnotic treatment). An additional exclusion criterion for the GAD group was if they scored below the cut-off of maximum specificity in the Penn State Worry QuestionnaireReference Sandín, Chorot, Valiente and Lostao17 (PSWQ <60) on the day of the scanning. This criterion led to the exclusion of three participants whose symptoms had improved since initial screening. Other exclusions for all participants included the presence of any neurological disorder, misuse of any drug other than nicotine, and the presence of contraindications to MRI. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. Another four participants (healthy controls) were excluded because of technical problems or excessive movement during fMRI (see below). The final study groups included 27 patients with GAD (70% females; mean age 23.00 years, s.d. = 4.47) and 56 healthy controls (66% females; mean age 21.45 years, s.d. = 3.46).

On the scanning day, all participants completed the PSWQ, a measure of a trait-tendency to worry and of symptom severity in GAD. Depressive and anxiety symptoms were assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-2)Reference Sanz, Navarro and Vazquez18 and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HRSA)Reference Lobo, Chamorro, Luque, Dal-Ré, Badia and Baró19 as well as the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.Reference Spielberger, Gorsuch and Lushene20 Demographical and clinical measures were compared between groups by means of the Student's t-test or χ2-test when appropriate. Analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics v20.

Written informed consent was collected from all participants following a complete description of the study. The institutional review board of the University Hospitals of Bellvitge and Hospital del Mar, Barcelona, Spain, approved the study protocol. Participants with GAD were debriefed about the diagnosis, were informed about the need for a clinical follow-up, and were offered a clinical referral on completing the study.

Experimental design

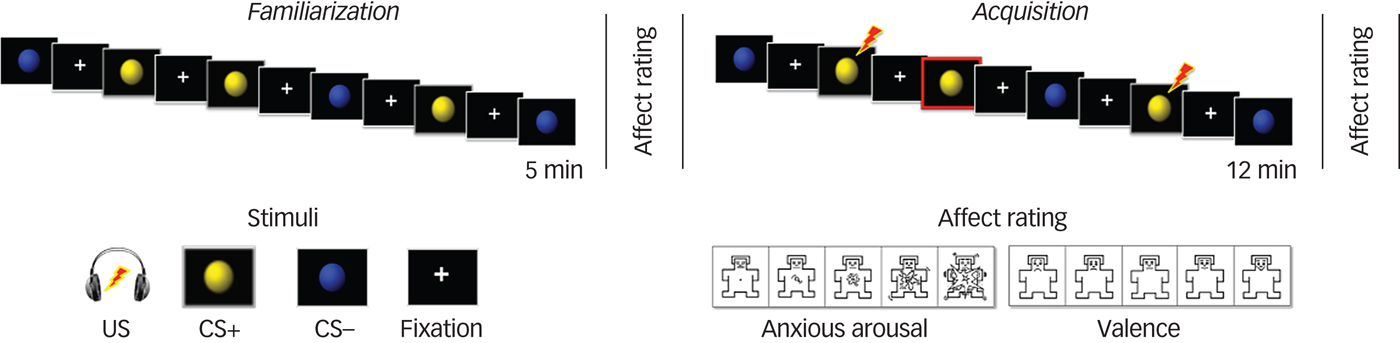

The fMRI differential conditioning paradigm used in this study has been described in detail elsewhere.Reference Harrison, Fullana, Soriano-Mas, Via, Pujol and Martínez-Zalacaín21–Reference Kircher, Arolt, Jansen, Pyka, Reinhardt and Kellermann23 Briefly, prior to scanning, participants were instructed that during the session they would be presented with blue and yellow spheres and asked to rate them in terms of valence/anxious arousal. Once in the scanner but before the experiment, participants were asked to rate the unpleasantness of ‘a sound’ stimulus (the unconditioned stimulus, UCS; aversive auditory noise burst) on an 11-point Likert scale. The stimulus was presented at 95 dB and was increased, if necessary, until a minimum unpleasantness rating of seven was given. The maximum level was 110 dB. The fMRI session then commenced with short localising scans followed by a 12 min (eyes-closed) resting-state acquisition. After the resting state, participants were instructed that a new scan would commence and to be ready to use the hand-held response device.

