Background

The populations’ ageing and changes in family and working life call for changes in organising care (Daatland and Herlofson, Reference Daatland and Herlofson2003; Haberkern and Szydlik, Reference Haberkern and Szydlik2010). In recent years, the accessibility of publicly funded services has decreased and social networks’ care responsibility has become more emphasised (Triantafillou et al., Reference Triantafillou, Naiditch, Repkova, Stiehr, Carretero, Emilsson, Di Santo, Bednarik, Brichtova, Ceruzzi, Cordero, Mastroyiannakis, Ferrando, Mingot, Ritter and Vlantoni D2010; Broese van Groenou and de Boer, Reference Broese van Groenou and de Boer2016; van den Broek et al., Reference van den Broek, Dykstra and van der Veen2019). These policy shifts suggest that reducing care provisions will be compensated by increased informal care and that the message thus given will be incorporated in general care attitudes. However, it is not clear whether this assumption is realistic (Verbakel, Reference Verbakel2017a). Recent Dutch studies do not give a clear answer to the question whether care attitudes are shifting towards the direction desired. Although public opinion seems to shift towards more family responsibility, most Dutch citizens still think elderly care is mainly the government's responsibility (Verbakel, Reference Verbakel2014; de Klerk et al., Reference de Klerk, de Boer, Plaisier and Schyns2017). More recent insights into care attitudes are needed to get a better understanding of Dutch citizens’ preferences regarding the division of care responsibilities.

Scientific research has devoted increasing attention to care-givers’ profiles and trends in informal care provision (Triantafillou et al., Reference Triantafillou, Naiditch, Repkova, Stiehr, Carretero, Emilsson, Di Santo, Bednarik, Brichtova, Ceruzzi, Cordero, Mastroyiannakis, Ferrando, Mingot, Ritter and Vlantoni D2010; Verbakel, Reference Verbakel2017a, Reference Verbakel2017b), but not to understanding care attitudes (Dykstra and Fokkema, Reference Dykstra and Fokkema2012; van den Broek et al., Reference van den Broek, Dykstra and van der Veen2015). Understanding differences in care attitudes enables professionals to align better with people's preferences and helps policy makers to understand how formal services could be (re)arranged to meet a wide variety of expectations (Daatland and Herlofson, Reference Daatland and Herlofson2003; Dykstra and Fokkema, Reference Dykstra and Fokkema2012; van den Broek et al., Reference van den Broek, Dykstra and van der Veen2015). The Netherlands provides an interesting context, because of its generous welfare state arrangements (van den Broek et al., Reference van den Broek, Dykstra and van der Veen2019) and individualistic cultural norms (Dykstra and Fokkema, Reference Dykstra and Fokkema2012). Changes in Dutch long-term care policies are exemplary to other European countries which are trying to shift care responsibilities towards the family or social networks as well (Verbeek-Oudijk et al., Reference Verbeek-Oudijk, Woittiez, Eggink and Putman2014). We will therefore explore recently expressed care attitudes of Dutch citizens of various backgrounds.

Diversity in care attitudes

Care attitudes are defined as citizens’ opinions regarding the division of care responsibilities between family and/or social networks and the welfare state. Several studies discern specific aspects of such normative care beliefs, such as filial norms or responsibility, on the one hand, and the extent to which individuals consider the state responsible for organising care, on the other (Daatland and Herlofson, Reference Daatland and Herlofson2003; van den Broek et al., Reference van den Broek, Dykstra and van der Veen2015). In this study, we will focus on both care-giving norms and welfare state orientation to investigate care attitudes. Because we focus on care responsibilities in families and/or social networks, we broaden the often-used definition of filial norms (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Peek and Coward1998; Daatland and Herlofson, Reference Daatland and Herlofson2003; Gans and Silverstein, Reference Gans and Silverstein2006). Care-giving norms refer to the recognised duties and obligations that define all citizens’ social role with respect to close ones who need care (Gans and Silverstein, Reference Gans and Silverstein2006). Welfare state orientation reflects expectations concerning the relative responsibilities of the social network and the welfare state (Daatland and Herlofson, Reference Daatland and Herlofson2003). Some authors find an association between those aspects: citizens with strong filial norms contribute less care responsibility to the state and thus emphasise the networks’ responsibility (Daatland and Herlofson, Reference Daatland and Herlofson2003; Verbakel, Reference Verbakel2014). However, there are also indications that strong filial norms can go along with a strong preference for the state providing care (Dykstra and Fokkema, Reference Dykstra, Fokkema and de Boer2009). Because there seems to be no unequivocal answer to how both aspects of care attitudes are associated, we will look into both aspects and its determinants separately, to grasp care attitudes of citizens fully (van den Broek et al., Reference van den Broek, Dykstra and van der Veen2015).

To be able to understand differences in care attitudes, we use intersectionality. The concept of intersectionality, coined by Crenshaw at the end of the 1980s (Davis, Reference Davis2008; Bauer, Reference Bauer2014), offers the opportunity to gain critical insights of how care-giving issues are framed and formed by diversity (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Sethi, Duggleby, Ploeg, Markle-Reid, Peacock and Ghosh2016). ‘Intersectionality’ refers to the interaction between dimensions of difference in individual lives, social practices, institutional arrangements and cultural ideologies, and the consequences of these interactions where distribution of power is concerned (Davis, Reference Davis2008; Hankivsky, Reference Hankivsky2014). Within this reasoning care can be seen and experienced as an inequality-creating phenomenon as a result of institutionalised patterns of cultural norms and values (Akkan, Reference Akkan2020). Young women, for instance, may face inequalities because of care-giving expectations that hinder them to pursue other ambitions in their lives. Akkan (Reference Akkan2020) argues that such feminist thinking around care issues takes its strength from the contextuality approach, that states that the morality and the practice of care are intertwined. Hancock (Reference Hancock2007) defines intersectionality as a body of normative theory and empirical research that proceeds under six key assumptions: (a) more than one category of difference plays a role, (b) these categories should be equally attended to and the relationship between them is an open empirical question, (c) categories are conceptualised as dynamic productions of individual and institutional factors, (d) each category has within-group diversity, (e) categories should be examined at multiple levels, and (f) attention to both empirical and theoretical aspects of the research question is needed (Hancock, Reference Hancock2007). Other scholars present dimensions of inequality as closely intertwined and argue as well that these forms of stratification need to be studied in relation to each other (Choo and Ferree, Reference Choo and Ferree2010; Winker and Degele, Reference Winker and Degele2011; Hankivsky, Reference Hankivsky2014). In care-giving research, the intersectionality approach is nowadays seen as an important tool to articulate the multi-dimensional and relational nature of care-giving and the social conditions under which care is provided (Chappell et al., Reference Chappell, Dujela and Smith2015; Dilworth-Anderson et al., Reference Dilworth-Anderson, Moon and Aranda2020). However, little is known about intersectionality in care attitudes.

