Introduction

In 2015, more than one million refugees, mainly from the Middle East and North Africa, came to Europe. Ever since, the refugee question has been high on the European agenda, closely monitored by the mass media – and highly politicized. Far-right parties in the EU have used discourses of threat and fear of the refugees to gain political influence and electoral success (see e.g., Feischmidt Reference Feischmidt2020). With few exceptions, research on the so-called 2015 European “refugee crisis” has generally focused on European experiences and responses (see Greussing and Boomgaarden Reference Greussing and Boomgaarden2017; Vollmer and Karakayali Reference Vollmer and Karakayali2018; Hovden, Mjelde, and Gripsrud Reference Hovden, Mjelde and Gripsrud2018). This article expands the focus, arguing that it is also important to study how the 2015 “refugee crisis” has influenced debates in countries not directly affected. Here, I offer an exploratory study of media representations in the Russian Federation. Some observers have argued that leaders such as Vladimir Putin (CNBC 2016) and Aleksandr Lukashenko (Deutsche Welle 2021) have used refugees as a “hybrid weapon” against the EU. This warrants closer examination of how the European “refugee crisis” has been interpreted in countries beyond the EU and the West.

Media representations of refugees carry meaning that goes beyond descriptions of persons who fit the legal criteria drawn up by the 1951 Refugee Convention and 1967 Protocol (UNHCR 2010).Footnote 1 These representations reflect other aspects, such as political views on immigration policy and the assignment of responsibility and blame, positioning the Self – an imagined “us” – in relation to ideas about “them.”

Russian discourse offers a relevant vantage point for studying media representations of the “refugee crisis.” With its unique geographical location between the East and the West, Russia has had an ambivalent relationship with the West throughout history. Contrasting ideas about Russia as part of Europe, and of Europe as Russia’s “Other,” have always been part of Russian identity construction (Neumann Reference Neumann2017). Are representations of the “refugee crisis” in Russian media similar to or different from representations in the European media? An important contextual factor is that the European “refugee crisis” has not affected Russia directly. Russia has not been a final destination for any of the refugee routes, nor has it contributed much in terms of burden-sharing as regards the recent influx to Europe.Footnote 2 Even so, I argue that Russian commentators have used representations of the crisis strategically to position Russia vis-à-vis the West.

Studies of media representations of the European “refugee crisis” have generally concentrated on the European media: German (Vollmer and Karakayali Reference Vollmer and Karakayali2018), British (Goodman, Sirriyeh, and McMahon Reference Goodman, Sirriyeh and McMahon2017), Polish (Krzyżanowski, Triandafyllidou, and Wodak Reference Krzyżanowski, Triandafyllidou and Wodak2018; Krzyżanowska and Krzyżanowski Reference Krzyżanowska and Krzyżanowski2018), Austrian (Greussing and Boomgaarden Reference Greussing and Boomgaarden2017; Rheindorf and Wodak Reference Rheindorf and Wodak2018), and Scandinavian (Hovden, Mjelde, and Gripsrud Reference Hovden, Mjelde and Gripsrud2018). Little has been published in English about Russian interpretations of the crisis (however, see Kalsaas Reference Kalsaas2017; Braghiroli and Makarychev Reference Braghiroli and Makarychev2018; Moen-Larsen 2020a). The focus has been on the general media discourse on refugees and on how Russia has used the “refugee crisis” to reenter the European political scene. In contrast, this article offers an in-depth study of elite discourse based on opinion pieces and interview articles in three major Russian newspapers, focusing on the interrelation between the positioning of refugees, Russia, and the West.

Media representations in general, and elite discourses in particular, carry symbolic and persuasive power. Analyzing the discourses articulated by elites in Russian newspapers is an effective way to gain insights into Russian meaning-production on the “refugee crisis” and Russia’s identity in that context. This study sheds light on an aspect not addressed by earlier research – representations of the refugee as a victim of interventionism and democratization processes initiated by the West in the Middle East and North Africa. More generally, the study adds to the literature on discursive construction of identity and difference.

Studies of Media Representations of the European “Refugee Crisis”

This article both builds on findings from relevant studies and contributes to this body of literature by delving into an under-researched case: Russia. In studies of media representations of the 2015 “refugee crisis,” the refugees themselves are rarely in the center of the analysis: the focus is on macro-processes, such as politization and medialization of migration, social construction of a crisis, and the potential breakdown of European solidarity. Like other studies of media representation of asylum seekers and refugees (see, e.g., Lueck, Due, and Augoustinos Reference Lueck, Due and Augoustinos2015; Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, ter Wal, Lipiński, Fabiszak and Krzyżanowski2013; Leudar et al. Reference Leudar, Hayes, Nekvapil and Baker2008), most research on the 2015 “refugee crisis” finds negative images of refugees in the media. For example, in Poland, refugees and asylum seekers are framed as “a threat” and as “profoundly different” from the Polish “native” population (Krzyżanowski Reference Krzyżanowski2018, 92). Such representations of refugees as threats are part of a security discourse that has been identified across Europe – for example, in Austria (Greussing and Boomgaarden Reference Greussing and Boomgaarden2017; Rheindorf and Wodak Reference Rheindorf and Wodak2018), Greece (Boukala and Dimitrakopoulou Reference Boukala and Dimitrakopoulou2018), Serbia and Croatia (Sicurella Reference Sicurella2018), and Slovenia (Vezovnik Reference Vezovnik2018).

