1. Introduction

One of the big questions in the social sciences is why societies display such large differences in economic and social performance, and which distinguishing features and characteristics at the societal level underlie these differences. In search of answers, many scholars have focussed on the institutional characteristics of societies, either being forms of political organization, social structures or the rules that govern economic life. A large strand of works has looked, for instance, at the organization of exchange and allocation of goods and production factors, dominated either by kinship structures, communities, feudal systems, markets or states, whilst others have primarily focussed on differences in the institutions that shape political life. To understand how such institutional characteristics affect economic and social outcomes, we need to clarify how they determine the incentives of the actors involved at the micro level. These incentives can be found, for instance, in the desire to generate or extract rents, find safety, better employ labour or land, or acquire freedom or political leverage. In addition, we should ask how the institutional structure of society is itself shaped by these incentives and how and why it develops over time, for instance, from less to more open systems of exchange or political interaction.

An important, recent contribution to this field is Violence and Social Orders, by North et al. (Reference North, Wallis and Weingast2009, henceforth NWW). They stress violence as the crucial variable in understanding differences across societies. Specifically, they focus on the need of societies to control large-scale, organized violence and on their relative success in doing so. Violence may lead to destruction of lives and capital goods, and deter interaction, exchange, trade and the benefits of specialization that come with trade, leading to significant welfare losses (Acemoglu and Johnson, Reference Acemoglu and Johnson2005). This idea is the starting point of NWW in explaining and understanding the existence of specific social orders, which can be interpreted as archetypical societies, with specific institutions that emerge because of the necessity to control violence. They distinguish three social orders: the ‘foraging order’ that governed human life until the Neolithic Revolution, approximately 10,000 years ago; the ‘limited access order’ that was prevalent since then; and the ‘open access order’, which developed only some 200 years ago, in a handful of western countries.

The book by NWW is ambitious – as illustrated by its sub-title A conceptual framework to understand recorded human history – and it is widely acknowledged to be an important contribution. Its impact on actual research up to now, however, remains limited. Possible causes are that the book is conceptual and highly abstract, and that the economic logic behind some of the mechanisms of the social orders, and of transitions between orders is unclear. The authors have decided not to develop a formal model or empirically testable hypotheses (p. xii). Instead, they provide a conceptual framework wherein violence is linked to political organization and economic performance, and, importantly, to the distribution thereof. However, the incentives of actors are mentioned but left implicit in their framework. In part, this is because they do not discuss the interaction between production and appropriation in a systematic way. As a consequence of not specifying incentives, it is difficult to comprehend what the problems, constraints and strategies of the agents are, as several reviewers have already remarked (e.g. Bates, Reference Bates2010: 755). NWW thus present to the social sciences an encompassing but abstract framework to distinguish between different societies through time and space, and understand the basic functioning of each of these societies. In this paper, we argue that the conceptual framework of social orders can be advanced precisely by specifying explicit relations between appropriation – based on the distribution of violence capacities – and production, following van Besouw et al. (Reference van Besouw, Ansink and van Bavel2016). Then, using these relations, we further assess the interaction between violence, political organization and economic performance. Also, we further specify the role of organizations in this interaction; a role that is stressed by NWW (see below), but will be specified here by explicitly relating it to incentives and production. Doing so for the ‘limited access order’, we not only sharpen our understanding of the mechanisms of social orders, but also come closer to understanding societal development and major transitions of the type discussed by NWW – both political and economic – and to position them in time more accurately.

Before we present our additions in detail, it is necessary to discuss how NWW conceptualize the limited access order – alternatively called the natural state. A limited access order ‘manages the problem of violence by forming a dominant coalition that limits access to valuable resources – land, labour and capital – or access to and control of valuable activities – such as trade, worship and education – to elite groups’ (NWW: 30). Membership of this coalition is, by construction, limited to individuals with the capacity to muster organized violence. In the terminology of NWW, they are ‘violence specialists’. Violence specialists form a subset of a society's population and are able to use large-scale, organized violence and to coerce others under the threat of violence. Their ability to do so is enhanced by patronage networks, social capital, human capital, physical strength, wealth, status or prestige, and these to varying degrees, depending on the specific context. The rest of the population, in contrast, has no capacity for large-scale, organized violence and is therefore in principle not able to join the elite. Violence specialists within the elite coalition use their power to collectively extract rents from the rest of the population; rents that are used to hold the coalition together. Although the coalition utilizes its coercive power against the rest of society, under the threat of violence, it restricts open violence. The result is a social order with a strong elite that exercises its coercive power to extract rents from the rest of society. Although competition amongst violence specialists for the distribution of rents may exist, membership of the elite coalition entails a lasting, informal agreement to respect the privileges and rents of other members. On the other hand, the elite coalition competes, as a group, with violence specialists outside their coalition. Violence specialists outside the coalition – termed ‘warlords’ here – are those who refuse to commit to the coalition's agreements and those who are not allowed access to the coalition. As violence specialists, they have the capacity to extract rents from the ordinary population. They thus compete for control of the society's rents. In open access societies, by contrast, the states possess a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence, as they have consolidated military and police organizations which are controlled by the political system. All citizens have access to the political and economic systems, and they have the right to form organizations. These sustain impersonal exchange and allow all citizens to compete for political control and for economic rents, which are continuously eroded as a result of this political and economic competition (NWW: 21–23). By this definition of social orders, we follow NWW in arguing that almost all historical societies and most contemporary ones can be characterized as limited access orders.

We should note a marked difference between the ‘elite coalition’ in limited access orders as depicted by NWW, and of ‘the elite’ as set out in the literature that compares conflict and development in anarchy with some form of hierarchy (e.g. Acemoglu and Robinson, Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006; Bates et al., Reference Bates, Greif and Singh2002; Grossman, Reference Grossman2002). In the latter, the elite is generally treated as a monolithic entity maintaining order amongst the rest of the population and levying taxes in return. In the limited access order, however, the elite coalition emerges from the pool of violence specialists, and cooperation of violence specialists in this coalition is not self-evident as there is always a threat of their not joining or of their leaving the coalition – the latter, in our view, is nothing more than a violence specialist choosing to no longer obey the coalition's agreements. Hence, the elite is a composite entity, and behaviour of individual violence specialists is constrained by their relations with other violence specialists. This interpretation of the elite coalition strikes us as a major advance and brings reasoning closer to real-world situations, both historically and at present. One can, for instance, think of the situation in Western Europe in the Middle Ages. Here, the elite would be the feudal elite, with its members competing with each other for rents. Warlords, too, would be violence specialists, but operate outside the dominant feudal order as robber barons, captains of roving mercenary troops or noblemen with independent domains or territories. In the present-day world, in limited access orders like Burma, Cuba, Mexico, Russia and many sub-Saharan countries, the elite would be the politicians and officials in power, who use the state apparatus as a personal fiefdom and compete with each other for rents, whilst the warlords would be rival factions and rebel leaders (see case studies in North et al., Reference North, Wallis, Webb, Weingast, North, Wallis, Webb and Weingast2013).

