I. Introduction

Especially since the end of WWII, states have created numerous International Organisations (IO), covering a broad array of policy areas and attracting numerous member states. In these institutionalised negotiation arenas, national diplomats create binding or non-binding international rules and norms (Kelsen Reference Kelsen1966; Alvarez Reference Alvarez2005). To this end, they articulate national positions and exchange legal, factual, normative and political arguments for and against text proposals or changes (Menkel-Meadow Reference Menkel-Meadow1983; Kratochwil Reference Kratochwil1989; Beaulac Reference Beaulac2004; Koskenniemi Reference Koskenniemi2006; Levi Reference Levi2013). Diplomatic deliberation, as the exchange and contestation of positions, claims, demands and reasons, is not just a symbolic exercise taking place during the making of international hard or soft law, since the power of the spoken word can influence interaction outcomes, and possibly also the quality, legitimacy and efficiency of governance beyond the nation state (Manin Reference Manin1987; Fishkin Reference Fishkin and Simon2002; Cohen Reference Cohen, Matravers and Pike2003; Thompson Reference Thompson2008; Cohen Reference Cohen2012; Wiener Reference Wiener2014).

The institutional design of IOs is spelled out in their primary law, which can encompass founding treaties, treaty changes, annexes and protocols. The body of IO primary law serves as their ‘constitution’ (Dunoff Reference Dunoff2006; Dunoff and Trachtman Reference Dunoff and Trachtman2009). Although ‘the optimal design of international institutions to confront 21st century challenges is an increasingly urgent question’ (Abbott and Gartner Reference Abbott and Gartner2012), we know very little about how and why institutional designs of IOs differ in facilitating deliberation between state actors and to what effect.

Within the ‘deliberative turn’, scholars from political science, political philosophy and sociology focused on the phenomenon of deliberation (Hamlin and Pettit Reference Hamlin and Pettit1989; Schneiderhan and Khan Reference Schneiderhan and Khan2008; Gutmann and Thompson Reference Gutmann and Thompson2009; Dryzek Reference Dryzek2012; Ryfe Reference Ryfe2007). While deliberation is broadly understood as the communicative exchange of claims and reasons between actors, different scholars define deliberation in different manners. While some focus on the speech acts exchanged (position or claim backed up by factual, normative, legal, scientific or political reason) (Landwehr and Holzinger Reference Landwehr and Holzinger2010), others stress that deliberation is a reflexive process that requires ‘reason-giving and listening’ (Bächtiger and Parkinson Reference Bächtiger and Parkinson2019) Footnote 1 and that for deliberation to take place it is essential that actors are open not only to persuade others but also to become persuaded in the wake of the better argument themselves (Habermas Reference Habermas1995a, Reference Habermas1995b). We follow a broad definition of deliberation that makes no ontological assumptions about the actors’ degree of reflexivity or the endogeneity of their interests and preferences. Instead, we define deliberation as the exchange and contestation of ideas on the basis of national positions that actors justify with legal, factual, normative, causal, scientific, ethical or values-based reasons. Footnote 2

The ‘deliberative turn’ gave rise to studies on how deliberative elements within democracies, such as deliberative assemblies or online deliberation, influence the quality, efficiency and legitimacy of governance (Goodin and Dryzek Reference Goodin and Dryzek2006; Shapiro Reference Shapiro2003; Goodin Reference Goodin2008). Compared to deliberation within states, we know less about deliberation within IOs. Individual case studies shed light on the usage or arguments by diplomats and study how it translates into negotiation success (Risse Reference Risse2000; Deitelhoff and Müller Reference Deitelhoff and Müller2005; Panke Reference Panke2010; Reinhard, Biesenbender and Holzinger Reference Reinhard, Biesenbender and Holzinger2014). Although many scholars point out that institutional design matters and can influence deliberative practices (Habermas Reference Habermas1995a; Joerges and Neyer Reference Joerges and Neyer1997; Panke Reference Panke2006; Deitelhoff Reference Deitelhoff2009; Landwehr and Holzinger Reference Landwehr and Holzinger2010; Risse and Kleine Reference Risse and Kleine2010; Risse Reference Risse2000; Deitelhoff and Müller Reference Deitelhoff and Müller2005; Panke Reference Panke2010, ; Reinhard, Biesenbender and Holzinger Reference Reinhard, Biesenbender and Holzinger2014), no one has systematically examined in a comparative manner to which extent and why IO constitutions differ when it comes to inducing diplomatic deliberation. Additionally, no one has studied the extent to which state actors deliberate over a large number of IOs, and their corresponding effects. These gaps are surprising for several reasons. First, IO institutional design essentially regulates how diplomats as the core actors with voting rights interact in order to create negotiation outcomes. For example, rules setting a maximum number of pro and con arguments per proposal or rules restricting the duration of a speaker’s time or the discussions in general seek to delimit the extent of diplomatic deliberation and speed up negotiations. At the same time, IO institutional design features, such as provisions allowing for the right of reply or rules on making proposals orally rather than in writing only and do so without secondment, seek to induce diplomatic deliberation as the exchange and contestation of ideas on the basis of national positions and legal, factual, normative, causal, scientific, ethical or values-based reasons.

