We have known each other for decades. I (Gabe) slept on Ray’s couch when I came for a graduate student recruitment visit to Ohio State. At the time, Ray was studying for comps, and we hit it off immediately. Beyond the fact that we are both “Bunchees”—alumni of the prestigious Ralph Bunche Summer Institute (Sanchez is part of the 2000 class that was the first to be hosted by Duke University, while Block attended the RBSI back in 1998, when it was still at the University of Virgina)—we bonded over common interests, outlooks, and stories about growing up. Gabe eventually went to the University of Arizona, but an enduring friendship was born. We are so close that Ray was groomsman at Gabe’s wedding, and we refer to each other as brothers.

Since attending the RBSI, we have each excelled in our professional journeys. Sanchez is professor of political science, the director of the UNM Center for Social Policy, and a founding member of the UNM Native American Budget and Policy Institute at the University of New Mexico. Block is the Brown-McCourtney Career Development Professor in the McCourtney Institute and an associate professor in Penn State’s Departments of Political Science and African American Studies.

Beyond our faculty affiliations, we are community-engaged pollsters who study the intersection between race and ethnicity, media messages, and political mobilization. We often work together, Gabe in his capacity as Vice President of Research at BSP Research, and Ray as a Senior Research Advisor for the African American Research Collaborative.

Our current joint project on vaccine uptake reflects the tightness of the Sanchez-Block bond and is the culmination of our efforts to apply our research and methodological training to the topic of health inequalities. With resources and support from the Commonwealth Fund, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the WK Kellogg Foundation (and in consultation with a team of experts who can speak from different perspectives about the importance of boosting vaccine confidence), we conducted a large survey of US adults. The 2021 American COVID-19 Vaccine Poll was in the field from May 7 to June 7, 2021. A sample size of 12,288 (which includes nationally representative and sizable sub-samples of African Americans, Latinos, members of the AAPI community, American Indians, and white respondents) makes it the largest and most comprehensive poll of its type.

The goal of this survey is to gauge what Americans from a broad range of backgrounds believe about the vaccine, whether they plan to take it and when, what messages would increase their likelihood of taking the vaccine, and what messengers they trust on vaccine uptake. In addition to its comprehensive and diverse sample, the survey is unique because we ask an array of questions gauging whether respondents have taken or are willing to receive a vaccine. The specific question wording is: How about the COVID-19 vaccine, have you: received both first and second dose of a two dose COVID-19 vaccine; received only first dose of two dose COVID-19 vaccine; I have received one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine that only requires one dose; I have NOT had any COVID-19 vaccine. Then, we customize the experience of the survey so that, beyond the "common content," respondents get different sets of follow-up questions based on how vaccine-hesitant/willing they say they are. Technical details are available at CovidVaccinePoll.com, a user-friendly interactive website.