Whilst NWW take it as given that violence specialists prefer to be part of the elite coalition, here we will endogenize this preference by introducing production as an important variable. Depending on production levels and the size of the elite coalition, violence specialists may prefer not to enter the coalition, but to operate alone as warlords. The advantage of not entering is that warlords are not bound by any rules of the coalition regarding the use of violence and the rate of appropriation of production, and may therefore be able to generate a higher income than if they had joined the elite coalition. This implies that maintaining a stable elite coalition within limited access order is even more problematic than NWW already assume. Clarifying the incentives of violence specialists allows us to identify this trade-off and forms an important addition of this paper. In section 2, we will explain such incentives in detail.

A second major advance made by NWW is the way they highlight the role of organizations. In Violence and Social Orders, organizations form a major element in the transition from limited access to open access orders. As such, they are analytically separated from institutions, a distinction sometimes considered as one of North's main contributions to the literature (Wallis, Reference Wallis2015). In his earlier work, North had treated organizations as manifestations of institutions, which already was an advance over the neoclassical focus on individuals. By defining institutions as the rules of the game and means of enforcement, and then separating the rules from the organizations that actually play the game, it became possible to have a dynamic relationship between the interests and incentives facing the organizations and the structure of the rules.

This separation, and the resulting role of organizations, is particularly evident in Violence and Social Orders. The limited access orders are divided there into three ideal types: fragile, basic and mature orders, each typified by the role and structure of their organizations. These ideal types together form a spectrum along which organizations become more durable, more complex, less bound to personal power, more numerous and less dependent on the dominant coalition (NWW: 20–21 and 41–49; North et al., Reference North, Wallis, Webb, Weingast, North, Wallis, Webb and Weingast2013: 10–14). Even though there is no teleological progress, since mature limited access orders can regress and revert again, the organizations thus form a vital component in development, as they do also in the transition from mature forms of limited access orders to open access orders. In the latter, the number of organizations is large, they can be freely founded by all citizens, and access to them is an impersonal right of all citizens. An elaborate system of rules, and checks and balances on powerful individuals and on impersonalized organizations sustain the open access order. The number of open access orders, by their definition, so far remains small.

Our paper is inspired by NWW's Violence and Social Orders, but we claim to make three advances, by further scrutinizing and adjusting important parts of it. First, we stress the trade-off violence specialist's face in deciding to join the elite coalition as a crucial force of inertia in the political and economic development of limited access orders. Second, we discuss the role and importance of organizations within this framework. That is, we discuss the importance of organizations in developing more stable configurations of violence specialists, and the effect of organization on production – as a stylized representation of economic development. We do this for what has been in most parts of history, and in most parts of the world still is, the most widespread order: the limited access order. To this end, in section 2, we use a formal model, based on van Besouw et al. (Reference van Besouw, Ansink and van Bavel2016) that includes production as a variable, in order to gain insight into the incentives of the violence specialists. Next, we follow North in his stress on the role of organizations and assess their role in relation to incentives and production. As a first step, in section 3, we discuss what these organizations actually are, using the historical record. This discussion will establish the need to go beyond the single category of organizations considered by NWW. Whilst the organizations discussed by NWW are top-down, and dependent on the state, we suggest including a category of bottom-up organizations. In section 4, we will use the model to stress the importance of distinguishing between these two types of organization. In section 5, we will return to the historical record and discuss what these results imply for the chronology of developments as pictured by NWW. Our third, and final contribution is that our analysis leads us to suggest that this chronology needs to be revised and that relevant developments started earlier in time than NWW argue. Section 6 summarizes our main findings.

2. Clarifying economic incentives: a model of the limited access order

In order to gain more insight into the incentives of actors, we represent the limited access order by means of a model, based on van Besouw et al. (Reference van Besouw, Ansink and van Bavel2016), and we refer to the Appendix of the current paper for technical details of the model. Here, we single out the elements of the limited access order that are central to our discussion, and we focus on how these elements interact with each other through the behaviour of violence specialists and their interaction with the rest of society. Accordingly, we make three simplifications. First, we model a society in isolation. This means that, abstracting from reality, no exchange or interaction with other societies exists. Doing so, we follow NWW, who also largely leave this interaction outside of their analysis. This omission is noted in various papers discussing how developments within a limited access order can be influenced by its interactions with other societies (Frankema and Masé, Reference Frankema and Masé2014; Grimmer-Solem, Reference Grimmer-Solem2015). Abstracting from this interaction, however, allows us to focus on the central elements here: the internal consistency of a limited access order, the incentives of violence specialists and production.

Second, we model the interaction between the distribution of violence specialists and the level of production in a static model. Thus, we do not account for potential long-term effects of particular distributions of violence specialists on the production process in the model. Such effects are, of course, possible when the relative size of the elite coalition has effects on factors such as population size – relative to the number of violence specialists – technological progress or institutional arrangements. Although these long-term effects are plausible, we would stress that the inherent instability of the coalition and the strong tendency of violence specialists towards warlordism – as will be demonstrated below – limits the scope for structural change in the economy of limited access orders. Instead, we follow NWW in suggesting that organizations are the vital ingredients for fostering long-term developments – and discuss these from section three onwards.

Our third simplification is that we consider violence specialists as individuals and, for reasons of practicality, their capacities as homogeneous. The latter has two technical implications. First, it allows us to ignore the specificities of the formation and size of patronage networks of each individual violence specialist. Second, we need not explicitly model entry into and exit from the elite coalition because violence specialists are identical and face identical choices. Of course, heterogeneity across violence specialists, and the balance of power within and composition of elite coalitions are important elements of a limited access order but we argue that this is not crucial for understanding the main interactions between violence specialists and producers in a limited access order but rather adds to explaining empirical variation across countries.

The central element in our model is the violence specialists’ behaviour in terms of their choice between joining the elite or becoming warlord, and its implications for the rest of society, notably its interaction with production levels and welfare. The choice between coalition membership and warlordism depends on the relative profitability of joining the elite – and, accordingly, to remain an elite. In other words, is it profitable enough for violence specialists to join the elite and thereby settle to abstain from violence, at least vis-à-vis other coalition members? The mechanism that we employ to model this choice is that specialists will choose the most profitable ‘occupation’. As a result, violence specialists continue changing their occupation until the payoffs of both groups are equalized.

