Anxiety during pregnancy is estimated to affect between 15 and 23% of women and is associated with increased risk for a range of negative maternal and child outcomes.Reference Dennis, Falah-Hassani and Shiri1–Reference Dunkel-Schetter, Lobel, Revenson, Baum and Singer3 This has led to growing attention in researchReference Stein, Pearson, Goodman, Rapa, Rahman and McCallum4, Reference Rubertsson, Hellström, Cross and Sydsjö5 and clinical guidelines6 over recent years. Antenatal anxiety has been consistently found to be a strong predictor of postnatal anxiety and depression.Reference Milgrom, Gemmil, Bilszta, Hayes, Barnett and Brooks7–Reference Austin, Tully and Parker11 It has also been linked to adverse birth and child development outcomes, including low birth weight,Reference Field, Diego, Hernandez-Reif, Figuereido, Deeds and Ascencio12, Reference Diego, Jones, Field, Hernandez-Reif, Schanberg and Kuhn13 premature birthReference Dunkel-Schetter, Lobel, Revenson, Baum and Singer3, Reference Berle, Mykletun, Daltveit, Rasmussen, Holsten and Dahl14, Reference Ding, Wu, Xu, Zhu, Jia and Zhang15 and detrimental effects on neurodevelopmental, cognitive and behavioural child outcomes.Reference Stein, Pearson, Goodman, Rapa, Rahman and McCallum4, Reference Talge, Neal and Glover16, Reference Van Der Bergh, Mulder, Mennes and Glover17 Adverse child developmental outcomes found to be associated with antenatal anxiety include, for example, increased risk of language delay,Reference Talge, Neal and Glover16 attention-deficit hyperactivity disorderReference Talge, Neal and Glover16 and poorer emotional regulation.Reference Van Der Bergh, Mulder, Mennes and Glover17

Assessing anxiety in pregnancy

The importance of promoting the detection of women experiencing antenatal anxiety has been reflected in recent clinical guidelines. In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on perinatal mental health6 has for the first time recommended considering use of two screening questions (Generalised Anxiety Disorder scale, GAD-2)Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe18 for the case-identification of anxiety in pregnant and postnatal women, and the most recent Scottish guidelines have also called for further research in this area.19 However, the evidence for recommending the GAD-2 is primarily based on its good screening accuracy in the general population,20 with a very limited evidence base in perinatal populations. Although clinical diagnostic interviews are the optimal method of assessment for anxiety disorders, self-report rating scales such as the GAD-2 are often preferred in busy clinical practice and research because of their brevity.Reference Austin21

A recent systematic review found that self-reported anxiety symptoms during pregnancy had a pooled prevalence of 22.9% across trimesters.Reference Dennis, Falah-Hassani and Shiri1 For anxiety disorders based on DSM or ICD diagnostic criteria22, 23 the overall prevalence was 15.2%. Similar prevalence rates were reported in a number of studies showing that problematic anxiety symptoms affect approximately 15% of women, both in early pregnancyReference Rubertsson, Hellström, Cross and Sydsjö5 and in later stages.Reference Heron, O'Connor, Evans, Golding and Glover2, Reference Goodman, Chenausky and Freeman24 High levels of self-reported symptoms, as opposed to anxiety disorders, are of relevance as they have also been shown to be associated with negative maternal and child outcomes.Reference Grant, McMahon and Austin8, Reference Ding, Wu, Xu, Zhu, Jia and Zhang15 In research settings, antenatal anxiety has been measured with a heterogeneity of self-report scales, often in the absence of evidence of their psychometric accuracy in pregnant populations.Reference Evans, Spiby and Morrell25

Screening for antenatal anxiety using scales developed for the general population is problematic for various reasons, partly as a result of the unique nature of pregnancy. One of the main concerns relates to the emphasis of many self-report measures of general anxiety on somatic symptoms and their potential confounding role when questions around physical symptoms are used to screen for anxiety during pregnancy.Reference Swallow, Lindow, Masson and Hay26, Reference Marchesi, Ampollini, Paraggio, Giaracuni, Ossola and DePanfilis27 For instance, questions regarding sleep disturbances or palpitations, which are relatively common during pregnancy, may potentially lead to inflated scores. The assessment of antenatal anxiety is further complicated by the fact that anxiety symptoms that women can experience in pregnancy are not limited to the range of anxiety disorders determined by formal diagnostic criteria.22, 23

Pregnancy-specific anxiety

The occurrence of pregnancy-specific anxiety has been proposed as a distinct syndromeReference Huizink, Mulder, Robles De Medina, Visser and Buitelaar28 and a number of studies have investigated this unique anxiety type.Reference Phillips, Sharpe, Matthey and Charles29–Reference Huizink, Delforterie, Scheinin, Tolvanen, Karlsson and Karlsson31 This emerging construct refers to a particular anxiety response related to a current pregnancy, which can include fears and worries around labour and delivery, the health of the baby and expected changes in a woman's role.Reference Dunkel Schetter and Tanner32 There is now good evidence of the clinical distinctiveness of pregnancy-specific anxiety,Reference Westerneng, de Cock, Spelten, Honig and Hutton33, Reference Blackmore, Gustafsson, Gilchrist, Wyman and O'Connor34 and some studies indicate that pregnancy-specific anxiety may be a stronger predictor of negative child outcomes than general antenatal anxiety.Reference Blackmore, Gustafsson, Gilchrist, Wyman and O'Connor34 However, women who may be significantly anxious because of pregnancy-related concerns might not meet the diagnostic criteria for a DSM/ICD anxiety disorder and consequently go unrecognised.

Aims

Recent reviews on the psychometric properties of scales to measure perinatal anxiety have highlighted this gap and the lack of anxiety scales with sound psychometric properties for use with pregnant women.Reference Evans, Spiby and Morrell25, Reference Meades and Ayers35, Reference Brunton, Dryer, Saliba and Kohlhoff36 However, none of these reviews have examined the content of measures with published psychometric data in pregnant populations. Consequently, it remains crucial to establish which symptoms can be considered reliable and valid indicators of maternal antenatal anxiety.

The aim of the present paper was to systematically examine and synthesise both the psychometric properties and content of self-report scales used to assess anxiety in pregnancy in order to identify a core set of anxiety symptoms and anxiety domains with established psychometric properties in pregnant populations. This was achieved by conducting a systematic review of studies reporting at least one psychometric property (i.e. one aspect of reliability or validity) of a self-report measure used to assess antenatal anxiety and by appraising and summarising the best available evidence in the form of a narrative synthesis.

Method

The review was conducted based on guidance for undertaking reviews of clinical tests from the Centre of Reviews and Dissemination37 and COSMIN (COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurement INstruments) recommendations for systematic reviews of measurement properties,Reference Terwee38 and is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman39 Ethical approval was not required as the study only involved secondary analysis of anonymised data.

Search strategy and selection criteria

Computerised searches were performed to query the following electronic bibliographic databases: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). The initial objective of the review was to locate primary research articles reporting psychometric properties of self-report rating scales used to assess anxiety symptoms in a pregnant population.

The databases were searched from 1991 up to and including February 2017 and searches were restricted to articles published in peer-reviewed journals and available in English. A combination of four main themes was used in the search. Specifically, the major concepts searched were ‘anxiety’, ‘pregnancy’, ‘measurement’ and ‘psychometrics’ and search terms included both free text and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms. Major concepts and related synonyms for the four main themes were searched in the title and abstract fields, with several key terms also searched as a major concept within each database (see supplementary Appendix 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2018.75).

Reference lists and citation records of papers included in the review were also inspected for potential inclusion of additional studies. Reports, commentaries, conference proceedings and other grey literature were not searched. Methodological search filters were not applied as there is evidence that, because of the variety of designs used in studies of diagnostic or screening test accuracy, applying methodological filters is likely to result in the omission of a significant number of relevant studies.Reference Leeflang, Scholten, Rutjes, Reitsma and Bossuyt40, Reference Whiting, Westwood, Beynon, Burke, Sterne and Glanville41 A predefined list of inclusion and exclusion criteria was applied in relation to type of study, population, construct of interest and type of measurement. A complete list of inclusion and exclusion criteria is provided in the Appendix.