Anna Triandafyllidou (Reference Triandafyllidou2018) notes two main frames identified by research on representations of the 2015 “refugee crisis”: moralization and threat. The moralization frame blames wars for the “refugee crisis,” views refugees as victims, refers to common European values, appeals to solidarity and the “obligation of Europe to stand true to its humanitarian values of providing protection to those who are persecuted, to show its humanity” (Triandafyllidou Reference Triandafyllidou2018, 211). In contrast, the threat frame represents the wave of asylum seekers as unmanageable and unpredictable, and holds that “what migrants-refugees ‘achieve’ comes at the expense of the natives who welcome them” (Triandafyllidou Reference Triandafyllidou2018, 212). Researchers have noted a change – a discursive shift (Krzyżanowski Reference Krzyżanowski2018, 78) – in media portrayals of the refugees during 2015 and early 2016, when the moralization frame was replaced by a threat frame (see Vollmer and Karakayali Reference Vollmer and Karakayali2018; Goodman, Sirriyeh, and McMahon Reference Goodman, Sirriyeh and McMahon2017; Hovden, Mjelde, and Gripsrud Reference Hovden, Mjelde and Gripsrud2018). According to Krzyżanowski, Triandafyllidou, and Wodak (Reference Krzyżanowski, Triandafyllidou and Wodak2018, 7), a main discursive shift was the “ever-more obvious endorsement of anti-immigration rhetoric and/or of a harshened stance on openness toward refugees.”

Also, studies of Russian media have identified the reoccurrence of a threat frame and overall negative representations of refugees from the Middle East and North Africa (e.g., Kalsaas Reference Kalsaas2017; Khismatullina, Garaeva, and Akhmetzyanov Reference Khismatullina, Garaeva and Akhmetzyanov2017), although a humanitarian discourse, compatible with the moralization frame, has also been identified (Moen-Larsen 2020a). On the macro-level, studies of Russian representations of the 2015 European “refugee crisis” and attitudes towards this crisis also say something about Russian ideas about Europe. The humanitarian aspect of European migration policy is perceived either as a form of complacency that threatens European security, or as a cover-up for ulterior self-serving motives (Simon Reference Simon2018, 12). Papiya (Reference Pipiya2016, 162) argues that these negative attitudes toward refugees and EU refugee reception policies are connected to negative attitudes toward migrants in Russia and Russia’s anti-European, anti-Western position that has emerged from the disagreements between Russia and the West about Ukraine and Syria.

Thus, research on media representations of the “refugee crisis” has explored the connection between primarily negative images and complex political processes. Here, I will discuss how authors of opinion pieces and interview articles use the discourse about the European “refugee crisis” to legitimize Russia’s actions in the field of international relations. Whereas previous research discusses the connection between ideas about refugees, Russia, and the West only indirectly, this article places the identity debate at the core of the analysis.

Discourse Theory

This article is about communication and meaning-making processes in society. As words and practices are closely connected, it is essential to study what the media write about migrants and refugees. Discourse analysis is useful for scrutinizing written and spoken words and revealing the effects of “naturalizing” one social reality rather than another (Dunn and Neumann Reference Dunn and Neumann2016, 2). “Discourse” can be broadly defined as a “particular way of talking about and understanding the world (or an aspect of the world)” (Jorgensen and Phillips Reference Jorgensen and Phillips2002, 1). Based on this definition, a discourse about refugees is a particular way of speaking about one group of people and interpreting phenomena that involve refugees within a specific cultural and historical context. All discourses about refugees within a given society are part of the social construction of the meaning of “refugee.” “Social constructs come with a prescribed treatment plan: victims need to be helped, the sick need healthcare, children should attend school, adults should work and serve as a resource – whereas terrorists should be neutralised and criminals incarcerated” (Moen-Larsen 2020a, 237). Social constructions enable policies and practices – and are therefore important objects of research.

My theoretical framework is discourse theory as formulated by Laclau and Mouffe (Reference Laclau and Mouffe2014, 91), who define a discourse as “a structured totality” from the “articulatory practice,” which is “any practice establishing a relation among elements,” for example, by speaking or writing. However, the practice of articulation does not consist solely of linguistic phenomena: it also penetrates institutions, rituals, and practices that structure discursive formations (ibid., 95). For Laclau and Mouffe, “any discourse is constituted as an attempt to dominate the field of discursivity, to arrest the flow of differences, to construct a centre” (ibid., 98–99). Various positions within a discourse are “moments,” whereas “nodal points” are privileged discursive points of this partial fixation (ibid., 91, 99). Nodal points give meaning to other moments within a discourse. For example, discourse theory sees “social class” as a nodal point in Communist discourse. Concepts such as “struggle” and “consciousness” are moments that gain meaning from their connection to “social class.”

According to Jorgensen and Phillips (Reference Jorgensen and Phillips2002, 40), one aim of discourse analysis is to point out “the myths of society as objective reality that are implied in talk and other actions.” The definition of a “myth” within the discourse theoretical framework differs from common definitions that see a myth as a symbolic narrative or a legend. For discourse theorists, myths refer to a totality while at the same time providing an image and a feeling of unity (Laclau Reference Laclau1990, 99), as with, for example, “society” or “country.” Although “society” does not exist as an objective reality, in our daily lives we act as if it does. According to Jorgensen and Phillips (Reference Jorgensen and Phillips2002, 40), “the myth, ‘the country,’ makes national politics possible and provides the different politicians with a platform on which they can discuss with one another.” Here, I see a parallel to Anderson’s (Reference Anderson1991) concept of the nation as an imagined community – “the nation” is a myth. According to Laclau (Reference Laclau1990, 61, 66), “the effectiveness of myth is essentially hegemonic” because it manages hegemonically to impose a particular social order. To put it differently, “myth overcodes an entire sign system onto a single denotation […]. In particular it is a powerful agent of the naturalization of meaning, and is often a site of struggles over meaning” (Twaites, Davis, and Mules Reference Twaites, Davis and Mules2002, 69).

