On June 6, 1755, the Portuguese crown enacted a law abolishing—once again—the enslavement of Indigenous Americans.Footnote 2 The attempt to ban Indigenous slavery was integral to Portuguese imperial reforms in the second half of the eighteenth century for two reasons. First, it fostered alliances with Indigenous groups who played a critical role in the border-defining struggle between Spain and Portugal in South America. Second, Portuguese imperial reformers tried to pull Maranhão into the Atlantic economy by importing large numbers of African slaves to develop a cash crop economy of cotton and rice. These reforms combined to strengthen Portuguese rule over Northern Brazil. In Maranhão's colonial settlements, the abolition law produced contradictory effects. There, the century-long practice of raiding and trading Indigenous captives in the interior (sertões) left thousands of Indigenous people in bondage. The present article explores ruptures and continuities in the enslavement of Indigenous Americans as importation of African slaves rapidly increased.

The massive enslavement of Indigenous Americans in Northern Brazil has only recently started to receive scholarly attention.Footnote 3 Historians of colonial Brazil have traditionally interpreted Indigenous slavery as an institution typical of the peripheries; that is, São Paulo and Amazonia, the peripheries of sugar plantation areas.Footnote 4 New interpretations emerged when scholars overcame the tendency to analyze these regions in terms of what they lacked—sugar and African slaves—and started to take seriously what they had—different economic activities based on various forms of coerced Indigenous labor.

This scholarship has been essential to debunk the image of Amazonia as a region long neglected by the Portuguese crown and to expand the history of slavery beyond the African experience.Footnote 5 In fact, both the recruitment of Indigenous labor and the enslavement of Indigenous people were central to Portuguese policies, which proved wrong the alleged incompatibility between Indigenous slavery and colonial system over the long term.Footnote 6 Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, cocoa production and cattle raising, the primary local economic activities, depended almost exclusively on Indigenous labor recruited in multiple forms. The Portuguese crown responded to local pleas for additional labor and created conditions for this major population resettlement. The number of Indigenous workers recruited in the interior was estimated at 100,000–260,000. This figure is comparable to the number of African slaves laboring in the sugar industry in Northeastern Brazil and in mining operations in Southern/Central Brazil.Footnote 7

As scholars re-examine the number of Indigenous workers, the economic activities they supported, and the Portuguese policies regulating their recruitment, other historians have started to sketch the lives of Indigenous workers. Freedom suits have been an important source for understanding the lives of thousands of Indigenous workers forcibly displaced from the interior to colonial settlements. The pioneer work of David Sweet argued that Indigenous freedom suits were rare.Footnote 8 More recently, Márcia Mello reconsidered the exceptionality of Sweet's case study and offered the first comprehensive explanation for the different forums that Indigenous people could access to reclaim their freedom. In the eighteenth century, Indigenous Americans frequently used the Board of Missions (Junta das Missões), a tribunal composed of ecclesiastical and secular authorities for Indigenous affairs. The Board of Missions operated under the dual charge of authorizing wars against Indigenous groups, and hence their enslavement, and deciding over illicit enslavements, and hence their freedom.Footnote 9

Recently, other scholars have delved into the extant documents of the Board of Missions. Despite the fragmentary condition of the archival collection, they were able to better understand the place of the Board of Missions in the monarchy's architecture of power and how Indigenous people navigated the legal system in colonial Maranhão. Most of the litigants were female slaves, who also won the freedom of their families. The success of those freedom strategies depended on the appropriate mobilization of witnesses, the selection of legal representation, the legal arguments and proofs chosen by them, and the balance of power in local politics, since the composition of the Board of Missions changed over time.Footnote 10

Taken together, this body of scholarship still relies on a rigid boundary between the periods before and after the imperial reforms. This reliance obscures the continuities in Indigenous bondage. The different forms of labor recruitment ranged from slavery to forced or peaceful resettlement of Indigenous peoples. Yet, the customary slippage, to use the expression of another historian, between one mode of conscription and the other was not limited to the recruitment side of this large-scale process of resettlement.Footnote 11 The definition of Indigenous workers’ legal status was hazy, and was disputed once they entered settlers’ households.

This article focuses on the Indigenous population in Maranhão living outside the Indigenous villages and toiling in cities, settlers’ houses, and farms.Footnote 12 It analyzes the connection between mechanisms that allowed slavery (or forms of labor that resembled slavery) to persist and people's attempts to claim and preserve freedom or autonomy, through the strategic use of the índio status.Footnote 13 Two of those mechanisms that kept Indigenous laborers in bondage were social dependencies created within households, and the use of socio-racial classifications by the colonial society.

Some historians have argued that the 1755 abolition law was a “political fiction” or a “false freedom” and that Indigenous people continued to live under the same regimes of exploitation with a new name.Footnote 14 Based on baptismal records, wills, petitions, and legal cases, it is indeed possible to visualize the persistence of bonds of social dependency ranging from sex, intimacy, honor, and ritual kinship (compadrio). These bonds kept Indigenous workers and masters linked.Footnote 15 Yet, to say that nothing changed is to overlook the years of legal activism by Indigenous actors. Indigenous people were moving away from the legal status of “escravo” towards “do serviço,” and this was not the result of colonial officials simply following the new abolition law of 1755. Instead, it was a bottom-up process of abolition. Indigenous workers learned how to use the channels offered by Portuguese colonialism, and the knowledge about the 1755 law, which circulated among the workers, was only another weapon.Footnote 16

The transition from one legal status to another was not seamless and not without conflict. It primarily involved public reputation; that is, being recognized as an índio(a) in the community. Whenever conflict emerged, one's ability to prove his or her free status through written documents or genealogy was essential. Under Portuguese colonialism, the status of índio offered some constraining obligations, such as the requirement to participate in labor drafts, and some special rights, like the payment for their labor, the freedom to choose whom one would serve, and mobility. The protection offered by the Portuguese monarchy and settlers could work both ways. Indigenous workers (or their masters) requested permissions to stay in the households that they served for years. They also used the índio status to delineate spaces of autonomy and independence from former masters.Footnote 17

Building on the work of Maria Resende, this article stresses how Indigenous people's legal activism forced masters to increase the use of socio-racial classification.Footnote 18 In the decades of the 1760s and 1770s, with the growth of the transatlantic slave trade and the aftermath of the publication of the law abolishing Indigenous slavery, the status “slave” became closely connected to the socio-racial classification “black.” People classified with one of the several mixed socio-racial classifications could have their freedom endangered if their black maternal ancestry was emphasized and not their Indigenous one. Such was the case of the enslaved woman Rosa. In her freedom suit, Rosa tried to achieve her freedom by arguing that she descended from an Indigenous woman, but her master said that she was a cafuza, a descendant of an enslaved black woman. In that moment of structural economic changes and when several plaintiffs were seeking freedom by asserting their Indigeneity in local courts, settlers developed vernacular practices that entrenched the racial lines of slavery. Other written documents, such as manumission letters, demonstrate that those vernacular practices transferred into notarial language. By emphasizing the black ancestry of subjugated people, notaries could, in effect, legitimate their enslavement and hinder possible legal actions.