Whilst investigating care attitudes, researchers have found relationships with several diversity characteristics, such as cultural backgrounds and socio-cultural circumstances (Daatland and Herlofson, Reference Daatland and Herlofson2003; Gans and Silverstein, Reference Gans and Silverstein2006; Beneken genaamd Kolmer et al., Reference Beneken genaamd Kolmer, Tellings and Gelissen2008; Dykstra and Fokkema, Reference Dykstra and Fokkema2012; Verbakel, Reference Verbakel2014; van den Broek et al., Reference van den Broek, Dykstra and van der Veen2015; Santoro et al., Reference Santoro, Van Liew, Holloway, McKinnon, Little and Cronan2016). These examples underline the importance of investigating not only personal dimensions of diversity, but also situational circumstances. The intersectional approach allows us to do so, as it conceptually focuses on both personal and situational dimensions of diversity, assuming associations between citizens’ social identities and situational circumstances. Thus, this approach can provide insight into the mutual reinforcement of these characteristics in relation to care attitudes (Hancock, Reference Hancock2007; Hankivsky and Cormier, Reference Hankivsky and Cormier2009; Rouhani, Reference Rouhani2014). Not only focusing on single dimensions of diversity but investigating interactions among these dimensions as well could better reflect the complexity of shaping care attitudes (Giesbrecht et al., Reference Giesbrecht, Crooks, Williams and Hankivsky2012; Hunting, Reference Hunting2014).

Following the intersectional approach, we consider the relationships among diversity characteristics as an open empirical question (Hancock, Reference Hancock2007; Hankivsky and Cormier, Reference Hankivsky and Cormier2009), which means that no dimensions of diversity will be given favour in our analysis (McCall, Reference McCall2005; Giesbrecht et al., Reference Giesbrecht, Crooks, Williams and Hankivsky2012). However, we did decide to use a pragmatic classification of dimensions of diversity in order to increase the readability of this study. When we write about ‘primary dimensions of diversity’ we mean personal diversity characteristics considering social identities, and writing about ‘secondary dimensions of diversity’ we mean situational circumstances (Loden and Rosener, Reference Loden and Rosener1990; Hankivsky and Cormier, Reference Hankivsky and Cormier2009).

Diversity characteristics and hypotheses

Primary dimensions

Previous studies are ambiguous about the association between gender and filial norms. In some studies women are assumed to have stronger filial norms than men, making caring a gendered concept (Daatland and Herlofson, Reference Daatland and Herlofson2003; Dykstra and Fokkema, Reference Dykstra and Fokkema2012). According to van den Broek et al. (Reference van den Broek, Dykstra and van der Veen2015), however, European studies reveal men having stronger filial norms than women. Dutch studies on welfare state orientation have established that women more often consider the government responsible for care (van den Broek et al., Reference van den Broek, Dykstra and van der Veen2015; Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Meulenkamp and de Jong2017). Younger people have stronger filial norms (Gans and Silverstein, Reference Gans and Silverstein2006; Dykstra and Fokkema, Reference Dykstra and Fokkema2012), but at the same time they assign the care responsibility to the government more often than elderly people (Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Meulenkamp and de Jong2017). A relationship between (self-reported) health status and care attitudes was found in one study, revealing that a worse health status leads to considering the state responsible for care (Verbakel, Reference Verbakel2014). Various researchers (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Peek and Coward1998; Blieszner and Bedford, Reference Blieszner and Bedford2012) have found ethnic differences: people sharing collectivistic values, such as many from non-Western cultures, perceive care as a family responsibility, while care-givers from individualistic cultures rely on external services (Santoro et al., Reference Santoro, Van Liew, Holloway, McKinnon, Little and Cronan2016). Dykstra and Fokkema (Reference Dykstra and Fokkema2012) state that migrants living in the Netherlands have stronger filial norms than people of Dutch origin.

From the literature on primary dimensions it can be concluded that care-giving norms and welfare state orientation have partly different determinants. Therefore, our first hypothesis (Hypothesis 1) is formulated as follows: where strong care-giving norms are assumed to be overrepresented in men, younger persons, those in good health and those of non-Western origin, a stronger government orientation can be expected to be seen within women, younger persons, those with health problems and those of Dutch or other Western origin.

Secondary dimensions

Studies show higher-educated people having a more individualistic lifestyle and weaker care-giving norms (Gans and Silverstein, Reference Gans and Silverstein2006; Dykstra and Fokkema, Reference Dykstra and Fokkema2012; van den Broek et al., Reference van den Broek, Dykstra and van der Veen2015). Higher-educated people place less responsibility on the government (Verbakel, Reference Verbakel2014; Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Meulenkamp and de Jong2017). Employed or financially advantaged families show a lesser sense of obligation to provide care themselves (Gans and Silverstein, Reference Gans and Silverstein2006; van den Broek et al., Reference van den Broek, Dykstra and van der Veen2015). People with a job have less spare time to provide care, so it is expected that they adjust their care-giving norms downwards (Dykstra and Fokkema, Reference Dykstra and Fokkema2012). Hoefman et al. (Reference Hoefman, Meulenkamp and de Jong2017) found an association between working part-time and assigning the government more care responsibility. People with children prove to attribute families fewer caring responsibilities, because parents may not want to burden their children (Dykstra and Fokkema, Reference Dykstra and Fokkema2012; van den Broek et al., Reference van den Broek, Dykstra and van der Veen2015). Religious people have stronger filial norms than others (Dykstra and Fokkema, Reference Dykstra and Fokkema2012; Mair et al., Reference Mair, Quiñones and Pasha2015) and feel a stronger family care responsibility (Daatland and Herlofson, Reference Daatland and Herlofson2003; Verbakel, Reference Verbakel2014). Care attitudes may predict the tendency of people to provide informal care (Silverstein et al., Reference Silverstein, Parrott and Bengtson1995, Reference Silverstein, Gans and Yang2006; Dykstra and Fokkema, Reference Dykstra and Fokkema2012), but the decision to actually provide informal care is also influenced by other circumstances such as the need for care, perceived barriers and social context (Broese van Groenou and de Boer, Reference Broese van Groenou and de Boer2016). Being a care-giver may lead to endorsing strong care-giving norms (Silverstein et al., Reference Silverstein, Parrott and Bengtson1995, Reference Silverstein, Gans and Yang2006; Dykstra and Fokkema, Reference Dykstra and Fokkema2012) as well as to asking the government to shoulder care responsibility (Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Meulenkamp and de Jong2017).