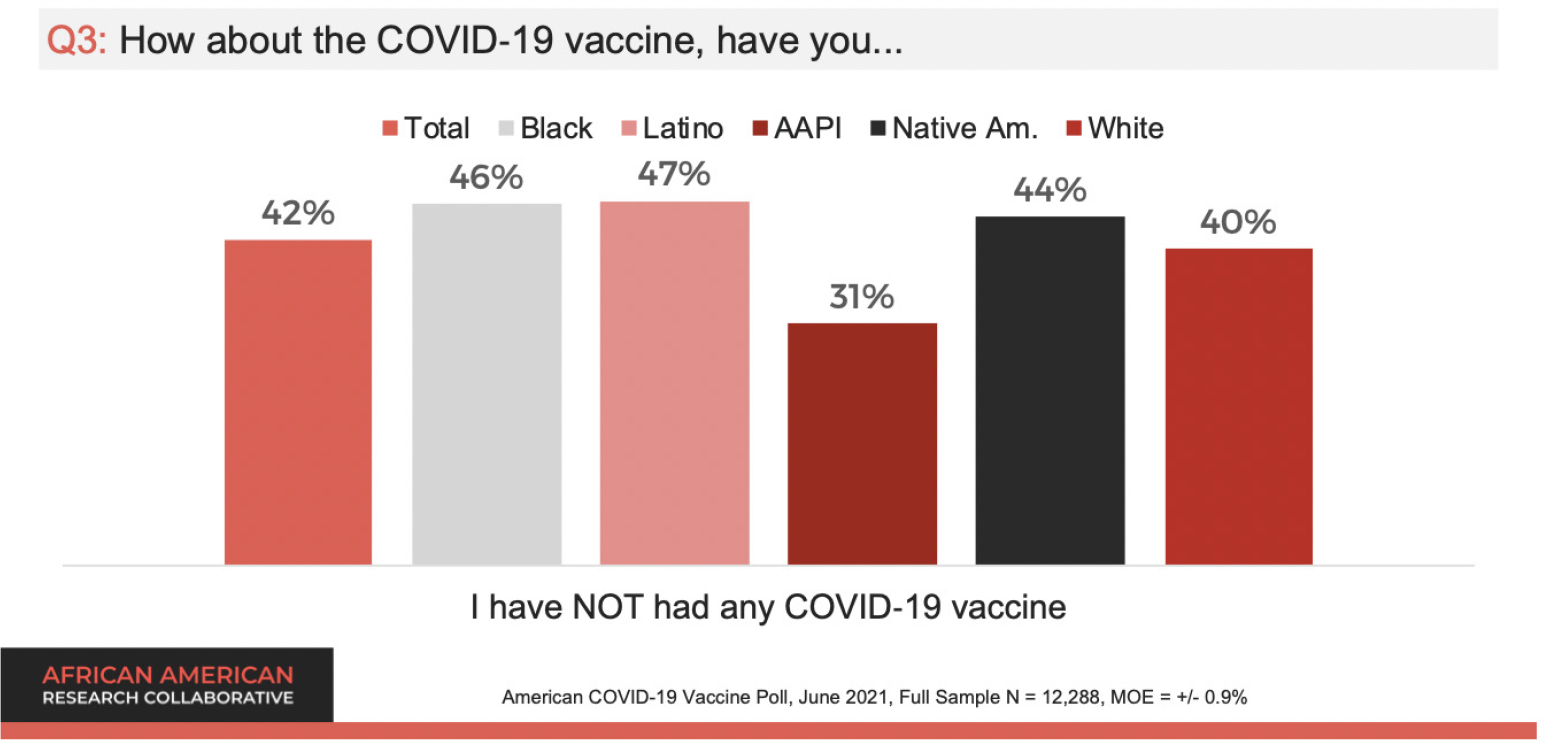

The survey results provide novel discoveries while also confirming preexisting suspicions. For example, our findings comport with recent narratives about the vaccine rollout and implementation rates. Although vaccination rates fluctuate when sorted by race and ethnicity (See figure 1), it is critical to note that just over 40% of our total respondents report that they have not received any of the available COVID-19 vaccines. This suggests that vaccination uptake will need to improve among ALL racial and ethnic groups in order for the nation to reach the goal of herd immunity. Asian American and Pacific Islanders are the least vaccine hesitant, and African Americans and Latino/as report some of the highest vaccine-hesitancy rates. This is further evidence of how difficult it would have been to meet President Biden’s ambitious goal of vaccinating 70% of all US adults by July 4, 2021.