The article is divided into four parts. The first part explores the transformation experienced by Maranhão's society in the mid-eighteenth century, when the region transitioned from a frontier economy based on cattle ranching to cotton and rice plantations. The next two sections discuss the relations of dependency engendered between Indigenous workers and their masters. The strategic use of the category “índio” could limit their exploitation and create spaces of autonomy. The final part is lengthy and discusses every step of Rosa's freedom suit to understand the impacts of the transatlantic slave trade in the management of slavery and the post-abolition of Indigenous enslavement. The case illustrates the limits of the strategic use of the category índio.

Maranhão, 1740s–1790s

The city of São Luís, founded by French explorers in 1612 and conquered by the Portuguese in 1615, sits on an island on the Atlantic coast. The Bay of São Marcos and the Bay of São José separate the island from the continent, and they are both home to two important satellite settlements; respectively, Alcântara and Icatu. Despite fierce resistance from autonomous Indigenous groups on the continent, Portuguese settlers and Catholic missionaries founded forts, villages, missions, farms, and several ranches along the three main rivers that flow from the interior: the Itapecuru, the Mearim, and the Munim. São Luís was the capital of the State of Maranhão (created in 1621), home to the governor, and the official seat of the Bishopric (created in 1677). In practice, the Bishopric of Maranhão functioned most of the time without a bishop, and the governor spent more time in the city of Belém, located further north and strategically positioned to control the mouth of the Amazon River.

Despite its official status as capital, São Luís did not have a sizable population until the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Atlantic currents isolated São Luís from the main Luso-Brazilian commercial maritime routes in the South Atlantic. The city's population certainly did not exceed 15,000 people in the 1750s.Footnote 19 The urban footprint was limited to a few streets, and the only prominent buildings were Catholic churches and convents. The houses of most settlers were rustic and modest whitewashed mud constructions, and reference to more sturdy constructions was rare.

People living in the city dedicated their time to several artisanal activities, such as carpentry, masonry, blacksmithing, and petty commerce. Many women worked as washerwomen and many men worked as fishermen. Soldiers also accounted for a significant part of the population. Members of the elite had at least one house in the city and farms and ranches around it. Economic activities developed in the countryside created employment opportunities back in the city. Indigenous workers transported cattle from the interior to the coast in canoes through riverine paths.Footnote 20 Indigenous journeymen also worked in tanneries. Settlers in São Luís harvested sugar cane to manufacture aguardente,Footnote 21 rather than sugar. Aguardente was widely consumed in the city taverns and played a decisive role in commercial relations with Native peoples.Footnote 22 São Luís became a bustling port city only in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, with the intensification of the transatlantic slave trade and the rise of cotton and rice plantations.

Sometime in the 1740s and 50s, however, Maranhão became a frontier economy based largely on cattle ranching, the production of manioc, aguardente, and cotton. In the mid-eighteenth century, the region counted 448 ranches spread along the rivers and going deep into the interior.Footnote 23 Manioc was the main staple in the local diet and was widely cultivated. Aguardente was consumed in the city and was key to negotiations with Indigenous groups. Indigenous women harvested and weaved cotton to make homespun cloth. Cotton rolls (rolos de algodão) were the primary currency in a region where the circulation of metallic money was scarce. Prices were fixed in cotton rolls, including commercial transactions, contracts auctioned by the Municipal Council, and the payment of Indigenous labor. Indigenous workers, enslaved or not, made possible all these activities.

From São Luís, there were two frontiers of Indigenous enslavement and labor recruitment. The first was the savannah in Maranhão, where settlers clashed violently with autonomous Native groups. By the mid-eighteenth century, Indigenous Gê-speaking groups, such as the Timbira, were systematically imprisoned in “just wars” declared by the Portuguese crown. The bulk of São Luís's workforce, however, was captured in the Transamazonic slave trade. By the 1730s–40s, Portuguese slave raiding expeditions were reaching as far as the Upper Negro River and the Branco River. Settlers relied on two modes of labor conscriptions: privately financed resettlement of free Indigenous people, the descimentos, and slave expeditions, which were private or state financed, the tropas de resgate. These modes of labor recruitment incorporated Indigenous workers with different legal statuses in colonial settlements. Indigenous workers conscripted on descimentos were free. Indigenous workers captured in “just wars” and tropas de resgates were slaves. Once settled in masters’ houses, farms, and ranches, the lines between free and enslaved Indigenous workers were far from clear.

Imperial reforms in the second half of the eighteenth century hardened the racial lines of slavery. The reforms attempted to regain control over the territories, resources, and subjects under the aegis of the Portuguese crown. The reformers projected the incorporation of “rustic peripheries,” to enhance the extraction of natural resources and produce increased revenue through taxation.Footnote 24 During this period, two new forces emerged in Maranhão and changed the landscape of enslavement: the creation of a monopolistic trading company and the new Indigenous policy to claim possession of territories in dispute with Spain.

If Indigenous workers interacted with a limited number of Africans in the previous years, the port of São Luís saw constant arrival of slave ships after the 1760s. The trading company (Companhia de Comércio do Grão-Pará e Maranhão) founded in the 1750s transported African slaves and fueled the development of cotton and rice farms in São Luís's hinterlands. Between 1751 and 1787, Maranhão received 22,414 African slaves, drastically contrasting with the earlier period, when only roughly 3,368 African disembarked there.Footnote 25 Cotton, leather, and, later, rice exports rapidly took off. Trading balances before the 1750s reported hides as the only product worth mentioning and did not account for a single bag of rice exported. In the following decades, rice and cotton industries would achieve staggering levels of production, and in the last two decades of the eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, Maranhão's cotton would supply an important share of Britain's demand.Footnote 26

Concomitantly, imperial reformers idealized new ways to incorporate Indigenous peoples into the empire. Indigenous Americans were one of the cornerstones in the border disputes, because Iberians considered territories occupied by Indigenous allies to be their own.Footnote 27 After the publication of the 1755 abolition law, the Portuguese crown enacted the Diretório dos índios (1757), a body of rules regulating the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the colonial order. As another historian described it, the Portuguese imagined a project to “Occidentalize” Indigenous people.Footnote 28 Old religious missions were renamed after Portuguese cities, but the transformation went well beyond a matter of nomenclature. From that moment on, Indigenous people were eligible for posts in the civil administration and the villagers’ administrators imposed the Portuguese language and encouraged intermarriage with Portuguese. More importantly, the colonial state closely regulated labor exploitation, guaranteeing a source of workforce for royal services, such as the demarcation expeditions, the canoe journey connecting the mines in Mato Grosso to the Atlantic, and naval construction. Several Portuguese-like polities emerged in the Amazon region, serving as proof of Portuguese possession of the main rivers, and helping to recruit autonomous Indigenous groups in the interior.

The Portuguese crown designed a new imperial policy for Indigenous subjects centered on the frontiers. Within colonial settlements, however, where thousands of Indigenous workers lived in bondage, the adaptations to the local situations and customs prevailed.

The Law of June 6, 1755

This section first discusses the law of June 6, 1755, and the development of the category “índio(a) de soldada,” freed índios(as) who worked for a settler in exchange for a payment. Then, it explores why and how Indigenous workers attempted to stay or to move away from settlers’ households. These endeavors depended on elements such as honor, ritual kinship, intimacy, sex, and autonomy. Reconstructing these stories sheds light on the conflicts and conciliations that underpinned the transition from one legal status—slave—to the other—índio de soldada.