In this article, I have chosen to use the concept of “myth” to distinguish between representations of individuals (refugees) and representations of states or other geographical entities (Russia or Europe). Social actors represent their societies and nations in contrast to other societies and nations, and I view such representations as mythical. Thus, I analyze representations of Russia as myths. People view Russia as an objective reality and continuously rearticulate elements that infuse “Russia” with meaning. Antagonisms reveal the taken-for-grantedness of hegemonic ideas about Russia. Is, for example, Crimea part of “Russia”? The contradictory answers to this question indicate the ongoing struggle over what “Russia” is culturally and geographically.

The articulation of particular images of others is also a question of identity. Laclau and Mouffe (Reference Laclau and Mouffe2014, 97, 101) view identities as relational and constituted by subject positions within a discursive structure. According to Davies and Harré (Reference Davies, Rom, Stephanie and Yates2007, 262), “the constitutive force of each discursive practice lies in its provision of subject positions. An individual’s experience of their identity can only be expressed and understood through discourse.” They use the term “positioning” to underline that identity is shaped through active cooperation between agents. When we speak of others and ourselves in particular ways, we take part in constructing subject positions. For example, we often construct in- and out-groups through positive self-presentation and negative presentation of others (Richardson and Wodak Reference Richardson and Wodak2009; Wodak Reference Wodak, Culpeper, Kerswill, Wodak, McEnery and Katamba2009, 582). We position others to make them understandable to us – and in positioning others, we position ourselves.

In his study of Russia’s centuries-old debate about Europe, Neumann claims, “the idea of Europe is the main ‘Other’ in relation to which the idea of Russia is defined” (Neumann Reference Neumann2017, 3). Thus, an analysis of Russian discourse about the European “refugee crisis” can illustrate the complexity of identity construction. How social actors position refugees in the discourse and the ideas they articulate about Europe in the context of the 2015 “crisis” also reflects how they see themselves and Russia. In this article, I show how one word – “refugee” – can contribute to unpacking a complex set of ideas and contested mythical representations of Russia, Europe, and the West that circulate in Russian society.

Data from Izvestiya, Novaya Gazeta, and Rossiiskaya Gazeta

According to Freedom House (2021), the Russian government controls all the national television networks, and many radio and print outlets. A handful of independent outlets still operate, most of them online and constantly under threat of closure. This study treats Russian newspapers as channels that produce, reproduce, and disseminate discourse. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge the differing points of departure for media texts on the “refugee crisis” produced in Western Europe and media texts produced in Russia.

This article analyzes data gathered from three Russian newspapers with nationwide circulation: Izvestiya (Iz), Novaya gazeta (NG), and Rossiiskaya gazeta (RG). Izvestiya is a daily newspaper that publishes reports on current affairs in Russia and abroad. In my data sample, Izvestiya represents mainstream pro-government discourse. Novaya gazeta is known for its government-critical position and investigative reporting. It was, until March 2022, one of the few remaining newspapers that represented the critical opposition in Russia. In 2021, its editor, Dmitrii Muratov, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his “efforts to safeguard freedom of expression, which is a precondition for democracy and lasting peace” (Nobel Peace Prize 2021).Footnote 3 Finally, Rossiiskaya gazeta is the official newspaper of the government of the Russian Federation and thus represents the official discourse in my data sample. In 2015, the year the analyzed texts were published, circulation figures (as of September) for the printed version of Izvestiya were 73,520; 216,550 for Novaya gazeta; and 159,118 for Rossiiskaya gazeta. While these figures may seem quite modest, all three newspapers have a strong online presence and a high citation rate.Footnote 4 Indeed, since 2015, the three have consistently been ranked among the ten most-cited newspapers in Russia.Footnote 5

I have used the databases East View Information Services and Integrum World Wide to identify opinion pieces and interview articles that mention refugees from the Middle East and North Africa and that appeared in the print versions of Izvestiya, Novaya gazeta, and Rossiiskaya gazeta in the period January–December 2015.Footnote 6 The printed versions of the newspapers were chosen because of their accessibility and the possibility of downloading large amounts of text, based on word searches. As all articles available in the print version of the three newspapers can also be read online, the potential readership of the material is not limited to the readers of the physical edition. Further, I chose to focus on opinion pieces and interview articles because these reflect the personal opinion of a specific author or interviewee, or the position of an organization or government that the writer represents.

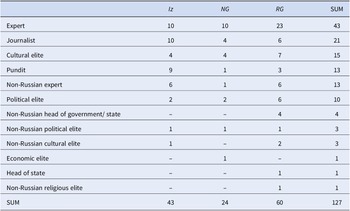

The authors and intervieweesFootnote 7 in my data are drawn from the Russian and non-Russian elite (see Table 1). Yablokov (Reference Yablokov2018, 106) found that the use of non-Russian experts to provide legitimacy to controversial statements is a distinct characteristic of the official Russian discourse: “The fact that these experts from the West had similar ideas to those in Russia provided Russian journalists’ reports with pseudo-objective appearance, as though they were presenting how the events were seen from abroad” (Yablokov Reference Yablokov2018, 106). I have chosen to keep the texts with foreign authors as part of the analysis because, like all the other texts in the data sample, they are part of the construction of the meaning of the “refugee crisis” in Europe for Russian audiences.

Table 1. Authors of opinion pieces and intervieweesFootnote 8

I concur with Sicurella (Reference Sicurella2018, 62) who argues that public intellectuals and other elites have symbolic power to shape people’s beliefs and attitudes. Not all societal actors can publish their opinions in a newspaper, but elites have access to means of mass communication and therefore the opportunity to make their representations of reality available to a large readership. That makes it important to scrutinize the discourse articulated by elites.

