In the collections of the Society of Antiquaries of London are two large fragments of copper-alloy vessels accessioned under the numbers LDSAL88.1 and LDSAL88.2. Each of the surviving fragments comprises the complete rim circumference with triangular shaped lugs for handle attachment (although the handles are not extant) as well as the upper portion of the vessel body. The vessels have been in the collection of the Society since 1847, when they were recorded, without provenance, in the Albert Way catalogue.Footnote 1 As far as can be determined no other documentary evidence for these vessels exists, and Way made a clear distinction between vessels in the Antiquaries’ care with provenance and those without.Footnote 2 In the latter case parallels to other finds were provided and the two cauldrons were noted as having typological affinities with a similar vessel from an early medieval grave found in Sawston (Cambridgeshire).Footnote 3

More than a century and a half later, the perspicacious insight of Albert Way, FSA can be confirmed.Footnote 4 The two vessels are indeed similar to the cauldron from Sawston and can be classified as Westland cauldrons, probably of Hauken’s Type 2C.Footnote 5 This is a form of cauldron named after the Westland region of Norway where they were used as grave goods during the early medieval period. Such cauldrons are thickly distributed in Scandinavia, especially Norway but also with two concentrations in Eastern Sweden (Medelpad at the Bothnian Bay and Gotland in the Baltic Sea) and down into Denmark, the Low Countries and Germany, with a thinner distribution into France and Britain.Footnote 6 Associations with other objects in funerary contexts suggests that the Type 2C dates to ad 300–500.Footnote 7

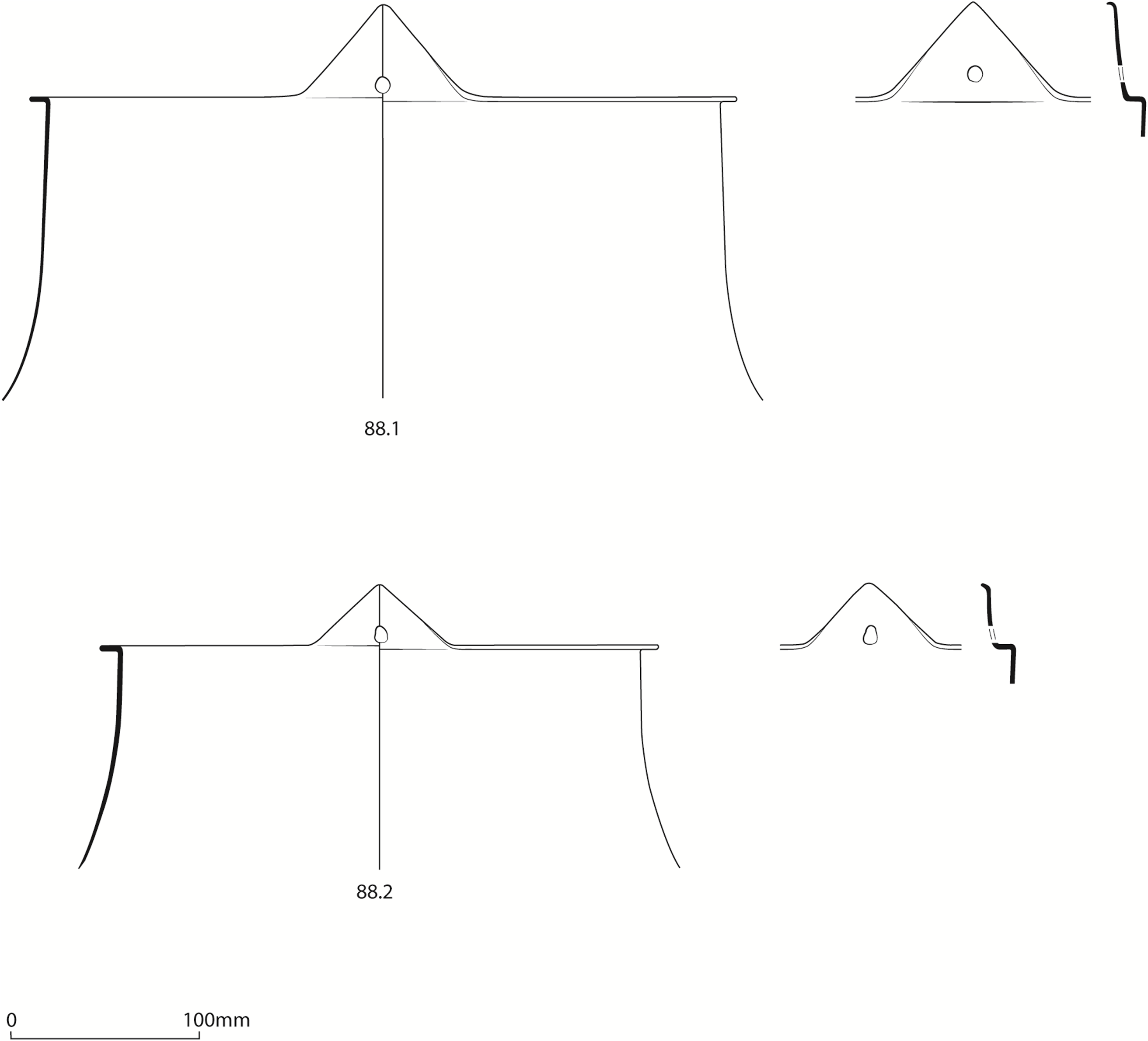

The two vessels are illustrated in fig 1 and a brief description of each follows:

-

SAL88.1 The larger of the two. The copper-alloy survives in a relatively robust state, although the lower part of the surviving fragment is quite fragile. The complete upper portion and circumference of the cauldron, with its two triangular lugs, survives. The tip of each lug has been bent to the perpendicular and the handle holes are circular. A little iron staining on the lugs and around the handle hole suggests that the handle may have been iron, and this is a feature of most early medieval finds.Footnote 8 Surviving weight: 1.519kg.