Adding to NWW, we proceed by formulating the payoff structure and resulting incentives for two different types of agents – see van Besouw et al. (Reference van Besouw, Ansink and van Bavel2016) for a full discussion, and the Appendix to this paper for technical formulations. The payoff to violence specialists, the first type of agent, is determined by the total size of production, the relative share of production they can access and the rate at which they appropriate production from this accessible share of production. We assert that the appropriation rate of warlords and elite members differs crucially. Coalition members, by virtue of their commitment to respect the coalition, have relatively secure access to some share of total production. This allows these individuals to expect future benefits of their choices. Accordingly, they can decide to limit their rate of appropriation when this would increase production. Warlords do not have a secure access to a share of production and, therefore, appropriate as much as they can. This implies that warlords have a clear advantage in terms of their appropriation rate. Members of the elite coalition have a relative advantage in fighting warlords by virtue of their cooperation. We refer to this advantage as the ‘cooperative quality’ of the elite – see section 3 for a discussion. The second type is a representative producer. The producer optimizes consumption, which is total production net of production costs and appropriation. Production requires costly investments governed by decreasing returns, which induces the producer to reduce his production in response to appropriation.

Violence specialists and the representative producer interact with each other in three subsequent stages of our model. In stage 1, violence specialists choose their occupation, which yields a specific distribution of elites and warlords. Each group controls a share of society and its production, determined by the relative size of both occupational groups and the cooperative quality of the elite – this is formalized in what we call a control function.

In stage 2, given the outcome of the control function, elite members decide on their level of appropriation – termed ‘tax rate’ in what follows – whilst taking into account that a high tax rate may deter production such that reducing the tax rate might increase the elites’ payoff – as in McGuire and Olson (Reference McGuire and Olson1996). By construction, warlords exploit their violence capacities in order to appropriate all production that is under their control. In the model, we find that this optimal tax rate depends negatively, and only, on the marginal product of investments in production.

In stage 3, given the outcome of the control function and the elite tax rate, the representative producer chooses his production level. The level of production is governed by a conventional production function.

We assume that each agent – i.e. elites, warlords and the representative producer – maximizes his payoff (see Appendix). For the representative producer, this is simply production net of production costs (in terms of productive investments) and net of appropriation by warlords and the coalition. For elites, this is the tax income. For warlords, this is the, deterministic, appropriation income. This results in a static model in which all agents make optimal decisions, taking into account the decisions made by the other agents (see van Besouw et al., Reference van Besouw, Ansink and van Bavel2016 for a detailed analysis of this model).

To analyse this model, we need to specify both the control function and the production function. We choose to adopt very intuitive properties for both functions. For the control function, we assume that the share controlled by the elite increases (decreases) in the size of the elite coalition (the number of warlords) – with diminishing returns to elite size – as well as in the elite's cooperative quality, i.e. the extent to which the coalition cooperates and thereby has a strategic advantage in fighting warlords for the share of total production controlled by each group. We assume that profits within the occupational groups are distributed equally amongst members, as a consequence of our decision to model homogenous violence specialists. For the production function, we assume a standard one-input production function (see Appendix). As a result, the tax rate and investment in production are jointly determined in the model and an equilibrium emerges where violence specialists switch to the most profitable occupation until payoffs to both occupations are equal – implying that no violence specialist can improve his payoff by switching occupations.

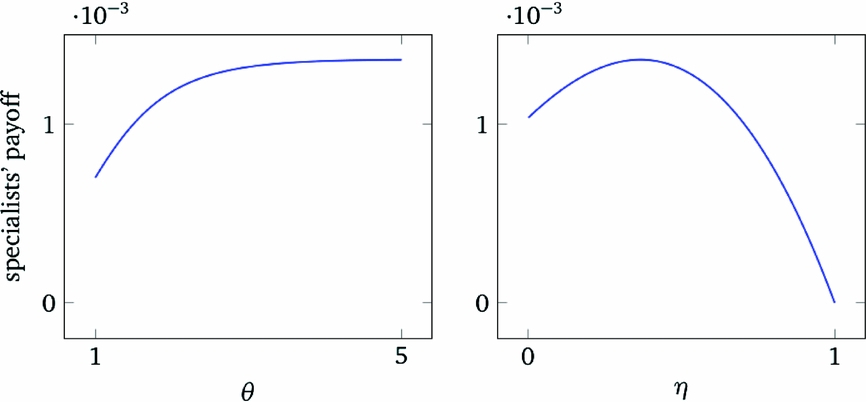

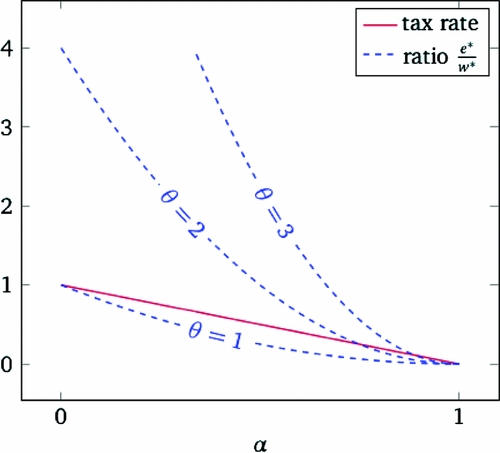

We emphasize three important mechanisms that result from the model. First, incentives for producers to invest in production arise from low appropriation rates and from the marginal product of effort. Second, the elite are willing to impose low tax rates, stimulating producers to increase investments in production, when the returns on such investments are high. Third, incentives for violence specialists to join the elite decrease when the tax rate is lower, implying that net appropriation is generally rather inert and high. The tendency of violence specialists to opt out of the elite follows logically from the fact that the production enhancing effect of a lower tax rate generates higher output and, thus, benefits violence specialists in both categories. On the one hand, this result derives clearly from the assertion advanced by NWW that we need to think of the elite as a composite entity, but, on the other hand, means that we need to emphasize that there is no straightforward incentive for violence specialists to join the elite – contrary to the assumption of NWW. In other words, production and order are trade-offs and the total level of appropriation is generally high, ranging from a situation with high taxes imposed by a strong elite to a situation with low taxes combined with a large group of warlords. These last two results are summarized in Figure 1, with the output elasticity of effort depicted by parameter α and elite cooperative quality by θ (see the Appendix for details).

Figure 1. Tax rate and elite-warlord ratio as a function of the output elasticity of effort α and elite cooperative quality θ (based on model and parameter values introduced in the Appendix).