The data sample includes 43 texts from Izvestiya (39 opinion pieces, 4 interview articles), 24 from Novaya gazeta (20 opinion pieces, 4 interview articles), and 60 from Rossiiskaya gazeta (39 opinion pieces, 21 interview articles). The great majority of texts – 116 of 127 – were published between September and December 2015. Several events can explain this heightened focus on refugees after September 2015: the appearance of the picture of the drowned three-year old refugee Aylan Kurdi in international news media, Russia’s involvement in the conflict in Syria, and the November 13 terrorist attacks in Paris.

I have used NVivo to sort and code the data. In the coding, I have focused on five core points: overarching theme, author of the text/interviewee, subject position “refugee,” representation of Russia, and representations of Europe/the EU, USA, or the West in general. The top five recurring themes in the data are international relations (40 texts), the “refugee crisis” (23 texts), the conflict in Syria (17 texts), culture (e.g., literature, film, books) (9 texts), and terrorism in France (8 texts).Footnote 9 Throughout the analysis, I focus on the relationship between ideas about “us” and ideas about “them” – “others” who are different from “us” and who define “us.” Ideas about “us” are examined in connection with how the myth “Russia” is reproduced in my empirical material. Ideas about “others” are representations of refugees and articulations of the myths of “the West,” “Europe,” and “the USA.”

Representations of Refugees

The authors of the opinion pieces and the interviewees in my data often use the term “refugee” without any further explanation. For example, in 27 texts, “refugee” is used in referring to a topic of conversation or a news item. However, the articulations of the subject position “refugee” that I have identified in most texts are consistent with the findings of the research cited above. Commentators in the two pro-government newspapers Izvestiya and Rossiiskaya gazeta articulated mainly negative representations of refugees coming to Europe, representing the subject position “refugee” as a threat to the EU and to Europe, and as part of security discourse (Iz 12, RG 24). In contrast, only two commentators in the liberal opposition newspaper Novaya gazeta did so.

When representing refugees as a threat to Europe, authors combine the nodal point “refugees” with moments such as “Europe,” “crisis,” “threat,” “illegals,” “barbarians,” “flood,” “uncontrolled flow,” “invasion,” and “borders.” These moments signal a security discourse where the refugees are represented as a danger against which Europeans must protect themselves: “At this moment there are hundreds of thousands of people at the gates of Europe, they are not enemies of the Europeans but have nevertheless become a serious threat to the European Union” (non-Russian political elite, op-ed, Iz, September 23); “The migrant invasion in Europe is the worst challenge to Europe in its entire history” (pundit, op-ed, Iz, September 14); “the illegals are weakening the Old World” (expert, op-ed, RG, April 21); “The EU countries are experiencing a total flooding by uninvited strangers” (expert, op-ed, RG, September 11); and with the large numbers of refugees coming to the EU, “Europe will be brought to its knees” (cultural elite, op-ed, NG, November 16).Footnote 10

Further, and as part of a security discourse, some authors, primarily in Rossiyskaya gazeta, represent refugees as a security threat with reference to moments such as “terrorist,” “terrorism,” and the “Islamic State” (IS) (10 texts in RG, 4 in Iz, 2 in NG). Sergey Ivanov, Chief of Staff of the Presidential Administration, asks rhetorically, “Do you think that there are no so-called ‘sleepers’ among them [the refugees]? ‘Sleeping’ agents and terrorists who come to the Old World to establish themselves quietly, to hide and to wait?” (political elite, op-ed, RG, October 20). Aleksandr Lebedev, a well-known Russian businessman, compares IS with a cancerous tumor that is spreading across the continents, “assisted by the flows of countless refugees with whom the bearers of the ideology of hatred penetrate Europe and America” (economic elite, op-ed, NG, September 14).Footnote 11

Also, traces of a humanitarian discourse emerge in my data (16 texts in RG, 11 in NG, 5 in Iz). Moments the commentators articulate together with the nodal point “refugee” range from “war” and “death” to “humanism” and “human being.” Indeed, some authors position the refugees as the victims of war or violent conflict – for example, as “war-bitten refugees” (journalist, op-ed, NG, September 23, 2015). However, some of these are non-Russian voices referred to in the Russian newspapers: for example, researchers from the German Institute for International and Security Affairs are reported as saying that the violence in Syria will continue to push people out of the country (non-Russian experts, op-ed, NG, December 18). In an interview, Vygaudas Ušackas, EU Ambassador to Russia, stated: “We [in the EU] follow the principle of humanism: we need to help those who flee from war or other threats to life, and respect the human dignity of each human being” (non-Russian political elite, interview, NG, September 14). In contrast to the image of refugees as a threat and Europe as threatened, these non-Russian authors in Novaya gazeta represent the refugees as threatened and Europe as a humanitarian actor that can provide shelter to them.

Other authors represent refugees as victims, as shown by images of those who drowned at sea or suffocated in a trailer on their journey through Europe. “People who some years ago were useful members of society, heads of families, mothers with children, who built, plowed, and gathered olives have turned into human dust, driven along the roads, or into fish food” (journalist, op-ed, Iz, April 22). Some invoke the pathos-laden victim trope of “women and children” – for example, “A refrigerated truck containing 71 bodies of refugees from Syria was found on the side of the Autobahn southeast of Vienna. Apparently, these people died from suffocation: and there were women and children among them” (expert, op-ed, NG, August 31). The author of this text argues that these Syrian victims were not accorded the mourning they deserved in Austria, and that this reflects “the general wariness or even anger of Europeans towards the uninvited guests” (ibid.) Also here, victim representations are used to construct an idea about Europe – but in contrast to the image of Europe as a successful humanitarian actor, Europe is now represented as cold and unfeeling toward the refugees.