While diplomatic deliberation reduces the speed of decision-making, deliberation can increase the legitimacy and possibly also the quality of outcomes (Manin Reference Manin1987; Hamlin and Pettit Reference Hamlin and Pettit1989; Franck Reference Franck1990; Steffek Reference Steffek2000; Biegoń Reference Biegoń2016; Eckl Reference Eckl2017). Diplomatic deliberation can be time-intensive and therefore reduces the effectiveness of decision-making – especially as the IO in question has many member states. At the same time, diplomatic deliberation can bring about a principled and well-justified outcome that reflects not simply the lowest common denominator of the actors’ initial positions. IOs have a demand for legitimacy (Grigorescu Reference Grigorescu2015; Dingwerth et al. Reference Dingwerth, Witt, Lehmann, Reichel, Weise, Dingwerth, Witt, Lehmann, Reichel and Weise2019), not only since this increases the chances that state actors choose them as arenas under conditions of regime complexity in the first place and use them in order to pursue ambiguous policy goals, but also because this increases state compliance with IO outcomes afterwards (Reference Tallberg and ZürnTallberg and Zürn forthcoming). Since legitimacy is the acceptance of the exercise of authority as appropriate by the governed (Reference Tallberg and ZürnTallberg and Zürn forthcoming), how IOs are institutionally designed can matter (Grigorescu Reference Grigorescu2015; Lenz and Viola Reference Lenz and Viola2017). IOs that are designed to induce high levels of diplomatic deliberation have greater potential to produce high-quality decisions thereby grounding the final IO outcomes in sound argumentation rather than merely reflecting the interest of a few powerful actors. This is important as the perceptions of citizens of an IO’s procedural and performance quality impacts its legitimacy (Reference Anderson, Bernauer and KachiAnderson, Bernauer and Kachi forthcoming).

In fact, many institutional design rules of IOs tend to either foster or restrict diplomatic deliberation, in order to create a balance between the speed of negotiations as well as the legitimacy and/or quality of negotiation outcomes. Yet, we do not know how different IOs balance these competing aims in their institutional designs. Second, several studies have analysed the access of organised civil society actors, such as non-governmental organisations, to decision makers in IOs as well as the deliberative quality effects of civil society access (Bexell, Tallberg and Uhlin Reference Bexell, Tallberg and Uhlin2010; Nanz and Steffek Reference Nanz and Steffek2004, Reference Nanz and Steffek2005; Kuyper Reference Kuyper2014; Tallberg et al. Reference Tallberg, Sommerer, Squatrito and Jönsson2013). While we know a lot about IO institutional design and its openness for non-state actors, we do not know how IOs vary in the extent to which their institutional design facilitates deliberation between the core actors: states. This is all the more surprising as multilateral negotiations within IOs are an essential part of international relations in the twenty-first century, ranging from climate change and other environmental topics to trade and international security.

In order to fill gaps in our current knowledge, this article addresses the following research question: To what extent do IOs incorporate deliberative institutional design features and how can we explain variation in the extent to which institutional design seeks to foster diplomatic deliberation between IOs?

We answer this question in the following steps. Section II introduces the dataset, which captures how strongly IOs are institutionally designed to foster or delimit diplomatic deliberation. We create a diplomatic deliberative design index (DDDI) and examine how IOs differ in this respect (Section III). Most notably there is considerable variation between IOs. While some, such as the Conferencia de Autoridades Audiovisuales y Cinematográficas de Iberoamérica (CAACI), the International Office of Epizootics (OIE), and the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) hardly seek to foster deliberation, the Conference of Disarmament (CD), the International Commission for the Protection of Mosel and Saar (IKSMS) and the Central American Integration System (SICA) are located at the other end of the continuum, while IOs such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) or the International Monetary Fund (IMF) are in between. In order to account for this variation, section IV draws on functionalism, rational choice institutionalism and liberal approaches and develops hypotheses. Section V examines the empirical plausibility of the hypotheses based on quantitative methods. This reveals that IOs which focus on high politics issues have institutional designs which are significantly geared towards fostering diplomatic deliberation. In addition, IOs with a regional focus and IOs that are small in size tend to also feature constitutions with features geared towards diplomatic deliberation.

II. Measuring the diplomatic deliberative quality of IO institutional design

This section discusses the construction of the dataset starting with the sampling of IOs, followed by the introduction of the selected institutional design criteria, the construction of the deliberative institutional design index and the coding-related decisions.

International Organisations are defined as institutionalised forms of cooperation between three or more states (Hurd Reference Hurd2011).We further specified this definition through the following criteria: First, we only include IOs whose purpose is to create or reinforce international norms and rules, while all IOs that have no authority to engage in such standard-setting activities are excluded (e.g. commercial purpose organisations such as banks, advisory bodies like think tanks, scientific study groups). Second, IOs must be composed of member states and in exceptional cases regional organisations, whereas organisations including firms, private persons etc. are excluded. Third, an IO must still be in operation in 2016 rather than just existing on paper, which we captured by the existence of an updated homepage. The last criterion allows to exclude so-called ‘Zombie-IOs’ which only exist on paper but are no longer in operation or in use (Gray Reference Gray2018). The existence of an updated homepage is the prerequisite to access and obtain the necessary documentation to comprehensively map IO institutional design (see below). Footnote 3

The basis for the selection of IOs as defined above is the Correlates of War database (Pevehouse, Nordstrom and Warnke Reference Pevehouse, Nordstrom and Warnke2004) as well as the Yearbook of International Organizations, Footnote 4 because they together cover the universe of IOs, while each database alone omits some cases. Footnote 5 Out of this universe of IOs we selected a representative subsample of 114 IOs, in which states and state-based actors (e.g. the European Union) constitute the members, Footnote 6 which are still in operation in 2016, have a website, and provide primary law documents and information about rules of procedures. The sample includes IOs that vary with regard to their size, age, policy field, regional vs. global reach and proportional representation of world regions concerning the regional IOs.

For all the IOs included in the sample, we coded their diplomatic deliberative institutional design, which structured the interaction of state actors in the main legislative arena and if present, the respective subsidiary bodies of the IOs. Footnote 7 Our main focus is on the deliberation of state actors in IOs rather than on IO bureaucrats or observers as member states are the constituents of IOs as thus the main actors responsible for dynamics and outcomes of interaction. Yet, since in some IOs non-state actors (NGOs), associates and state or non-state observes can in some instances formally, in others informally also take the floor, we also take them into account when coding the deliberative nature of IO institutional design (see framework conditions below).