The model indicates that the interaction between the distribution of violence specialists – as a representation of political order – and economic productivity indeed provides a rather inert system, as one would expect following the argument of NWW. The political configuration allows little room to enhance production – which is discouraged either by high taxes or high appropriation by warlords. Furthermore, our discussion here illustrates that a more productive environment is in itself not a solution to escape this ordeal, since it will induce a tendency towards lower tax rates and, thus, a disincentive for violence specialists to join the elite coalition, resulting in increased insecurity and a negative effect on production.

This apparent deadlock would be avoided as limited access orders mature, or progress towards open access. At the same time, such progress is far from evident, given the internal consistency of limited access orders, so importantly stressed by NWW. Following the discussion in this section, however, the enhancement of the cooperative quality of the elite could play a key role in breaking this deadlock, as it would enable limited access orders to combine political order and welfare to a larger degree than otherwise would have been possible. This is because enhancement of cooperative quality allows a relatively small coalition to control a disproportionally large share of production, and foster production due to limited tax rates at the same time (more extensively: van Besouw et al., Reference van Besouw, Ansink and van Bavel2016), which results in relatively favourable outcomes in terms of production and payoffs. This line of argument fully links up with the emphasis placed by NWW on the institutionalization of organizational structures of the elite, which, they argue, decreases the instability within the elite coalition. In section 4, we will further develop this argument, and suggest that the main effect of a more stable elite coalition in limited access orders is that it generates an advantage to the elite in fighting warlords. Before doing so, however, we contrast the interpretation of organizations offered by NWW with the historical record.

3. Introducing organizations

One of the main points made in Violence and Social Orders, and in North's later work more generally, is the identification of organizations as a separate category of analysis, distinct from institutions. More specifically, the book highlights the role of organizations as crucial elements in the transition from limited to open access orders, which is posited to have taken place in Britain and the United States by 1850, in France by 1880 and in some other Western countries even later. In limited access orders, the number, complexity and size of organizations is limited. In addition, access to these organizations is mostly restricted to the elite. In open access orders, by contrast, the number of organizations is much larger, the right to form them is open to all citizens and access to them is an impersonal right that all citizens possess.

Likewise, organizations play a crucial role in the development of limited access orders, which move back and forth within a spectrum from fragile to mature types. Three ideal types of limited access orders are discerned by NWW (p. 21; see also North et al., Reference North, Wallis, Webb, Weingast, North, Wallis, Webb and Weingast2013: 10–14), each characterized by a different structure and role of organizations. Fragile types have very few organizations that persist over time, including the government, and these are all linked to the personality of their leadership, with the leaders personally connected to the dominant coalition. In basic limited access orders, the government is durable and is the main organization, but some non-government organizations exist, mainly formed and staffed by elite members, and closely and personally linked to the government and the dominant coalition. In the mature form of limited access orders, many organizations outside the government exist and have longer lifespans, but access is still limited to organizations supported by the government and which allow the dominant elite to create rents. So, if a society were to progress along these lines, organizations would become more impersonal, longer lasting and access would become more general, outside government intervention, a process solidified when the transition to open access orders takes place.

What is the exact type of organizations that we are considering here? We follow NWW in their focus on contractual organizations. These are organizations that use both self-enforcing agreements and third-party enforcement, as some contracts between the members may not be incentive-compatible at all points in time and thus need to be enforced. The contractual organizations mentioned by NWW include units of government (states, municipalities); but also business organizations, corporations and partnerships, religious and charitable organizations, and cooperatives.

We diverge from NWW, however, regarding two of their additional assumptions. First, they assume (p. 20) that in limited access orders these contractual organizations are normally founded by the elite and require the structure of consent established within the elite. Second, they argue that contractual organizations rely on third-party enforcement and function only with the explicit support of the state (p. 7).

We question both assumptions on the basis of the recent historical literature. First, it is becoming increasingly clear how organizations, according to the same definition, may also have developed, and actually were developed, from below. That is, by ordinary producers and not only by violence specialists. Examples of such organizations are guilds, town communities, village communities and charitable organizations, which have been founded by the thousands in Western Europe from the 11th century onwards (De Moor, Reference De Moor2008; Epstein, Reference Epstein1991: 50–62 and 130–135). The main actors within these organizations were merchants, traders, retailers, craftsmen and peasant farmers. They mostly owned the means of production (land, capital goods) and worked independently but were not violence specialists or elites. Their organizations, operating at the local and regional level, and sometimes forming regional networks, were perpetually lived, contractual organizations. Enforcement was organized internally through elaborate systems of administration and jurisdiction for those – relatively numerous – instances where cooperation within the organization was not incentive-compatible for all members. This is testified by the huge numbers of archives containing all kinds of complaints, conflicts and forms of litigation between members of these bottom-up organizations and settled by internal bodies or community authorities. The guilds (which are surprisingly not discussed in NWW, apart from one single sentence) often took on responsibilities in contract enforcement, a role supplemented or sustained by that of the public authorities of town communities (Epstein, Reference Epstein1991: 80–91). Some scholars stress the independence of the guilds in fulfiling this role (Greif et al., Reference Greif, Milgrom and Weingast1994), whilst others stress the reliance of the guilds on town communities (Ogilvie, Reference Ogilvie2014: 177–179). Both cases, however, support our point because the same town communities in Western Europe were in fact also largely bottom-up organizations, with elaborate systems of enforcement that mostly did not require the intervention of the state even if many rules were not incentive-compatible at all times.

This leads us to the second observation, that the roles of these organizations were not always dependent on the support of the state. This is in contrast to the assumption by NWW. A clear example is given by town communities in late medieval Western Europe. Their structure and role are incompletely represented in Violence and Social Orders. Town communities are discussed by way of a single case – Lille in the 18th century – using a single study. On the basis of this, NWW suggest that these communities were only halfway on their path to perpetual life as corporate identities and impersonality, and only functioned as a result of the recognition and support of the state, in this case the French king (NWW: 70–71). Their example is ill-chosen, however, because it is from an era in which the heyday of the independent town communities – that is, the 13th to 16th centuries – was long over and from an area – the north of France, just conquered from the Low Countries, or Flanders more precisely – where interference by the king was relatively strong. It would have been more logical to have looked at the town communities in the Low Countries and Italy, which acquired a large degree of independence in law-making, jurisdiction, fiscal affairs, finance and administration (van Bavel, Reference van Bavel2010: 110–117). These town communities, just like village communities, acted as independent, perpetual legal bodies, with legal personhood. Their capacity to sell rents and perpetual annuities provides evidence, and it is clear that they did so in large numbers from the 13th century onwards (Tracy, Reference Tracy, Boone, Davids and Janssens2003; van Bavel, Reference van Bavel2010: 186–187 and 190–191).