The law of June 6 1755 reinvigorated several aspects of previous Portuguese laws and policies, in particular their positions on Indigenous freedom, Indigenous possession of property, and the payment of Indigenous labor.Footnote 29 Returning to three laws from the seventeenth century, the 1755 abolition law stressed the unconditional freedom of Indigenous peoples.Footnote 30 Consequently, it revoked traditional practices that enabled the enslavement of thousands of Indigenous Americans throughout the seventeenth and first half of eighteenth centuries, such as the tropas de resgate, authorized and systematized in the alvará of 1688. The law reinforced points already present in the law of April 1 1680 on Indigenous peoples’ possession of property and land, which guaranteed their legitimate possession over their farms against settlers’ encroachment, and prohibited forced relocations. Finally, wages for Indigenous labor were a matter of intense debate, and attempts to regulate payments date back to the mid-seventeenth century and continued throughout the colonial period.Footnote 31

The 1755 abolition law was published in Maranhão on May 8, 1757, 2 years after its original enactment. The correspondence between the Governor Francisco Xavier Mendonça Furtado and his brother, the Marquis of Pombal, helps explain the almost 2-year delay. First, it was indispensable that settlers would have access to enslaved African labor. After all, the broader reformist project aimed at the colonies’ economic growth and enslaved labor was crucial. Second, after spending a few years in the region, Furtado understood that limiting settlers’ dominion over their Indigenous workers was a sensitive subject. “In this state,” Furtado wrote in 1751, “a rich man is not one with much land, but one with the greatest quantity of Indians, [who are used] both for agriculture and for the extraction of forest spices.”Footnote 32

Shortly after the publication of the “law of liberties,” the Governors of both Maranhão and Grão-Pará issued orders (bandos) allowing settlers to keep their former Indigenous slaves in their households, if it was a consensual arrangement and they were paid. This arrangement was known as soldada.Footnote 33 Portuguese authorities feared that once the slaves knew about the content of the law, they would immediately escape to the interior. The order authorized masters to keep the Indigenous workers who “customarily serve them, and because of that are in their farms and houses, working the land and serving in the same houses,” and it requested the masters to present records of the Indigenous workers serving them within 2 months. In practice, the order implicitly legitimized thousands of previous slave raids in the interior and allowed the continuation of customary labor arrangements almost indistinguishable from slavery.

Wills (testamentos) and baptismal records demonstrate that settlers and colonial officials understood the abolition law of 1755 in relation to customary labor arrangements. Settlers identified the Indigenous workers who used to serve them (or were still serving them).Footnote 34 Inês São José's will, from 1758, illustrates this process. She declared ownership not only of herds of cattle in Pastos Bons but also of sixteen slaves, “legitimate slaves of the Guinea Nation.” One índio, however, suggestively named João das Missões from the city of Pará, was declared as her legitimate slave whom she had bought and kept in her company, “but because he is covered by this new law of His Most Faithful Majesty, I keep him by paying him a salary until another resolution.”Footnote 35

Inês São José was not the only one who was expecting a new resolution from the king and settlers were better off registering their slaves and former slaves. Years after the publication of the 1755 law, priests were still recording those “freed by the law.” In the Chapel of Senhora Santa Ana, the priest Domingos Barbosa baptized Maria in July 1768. Maria's mother was Luzia, “who used to serve Valério Fonseca freed by the law.” Maria's godmother was Felizarda, a free índia from São Luís.Footnote 36 It is difficult to assess what was the relationship between Luzia/Maria and her former master, Valério Fonseca. In other cases, the priest recorded that the Indigenous worker was still living under the former master's roof. Mariana, for example, baptized her daughter Barbara in November 1752. She appeared as one of the servas (serf/servant) of Clara Peregrina's household.Footnote 37 Six years later, in March 1758, she went to the Sé Church to baptize her son, Francisco Xavier. Here, the priest recorded Mariana as “freed by the law, living in the house of Clara Peregrina.”Footnote 38

The way that the priests were recording Indigenous workers, explicitly referring to their former masters, suggests that the master/slave bond was a form of identification within the community and that there was public acknowledgement of customary labor arrangements. Moreover, contrary to what colonial officials imagined, Indigenous workers did not vanish from the city and farms. Instead, according to parish records, they were very much part of the community in which they were raised, attended the church, married, and worked.

Into the Households and Lives in Bondage

Last wills and baptismal records reveal Indigenous workers’ subordinate position within households as well as deeper aspects of their relationship with their patrons. These close ties involved ritual kinship, honor, intimacy, and sex. Settlers frequently used ritual kinship (compadrio) as an excuse to keep Indigenous workers in their households. For instance, when Baltazar Neves drafted his will in 1755, he declared that “all the slaves that are heathens of the land [do gentio da terra] that I possessed are my legitimate slaves and I have their registers, only [with regard to] Domingos I do not possess registers. [He] will stay in the company of his godfather, my son, Father Alexandre Pedro.”Footnote 39 As thousands of other Indigenous workers in São Luís, Domingos was probably captured in an unofficial slave raid in the interior, since Neves did not have documents proving his legitimate enslavement. Nevertheless, if a monetary value was not assigned to them, São Luís's settlers bequeathed these workers to their heirs based on the bonds of compadrio and the dependencies within the household.Footnote 40

The publication of the abolition law of 1755 complicated the situation for settlers, and they commonly petitioned to the authorities requesting exception from the application of the law. Dona Ana Catanhede, of Alcantâra, relied on notions of honor, widowhood, and the common theme of poverty to request to keep her índios in her household, despite the new law. Three points sustained her argument. First, she claimed that she had lived “honorably and honestly” with her husband, António Martins Vieira, until his death. Second, after her husband's death, she had lived in poverty and did not have a single slave to serve her, “not even to wash her shirts, or to carry a pot of water for her to drink, or any other service.” Finally, the few slaves that she had “were included in the law of liberties.” The cafuza Antónia was an exception, and stayed in her house. Antónia and Ana developed a long-term affectionate bond since Antónia was born in captivity and raised in Ana's house. Over the years, Antónia gave birth to several children. Ana Catanhede raised them in her household, despite her poverty, “with nobody's help, except God's.” In her justificação,Footnote 41 Ana Catanhede mobilized three witnesses to testify in her favor. They all confirmed Ana Catanhede's pious and modest way of living. More importantly, they all confirmed the personal ties that entwined patron and Indigenous workers within the household. Considering the evidence produced by Ana Catanhede's justificação, her request was granted.Footnote 42

Father Angelo de São Alberto from the Carmo Convent also desired to retain his índios in his household. Although after his mother's death he inherited one índia, called Dionísia, his convent kept the índia for their services. Dionísia had had six children, of which four had died before father Angelo's arrival. João was already in his possession, but Bonifácio was laboring for one of the convent's farms. Father Angelo argued that because Bonifácio's mother “was seized in a descimento that Your Majesty conceded to my father,” he had the right to enjoy his services. He argued that not only were they his servants, but that also their assistance was much needed given his poor health and the fact that without them “I have to go to the kitchen by myself and serve myself with my own hands.”Footnote 43 Like Ana Catanhede, father Angelo relied on customary practice to exploit Indigenous labor, even when their enslavement was questionable. Indigenous workers recruited from descimentos were considered free workers, at least in theory. These masters’ pleas to keep their customary workers within their control reveal the importance of their labor for the reproduction of settlers’ households. As honorable members of the community, they felt they should not engage in menial labor, and expected the crown to do justice by not disrupting that order of things.