During the task, the two visual conditioned stimuli (VCS, corresponding to the coloured spheres) were alternatively presented for 2 s during the familiarisation and acquisition phases. During familiarisation, each VCS was presented 16 times in randomised order (32 trials in total) with no presentations of the UCS occurring. During acquisition, the UCS was paired with one VCS (to form the VCS+) and not with the other (to form the VCS−); the VCS (blue/yellow) that was conditioned was counterbalanced across participants. The presentation of the UCS (100 ms duration) occurred 1.9 s after the onset of the VCS+ and co-terminated. The VCS–UCS pairing occurred with a partial reinforcement rate of 50%, which enabled the classification of VCS+ unpaired trials and the subsequent analysis of VCS+ neural responses without UCS confounding: 16 VCS+ unpaired, 16 VCS+ paired and 32 VCS− trials were presented in randomised order. The interstimulus interval between VCS presentations consisted of a white visual fixation cross and ranged between 2.3 to 17.1 s, see Harrison et al.Reference Harrison, Fullana, Via, Soriano-Mas, Vervliet and Martínez-Zalacaín11 Immediately after each phase, participants were asked to rate their experience of bodily anxiety sensations (‘anxious arousal’) to the VCS+ and VCS− on a five-point Likert scale self-assessment manikin (SAM).

Participants also made emotional valence ratings of the VCS+ and VCS− on an equivalent five-point SAM just after each phase, with responses ranging from 1, ‘very unpleasant’ to 5, ‘very pleasant’ (Fig. 1). Upon conclusion of scanning, the UCS was reconfirmed to be moderately-to-highly unpleasant for both groups (11-point scale, controls: mean 7.62 (s.d. = 1.56), range 3–10; GAD participants: mean 7.19 (s.d. = 2.00), range 2–10; t(77) = 1.05, P = 0.30).

Fig. 1 Representation of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex paradigm: familiarisation and acquisition phases and self-assessment manikin assessments.

The task was programmed in Presentation® (Neurobehavioral Systems, Inc) and delivered using MRI-compatible high-resolution goggles and headphones (VisuaStim Digital, Resonance Technology Inc). SAM responses were made using a hand-held optical-fibre response-recording device.

Behavioural analyses

Repeated measures ANOVAs in SPSS were used to analyse subjective rating scores to the task: stimuli (VCS+, VCS−) × group (GAD, controls) during the acquisition phase. The 2 × 2 ANOVA models were estimated separately for arousal and valence scores.

Imaging acquisition and preprocessing

A 1.5 Tesla Signa Excite system (General Electric, Milwaukee, WI, USA) equipped with an eight-channel phased-array head coil and single-shot echoplanar imaging (EPI) software was used. The functional sequence consisted of gradient-recalled acquisition in the steady state (time of repetition, 2000 ms; time of echo, 50 ms; pulse angle, 90°) within a field of view of 24 cm, a 64 × 64-pixel matrix and a slice thickness of 4 mm (interslice gap, 1 mm). Twenty-two interleaved slices, parallel to the anterior–posterior commissure line, were acquired to generate 572 whole-brain volumes, excluding four initial dummy volumes. Imaging data were transferred and processed on a Macintosh platform running MATLAB version 7.14. Preprocessing was performed with Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM8) and involved motion correction, spatial normalisation to the SPM-EPI template (12-parameter affine transformation followed by non-linear transformations) and smoothing using a Gaussian filter (full-width half-maximum, 8 mm). All image sequences were routinely inspected for potential movement or normalisation artefacts. Motion realignment parameters (translation and rotation estimates) were less than 2 mm and 2°, respectively in each plane for all participants finally included in the study. Realignment parameters were included as first-level covariates in the time-series analyses, as described below.