Returning to our attempt to structure the main elements of the limited access orders: bottom-up organizations had a multiplicity of goals, one of which was to shield parts of production from appropriation by violence specialists. For example, the guilds often had the explicit objective of protecting the living standards of craftsmen in order to enable them to have a decent standard of living, that is, substantially above subsistence level. They did so by strengthening their position vis-à-vis producers who were not members, but also vis-à-vis the extraction and claims by violence specialists (the first stressed more by Ogilvie, Reference Ogilvie2014: 187; the latter by Greif et al., Reference Greif, Milgrom and Weingast1994: 749 and 753). To withstand the claims by violence specialists, they acted as pressure groups and coordinated forms of collective action, using boycotts, strikes and embargoes, and they also formed alliances with other groups and organizations. Town communities were perhaps even more successful in shielding their members from appropriation by violence specialists than guilds, as they negotiated with the dominant elite about the taxes to be paid by their inhabitants and used all forms of economic pressure, obstruction and political cunning to keep these taxes low (Blockmans, Reference Blockmans and Blickle1997).

4. Impacts of two types of organizations

The preceding discussion suggests the relevance not only of top-down organizations formed by elites and explicitly supported by the state, but also of bottom-up organizations, formed by producers and independent of such state-support. In this section, we return to the trade-off between production and order in limited access orders, or the ‘deadlock’ situation observed in section 2. We do so by illustrating the distinct effects of the two types of organizations in limited access orders, using the model of section 2. We stress that our simple parameterization of organizations is meant to illustrate their impact, abstracting away from many other potential effects, rather than to provide a comprehensive analysis of organizations. As argued at the end of this section, alternative interpretations are possible, but these do not impede the current one. We refer to the organizations as described by NWW (p. 20), as ‘top-down organizations’. These are modelled as enhancing the relative fighting advantage of the elite coalition – parameter θ in the control function (see Appendix). An increase in θ increases, the share of production controlled by the elite coalition vis-à-vis warlords – who cannot establish organizations, following from our assertion that their access to resources is insecure because it is contested by the elite coalition and because warlords do not systematically accept and protect each other's resource base. An alternative type of organizations is ‘bottom-up’ organizations. These can be modelled as shielding a proportion of production from appropriation – which is modelled using parameter η, which enters the payoff function of the representative producer (see Appendix). An increase in η increases the share of production that is secured by the representative producer and which therefore cannot be appropriated by the elite or by warlords.

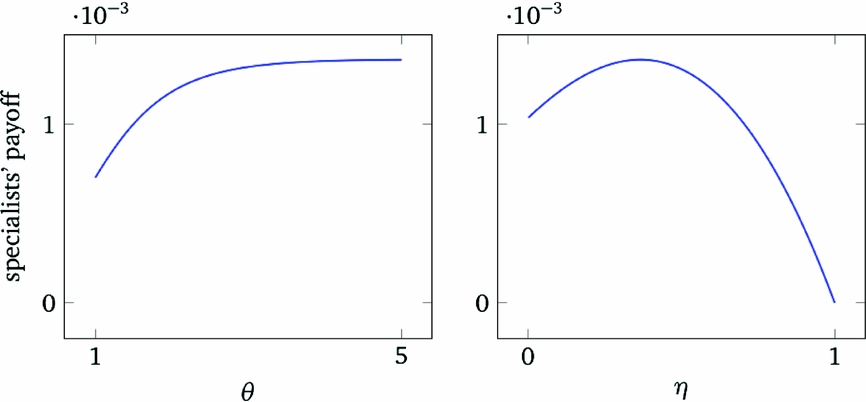

The model outcomes that we focus on include (a) the level of production, (b) payoffs to producers as a proxy of total welfare in society, (c) the total appropriation rate and (d) the size of the elite coalition. Figure 2 illustrates our model results. Values of key model outcomes are displayed as a function of the size (or, alternatively, the maturity) of organizations. The left panel in the figure represents the impact of top-down organizations and the right panel that of bottom-up organizations.

Figure 2. Impacts of introducing organizations on production, welfare, appropriation and elite size. Left panel: top-down organizations (parameter θ). Right panel: bottom-up organizations (parameter η). The model, its main functions and parameter values used are provided in the Appendix.

Figure 2 shows that both types of organizations have a comparable impact on key model outcomes. Summarized, as θ or η increases, (a) production increases, (b) welfare increases and (c) the appropriation rate decreases. Yet, there are also two important differences. First, the size of the elite coalition, and therefore the share of production controlled by the coalition, is responsive to θ, but not to η. That is, top-down organizations facilitate an increase in the size of the elite coalition, whilst bottom-up organizations do not. Second, production and welfare increase at a decreasing rate with θ but at an increasing rate with η. That is, top-down organizations boost production but their impact reduces as organizations grow. Conversely, bottom-up organizations become more important for production and welfare as they grow.

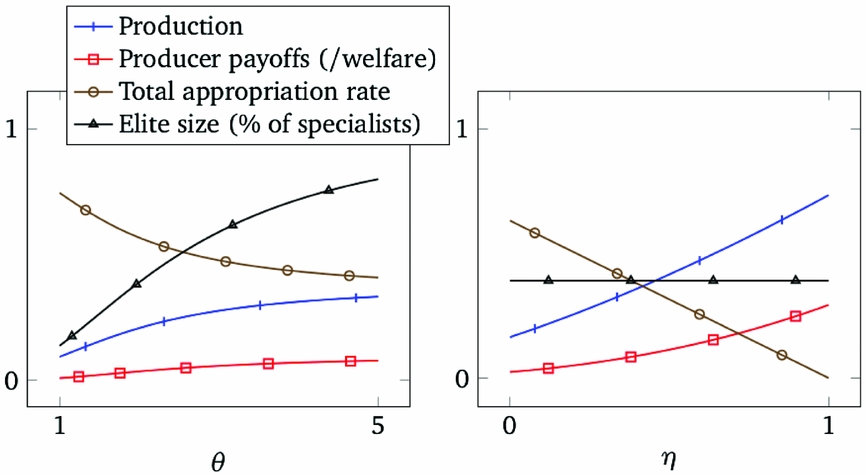

A third difference between the two types of organization is illustrated in Figure 3, which displays violence specialists’ payoffs under the two types of organization. To appreciate the figure, recall that by our mechanism for occupation choice, elites’ individual payoffs are always equal to warlords’ individual payoffs. The figure illustrates that these payoffs increase in θ but are hump-shaped in η. That is, growth in top-down organizations always facilitates higher payoffs for the elite coalition (and warlords) but at some level of bottom-up organizations, violence specialists’ payoffs start to deteriorate. Before this point is reached, however, specialists’ payoffs also increase in η, thus forming a possible component in clarifying why violence specialists would allow the rise of bottom-up organizations, at least to a certain extent. Eventually, specialists’ payoffs converge to 0 as η tends to 1. The explanation is that, at this point, the entire production is secured by the representative producer and cannot be appropriated by the elite or by warlords. Since elites and warlords have no other sources of income in our model, zero appropriation implies that their payoffs drop to 0.Footnote 1