Indigenous workers themselves also fought to remain in their customary labor arrangement. For instance, in 1784, the índio Joaquim José, of São Luís, petitioned queen Maria to stay in the household of Domiciano José de Moraes. According to him, he had lived for many years in that house. Moraes's wife had raised him and was his godmother, “always treating him with love.” The labor arrangement was made after the publication of the 1755 abolition law. Joaquim José sought to remain working for his former master who would compensate him with the customary salary for Indigenous workers. Domiciano Moraes requested an official order (portaria) from the governor to make sure that he would not have problems in the future, probably protecting himself from potential expensive judicial battles. The governor, however, according to Joaquim José, took him out of Moraes's house and drafted him to work for Francisco Salerio, who “treated him worse than a slave, beating on him without any reason.” The petition builds on the laws that guaranteed Indigenous freedom and on other decisions made by the queen allowing Indigenous workers to remain under their customary labor arrangement.Footnote 44

Sexual relationships also played a part in labor arrangements. Several cases of an illicit sexual relationship between settlers and Indigenous women survived in the records of Maranhão's Ecclesiastical Court.Footnote 45 In 1781, Miguel Maciel Aranha denounced the couple António Costa and the índia Apolônia for living together without being married. They were living in their house in the Ribeira do Itapecuru, not far from the city of São Luís, and, therefore, were still under the gaze of the Catholic church. Despite the accusation of maintaining a relationship outside of marriage, António Costa requested the governor's written orders (portaria) to keep Apolônia in his house, and promised the payment of a salary.

Governors issued hundreds of orders drafting Indigenous workers to work for specific settlers for a specified time. The archive for those lists is extremely limited for Maranhão. The only list that I found enumerates several Indigenous workers and their patrons. In the column where it should specify the number of months of service, it says “without limitation of time.”Footnote 46 At a glance, this would be additional evidence of how settlers worked the system to maintain Indigenous workers within their households. Without discarding that possibility, I suggest that remaining indefinitely under settlers’ roofs could benefit the interests of Indigenous workers.Footnote 47

Apolônia probably preferred to remain under the roof of her companion, instead of risking being conscripted for some difficult work, such as farming in a distant land, or being selected to perform domestic labor for a potentially cruel new patron. It is difficult to determine if the relationship was abusive or not. Reading the witnesses’ accounts, however, an image of a stable and long-term relationship emerges. All the witnesses confirmed the accusation that António had asked the governor—by issuing an order—to keep Apolônia in his house, with payment (soldada). All the witnesses also said in rather contradictory terms that António kept Apolônia “hidden” in his house, but that everyone in the community knew that. In his deposition, José Malheiros revealed that one day he saw Apolônia carrying water in his backyard going back to António's. At the end, the vicar-general lightly punished the couple. They had to go before the vicar and sign the terms of punishment. Moreover, they had to pay a small fine and the costs of the investigation (4$895 réis).

Although the examples narrated portray a peaceful image of the relationship between masters and Indigenous workers, there were cases of conflict, particularly when Indigenous workers wanted to move away from their masters and loosen the ties of dependency. The petitions and litigations of Indigenous workers challenge claims of imperial officials. They were not lazy vagabonds and indomitable workers who needed the tutelage of settlers to tame their lives. Their efforts to loosen the ties of dependency could be related to their desire for mobility and independence. The case of índio Bernardo demonstrates what could happen when Indigenous workers decided to sever their customary labor arrangements.

In 1770, António Cavalcanti, a planter from Maranhão, petitioned the king for a 10-year extension to pay his massive debts. Cavalcanti identified himself as a nobleman, married to a noblewoman, and head of a distinguished family of São Luís. Although he had possessed some rural estates and lived honorably with his wife and their several sons and daughters, he saw himself without means to afford his family's significant expenses. The reason for his bankruptcy and disgrace was solely the abolition of Indigenous slavery in 1755. In his justificação, he mobilized four witnesses who confirmed his noble status and the downfall he had suffered with the abolition of Indigenous slavery.Footnote 48

Regardless of the truth of António Cavalcanti's story, 9 years before his petition, in 1761, he was involved in a litigation against the freed mulata Úrsula Boavida. Úrsula initiated the litigation in April 1761. According to her, she was a freed woman, the former slave of Marcos Boavida and the priest Pedro Correia, who lived in the Ribeira do Itapecuru. The conflict did not involve her, but her husband, the índio Bernardo, with whom she had been married for 30 years.Footnote 49 Pedro Correia also kept Bernardo as a slave. Later, Correia transferred Bernardo to Cavalcanti. Bernardo achieved his manumission after the publication of the law but kept serving Cavalcanti's household as a fisherman. According to Úrsula, Bernardo's payments were no longer to his satisfaction, and he wanted to live with his wife in the Ribeira do Itapecuru because “according to the law of liberties [law of June 6 1755], índios can freely live their lives; they can serve whoever pays them a better salary, and nobody can force them otherwise.”Footnote 50

In around 1760, Bernardo was spending more time in the Ribeira do Itapecuru than in São Luís. The physical distance from his servant did not please Cavalcanti. Upon knowing about the legal case, he argued that the ecclesiastical justice could not overrule the labor contract that he had arranged and that was confirmed by the governor (secular justice). This potential conflict of jurisdiction would represent insecurity for settlers because “we would not have people to row the canoes transporting cattle and other services essential to us.”Footnote 51 Besides the potential jurisdiction conflict, Cavalcanti's defense articulated three other points: the legal status of Úrsula, the place of the couple's residence, and his noble status.

Úrsula justified her presence in the Ribeira do Itapecuru because of her obligations for the chapel instituted by her previous owner. Cavalcanti argued that she was freed by prescription and had been living as a freed woman for years. Moreover, Cavalcanti accused the couple of lying about their permanent move to the Ribeira do Itapecuru. Úrsula and Bernardo were living for more than two decades in a house in Cavalcanti's backyard in Desterro Street. Úrsula was a well-known washerwoman at the public fountain offering her services to several people in the city. Finally, Cavalcanti was a nobleman, married to a noblewoman, a member of the Municipal Council who needed his “servants.” Cavalcanti argued that the justice should not only keep Bernardo as his fisherman, but also conscript Úrsula to his service because she is a “freed black of servile status.” While working for Cavalcanti, she would not have time to come up with false claims and cause disquiet.Footnote 52

The justice wanted to settle the legal status of Úrsula, and requested a copy of Marcos Boavida's will. The outcome of the case is unclear. The conflict could have been solved by other means than judicial intervention or the papers may not have survived. Nevertheless, the short story of António Cavalcanti and his Indigenous servants demonstrate the centrality of Indigenous labor in settlers’ households, and how these settlers could react when their Indigenous laborers tried to leave their control.