What most clearly sets the Russian media discourse apart from the refugee-representations found in other European media is the representation of the refugee as a victim of Western interventionism and the democratization processes in the Middle East and North Africa (8 texts in RG, 6 in Iz). Here, commentators combine the representation of the refugee as a victim with moments like “the West,” “democratization,” and “the Middle East” – all of them part of a geopolitical discourse rather than the above-mentioned humanitarian discourse. In the words of the conservative pundit Egor Kholmogorov:

Today’s refugees come from until recently relatively prosperous countries in the Middle East and North Africa, which were destroyed by the “Arab Spring” initiated by the United States and enthusiastically supported by the European leaders. Europe is dealing with the fruits of its own labor and its own stupidity. […] The entire stream of refugees sailing from Libya to Italy and making their way through Turkey and Greece to Hungary and then to Germany are people whose problems Sarkozy, Hollande, and Merkel are directly responsible for, together with Obama. (Pundit, op-ed. Izvestiya, September 1)

Likewise, Konstantin Dolgov, Commissioner for Human Rights at the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, claims, “these refugee flows are another consequence of the notorious democratization in the Middle East and North Africa region” (political elite, op-ed, RG, July16).Footnote 12

In addition to scrutinizing the written word, it is important to note the gaps in the discourse – what is not said? Above, I mentioned the argument put forward by some Western European and US observers about refugees being used by Russia and Belarus as a hybrid weapon against the EU. However, I do not find this discourse articulated in my data. Although the metaphor of the refugees-as-weapons is a construction rooted in security discourse, it is not part of the Russian security discourse on refugees – it is a construct of actors in the West. This Western discourse securitizes Russia and produces an image of Russia as an antagonist in a hybrid war. Such representations of Russia can be viewed as an extension of other enemy images of Russia originating in the West and some post-Communist countries (Lanoszka Reference Lanoszka2016; Wither Reference Wither2016; Fridman Reference Fridman2018). Thus, the absence of representations of the refugee-as-weapons in my empirical material is quite logical – this way of seeing Russia is foreign to Russians.Footnote 13

In contrast, the representation of refugees as victims of Western interventionism and democratization is a Russian construct: Russian actors position the collective West as a perpetrator, responsible for conflicts in Middle East and North Africa. This illustrates how contrasting representations of refugees and the discourses of which they are part also rearticulate the myth of Russia and the West as each other’s opponents.

Thus, we find three discourses in the empirical material – security, humanitarian, and geopolitical – that elites articulate in discussing refugees in the context of the 2015 “crisis.” The representation of the subject position “refugee” in these discourses must be analyzed in relation to other nodal points. Op-eds and interviews are never “only” about the refugees: they also articulate myths about Russia, Europe, and the West. In the following sections, I discuss such myths in light of these three overarching discourses.

Representations of Russia

Although my criterion in data collection was the use of the word “refugee,” most of the texts were not primarily about refugees as people. The most frequent overarching topic was international relations in general (40 texts). Thus, in addition to saying something about the social construction of the subject position “refugee” in Russian newspapers, my empirical material shows how the commentators rearticulate the myth of Russia as an actor in the field of international relations. The two most frequent representations of Russia are as a partner (27 texts) or as an object of criticism (14 texts). There is a clear divide here, between opinions articulated in Novaya gazeta, on the one side, and in Izvestiya and Rossiiskaya gazeta on the other. Whereas many of those writing in Novaya gazeta voice criticism of Russia, the representations of Russia in Izvestiya and Rossiiskaya gazeta are mostly positive.

The timeframe for this study coincides with the first few months of Russia’s military intervention in Syria, which started on September 30, 2015 (Al Jazeera 2015). Because many refugees who fled to Europe in 2015 came from Syria (UNHCR 2016), several of the texts voice opinions about Russia’s intervention in Syria. Such discussions of Syria are part of the geopolitical discourse mentioned above; the nodal point “Russia” is combined with discursive moments such as “the West,” “Syria,” “Assad,” “Europe,” “USA,” and “the global order.” Those writing in Rossiiskaya gazeta and Izvestiya position Russia as partner to Europe and the West, and to Assad’s regime in Syria. They claim that, by assisting Assad, Russia is helping Europe to deal with the refugee question.

Further, the geopolitical discourse about the conflict in Syria is linked to a security discourse about the global fight against terrorism. Some authors equate siding with Assad with fighting IS terrorism or terrorism in general. For example, the above-mentioned Sergey Ivanov explains Russia’s official position in the following way: “Russia considered it possible to answer the legitimate leadership of Syria to help him [Assad] in the fight against terrorists […], as the situation became intolerable” (political elite, interview, RG, October 20). German political scientist Alexander Rahr claims: “In Syria, Russia seeks to become the leading force of the anti-terrorism alliance” (non-Russian expert, op-ed, RG, October 8).Footnote 14

Several commentators in Izvestiya articulate a myth of Russia as a hero that will protect the world from the chaos caused by the emergence of IS: Russia “warned that this uncontrollable chaos would come […] Russia is doing what she can in order to […] defeat the evil force [IS] that calls into question our entire culture, the entire Christian world” (expert, op-ed, Iz, October 1). Whereas those writing in Izvestiya represent Russia as heroic, commentators in Rossiiskaya gazeta stress Russia as a strategic actor, for example, through references to status and to the “Great Game” in international relations. “Through military operations on the side of Assad, Russia has entered the ‘Great Game’ because it concerns participation in the building of a global world order” (non-Russian expert, op-ed, RG, October 8). By intervening in Syria, Russia has shown that it is a “great power” now “getting up from its knees” (cultural elite, interview, RG, February 26).