Many studies provided evidence on secondary dimensions of care attitudes. Based on these insights, we hypothesise (Hypothesis 2) that, on the one hand, people with lower education and those who are unemployed or financially disadvantaged, without children, religious and care-givers will have stronger care-giving norms. On the other hand, people who have higher education and those who are employed or financially advantaged, have children, are not religious and are not care-givers will consider the government responsible for care.

In addition to these hypotheses regarding diversity's direct influences on care attitudes, we investigate indirect influences as well. As mentioned before, in intersectional research, the relationships among diversity characteristics are viewed as an open empirical question in which an integrative analysis of the interaction between citizens’ social identities and situational circumstances is seen as a relevant approach (Hancock, Reference Hancock2007; Hankivsky and Cormier, Reference Hankivsky and Cormier2009). We thus hypothesise (Hypothesis 3) that there are interactions of primary and secondary diversity characteristics in our models. Specific literature on such interactions whilst investigating care attitudes is lacking. However, based on more general care-giving literature it is known that, for example, gender intersects with other axes of difference, such as culture, socio-economic status, marital status and geography (Giesbrecht et al., Reference Giesbrecht, Crooks, Williams and Hankivsky2012; Browning, Reference Browning2021), and that age is associated with other differences such as socio-economic status, employment status, marital status and being a care-giver or not (Kenny et al., Reference Kenny, King and Hall2014; Browning, Reference Browning2021). Compared to other studies on care attitudes in which these interactions are not considered, these insights potentially better reflect the complexity of shaping care attitudes, as the focus is based not only on differences on single dimensions of diversity (Giesbrecht et al., Reference Giesbrecht, Crooks, Williams and Hankivsky2012; Hunting, Reference Hunting2014).

Methods

Sample

We use two datasets of the Netherlands Institute for Social Research which contained citizens’ opinions about society. These datasets are based on surveys conducted in 2016 and 2018. The first quantitative study (2016) was carried out among a representative sample of the Dutch population aged 16 and older. Citizens within this sample (N = 5,387) received a letter about the study in which the visit of an interviewer at home was announced. Trained interviewers executed the interviews at home using a digital questionnaire. Out of this sample eventually 2,690 respondents participated in the study (Coumans and Knops, Reference Coumans and Knops2017). The second quantitative study was conducted the same way in 2018. Out of the total representative sample (N = 4,570) eventually 2,609 respondents participated (Coumans and Knops, Reference Coumans and Knops2019). For the study described in this paper, we combined the datasets of 2016 and 2018 to get a robust dataset of 5,293 respondents aged 16 and over.

Measurements

Care-giving norms are measured by three items combined into a 1–5 scale (Cronbach's α = 0.62). The scale reflects to what degree citizens think that (a) people with long-term illness or limitations should receive help as much as possible from family, friends or neighbours; (b) adult children are obliged to provide care to their parents when in need; and (c) it is good that the government expects citizens to provide care to each other in case of chronic illness or disability. A score of 1 reflects the weakest care-giving norm and a score of 5 the strongest, meaning that persons are more likely to think persons in need of care should receive help from their families and/or social networks.

Welfare state orientation is often measured on a scale ranging from ‘completely a state responsibility’ to ‘completely a family responsibility’ (Daatland and Herlofson, Reference Daatland and Herlofson2003; Haberkern and Szydlik, Reference Haberkern and Szydlik2010; Verbakel, Reference Verbakel2014; van den Broek et al., Reference van den Broek, Dykstra and van der Veen2015). To gauge this, respondents were asked whether they think elderly care is mainly the government's responsibility or mainly the family's. Possible answers were (a) mainly a government task, (b) more a government task than a family task, (c) more a family task than a government task or (d) mainly a family task. As in the care-giving norm scale, the highest value reflects a care attitude holding the family most responsible.

As independent variables we used all available diversity characteristics in the dataset that could be associated with care attitudes. We included gender (male or female), age (16–34, 35–64 or 65+ years old), self-reported health status (not limited or limited) and origin (Dutch/other Western or non-Western) as primary dimensions of diversity. Additionally, we included level of education (lower, intermediate or tertiary education), employment status (unemployed, working less than 12 hours a week or working more than 12 hours a week), income (divided into four groups, rising from low income (first quartile) to high income (fourth quartile) within the sample), household situation (single household, living with children or other household situations, e.g. married or unmarried couples without children), religiosity (religious or non-religious) and being a care-giver (yes or no) as secondary dimensions. To be able to interpret the tested interaction terms better, all independent variables were categorised.

Analytic strategy

Intersectionality-informed analysis incorporates both additive and multiplicative approaches (Rouhani, Reference Rouhani2014). First, we explored differences on care-giving norms and welfare state orientation between citizens by comparing means in a bivariate analysis (not presented in a table). Second, we are able to explore the effects of primary and secondary dimensions in relation to care-giving norms and welfare state orientation. Multivariate linear regression analyses were conducted to investigate these effects on care-giving norms (Table 2, Model 1a), and ordered probit regression analyses were conducted to investigate these effects on welfare state orientation (Table 3, Model 2a). By adding the care-giving norm scale to our second regression model (Model 3), we were able to explore the extent to which care-giving norms and welfare state orientation are related (not presented in a table). All models are visualised in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Visualization of regression models 1, 2 and 3.

Finally, interaction terms were individually added to Models 1a and 2a to examine the relationship between mutually related factors to care-giving norms and welfare state orientation. Results are presented in Models 1b and 2b (Tables 2 and 3). Because of the explorative character of our study, the level of significance is p < 0.01.

