INTRODUCTION

Mount Taygetos dominates the southern Peloponnese, separating the Laconian and the Messenian plains, as it cuts through the Mani Peninsula (Fig. 1).Footnote 1 Archaeological finds from the area demonstrate that it was inhabited as early as the Protogeometric era (McDonald and Rapp Reference McDonald and Rapp1972, 93, 288 no. 138). The establishment of local polismata, and cultural and economic pressures presumably exerted by neighbouring areas in the Archaic period (Morgan Reference Morgan, Nielsen and Roy1999, 425), as well as the diversity of the landscape and the natural boundaries between agricultural and pastoral lands (Morgan Reference Morgan2003, 169–71), may have defined the borderlines of the territories, dividing the northern and central part of the mountain into two regions:

-

1) The Aigytis region, extending from the Arcadian settlement of Leondari to the Xerilas Valley and the Malevos turning point (Pausanias 8.27.4; 8.34.5; Kolbe Reference Kolbe1904, 374–5; Pikoulas Reference Pikoulas1982–3, 262–3; Christien Reference Christien and Bergier1989, 30; Morgan Reference Morgan, Nielsen and Roy1999, 406; Luraghi Reference Luraghi2002, 53 n. 44).

-

2) The fertile mountainous area of the Dentheliatis, extending from the southern edge of Aigytis to the gorge of Koskaraka (Kolbe Reference Kolbe1904, 366, 375–7; Valmin Reference Valmin1930, 194–5; Pikoulas Reference Pikoulas1991, 279; Steinhauer Reference Steinhauer1988, 223 n. 29; Koursoumis and Kosmopoulos Reference Koursoumis and Kosmopoulos2013, 55–6),Footnote 2 and renowned in antiquity for the famous ‘Denthis wine’ (Athenaeus 1.31c–d; Pikoulas Reference Pikoulas and Pikoulas2009, 138).Footnote 3 This area was of great strategic importance, as it served as the main gateway from Laconia to the fertile Messenian plain, and a major junction of the mountainous road network connecting Laconia, Messenia and Arcadia (Steinhauer Reference Steinhauer1988, 223–5).Footnote 4

Fig. 1. Map of the Dentheliatis (Ager Denthaliatis).

LIMNATIS IN THE DENTHELIATIS: THE LITERARY SOURCES

The Dentheliatis was primarily associated with the famous sanctuary of Artemis Limnatis at the site of Limnai. As with border sanctuaries elsewhere, it is likely that in the early years the sanctuary was a meeting point for people and ethnic groups of the area (Polignac Reference Polignac and Kyriazopoulos2000, 67–70). In the early first century ad Strabo (8.4.9; 6.1.6) points out that, after the death of the Spartan king Teleklos in the Limnatis shrine, followed by the violation of the Spartan virgins who participated in the ritual, the relations of the neighbouring ethnic groups deteriorated dramatically.

Almost two centuries later, in the second century, Pausanias (4.31.3) attests that in the Messenian hinterland, in the vicinity of the kome Kalamai,Footnote 5 there was a chōrion called ‘Limnai’, which was related to the famous sanctuary where the Spartan king Teleklos was murdered. The ancient traveller also refers to the Spartan accusations against the Messenians for violating their virgins and assassinating their king during a common sacrifice at the goddess' festival, in juxtaposition to the Messenians' counter-allegations that young Spartiates were disguised by Teleklos as maidens in order to assassinate the Messenian magistrates (Pausanias 4.4.1–3; 3.2.6; 3.7.4). The incident was regarded as the reason for the outbreak of the First Messenian War and the beginning of a gradual, long-term conquest of Messenia by the Spartiates.Footnote 6 The importance assigned to the sanctuary of Limnatis by ancient Greek authors, and also its role in the history of the area, are clear.

THE DENTHELIATIS IN TURMOIL: A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

The occupation of a great part of Messenia by the Spartiates ended in 370/369 bc, when the Theban general Epameinondas liberated the area and founded the city of Messene (Fig. 2).Tacitus (Annales 4.43.1–3) mentions the issue of dominance over the Ager Denthaliatis and the sanctuary of Artemis Limnatis in detail. In 338 bc Philip II offered the region to the Messenians (Tacitus, Annales 4.43.1; Magnetto Reference Magnetto1997, 293–4; Cartledge and Spawforth Reference Cartledge and Spawforth2002, 13, 53; Luraghi Reference Luraghi2008, 17–18), presumably in order to reinforce the newly founded state against the Spartiates and further delimit Spartan power in the area, by averting them from playing a leading role in the ‘Koinon of the Greeks’ (Steinhauer Reference Steinhauer1988, 221–2, 227). Around 270 bc the Dentheliatis came, once more, under the rule of Sparta (Roebuck Reference Roebuck1941, 62; Magnetto Reference Magnetto1997, 294 n. 15; Luraghi Reference Luraghi2008, 18–9, 256–7 n. 27), whereas in 222 bc, after the battle of Sellasia, Antigonos Doson returned it to the Messenians (Tacitus, Annales 4.43.1; Magnetto Reference Magnetto1997, 293–4; Cartledge and Spawforth Reference Cartledge and Spawforth2002, 53; Luraghi Reference Luraghi2008, 18 nn. 11–12).

Fig. 2. Map of ancient Messenia.