For the coding, we used two sources: IO constitutions as primary law (e.g. founding treaties and treaty changes, protocols, annexes) as well as the procedural rules (e.g. terms of references, rules of procedures). For each IO we captured the extent to which their institutional design seeks to induce or hamper diplomatic deliberation for one year. We decided to collect all data for the year 2016 as this is the year for which we were able to systematically gather all treaty documents (founding treaties and subsequent changes) and all rules of procedures. We opted against using the founding year of an IO as reference point since this would not allow to systematically include rules of procedure into the coding and since this would neglect that in some IOs treaty changes took place over time and adjusted the institutional design. Furthermore, coding the IOs for their respective founding years only would make comparisons difficult, as some were created in the aftermath of WWII or even earlier (such as the International Labor Organization (ILO) created in 1919), while others are considerably younger (such as the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) created in 2008).

Table 1. List of IOs

Drawing on the literature on deliberation (Bächtiger and Hangartner Reference Bächtiger and Hangartner2010; Cohen Reference Cohen, Matravers and Pike2003; Deitelhoff Reference Deitelhoff2006; Habermas Reference Habermas1995a; Landwehr and Holzinger Reference Landwehr and Holzinger2010), we developed a detailed coding scheme. We differentiate between three stages of IO policy cycles namely agenda setting, negotiation, and final decision-making and identify several elements related to deliberation for each of the stages (for an overview compare Table A1, Appendix). Every element was captured by one or several indicators. The first stage, the agenda-setting stage, starts with the drafting of agenda items and ends with a finalised agenda (Panke Reference Panke2013). The second stage, the negotiation stage, starts once the actors have a meeting agenda and ends after substantive text changes are finalised. The third stage, the voting stage starts after the main negotiations are concluded and incorporates the debates around and after the formal passing of a negotiation outcome took place (Panke Reference Panke2013).

In the agenda-setting stage, we distinguish three different elements, namely calling a meeting, right to agenda setting, possibilities to change the agenda. Examples for rules increasing the possibility of diplomatic deliberation in the agenda-setting stage include not limiting the number of speakers allowed to discuss the pros and cons of whether an item should be included on the negotiation agenda and not putting a time limit on the discussion of the agenda. In the negotiation stage, we distinguish between four elements that can facilitate or hinder deliberation between diplomats (dynamics of debate, Chair competences to regulate, making proposals, and interruption of debate). For instance, not limiting the number of times a state may speak up during a debate and provisions to give way, and a right of reply, provisions allowing for speakers to be interrupted by other states, making proposals orally instead of putting them in writing are all conducive to diplomatic deliberation. Examples of rules limiting diplomatic deliberation in the negotiation stage include granting chairs the competence to interrupt speakers and shorten their speeches, requiring secondments for proposals or amendments during negotiations or not allowing or severely limiting the possibility for states to reintroduce formerly withdrawn proposals or amendments. The decision-making stage encompasses two elements related to the quorum to open decision-taking and high thresholds for decision taking. In addition to the policy cycle, we also coded three institutional design elements on framework conditions, such as whether an IO provides translation, is open to advisors and experts accompanying the diplomats or allows other actors (NGOs etc.) access to the meetings (see Table A1 in the Appendix).

Each of the 34 indicators was formulated as a question (cf. Table A1), which was answered by checking the primary law and rules of procedure of every IO in turn. Since most indicators require to identify the respective context (agenda setting, negotiation, and final decision making as well as framework conditions), we did not compile a list of buzzwords to code in an automated fashion (e.g. with Atlas.ti or MAXQDA) Footnote 8 but hand-coded all materials. In order to achieve inter-coder reliability, all coding decisions were double-checked by a second person.

The DDDI indicators are coded with –1 if they are designed to hinder deliberation between diplomats and with +1 if they are geared towards inducing diplomatic deliberation. For instance, in the agenda-setting stage, deliberation is more likely to take place if the number of IO members who can set the agenda increases. Thus we code the possibility of member states or institutional actors to set the agenda with +1, whereas in case only specific institutional actor (e.g. chairs or secretariats) can set the agenda, the indicator was coded –1.

The coding resulted in raw data on the extent to which the 34 indicators are geared to induce or prevent deliberation between diplomats. For the construction of the diplomatic deliberative design index (DDDI), we aggregated the 34 indicators into a total of nine institutional design elements alongside the policy cycle and three additional design items on framework conditions (cf. Table A1). We opted for the aggregation of the indicators into these elements to avoid duplicating similar and logically connected provisions which would have skewed the DDDI. For instance, in the negotiation stage, several indicators relate to the making of proposals. On the one hand, we examine whether proposals could be made by the delegates, but there are also more detailed provisions on the timing, support for, withdrawal and reconsideration of proposals. In general, having the possibility to make proposals, do so without the support of additional states, and the potential to obtain exceptions concerning the timing of proposals can all induce diplomatic deliberations, as it can broaden and expand debates. Yet the latter indicators can logically not exist without the possibility to make proposals in the first place (first indicator). Thus, counting each indicator separately for the DDDI would have inflated the index with respect to this event in the policymaking cycle. Accordingly, we combined all these indicators into one element ‘making proposals’. As the subsequent indicators rather qualify the operation of the first (core indicator), the first is weighted higher than the other two. For all such interlinked indicators, we weighted the core indicator by 0.5 and all qualifying indicators taken together are also assigned a weight of 0.5 (cf. Table A1).

We constructed the DDDI by forming the average of the 12 elements (cf. Table A1). For all organisations we did this process for the main legislative body first. For approximately half of the IOs, deliberation does not only take place in the main legislative body, but also in subsidiary bodies such as working groups, committees, specialised commissions etc. For these IOs we additionally applied the coding scheme to the rules of procedure of the subsidiary bodies. We calculated the final DDDI value for these IOs by giving equal weight to the value for the main legislative weight and the average of the values for all subsidiary bodies. As each indicator can take the values of 1 and –1, the values of the final index are also situated within this range. Thus, an IO’s institutional design is most strongly inducing deliberation between diplomats if its DDDI approximates +1, and most strongly preventing diplomatic deliberation if its DDDI approximates –1.