Figure 1 Survey Respondents Who Are Not Vaccinated

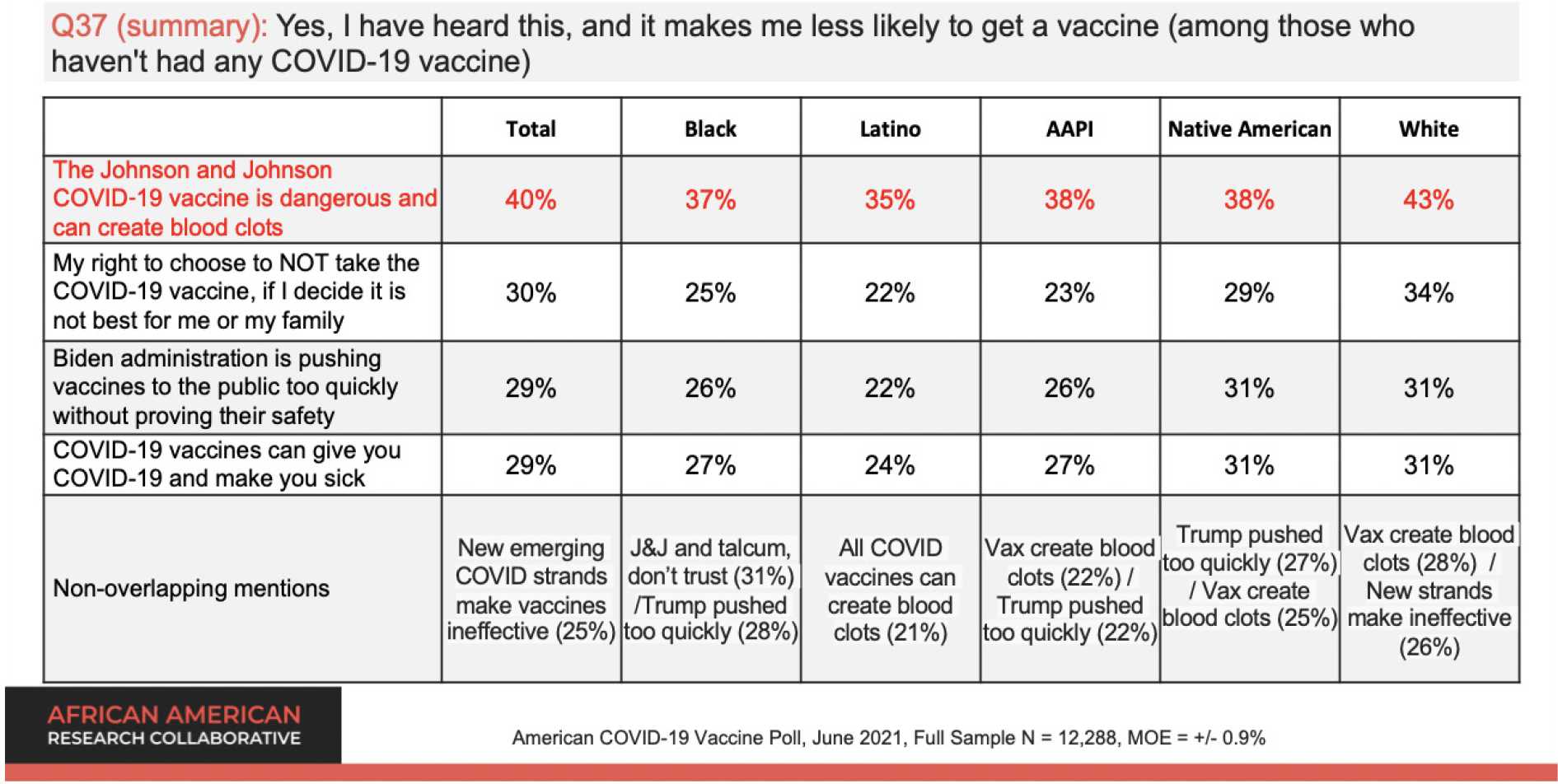

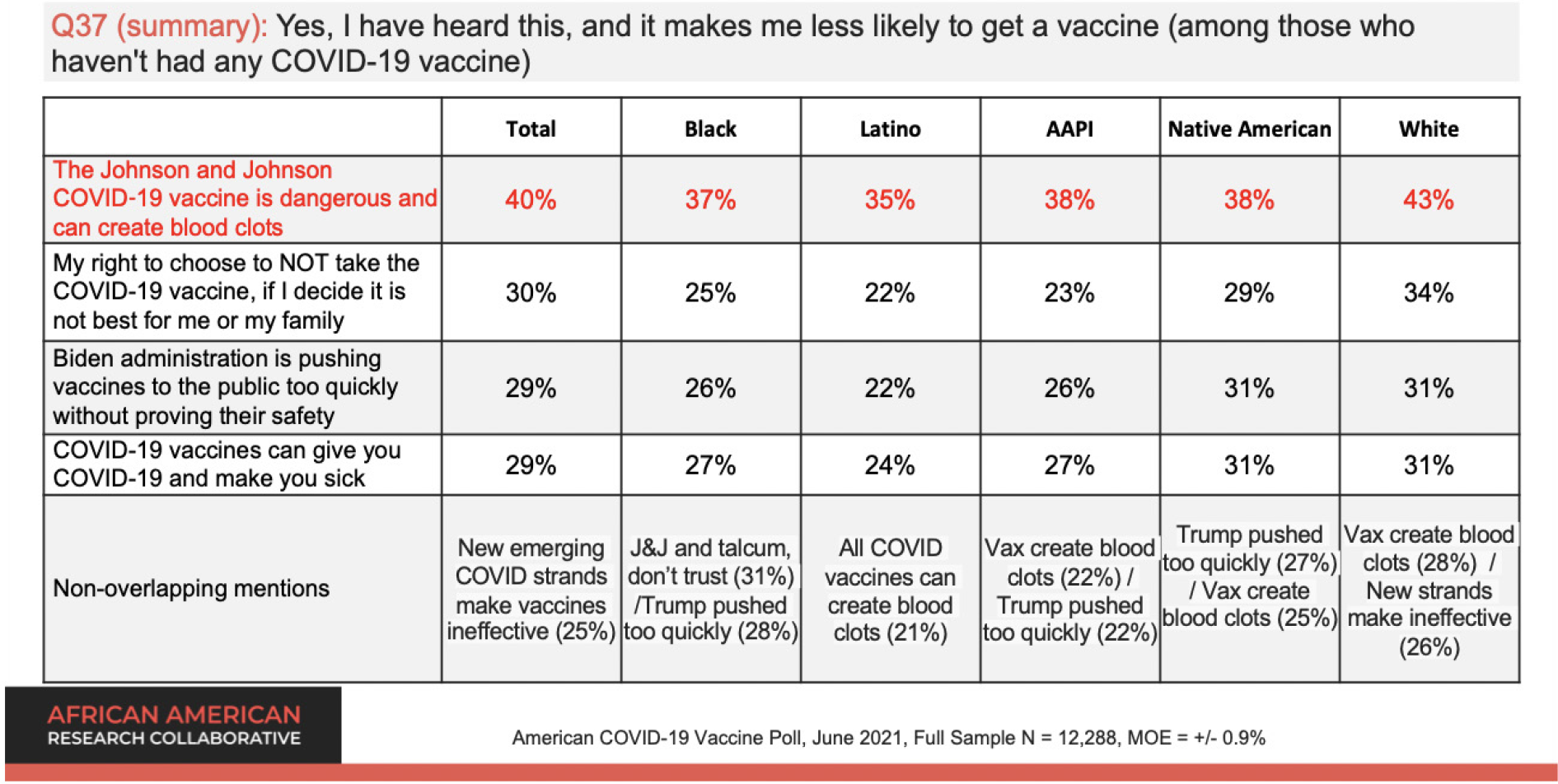

We also included survey items representing various reasons for not receiving a vaccine. Specifically, we wanted to know whether unvaccinated respondents had heard of such reasons before, and, more importantly, whether these reasons had any effect on their willingness to get vaccinated. Figure 2 below shows that the top reasons for hesitancy concerned the perceived danger of vaccines in general—and Johnson & Johnson in particular (this worry that resonated with African Americans especially, given ongoing lawsuits regarding the connections between the use of the company’s talcum powder and ovarian cancer). Unvaccinated respondents are also suspicious about the speed with which the vaccines were being pushed out, and Black and American Indian respondents expressed similar concerns about the Trump administration’s fast-moving rollout efforts. Several additional reasons for vaccine hesitancy were “non-overlapping” in the sense that some groups of respondents mentioned them while other groups didn’t. For example, among African Americans and Native Americans/American Indians, concerns over the speed with which the Trump administration pushed the vaccine were particularly relevant, while the perceived danger of vaccines creating blood clots ranked highly among respondents who self-identify as Latino/a, Asian American or Pacific Islander, or white.