Although Lucius Mummius must have awarded the land to the Messenians in 146 bc, an inscription on the pedestal of Paionios' statue of Nike from the sanctuary of Olympia attests that the Dentheliatis was assigned to the Messenians a few years afterwards, through the arbitration of six hundred Milesian judges (Tacitus, Annales 4.43.3; Dittenberger and Purgold Reference Dittenberger and Purgold1896, no. 52; Dittenberger Reference Dittenberger1917, no. 683; Ager Reference Ager1996, 446–50 no. 159).Footnote 7 The decision of the Romans to assign the area once again to the Messenians may be interpreted in terms of a regional policy which aimed once again at the limitation of Spartan power in the area (Steinhauer Reference Steinhauer1988, 227–8). Nevertheless, things changed in the first century bc after Julius Caesar's decision to reassign the Ager Denthaliatis (the new Roman name for the area) and other areas to Sparta, a decision associated with the need to secure the provision of the Roman army in the campaign against the Parthians (Steinhauer Reference Steinhauer1988, 227–9). After Caesar's death and the battle of Philippi, in which Spartan troops had been deployed by the victors, Octavian and Marcus Antonius confirmed Spartan sovereignty over the ‘Ager Denthaliatis’ (Tacitus, Annales 4.43.1; Steinhauer Reference Steinhauer1988, 221–2; Cartledge and Spawforth Reference Cartledge and Spawforth2002, 87).Footnote 8

In ad 14 the Messenians delegated an embassy to Rome to express the city's grief at Augustus' death, hail Tiberius' enthronement and inform the new Emperor about their complaints over the loss of parts of their land, presumably including the Ager Denthaliatis (Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 41 [1991], no. 328, 40–1).Footnote 9 Shortly after, Atidius Geminus, Praetor of Achaia,Footnote 10 reassigned the area to the Messenians; this decision was strongly contested by the Spartiates, who appealed in ad 25 to the Roman Emperor and the Senate requesting arbitration. Spartan and Messenian delegates supported their claims by calling upon myths, texts and monuments erected in the shrine of Limnai, as well as their recent history; in the end, the region was given to the Messenians (Steinhauer Reference Steinhauer1988, 219–32; Cartledge and Spawforth Reference Cartledge and Spawforth2002, 127; Luraghi Reference Luraghi2008, 21–3 n. 30). This appeal has been interpreted as the last effort of the Spartiates to regain control over the southern Peloponnese (Steinhauer Reference Steinhauer1988, 223).

A fragmentary stele from the time of Vespasian,Footnote 11 found in the excavation of Messene, records the final(?) demarcation of the borders between Messenia, Laconia and the established territory of the Eleutherolaconian League, with boundary-markers incised on rocks along the ridgeline of Mount Taygetos. The text also records a sanctuary of Artemis Limnatis, located above the natural boundary of the Choireios Nape gorge (Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1431; Reference Kolbe1904, 364–78; Steinhauer Reference Steinhauer1988, 229; Luraghi Reference Luraghi2008, 17–27).Footnote 12

VOLIMNOS: MISCELLANEOUS FINDS FROM THE AREA

As ancient authors and inscriptions attest, the sanctuary of Artemis Limnatis was located on the steep slopes of Mount Taygetos, somewhere along the Laconian–Messenian borderline. As early as the eighteenth century, modern historians and archaeologists were attracted by its apparent importance and therefore began to investigate the area in search of it.

The earliest modern reference to the sanctuary is noted on Regas Pheraios' Balkan chart, the so-called Charta, published in 1797 (Karaberopoulos Reference Karaberopoulos1998, map 2). Thirty-eight years later, the Prefect of Messenia, Pericles Zographos, reported to Ludwig Ross, the General Ephor of Antiquities in Athens, the discovery of a small church at a remote site called ‘Volimnos’;Footnote 13 the site is located above the gorge of Langada and the old road from Kalamata to the villages of Megali Anastasova (modern Nedousa) and Sitsova (modern Alagonia), at an altitude of approximately 960 m above sea level (Fig. 3). Inscriptions found in the area documented the cult of Limnatis (Ross Reference Ross1841, 5–15).Footnote 14

Fig. 3. The valley of Volimnos and the Kapsocherovoloussa chapel. View from the north-east (photo S. Koursoumis).

In the twentieth century, Protogeometric potsherds were collected at Volimnos by members of the Minnesota Messenian Expedition,Footnote 15 as well as other clay vessels and sherds dating from the Archaic, Classical and Hellenistic periods.Footnote 16 A substantial number of clay, metal and ivory objects, also brought to the Archaeological Museum of Messenia (AMM), have been interpreted as votive objects offered to the goddess of the sanctuary. A detailed catalogue of them, first published here, affirms the continuity of the cult in the area from the eighth century bc to the Hellenistic era.

Miscellaneous objects

This incoherent group of objects comprises: a male terracotta figurine with raised arms,Footnote 17 a fragment of a bone four-faced seal (seventh century bc),Footnote 18 a conical spindle whorl of steatite,Footnote 19 a miniature lead object, probably a pendant (mid-seventh century bc),Footnote 20 a silver bead,Footnote 21 and a silver earring in the shape of a winding snake.Footnote 22

