Wartime hunger in princely India

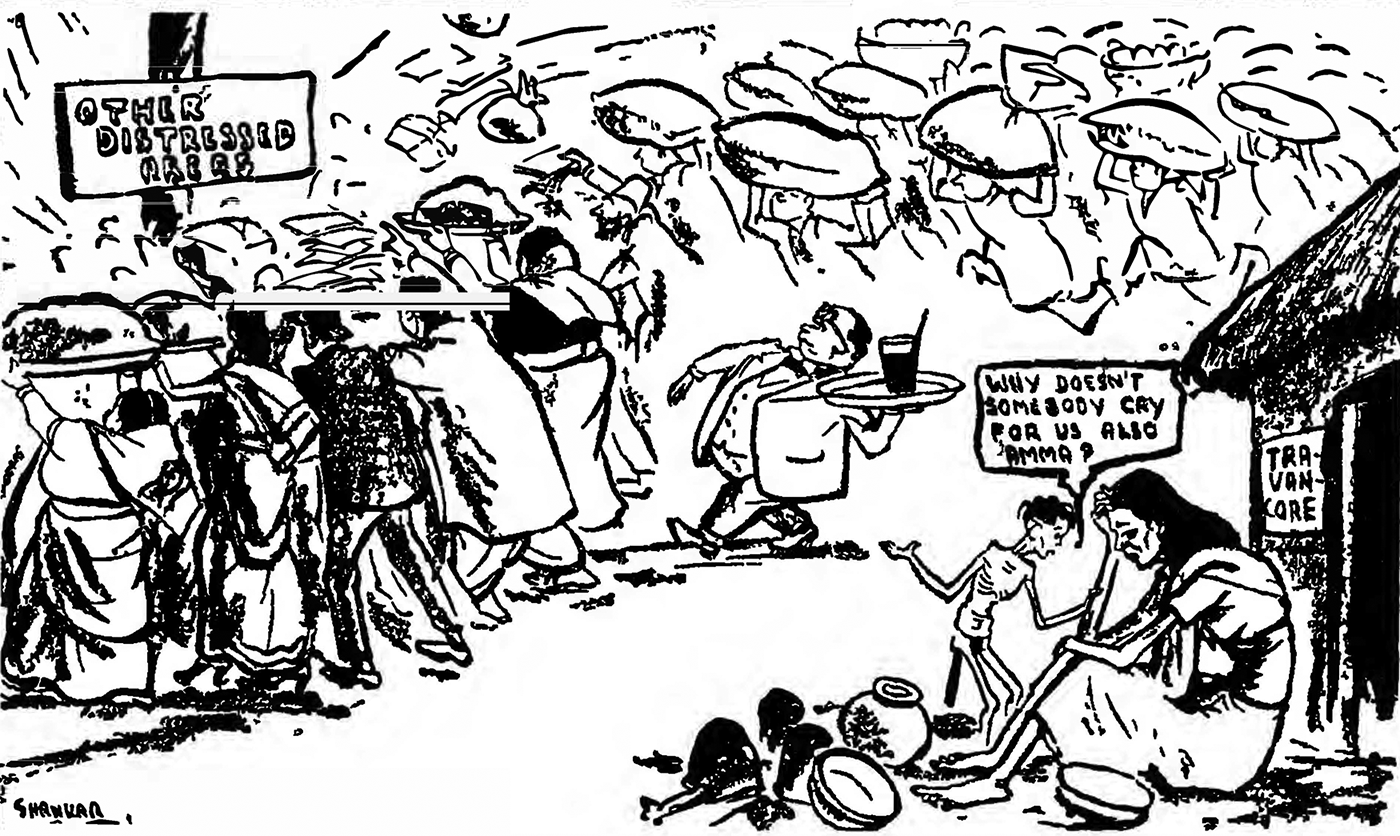

Covering the food shortage across the country for the Hindustan Times in late 1943, journalist and nationalist politician K. Santhanam (1895–1980) lamented that, despite India’s considerable natural resource endowments and successful avoidance of enemy invasion, ‘the cry of hunger and distress is heard from Trivandrum to Chittagong, One feels angry and bitter at this inexplicable tragedy.’Footnote 1 Santhanam’s booklet of collected articles from that year, Cry of Distress, captured the experience of hunger across India. Accompanying an article on the princely state of Travancore—the capital of which was Trivandrum—was an image by the country’s most famous cartoonist and Travancore native, Shankar (Figure 1).Footnote 2 Whereas ‘other distressed areas’, as Shankar dubbed them, were being practically inundated with stocks of food from people of different communities (delineated by dress), Travancore was receiving nothing. At the centre of the image, a corpulent waiter dressed in the Western style brings a drink on a platter towards these areas. Outside the hut, an undernourished mother sits with her hand on her head alongside scattered and empty pots and pans. An emaciated child, grabbing her by the arm, asks ‘Why doesn’t somebody cry for us also, Amma [Mother]?’

Figure 1. ‘Why Doesn’t Somebody Cry for Us Also, Amma?’.