Figure 2 Top Reasons for Hesitancy Among Non Vaccinated

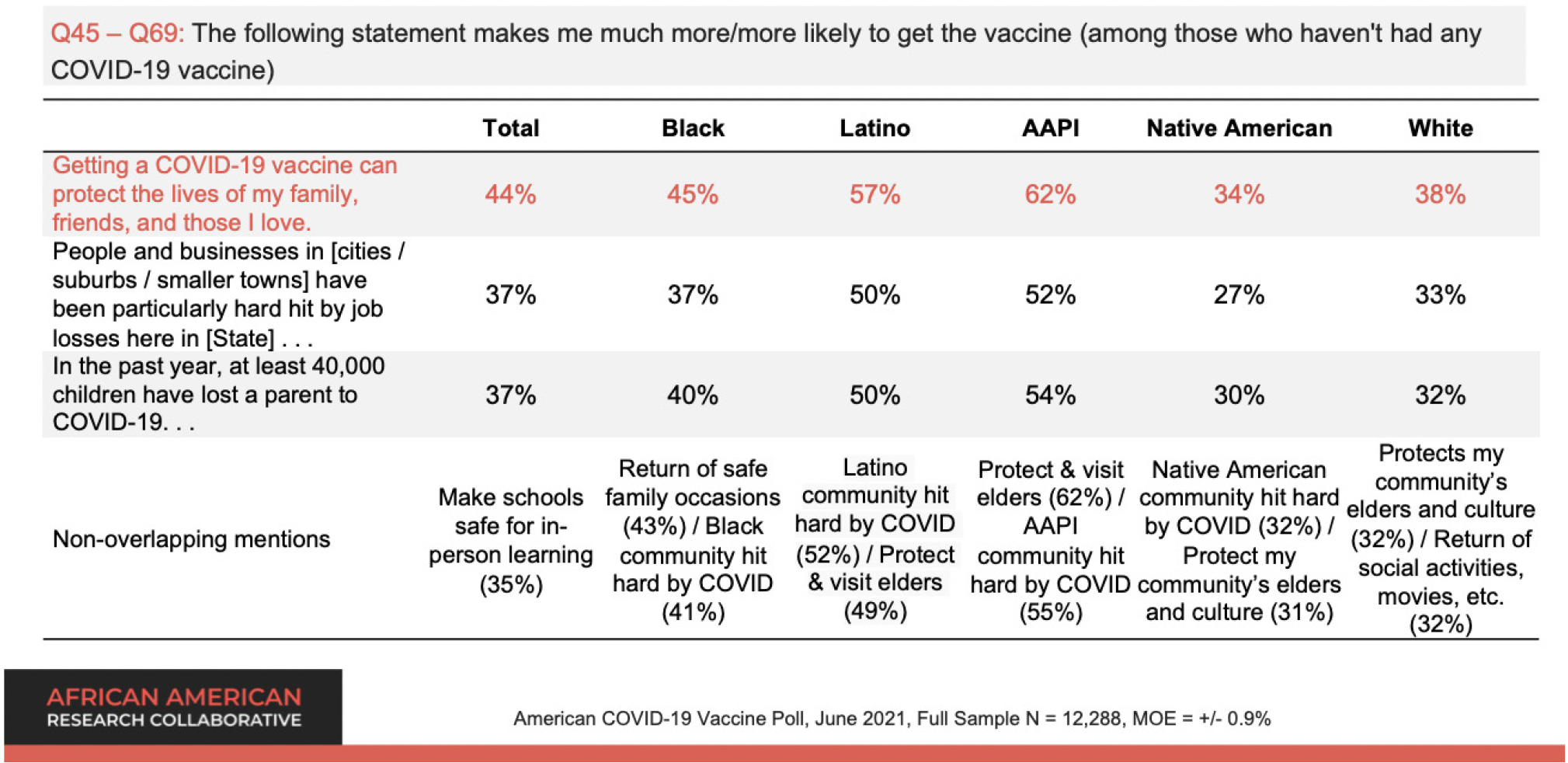

In addition to exploring why people are hesitant, we included some items in our survey that gauge the usefulness of certain messages for boosting vaccine uptake. What messages motivate people? We find that protecting the lives of family and loved ones resonates as a powerful motivator, as is the idea of getting vaccinated to support for local businesses. Notice that these messages are generally about citizens helping the people they know and love (loves ones, local businesses, etc.) and honoring those who have lost their lives to COVID-19. See figure 3.