Bronze objects

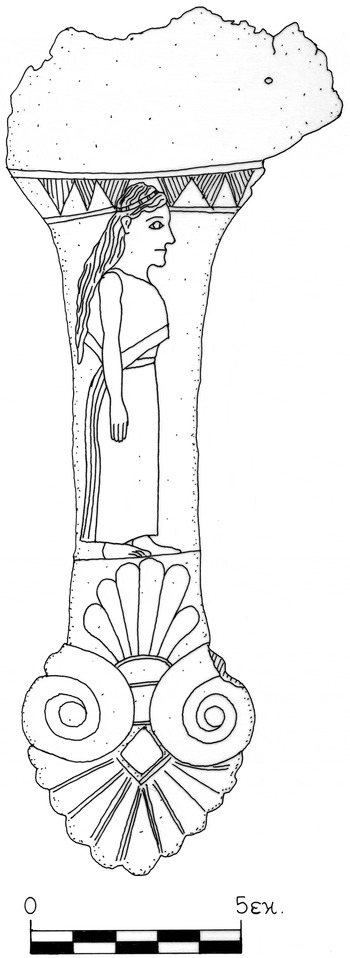

This is the largest group of objects delivered from the area, consisting of a horse figurine (late eighth century bc) (Fig. 4),Footnote 23 six fragmentary pins (Late Geometric period) (Fig. 5),Footnote 24 two sections of pins (Late Geometric/Early Archaic period),Footnote 25 the head of a shoulder pin (first half of the seventh century bc) (Fig. 6),Footnote 26 a bronze figurine of a standing lion, part of a brooch (late seventh/early sixth century bc) (Fig. 7),Footnote 27 a bronze figurine of a siren or harpy wearing a polos, standing on a fibula plaque (early sixth century bc) (Fig. 8),Footnote 28 a bronze handle in the shape of two detached snakes, most probably from an oinochoe (sixth century bc) (Fig. 9),Footnote 29 a bronze cymbal in the shape of a shield (late sixth/fifth century bc) (Fig. 10),Footnote 30 a bronze die (Fig. 11),Footnote 31 a bronze miniature bell,Footnote 32 the bezel of a bronze ring,Footnote 33 a bronze bead,Footnote 34 a miniature bronze lion figurine, probably a pendant of the late Archaic period,Footnote 35 and a fragmentary handle of a bronze mirror bearing the incised depiction of a young woman dressed in a peplos (sixth century bc) (Fig. 12).Footnote 36

Fig. 4. Archaeological Museum of Messenia M13. Horse figurine, 8th century bc (photo V. Georgiadis).

Fig. 5. Archaeological Museum of Messenia M41α–στ. Bronze pins, late 8th century bc (photo S. Koursoumis).

Fig. 6. Archaeological Museum of Messenia M40. Head of shoulder pin, 7th century bc (photo Chr. Sgouropoulou).

Fig. 7. Archaeological Museum of Messenia M12. Bronze figurine of a standing lion, part of a brooch, 7th–6th century bc (photo V. Georgiadis).

Fig. 8. Archaeological Museum of Messenia M20. Bronze figurine of a siren, part of a brooch, 6th century bc (photo V. Georgiadis).

Fig. 9. Archaeological Museum of Messenia M23. Handle of a bronze oinochoe, 6th century bc (photo V. Georgiadis).

Fig. 10. Archaeological Museum of Messenia M39. Bronze cymbal, 6th–5th century bc (photo S. Koursoumis).

Fig. 11. Archaeological Museum of Messenia M54. Bronze die (photo V. Georgiadis).

Fig. 12. Archaeological Museum of Messenia M32. Bronze mirror with incised decoration, 6th century bc (drawing Y. Nakas).

Furthermore, there is a bronze mirror from the early fifth century bc, bearing the following inscription (Figs. 13 and 14): Footnote 37

-

Λιμνάτιο[ς]· Φιλίπ

α μ' ἔθεκες

α μ' ἔθεκες -

(I belong) to Limnatis; Philippa dedicated me

The inscription was written in the Laconian/Messenian alphabet, while the name Philippa is likely to be of Messenian origin.Footnote 38

Other objects recovered from Taygetos, bearing inscriptions in the local alphabet, have also been associated with the Volimnos sanctuary (Luraghi Reference Luraghi2002, 54 n. 49; Reference Luraghi2008, 123 n. 78):

-

(a) A bronze pin from Mystras from the sixth century bc (Le Bas Reference Le Bas1844, 722, pl. 6 no. 18; Foucart Reference Foucart1870, 78 no. 162; Fränkel Reference Fränkel1876, 28–9; Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 226; Robert Reference Robert1969, 1682–3; Gengler Reference Gengler2009, 55–8, 63–5, figs. 2, 6):

-

Πρι

νθὶς ἀνέθεκε τᾷ Λιμνάτι

νθὶς ἀνέθεκε τᾷ Λιμνάτι -

Prianthis dedicated (this) to Limnatis

-

-

(b) Two bronze inscribed cymbals, probably from the mid-sixth century bc:Footnote 39

-

(i) Λιμνάτις

Limnatis

-

(ii) Ὁπωρὶς ἀνέθεκε Λιμνάτι

Hoporis dedicated (this) to Limnatis

-

-

(c) An Archaic bronze mirror (Oberländer Reference Oberländer1967, 44 no. 52; Stibbe Reference Stibbe1996, pl. 12; Luraghi Reference Luraghi2008, 124 n. 74):

-

Λιμνάτις

-

Limnatis

-

The bronze artefacts from Volimnos mentioned above, as well as other objects recorded as having been found in Taygetos, are probably products of local workshops (Herfort-Koch Reference Herfort-Koch1986, passim).Footnote 40 These luxurious items, identified as votive offerings to Artemis Limnatis, document unbroken activity from the Late Geometric until the Late Hellenistic period at a sanctuary of great importance. It is very likely that the cult continued uninterrupted in Roman times, as further documented by inscribed architectural remains built into the walls of the chapel of Kapsocherovoloussa.