We stress four final considerations in the interpretation of our model results. First, note that the increase in payoffs to the elite coalition as top-down organizations grow – or the increase in producer welfare as bottom-up organizations grow – does not imply that this growth will happen automatically. The development of organizations is costly and so there is a trade-off between costs and benefits of organizations. Adding a specific functional form for costs of organizations would allow us to derive a specific value for organization size; i.e. a specific point on the horizontal axis of Figures 2 and 3. Second, in the long run organizations may alter the production structure, thereby affecting the functional forms or parameterization of the production functions. Third, note that we have assessed top-down and bottom-up organizations separately, whilst certainly a combined analysis is possible. A full treatment of one or both considerations would not, given the simple setup of the model, provide insights beyond those presented here. Fourth, it is evident that alternative interpretations of our organization parameters are possible, or even attractive. The cooperative quality of the elite θ, may increase with an elite-advantage in conflict technology or political legitimacy. Also, the capacity of producers to shelter part of their produce – η – would be influenced by geographic conditions and their choice in producing certain crops or goods. Obviously, such alternative interpretations do not impede our interpretation, but they are relevant for comparative research on limited access orders.

5. Organizations and the historical chronology

The preceding section substantiates the large effects of organizations, in line with NWW. It brings us closer to understanding the role of organizations in forming the incentives of the agents and structuring the maturation of some limited access order societies and their transition to open access. This transition, according to NWW, was confined to some Western countries and happened only late in history, the first societies undergoing this transition being Britain and the United States, and not until 1850. It is only then that organizations, that is contractual organizations, have become impersonal, perpetual and with general access, and outside governmental interference. The transition, in their view, was preceded by a process in which mature limited access orders with more complex organizations, growing impersonality and more general access into the coalition developed in the 16th–18th centuries, as in England and France (pp. 69–72).

Section 4 endorses the stress put by NWW on the important role of organizations, but what about their chronology of the development of organizations? As discussed in section 3, the historical evidence suggests that their chronology on this point may not be entirely correct, as a result of two assumptions they make. According to their view, (a) the contractual organizations are in principle founded by the elite amongst the violence specialists and (b) they function with the explicit support of the state (NWW: 7 and 20). In section 3, we have used the recent historical literature to question these assumptions and to introduce a second category of organization: the bottom-up organizations formed by producers. Introducing them not only has large effects on the outcomes (as shown in section 4), but also affects the chronology of developments.

We have noted that guilds, town communities, village communities and charitable organizations were founded in large numbers in Western Europe from the 11th century onwards (De Moor, Reference De Moor2008). Their heyday as independent bodies was in the 13th to 16th centuries, and can be situated more specifically in Italy and, next, the Low Countries, where their position was strongest and most pronounced, as most clearly with the town communities (Jones, Reference Jones1997; van Bavel, Reference van Bavel2015).

It is here that we can also best observe the independence of bottom-up organizations. The position and capacities of the town communities were often only recognized by some overlord in order for him to pretend to have some position, at least nominally, but without practical effect. The cases where the overlord tried to really effectuate some nominal or pretended right often led to long resistance and even open violence, and in most cases, the town communities were the victors (Blockmans, Reference Blockmans and Blickle1997: 259–267). It is relevant to note that ordinary producers, organized within guilds, town communities and village associations, and acting by way of an organization or a collective, sometimes came to muster large-scale violence. As such, they became able to withstand violence specialists, especially those outside the dominant coalition but at times even the dominant coalition itself. A major example is the Battle of the Golden Spurs, in 1302, as the feudal coalition headed by the French king and 2,500 well-trained noble knights were defeated by a Flemish army composed of militias of guilds, towns and villages (van Bavel, Reference van Bavel2010: 120–121). This victory in its turn greatly strengthened the legal and military position of the guilds and the autonomy of the town communities; an effect radiating through all of the Low Countries.

The Battle of the Golden Spurs was a spectacular event, but more generally the period of the 11th to 14th centuries saw a multitude of smaller events or mutinies, as organizations formed by ordinary people were able to withstand violence specialists and dominant elite coalitions (Prak, Reference Prak2015: 102–110; van Zanden, Reference van Zanden2009: 50–53). In this way, producers were still not violence specialists, but they were sometimes successful in establishing organizations that develop the capacity of large-scale organized violence.

The subsequent period, the 15– to 18th centuries, saw various developments that gradually and intermittently changed this picture. We will tentatively indicate these developments here. First, the military balance started tipping to the princely overlords, that is, to the dominant elites, who were able to deploy ever larger financial and military power (Blockmans, Reference Blockmans and Blickle1997: 267–271). This is where the changes in military technology and warfare of the 16th and 17th centuries, labelled the military revolution (Parker, Reference Parker1996), come in. They were not a driving force that inexorably led to state formation or changes in social orders (as noted by NWW: 177–181, on this point arguing against Tilly, Reference Tilly1993) but it was a factor that in this specific context gave dominant elites and their state organizations an edge over bottom-up organizations. This happened even across state boundaries, as in Northern Italy, where town communities were defeated by the large armies of the French and Spanish kings and subsequently were eroded by new royal rule (Tilly, Reference Tilly1993: 77–79). Second, town communities and guilds, or their leaders, in many instances became co-opted by or integrated into the dominant elites. Third, some bottom-up organizations and their leaders increasingly acted as violence specialists themselves, able to organize large-scale violence, and aimed at appropriating shares of production at the expense of rural producers – e.g. the town community of Florence and its leaders versus its rural surroundings – or competitors – the Hanseatic League versus rival merchants (Greif et al., Reference Greif, Milgrom and Weingast1994: 773; Ogilvie, Reference Ogilvie2014). One could argue that an intermixture of top-down and bottom-up organizations took place in this period.