Seeking autonomy did not necessarily involve moving away from the city. One could achieve freedom by maintaining their own house and working for wages. Índia Ana Cordeira, for instance, of São Luís, said that although “she was living in her own house,” the governor had drafted her to serve the settler José Araújo in the occupation of “washerwoman and seamstress.” Significantly, Ana Cordeira said that she had served Araújo for 1 year and 7 months from her own house, and that he did not “sustain her or help her when she was sick.”Footnote 53

Contrary to her expectations, José Araújo did not pay for her services. Araújo had only sent $10 réis to buy indigo and gum to iron his clothes. Cordeira complained that such small value was not enough to buy supplies to starch all his clothes. Instead of sending more money or indigo and gum, Araújo sent more clothes for Ana to sew: two skirts. In the meantime, Araújo requested the rest of his clothes back. Cordeira responded that she was still taking care of them.

The índia Ana Cordeira's response enraged Araújo, who started to complain to the governor about her behavior. Without a clear justification, the governor ordered Ana to prison. After she had been there several nights, the governor sent her late one night to the village of Guimarães to work on the farm of José Marcelino Nunes. The long distance between Guimarães and São Luís prevented her from demanding the satisfaction of more than 1 year's worth of work. Staying out of the city, Araújo and Nunes placed a new washerwoman and seamstress at índia Ana's house.

Ana Cordeira, “a miserable helpless índia,” based on the law of June 6, 1755, pleaded the queen to order the juiz dos órfãos Footnote 54 to charge Araújo and Nunes for her services and, more importantly, restore her house in the city. The queen responded that the crown judge (ouvidor) should promptly act on Ana's case, and that if what índia Ana alleged in her petition was true, she should regain her house and receive the payment for her labor.

These fragments of individual stories demonstrate the use of the status “índio” among workers in eighteenth-century São Luís. Indigenous workers understood that the legal recognition of their freedom had constraints in daily life. They also understood that as publicly recognized índios, they could enjoy some rights. As the next section will reveal, being acknowledged in the community as an índio(a) could be the difference between freedom and slavery.

“My Legitimate Slave, a Legitimate Descendent of a Black Slave”: Rosa's Freedom Suit

Rosa was born in the household of one the most prominent settlers of São Luís, Domingos da Rocha Araújo. Araújo was commonly referred as “Captain,” indicating that he had a military position in the local militia, a typical social distinction among the local elites in colonial Brazil. As was also characteristic of the local elites in colonial Brazil, Captain Araújo controlled vast swaths of land, where he raised cattle and cotton destined for the European market.Footnote 55 Domingos Araújo was from Barcelos, Northern Portugal, the son of João Rocha and Brígida Araújo. He probably migrated to Maranhão as a young adult, and on July 16, 1744, he married Cecília Costa, daughter of Gabriel Costa and Margarida Coelha, members of the local elite.Footnote 56

The strategic marriage was Domingos Araújo's first step to establish himself as a key figure in the community. He lived with Cecília Costa in the Poço Velho Street, just a few blocks from other important settlers, such as Pedro Lamaignere, Lourenço Belfort, and António Gomes Souza. As did many other landowners, he served several times in the local government, the Municipal Council.Footnote 57 Besides his participation in the local politics, he often served as godfather to São Luís settlers’ sons and daughters. On January 18, 1762, Domingos Araújo and Maria Josefa appeared as Paulo's godparents. Paulo was the son of Francisco António Domingues and Maria Josefa Cabessa. Just like Araújo, Domingues possessed many slaves, and was involved in the cotton export economy. They even negotiated some urban properties in the 1760s.Footnote 58 Araújo's broad compadrio network extended to the enslaved population. He was the godfather of some slaves of other members of the local elite, such as Ana, slave of Clara Peregrina.Footnote 59 More significantly, Araújo was the godfather of Indigenous workers incorporated into his household. On December 29, 1767, the “índios of the Nation Timbira” Frutuoso, Bernardino, and Ana were baptized in the Sé Church of São Luís. They were all children, “from the house of Captain Domingos Araújo,” who also appeared as their godfather.Footnote 60

Although I have never found a will or an inventory drafted by Captain Araújo, his wife notarized one. In her will, written in 1760, Cecília Costa donated a substantial amount of money to Catholic institutions, such as the Church of Nossa Senhora do Rosário and the Santa Casa da Misericórdia. She also distributed money to nieces and nephews. The will listed seven slaves: Venceslau, son of the cafuza Ivana, and the mulata Maria, mother of Domingos and Claudina. The enslaved women Angélica and Rosa completed the list. Cecilia Costa had inherited some of those slaves from her father, meaning that they had been enslaved in the family for decades.Footnote 61

Yet, her will did not portray the diverse backgrounds of the household's servants. A quick glance at baptismal and marriage records reveals that Africans and Indigenous workers lived alongside under the roof of Domingos Araújo and Cecília Costa. In addition to the Indigenous workers of the Nation Timbira, their household included other Indigenous slaves, Indigenous freed servants, mixed slaves, and recently arrived enslaved people from Africa. Domingos Araújo and Cecília Costa seem to have played an important role in the incorporation of Native workers in the colonial world. In June 1755, the “índios from the land” Aníbal and Joana married in the Sé Church. They were former slaves of Captain Jeronimo Taloza from the village of Vigia, in Pará. At the time of their marriage, they were “living in the house of Captain Domingos Araújo.” Among the witnesses were António Fula and Felipe, both slaves of Araújo.Footnote 62

Of the slaves specifically mentioned by Cecília Costa in her will, three received conditional manumission. The two men, Venceslau and Domingos, had to remain in the company of her husband until his death. The woman, Claudina, was required to stay with Ana Maria until her last days. In the will, however, key details went unremarked. Some of the slaves were related, Rosa and Venceslau were cousins, for example. And Cecília Costa failed to acknowledge her kinship ties with some of her slaves. There was more tension within her household than her pious will portrayed.

It is difficult to understand why Rosa decided to use colonial law to seek her freedom. The couple Domingos Araújo and Cecília Costa did not have children, and Cecília Costa decided to make Ana Maria, an orphan raised by her in the household, the main beneficiary of her estate, that included the enslaved woman Rosai. In 1769, Ana Maria notarized her will. Ana Maria seemed to have granted the possibility for Rosa to achieve freedom, with Captain Araújo's permission.Footnote 63 From 1769 to 1772, something strained the relationship between Araújo and Rosa, when she asked for legal intervention in the master/slave bond. Curiously, Ana Maria's will was not a point of contention in the litigation. Cecília's, however, was critical.

In the summer of 1772, with the assistance of someone, probably Bernardo da Silva Gatinho, who would later represent her in the litigation, Rosa decided to use a quicker type of litigation (ação sumária), an ação de justificação.Footnote 64 In her justificação, she articulated three interconnected points. The first and most crucial was her genealogy. Rosa was the daughter of Joana and the granddaughter of Micaela. Micaela, in turn, was the daughter of Dionísia, who, finally, was the daughter of Iria, “índia from the Amazon River.” The índia Iria was, then, Rosa's “great great grandmother.” More than stressing her Indigenous ancestry, Rosa emphasized Iria's legal status: she was “free and not subject to any form of captivity.”Footnote 65 Índia Iria was not only legally free, but priest André Lopes always treated her as such in his household, where she used to live. Rosa, thus, should be judged free once she proved that she descended from índia Iria. Finally, the Portuguese monarchs had enacted several laws guaranteeing the freedom of the “índios from this land.” According to natural law, every person must be presumed free, including the descendants of an “American índia.” Those who claimed otherwise—that Rosa was a slave— bore the burden of proof.