Processing and imaging analyses

Each participant's preprocessed time series was included in SPM first-level general linear model (GLM) analyses. Each event type (VCS−, VCS+ non-paired, VCS+ paired, SAM ratings) was individually coded by specifying the onset of each stimulus presentation as a delta (i.e. stick) function. For the acquisition phase, we specified whether trials occurred during the first or second half of the phase. A high-pass filter (1/128 s) accounted for low-frequency noise, whereas temporal autocorrelations were estimated using a first-order autoregressive model (AR(1)). Realignment parameters of each participant were included in the model. Contrast images corresponding to the task effects of interest, that is, safety v. threat (VCS− v. VCS+ unpaired trials) during acquisition, were estimated for each participant. The opposite contrast (VCS+ unpaired trials v. VCS−) was also estimated. Contrast images were separately estimated for the early and late halves of the acquisition phase in order to examine potential group differences in learning profile.Reference Schiller, Levy, Niv, LeDoux and Phelps24 These contrast images were then carried forward to the second level using the summary statistics approach to random-effects group analyses.

Between-group differences in safety v. threat signal activation were examined via two-sample t-test at the level of the vmPFC using a large predefined mask obtained from Neurosynth.org25 (5978 voxels; 47 824 mm3). Differences were considered significant if surviving P family-wise error(FWE)<0.05 small-volume corrected.

To examine the hypothesised association between worry severity and vmPFC response to the safety (v. threat) signal, and whether worry severity differently modulated vmPFC responses in GAD compared with healthy controls, we conducted an ‘interaction analysis' in SPM. This analysis involved, first, the introduction of participants’ PSWQ score as a specified covariate of interest in the prior two-sample t-test model. Second, we specified a regressor for each group representing the correlation between PSWQ scores and brain response to safety. The subsequent between-group comparison of regression slopes identifies those brain areas with significantly different group correlations between PSWQ and brain responses. For the purpose of the study, we first restricted this analysis to the vmPFC, using the same mask as above. Effects were considered significant if surviving P FWE<0.05 small-volume corrected for the vmPFC mask. To supplement these analyses, whole-brain within-group activation effects and between-group exploratory analyses were also conducted (Supplementary Text 1, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.65).

Results

Clinical and demographic variables

There were no between-group differences in age, gender, years of education or the task version used (yellow or blue spheres as the conditioned stimulus). The GAD group had significantly higher scores on the PSWQ, as well as high levels of depression and anxiety symptoms compared with the healthy controls (Table 1). PSWQ scores in the GAD group were similar to previous studies of help-seeking GAD samples.Reference Seeley, Mennin, Aldao, McLaughlin, Rottenberg and Fresco26 Four healthy controls presented PSWQ scores above the maximum specificity cut-off (>60),Reference Sandín, Chorot, Valiente and Lostao17 but on the clinical interview we ensured that they did not fulfil criteria for the DSM-IV GAD diagnosis. One participant with GAD had a past diagnosis of major depression and three fulfilled criteria for social phobia. Two participants with GAD were receiving occasional psychopharmacological treatment, either with clorazepate or zolpidem.

Table 1 Demographic, clinical and behavioural measurements of the participants

VCS, visual conditioned stimuli.

Behavioural results

Repeated measures ANOVA of subjective arousal and valence ratings indicated successful conditioning in both groups. That is, threat signal was evaluated as significantly more aversive than safety by all the participants (i.e. increased anxious arousal: F(1,81) = 157.02; P < 0.001; ![]() ${\rm \eta} _{\rm p}^2 = 0.66$; decreased positive valence: F(1,81) = 131.57; P < 0.001;

${\rm \eta} _{\rm p}^2 = 0.66$; decreased positive valence: F(1,81) = 131.57; P < 0.001; ![]() ${\rm \eta} _{\rm p}^2 = 0.62$). There was an additional effect of group on anxious arousal, with the GAD group rating both stimuli as generally more aversive compared with healthy controls (F(1,81) = 8.02; P = 0.006;

${\rm \eta} _{\rm p}^2 = 0.62$). There was an additional effect of group on anxious arousal, with the GAD group rating both stimuli as generally more aversive compared with healthy controls (F(1,81) = 8.02; P = 0.006; ![]() ${\rm \eta} _{\rm p}^2 = 0.09$). See Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1 for a full depiction of the results.

${\rm \eta} _{\rm p}^2 = 0.09$). See Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1 for a full depiction of the results.