III. A descriptive analysis of the diplomatic deliberative design index

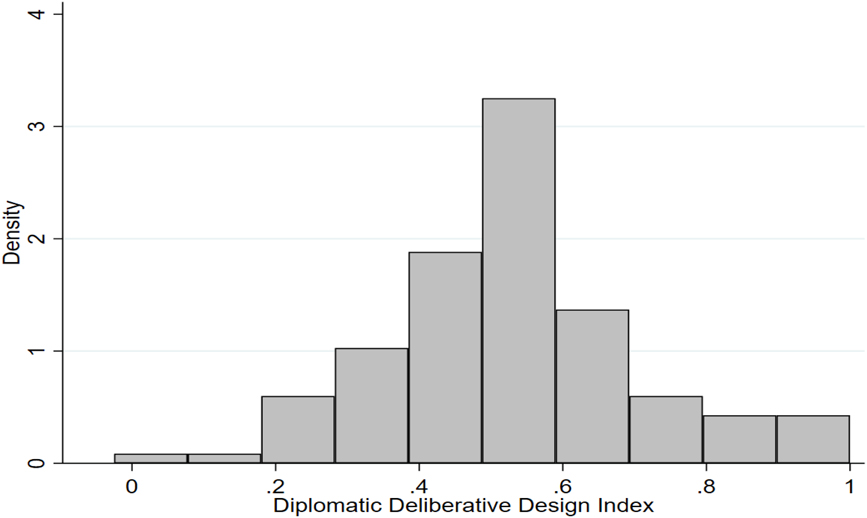

How do the 114 IOs from our sample score on the diplomatic deliberative design index? When we take a look at the empirical distribution, we can see that most IOs seem to induce rather than hamper deliberation. The average value of the DDDI is 0.526 implying that most IOs have more items, which are designed to facilitate deliberation than restrictions of the same. As Figure 1 illustrates the DDDI is almost normally distributed amongst the 114 IOs. Empirically the DDDI ranges between –0.025 and 1.

Figure 1: Empirical distribution of the DDDI

Only one organisation is institutionally designed in a manner strongly limiting the exchanges between state delegates: The Latin American Conferencia de Autoridades Audiovisuales y Cinematográficas de Iberoamérica (CAACI) (cf. Table A1, Appendix). Most notably, states are not involved in the agenda setting; it is possible that debates are closed in the negotiation stage without a prior discussion on that decision; and finally in the decision-making stage majority rule applies.

At the other end of the spectrum, the institutional design of the International Commission for the Protection of Mosel and Saar (IKSMS) and the Central American Integration System (SICA) contains only items facilitating deliberation. They both score 1. The institutional design of IKSMS and SICA both seek to foster deliberation by explicitly allowing for calling of an exceptional meeting in the agenda-setting stage, and both focus on consensus decision-making rules with a one-state one-vote specification in the decision-making stage, and the general IO institutional design allows for the access of non-state and other actors. In addition, IKSMS provides for the translation of documents and speeches.

In between are IOs such as the United Nations Security Council (UNSC, 0.557) or the World Trade Organization (WTO, 0.523). For instance, in the UNSC and the WTO states are the agenda setters. In addition, the UNSC and the WTO also fosters deliberation through dynamic debates by allowing states to make proposals and amendments and by giving chairs the competency to accord the right to speak to participants in the negotiation stage; in the decision-making states both IOs include quorums and one-state, one-vote rules. Moreover, the UNSC and the WTO’s institutional set-up is designed to allow for transparency of meetings and both have provision that would allow for the access of external actors (but no speaking rights). The UNSC and the WTO also differ in some respects. For instance, only the institutional design of the WTO fosters deliberation by allowing states to flexibly change the agenda and explicitly allow for discussions amongst states to this effect; during the negotiations states have the right of reply and there is a discussion before debates can get closed. In the decision-making stage, consensus rule applies. Also, according to the WTO’s general provisions, delegations can bring advisors. In the UNSC, there are likewise institutional design elements allowing for diplomatic deliberation that are not present in the WTO. Most notably, the UNSC fosters deliberation by explicitly allowing for states calling for exceptional meetings in the agenda-setting stage, by flexibly adjusting the order of speakers, by allowing states to make proposals or amendments without secondments in the negotiation stage, and by providing opportunities for reintroducing formerly failed proposals. In general, the UNSC allows for the access of other actors with speaking rights and translations, both of which can also foster deliberation. This illustrates that there is not the one blueprint for the institutional design of IOs when it comes to regulating the extent of diplomatic deliberation. Instead, IOs vary considerably.