The Captain's poor health stalled the freedom suit. His lawyer requested an extension to provide a response. Before challenging the content of Rosa's petition, the Captain's lawyer asked some questions to Rosa. First, why did she recognize Captain Araújo as her legitimate master? Second, why did she wait 15 years to fight for her freedom? The law was published in Maranhão in 1757, and she did not fight for her freedom until 1772. Was she out of town during that period, or was she ignorant about the content of the law? Third, why did the índia Iria end up in slavery? Fourth, if Iria was from the Amazon River, which Indigenous village (aldeia) did she come from? Finally, was she able to name her relatives that were now free?Footnote 66

Rosa's answers to all these questions were simple. She began by saying that she was “free by her nature” and Captain Araújo kept her “unjustly” in slavery. The answer to the second question is more significant. She confessed that she was in town when the law was published, but she did not seek her liberty because Cecília Costa, Captain Araújo's wife, “who had raised her,” asked her to stay in the house serving as slave, with the promise that she would manumit Rosa after her death. The captivity of Rosa's family began a few decades earlier when índia Iria was serving priest André Lopes's household. When the priest died, settlers took advantage of Iria's “ignorance” and divided his slaves among themselves, “because at that time they did enslave índios.” For the final questions, Rosa's lawyer pointed out her inability and lack of obligation to give such information.Footnote 67

Finally, on January 23, 1773, the Captain's representatives offered their version of the story.Footnote 68 The Captain's defense introduced an alternative genealogy for Rosa. The Captain's representative, José dos Santos Freire, articulated fourteen different points. He initially contested Rosa's genealogy, arguing that Rosa did not descend from an índia called Iria, but rather from “a black woman legitimate slave.” Both parties agreed that Rosa was the daughter of Joana, granddaughter of Micaela, and the great-granddaughter of Dionísia. Yet, in the narrative of the Captain, Dionísia “was not the daughter of an índia called Iria, as she [Rosa] says, because the mother of Dionísia was Sabina, a black woman legitimate slave.”

The Captain's defense also introduced a central character to the story, Damazia Costa, the daughter of Dionísia, and, therefore, sister of Rosa's grandmother (Micaela). More importantly, she was the half-sister of her owner, Cecília Costa, an illegitimate daughter of Gabriel Costa with one his slaves. José Freire argued that Rosa's relatives recognized their legitimate enslavement and only achieved their freedom thanks to their masters’ grace, including Damazia Costa. Her case is instructive because she was raised in the household of Captain Araújo and was considered “the most ladina of Rosa's generation.”Footnote 69 Then, if she was the most ladina, she would have known that she had the right to claim freedom based on the new law/Indigenous ancestry. Nevertheless, Damazia went through an ordeal to receive her manumission letter when she wanted to marry a “white man” called José Joaquim. She begged Cecília Costa for her freedom, who tried, unsuccessfully, to convince her husband to sign the manumission letter. Only after many pleas from different people and when his wife was in bed sick did Captain Araújo agree to manumit Damazia Costa.

The alternative narrative offered by the Captain's defense relied on two additional important points. They emphasized the legitimate enslavement of Rosa's family by insisting that her relatives recognized their slave status. The ones that were freed achieved such status by the grace of their masters and not for being descendants of índias. Moreover, contrary to what Rosa argued, Cecília Costa's will was very clear on Rosa's legal status: she was transmitted to her heir, Ana Maria. Finally, they deny the existence of an índia Iria in the household of priest André Lopes.

After recovering the Captain's account, the parties had 10 days to collect witnesses’ depositions. Each party mobilized witnesses who would tell their versions of the story to a justice official. While Rosa's witnesses had to respond to the three points raised in her justificação, the ones mobilized by the Captain responded to the fourteen points he made. The different social statuses of the witnesses mobilized by each party reveal the power imbalance in this judicial struggle. Eight women testified on Rosa's side, of which five were freed women, and five men, most of them from the plebeian classes, including a weaver, a soldier, and peasants. Captain Araújo mobilized nine men and five women, most from the local elite.

Witnesses on Rosa's side did not deny her Indigenous ancestry, but most of them were ignorant about who was the mother of Dionísia. Hipólito Souza and Narcisa Conceição were exceptions. On January 25, 1773, Hipólito Souza, an 81-year-old man, remembered that he knew Iria, from the household of priest André Lopes. According to him, Lopes gave Iria to his sister, Margarida Coelha, wife of Gabriel Costa and father of Cecília Costa. However, Iria was transmitted not as a slave but “to assist in the raising of her children.” Narcisa Conceição, a freed woman, also remembered índia Iria, whom she met in her youth. Narcisa confirmed the genealogy advanced by Rosa and included a phenotypical assessment of Iria's Indigenous origin: she knew that she was an índia because “she could see that she was an índia from her land.”Footnote 70

Damazia Costa, the freed woman raised in the household of Captain Araújo and Cecília Costa, testified on Rosa's side. She confessed that she was the daughter of Dionísia and half-sister of Cecília Costa. This fact probably explains why Damazia was raised in the household and then considered the “most ladina of her generation.” It could also explain some tensions between her and her half-sister, Cecília Costa. Contrary to what the Captain's defense argued, Cecília Costa opposed her marriage with José Joaquim, and publicly said that she was an enslaved woman. Damazia was adamant about her decision to marry, and threatened to “get her papers to show her freed status.” Such attitude enraged her half-sister who bemoaned “that Damazia did not give her another regret.”Footnote 71 In her deposition, although she confessed that she did not know the origin of her grandmother, she had heard from her brother that their mother was an índia called Iria. Also from hearsay, she testified that the very Margarida Coelha, wife of Gabriel Costa, had told that “Damazia's mother, Dionísia, descended from an índia, and the said Dionísia was transmitted to her [Margarida Coelha] by her brother, the priest André Lopes.”

On the Captain's side, most witnesses confirmed his version of Rosa's genealogy. Apolinário da Costa, a 71-year-old tailor who lived in the Ribeira do Itapecuru, went to the clerk's office to give his deposition. Like Damazia, Apolinário was the half-brother of Cecília Costa, and another bastard son of Gabriel Costa. He confessed that he was raised in the same household and knew Rosa's entire family. After repeating the same genealogy, Apolinário said that “Dionísia was the daughter of Sabina, a black woman and legitimate slave.”Footnote 72

The Captain's witnesses also agreed on the story of Damazia Costa marriage with the “white man” José Joaquim and the existence of an índia Iria in the house of priest André Lopes. The crucial point to prove about Damazia was that she married Joaquim after the publication of the 1755 law, and that therefore, she was freed by the grace of her mistress, and not by the benefit of that abolition law. Regarding the assets of priest André Lopes, it was important to establish that he bequeathed them to his sister, and not to Captain Araújo.