Imaging results

Threat and safety signal processing

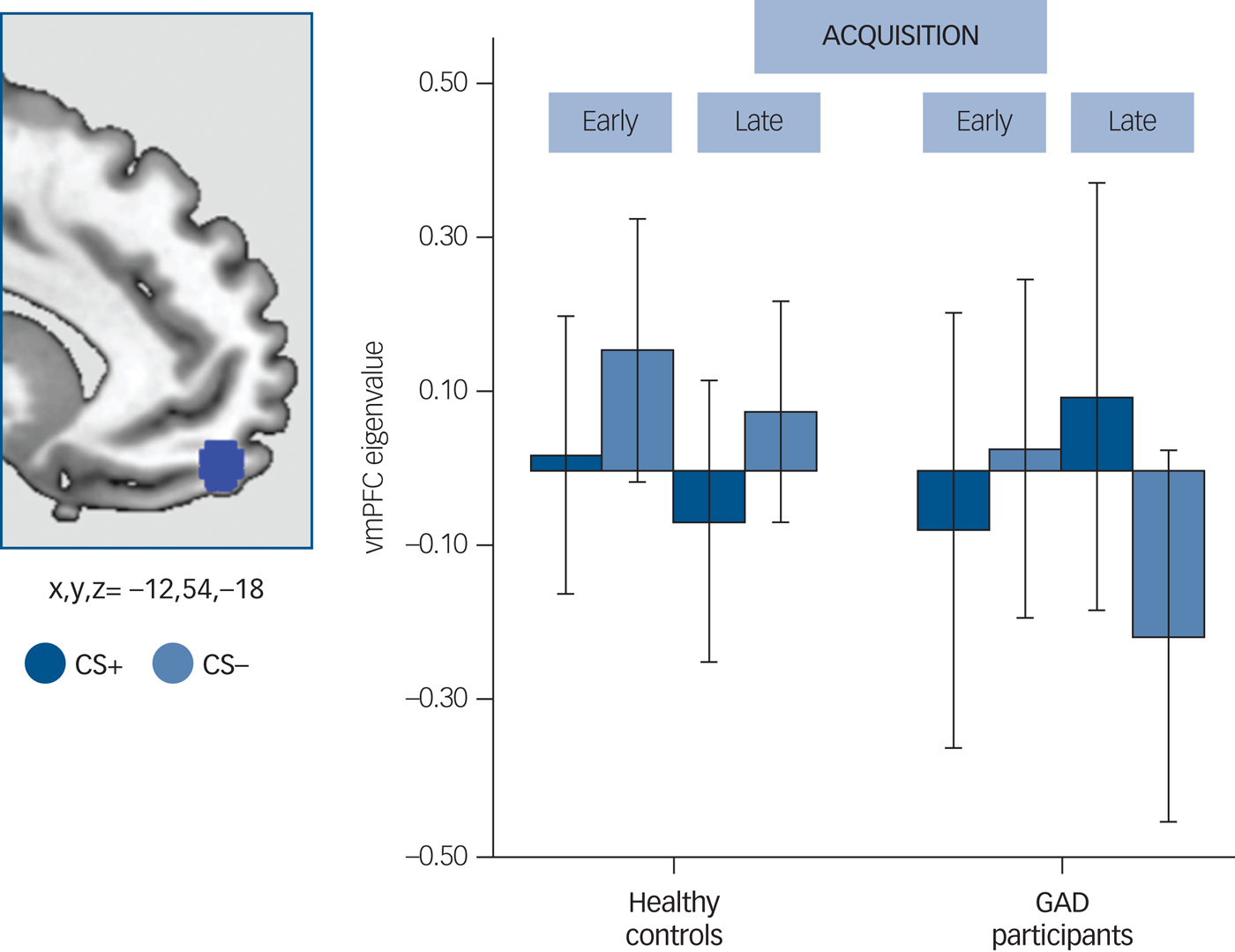

Consistently with our hypothesis, the GAD group demonstrated significantly decreased vmPFC response to the safety signal compared with the healthy controls. This difference was only significant in the late phase of acquisition (x,y,z = −12,54,−18; t = 3.98, P FWE = 0.030, K E = 5540) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Between-group differences in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC).