Study selection and data extraction

All articles resulting from the electronic bibliographic database searches were imported into RefWorks and duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts of articles resulting from the initial search were reviewed to identify potentially relevant studies. When there was an indication that an article may have met the inclusion criteria for the review, the full-text publication was obtained and reviewed. The lead reviewer (A.S.) screened titles and abstracts of all retrieved articles to determine their appropriateness for inclusion in the review. A second reviewer (H.C.) independently screened a sample (10%) of all retrieved articles to establish an index of interrater agreement determined as per cent agreement,Reference McHugh42 which was 98% for titles and abstracts screened by both reviewers. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved by applying the relevant study eligibility criteria to reach consensus.

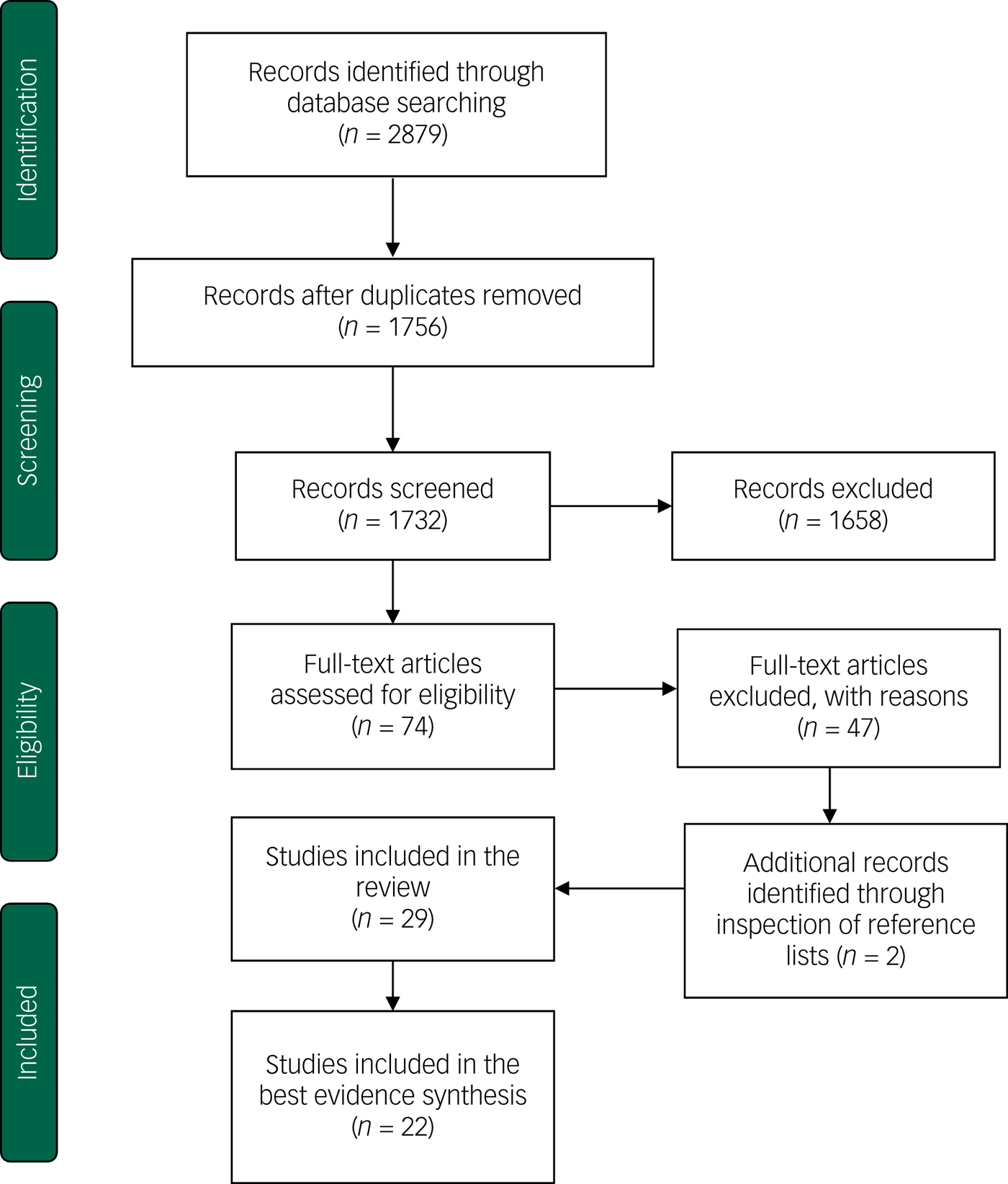

The PRISMA flow diagramReference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman39 was used to document the different stages of the study selection process (Fig. 1). In relation to data extraction, the full-text article of all studies included in the review was inspected and the full version of the rating scale used was obtained in order to extract information relevant to the review. Data extraction forms and summary tables were developed and piloted on a small number of studies (n = 6) identified as eligible for inclusion at an early stage of the review.

Fig. 1 PRISMA flow diagram of the selection process (based on Moher et al).Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman39

For each included study the following information was extracted: (a) author/s, (b) year of publication, (c) country, (d) name of index test, (e) sample size, (f) timing of assessment (expressed as trimester or mean gestational week), (g) construct of interest. For each of the rating scales, we extracted: (a) number of items, (b) type and number of response options (for example Likert scale, dichotomous), (c) time frame assessed (for example past week, past month), (d) score range, (e) total possible score, (f) cut-off score (if available). In order to determine which psychometric properties were evaluated in each study, the COSMIN taxonomy and definitions of measurement properties were used.Reference Mokkink, Terwee, Patrick, Alonso, Stratford and Knol43 The following psychometric properties were extracted: internal consistency reliability, construct validity, convergent and discriminant validity, structural (i.e. factorial) validity and criterion validity. Definitions of all psychometric properties examined in this review and their corresponding indexes are presented in supplementary Appendix 2.

Quality assessment

An assessment of the methodological quality of each study included in the review was conducted using the COSMIN checklist, specifically developed to evaluate the study quality and risk of bias in systematic reviews of studies on the measurement properties of health measurement instruments.Reference Mokkink, Terwee, Knol, Stratford, Alonso and Patrick44 In this review, five of the nine possible boxes in the checklist were employed as they were considered to be relevant to evaluate the methodological quality of studies assessing the construct of anxiety in pregnancy.

Specifically, these were box A (internal reliability), D (content validity), E (structural validity), F (hypotheses testing) and H (criterion validity). Each measurement property is scored on a four-point rating scale as ‘poor’, ‘fair’, ‘good’ or ‘excellent’. An overall score for the methodological quality of a study is determined by using a ‘worse score counts’ system.Reference Terwee, Mokkink, Knol, Ostelo, Bouter and de Vet45 The lead reviewer (A.S.) performed the quality assessment for all studies included in the review, with the second reviewer (H.C.) assessing a random sample of studies (n = 5) to confirm the accuracy of the scoring system. It was decided that only studies that achieved an overall rating of good or excellent were considered in the best-evidence synthesis in order to guarantee the quality of the conclusions reached by the review.

Best-evidence synthesis

The main aim of this review was to examine the psychometric properties and content of anxiety measures used in pregnancy, both at the scale and at the item level, in order to identify specific items (i.e. questions) or anxiety domains with established psychometric properties in this population. A synthesis of the best available evidence is presented for each scale in a narrative form, as the considerable differences across studies in relation to measure used, sample size, time of administration and type of reliability or validity reported precluded a meta-analysis. At the scale level, the psychometric properties discussed above were examined and synthesised. The number of studies, their methodological quality and the consistency of findings were taken into account.

Specifically, the following criteria were used to classify the strength of evidence from one or more studies, based on COSMIN recommendations for quality criteria:Reference Terwee, Bot, de Boer, van der Windt, Knol and Dekker46 (a) strong evidence: consistent findings in multiple studies of good or excellent methodological quality or in one study of excellent quality, (b) moderate evidence: consistent findings in multiple studies of good or excellent quality, except for one study with contrasting findings, (c) limited evidence: one study of good methodological quality, and (d) unclear or conflicting evidence: contrasting results in multiple studies of good quality. Only items and anxiety domains with moderate or strong evidence of being accurate indicators of anxiety symptoms in pregnancy were considered psychometrically sound in assessing antenatal anxiety.