Rumors, whispers, and gossip circulated among plebeian and elite populations. Several witnesses gave their account about one episode that happened inside the house of Captain Araújo and Cecília Costa. In around March 1769, when Cecília was sick, she started hearing rumors that their slaves were saying in the city that they were freed. As many witnesses narrated the episode in their depositions, the couple gathered some slaves and questioned them about these inconvenient rumors. Some witnesses recounted this story by hearsay, others claimed to be present. Such was the case of Maria Coelha, a 40-year-old married woman from Nova Street. Maria reported to Cecília Costa that some of Rosa's relatives were saying “behind Cecília Costa's back” that they were freed. “They were her legitimate slave,” Cecília Costa confidently replied, “because they descend from a black female slave, and they were always seen as such.” Maria added in her deposition that she had seen the Captain calling two of those slaves. After asking them about the rumors, both slaves denied the rumors, according to Maria Coelha.Footnote 73

Both parties had difficulty including witnesses. On Rosa's side, the official initially refused to collect the deposition of Estácia Souza. The official argued that she was an enslaved woman and disqualified to testify in the case. Bernardo Gatinho convinced the crown judge (ouvidor) to include Estácia Souza in the case, given the fact that she was freed by prescription. Some of the Captain's witnesses were not in the city, and he requested a letter of inquiry (carta de inquirição) to collect three witnesses’ depositions in the Ribeira do Mearim. One of them was an enslaved man, and the Captain requested authorization beforehand to include his knowledge of Rosa's genealogy in the legal case file.

In the Ribeira do Mearim, Rosa and her family were described by the official Bernardo Gomes Pereira as cafuzas, descendants of a maternal black lineage. The three witnesses who testified were old enough to have known Rosa's descendants. They were from a diverse social spectrum, ranging from a slave to a Captain. Both Captain Jerônimo da Gama, who was the neighbor of Gabriel Costa, and the slave Bruno da Costa, who was raised with Rosa in the same household, confirmed that the cafuza Rosa did not descend from índia Iria. Only the third witness, the widow Ana Correia, explicitly said that the “mother of Dionísia was called Sabina, a legitimate black slave.”Footnote 74

After the inclusion of the witnesses’ depositions in the legal file, both parties delivered a written defense. Bernardo Gatinho produced a lengthy written legal argument to defend Rosa's free status. He made two main points: the presumption of freedom and the quality of the testimonies produced by the Captain. Gatinho argued that Rosa wanted to “use” her liberty and the Captain would not allow. Índios(as) were free people in the Portuguese empire according to several laws, particularly the law of June 6, 1755. Freedom was considered a natural condition, and it required proofs to keep a person in captivity. Even if Rosa descended from cafuzas, the Captain had to prove that the “mixing black blood came from maternal line.”Footnote 75 Most of the witnesses knew about the case from hearsay and not direct experience. Several others had heard important information from Cecília Costa, which was not appropriate because she had a vested interest in the case.

Captain Araújo's defense also emphasized problems with the witnesses mobilized by Rosa. José Freire, who penned the defense, argued that the only witness produced by Rosa worth credit was Izabel Coelha Silva, a “white woman.” And yet, Silva did not know if Rosa descended from an índia or a black mother. The rest of the witnesses were from the plebeian classes, he argued, and not worth attention.Footnote 76

Yet, the strongest part of Araújo's defense gravitated toward the scope of the law of June 6, 1755. The norm clearly excluded African and African descendant slaves. “The law of liberties of June 6, 1755, is not so universal,” wrote José Freire, “that it also extends to descendants of black slaves, but it excepts these and keep them in their legitimate captivity.”Footnote 77 Concrete cases would generate some questions as to whether a person descended from blacks or índias. In those cases, their reputation would be critical. “It is enough that they look like an índio(a) to be reputed as such,” wrote José Freire, but this would not apply to Rosa because “neither in her color, nor in her hair, [she] looks like an índia.” In those cases, a visual inspection could be requested, but it was not necessary in the case at hand, “because her color and her hair demonstrate her black origin, and the enslavement of those are ratified by the Monarch in the said law.”Footnote 78

Freire decided to request four additional documents to further the Captain's case: first, a written request from the priest, Bernardo Bequimão, to attest that some of Rosa's witnesses were not part of the Catholic congregation; second, a written proof that Maria Coelha, the sister of priest André Lopes, was his only heir; third, a written proof signed by fray João de Santa Tereza saying that he was present when Cecília Costa was sick and asked her husband to sign Damazia Costa's manumission; and fourth, a copy of the part of Cecília Costa's will indicating Rosa's legal status.Footnote 79

After the exposition of the case, the collection of witnesses, the written defenses of each party, and the inclusion of written evidence, Rosa requested the ouvidor to send the legal case file to the Board of Missions for a decision and stated that “any delay would be detrimental to her because she is in the yoke of slavery.”Footnote 80 The Board of Missions, on June 15, 1774, expressed Rosa's fate in a laconic fashion. After repeating the genealogical version of Captain Aráujo, in which Rosa was descended from the black Sabina, and reaffirming that the 1755 law could not be extended in any case to blacks, they condemned Rosa to be “held in the hands of the defendant [Captain Araújo], as her rightful master.”Footnote 81

After the frustrating decision from the Board of Missions, Rosa still had a glimmer of hope and decided to appeal to a superior court. Following the 1755 law, Bernardo da Silva Gatinho sent the case to the Mesa da Consciência e Ordens, a tribunal in Lisbon.Footnote 82 It is difficult to understand the relationship between Rosa and her master during the 2 years in which the litigation occurred in São Luís. When Bernardo da Silva Gatinho appealed to the superior tribunal, he visited Rosa in Captain Araújo's house, which means that she was still living there. On July 25, 1775, 1 year after the Board of Missions’ decision, the case file arrived in the Mesa da Consciência e Ordens.Footnote 83 Sadly, that is all I know about Rosa's attempt to achieve her freedom.

Rosa's case reveals the use of socio-racial classifications to reinforce slavery. When the enslavement of Indigenous people was no longer legitimate, settlers and colonial documents inscribed alternative genealogies emphasizing mixed or black maternal origin. Working people in São Luís shared understanding of their neighbors’ genealogy and reputation. This knowledge was crucial in a moment of transformation in Maranhão's socioeconomic structure. These communication networks disseminated legal knowledge that guaranteed the freedom of descendants of Indigenous mothers. In a region that relied on Indigenous enslavement for decades, many people could viably claim Indigenous ancestry.

Yet, to be reputed as índio(a) was not a given; one had to activate that status. The new norm opened the possibility for massive emancipation of slaves and disruption of the status quo. Therefore, masters reacted by hardening slavery's racial lines. Serial analysis of manumission letters illuminates vernacular practices stressing the black maternal origin of slaves.