Results

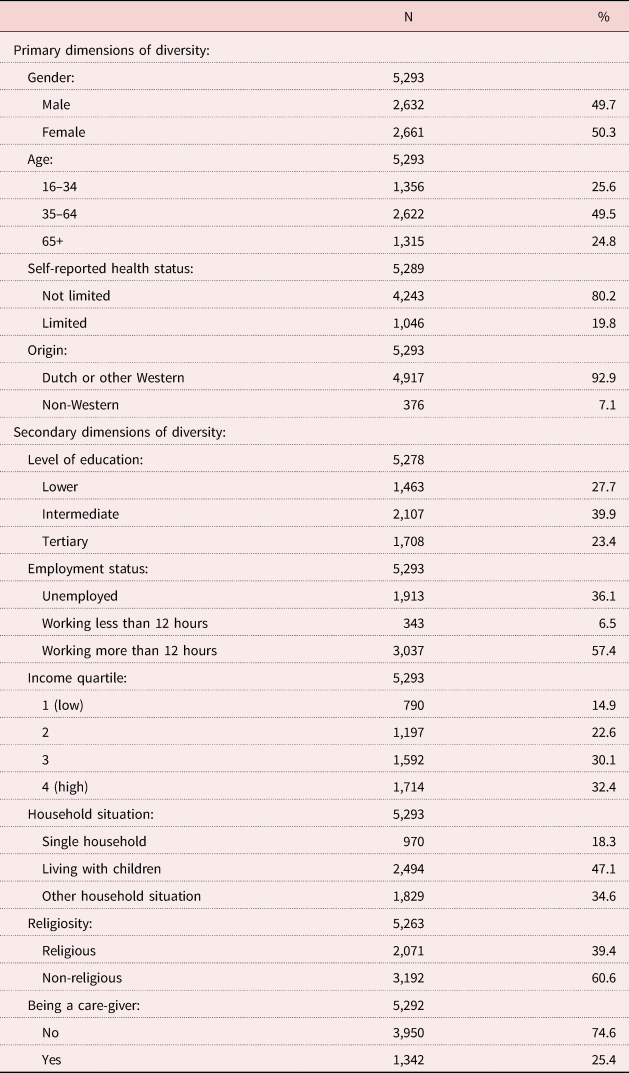

Dutch citizens’ care-giving norms are relatively strong, with no scores below 2.78 on a 1–5 scale. Their welfare state orientation shows another pattern with a lowest score of 2.08 on a 1–4 scale (not presented in a table). Table 1 provides an overview of the respondents who are included in the dataset based on both primary and secondary diversity characteristics.