Moreover, several writers claim that the West perceives Russia primarily as a threat, or use the expression “Russian threat” (e.g., journalist, op-ed, RG, September 22).Footnote 15 Some commentators connect this “Russophobia” (e.g., pundit, Izvestiya, September 14) with the “erroneous” perception “that Russia’s actions provoked the powerful flow of refugees to Europe” (expert, op-ed, RG, November 25) – a perception that, according to these writers, flourishes in the West. On the contrary, they hold, by intervening in Syria Russia is assisting the world in solving the “refugee crisis”:

Our planes are fighting for Syria, to save it, and to prevent the spread of a terrible black pit […]. By preventing the emergence of a black pit, we are also saving Europe. Because millions of new refugees would pour out of this pit and […] overflow the European world. (Pundit, op-ed, Iz, October 20)

In contrast to the articulations of the myths of Russia as heroic and strategic, commentators in Novaya gazeta are critical of Russia’s actions on the international arena and its geopolitical ambitions. For example, one expert claims that Putin sees himself as the liberator of “not only Europe but the whole world,” and Russia’s imperial ambitions explain why it is meddling in European affairs (expert, op-ed, NG, November 18).Footnote 16 In addition to the geopolitical discourse noted above, those writing in Novaya gazeta articulate a humanitarian discourse when they criticize Russians for their lack of compassion and for expressing contempt towards refugees from the Middle East and North Africa. For example, “Educated Russians openly fear and despise refugees who are fleeing to Europe from war” (pundit, op-ed, NG, September 28); “Almost no one is coming to us from the Middle East, nevertheless [Russians] speak with great contempt of refugees who are not even coming to us” (expert, op-ed, NG, November 16). That author is one of the few who mention the absence of refugees in Russia. Overall, the texts are quiet on the possibility of Russia offering asylum to the refugees.Footnote 17 This indicates a naturalized view of refugee reception in the context of the “refugee crisis” as a European challenge that Russia is not meant to deal with domestically.

In contrast to ideas of the West as Russophobic, several authors in Novaya gazeta see Russia as part of Western civilization. For example, in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks in France in November 2015, one Russian expert stated, “we are the people of Western civilization. Together with other European countries, Russia will defend its values – the republic, the enlightenment, the secular state – from all who encroach on them” (expert, op-ed, NG, November 16). Similarly, Grigorii Yavlinskii, a well-known liberal politician, predicted a future for Russia together with Europe:

It will become clear that Russia follows a common historical path with other European countries, including Orthodox countries, NATO members, together with the United States and all who share affiliation with European civilization in the broadest sense. (Political elite, op-ed, NG, October 19)

Representations of the EU/Europe, USA, and the West

In writing about refugees, commentators often refer to Russia’s relationship with EU/Europe, the USA and the West. Europe has been identified as Russia’s main “Other.” When Russians discuss Europe, they are also discussing themselves; thus, dominant ideas about Europe among political actors are crucial for the course of domestic and foreign policy (Neumann Reference Neumann2017, 3). The representations of the “refugee crisis” in my data represent a recontextualization of the discourse that has characterized Russian discussions of Europe for centuries: the question of whether Russia and Europe share the same path. In addition, ideas about the West may merge with ideas about the USA. Studies have noted that, in Russia, the West/USA is often represented as a distant enemy masterminding various plots against Russia, such as the Chechen terrorist threat (e.g., Wilhelmsen, Reference Wilhelmsen2014) and the 2014 Euromaidan in Ukraine (e.g., Gaufman, Reference Gaufman2017; Szostek, Reference Szostek2017; Moen-Larsen, 2020b). For many Russians, it has become natural to see the West as an opponent to Russia: this is a common myth about the West.

The three most frequently articulated representations in my data are of the West as the cause of the “refugee crisis” (47 texts), of the EU as disintegrating or being in crisis (26), and of disagreements about refugees in the EU (22 texts). Many texts claim that the West itself caused the 2015 “refugee crisis” and that the wave of refugees serves as “a punishment” to Europe (22 texts in Izvestiya, 3 in Novaya gazeta, and 22 in Rossiiskaya gazeta). Discursive moments such as “the West,” “the USA,” “Europe,” “NATO,” “the Middle East,” and “Africa” signal a geopolitical discourse. “The arrival of the barbarians is a punishment for your [the West’s] destruction of the Middle East, Asia and Africa for a whole millennium” (pundit, op-ed, Iz, September 8). According to Evgenii Shestakov, editor at the international politics desk at Rossiiskaya gazeta, “one of the key reasons for large-scale immigration from Libya was the military operation of the coalition headed by the USA, which led to the fall of the Gaddafi regime” (expert, op-ed, RG, June 18). The controversial Russian-Israeli journalist Israel Shamir presents the chronology of events thus:

NATO bombs Libya, the country falls to pieces, Gaddafi is lynched, and thousands of refugees leave the country – some go to the south of Africa, others over the sea. The colonies of refugees are growing in Europe, and the European social structure is falling apart under their weight. (Journalist, op-ed, Iz, April 22)

The above quote is representative of the texts that employ this line of argument. It is also the official Russian position, expressed by both President Putin (head of state, speech, RG, October 27) and his Chief of Staff Sergey Ivanov (political elite, interview, RG, October 20).Footnote 18 Some authors in Izvestiya and Rossiiskaya gazeta stress that the role played by Europe is minor in comparison to that of the USA: the USA is the main villain, with Europe as its weaker “little brother.” However, although the USA, as “the most influential force in the modern world,” is to blame for the conflicts that have led to the “refugee crisis,” Europe too bears responsibility, because it “did very little to stop the conflicts when that was still possible” (non-Russian political elite, op-ed, Iz, September 23). According to these commentators, US interference in conflicts in the Middle East brought about the rise of Islamic extremism, in turn forcing people to flee from their homes and become refugees (e.g., journalist, op-ed, Iz, November 16; political elite, op-ed, Iz, December 21; expert, op-ed, RG, November 17).