IV. Theorising deliberation and IO institutional design choices

There is a vast literature on the prevalence of deliberation and contestation in democratic states (e.g. Chambers Reference Chambers2003; Fishkin and Luskin Reference Fishkin and Luskin2005; Goodin and Dryzek Reference Goodin and Dryzek2006; Hafer and Landa Reference Hafer and Landa2007; Goodin Reference Goodin2008; Thompson Reference Thompson2008; Dryzek Reference Dryzek2012), the legal realm (e.g. Alexy Reference Alexy1983; Layman and Saxon Reference Layman and Saxon1998; Ferejohn and Pasquino Reference Ferejohn, Pasquino and Sadurski2002; Zurn Reference Zurn2007; Pickerill Reference Pickerill2004; Kim Reference Kim2009; Lillich and White Reference Lillich and Edward White1976) or in the societal context (Hajer and Wagenaar Reference Hajer and Wagenaar2003; O’Flynn Reference O’Flynn2006; Ryfe Reference Ryfe2007; Schneiderhan and Khan Reference Schneiderhan and Khan2008). Amid more recent ‘deliberative turn’ literature, the scope of actors was further broadened in order to also study deliberation within and between companies and consumers (Doubleday Reference Doubleday2004; Palazzo and Scherer Reference Palazzo and Georg Scherer2006; Warner Reference Warner2008; Guo and Zhang Reference Guo and Zhang2012; Singer and Ron Reference Singer and Amit2018), between parliamentarians in national legislative arenas (Steiner Reference Steiner2004; Bächtiger et al. Reference Bächtiger, Spörndli, Steenbergen and Steiner2005; Bara, Weale and Bicquelet Reference Bara, Weale and Bicquelet2007; Bächtiger and Hangartner Reference Bächtiger and Hangartner2010) as well as the role of non-governmental organisations in deliberative processes beyond the nation state (Steenbergen et al. Reference Steenbergen, Bächtiger, Spörndli and Steiner2003; Nanz and Steffek Reference Nanz and Steffek2005; Brakman Reiser and Kelly Reference Brakman Reiser and Kelly2011; Niemetz Reference Niemetz2014; Tallberg et al. Reference Tallberg, Sommerer, Squatrito and Jönsson2013). Moreover, a body of deliberation scholarship evolved which focused on state behaviour on the international level (Johnstone Reference Johnstone2003; Naurin Reference Naurin2009; Landwehr and Holzinger Reference Landwehr and Holzinger2010; Risse and Kleine Reference Risse and Kleine2010; Risse Reference Risse1999; Risse Reference Risse2000; Reinhard, Biesenbender and Holzinger Reference Reinhard, Biesenbender and Holzinger2014; Deitelhoff Reference Deitelhoff2009; Wiener Reference Wiener2014; Müller Reference Müller2004; Risse Reference Risse2000). Similar to the first-generation deliberation researchers, deliberative turn scholarship usually draws on case studies of selected interactions or negotiations or uses simulations to empirically examine exchanges between actors (e.g. Nanz and Steffek Reference Nanz and Steffek2005; Gehring and Kerler Reference Gehring and Kerler2008; Landwehr and Holzinger Reference Landwehr and Holzinger2010; Risse and Kleine Reference Risse and Kleine2010; Reinhard, Biesenbender and Holzinger Reference Reinhard, Biesenbender and Holzinger2014). This body of work illustrates that deliberation is a widespread phenomenon, taking place in the political, societal, legal realms and to some extent also the economic sphere. In addition, deliberation researchers also examine conditions under which deliberation is most likely to unfold. In this regard, deliberation between national diplomats – although the backbone of international relations – and especially the role of different institutional design features that seek to foster diplomatic deliberation in IO agenda-setting, negotiations and decision-taking, such as rules for speaking rights or the number of interventions allowed, is surprisingly seldom under scrutiny. This is surprising since much of the diplomatic business in IOs is about exchanging claims and simultaneously providing legal, factual, scientific or normative reasons to support one’s national position (Johnstone Reference Johnstone2003; Müller Reference Müller2004; Risse Reference Risse2004). Hence, instead of being empirically rare, diplomatic deliberation is a widespread feature of multilateral negotiations (e.g. Reinhard, Biesenbender and Holzinger Reference Reinhard, Biesenbender and Holzinger2014; Risse and Kleine Reference Risse and Kleine2010; Landwehr and Holzinger Reference Landwehr and Holzinger2010; Nanz and Steffek Reference Nanz and Steffek2005; Gehring and Kerler Reference Gehring and Kerler2008). Yet, up to now, there are no studies that systematically examine differences in IO institutional diplomatic deliberative design. Thus, there are no specific IO deliberative design theories that this article can draw on. Hence, in order to account for the empirical variation in the IOs’ institutional designs, we draw on functionalism, rational design approaches, and liberal approaches and specify hypotheses to account for between-IO variation.

According to functionalism, political systems are designed to perform specified tasks, on the basis of which ‘form follows function’ (Mitrany Reference Mitrany1943; Haas Reference Haas1964; Gregor Reference Gregor1968). Once actors have identified what a specific political system should do, they select those institutional rules most suited to ensure smooth and effective operation of the system (Lowi Reference Lowi1963: 581–2). Thus, IOs’ core function is to facilitate state–state cooperation in order to solve real world problems. Accordingly, IO institutional design should ensure that conflicts between state parties can be resolved quickly or circumvented instead of culminating in standstills (Mitrany Reference Mitrany1943; Haas Reference Haas1964). Consequently, functionalism expects a limited number of deliberative elements in IOs in general. This allows states to swiftly address the problems that they have decided to tackle, rather than facing situations in which the development of international rules and norms is highly deliberative but very time-intensive. This general expectation can be qualified in two ways: The more member states an IO has, the more time-intensive negotiations take if all members voice their positions. Thus, functionalism expects that the institutional design of larger IOs delimits diplomatic deliberation more strongly than the institutional design of smaller IOs. The functional operating of IOs can also be influenced by the amount of policy issues on the agenda. IOs with broad policy scopes are responsible for many different topics and are therefore likely to place a high workload on the negotiating actors. Given a broad policy scope and a corresponding high workload, an institutional design with lots of deliberative elements would be dysfunctional, as this would increase the time for decision-making enormously.

Accordingly, hypothesis 1a states: IOs with a higher number of member states should have fewer deliberative design elements.

Hypothesis 1b focuses on policy aspects: IOs with a broad scope of policy mandates should have fewer deliberative design elements.