Table 1. Respondents’ characteristics

Association between diversity characteristics and care attitudes

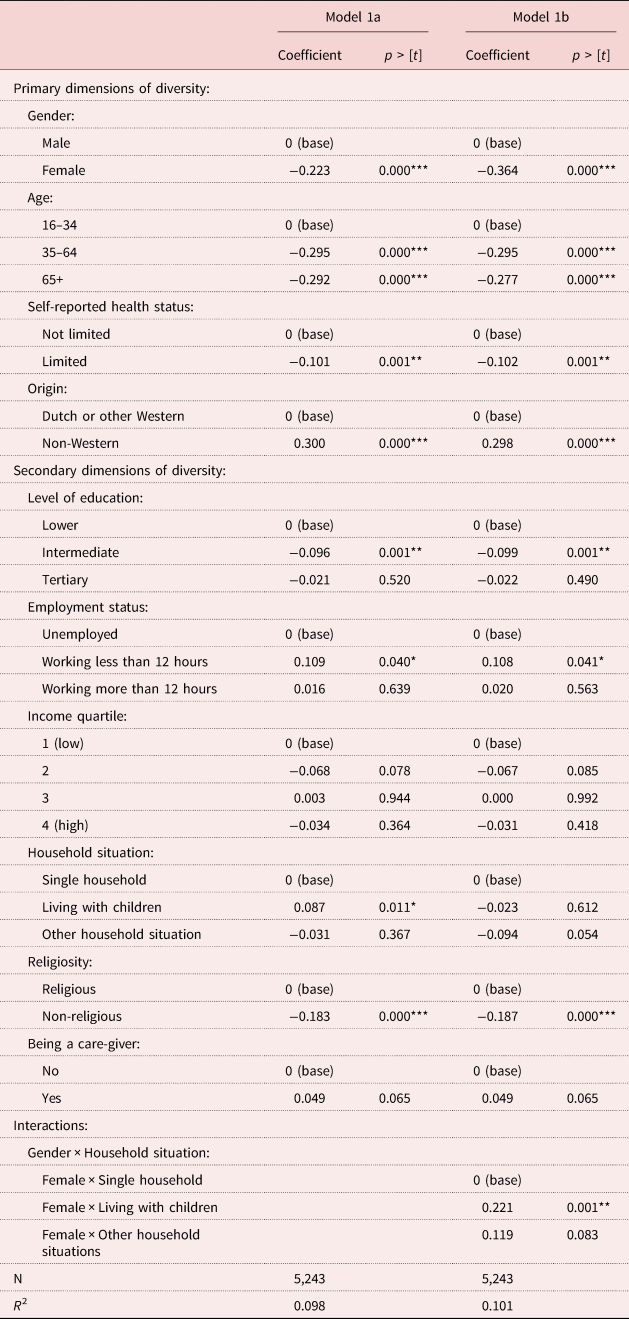

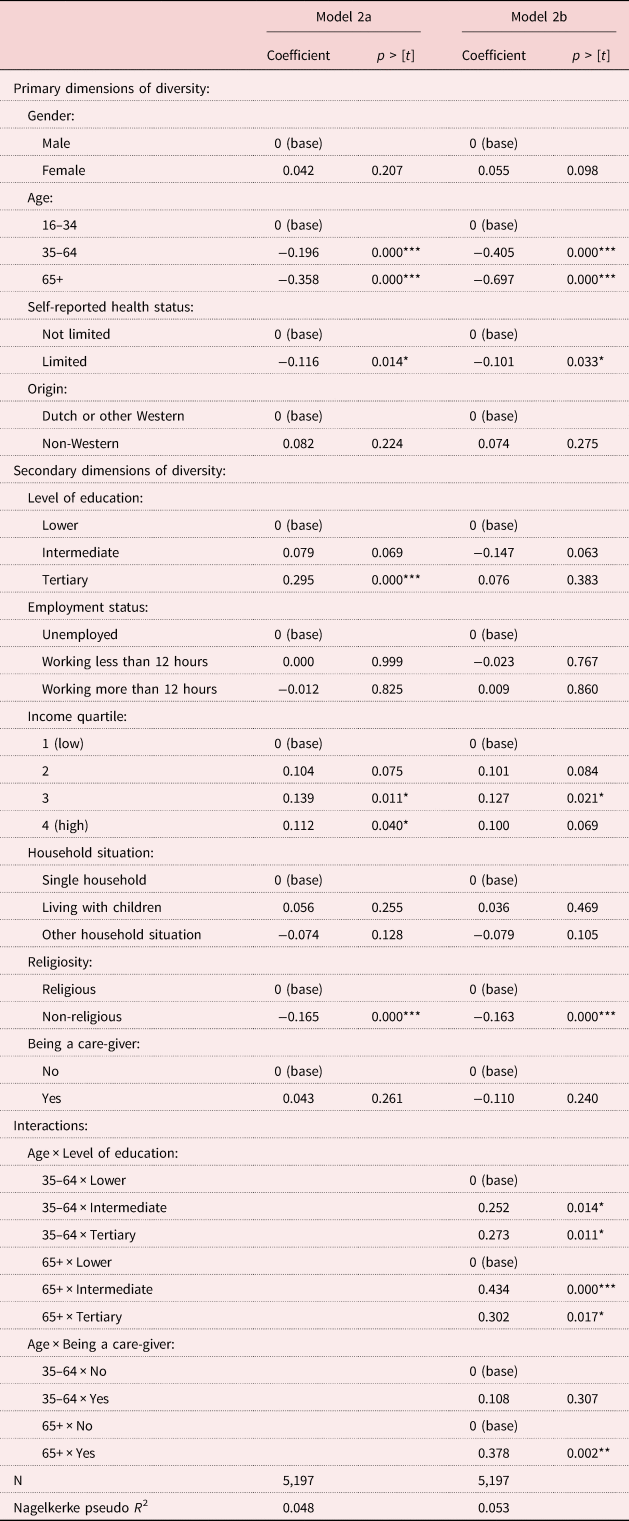

We used multivariate linear and ordered probit regression analyses to investigate the individual effects of the independent variables on care attitudes (Tables 2 and 3). Diversity characteristics explain a relatively small proportion of the variance in both the care-giving norm scale (R 2 = 0.098) and welfare state orientation (pseudo R 2 = 0.048).

Table 2. Linear regression models: care-giving norm (Model 1)

Significance levels: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Table 3. Ordered probit models: welfare state orientation (Model 2)

Significance levels: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Although all of the primary dimensions of diversity are associated with the care-giving norm scale, only age is associated with people's welfare state orientation. Being female is negatively associated with the care-giving norm scale (−0.22). This also goes for citizens who are aged over 35 (−0.29), who face health limitations (−0.10) and who are of Dutch or other Western origin. Looking at welfare state orientation, it seems that the older people are, the smaller the chance they think care for people in need is mainly the family's responsibility. Differences in welfare state orientation based on gender, health and origin were not significant in the multivariate analyses.

Looking at secondary dimensions of diversity, level of education and religiosity turn out to be significantly associated with care attitudes: an intermediate level of education is negatively associated with the care-giving norm scale (−0.10), as is being non-religious (−0.18), indicating a higher chance of having weaker care-giving norms. In regards to welfare state orientation, the same pattern was found for religiosity, but for level of education the results are different: people with tertiary levels of education have a higher chance of assigning more responsibility to the family instead of the government. Other differences with secondary dimensions of diversity were not significant in the multivariate analyses.

To assess whether citizens with strong care-giving norms assign less responsibility for care to the state, we added the care-giving norm scale to our second model. The care-giving norm scale was positively associated with welfare state orientation (0.63, p ⩽ 0.001, not presented in a table), corroborating the assumption that citizens with strong care-giving norms attribute less responsibility for care to the state (Daatland and Herlofson, Reference Daatland and Herlofson2003; Verbakel, Reference Verbakel2014). The care-giving norm scale increased the explanatory power of the model (pseudo R 2 = 0.096, not presented in a table).