Left side: a blue 5 mm diameter sphere at the results' peak of between-group differences for the visual conditioned stimuli (VCS)−>VCS+ contrast is overlapped on a sagittal-medial view of the brain. Right side: bar plot representing the extracted eigenvalues (akin to the average of the functional magnetic resonance imaging response within each participant, 5 mm sphere at x,y,z = −12,54,−18) separately for VCS+ (v. implicit baseline) and VCS− (v. implicit baseline) at the results' peak during the acquisition phase. Dark blue: response to the VCS+ during the early and late acquisition phase; little blue: response to the VCS− during the early and late acquisition phase. Error bars are displayed.

The whole-brain within-group activations demonstrated, in healthy controls, an overall pattern of differential safety signal processing (VCS− v. VCS+), including vmPFC activation, that replicates the findings of many past studies.Reference Fullana, Harrison, Soriano-Mas, Vervliet, Cardoner and Àvila-Parcet5 The between-group analysis demonstrated, at a more liberal threshold, reduced activation in the GAD group compared with healthy controls of the anterior region of the medial and ventromedial prefrontal cortex, among other regions (Supplementary Text 2, Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

Modulation by worry

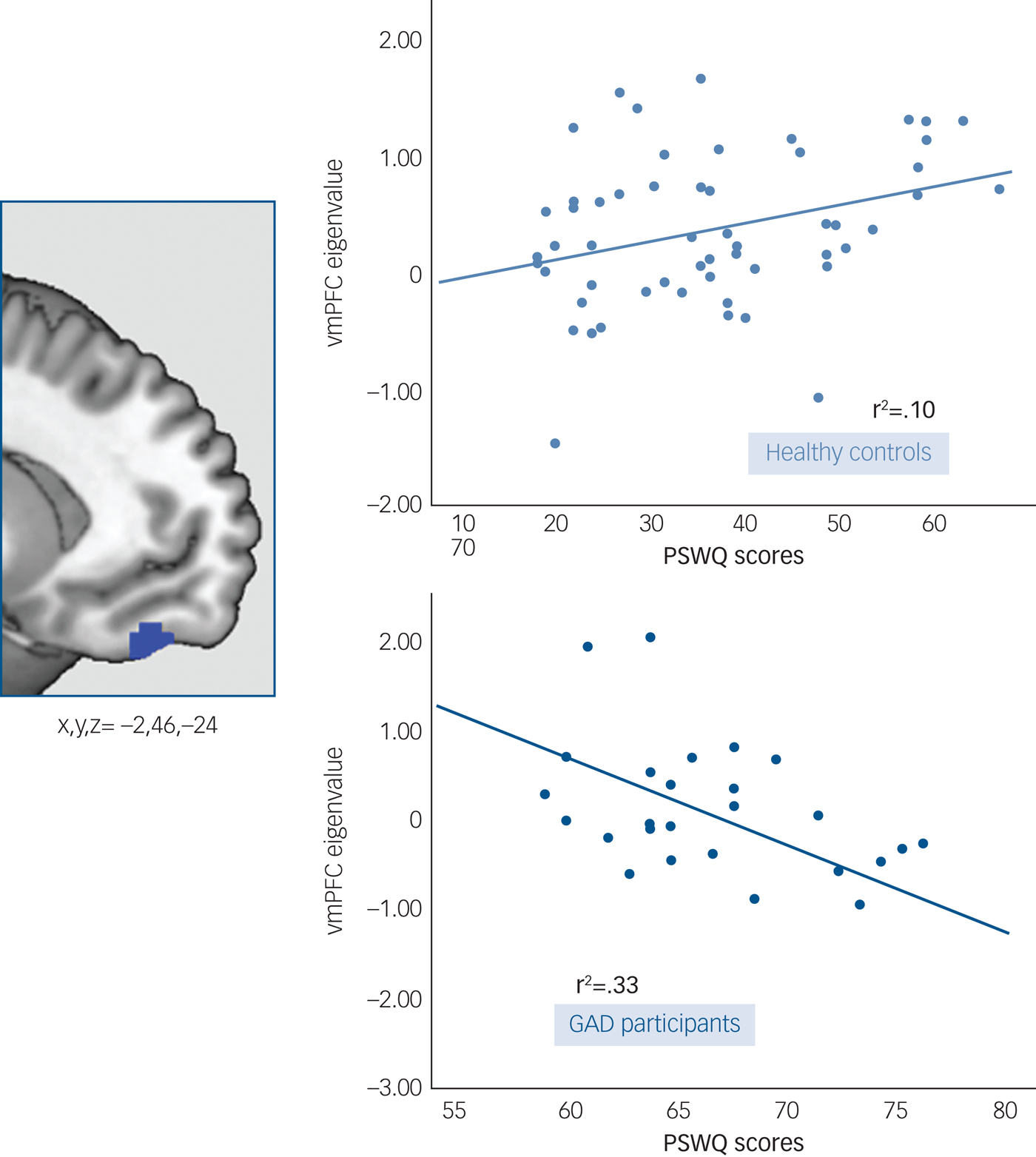

Given that no between-group differences were observed for the early half of the acquisition phase, this analysis was restricted to the late phase. There was a significant between-group (GAD participants v. healthy controls) interaction between PSWQ scores and vmPFC response to the safety signal (x,y,z = −2,46,−24; t = 4.90; P FWE = 0.001, K E = 4547). This resulting cluster was located at the more ventral part of the vmPFC, including the orbitofrontal cortex region. The post hoc within-group correlations showed that these results were driven by a negative correlation between PSWQ and vmPFC in the GAD group, i.e. higher scores on the PSWQ were associated with a decreased response of the vmPFC to the safety signal (r 2 = 0.33, P = 0.002). The opposite association was found in healthy controls, with higher PSWQ scores associated with an increased response to the safety signal (r 2 = 0.10, P = 0.016) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Worry modulation of the vmPFC response to the safety signal. Left side: A blue 5mm diameter sphere at the results’ peak of between-group differences in the interaction analysis between PSWQ scores and vmPFC response to the VCS->VCS+. Right side: Scatter plots and fitted regression lines between PSWQ scores and vmPFC response to the VCS->VCS+ in patients with GAD and healthy controls.

Dots represent extracted eigenvalues (akin to the average of the fMRI response within each participant), for each subject, at the peak of differences (5mm-sphere, x,y,z = −2,46,−24).