On the other hand, swift decision-making is not the only criterion for a rational institutional design of IOs (Goodin Reference Goodin1995; Koremenos, Lipson and Snidal Reference Koremenos, Lipson and Duncan2001; Panke Reference Panke2016). States design IOs not only to allow for the efficient making of decisions, but also seek to ensure that the outcomes reflect the normative and legal convictions of the member states and address the underlying problems (Manin Reference Manin1987; Müller Reference Müller2004; Schneiderhan and Khan Reference Schneiderhan and Khan2008; Risse and Kleine Reference Risse and Kleine2010; Eckl Reference Eckl2017). To pursue this aim, institutions include rules fostering diplomatic deliberation. The amount of time an IO allows for deliberation is likely to depend on the nature of the issue at hand and the actors involved in the discussions.

International Organisations can deal with a multitude of issues ranging from highly detailed technical questions to crucial security issues. The saliency of the issue at hand plays an important role: IOs which cover policy areas of high political salience, such as security and economic issues, should generally allow for more deliberation, in order to grant encompassing and sufficient debate of fundamental questions (see further Johnstone Reference Johnstone2003). In contrast, IOs which are active in low politics fields should have less deliberative institutional designs. Also a second aspect might be of importance: the extent to which IOs might be confronted with internal policy conflicts is likely to vary with the expected heterogeneity of actor interests at stake in the IO (Cox and Jacobson et al. Reference Cox and Jacobson1973; Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Lake, Nielson, Tierney, Hawkins, Lake, Nielson and Tierney2006). Within regional IOs it is more likely that problems affect member states in a similar way, which could reduce the number of cleavages the actors have to deal with in the respective IOs. Compared to regional IOs, the actors in global IO come from more diverse contexts. Thus, global IOs might face a higher risk of policy conflicts than regional IOs, and their respective institutional designs should be less deliberative in nature.

Hypothesis 2a states: IOs’ institutional design is more deliberative in nature, if the IO in question covers high politics.

Hypothesis 2b expects: IOs with a global membership should have fewer deliberative design elements.

In addition to these two theories, we incorporate liberal approaches. Liberal theories open the ‘black box’ of intra-state decision-making and shed light on how dynamics emanating from the domestic realm can influence state foreign policy preferences and behavioural options (Doyle Reference Doyle1983; Putnam Reference Putnam1988; Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik1993; Panke and Risse Reference Panke, Risse, Dunne, Kurki and Smith2007; Panke and Henneberg Reference Panke and Henneberg2017). Some liberal approaches theorise that socialisation effects take place across levels, according to which domestic modes of actions and experiences can influence the behaviour of actors on the international stage (for an overview Panke and Risse Reference Panke, Risse, Dunne, Kurki and Smith2007). In democratic countries deliberation is a fundamental part of the political decision-making process (Grigorescu Reference Grigorescu2015; Biegoń Reference Biegoń2016), for instance parliamentarians discuss legislative proposals, political parties engage in controversial discourses etc. In contrast, authoritarian countries often lack a similarly established culture of debate. Following liberal approaches, we would expect that these patterns should be mirrored at the international stage: IOs with a dominantly democratic membership should provide more opportunities for deliberation than IOs which mostly consist of autocratic states.

Grounded on these considerations hypothesis 3 states: IOs with a dominantly democratic membership should be more likely to foster deliberation in their institutional design than IOs with an autocratic membership.

V. Empirical analysis and discussion of findings

The following section describes our operationalisation of the independent variables and explains our model specification. On this basis, we put our hypotheses to an empirical plausibility probe on the basis of quantitative methods. The diplomatic deliberative design index DDDI captures the extent to which IOs are designed to foster deliberation between diplomats in 2016.

The first independent variable captures the number of member states of an IO (hypothesis 1a). We counted the number of member states with full membership rights in 2016 based on the official IO websites. Associated members, observer states and suspended states were excluded, as these actors do not have the same rights in all IOs (in some IOs observers are by nature silent, in others they may informally speak and in yet others they can take the floor after all full members have spoken). The count variable ‘number of member states’ is divided by 10, thus a unit change of the variable corresponds to 10 member states the regression table. Hypothesis 1b captures the scope of policy competencies of an IO, which we measure through the number of policy fields in which it has a mandate based on its primary law (founding treaty and treaty changes). We coded IO competencies in the following eight fields: economic/finance/labour cooperation; security/ disarmament cooperation; health/safety issues; environment/nature; science/technology/ transport; culture; human rights; other issues. This data has been obtained from the official IO websites. The independent variable of hypothesis 2a specifies that high politics should lead to a more deliberative institutional design. Out of the policy fields listed above, we constructed a binary variable: the areas of economic/finance/labour cooperation and security/disarmament cooperation were coded as high politics (1) because these fields concern core interests of states. In contrast, the fields of health/safety issues; environment/nature; science/technology/transport; culture; human rights and other issues were coded as low politics (0). The independent variable of hypothesis 2b captures whether an IO is global or regional in nature. Based on the information in the IO treaties, we coded all IOs in which state membership is based on geographical proximity with 0, whereas all IOs open to countries worldwide were coded with 1. Hypothesis 3 states that IOs with democratic membership should be more likely to foster deliberation. We calculated the level of democracy within an IO by taking the average of the Polity IV values of the member states for 2016.

Subsequently, we examine the plausibility of the hypotheses with statistical methods. Our dependent variable, the diplomatic deliberative design index (DDDI) is a continuous and approximately normally distributed variable. We use an OLS regression model. The number of observations in our sample is only 114 and thus comparatively low, which requires special caution in model specification and interpretation of the results. Before building the multivariate models, we checked for multicollinearity between the independent variables in order to avoid using highly correlated independent variables in the same model. The results of the statistical analysis are shown in Table 2 and support some, but not all theoretical expectations. Footnote 9

Table 2. Regressions on the DDDI

Standard error with *0.10,** p<0.05,** p<0.01

A high number of IO member states robustly reduces the deliberativeness of institutional rules (models 1 and 2, Table 2). Thus, there is support for the first functionalist hypothesis, according to which larger IOs with high numbers of member states seek to delimit opportunities for diplomatic deliberation in order to avoid lengthy discussions if all actors would take the floor whenever they have the opportunity to do so and corresponding inefficient IO decision-making. In contrast, smaller IOs with fewer member states can afford highly deliberative institutional designs, as diplomatic deliberation is more likely to be limited in practice if the number of diplomats that can make use of their speaking rights is lower. To illustrate this, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) as one of the largest organisations with 167 member states has a score of 0.3375, whereas the comparatively small Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) (5 member states) has a DDDI value of 0.900.