At the item level, the analysis was primarily based on factor analysis, and specifically on the examination and comparison of coefficients of item loadings on specific anxiety factors for each scale. In psychometrics, the examination of item loadings is recommended in order to determine which items within a scale possess the strongest psychometric properties in terms of their discriminative power,Reference Streiner, Norman and Cairney47 and can be therefore considered to detect an important aspect of the construct assessed.Reference DeVellis48 Factor analysis is used to reduce variables (i.e. single items) that share common variance into set of clusters (i.e. factors).Reference Bartholomew, Knotts and Moustaki49

In this review, the criteria proposed by Tabachnick & FidellReference Tabachnick and Fidell50 and listed as follows were adopted to evaluate the strength of item loading coefficients: (a) 0–0.44, poor; (b) 0.45–0.54, fair; (c) 0.55–0.62, good; (d) 0.63–0.70, very good; (e) >0.70, excellent. Only items that showed very good or excellent loadings (i.e. 0.63 or above), and for which the strength of evidence from one or multiple studies was moderate or strong according to the criteria discussed above, were considered to be psychometrically sound in measuring anxiety symptoms in pregnancy. When items forming a factor were found to be particularly homogeneous in relation to their content, the entire dimension or domain that the factor represented rather than individual items was selected as a domain identified as psychometrically sound. Secondary indexes that were examined at the item level when factor analysis was not conducted were the correlations between individual items and the remainder of items within a scale (corrected item-total correlations) and item discrimination parameters for analyses based on item-response theory models.

Results

The initial search yielded 2879 citations, which were reduced to 1756 following de-duplication. The titles and abstracts of remaining articles were screened for potentially eligible studies, resulting in 74 publications for which the full-text article was retrieved. At this stage 47 studies were excluded and 2 publications were added from hand searches of reference lists of included studies. This resulted in a final sample of 29 studies included in the review.Reference Grant, McMahon and Austin8, Reference Austin, Tully and Parker11, Reference Huizink, Mulder, Robles De Medina, Visser and Buitelaar28, Reference Huizink, Delforterie, Scheinin, Tolvanen, Karlsson and Karlsson31, Reference Westerneng, de Cock, Spelten, Honig and Hutton33, Reference Bayrampour, McDonald, Fung and Tough51–Reference Zhong, Gelaye, Zaslavsky, Fann, Rondon and Sanchez74 The main reasons for excluding studies after retrieving the full text were: (a) no psychometric data available, (b) construct of interest different from inclusion criteria (for example antenatal stress, general mental health), (c) study participants recruited exclusively from high-risk samples. The study selection process is summarised in the PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1).

The 29 included studies used 9 different scales as index tests to measure antenatal anxiety. The most commonly reported psychometric properties were internal consistency reliability (n = 27; 93% of studies), convergent validity (n = 21; 72%) and structural validity (n = 16; 55%). The characteristics of included studies are presented in Table 1. Included studies showed a considerable degree of heterogeneity in relation to the construct assessed (i.e. general anxiety versus an anxiety disorder versus pregnancy-specific anxiety), gestational age of participants, sample size and type of psychometric properties reported.

Table 1 General characteristics of studies included in the review

BMWS, Brief Measure of Worry Severity; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; EPDS-A, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale – Anxiety subscale; CWS, Cambridge Worry Scale; W-DEQ, Wijma Delivery Expectancy/Experience Questionnaire; PRAQ-R and PRAQ-R2, Pregnancy-Related Anxiety Questionnaire- Revised; HADS-A; Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Anxiety subscale; PAS, Pregnancy Anxiety Scale; GAD-7, Generalised Anxiety Disorder – 7.

As discussed in the Method, a quality assessment of all included studies was performed and only studies achieving a rating of good or excellent in relation to their methodological quality and risk of bias were included in the best-evidence synthesis. Seven studies were given a rating of poorReference Haines, Pallant, Fenwick, Gamble, Creedy and Toohill59, Reference Öhman, Grunewald and Waldenström68, Reference Tendais, Costa, Conde and Figueiredo72 or fairReference Garthus-Niegel, Størksen, Torgersen, Von Soest and Eberhard-Gran56, Reference Jomeen and Martin62, Reference Levin65, Reference Simpson, Glazer, Michalski, Steiner and Frey70 for their methodological quality and were thus not considered in the synthesis. The quality assessment of all 29 studies included in the review is presented in the supplementary Table 1. Further details about the criteria used to rate the methodological quality of all studies included are available from the corresponding author on request.

Best-evidence synthesis

Following an assessment of the methodological quality of all studies, 22 were included in the best-evidence synthesis phase of the review.Reference Grant, McMahon and Austin8, Reference Austin, Tully and Parker11, Reference Huizink, Mulder, Robles De Medina, Visser and Buitelaar28, Reference Huizink, Delforterie, Scheinin, Tolvanen, Karlsson and Karlsson31, Reference Westerneng, de Cock, Spelten, Honig and Hutton33, Reference Bayrampour, McDonald, Fung and Tough51–Reference Fenaroli and Saita55, Reference Gourounti, Lykeridou, Taskou, Kafetsios and Sandall57, Reference Green, Kafetsios, Statham and Snowdon58, Reference Johnson and Slade60, Reference Jomeen and Martin61, Reference Jomeen and Martin63, Reference Karimova and Martin64, Reference Marteau and Bekker66, Reference Matthey, Valenti, Souter and Ross-Hamid67, Reference Petersen, Paulitsch, Guethlin, Gensichen and Jahn69, Reference Swalm, Brooks, Doherty, Nathan and Jacques71, Reference Wijma, Wijma and Zar73, Reference Zhong, Gelaye, Zaslavsky, Fann, Rondon and Sanchez74 This section discusses the findings from these studies through an examination of the psychometric properties of each scale and a critical analysis of the content of their items and anxiety domains found to be psychometrically sound for the assessment of antenatal anxiety. This analysis was carried out accordingly to the criteria discussed in detail in the Method. For clarity of exposition, a synthesis is presented here separately for each scale, whereas the Discussion summarises the general findings of the review.

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) – Anxiety subscale

The EPDSReference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky75 is a ten-item self-report questionnaire originally developed to screen for postpartum depression, which asks respondents about symptoms of depression experienced in the previous week. Because of the lack of items specific to the postpartum period, the EPDS has also been validated for use with pregnant women.Reference Murray and Cox76, Reference Green, Murray, Cox and Holden77 Although the EPDS was developed as a unidimensional measure of depression, it was included in this review because of growing evidence that it contains a separate subscale measuring anxiety rather than depressive symptoms, in both antenatal and postnatal populations.Reference Pop, Komproe and van Son78–Reference Matthey, Fisher and Rowe80

Six studies included in this review examined the psychometric properties of the EPDS anxiety subscale in pregnant women. All studies except oneReference Simpson, Glazer, Michalski, Steiner and Frey70 achieved an overall methodological quality rating of goodReference Brouwers, van Baar and Pop52, Reference Matthey, Valenti, Souter and Ross-Hamid67, Reference Swalm, Brooks, Doherty, Nathan and Jacques71 or excellentReference Coates, Ayers and Visser54, Reference Jomeen and Martin63 and were thus included in the best-evidence synthesis. Four of the five studies examined the factor structure of the EPDS to investigate whether the existence of an anxiety subscale could be confirmed.