-

SAL88.2 The smaller of the two. As with 88.1, the copper-alloy fragment is well preserved, if a little fragile in its lower regions. The complete circumference survives, and the two triangular lugs also exhibit the perpendicular turning of the tips. On this vessel the handle hole is pear shaped, suggesting wear in use. A little iron staining suggests that the handle was of iron. Surviving weight: 0.721kg.

Fig 1. The two Westland cauldrons. Figure: author.

Given that these objects were first noted in 1847, we might reasonably ask where such vessels may have come from and how they may have passed into the possession of the Society. As with Sawston, there were a number of other antiquarian discoveries of Westland cauldrons and a kindred (perhaps later or insular) globular variant.Footnote 9 Excluding discoveries of the latter form, there are only two potential recorded discoveries that pre-date 1847: the single vessel from Sawston, and a group of three cauldrons from the Halkyn Mountain hoard (Flintshire).Footnote 10 The Sawston vessel has been illustrated and is missing one of its lugs, so cannot be either of the Society’s vessels.Footnote 11 Of the three Halkyn Mountain vessels, exhibited to the Society by Sir Joseph Banks, FSA on 22 May 1800, only one vessel is illustrated.Footnote 12 This is a much more complete cauldron than our examples, although lacking a handle and with pear-shaped holes through the lugs.

The short report on the Halkyn Mountain hoard published in Archaeologia in 1800 is the only record of this find. It is in fact the earliest recorded discovery and account of a late Roman or early medieval copper-alloy vessel hoard from Britain and is reproduced in full here:

The Rt Hon Sir Joseph Banks exhibited several ancient Culinary Vessels of Copper, supposed to be of Roman workmanship, represented in Plate xlix.

These vessels were found upwards of forty years ago, several yards below the earth, in sinking a mine shaft on Long Rake in the eastern part of Halker Mountain, Flintshire. They are all remarkably thin. [f ]

[f] There were two others of the same form as Figure 1, one of them 11½ inches [292mm] in diameter at the top and the other 14½ inches [368mm]. And two others similar to Figure 4, one of them 10¾ [273mm] inches and the other 4½ [114mm] inches in diameter. Footnote 13

The text in italics is reproduced in Archaeologia verbatim from the Society’s minute book and the footnote is clearly an addendum.Footnote 14 Figure 1 referred to the illustrated Westland cauldron and thus the footnote points to two other vessels of this type that were exhibited by Sir Joseph to the Society. Is it too much to suggest that these vessels are one and the same with LDSL88.1 and LDSL88.2? It is difficult to know where else the Society could have acquired two Westland cauldrons prior to 1847. The early nineteenth century was also a difficult time for the Society, and under such circumstances objects could be mislaid or lose their provenance.Footnote 15 There is also one other piece of evidence that may further support the suggestion that the Society’s cauldrons are the last remnants of the Halkyn Mountain hoard.

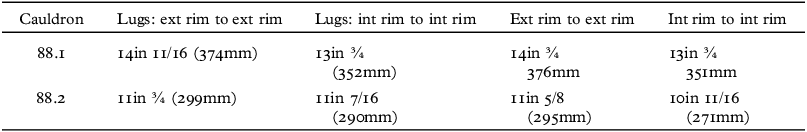

The diameters of the two cauldrons were provided: 11.5in and 14.5in. Way’s measurements of the same vessels gave 11in and 14in.Footnote 16 Neither of the two cauldrons is today completely circular, they are slightly misshapen. Nevertheless, the opportunity was taken to measure the diameters of each vessel. This included measurements between the lugs from the exterior of the rim to exterior and the interior of the rim to interior. The same measurements were taken perpendicularly to the axis of the lugs, giving two diameters quartering the circle of each vessel’s mouth. The measurements were taken using a cloth measuring tape with metric and imperial gradations and are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Imperial and metric measurements of the cauldron diameters.

These measurements are not conclusive, but we should probably not expect them to be. We do not know the precise location was measured on each vessel in 1800, nor do we know how they were measured or with what care. What is striking from this analysis is that when measured from rim exterior to rim exterior the larger of the vessels is something in excess of 14.5 inches in diameter and the smaller has a diameter something in excess of 11.5 inches. Indeed, the diameters across the vessels (rather than between the lugs) measure 14.75in and 11.625in. Both of these are close enough to 14.5in and 11.5in to be suggestive. This evidence becomes more compelling when it is recognised that all of the other Westland cauldrons from Britain, with the exception of a twentieth-century find from Grassington (North Yorkshire), have diameters narrower than 11in.Footnote 17 In the small British sample, the Halkyn Mountain and the Society’s cauldrons stand out as being particularly wide mouthed.

I propose that LDSAL88.1 and LDSAL88.2 are the two additional Halkyn Mountain Westland cauldrons described in the footnote to the report in Archaeologia. Occam’s Razor suggests that the Halkyn Mountain hoard is the most likely origin for two cauldrons entering the Society’s collections during the early nineteenth century. The measurements of the diameters are supporting evidence for this hypothesis. If this interpretation is accepted, then we have in the collections two fascinating objects that are a testament to not only the first late Roman or early medieval copper-alloy vessel hoard recorded in Britain, but also to the Society’s mission.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It is with gratitude that I dedicate this note to the late Prof Dai Morgan Evans, FSA, who suggested to me the possibility of a link to the Halkyn Mountain hoard. I would also like to record my thanks to Kate Bagnall, the collections manager at Burlington House. Her assistance and positivity about the project are much appreciated. Faith Vardy kindly drew the vessels with great efficiency and professionalism.