The second functionalist expectation does not find empirical support: The policy scope of IOs shows a robustly positive effect, but is not significant in any of the models (models 1 and 3 in Table 2). Thus, it is not the case that IOs with a broad policy scope has fewer deliberative design elements. Many different policy mandates do not increase the workload on the IO negotiation table and the corresponding amount of diplomatic deliberation to an extent calling for constitutional limitations of deliberative opportunities. Thus, organisations with equally broad policy coverage such as the OAS (0.568) and the AU (0.245) differ considerably, while IOs specialising in one specific policy area, such as the International Office of Epizootics (OIE, 0.172) or the European Organisation for the Safety of Air Navigation (EUROCONTROL, 0.833) also feature considerably different scores. Taken together, hypothesis 1b needs to be rejected.

Hypothesis 2a is based on rationalist institutionalist design approaches and expects that IOs dealing with the sensitive policy fields of security and economy have many deliberative institutional features. In line with this, Table 2 demonstrates that IOs covering high politics have institutional designs that are more strongly geared towards diplomatic deliberation (models 2 and 4). This suggests that IOs allow for more deliberation and contestation amongst member state diplomats, the more sensitive the issues at stake and in need for broad agreement and legitimacy are. For instance, the CD covers high politics as it is primarily responsible for disarmament and also features a high DDDI (0.929), while the Human Rights Council (HRC) that focusses on human rights scores only with 0.272. In addition, there is tentative support for hypothesis 2b. Compared to regional IOs, global IOs seek to foster less diplomatic deliberation. This effect points into the expected direction in models 3 and 4. To illustrate this point, the institutional designs of regional IOs, such as the Comunidad Andina (CAN) and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) are highly deliberative in nature, while the designs of many global IOs, such as the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) and the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL), score considerably lower on the DDDI.

Concerning the final strand of literature, liberal theory, Table 2 illustrates that a dominantly democratic membership robustly increases the deliberativeness of an IO, as it is expected by hypothesis 3. However, the coefficients are not significant in any of the four models so that hypothesis 3 cannot be regarded as being supported by empirical evidence. In line with this, it is not surprising that IOs with identical DDDI scores (0.536) differ considerably with respect to the average regime type of their member states, the OECD (9.088) and the GCC (–8.833).

VI. Conclusions

Among other questions, political philosophy, in general, and global constitutionalism, in particular, explores what constitutes a good political order. While the former’s predominant focus has been on how to design a legitimate state in order to express values such as equality, freedom, justice, sovereignty or security (e.g. Hobbes Reference Hobbes1668; Rousseau Reference Rousseau1920; Locke and Laslett Reference Locke and Laslett1988; Tully and Skinner Reference Tully and Skinner1993; Kraut Reference Kraut2002), from early on some philosophers of the state were also interested in what constitutes a good international order (most prominently Kant Reference Kant and White Beck1795). In this context, political philosophers, political scientists and legal scholars examined authority beyond the nation state as well as legitimacy, justice, and fairness of global governance. Footnote 10 Not least since the number of IOs and the body of international law has considerably increased since the end of WWII, Footnote 11 institutional design scholarship evolved that examines the set-up of international organisations. Footnote 12

For instance, IO institutional design scholarship has studied the extent of legalisation of IOs. Footnote 13 This strand of research illustrates that formal institutional design of IOs influences state conduct, such as (non-)compliance, and points out that this has important implications for the prospects and effectiveness of cooperation beyond the nation state. Footnote 14 Another strand of IO institutional design research focuses on the openness of IO for non-state actors (Tallberg et al. Reference Tallberg, Sommerer, Squatrito and Jönsson2013). Most importantly, IO openness brings about promises for democratic global governance, although biased transnational access leads to an unequal representation of civil society interests in global governance arrangements (Tallberg et al. Reference Tallberg, Sommerer, Squatrito and Jönsson2013). A third prominent IO institutional design approach examines how and why IOs differ with respect to the pooling and delegation of authority (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2015; Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks, Lenz, Bezuijen, Ceka and Derderyan2017). This strand of institutional design scholarship sheds light on how IO set-up influences dynamics and outcomes of governance beyond the nation state (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2015; Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks, Lenz, Bezuijen, Ceka and Derderyan2017). Despite the current trend towards studying IO institutional design, not all features of potential importance for international negotiation dynamics and outcomes have already been under scrutiny. Although deliberation between state actors in IOs forms the core of global governance, Footnote 15 we know little about whether IOs differ in the extent to which they foster diplomatic deliberation. This is important since IOs – similar to states – need to balance two competing aims: On the one hand, they need to institutionally allow for swift policy-cycles, in which the actors can set the agenda, negotiate and pass outcomes in a time-efficient manner. On the other hand, they need to provide room for deliberation between actors in order to allow for policy outcomes that have a more realistic chance of being passed and been complied with. While the first aim suggests that institutional designs delimit opportunities for deliberation between actors, the second aim requires that institutional designs allow for diplomatic deliberation. In order to learn more about whether and how IOs balance these competing objectives, this article sheds light on the institutional design of IOs with respect to agenda setting, negotiation, and the decision-taking stage, and examines which institutional design features seek to foster deliberation between diplomats. In addition, this article examines why IOs’ institutional designs vary in the extent to which they seek to foster diplomatic deliberation.