As observed in section 4, and suggested by our reading of historical developments in this section, the rise of bottom-up organizations had large effects on the economy; more specifically, it led to a decrease in appropriation and a large increase in production and welfare; and this to a much greater extent than with the rise of top-down organizations. This sped up the developments discussed by NWW and already from a much earlier period than they suggest. An earlier chronology of the economic effects is fully compatible with the newest estimates of GDP per capita. These show that (a) structural, long-run economic growth in Western Europe started much earlier – in the Middle Ages – than assumed in the older literature; (b) growth in the medieval period was most evident in, first, Italy and, next, the Low Countries, that is, the areas where independent non-elite organizations were strongest and (c) growth stagnated where and when centralized, top-down organized states became strongest – e.g. France, Spain, after 1450 – and where the originally bottom-up organizations were integrated into the dominant elite or started to manifest themselves as extractive violence specialists – Italy, after 1400 (van Zanden, Reference van Zanden2009: 240–266; for the newest GDP figures: Bolt and van Zanden, Reference Bolt and van Zanden2014).

Our revision of the role and origin of organizations has consequences for the chronology and the location of the development of limited access orders into gradually emerging open access orders. NWW do not attempt to trace the historical development of limited access orders, since they feel that insufficient historical information is at their disposal (p. 18, note 22). Their discussion of different types of limited access orders with varying degrees of complexity is therefore largely time-invariant, and is based on a distinction between fragile, basic and mature orders (p. 41). Still, they do suggest a chronology, as mature limited access orders with more complex organizations, distinctions between public and private spheres and governments with monopoly control over violence in their view only developed in the 16th–18th centuries, as in England and France (pp. 69–72). More generally, their story is very much focussed on England, a country that progressed from a fragile order in the 11th century to a mature order in the early modern period and made the transition to becoming an open access order first, in the first half of the 19th century (pp. 77–109 and 213–219). Even though NWW stress that their story is not a teleological one, their description for England still breathes some of this air. The preceding discussion here, however, would require us to look more closely at developments elsewhere in Western Europe, where both the rise of independent, contractual organizations and economic growth occurred earlier than in England. It would also require us to focus less on the state level and government or king, and more on bottom-up movements and the organizations formed by ordinary people.

6. Main findings

Our paper follows Violence and Social Orders, by Douglass C. North, John Joseph Wallis and Barry R. Weingast in its focus on the need of societies to control large-scale, organized violence. It concentrates on one of their social orders, the ‘limited access order’, that was dominant in most of history and still is today. In this order, the violence specialists within the elite coalition use their power to extract rents from the rest of the population, and use these rents to hold the coalition and the associated organizations together, whilst they restrict open violence. We follow NWW by discussing the elite as a composite entity and we follow them in their emphasis on the role of organizations.

Next, this paper tried to offer a better understanding of the incentives of the actors, the role of organizations in this process and its chronology. It does so by using a formal model, inspired by the conceptual approach by NWW and by including an explicit treatment of production. The results show that incentives to produce for the representative producer are a bottleneck for reaching high welfare levels in a limited access order. More specifically, in this order, high welfare levels are only possible with high levels of production and a low total appropriation rate. However, these two properties are trade-offs within the limited access order: high levels of the output elasticity of effort entail high rates of appropriation.

Introducing organizations into the model has large effects on outcomes, thus confirming the emphasis put by NWW on the role of organizations in development. We diverge from NWW, however, regarding their classification of organizations in limited access orders. Based on historical research, and contrary to NWW, we argue that these (contractual) organizations are not always founded by the elite and do not always rely on third-party enforcement and function with the explicit support of the state. This reading of the historical record has led us to introduce another type of organizations, the bottom-up ones, which are founded by non-violence specialists and shield parts of production from appropriation by violence specialists, aside from the top-down ones presented by NWW.

Making the distinction between organizations developed by the elite and bottom-up organizations, has important implications for the incentives of violence specialists and production levels. The organizations of the elite improve their position relative to warlords – the violence specialists operating outside the elite coalition – whereas organizations of producers are used to shield part of their production from appropriation by violence specialists. The two types of organization have a comparable impact in terms of increasing production, increasing welfare and decreasing appropriation rate, but there are also two important differences. First, top-down organizations facilitate an increase in the size of the elite coalition, whilst bottom-up organizations do not. Second, top-down organizations boost production but their impact reduces as organizations grow, whilst bottom-up organizations become more important for production and welfare as they grow.

These insights lead us to adjust the account and the chronology of developments discussed by NWW. In their account, they focus mainly on England, a country that progressed from a fragile limited access order in the 11th century to a mature limited access order in the early modern period and made the transition to open access in the first half of the 19th century. In this process, they argue, top-down, contractual organizations, linked to the state, played a main part. Other countries, including the United States and France, followed this path somewhat later.

We would say, however, that alongside this process, there was an important role for bottom-up organizations, including town communities and guilds, which developed all over Western Europe, including England, from the 11th century onwards. They operated at the local and regional level and functioned often to a large extent independently of the state, as seen most conspicuously in the Low Countries and Italy during the 13th to 15th centuries. This is exactly where, according to the newest GDP per capita estimates, economic growth in this period was most pronounced.

In the 15th to 18th centuries, connected to the rapid changes in military technology of the period, these independent bottom-up organizations largely lost out to the princely overlords and the state organizations. In Northern Italy, this happened due to the interference by the French and Spanish kings, showing how different limited access orders could interact across state boundaries; an aspect that in future research would deserve more attention. In this period, the bottom-up organizations largely lost their independence from the state and their leaders were often integrated into the dominant elites. Where this happened most conspicuously, as in France, Italy and Spain, the economy in this period most clearly stagnated. At that point, the Netherlands and England diverged from the rest of Western Europe. This divergence happened both in terms of economic development, with the two countries sustaining their high levels of welfare whilst other parts of Europe experienced low and declining welfare – Europe's little divergence discussed by Allen (Reference Allen2001) – as well as political development, with especially England becoming an open access society along the lines sketched by NWW. Even though the latter stages thus conform to the reconstruction of NWW, we would thus stress that bottom-up organizations played a crucial part in the maturation of limited access orders. More speculatively, we would suggest that the same was the case in the transition to open access orders in the 19th and 20th centuries, as there was a similar wave of formation of new and independent, bottom-up organizations, including trade unions, cooperatives, mutual insurance companies and political organizations, which fulfilled a similar role, not only at the local and regional but now also at the national level, within the framework of the nation state.

Our contribution thus strengthens the more abstract and conceptual reasoning by NWW. It has, using a formal model, substantiated the insights gained by NWW, especially concerning the incentives of actors and the implications of organizations. Furthermore, our discussion of the historical record refines their treatment of organizations by demonstrating the prevalence of bottom-up organizations independent of the state that reduced the rate of appropriation by violence specialists. This leads us to suggest that the start of relevant developments within limited access orders in Western Europe must be dated earlier in time, more particularly in the 11th century.