We confirmed the above results by creating a new regression model with the same variables of interest, but this time including all the participants independent of group status. We observed a significant negative correlation between PSWQ and the vmPFC response to safety (x,y,z = −2,14,−12; t = 3.99; P FWE = 0.029, K E = 5540). Although this SPM model tests only a linear association between variables, the extracted eigenvalues at the peak of the results were analysed in SPSS to estimate the best curve fit for this association (linear, quadratic). This analysis indicated that the quadratic model (positive correlation between low PSWQ scores and vmPFC response but a negative correlation between high PSWQ scores and vmPFC response) provided the best fit to the data (linear model: adjusted r 2 = 0.15; F = 15.91; P < 0.001; quadratic model: adjusted r 2 = 0.20; F = 11.84; P < 0.001).

Whole-brain exploratory analyses also indicated a significant interaction effect at the level of the vmPFC and anterior cingulate cortex (Supplementary Text 1, Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 3). Across all analyses, the reported differences remained significant after the exclusion of the two participants who had received pharmacological treatment and the three individuals in the GAD group with comorbid social phobia. Finally, in post hoc analyses, we examined potential associations across both groups between global anxiety (HRSA) and depressive symptoms (BDI-2) and vmPFC responses characterised from the primary group analysis and the analysis of associations with PSQW scores. No significant associations were identified (all correlation coefficients between r = −0.24 and r = 0.10 and all P-values between P = 0.43 and P = 0.92).

Psychophysiological validation

All participants completed an outside-the-scanner parallel version of the fear conditioning task using skin conductance response (SCR) to confirm that the fear conditioning task indeed evoked significant changes in sympathetic autonomic arousal (week 2, see Harrison et al Reference Harrison, Fullana, Soriano-Mas, Via, Pujol and Martínez-Zalacaín21). Analyses of this task confirmed that both groups showed successful fear acquisition (i.e. higher response to the VCS+ v. the VCS−) based on their SCR (Supplementary Text 2). The GAD group additionally showed overall reduced SCRs in comparison with controls during the task, confirming previous reports of decreased arousal in GAD.Reference Seeley, Mennin, Aldao, McLaughlin, Rottenberg and Fresco26 Moreover, and despite the successful acquisition of fear in the early phase of acquisition, the GAD group showed a non-significant between-stimuli difference on the late half of acquisition (Supplementary Text 2).