Brouwers and colleaguesReference Brouwers, van Baar and Pop52 performed exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of EPDS scores in women in their second trimester of pregnancy. The EFA revealed three components within the EPDS, namely two separate depressive (items 1, 2, 8) and anxiety (items 3, 4, 5) symptoms subscales and a third component consisting only of item 10 (‘The thought of harming myself has occurred to me’). However, this third factor was not included in the final factor solution as the authors argued that a single-item loading could not plausibly identify a distinct latent factor.Reference Brouwers, van Baar and Pop52 A two-factor solution, comprising separate depression and anxiety subscales, was therefore proposed. The three items of the anxiety subscale (item 3 ‘I have blamed myself unnecessarily when things went wrong’, item 4 ‘I have been anxious or worried for no good reason’, item 5 ‘I have felt scared or panicky for no very good reason’) were the only ones, among the ten EPDS items, with item loadings on a single factor above the predefined cut-off of 0.63, ranging from 0.68 (item 3) to 0.73 (item 4). An examination of their content appears to indicate that these questions, all loading highly on a single factor, tap important affective and cognitive components of anxiety (for example feeling panicky or worried).

Similar findings were reported by Jomeen & MartinReference Jomeen and Martin63 in women in their first trimester of pregnancy. EFA resulted in a three-factor solution that included depression and anxiety dimensions, and the same third factor identified by Brouwers and colleagues.Reference Brouwers, van Baar and Pop52 The items loading significantly (>0.63, range 0.73–0.85) onto the anxiety subscale were entirely consistent (items 3, 4, 5) with those identified in the previous study.Reference Brouwers, van Baar and Pop52 The authors then conducted confirmatory factory analysis (CFA), a more refined data reduction technique than EFA,Reference Child81 and tested various predefined factor models including the original unidimensional depression model,Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky75 as well as both a two- and a three-factor model identified by Brouwers and colleagues.Reference Brouwers, van Baar and Pop52 Results from the CFA revealed once again a clear superiority of the two-factor solution, thus confirming the previous finding that the EPDS both in early and in mid-pregnancy consistently measures two distinct dimensions of depression and anxiety.

A further study included in this reviewReference Matthey, Valenti, Souter and Ross-Hamid67 used the three-item EPDS anxiety subscale (EDS-3A) identified in previous studies to examine its criterion and convergent validity in pregnancy when compared with other anxiety measures. The EDS-3A performed better than both the anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-AReference Zigmond and Snaith82) and the Pregnancy Related Anxiety Questionnaire-Revised (PRAQ-RReference Huizink, Mulder, Robles De Medina, Visser and Buitelaar28) in detecting women with an anxiety disorder as determined by DSM diagnostic criteria. Furthermore, the EDS-3A showed a moderately high correlation with the HADS-A (r = 0.68) and a low to moderate correlation with the PRAQ-R (r = 0.23), which may be interpreted as an indication that the three measures tap into different aspects of antenatal anxiety.

Although a potential limitation of the three studies reported above is their relatively small number of participants (n < 200), the existence of an anxiety subscale within the EPDS was further confirmed in two subsequent studies with much larger numbers of participants (n > 4000). Swalm and colleaguesReference Swalm, Brooks, Doherty, Nathan and Jacques71 examined the EPDS factor structure in Australian women across the three trimesters of pregnancy. A two-factor solution consisting of anxiety and depression components was found once more to be optimal, accounting for 55% of the score variance (anxiety subscale 29.4%; depression subscale 25.4% of the total variance). Moreover, an analysis of individual item loadings confirmed that items 3, 4 and 5 were the only ones with loadings higher than 0.63 on the anxiety subscale (range 0.75–0.78).

A recent UK population-based studyReference Coates, Ayers and Visser54 conducted both EFA and CFA on a large number of participants at two time points (18 and 32 weeks’ gestation). Although both EFA and CFA indicated a three-factor model as the best factor solution, this was primarily because of the ‘depression’ factor that was split into an anhedonia (items 1 and 2) and a depression (items 7–10) factor. Importantly, this was the only study in which item 3 ‘I have blamed myself unnecessarily when things went wrong’ (0.56) did not reach the predefined item loading coefficient of 0.63.

In summary, according to the criteria previously discussed to evaluate the strength of evidence in relation to the psychometric properties of reviewed scales, item 3 of the EPDS showed moderate evidence of its psychometric value, and items 4 and 5 demonstrated strong evidence of being psychometrically sound in assessing antenatal anxiety, as their item loadings on the anxiety subscale consistently exceeded the 0.63 cut-off in all reviewed studies.

HADS – Anxiety subscale

The HADSReference Zigmond and Snaith82 is a widely popular screening toolReference Cosco, Doyle, Ward and McGee83 originally developed to assess anxiety and depression in non-psychiatric patients. This 14-item measure consists of two subscales (anxiety: HADS-A; depression: HADS-D), both comprising seven items and enquiring about feelings over the past week with four response options.Reference Zigmond and Snaith82 It is particularly important to establish the psychometric properties of the HADS when used in the antenatal period, as a considerable number of studies have used this screening tool to assess anxiety and depression levels in pregnant women, including in recent years.Reference Rubertsson, Hellström, Cross and Sydsjö5, Reference Owen, Wood, Tomenson, Creed and Neilson84

Three studies included in this review examined psychometric aspects of the HADS in a pregnant population.Reference Jomeen and Martin61, Reference Karimova and Martin64, Reference Matthey, Valenti, Souter and Ross-Hamid67 They all achieved a rating of good in relation to their methodological quality. Karimova & MartinReference Karimova and Martin64 investigated the factor structure of the HADS in the third trimester of pregnancy by conducting EFA of HADS scores in nulliparous women, and a post hoc factor analysis revealed a two-factor solution. Specifically, six of the seven HADS-D items loaded higher on one factor and an equal number of HADS-A items loaded higher on a second factor. However, there was significant overlapping of item loadings on the two subscales, with only four HADS-A items (item 3 ‘I get a sort of frightened feeling as if something awful is going to happen’; item 5 ‘Worrying thoughts go through my mind’; item 9 ‘I get a sort of frightened feeling like “butterflies” in the stomach’ and item 13 ‘I get sudden feelings of panic’) loading above 0.63 on the anxiety factor. The authors therefore concluded that the seven-item HADS-A and HADS-D subscales do not reliably distinguish between anxiety and depressive symptoms in pregnancy.

A further study was conducted by Jomeen & MartinReference Jomeen and Martin61 on women in early pregnancy. Both EFA and CFA revealed a three-factor solution that confirmed that the HADS in pregnancy is not a bi-dimensional measure of anxiety and depression. However, a comparison of individual item loadings of the HADS anxiety subscale in the two studies was carried out in this review to examine psychometric information for each individual item within the HADS anxiety subscale. This is presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Item loading coefficients of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Anxiety subscale (HADS-A) subscale in Karimova & MartinReference Karimova and Martin64 and Jomeen & MartinReference Jomeen and Martin61

a. Item loadings of 0.63 or above.

The observation that three items of the HADS-A (items 3, 5, 13) are the only ones to reach an item loading above 0.63 on the anxiety factor in both studies is of particular importance. Although the two studies reached the conclusion that the seven-item HADS-A as a whole is not a psychometrically sound measure of anxiety in pregnancy, the three HADS-A items identified here showed a consistent pattern across the two studies, with significantly similar loadings on the anxiety factor. These items would therefore appear to have good psychometric value in assessing specific anxiety symptoms in pregnancy.

A subsequent studyReference Matthey, Valenti, Souter and Ross-Hamid67 compared the screening performance of the HADS-A with diagnosis of an anxiety disorder according to DSM criteria. The authors found that high anxiety scores on the HADS-A, defined as the top 15% of scores, had poor concordance (34%) with formal diagnosis of an anxiety disorder. The poor concordance with DSM diagnoses seems to confirm the previous findings indicating that the seven-item HADS anxiety subscale as a whole is not a reliable screening tool to assess anxiety in pregnancy. However, based on the evidence provided by the two studies discussed above on the factor structure of the HADS, we conclude that the three identified items represent a shortened version of the HADS-A which, unlike the entire HADS-A, has good evidence of its psychometric properties to measure antenatal anxiety.