Interactions

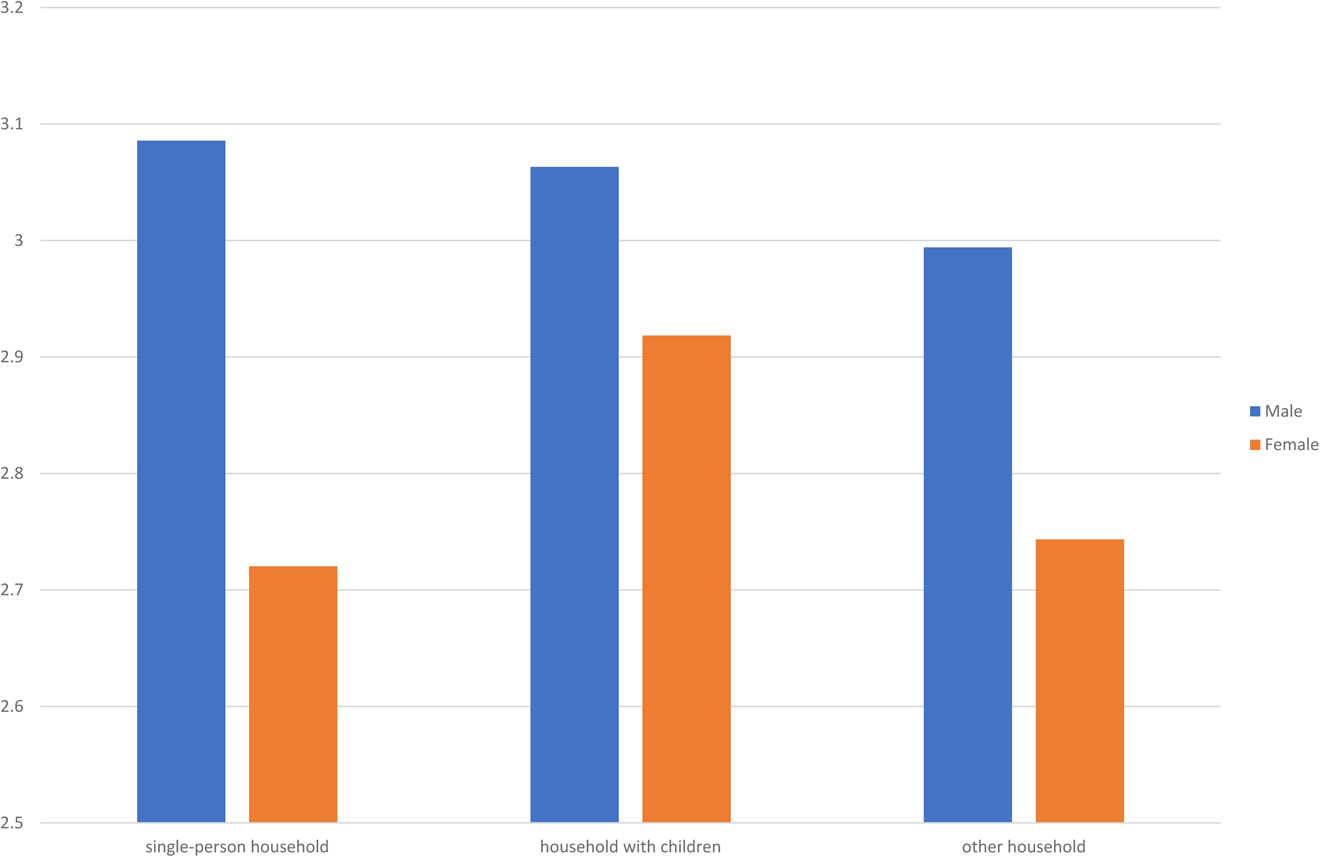

We used multiplicativity to look into the conditional effects of intersecting diversity characteristics. Results are presented in Models 1b and 2b (Tables 2 and 3). In the first model, an interaction was found between gender and household situation. Women living with children have stronger care-giving norms than those in single or other household situations. This difference does not apply to men (Figure 2). After adding this interaction, the associations found in the initial model (Table 2) remain significant.

Figure 2. Visualization interaction care-giving norms – gender and household situation.