Discussion

Main findings

Worry is a core feature of GAD that may reflect alterations in the function of emotion regulatory neural circuitry. In this study, we tested whether an impairment in safety signal processing exists in the vmPFC in GAD, and whether the severity of healthy and pathological worry was associated with such an altered response. Compared with healthy controls, the participants with GAD showed a deficient recruitment of the vmPFC in response to the safety v. threat signal. Importantly, the severity of worry was found to be associated with vmPFC activity in a disorder-specific rather than trait-dimensional manner.

Comparison with findings from other studies

The present study provides evidence of an altered vmPFC response to safety signal processing in GAD, an alteration that was associated with a lack of vmPFC response to the VCS− compared with the VCS+. These deficits in between-stimuli differentiation are convergent with the observations of Greenberg et al,Reference Greenberg, Carlson, Cha, Hajcak and Mujica-Parodi12 who used a generalisation task to show that female participants with GAD had a flatter vmPFC response to a gradient of safety stimuli (diverse VCS− resembling a VCS+) in comparison with a control group. Although both this study and our study used different fear learning paradigms (i.e. fear conditioning v. fear generalisation), they both show a poor vmPFC-mediated neural processing of safety signals in GAD, and confirm that vmPFC alteration might be detected in diverse threat–safety conditioning scenarios, as suggested from studies in healthy participants.Reference Schiller and Delgado8

Moreover, vmPFC alterations in our study emerged in later conditioning trials, which suggest that the vmPFC impairment is not related to delayed learning of the stimulus contingency in GAD, but to a more intrinsic alteration in its response. This parallels the globally flatter vmPFC response to diverse VCS− observed in Greenberg and colleagues' study.Reference Greenberg, Carlson, Cha, Hajcak and Mujica-Parodi12 Both designs provide information on response to safety and its differentiation from threat, and might be used to understand fear generalisation and overgeneralisation processes that occur in GAD.Reference Lissek10

Worry as a perpetuator of emotional dysregulation

One of the primary aims of this work was to test the hypothesised relationship between vmPFC activity and the severity of worry in participants with GAD and healthy controls. We observed a significant association in the GAD group, which was opposite in direction and stronger than the one observed in healthy controls. In participants with GAD, worry severity predicted poorer vmPFC discrimination of the safety v. threat signals. Although a general association between emotion processing and deficient prefrontal regulatory control has been suggested in GAD,Reference Paulesu, Sambugaro, Torti, Danelli, Ferri and Scialfa27 ours is the first study to demonstrate a neurobiological relationship between the safety response, and by implication fear inhibitory processing, and worry. This result fits with the conceptualisation of worry as a perpetuator of emotional dysregulation, while being used as an avoidance strategy to emotional responses.Reference Borkovec, Davey and Tallis13 Importantly, this association seems to be characteristic of ‘pathological worriers’, as in healthy controls greater worry severity was associated with an increase in the expected normal vmPFC response to the VCS−.Reference Fullana, Harrison, Soriano-Mas, Vervliet, Cardoner and Àvila-Parcet5

A neurobiological differentiation between adaptive and pathological worries

This result is in agreement with the findings of prior work suggesting a differentiated brain network for healthy v. pathological worries, with GAD being associated with a unique and more complex network than in controls – including the vmPFC, the dorsolateral prefrontal and the amygdala.Reference Mohlman, Eldreth, Price, Staples and Hanson28 Taking both results together, these differences in brain activation and connectivity might be associated with the development of two differentiated circuits: an adaptive one supporting worrying as a problem-solving strategy and another representing pathological changes associated with the constant anticipation of negative consequences – a system that would be insufficient to support worrying as an emotional strategy to face threat or uncertainty.Reference Paulesu, Sambugaro, Torti, Danelli, Ferri and Scialfa27 With these results, we suggest the existence of neurobiologically based qualitative differences between the processing of healthy and pathological worries, providing new evidence in favour of a categorical differentiation of healthy v. pathological worry. These findings are particularly interesting considering the current emphasis on identifying neurobiological correlates of symptom dimensions, rather than disorder-specific markers.Reference Cuthbert and Kozak29