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)

The STAIReference Spielberger, Gorsuch and Lushene85 comprises two subscales, each composed of 20 items. It is based on a model of anxiety that distinguishes between state and trait anxiety.Reference Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagge and Jacobs86 State anxiety refers to the situation-specific, transient component of anxiety. Conversely, trait anxiety reflects a relatively stable personality trait, a dispositional anxiety proneness.Reference Green, Kafetsios, Statham and Snowdon58 Response options range from one (not at all) to four (very much so) for both the state and trait form, and each scale includes ten anxiety-present (for example ‘I am worried’) and ten anxiety-absent (for example ‘I feel secure’) items. The state form asks participants about feelings at the present time, whereas the trait form enquires about how a respondent generally feels. The STAI has been widely validated in the general populationReference Austin, Tully and Parker11 and is one of the most common measures used in research to assess anxiety in perinatal women.Reference Meades and Ayers35

This review located four studies reporting psychometric properties of the STAI in pregnant populations, one of whichReference Tendais, Costa, Conde and Figueiredo72 was scored poor in relation to its methodological quality. Both the state and trait form of the STAI were used in an Australian study by Grant and colleaguesReference Grant, McMahon and Austin8 on women in the third trimester of pregnancy. Internal consistency was found to be high for the full version of the scale, with a Cronbach's alpha (α) of 0.95. A structured diagnostic interview was also used (Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview)Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Harnett-Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs and Weiller87 to identify women meeting DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for an anxiety disorder. The authors found a cut-off score of 40 to yield the highest accuracy in identifying women with a diagnosed anxiety disorder, with a sensitivity of 80.9% and a specificity of 79.7%.Reference Grant, McMahon and Austin8 However, they also acknowledged the limited generalisability of the findings because of the relatively small number of participants. The study did not provide any psychometric data at the item level and it was thus not possible to reach conclusions on the psychometric qualities of individual items measuring specific symptoms.

A further studyReference Marteau and Bekker66 tested various shortened versions of the STAI-S form to determine the smallest subset of items that preserved high correlations (r > 0.90) with the original, 20-item STAI-S. They found that a six-item version produced scores comparable with the full version (r > 0.94) while retaining a good level of internal consistency (α = 0.82). The six items selected were the ones with the highest correlations with the remaining 19 items of the STAI-S (i.e. corrected item-total correlations). Specifically, the authors identified three anxiety-present and three anxiety-absent items, corresponding to the following emotional states: calm, tense, upset, relaxed, content and worried. This is a significant finding, as it identifies a number of symptoms (i.e. feeling tense, upset or worried) that correlate highly with the 20-item STAI-S total score, providing an initial indication that these anxiety-present symptoms may be considered relatively accurate indicators of problematic anxiety in pregnancy.

This was confirmed in a further study by Bayrampour and colleaguesReference Bayrampour, McDonald, Fung and Tough51 that examined the psychometric properties of three six-item shortened versions of the STAI-S when compared with the full state form. The three short versions are the ones discussed aboveReference Marteau and Bekker66 and two other versions developed in non-perinatal populations. The six-item version by Marteau & BekkerReference Marteau and Bekker66 had the highest correlation with the sum score of the full form (r = 0.94). Furthermore, confirmatory factory analysis was conducted and the version by Marteau & BekkerReference Marteau and Bekker66 was found once more to consistently have the best values for all fit indexes considered, with the three anxiety-present items (i.e. feeling tense/upset/worried) all found to have coefficient item loadings above 0.63, a further indication of their psychometric soundness.

In sum, the three items from the STAI-S short form discussed above were identified in two studies of good methodological qualityReference Bayrampour, McDonald, Fung and Tough51, Reference Marteau and Bekker66 as potentially reliable indicators of anxiety symptoms during pregnancy.

GAD-7

The GAD-7Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe18 was developed in 2006 as a brief screening measure for generalised anxiety disorder. Its original psychometric validation study, in a large number of primary care patients indicated very good screening accuracy in identifying people with a diagnosis of generalised anxiety disorder.Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe18 The scale consists of seven items asking respondents about some of the core generalised anxiety disorder symptoms (for example excessive or persistent worry, trouble relaxing) experienced in the previous 2 weeks. As previously discussed, the first two questions of the GAD-7 (GAD-2) have been recently recommended by NICE as a brief screening measure for anxiety in perinatal women.6

Only two studies examining the measurement properties of the GAD-7 in a pregnant population were identified by this review,Reference Simpson, Glazer, Michalski, Steiner and Frey70, Reference Zhong, Gelaye, Zaslavsky, Fann, Rondon and Sanchez74 and only oneReference Zhong, Gelaye, Zaslavsky, Fann, Rondon and Sanchez74 achieved a satisfactory rating for its methodological quality. Importantly, this was one of the few included studies that performed assessment of a scale against a gold-standard clinical interview, the Composite International Diagnostic Interview,Reference Kessler and Üstün88 to determine the criterion validity of the scale. In this antenatal sample at a cut-off score of seven or above, notably different from the cut-off of ten identified in the general population, the measure yielded moderately good sensitivity (73%) and specificity (67%).Reference Zhong, Gelaye, Zaslavsky, Fann, Rondon and Sanchez74 Internal consistency was close to excellent (α = 0.89).

Both EFA and CFA were conducted, and confirmed the unidimensional structure (i.e. a single factor) of the GAD-7 previously found in the general population.Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe18 The results of the factor analysis indicated that the seven items loaded on a single factor with item loadings all exceeding 0.63. In order to identify which items provided the most accurate screening performance we thus examined the item discrimination parameters, which are based on item-response theory and indicate how well individual items differentiate between different levels of the target condition among respondents.Reference Li and Baser89 Two items showed considerably higher discrimination parameter estimates than the remaining ones. These were item 3 ‘Worrying too much about different things’ (2.05) and item 2 ‘Not being able to stop or control worrying’ (2.04), which clearly tap into the experience of pervasive or persistent worry typical of generalised anxiety disorder. All other items exhibited substantially lower discrimination parameter estimates. Considering that this study was of excellent methodological quality, the two identified items have consequently strong evidence of their psychometric value in the antenatal period.

Brief Measure of Worry Severity (BMWS)

A single studyReference Austin, Tully and Parker11 was located reporting psychometric data of the BMWSReference Gladstone, Parker, Mitchell, Malhi, Wilhelm and Austin90 in pregnant women. Self-report scales assessing the construct of ‘worry’ were included in this review (Appendix 1) as worry is a core clinical feature of generalised anxiety disorder.22, Reference Cuijpers, Sijbrandij, Koole, Huibers, Berking and Andersson91 A number of studies indicate that generalised anxiety disorder is the most common anxiety disorder in pregnancyReference Dennis, Falah-Hassani and Shiri1, Reference Tendais, Costa, Conde and Figueiredo72 and for this reason worry can be hypothesised to be an important dimension of the construct of antenatal anxiety. The BMWS was developed as a unidimensional measure of the functional impact and severity of worry.Reference Gladstone, Parker, Mitchell, Malhi, Wilhelm and Austin90 It includes eight items assessing different aspects of worry. Respondents are asked to rate their general or usual experience of worrying, with four verbally anchored response options (not true at all – definitely true).Reference Gladstone, Parker, Mitchell, Malhi, Wilhelm and Austin90

Austin et al aimed to determine whether the construct of worry as measured by the BMWS, defined as ‘dysfunctional trait cognitive anxiety’, was a significant predictor of postnatal depression.Reference Austin, Tully and Parker11 Internal consistency was very good (α = 0.89) and the BMWS also showed good convergent validity with the STAI trait (r = 0.71). Although psychometric properties of the scale at the item level were not reported, there was evidence that the construct of worry as measured by the BMWS is a reliable indicator of antenatal anxiety. First, the BMWS was found to have good construct validity in these pregnant participants, as it showed significant correlations with a number of other variables linked to a current episode of anxiety and depression.Reference Austin, Tully and Parker11 Moreover, it was a better predictor of postnatal depression than the STAI-S after controlling for possible confounding factors. As the literature indicates that antenatal anxiety is a predictor of postnatal depression,Reference Milgrom, Gemmil, Bilszta, Hayes, Barnett and Brooks7, Reference Grant, McMahon and Austin8, Reference Sutter-Dallay, Giaconne-Marcesche, Glatigry-Dallay and Verdoux10 it appears than the BMWS taps into a core component of antenatal anxiety considering its good predictive validity.