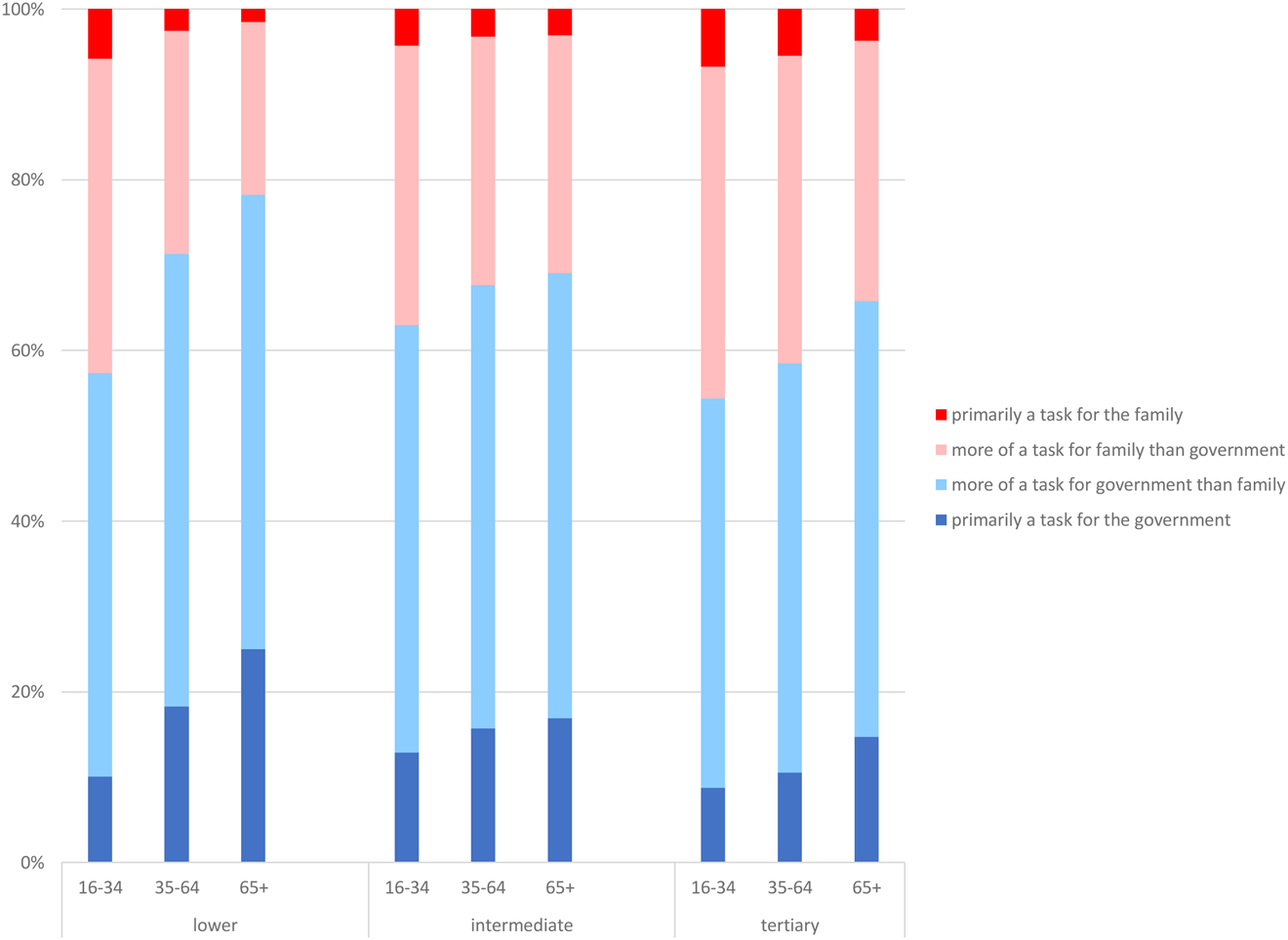

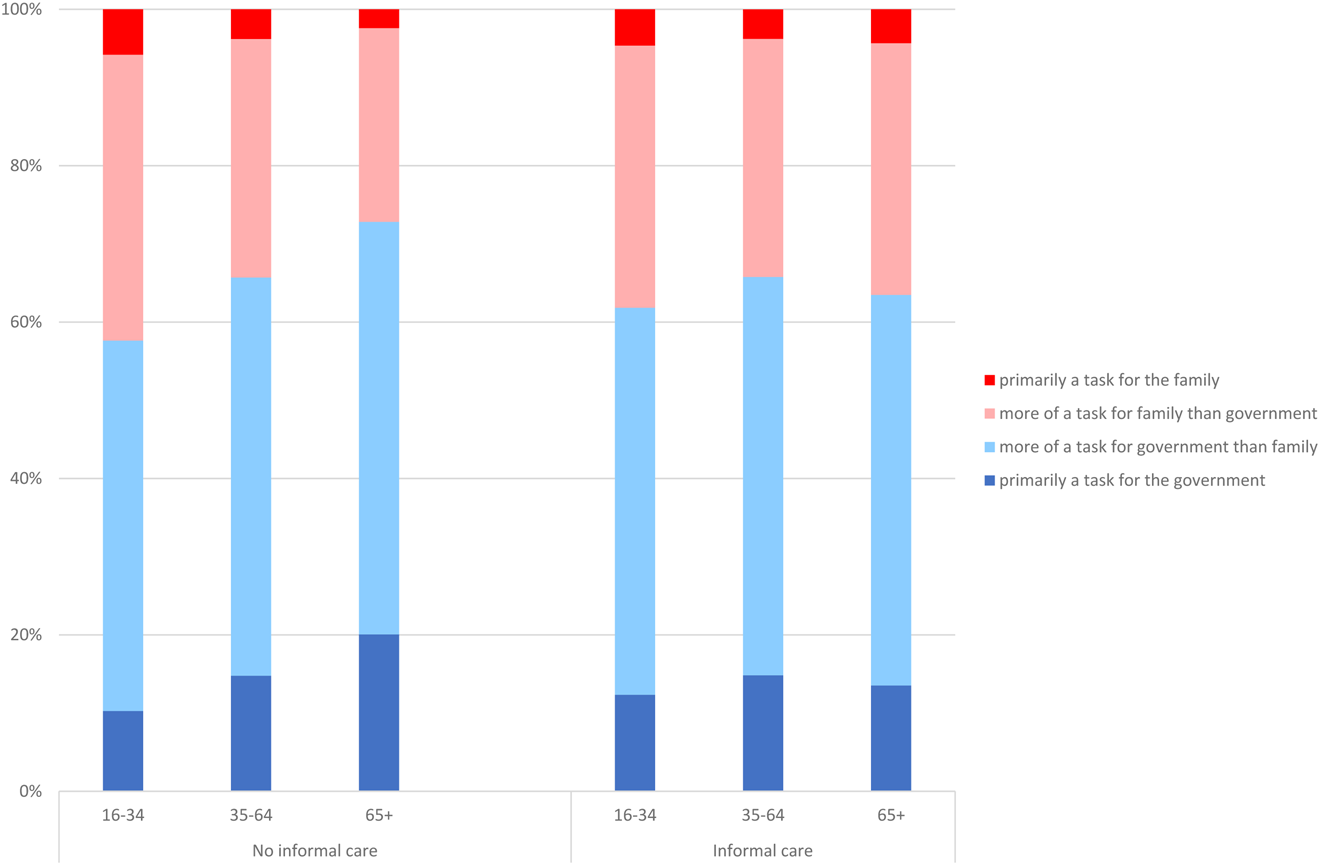

In the second model, interactions were found between age and level of education (Figure 3) and age and being a care-giver (Figure 4). People with a lower level of education assign relatively more responsibility to the government than the family, and once people are older the proportion of people considering the government responsible increases. This effect is less visible among groups with intermediate and tertiary education. Citizens aged 65 or older who are providing informal care assign more care responsibility to the family instead of the welfare state, compared to people who do not provide informal care. After adding these interactions to the initial model (Table 3), the main effect of level of education is no longer significant.

Figure 3. Visualization interaction welfare state orientation – age and level of education.

Figure 4. Visualization interaction welfare state orientation – age and being a caregiver.

Discussion

Our study sheds light on the distinct pathways of care attitudes of citizens. Using a large national representative sample of more than 5,000 respondents, it was shown that care attitudes are mixed, because care-giving norms of Dutch citizens are relatively strong. People also consider care for persons with disabilities and older people a state responsibility though.

Hypothesis 1 on care-giving norms was supported by our results. We observed that men's care-giving norms are stronger than women's, and that citizens in good health and people of non-Western origin have strong care-giving norms. The expected differences in welfare state orientation based on gender (van den Broek et al., Reference van den Broek, Dykstra and van der Veen2015; Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Meulenkamp and de Jong2017) were not found. Also, contrary to our expectation, younger people assign relatively more responsibility to the family and have stronger care-giving norms as well. Based on our results, we cannot properly explain why these results for younger people differ from our expectations. Younger people may be more accustomed to the decline of publicly funded services and the withdrawal of the welfare state than others. However, more in-depth research would be needed to be able to interpret these results better. Our multivariate analyses showed no significant associations between health problems, origin and welfare state orientation.

The expected relation of secondary diversity characteristics and care attitudes (Hypothesis 2) was partly supported by our results. Higher-educated people do attribute relatively more care responsibility to the family than to the government, and care attitudes of those who are religious are stronger than of those who are not. No significant differences in care attitudes were found based on employment status, income, household situation and being a care-giver or not. These results are somewhat surprising, as in the intersectional approach, associations between citizens’ social identities and situational circumstances are assumed (Hancock, Reference Hancock2007; Hankivsky and Cormier, Reference Hankivsky and Cormier2009). The reason might be that citizens’ care attitudes were investigated within the Dutch context of generous welfare state arrangements (van den Broek et al., Reference van den Broek, Dykstra and van der Veen2019) and individualistic cultural norms (Dykstra and Fokkema, Reference Dykstra and Fokkema2012), causing favourable circumstances for citizens (e.g. possibilities to work in part-time jobs, high-quality social services). Future research would therefore need other dimensions of diversity to be able to investigate the influence of situational circumstances on care attitudes of people. Specific care-giving research suggests that contextual factors such as cultural, economic and health system characteristics are significant (Fletcher et al., Reference Fletcher, Miaskowski, Given and Schumacher2012). More in general, dimensions such as socio-cultural environment, political differences or geography are suggested to be included (Hankivsky and Cormier, Reference Hankivsky and Cormier2009; Rouhani, Reference Rouhani2014). Unfortunately, our dataset did not include such determinants.