Implications

The association between pathological worry and alterations in vmPFC-mediated fear regulation have clinical relevance. Results suggest that the vmPFC has a central role in processing ambiguous safety signals, a dysfunction associated with the overgeneralisation of fear and the maintenance of day-to-day anxiety in patients with GAD.Reference Lissek, Kaczkurkin, Rabin, Geraci, Pine and Grillon3, Reference Lissek10 More generally, these deficits might explain the disturbances in threat-related emotion regulation in patients with GAD, given vmPFC involvement in the flexible value-based response and regulation of emotions.Reference Schiller and Delgado8 In addition, a core deficit in safety processes could explain many of the features of GAD, but also other anxiety disorders – including obsessive–compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, panic disorder and social anxiety disorder – where there is accumulating evidence that dynamic vmPFC processing of safety is impairedReference Harrison, Soriano-Mas, Pujol, Ortiz, López-Solà and Hernández-Ribas30, Reference Etkin and Wagner31 and that medial prefrontal areas might be predictive of psychological treatment outcome.Reference Lueken, Straube, Konrad, Wittchen, Ströhle and Wittmann32

Limitations

Our study has some limitations that should be taken into account. First, we recruited a moderately sized sample of individuals with GAD. We did, however, have relatively homogeneous presentations, with untreated illnesses of short duration. Second, it might be argued that the lack of comorbidities in the GAD group reduces the generalizability of our results. While the diagnosis of GAD is frequently comorbid with depression, and patients are often treated with medications, our results were not confounded by these factors. Importantly, the greater comorbidity seen in clinical samples is considered an artefact of sample selection rather than inherent to the disorder, and the inclusion of non-comorbid participants with GAD might be better seen as a strength of this study.Reference Tinoco-González, Fullana, Torrents-Rodas, Bonillo, Vervliet and Blasco33

Conclusion

In conclusion, despite growing interest in alterations in safety signal processing as part of the pathophysiology of anxiety disorders, there have been few studies in GAD. These results highlight its relevance, including potential treatment-related consequences. For example, the evidenced vmPFC alterations and the associated clinical impairment might be potentially changed in treatments such as cognitive–behavioural approaches that target safety learning. Indeed, improvements in safety learning have been associated with the hampering of new associations with threatReference Rescorla34 and a softening of anxiogenic responses to stressors,Reference Christianson, Fernando, Kazama, Jovanovic, Ostroff and Sangha35 while improvements in vmPFC safety response have been associated with better coping of negative emotions,Reference Wager, Davidson, Hughes, Lindquist and Ochsner36 a better effective top–down emotion regulatory processes,Reference Hefner, Verona and Curtin37 and resilience and controllability in stressful situations.Reference Hartley, Gorun, Reddan, Ramirez and Phelps38 Finally, this knowledge might be additionally used for neuromodulation therapies, which, despite being under investigation, have received great interest because of the direct implication of neural regions in treatment strategies.Reference Bystritsky, Kaplan, Feusner, Kerwin, Wadekar and Burock39

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.65.

Funding

This study was supported in part by the Carlos III Health Institute (PI12/0136, PI12/00273), a LIIRA Program Grant (WS717052) and National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) Project Grant (1025619). E.V. was supported by an Endeavour Research Fellowship, provided by the Australian government, the Department of Education (I.D. 3993_2014) and a Río Hortega fellowship, provided by the Carlos III Health Institute (ISCIII), Spain (CM15/000839). M.A.F. was supported by the Carlos III Health Institute/FEDER, grant (PI16/00144). X.G. was supported by a grant from the Health Department of the Generalitat de Catalunya (Pla Estratègic de Recerca I Innovació en Salut 2016–2020; SLT002/16/00254). C.S.-M. was supported by a Miguel Servet contract from the ISCIII (CPII16/00048). C.G.D. was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) career development fellowship (I.D. 1061757), Australia. B.S. was supported by the German Research Foundation (project numbers STR 1146/8-1). B.J.H. was supported by a (NHMRC) Clinical Career Development Fellowship (I.D. 1124472). CIBERSAM are initiatives of ISCIII.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of the study participants.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.