Consequently, the construct of worry has strong evidence of being psychometrically robust according to the criteria used in this review (i.e. consistent findings in multiple studies of good or excellent methodological quality) as it was also identified as psychometrically sound in other studies previously discussed in this synthesis.

Cambridge Worry Scale (CWS)

The CWS is a 16-item measure assessing the extent and content of women's worries during pregnancy.Reference Green, Kafetsios, Statham and Snowdon58 The 16 items in the CWS enquire both about worries specific to pregnancy, such as ‘The possibility of miscarriage’, ‘The possibility of something being wrong with the baby’ or ‘Giving birth’, and more general concerns including ‘Money problems’ and ‘Your relationship with your family and friends’. Items are scored on a six-point Likert-type scale with verbally described anchors ranging from zero (not a worry) to five (major worry) and referring to the present time.Reference Green, Kafetsios, Statham and Snowdon58

Six studies examining psychometric aspects of the CWS in a pregnant population were included in this review, four of which are considered here. The other two studies were rated as poorReference Öhman, Grunewald and Waldenström68 or fairReference Jomeen and Martin62 for their methodological quality.

Green and colleaguesReference Green, Kafetsios, Statham and Snowdon58 were the first to investigate the structural validity (i.e. the factor structure) of the CWS. A longitudinal design was used in a large number (n = 1207) of British women completing the CWS at gestational weeks 16, 22 and 35. The authors analysed scores at these three time points by means of principal component analysis (PCA), a form of exploratory factor analysis. The PCA revealed a four-factor structure, consisting of the following factors: (a) socio-medical aspects of having a baby, (b) socio-economic issues, (c) health of mother and baby, and (d) relationships with partner, family and friends. This four-factor solution was subsequently replicated in all the other studies examined in this synthesis.Reference Carmona Monge, Peñacoba-Puente, Marín Morales and Carretero Abellán53, Reference Gourounti, Lykeridou, Taskou, Kafetsios and Sandall57, Reference Petersen, Paulitsch, Guethlin, Gensichen and Jahn69 This can be considered robust evidence of factorial stability of the CWS in different populations and stages of pregnancy.

The convergent validity of the CWS was examined by comparing it with STAI state and trait scoresReference Gourounti, Lykeridou, Taskou, Kafetsios and Sandall57, Reference Green, Kafetsios, Statham and Snowdon58, Reference Petersen, Paulitsch, Guethlin, Gensichen and Jahn69 and with the anxiety subscale of the Symptom Checklist-90Reference Derogatis92 by Carmona Monge and colleagues.Reference Carmona Monge, Peñacoba-Puente, Marín Morales and Carretero Abellán53 Two of the four CWS subscales were found to have the highest correlations with state anxiety (STAI-S) scores across studies. These were the ‘socio-medical’ and the ‘health of mother and baby’ factors. For the purpose of this review, we specifically focused on these two factors, both because of their higher correlations with state anxiety and because the content of items in these subscales appears to reflect worries more closely related to pregnancy. Thus, an examination of individual item loadings for these two factors was carried out.

In relation to the ‘socio-medical’ subscale, one item (‘Giving birth’) was found to load above the predefined criterion of 0.63 in all studies, thus demonstrating strong evidence of its psychometric properties in assessing a major worry in pregnancy. Another three items showed moderate strength of evidence as they loaded above 0.63 on the ‘socio-medical’ subscale in all studies apart from one. Specifically, ‘Internal examinations’ had an item loading coefficient of 0.61 in Gourounti and colleagues,Reference Gourounti, Lykeridou, Taskou, Kafetsios and Sandall57 but item loadings above 0.63 in all the other studies; ‘Going to hospital’ (0.68–0.79), apart from Gourounti and colleaguesReference Gourounti, Lykeridou, Taskou, Kafetsios and Sandall57 (0.47); and ‘Coping with the new baby’ (0.65–0.68), except for the study by Petersen and colleagues,Reference Petersen, Paulitsch, Guethlin, Gensichen and Jahn69 in which its loading was 0.58.

An inspection of the second factor examined, ‘Health of mother and baby’, indicated two further items with loadings >0.63 in all the studies, namely ‘The possibility of miscarriage’, which ranged between 0.75Reference Green, Kafetsios, Statham and Snowdon58 and 0.85Reference Carmona Monge, Peñacoba-Puente, Marín Morales and Carretero Abellán53, and ‘The possibility of something being wrong with the baby’ (range 0.65–0.83Reference Carmona Monge, Peñacoba-Puente, Marín Morales and Carretero Abellán53, Reference Green, Kafetsios, Statham and Snowdon58). The other two items included in this subscale, ‘Own health’ and ‘Health of someone else close’, consistently loaded below the pre-defined cut-off.

In summary, three items of the CWS (‘Giving birth’, ‘The possibility of miscarriage’, ‘The possibility of something being wrong with the baby’) demonstrated strong evidence of their psychometric properties. Three further items (‘Internal examinations’, ‘Going to hospital’ ‘Coping with the new baby’) showed a moderate strength of evidence of their psychometric value in pregnancy.

Wijma Delivery Expectancy/Experience Questionnaire (W-DEQ – Version A)

The W-DEQReference Wijma, Wijma and Zar73 was developed in the late nineties to assess the construct of fear of childbirth. Within the research literature on pregnancy-specific anxiety, fear of childbirth or tokophobia has emerged as a central dimension of pregnancy-specific anxiety.Reference Rubertsson, Hellström, Cross and Sydsjö5, Reference Blackmore, Gustafsson, Gilchrist, Wyman and O'Connor34, Reference Heimstad, Dahloe, Laache, Skogvoll and Schei93 The W-DEQ Version AReference Wijma, Wijma and Zar73 includes 33 items enquiring about thoughts and feelings relating to the approaching childbirth, with six response options ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘extremely’.

Five studies included in the present review reported psychometric information on the W-DEQ in an antenatal population,Reference Fenaroli and Saita55, Reference Garthus-Niegel, Størksen, Torgersen, Von Soest and Eberhard-Gran56, Reference Haines, Pallant, Fenwick, Gamble, Creedy and Toohill59, Reference Johnson and Slade60, Reference Wijma, Wijma and Zar73 and three studies achieved a good or excellent methodological quality rating.Reference Fenaroli and Saita55, Reference Johnson and Slade60, Reference Wijma, Wijma and Zar73 In the original development study of the W-DEQ,Reference Wijma, Wijma and Zar73 internal consistency of the measure was excellent (α = 0.93). The authors also provided good evidence of the face and construct validity of the W-DEQ, with all items formulated based on the clinical experience of the first two authors and incorporating women's input in the wording of items. The W-DEQ showed higher correlations with other anxiety measures than with extraversion or depression measures. However, these correlations were only moderate (STAI-T: r = 0.54; S-R Inventory of anxiousness: r = 0.52), thus showing a degree of conceptual overlap but also a sufficient level of variance left to indicate that the W-DEQ measures other than anxiety as a dispositional trait.Reference Wijma, Wijma and Zar73

At the item level, item-total correlations were ranked and the authors examined the ten items with the highest ranking. Two domains of fear of childbirth, ‘Negative feelings towards childbirth’ and ‘Fear of labour and delivery’, were identified among the items more strongly correlated with the sum score, thus suggesting a stronger relation with the overall construct of fear of childbirth. As single items composing the W-DEQ are very specific to a given feeling or cognitive appraisal, we considered it appropriate to focus on domains of fear of childbirth rather than individual items.