Figure 3 Top Pro-Vaccine-Uptake Messages

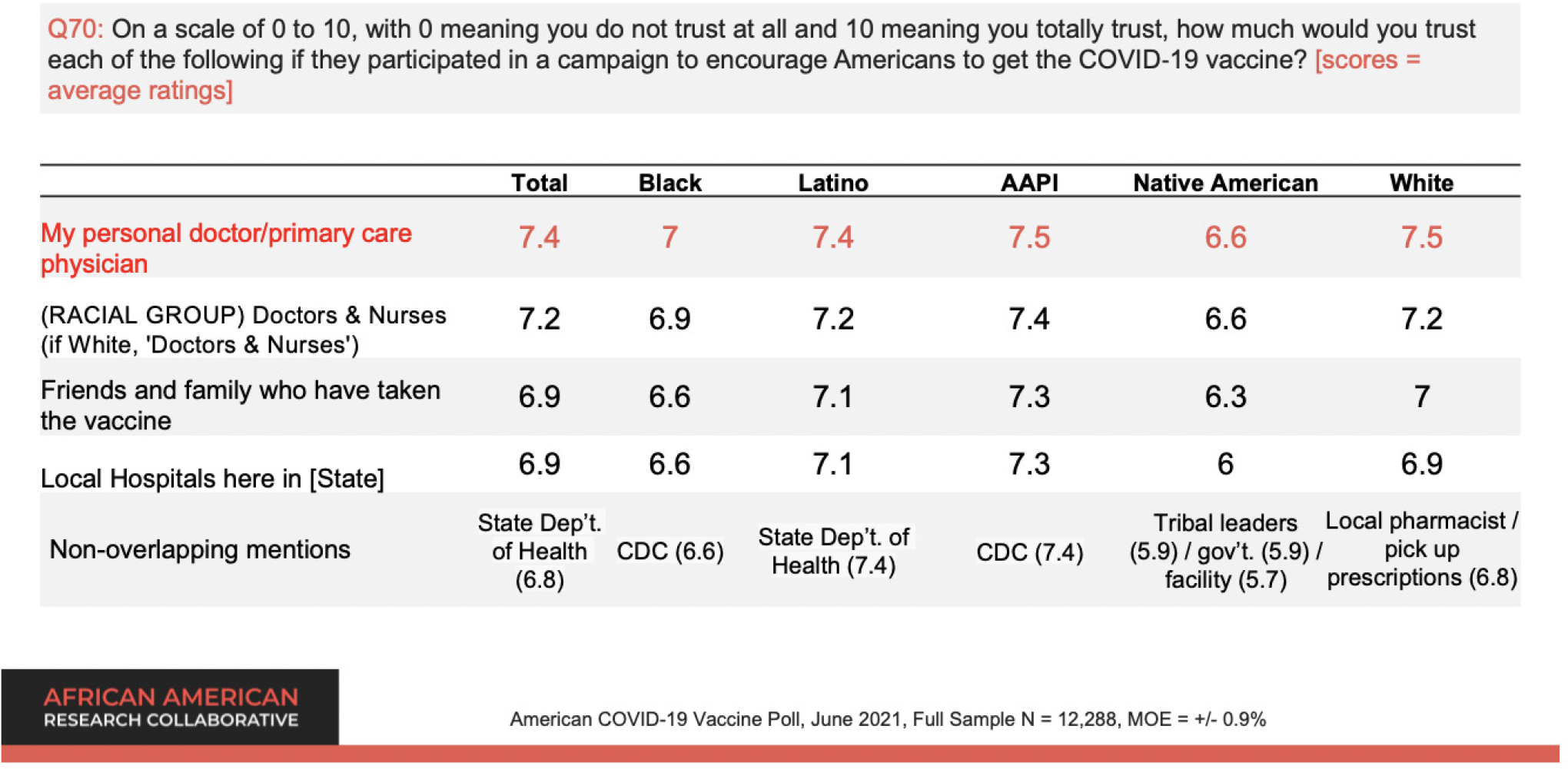

But it is not enough simply to acknowledge that certain vaccine-uptake messages work better than other. One must also consider the person or people delivering those messages. We therefore asked respondents to rate (on a 10-point scale) who they believed were the top pro-vaccine-uptake messengers. It was clear that people generally trust doctors and primary care physicians to offer advice about vaccines—and, most importantly, respondents are open to listening to doctors and physicians when they encourage vaccines (figure 4 below).

Figure 4 Top Pro-Vaccine-Uptake Messengers

Both the health and the wealth of our planet depends on the successful containment of the spread of the coronavirus. As we near our second year of this difficult reality, we acknowledge the innumerable losses and hardships borne of the pandemic, and we seek to fight against the suffering that we have collectively been thrust unfairly into. In this sense, this research project represents not only a welcomed collaboration, but also a form of activism: learning more about how why some accept the vaccine while others reject it, and by exploring potential ways to reach out to—and potentially persuade—vaccine-hesitant citizens to roll up their sleeves and receive their shot(s). ■