In addition to the geopolitical discourse, and discussions of the origins of the “refugee crisis”, the authors in my data also note the effects the crisis has had on the EU. Some writers, primarily in Rossiiskaya gazeta, claim that the “refugee crisis” poses a severe threat to the very existence of the EU. These commentators articulate a security discourse, combining the nodal point “the EU” with discursive moments such as “disintegrating,” “dying,” and “in great crisis” – all signaling the significance of the threat that the refugees pose to the EU (6 texts in Iz, 1 in NG, 19 in RG). For example, in a text titled “Migrants can ruin the EU,” the writer argues: “the illegals are becoming the main threat to the unity of the European Union” (expert, op-ed, RG, June 18). On a similar note, other commentators write, “The entire concept of the European Union is coming apart at the seams” (political elite, op-ed, Iz, December 21); “all illusions about a united Europe have collapsed” (non-Russian cultural elite, op-ed, Iz, May 6); “Europe is experiencing the most serious crisis in its history” (non-Russian expert, op-ed, Iz, November 9); and “the foundations of a united Europe have cracked” (political elite, op-ed, RG, October 23).Footnote 19

Other commentators paint a less dramatic picture: the European Union is perhaps not disintegrating, but the EU countries cannot agree on how to deal with the “refugee crisis” (4 texts in Iz, 3 in NG, 15 in RG). Key moments here are “disagreement” and “refugee quotas.” Several writers emphasize that the lines of disagreement about refugees go between countries in the West (except for the UK) and those in the East of Europe. For example, “Such a dramatic influx of refugees from the Middle East into Germany could seriously damage its policy. Eastern Europe does not share the Germans’ over-tolerance towards migrants and is closing its borders” (non-Russian expert, op-ed, Iz, September 25); “small states feel that their interests are not sufficiently taken into account, and refuse to obey common decisions” (non-Russian experts, op-ed, NG, December 18).Footnote 20

Contributions in the government-critical newspaper Novaya gazeta display a range of opinions. For example, several authors point out that the EU countries cannot agree on what to do with the refugees. However, there is less focus on refugees as the potential cause of Europe’s imminent collapse, or on representations of the West as the main cause of the Syria conflict, terrorist attacks, and the “refugee crisis,” although this discourse is articulated in Novaya gazeta. The opposite view is also represented: Europe can handle the refugees (non-Russian political elite, interview, NG, September 14). Those writing in Novaya gazeta focus less on rearticulating the myth of the USA as the main villain, with Europe as its weaker “little brother.” Several Novaya gazeta writers contest these myths and rearticulate the idea of Russia as part of Europe and the West.