Two other studiesReference Fenaroli and Saita55, Reference Johnson and Slade60 included in this synthesis conducted factor analysis of W-DEQ scores and found four distinct dimensions of the construct of fear of childbirth as measured by the scale. Johnson & SladeReference Johnson and Slade60 named the four identified domains Fear, Lack of positive anticipation, Isolation and Riskiness. The latter two refer to feelings of isolation related to childbirth and to the extent to which women anticipate risks for the child during delivery. Fenaroli & SaitaReference Fenaroli and Saita55 also found a four-factor structure of the W-DEQ, and although the four domains were named with slightly different labels than those used by Johnson & SladeReference Johnson and Slade60, the four factors were considerably similar and had a high degree of conceptual overlap. In this best-evidence synthesis two dimensions of pregnancy-specific anxiety, namely Fear of labour and delivery and Negative feelings towards childbirth (corresponding to Lack of positive anticipation in Fenaroli & SaitaReference Fenaroli and Saita55), were thus found to exhibit strong evidence of being psychometrically sound in assessing this specific aspect of antenatal anxiety. A third dimension (Fear for baby's health) showed moderate strength of evidence as, although it was identified in two studies,Reference Fenaroli and Saita55, Reference Johnson and Slade60 contrasting results were found in another study.Reference Wijma, Wijma and Zar73

PRAQ-R and PRAQ-R2

This pregnancy-specific anxiety measure is composed of ten items assessing various manifestations of anxiety related to a current pregnancy. Each item asks about feelings at the present time and has five response options ranging from ‘never’ to ‘very often’. Its original version (PRAQ)Reference Van den Bergh94 consisted of 58 items and was developed based on previous anxiety measures.

The first study testing the psychometric properties of the PRAQ was carried out by Huizink and colleaguesReference Huizink, Mulder, Robles De Medina, Visser and Buitelaar28 who initially tested a revised, 34-item version (PRAQ-RReference Huizink, Mulder, Robles De Medina, Visser and Buitelaar28) of the original PRAQ on 230 nulliparous women. The authors’ aim was to examine the factorial structure of the PRAQ-R and test the hypothesis that pregnancy-specific anxiety could be differentiated from general anxiety by comparing STAI and PRAQ-R scores. They found that only between 8 and 27% of the PRAQ-R variance was accounted for by the index of general anxiety at different time points during pregnancy, with no linear association found between the two measures. This was interpreted as evidence of the distinctiveness of the pregnancy-specific anxiety constructReference Huizink, Mulder, Robles De Medina, Visser and Buitelaar28 and highlighted once more that measures of general anxiety cannot be accurately used to identify women experiencing fears and worries specific to pregnancy.

The authors initially conducted EFA and removed a number of items because of high error variance, resulting in a final version comprising ten items (PRAQ-R). A subsequent CFA revealed that a solution with three factors provided the best fit to the data, with the three identified factors labelled by the researchers ‘Fear of giving birth’ (three items), ‘Fear of bearing a physically or mentally handicapped child’ (four items) and ‘Concern about one's appearance’ (three items). All individual items loaded on one of the factors above the cut-off of 0.63, except for one item (0.50), ‘I am worried about not being able to control myself during labour and fear that I will scream’. Similarly to the approach used for the W-DEQ and discussed above, we considered the whole factors rather than individual items making up a given factor.

Two further studiesReference Huizink, Delforterie, Scheinin, Tolvanen, Karlsson and Karlsson31, Reference Westerneng, de Cock, Spelten, Honig and Hutton33 included here tested the measurement properties of the PRAQ-R, and both replicated the previous finding of a three-factor structure of the PRAQ-R by means of CFA. As the original participants of the ten-item PRAQ-R were exclusively composed of nulliparous women, Westerneng and colleaguesReference Westerneng, de Cock, Spelten, Honig and Hutton33 aimed to test the factorial stability of the three-factor solution of the PRAQ-RReference Huizink, Mulder, Robles De Medina, Visser and Buitelaar28 on a large (n > 6000) data-set of both nulliparous and parous women. This involved the deletion of item 8 ‘I am anxious about the delivery because I have never experienced one before’, as it was not suitable for use with women who had already experienced childbirth. CFA confirmed the same three-factor structure of the original ten-item PRAQ-R with good indexes of fit to the data for both nulliparous and parous women.

Three factors were also found in a recent studyReference Huizink, Delforterie, Scheinin, Tolvanen, Karlsson and Karlsson31 that replaced item eight of the original PRAQ-R with the more generic ‘I am anxious about the delivery’ in order to preserve a ten-item scale while making it appropriate for all pregnant women irrespective of parity (PRAQ-R2)Reference Huizink, Delforterie, Scheinin, Tolvanen, Karlsson and Karlsson31. All item loadings were once more above 0.63 (range: 0.70–0.93) except for two items, ‘I am worried about not being able to control myself during labour and fear that I will scream’, similarly to Huizink and colleagues,Reference Huizink, Mulder, Robles De Medina, Visser and Buitelaar28 and ‘I sometimes think that our child will be in poor health or will be prone to illnesses’.

In summary, across the three studies examined hereReference Huizink, Mulder, Robles De Medina, Visser and Buitelaar28, Reference Huizink, Delforterie, Scheinin, Tolvanen, Karlsson and Karlsson31, Reference Westerneng, de Cock, Spelten, Honig and Hutton33 eight items from the PRAQ-R were found to consistently have high loadings on one of three factors (i.e. pregnancy-specific anxiety domains). These three pregnancy-specific anxiety domains, namely ‘Fear of giving birth’, ‘Fear of bearing a physically or mentally handicapped child’ and ‘Concern about one's appearance’, were all identified in studies of good or excellent methodological quality, thus providing strong evidence of being accurate indicators of pregnancy-specific anxiety.

Discussion

There are several important findings to this study. First, this review has identified a number of anxiety items and domains from existing self-report scales with demonstrated psychometric value when used to assess symptoms of anxiety in pregnant women. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to analyse the content of self-report anxiety measures used in the antenatal period and provide recommendations for the accurate assessment of maternal antenatal anxiety based on a systematic synthesis of published psychometric data.

A second, significant finding of this paper is that it highlights the scarcity of studies reporting psychometric properties of scales employed to measure anxiety in pregnancy. A considerable number of studies using self-report scales to assess antenatal anxiety were not included in this review as no measurement properties of the scale used were reported. It would appear that in most cases researchers have selected a given anxiety measure only based on its widespread use and good psychometric properties in the general population.Reference Brunton, Dryer, Saliba and Kohlhoff36 However, assuming that the measurement properties of a psychological scale developed for the general population are preserved in pregnancy is incorrect for various reasons discussed earlier in this paper (i.e. undue emphasis on somatic symptoms, lack of validated cut-off scores and norms for pregnant populations, role of pregnancy-specific anxiety).

A further limitation of the literature is that only a dearth of studies located by this review (n = 5)Reference Grant, McMahon and Austin8, Reference Matthey, Valenti, Souter and Ross-Hamid67, Reference Simpson, Glazer, Michalski, Steiner and Frey70, Reference Tendais, Costa, Conde and Figueiredo72, Reference Zhong, Gelaye, Zaslavsky, Fann, Rondon and Sanchez74 validated a measure against a reference ‘gold’ standard such as a structured diagnostic interview. Testing a scale against a reference standard provides evidence of the screening accuracy of a measure, also referred to as its criterion validity, arguably the single most important aspect of psychometric validation of a scale.Reference DeVellis48

Perhaps even more surprisingly, only two studiesReference Simpson, Glazer, Michalski, Steiner and Frey70, Reference Zhong, Gelaye, Zaslavsky, Fann, Rondon and Sanchez74 were identified that examined the psychometric properties of the GAD-7 in a pregnant population, and only oneReference Zhong, Gelaye, Zaslavsky, Fann, Rondon and Sanchez74 was found to have satisfactory methodological quality. As previously reported, the GAD-2 (i.e. the initial two questions of the GAD-7) is the measure currently recommended by NICE in the UK to screen for anxiety in pregnant women, followed by administration of the GAD-7 if a woman scores three or higher on the GAD-2.6 The only methodologically robust study providing psychometric information on the GAD-7 in a pregnant populationReference Zhong, Gelaye, Zaslavsky, Fann, Rondon and Sanchez74 was also somewhat limited by focusing exclusively on the screening accuracy of the GAD-7 for generalised anxiety disorder, without providing any evidence of its screening ability for other anxiety disorders in pregnancy. Furthermore, subanalyses to assess the screening ability of the GAD-2 as opposed to the full GAD-7 were not conducted, thus leaving unanswered the question of whether the GAD-2 can be used as an ultra-brief screening scale for problematic anxiety symptoms in pregnancy, as per recent guidelines.6

Key best-evidence findings

Eight self-report measures were considered in the synthesis of the best available evidence presented above. One further scale located by this review (Pregnancy Anxiety ScaleReference Levin65) was not examined at the best-evidence stage as the single study reporting its psychometric properties was rated poor for its methodological quality.Reference Levin65

The key findings regarding anxiety items and domains identified as accurate indicators of antenatal anxiety, as discussed in the Results, are summarised here. A complete list of all the identified anxiety items and domains is also presented in the supplementary Table 2. Furthermore, a table summarising all the correlations between scales included in the review is available in supplementary Table 3.