Inscribed architectural members

The chapel of Panayia Volimniotissa or Kapsocherovoloussa is built amidst ancient architectural remains, on a small terrace at Volimnos to the north-east of the fertile valley.Footnote 41

Only five out of the seven inscriptions published by Ludwig Ross, Philippe Le Bas and Paul Foucart can nowadays be seen on the southern and western facades of the chapel, where they were incorporated by modern constructors (Ross Reference Ross1841, 5–10; Foucart Reference Foucart1870, 147–9 nos. 295–300).Footnote 42 In the south-western corner of the church the inscription Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1378 was identified, inscribed on a small fragment of a blue-grey marble spolion (Fig. 15):Footnote 43

-

ITAṂ[---]

Though the restoration of the text remains problematic,Footnote 44 the form of the letters suggests a date in the fourth century bc or even later.Footnote 45 It is worth mentioning that, according to Tacitus (Annales 4.43.2), the Messenians maintained in the presence of the Emperor that all texts written in stone in the sanctuary of Limnatis were inscribed by them, that is presumably after 338 bc when the area was assigned to them by the Macedonians.

Just below it, the inscription Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1376 was identified, inscribed on a marble block. The stone is adorned with a cymatium, bearing on its narrow (i) and long (ii) sides the following inscriptions (Fig. 15):Footnote 46

-

(i) θ]εᾶς Λιμνάτιδ[ος]

θε]ᾶς Λιμνά[τιδος]

of the goddess Limnatis

of the goddess Limnatis

-

(ii) B]ορθίῃ θεῷ - - - - - - - Λ[ι]μ[νατ - -]

-

Αὐρ(ηλία) Ἑλιξὼ ἀγωνοθέτης θεᾶς

ι

ι

τ[ιδος]

τ[ιδος]To goddess Vorthia - - - - - - - Limnatis

Aur(elia) Helixô was agonothetes of the goddess Limnatis

The epithet Vorthia Footnote 47 (= Orthia), the name of the Spartan goddess, which later became an epithet for Artemis,Footnote 48 indicates that the goddess of Volimnos shared the attributes of the patron goddess of both the Spartiates and the Messenians.Footnote 49 It was the watchful eye of Orthia that oversaw the athletic and dance contests of the epheboi in Sparta (Pausanias 3.11.9; Xenophon, Hellenica 6.4.16; Plutarch, Vitae Parallelae, Lycurgus 21.2; Pollux, Onomasticon 4.107; Brelich Reference Brelich1969, 138–40; Lo Monaco Reference Lo Monaco, Rizakis and Lepenioti2010, 315). As in Sparta, so in the Limnatis-Vorthia sanctuary at Volimnos, games were probably funded by the agonothetes Aurelia Helixô,Footnote 50 a woman of Greek origin who undertook the magistracy and was authorised to supervise athletic or artistic contests held in the sanctuary.Footnote 51 The form of the letters of the text suggests a date in the late second/early third century ad.

In the western facade of the church the inscription Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1375 was also located inscribed on a marble block adorned with a moulding (cymatium) (Ross Reference Ross1841, 9–10; Foucart Reference Foucart1870, 148 no. 298; Brulotte Reference Brulotte1994, 237; Zunino Reference Zunino1997, 36 T12) (Fig. 16):Footnote 52

-

Ἔτους

μθʹ Αὐρ(ήλιος) Πρεῖμος

μθʹ Αὐρ(ήλιος) Πρεῖμος -

[ἀ]γωνοθέτης θεᾶς Λιμνάτιδος

-

In the year 249 Aur(elios) Preimos

-

agonothetes of the goddess Limnatis

Based on the Actian era (31 bc), the date given above is ad 218. The Roman name Aurelios Preimos (Rizakis, Zoumbaki and Lepenioti Reference Rizakis, Zoumbaki and Lepenioti2004, 499 MES 81) is also attested in an ephebic catalogue from ad 246 from ancient Korone (Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1398, 61; Rizakis, Zoumbaki and Lepenioti Reference Rizakis, Zoumbaki and Lepenioti2004, 499 MES 80).Footnote 53 However, the Koronian Preimos, an ephebe in ad 246, was certainly younger than the agonothetes of Limnatis, and presumably a relative.

On an oblong architectural fragment, a marble block adorned with a narrow cymatium now serving as the southern door jamb of the church, Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1377 was located (Fig. 17):Footnote 54

-

θεᾶς Λειμνάτειδ[ος]

-

of the goddess Limnatis

The form of the letters suggests a date in the late second/early third century ad.

During the most recent visit of the author to the area, an inscribed, fragmentary marble plaque was discovered encased in the lintel of the door of the chapel of Kapsocherovoloussa (Fig. 18):Footnote 55

-

Ἀρχιπ <π> ο[---]

-

Archip <p> o

The form of the letters suggests a date in the Roman period.Footnote 56 The name Ἄρχιππος is quite common in the Greek world and especially in the Peloponnese.Footnote 57 In Hellenistic Messenia it is recorded at Abia (Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1351), as well as in Messene (Klaffenbach Reference Klaffenbach1932, no. 31), while it was common in Sparta and Laconia during the Hellenistic and Roman periods (Klaffenbach Reference Klaffenbach1932, no. 137; Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, nos. 611, 96, 899a–b, 211, 50, 95, 127; Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 11 [1950], nos. 570, 562, 610, 545).

Three other published inscriptions (Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, nos. 1373, 1374 and 1374a), reported to have been carved on a two-faced marble epistyle encased in the walls of the chapel, were unfortunately not found.

Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1373:

-

- - - - τα . . σεβαστο[ῦ υἱ]ός - - - -

-

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

-

- - νος σεβαστοῦ, θεοῦ σεβαστοῦ - - -

-

- - - - - - - σεβ[αστο - - - - -]Footnote 58

-

- - - - ta . . son of sebastos

-

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

-

of - - on sebastos, of god sebastos

-

- - - - - - - sebasto - - - - -

The recurrent sebastos (latin augustus) is an adjective commonly used for the invocation of Roman emperors and members of the Julio-Claudian dynasty in general by the Greeks.Footnote 59

Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1374:

-

Xάρτος Eὐθυκλέος ἱερεὺς Ἀρτέμιτος.

-

Θεοξενίδας Eὐθυκλέος [ἱε]ρε[ὺς Ἄρ]τέμιτος

-

Nικήρατος Θέωνος. Στράτ[ων Σ]τράτ[ω]νος

-

Chartos son of Euthykles priest of Artemis

-

Theoxenidas son of Euthekles priest of Artemis

-

Nikeratos son of Theon. Straton son of Straton

The inscription may be identified as an honorary decree, honouring priests who undertook magistracies in the Limnatis sanctuary.Footnote 60 The names of the two priests of Artemis, Chartos and Theoxenidas, are not attested elsewhere in Messenia or Laconia.Footnote 61 Though the name Euthykles is attested in Laconian inscriptions (Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, nos. 92, 209; Fraser and Matthews Reference Fraser and Matthews1997, 165),Footnote 62 there are no other indications that he was of Laconian origin. On the other hand, Nikeratos and Straton were probably Messenians,Footnote 63 as they should be identified with two religious magistrates in Messene, the Gerontes tēs Oupēsias, supervising the cult of Artemis Orthia-Phosphoros (Orlandos Reference Orlandos1965, 116–21; Robert and Robert Reference Robert and Robert1966, 378–80; Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 23 [1968], no. 208).Footnote 64 Furthermore, a donor bearing the name Nikeratos Theonos is attested in a decree of the Augustan period from Messene (Orlandos Reference Orlandos1959, 170–3; Robert and Robert Reference Robert and Robert1966, 375–7; Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 23 [1968], no. 207).Footnote 65

Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1374a:

-

Ἀβεατῶν πόλις - - - - - - | ἐπὶ

-

Μόσσχου τοῦ Μεν - - - - - - - -

-

. . . . τα - - - - - - - - - -

-

The city of the Abeates - - - - - -| when (eponymous magistrate was)

-

Mosschos son of Men - - - - - - - -

-

. . . . ta - - - - - - - - - -

The text (Foucart Reference Foucart1870, 147 no. 296; Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1374a; Brulotte Reference Brulotte1994, 237) is probably part of an honorary decree, while MosschosFootnote 66 was likely an eponymous magistrate of the Messenian city of Abia.Footnote 67

Finally, the inscribed base Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 39 (1989), no. 388, found at Volimnos and transferred to the Kalamata Archaeological Museum, bears the following inscription:Footnote 68

-

[ - - - - - - ]οιος Ω T [ - - - - - - - - - ]

-

[- - - ἀγων]οθέτης Ἀρτέ[μιδος - - -]

-

ἐκ τῶν εἰδίω[ν]

-

- - - - - - oios O T - - - - - - - - -

-

- - - agonothetes of Artemis - - -

-

at his own (expense)

Apart from Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1378, which is probably earlier, the rest of the inscribed fragments should definitely be dated to the Roman period. At least two (Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, nos. 1374, 1374a), or even three (Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1373), should be dated to the first century ad. The former two may well be dated after ad 25, when the Limnatis sanctuary and the Ager Denthaliatis came under the rule of the Messenians, in accordance with the Emperor's and Senate's decision. This suggestion is further supported by reference to the two Messenian Gerontes tēs Oupēsias, the priests Nikeratos and Straton, in an honorary decree of ad 42 from Messene (Orlandos Reference Orlandos1962, 102 and pl. B; 1976, 32; Robert and Robert Reference Robert and Robert1966, 378–80; Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 23 [1968], no. 208; Moretti Reference Moretti1987–8, 249; Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 38 [1988], no. 337; Brulotte 1994, 248–50; Themelis Reference Themelis, Simantoni-Bournias, Laimou, Mendoni and Kourou2007, 523).Footnote 69 The presence of Messenian magistrates, representing at least two (Messene and Abia)Footnote 70 and presumably three (Korone) (Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1375) Messenian cities, may be interpreted in terms of an established Messenian sovereignty over the area after Augustus' death, and apparently as late as the time of Vespasian. This assumption is further supported by the restoration of the third line of the inscription Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1373 suggested by P. Foucart (Reference Foucart1870, 147 no. 295);Footnote 71 therefore it should probably be dated to the mid-first century ad.Footnote 72 The references to the Emperors and in general the Roman imperial family may well be associated with the institution of the imperial cult in the sanctuary and the area,Footnote 73 yet ‘the border between civic and religious honours cannot be easily determined, because it did not exist for the ancient Greeks’ (Camia and Kantirea Reference Camia, Kantirea, Rizakis and Lepenioti2010, 381).

Furthermore, at least four inscriptions probably date to the second/third century ad (Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, nos. 1375, 1376A–B, 1377; Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 39 [1989], no. 388). The former three have been inscribed on almost identical marble blocks, probably sections of a marble cornice. All fragments bear the same narrow cymatium – a bead-and-reel form, placed on a rectangular band. The type of moulding is rather unusual, but a chronology after the mid-second century ad seems likely.Footnote 74 Apparently, all blocks are parts of a single monument on public display, on which the names of the agonothetai were inscribed, in order to be honoured and viewed by everyone.