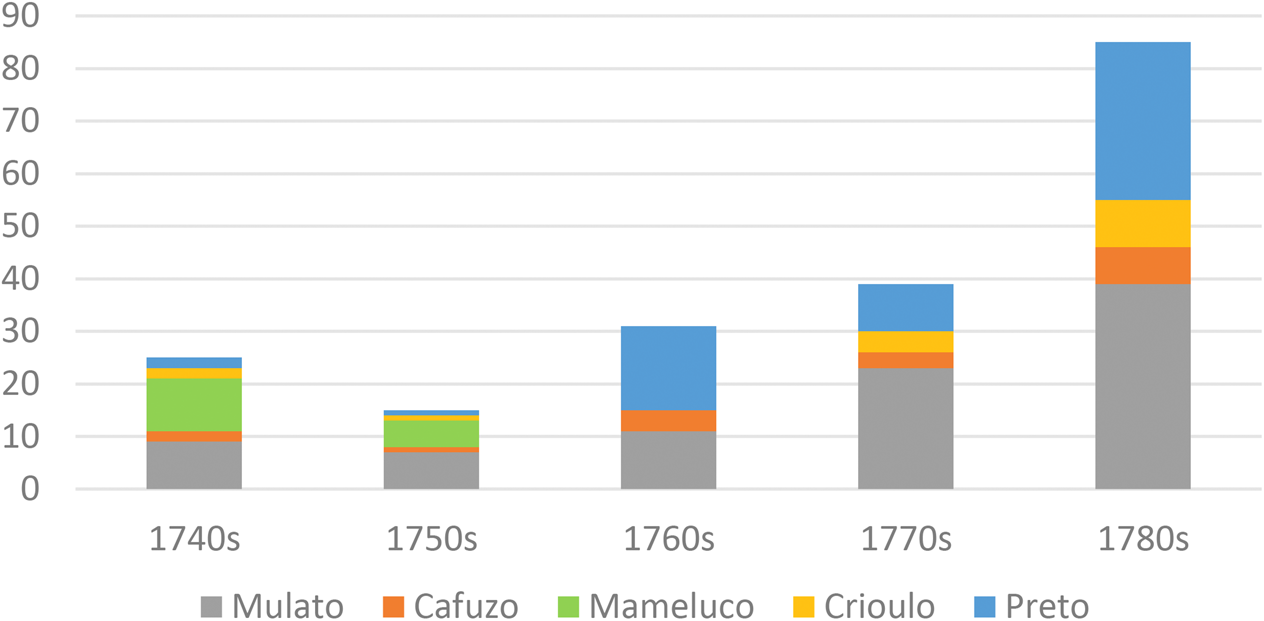

Manumission letters registered in São Luís's notary public from the 1740s to the 1780s demonstrate the consistent use of socio-racial classifications by notaries.Footnote 84 Over time, classifications utilized to describe manumitted people reveal local adaptations to the transition from Indigenous enslavement to the mass arrival of enslaved Africans. Maranhão's notaries employed five main socio-racial classifications: mulato, cafuzo, mameluco, crioulo, and preto. The intensification of the transatlantic slave trade to the region explains the increasing number of pretos (blacks). Surprisingly, cafuzo, one of the most common classifications in other types of sources, such as baptismal records, was not recurrent (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Socio-racial classification of manumitted slaves in São Luís, 1740s–80s.

The contrast between mameluco and mulato reveals the transformations of Maranhão's slavery. The data suggest the progressive abandonment of the classification mameluco after the 1750s, even if I include one manumission letter that specifically labeled the slave as “from the heathen of the land” (do gentio da terra), a classification used for Indigenous Americans. From the master's point of view, it makes sense that the term mameluco would virtually disappear after 1755 because the term was associated with Indigenous ancestry. Although the term mulato appears in the 1740s and 1750s, its prominence in the following decades suggests two conclusions. First, the constant influx of African slaves galvanized the growth of a mixed population of African descent. Second, notaries and masters were intentionally classifying enslaved people as mixed-race or of African descent.

Beyond the quantification of socio-racial classifications, manumission letters suggest the formation of vernacular notarial formulas emphasizing a black maternal genealogy for enslaved people. Consider the example of the mulato João de Deus. On April 14, 1777, the notary Carlos Câmara went to Teodosia Tereza Jesus's house in the Larga Street to record João's manumission. The two-page deed confirmed that Teodosia Jesus had received the deposit of 130$000 réis in exchange for granting João's freedom. Câmara wrote—reminiscent of Captain Araújo's defense and his witnesses—that Teodosia Jesus had João de Deus “in rightful title of slavery a mulato legitimate slave because he was the son of another slave named Florência, a black woman, and Florência was the daughter of another black woman legitimately enslaved called Tereza.”Footnote 85

These vernacular notarial formulas appear in records from the 1760s and 1770s and disappear in the 1780s. It was the moment after the publication of the 1755 abolition law and when several Indigenous workers were renegotiating the terms of their servitude, proving that the abolition of Indigenous enslavement did not weaken slavery as an institution.

Conclusion

Imperial reforms around the mid-eighteenth century transformed Maranhão's socioeconomic structure. The rise of a plantation economy, the thousands of enslaved Africans disembarking, and the new imperial policies toward Indigenous subjects impacted the lives of ordinary people in São Luís. Yet, these new forces did not remove Indigenous workers from the city, farms, and ranches. They offered new challenges and opportunities for the strategic use of the índio category.

The presence of Indigenous workers in the city and around it destabilized the colonial order. Their existence puzzled imperial surveyors. “It is difficult to accurately separate the three mentioned classes of people [White, Black, and Mulato],” wrote one of them in 1799, “without a rigorous investigation. There are mulatos almost white; mamelucos that descend from white and índios; cafuzos of mulato and preto; and mestiços of preto and índio; they easily pass into the nearest class. The wandering índios, those living outside the villages, were counted in the mulato class in their Parishes.”Footnote 86 The stories narrated in this article demonstrate that Indigenous workers were not as amorphous as the surveyors depicted them.

Histories of Indigenous enslavement described the process of captive commodification and the progressive transformation of Indigenous Americans into a servile population within colonial settlements. Because Indigenous enslavement was legally unstable, slaveholders concealed their workers’ Indigeneity to transform them into slaves.Footnote 87 The stories told here show the incompleteness of this narrative. Indigenous workers were resilient members of São Luís's community where they worked, socialized, formed friendship and romantic bonds, and attended the church. They restructured their lives and became índios within the colonial world.

For those Indigenous workers, many former slaves, representing themselves as índios involved mainly being reputed to be such. Three aspects comprised the índio reputation: genealogy, appearance, and labor. Over generations, the community formed knowledge about one person's lineage. A phenotypical assessment was as important as one's ancestors. Indigenous workers fought for their recognition as mobile wage laborers who had the right to serve whomever paid them better.

These transformations coincided with the growth of the transatlantic slave trade. The possibility of mass abolition and disruption of the order haunted slaveholders and colonial officials. During this period, vernacular practices—including notarial formulas—stressed the maternal black origins of the enslaved population. Vernacular practices hardened the racial lines of slavery, showed the limits of the strategic use of the índio, and preserved the reproduction of slavery, the bedrock of the Portuguese empire.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the help of Gautham Rao. The three anonymous readers at Law and History Review made this article immensely better. The author thanks Lauren Benton, Pedro Cardim, Celso Castilho, Rafael Chambouleyron, Roquinaldo Ferreira, Felipe Garcia, Carolina González, Jane Landers, Jorge Delgadillo Núñez, Ronald Raminelli, Heather Roller, and Victor Tiribás for reading and commenting on different versions of this article. Research for this article was funded by a James R. Scobie Award from the Conference on Latin American History (CLAH); the Luso-American Development Foundation (FLAD); the Center for Latin American, Caribbean, and Latinx Studies at Vanderbilt University; and the Social Science Research Council (SSRC).