Items assessing excessive, generalised worry were found to be psychometrically sound in the antenatal period in the EPDS, HADS-A, BMWS, GAD-7 and STAI-S. Overall, there was strong evidence of the psychometric robustness of items measuring the domain of worry, with consistent findings in multiple studies of good or excellent quality. Since excessive worry is essentially a cognitive symptom, it could be argued that it is less susceptible to the physical and physiological changes of pregnancy, and it remains thus a good indicator of problematic anxiety in pregnancy as it is in the general population.

A second anxiety domain that showed good evidence of its psychometric soundness in pregnant populations concerned items tapping into symptoms of fear or panic. Feelings of fear are another important component of different anxiety disorders, including panic disorder, agoraphobia, social anxiety disorder and specific phobia.22, Reference Craske, Rauch, Ursano, Prenoveau, Pine and Zinbarg95 In this review, items assessing the fear/panic domain were identified as psychometrically sound for use in pregnancy in various scales, including the HADS-A, the EPDS and several pregnancy-specific anxiety scales.

Other specific symptoms identified by this review showed moderate evidence of their screening ability in the assessment of antenatal anxiety. These included being excessively self-critical (EPDS, item 3), feeling upset (STAI-S, item 6) and the experience of nervous or motor tension (STAI-S, item 3). Although these symptoms may not appear to be specific to anxiety disorders, these findings are in line with the well-established tripartite model of anxiety and depression. This model postulates that depressive and anxiety disorders share a common component of general emotional distress, and the symptoms above can be categorised as manifestations of general distress, which can be present in both depressive and anxiety symptomatology.Reference Clark and Watson96

In relation to anxiety symptoms specifically related to pregnancy, fear of childbirth was shown to be a good indicator of pregnancy-specific anxiety. Specifically, pregnancy-specific anxiety symptoms of fear related to giving birth exhibited strong evidence of their psychometric value in the W-DEQ (several items) and the PRAQ-R (two items related to fear of childbirth).

Items assessing persistent worries specifically related to pregnancy also showed good psychometric properties in the CWS, the W-DEQ and the PRAQ-R. The worries with the strongest evidence to support their screening accuracy related to concerns regarding the health or safety of the baby and the possibility of miscarriage. Other worries, including being in hospital and worrying about future parenting showed only moderate evidence of their screening value (see supplementary Table 2). It may be argued that most women are likely to experience some degree of concern regarding these aspects of pregnancy, but that in women experiencing clinical levels of anxiety these worries may be more intense or persistent (i.e. higher severity or frequency).

Strengths and limitations

The present review has a number of strengths. Only studies with good or excellent methodological quality as determined by the COSMIN checklistReference Terwee, Mokkink, Knol, Ostelo, Bouter and de Vet45 were included in the best-evidence synthesis, thus guaranteeing that the conclusions reached were only based on the strongest evidence available. We also used a comprehensive search strategy that was devised to locate studies testing the psychometric properties of both general anxiety scales and pregnancy-specific anxiety measures, unlike previous reviews that were focused mostly or exclusively on general anxiety or pregnancy-specific anxiety scales.Reference Meades and Ayers35, Reference Brunton, Dryer, Saliba and Kohlhoff36 A second reviewer independently checked a sample of studies, both in the initial phase of screening of titles and abstract and for the quality assessment of included studies, as per best practice recommendations for systematic reviews.37 The review was reported according to the PRISMA reporting guidelinesReference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman39 (see supplementary Table 4).

Several limitations also have to be acknowledged. Searches were limited to research articles in English and restricted to publications from 1991 onwards, this being the year when the first pregnancy-specific anxiety scale was developed. The generalisability of the review findings may also be somewhat limited by the fact that we did not include studies from countries with substantial cultural differences compared with the UK (i.e. Asian and African countries) for which cultural equivalence of psychological symptoms cannot be assumed.Reference Gunay and Gul97, Reference Takegata, Haruna, Matsuzaki, Shiraishi, Murayama and Okano98

Implications and future directions

The accurate identification of women experiencing high levels of anxiety symptoms in pregnancy is important and deserves clinical attention for several reasons. Whereas postnatal depression has been the focus of most research in perinatal mental health in the past decades,Reference Austin21, Reference Goodman, Chenausky and Freeman24 there is now a substantial body of research indicating that anxiety in pregnant women is common and is associated with increased risk for negative maternal and child outcomes.Reference Dunkel-Schetter, Lobel, Revenson, Baum and Singer3, Reference Dunkel Schetter and Tanner32, Reference Gavin, Meltzer-Brody, Glover, Gaynes, Milgrom and Gemmill99 In the UK, the Royal College of General Practitioners has identified perinatal mental health as a clinical priority100 and a recent report from the London School of Economics has estimated the costs of neglecting perinatal mental health problems in the UK to be a striking figure of £8.1 billion for every annual cohort of women, with approximately three-quarters of this cost related to the adverse long-term impact on children.Reference Bauer, Parsonage, Knapp, Iemmi and Adelaya101

Among the range of perinatal mental health problems that women can experience, anxiety disorders have the highest prevalence.Reference Dennis, Falah-Hassani and Shiri1 Consequently, a number of authors in recent years have advocated the use of a brief scale for the universal screening of antenatal anxiety.Reference Brunton, Dryer, Saliba and Kohlhoff36, Reference Biaggi, Conroy, Pawlby and Pariante102 To the best of our knowledge, no anxiety scales have been developed that are specific to the antenatal period and take into account both general and pregnancy-specific anxiety symptoms. Most studies have used measures of general anxiety, but the clinical importance of including screening for pregnancy-specific anxiety symptoms is supported by studies indicating that pregnancy-specific anxiety may be a better predictor of adverse birth and child development outcomes than general anxiety during pregnancy.Reference Blackmore, Gustafsson, Gilchrist, Wyman and O'Connor34, Reference Davis and Sandman103

Future research is needed to conduct robust psychometric studies of existing measures in sufficiently large samples and ideally including validation against a reference standard. The development of a new anxiety scale specifically constructed for use in pregnancy and that takes into account both general anxiety and symptoms of pregnancy-specific anxiety would also be highly desirable.

In sum, despite the research literature on prevalence, risk factors and treatment of antenatal anxiety having decisively grown in recent years,Reference Dennis, Falah-Hassani and Shiri1, Reference Grant, McMahon and Austin8, Reference Marchesi, Ossola, Amerio, Daniel, Tonna and De Panfilis104 this review clearly points out how evidence regarding the screening performance of anxiety scales for use in pregnancy, including the one currently recommended by NICE, remains insufficient. The lack of measures with a sufficient evidence base constitutes a considerable barrier to the identification of pregnant women experiencing problematic anxiety symptoms, the initial step if they are to be offered the appropriate support or treatment. This is, in turn, an important missed opportunity for early prevention of negative health outcomes for women and their children. This review improves the current understanding of anxiety symptomatology in pregnant women and may contribute to provide the theoretical basis for the development of a psychometrically robust screening scale for antenatal anxiety.

Funding

A.S. was supported by a Doctoral Training Fellowship from the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health Directorates (DTF/15/03).

Acknowledgements

We thank Alex Pollock (Nursing, Midwifery and Allied Health Professions Research Unit, Glasgow Caledonian University) for her contribution to the design of the study.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2018.75.

Appendix

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.