Fig. 13. Archaeological Museum of Messenia 872. Bronze inscribed mirror, early 5th century bc (photo V. Georgiadis).

Fig. 14. Archaeological Museum of Messenia 872. Bronze inscribed mirror, early 5th century bc (drawing Y. Nakas).

Fig. 15. Chapel of Kapsocherovoloussa (south facade). Inscribed architectural fragments. Above: Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1378; below: Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1376B (photo V. Georgiadis).

Fig. 16. Chapel of Kapsocherovoloussa. Inscribed architectural fragments (west facade). Above: Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1376A; below: Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1375 (photo D. Kosmopoulos).

Fig. 17. Chapel of Kapsocherovoloussa. Inscribed architectural fragment (west facade). Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1377 (photo S. Koursoumis).

Fig. 18. Inscribed marble plaque from the chapel of Kapsocherovoloussa (photo S. Koursoumis).

Architectural remains

Architectural remains and fragments are abundant in the Volimnos area.Footnote 75 A few of them were built into the walls of the chapel, while the rest remain either on the terrace or scattered on the mountain. The majority of them are constructed of local, blue-grey limestone that was extracted in the area (Fig. 19).Footnote 76 The average dimensions of the blocks (0.50 × 0.50 × 1.30 m) indicate one or more architectural constructions of substantial dimensions (Fig. 20).Footnote 77 A semicircular pedestal, probably an exedra, made of local limestone, was also discovered on the slope to the south of the terrace.Footnote 78

Fig. 19. Volimnos. Quarried bedrock, on the upper terrace (photo S. Koursoumis).

Fig. 20. Chapel of Kapsocherovoloussa. Octagonal column shaft amidst architectural fragments (photo D. Kosmopoulos).

Two column shafts have been located in the area: one at the foot of the slope to the south-west of the terrace, and another standing reversed beside the south-eastern corner of the church. Made of local blue-grey limestone, the shafts belong to two separate, octagonal columns (Figs. 20, 21).Footnote 79 Moreover, a fragment of an octagonal capital, preserving part of the abacus, the echinus and the hypotrachelium, was found next to the church and originally associated with the columns (Fig. 22).Footnote 80 A date in the fifth century bc is suggested for themFootnote 81 and consequently for the structure they belonged to.Footnote 82

Fig. 21. South-west slope. Octagonal column shaft (photo D. Kosmopoulos).

Fig. 22. Chapel of Kapsocherovoloussa. Fragmentary octagonal column capital (photo S. Koursoumis).

At this point, it is rather tempting to recall Tacitus' note, based on the Spartan assertion that the Limnatis temple had been built by their ancestors, presumably before 338 bc when the Dentheliatis was initially assigned to the Messenians (Tacitus, Annales 4.43.1),Footnote 83 and in accord with Strabo's reference (8.4.9) that the temple was erected by the Spartiates.

SANCTUARIES AND HOROI IN A ‘NO MAN'S LAND’

The discovery and identification of boundary stones along the ridge of Mount Taygetos, also documented in Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1431, apparently provide an answer to the question of the sanctuary's precise location. Extensive surveys carried out in the area have identified at least 12 horoi:Footnote 84 the northern horos was discovered in the Malevos area, at the northern edge of the Ager Denthaliatis and the central section of Taygetos, three others to the east of Sitsova (modern Alagonia) (Ross Reference Ross1841, 2–4; Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1372 [= Dittenberger Reference Dittenberger1920, no. 935]; Pernice Reference Pernice1894, 351–5), and eight on the ridge of Mount Paximadi, to the south of the Langada Gorge (Kolbe Reference Kolbe1904, 364–78; Giannoukopoulos Reference Giannoukopoulos1953, 7–12, pls. 1–3; Koursoumis and Kosmopoulos Reference Koursoumis and Kosmopoulos2013, 63–9, figs. 5–7b). It is worth noting that the southern boundary stone was discovered on the peak of Neraidovouna, above the Koskaraka/Rindomo Gorge, at the southern edge of Mount Paximadi, approximately 17.5 km to the south of the northern horos (Figs. 1, 23, 24) (Koursoumis and Kosmopoulos Reference Koursoumis and Kosmopoulos2013, fig. 9).

Fig. 23. Map of central Taygetos. The located boundary stones of Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1431.

Fig. 24. Mount Paximadi (central Taygetos). The horoi at (a) Voidolakoula and (b) Diassela (photo D. Kosmopoulos).

As the Messene inscription states that the boundary line ended above the Choireios Nape gorge, the Koskaraka gorge should be identified with the ancient Choireios Nape. On the other hand, the Limnatis sanctuary recorded in the Messene inscription was probably located within the vicinity of the Neraidovouna horos, overlooking the gorge (Koursoumis and Kosmopoulos Reference Koursoumis and Kosmopoulos2013, 74).Footnote 85 Valmin (Reference Valmin1930, 187–90, figs. 36–9) placed the sanctuary of Limnatis on a fortified hill over the Koskaraka gorge, a few kilometres away from Neraidovouna, near the modern village of Brinda (modern Voreio Gaitson).Footnote 86 Apparently, as the Ager Denthaliatis and the sanctuary at Volimnos had been incorporated into the Messenian region after ad 25, a second sanctuary of Limnatis must have been established in the area, to the south of Neraidovouna, above the Koskaraka gorge, marking the new borders between the Messenians and the Eleutherolaconian League.Footnote 87