To explore the extent to which care-giving norms and welfare state orientation are related, we added the care-giving norm into the analysis of welfare state orientation. This increased the explanatory power of the welfare state orientation model. This indicates that there is an association between both aspects of care attitudes. We assume that the increased explanatory power of the model means that diversity is probably foremost associated with care-giving norms, and that care-giving norms are subsequently associated with citizens’ welfare state orientation. This is in line with the literature assuming that subjective norms influence behavioural intentions, and that the reverse does not apply (Daatland and Herlofson, Reference Daatland and Herlofson2003). This lack of clarity calls for more research regarding whether and how care attitudes of citizens evolve from care-giving norms into welfare state orientation and how this interacts with actual care-giving behaviour.

We found evidence for an interaction between primary and secondary dimensions of diversity. Hypothesis 3 is thus partly supported by our observations. People with lower levels of education assign relatively more responsibility to the government than to the family, but once people are older the proportion of people considering the government responsible increases. This may be related to the decline of filial norms as people get older (Gans and Silverstein, Reference Gans and Silverstein2006). Women who live with children have stronger care-giving norms, whilst this difference is absent for men. Possibly, this is caused by the persistence of gender role differentiation in modern families (Silverstein et al., Reference Silverstein, Gans and Yang2006; Dykstra and Fokkema, Reference Dykstra and Fokkema2012). Older care-givers assign relatively more responsibility to the family than to the government compared to non-care-givers. This difference is absent for younger people. Possibly this is because the likelihood of providing care increases with age or because older care-givers are more altruistic (Peng and Anstey, Reference Peng and Anstey2019). Another explanation might be that older care-givers mainly help their partner and younger care-givers help their parents (de Klerk et al., Reference de Klerk, de Boer, Plaisier and Schyns2017). The intersectional approach provided insights into the mutual reinforcement of these characteristics in relation to care attitudes. Without this approach, these groups with specific care attitudes would be overseen while in these groups inequality may arise. For example, the persistence of gender role differentiation in modern families may have consequences for (the absence of) fair opportunities for both men and women who provide informal care whilst having children, as suggested for example by Browning (Reference Browning2021).

This study also has limitations. First, the intersectional approach could have been used even more in detail in our analysis. We investigated interactions between primary and secondary dimensions of diversity, but not between primary or between secondary dimensions. Future research using this type of analysis could expose even more accurate insights about differences in care attitudes. This may expose specific groups who are at risk of unequal opportunities based on their care attitudes in combination with relevant determinants that influence actual care-giving behaviour. For example, this could provide specific information about young women or men of non-Western origin. Furthermore, using qualitative methods in follow-up research could provide complementary insights into the way power shapes dimensions of diversity and into the dynamic interaction between primary and secondary diversity dimensions (Hancock, Reference Hancock2007; Grace, Reference Grace2014; Hankivsky, Reference Hankivsky2014). Second, the low explanatory strength of our models may be caused by our measuring methodology. For example, our care-giving norm scale (R 2 = 0.098) could be further improved by integrating items from the scale developed by Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Peek and Coward1998) to measure filial norms. This may enhance the explanatory strength of the model.

Conclusions

Based on our intersectional approach to investigate care attitudes, we conclude that primary dimensions of diversity are more related to care attitudes than secondary dimensions: gender, age, self-reported health and origin are significantly related to care-giving norms. Furthermore, age is significantly related to welfare state orientation, whereas only level of education and religiosity are significantly related to both care-giving norms and welfare state orientation. Combined with the finding that several dimensions are related, such as age and care-giving are, we conclude that intersectionality is a valuable approach to explore diversity in relation to care attitudes. As it turns out, care attitudes are in some cases indeed shaped by multi-dimensional processes (Hunting, Reference Hunting2014). Insights into these differences in care attitudes offer professionals the opportunity to align better with citizens’ attitudes. Talking about care attitudes could improve clarity about provided care, which is important to improve collaboration between informal and formal care-givers (Wittenberg et al., Reference Wittenberg, Kwekkeboom, Staaks, Verhoeff and de Boer2018). Institutions that provide training in the areas of social work and (allied) health can use our insights to give upcoming professionals a better understanding of differences between groups of citizens regarding care attitudes. Expertise and attitudes of social workers and (allied) health professionals can also be expanded using our insights.

One of the possible consequences of more focus on informal care policy is that the corroborating care attitudes become more complex, as people and sub-groups vary to a large extent in their care-giving norms and welfare state orientation. The differences shown in our study reflect the fact that populations are diverse (Vertovec, Reference Vertovec2007) and that one cannot make generalisations of all citizens about their care attitudes. In the relatively new Dutch long-term care model, more emphasis is placed on providing informal care (Broese van Groenou and de Boer, Reference Broese van Groenou and de Boer2016; van den Broek et al., Reference van den Broek, Dykstra and van der Veen2019). Combined with the fact that there will be a strong decrease in the number of potential care-givers in the future (Herrmann et al., Reference Herrmann, Michel and Robine2010), policy makers need to pay attention to groups of citizens who have less-strong care-giving norms. For those, it might be less obvious to actually provide informal care when needed (Peng and Anstey, Reference Peng and Anstey2019). On the other hand, it is important to make sure that people with strong care attitudes will not become overburdened because of their informal care tasks. Policy makers should realise that although many people are willing to help, they do expect some kind of commitment and help from the government as well.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jurjen Iedema, methodologist at The Netherlands Institute for Social Research, for his support during this research project.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design, interpretation of the data and drafting of the article, and approved the version to be published. Furthermore, the first, second and third authors conducted data analysis.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) (project number 023.011.009, Doctoral Grand for Teachers). NWO played no role in the design, execution, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was not required. Participants received written study information, and participation was elective. Data collection was in strict accordance with the national standard. At no time did the datasets contain direct identifiers.