The answers to the research question, ‘To what extent do IOs incorporate deliberative institutional design features and how can we explain variation in the extent to which institutional design seeks to foster diplomatic deliberation between IOs?’ are twofold. First, IOs considerably differ in the extent to which they are designed to induce diplomatic deliberation. While only one IO places much emphasis on swift policy-cycles and delimits diplomatic deliberation strongly (CAACI), other IOs made a different choice with respect to the two competing aims: Most notably, the institutional designs of IKSMS and SICA place strong emphasis on diplomatic deliberation and achieve the highest possible score on the DDDI. Most IOs balance both aims: speedy IO decision-making and room for diplomatic deliberation in the IO policy-cycle. For instance, IOs such as OECD, OAS and WTO, achieve median values on the DDDI. These findings suggest that it has not only been the case in the domestic arena that founding fathers drafted constitutions and wrote rules of procedures of parliamentary assemblies in a manner purposefully providing room for deliberation between the constituent actors whilst also ensuring that too much deliberation does not lead to a standstill (Bächtiger et al. Reference Bächtiger, Spörndli, Steenbergen and Steiner2005), but that similar consideration were also likely to be at play for the architects of today’s IOs.

Second, variation in the extent to which IOs are institutionally designed to foster deliberation cannot be accounted for by a single theoretical approach. Instead, a combination of functionalist and rational institutional design hypotheses account for variation in the extent to which IOs are designed to bring about diplomatic deliberation. By contrast, we do not find evidence for the theoretical expectation derived from liberal approaches. Our analysis revealed that three factors impact IOs’ DDDI scores. IOs are significantly more deliberative in their design, if they cover high politics, are smaller in size and are regional in character.

Our analysis in this article focuses on formal rules inhibiting and fostering deliberation between state actors in IOs. This is important because institutional designs are constitutive to interaction as they provide the formal rules not only of who is a member, who sets the agenda, who is how involved in the negotiations and how decisions are passed, but also on which topics decisions can be taken in the first place. Yet, neo-institutionalism suggests that institutional designs guide but do not determine actor behaviour (March and Olsen Reference March and Olsen1984; Powell and DiMaggio Reference Powell and DiMaggio1991; Hall and Taylor Reference Hall and Taylor1996). Thus, is could well be the case that in IOs which place great emphasis on speeding up decision-making by delimiting deliberative institutional design elements, such as the CAACI, actors engage in practice in more deliberation than the institutional design alone would lead us to expect. It would be beyond the scope of this contribution to examine theoretically and empirically how institutional rules are used in practice and whether and under what conditions diplomats create functional equivalents (e.g. deliberating in coffee breaks or alternative venues) in case IO designs strongly delimit deliberation in the main arena. Yet, studying the nexus between institutional design and actor practices is a fruitful field for future research in IOs as well as in institutions on the domestic level.

Taken together, there is not a ‘one size fits all’ approach when it comes to designing IOs. IOs have not all subscribed to the same choice on how strongly they seek to induce or prevent deliberation between diplomats. Which real-world effects variation in the extent to which IOs foster diplomatic deliberation brings about remains largely to be seen.

State of the art domestic-level deliberation research suggests that deliberation makes a difference (e.g. Carpini, Cook and Jacobs Reference Carpini, Cook and Jacobs2004; Bächtiger et al. Reference Bächtiger, Spörndli, Steenbergen and Steiner2005; Manin Reference Manin1987): while it reduces the speed of decision-making, it has positive implications for the problem-solving effectiveness and legitimacy of political systems in the domestic realm.

The same might also apply to the international realm. IOs with strongly deliberative institutional design are likely to induce diplomatic deliberation. While the exchange of principled positions and reasons between the actors can require considerable time and slow down the effectiveness of passing IO outcome documents – especially if IOs are large in size – deliberation can also have positive effects at the same time. Diplomatic deliberation can be conducive to IO decisions beyond the lowest common denominator since final outcomes are grounded in sound reasons (Eckl Reference Eckl2017). Ideally, diplomatic deliberation brings about outcomes in the interest of all stakeholders rather than outcomes that reflect the relative bargaining power of a few great players. If outcomes rest on the agreement of all actors, public accountability of IO decisions is likely to increase, as all member states are collectively responsible for the outcomes. High-quality outcomes have further positive ramifications as they can generate legitimacy for the IO concerned (Reference Anderson, Bernauer and KachiAnderson, Bernauer and Kachi forthcoming), which in turn is also important to address the democratic deficit problem of today’s global governance (Reference Tallberg and ZürnTallberg and Zürn forthcoming). In short, with respect to IOs designed to foster deliberation we do expect a trade-off between a more limited speed of decision-making on the one hand, and high-quality outcomes as well as legitimacy on the other hand for governance beyond the nation state as well.

Acknowledgements

This article is part of a research project funded by the German Research Council (DFG), grant number PA 1257/5-1. We presented earlier versions of the article at the ISA conference 2018 and at the Drei-Länder-Tagung 2019 and are grateful for the constructive and lively discussions. In particular, we would like to thank Loriana Crasnic, Thomas Doerfler, James Hollway, Nilgün Önder, and Patrick Theiner. This article benefitted from the research assistance of Sarah Bordt, Chiara Fury, Lea Gerhard, Pauline Grimmer, Nicolas Koch, Sebastian Lehmler, Laura Lepsy, Laura Maghetiu, Fabiola Mieth, Leonardo Rey, Laurenz Schöffler, Jannik Schulz, Leylan Sida, Edward Vaughan and Philipp Wagenhals, who helped with collecting the primary law sources and the rules of procedures, coding the IO institutional designs, and supporting us in compiling the database.

Appendix

Table A1. Coding scheme diplomatic deliberative design elements of IOs

Table A2. DDDI scores

Table A3. Summary statistics independent variables