WORSHIPPING LIMNATIS

Artemis was a prominent goddess in the Greek religious system. In the southern Peloponnese, her name has been identified on Linear B tablets from the Mycenaean Palace of Pylos (Ventris and Chadwick Reference Ventris and Chadwick1956, 125–7; Zunino Reference Zunino1997, 33; Weilhartner Reference Weilhartner2005, 113, 120, 173; Bendall Reference Bendall2007, 248–9), next to a name which has been interpreted as Orthia (Ventris and Chadwick Reference Ventris and Chadwick1956, 277–9; Zunino Reference Zunino1997, 52–3). Pausanias mentions that Artemis played a critical role in the outcome of the conflict between Messenia and Laconia, showing her displeasure towards the Messenians in crucial moments of the warfare (Pausanias 3.18.8; 4.13.1; 4.14.2; 4.16.9–10; Papachatzis Reference Papachatzis1979, 383–5 n. 2). After 369 bc, Artemis was worshipped all over Messenia with several epithets: in Messene as Orthia-Phosphoros-Oupesia (Orlandos Reference Orlandos and Jantzen1976, 32–5, figs. 21–4; Brulotte Reference Brulotte1994, 240–51; Themelis Reference Themelis and Hägg1994, 101–22; Chlepa Reference Chlepa2001, 13–67, fig. 2; Themelis Reference Themelis2002, 74–6, 85–7, figs. 56–60, 72–6; Zunino Reference Zunino1997, 56–61),Footnote 88 Limnatis (Le Bas Reference Le Bas1844, 422–5; Reinach Reference Reinach1888, 134–8, pls. 1–4; Brulotte Reference Brulotte1994, 253; Zunino Reference Zunino1997, 61–6; Themelis Reference Themelis2004, 143–54; Müth Reference Müth2007, 211–1 6; Solima Reference Solima2011, 203–4) and Laphria (Pausanias 4.31.7–8; Brulotte Reference Brulotte1994, 246–7; Zunino Reference Zunino1997, 62–3; Themelis Reference Themelis2002, 139–40, fig. 84; Themelis Reference Themelis2004, 152–3; Solima Reference Solima2011, 204–6), and in philo-Laconian Thouria as Oupesia (Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 23 [1968], no. 208).Footnote 89 In northern Messenia, along the Arcadian–Messenian borderline, an Archaic temple was erected and presumably dedicated to Artemis Dereatis/Eleia (Valmin Reference Valmin1930, 122–4; Koursoumis Reference Koursoumis2012, 1–16). The goddess was worshipped as Paidotrophos in Korone (Pausanias 4.34.4–5; Farnell Reference Farnell1896–1909, 463, n. 70; Brulotte Reference Brulotte1994, 232–3; Solima Reference Solima2011, 197–8), while her cult is also attested in Kolonides (Head Reference Head1911, 432–3) and Mothone (Pausanias 4.35.8; Imhoof-Blumer and Gardner Reference Imhoof-Blumer and Gardner1964 73 no. 3, xiii pl.; Brulotte Reference Brulotte1994, 253). In Laconia her cult was also popular throughout the whole region, including Sparta and its periphery.Footnote 90

Artemis bearing the epithet Limnatis was associated with lakes, wetlands, springs, rivers and swamps (Farnell Reference Farnell1896–1909, 427 and nn. 1–2; Nilsson Reference Nilsson1967, 493; Calame Reference Calame1997, 143; Morizot Reference Morizot, Docter and Moormann1999, 270–1).Footnote 91 It should be underlined that the sanctuaries of Limnatis were usually located in remote, disputed, mountainous areas, overlooking cliffs and gorges, in order to emphasise her role as a guardian of boundaries (Sinn Reference Sinn1981, 25–71; Morizot Reference Morizot, Docter and Moormann1999, 270–1; Polignac Reference Polignac and Kyriazopoulos2000, 66, 75; Lo Monaco Reference Lo Monaco, Rizakis and Lepenioti2010, 311). The remark by Strabo (8.4.9) that her sanctuary on Taygetos gave its name to the site of Limnai in Sparta where the Orthia sanctuary was located, and also the Spartan assertions concerning the erection of the Limnatis temple (Tacitus 4.43.1), apparently reflect the strong influence of the Spartan patron goddess in the area and designate Limnatis as her alter ego (Steinhauer Reference Steinhauer1988, 225; Luraghi Reference Luraghi2002, 56).

Dedications of figurines and various objects bearing images of wild animals affirm the role of Limnatis as Mistress of Animals (potnia therôn), while bronze cymbals found in her sanctuaries allude to musical contests and choruses or even the goddess' orgiastic rituals.Footnote 92 Artemis was also worshipped as protectress of new mothers and children, a kourotrophos or a paidotrophos. Ornaments such as earrings, beads, pinsFootnote 93 and bronze mirrors, underline the piety as well as the strong presence of women that characterised the sanctuary. Young girls or their devout parents dedicated personal belongings such as mirrors, ornaments and toys, a ritual associated with the end of adolescence (Fränkel Reference Fränkel1876, 29; Bevan Reference Bevan1987, 17–18; Calame Reference Calame1997, 114–15).Footnote 94 The possible presence of young girls in ceremonial clothes and jewellery (ἐσθῆτι καὶ κόσμῳ) (Pausanias 4.4.3) should apparently be related to the processions, choruses, even rites of passage performed in the sanctuary (Brelich Reference Brelich1969, 30–1; Zunino Reference Zunino1997, 50–1; Polignac Reference Polignac and Kyriazopoulos2000, 92–4),Footnote 95 just as at the sanctuary of Artemis Limnatis at Laconian Boiai (Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 952; Calame Reference Calame1997, 148). On the other hand, the story of Spartan youths disguised as girls alludes to the cross-dressing of adolescents attested in rites of passage, an act typical of the transitional phase before entering adulthood (Brelich Reference Brelich1969, 30–1; Calame Reference Calame1997, 145–7). Agonistic contests superintended by the goddess herself were also incorporated into the ritual tradition of the Limnatis sanctuaries (Lo Monaco Reference Lo Monaco, Rizakis and Lepenioti2010, 319; see also Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 952).