Concluding Discussion

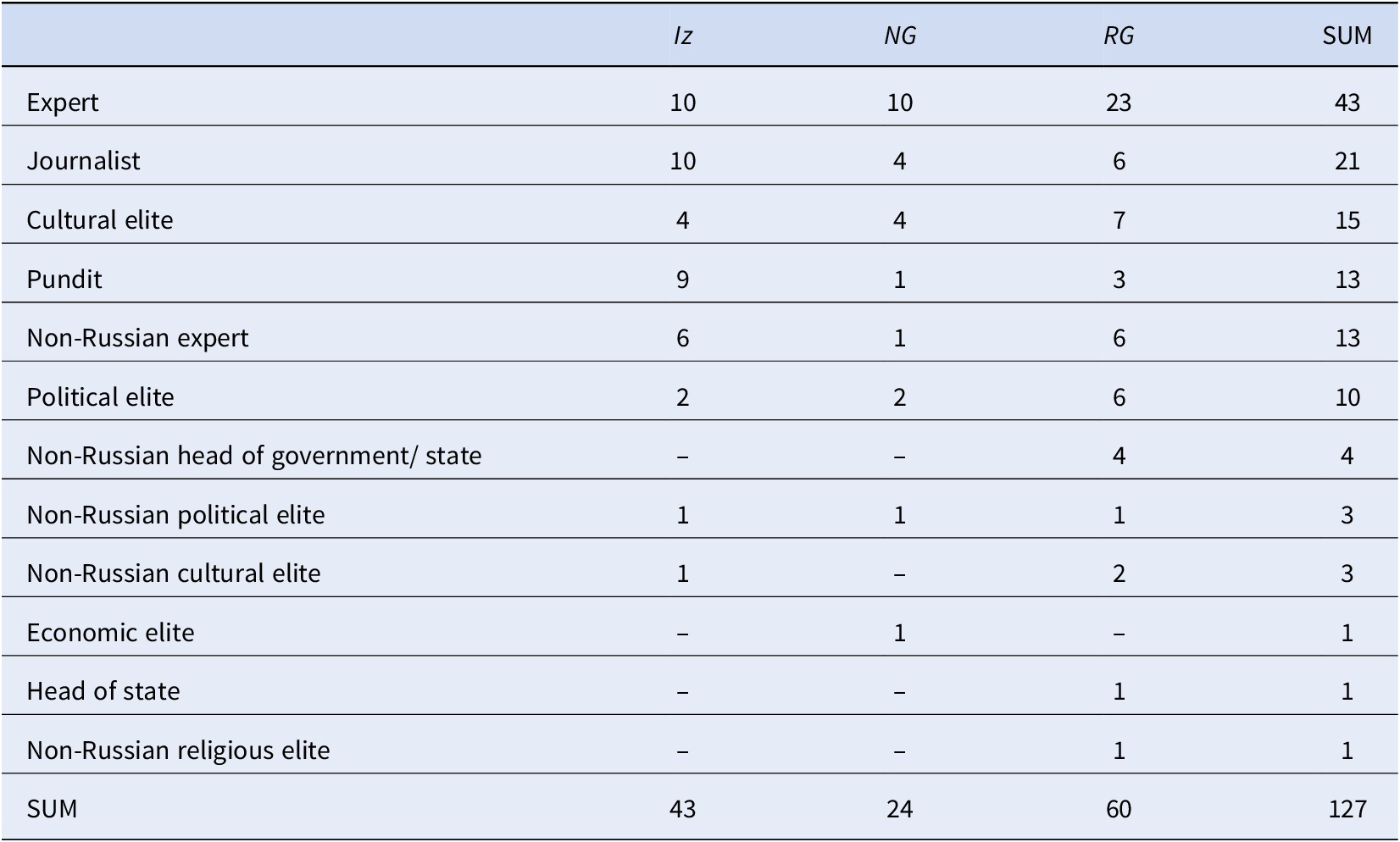

This analysis of opinion pieces and interview articles reveals three main discourses – the security discourse, humanitarian discourse, and geopolitical discourse – that have shaped the Russian media debate on the European “refugee crisis” (summarized in Table 2). Earlier studies of refugee representations in European media have found examples of the security discourse and humanitarian discourse, but the geopolitical discourse seems particular to the Russian media. This article has thus unpacked the representation of the refugee as a victim of interventionism and democratization processes promoted by the West in the Middle East and North Africa, an image not previously featuring in research on the 2015 European “refugee crisis.”

Table 2. Discourses, moments, and representations: main findings

The security discourse represents refugees as a threat to the EU, whether as a result of the sheer numbers arriving in Europe or because the refugees are seen as potential IS terrorists. Writers who articulate this discourse voice the myth of EU as weak, torn by internal conflict, disintegrating and, according to some, dying. Russia is presented as the hero who can save Europe, and the discourse legitimizes Russian military intervention in Syria as a contribution to the global fight on terrorism and neutralizing the IS threat.

In contrast, the humanitarian discourse views the refugees as victims of a violent conflict or war, now seeking asylum in the EU. From this perspective, it might seem reasonable to expect that Russia would consider contributing to solving the “refugee crisis” by granting asylum to refugees from Middle East and North Africa. However, given the near-complete absence of this discussion in my data, it is clear that the overwhelming majority consider Russia’s military intervention in Syria as its main contribution to resolving the “refugee crisis.” According to some authors, Russia’s motive for military intervention is to bring peace to the Middle East, so that people will have no reason to flee to the EU: instead, they will have incentives to return home.

Whereas the security and humanitarian discourses focus on the consequences of the “refugee crisis” for Europe, the geopolitical discourse focuses on the origins of the crisis. Authors here argue that the West, headed by the USA, has fueled revolutions and created conflicts that have forced the refugees to leave their homes. These refugees are the “punishment” for Europe’s meddling in the politics of other countries. Most of the contributions in the two pro-government newspapers rearticulate the myth of the West as Russia’s Russophobic “Other,” and with Russia as a great and strategic power now claiming its rightful place in the global order. Because the West has caused the “refugee crisis,” it must bear the responsibility for giving asylum to the refugees. By contrast, writers in the opposition-oriented Novaya gazeta articulate a rival geopolitical discourse, positioning Russia as part of Western civilization. They argue that instead of intervening in Syria, Russia should cooperate with Europe to find common solutions to the “refugee crisis.”

A discourse-theoretical framework has proven a useful tool for exploring the antagonisms and struggles over meaning in Russian newspapers. Threat representations of refugees are most common in pro-government newspapers, whereas images of refugees as victims appear in almost half of the texts in the government-critical Novaya gazeta. Importantly, none of those writing in Novaya gazeta portray the refugees as victims of Western interventionism and democratization. This clearly points to a clash between supporters of official discourse and the opposition as regards the meaning of “refugee.” Discourse-theoretical concepts have made it possible to tap into the core of these disagreements on how to interpret the 2015 “refugee crisis”: whether the refugees should be feared or helped, and why; who is to blame for the “crisis”; and how to solve it.

In addition, this article has shown how social actors recontextualize familiar discourses in interpreting a new phenomenon. The 2015 “refugee crisis” was in many ways unprecedented – at least, in recent history. When a new phenomenon arises, society needs a logical explanation and interpretation. If the phenomenon is framed as “a crisis,” then there is also a demand for a solution. In my data, Russian pro-government newspapers (re)articulate the decades-old myth about the antagonistic relationship between the West and Russia, presenting the West as responsible for the “crisis” and legitimizing Russian military intervention in Syria as a logical solution to the refugee problem. In contrast, several writers in Novaya gazeta are critical of Russia’s actions on the international arena and its geopolitical ambitions and view Russia as part of Western civilization. Thus, mythical representations of “Russia” become points of struggle between different discourses over the meaning of Russia’s identity.

Acknowledgements

I thank my supervisors Anne Krogstad and Helge Blakkisrud for their support, insightful comments, and suggestions. I also thank the two anonymous reviewers for helping me to improve this article.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2022.68.

Disclosures

None.