Acknowledgements

We thank Maarten Prak, Jip van Besouw, Mark Sanders and the participants of the Economic and Social History seminar at Utrecht University for their comments on an earlier version of this paper. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support offered by the European Research Council for the project ‘Coordinating for life’ (ERC Advanced Grant no. 339647).

Appendix 1 The model

In this Appendix, we first describe the maximization problem for the agents in our model and the equilibrium solution. We subsequently provide functional forms for the control function and the production function which we use to derive the results illustrated in Figures 1 and 2. Both functions satisfy the properties described in section 2. We refer the reader to van Besouw et al. (Reference van Besouw, Ansink and van Bavel2016) for additional model details and a detailed equilibrium analysis.

In the model, violence specialists and the representative producer interact according to the three stages described in Section 2:

(1) Violence specialists choose their occupation, elite or warlord;

(2) The elite coalition collectively decides on the tax rate; and

(3) The representative producer chooses its production level.

Using subgame-perfection, we solve the model backwards, with each agent maximizing his payoffs. The payoffs of elites and warlords depend on the share of total production they control, and the rate of appropriation they can impose over this share. Following from our assumption that violence specialists are homogenous, total income of the elite (warlords) is distributed equally over all elite-members (individual warlords). The payoff of the representative producer depends on the share of his production that is not appropriated minus the cost of effort. The payoff functions for elites, warlords, and the representative producer are as follows:

$$\begin{equation*}

\begin{array}{l} {\pi _{{\rm{elite}}}} = \left( {\frac{1}{e}} \right)\tau \rho \left( {e,w} \right)\left( {1 - \eta } \right)Y\left( \phi \right)\\

{\pi _{{\rm{warlord}}}} = \left( {\frac{1}{w}} \right)\left( {1 - \rho \left( {e,w} \right)} \right)\left( {1 - \eta } \right)Y\left( \phi \right)\\ {\pi _{{\rm{producer}}}} = \left( {1 - \tau } \right)\rho \left( {e,w} \right)\left( {1 - \eta } \right)Y\left( \phi \right) + \eta Y\left( \phi \right) - \gamma \phi \end{array}

\end{equation*}$$

$$\begin{equation*}

\begin{array}{l} {\pi _{{\rm{elite}}}} = \left( {\frac{1}{e}} \right)\tau \rho \left( {e,w} \right)\left( {1 - \eta } \right)Y\left( \phi \right)\\

{\pi _{{\rm{warlord}}}} = \left( {\frac{1}{w}} \right)\left( {1 - \rho \left( {e,w} \right)} \right)\left( {1 - \eta } \right)Y\left( \phi \right)\\ {\pi _{{\rm{producer}}}} = \left( {1 - \tau } \right)\rho \left( {e,w} \right)\left( {1 - \eta } \right)Y\left( \phi \right) + \eta Y\left( \phi \right) - \gamma \phi \end{array}

\end{equation*}$$

Parameter τ is the stage-2 tax rate, η is the share of output Y protected from appropriation by bottom-up organizations and parameter γ is the cost of effort to the representative producer. The variables are the number of elites e and the number of warlords w. What is left are the control function ρ(e, w) and the production function Y(ϕ), where ϕ denotes effort.

The control function ρ(e, w) takes two variables and two parameters, the decisiveness of conflict m and the cooperative quality of the elite θ, as inputs and gives the share of production controlled by the elite coalition as output. Given m < 1, there are diminishing marginal returns to group size. Given θ ≥ 1, the elite has an advantage over the warlords in their contest to control production:

The production function Y(ϕ) takes one variable and two parameters, a linear technology parameter β and the marginal product of effort α, as inputs and gives the level of production by the representative producer as output. Note that this one-input production function is functionally equivalent to a Von Thünen production function, which in turn, is equivalent to a linearly homogeneous Cobb–Douglas production function with inelastic supply of labour (Lloyd, Reference Lloyd2001), with exponent 1 − α for labour and α for capital. However, our one-input model does not require these restrictive conditions on the production function as would be required for an extension to a two-input Cobb–Douglas function. Our specification allows us to focus on the representative producer's decision variable, effort ϕ which is elastically supplied:

A solution to this model follows from optimizing the decision variables, effort ϕ for producers and tax rate τ for elites, which yield response functions with which the model can be solved. For η = 0, that is, excluding the impact of bottom-up organizations, van Besouw et al. (Reference van Besouw, Ansink and van Bavel2016) provide analytical results of this model. Key outcomes are the elite size and production level. The equilibrium elite size is a function of parameters α, θ and m, as well as parameter V ≡ e + w, equal to the (fixed) number of violence specialists:

$$\begin{equation*}

{e^*} = \frac{V}{{{{\left[ {\left( {1 - \alpha } \right)\theta } \right]}^{\frac{1}{{m - 1}}}} + 1}}

\end{equation*}$$

$$\begin{equation*}

{e^*} = \frac{V}{{{{\left[ {\left( {1 - \alpha } \right)\theta } \right]}^{\frac{1}{{m - 1}}}} + 1}}

\end{equation*}$$

The equilibrium production level is a function of parameters α, β, γ, θ, and m:

$$\begin{equation*}

{Y^*} = \beta {\left( {\frac{{\ {\alpha ^2}\beta }}{\gamma }} \right)^{\frac{\alpha }{{1 - \alpha }}}}{\left( {1 + \left( {1 - \alpha } \right){{\left[ {\left( {1 - \alpha } \right)\theta } \right]}^{\frac{1}{{m - 1}}}}} \right)^{\frac{\alpha }{{\alpha - 1}}}}

\end{equation*}$$

$$\begin{equation*}

{Y^*} = \beta {\left( {\frac{{\ {\alpha ^2}\beta }}{\gamma }} \right)^{\frac{\alpha }{{1 - \alpha }}}}{\left( {1 + \left( {1 - \alpha } \right){{\left[ {\left( {1 - \alpha } \right)\theta } \right]}^{\frac{1}{{m - 1}}}}} \right)^{\frac{\alpha }{{\alpha - 1}}}}

\end{equation*}$$

From these key model outcomes, other outcomes like producer payoff and the total appropriation rate can be derived. In the current paper, with η ≥ 0, we choose to support our arguments graphically using numerical simulations. Our illustration of results in Figures 1–3 uses parameter values α = 0.6, β = 1.2, γ = 1, m = 0.5, V = 100, η = 0.1 (left panels) and θ = 2 (right panels).