Adult women facing gynaecological problems, or having undergone a hazardous labour, must also have visited the sanctuary, offering to the goddess pins, fibulae, garments, even shoes worn during their pregnancy and labour (Rose Reference Rose and Dawkins1929, 403; Polignac Reference Polignac and Kyriazopoulos2000, 92–4).Footnote 96 The role of Limnatis as protectress of pregnant women and young mothers is reflected in the cult of Panayia Kapsocherovoloussa at Volimnos; the Christian chapel is dedicated to the offering of the Holy Garment of the Virgin (timia esthēta), a narrative which reflects the offering of garments to Limnatis, suggesting continuity of cult.Footnote 97

EPILOGUE: BEHIND LIMNATIS' MIRROR

It is evident that Artemis Limnatis was worshipped at Volimnos continuously from the Geometric era down to the third century ad. Regardless of whether her sanctuary had been founded by the Spartiates or not,Footnote 98 it is likely to have become a meeting point for locals (Luraghi Reference Luraghi2002, 56–7 n. 67; Deshours Reference Deshours2006, 161–2; Koursoumis Reference Koursoumis2004–9, 318).Footnote 99

After 369 bc, the new Messenian polity was at pains to prove its hereditary rights to the land, contesting the Spartan refusal to acknowledge that the people of the new state were descendants of the ancient Messenians.Footnote 100 Therefore, it was a matter of utmost importance that ‘all aspects of the Messenian narrative and cultural record [should] undergo a metamorphosis’ (Alcock Reference Alcock1999, 337), in order to support their ethnic goals; a new ethnic history, containing narratives of Dorian genealogies, crucial events and incidents, the suicide of king Aristodemos and the exploits of the hero Aristomenes, and the ethnos' rebellions, as well as the story of its liberation, had to be recorded.Footnote 101 Old and new cults were established in the city centre, reinforcing Messenian claims concerning their origin. In the late fourth century/early third century bc the Asklepieion, at the heart of the new centre of the city, was erected to accommodate cults of ‘Messenian’ gods and heroes, while the ethnos' Dorian genealogy was depicted in the paintings of the temple of Messene (Pausanias 4.31.11–12). From the mid-third century bc writers began to document Messenian history: Myron of Priene wrote a historical account of the First Messenian War, while a few decades later the Cretan poet Rhianus composed an epos on the Second Messenian War in Andania, describing the borders of the Messenian land (Pausanias 4.6.1–6; Luraghi Reference Luraghi2008, 286). Apparently, the new polity's propaganda regarding its ancestral rights to the region incorporated narratives and monuments that were thought to reflect the past, especially when associated with areas over which dominance remained disputed. Pausanias' (4.31.3) pro-Messenian argument that Limnai was related to the Messenian, yet philo-Laconian, mountainous kome of Kalamai indicates that the conflict between the two neighbouring ethne, even as late as the second century ad, was still unresolved.

Contemporary and consistent with the above developments was the establishment of the Artemis Limnatis cult on the western slope of Mount Ithome, within the city walls. In a small shrine facing the city, next to a spring, a small temple of Ionic or Corinthian order was erected sometime in the third century bc; the cult statue of the goddess, depicting her as a hunter, a kynegetis, stood inside the cella (Le Bas Reference Le Bas1844, 422–5; Reinach Reference Reinach1888, 134–8, pls. 1–4; Themelis Reference Themelis2004, 143–54; Müth Reference Müth2007, 211–16, fig. 112). Inscriptions related to the sanctuary record the epithet of the goddess (Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, nos. 1442, 1458; Themelis Reference Themelis1988a, 45–6; Reference Themelis1988b, 72; Brulotte Reference Brulotte1994, 255–7; Müth Reference Müth2007, 213–15), who was worshipped ‘in the marshes’, overseeing the manumission of slaves as a guardian of social boundaries (Kolbe Reference Kolbe1913, no. 1470). The foundation of a Limnatis temple on the slope of the Messenian ‘holy’ mountain should be perceived as an explicit reference to the Messenian claims over the Taygetos sanctuary, reflecting the fact that by that time the Dentheliatis region was or had been under Spartan rule (Roebuck Reference Roebuck1941, 62; Magnetto Reference Magnetto1997, 294 n. 15; Luraghi Reference Luraghi2008, 18–19, 256–7 n. 27, 287).

Although the historical importance of the Limnatis sanctuary in terms of military and political rule over central Taygetos is well documented and persuasively recorded in literary sources, the material evidence from Volimnos remains scanty and incoherent. Various votive offerings, remains of architectural structures and epigraphic material documenting the presence of high-ranking priests and wealthy benefactors are just reflections of the history of a sacred area of great importance and reputation. As we still know nothing about the precise find spots of the objects, we may entertain all manner of conjecture about the exact site of the sanctuary, and the size of its temenos and its temple respectively. Nothing more definite can be maintained, short of excavation on the terrace and an extensive survey along the valley and the western slopes of the mountain.