The slight hyperbole of the image notwithstanding, it is true that while Chittagong’s distress (and that of Bengal, more broadly) is remembered, that of Trivandrum is forgotten. This is in part because the casualties suffered in Bengal were on a scale greater than those endured in Travancore: three million people out of a population of approximately 60 million—about 5 per cent—compared to what the social worker K. G. Sivaswamy estimated as 90,000 deaths in a population of approximately 6 million (or about 1.5 per cent of the population).Footnote 3 The Famine Enquiry Commission did not use the terminology of famine to describe the events there, although it was unaware of these numbers at the time.Footnote 4 Even Travancore’s diwan (prime minister) C. P. Ramaswamy Aiyar (1879–1966), whom we shall see was far from incentivized to exaggerate the gravity of the situation, would draw comparisons to Bengal, asserting that Travancore’s needs were just as great.Footnote 5 Another major difference was the extent of the food deficit. Whereas the shortage in Bengal was estimated at about 3 per cent, Travancore’s was in the order of 60 per cent as it relied far more on the supply of rice from Burma.Footnote 6 The contrast between this relatively small shortage and the substantial starvation experienced has been an important empirical fillip to Amartya Sen’s celebrated entitlement approach to famine, which has asserted that it was decline in the exchange entitlement to food, or purchasing power, rather than food availability decline that led to Bengal’s distress.Footnote 7 Travancore’s distress was related to the more straightforward—and perhaps less immediately surprising—problem of food availability, although the decline in purchasing power of even the limited available food among certain sections of the population exacerbated the suffering.

Some of the reasons why the ‘cry of distress’ from Travancore was muffled during the Second World War can be gleaned through a comparison with the more well-known events of Bengal. Unlike in Bengal, where Ian Stephens, the editor of Calcutta’s Telegraph newspaper, took the courageous decision to abandon voluntary self-censorship and lay bare the consequences of the unfolding Bengal Famine from August 1943, no equivalent periodical with international circulation reported on Kerala’s food shortage and its consequences.Footnote 8 By contrast, all literature that was possibly offensive to the government was banned in Travancore. Next, migration patterns differed. Travancoreans went to rural and forested Malabar and had no metropolis, like the city of Calcutta, in which to seek refuge. Migration was not necessarily from rural to urban areas. It would have been harder for the casual urban periodical reporter to perceive the extent of the suffering based on arrivals from other parts of the state. Perhaps most obviously, as a princely state generally left to itself, Travancore never had the importance to imperialist or nationalist affairs commanded by Bengal.

The devastation wrought by the Bengal Famine has overshadowed the transformative impact of the food shortage, hunger, and starvation on other parts of the subcontinent during the Second World War. In addition to Travancore and Cochin, food deficit districts sprung up across the Northwest Frontier Province, Bihar, the United Provinces, and the presidencies of Bombay and Madras.Footnote 9 This article builds on recent work that locates the origins of the large-scale management of food procurement and distribution by the Government of India and a point of inflection for a powerful dimension of nationalist discourse during this period.Footnote 10 It suggests that the physical experience of hunger itself was a constituting feature of the Second World War across the subcontinent. Such a regional perspective on the Second World War in South Asia focused on food, disease, and princely politics provides granularity to a nascent historiography focused on the larger units of the nation-state or the Asian empire.Footnote 11

Other than Cochin, its neighbouring princely state, Travancore had by far the greatest proportion of food imports relative to consumption of any region in India.Footnote 12The following pages explore how and why it came to rely on such a substantial amount of imported food to meet its requirements, the manner in which it dealt with wartime supply disruption, and what effects this management had both on its population and the distinctive political future of the region. Princely states shaped their own destinies in domains other than law, language, politics, and health policy during the early twentieth century, the focus of much regional scholarship.Footnote 13 Other such powerful areas include agriculture, food, and industrial policy.Footnote 14 Despite their speedy incorporation into the Indian Union after 1947, these states remained powerful actors well into the 1940s.Footnote 15

This princely unit of analysis is also important in understanding the subsequent history of Kerala, the linguistic state of Malayalam speakers forged out of Travancore, Cochin, and the British-administered Malabar district in 1956. Kerala-level analyses of wartime food management compare the response to Bengal as an instance of great success through popular pressure for rationing. This involves putting together the princely states of Travancore, Cochin, and the British-administered Malabar district and implicitly neglecting the heterogeneity of their challenges and responses.Footnote 16 Such an approach obscures the ways in which taking up the cause of food helped communists to consolidate their legitimacy in Travancore between 1942 and 1945, a region in which they would hold lasting influence and mobilize revolts. Since the 1950s, Communist Party-led coalition governments in Kerala have alternated with those led by the Indian National Congress (INC) and defined a uniquely progressive state policy.Footnote 17 Their history of ascent in Travancore has been distinct from other areas of Kerala.

Whether or not the events of 1942–3 constitute a famine according to the definition of social scientists today is perhaps impossible to ascertain.Footnote 18 There is simply inadequate quantitative evidence to make an assessment one way or another. Instead, the pages that follow seek to capture the events, experiences, and historical memory of an event described by certain parties as a famine.Footnote 19 To do so, this article employs a wide range of sources. Woven together with materials from formal archives and newspapers, assembly debates, contemporary economic surveys, and biographies are observations from memoirs and translations of historical fiction from writers with intimate knowledge of these times.

The five sections of this article proceed in a broadly chronological fashion. Informed by Utsa Patnaik’s injunction to take a long view in understanding how food availability shapes groups’ vulnerability to starvation, the first section suggests that the long-term causality of Travancore’s wartime food shortage lies in the transformation of Travancore into a cash crop economy dependent on Burma for its rice supply.Footnote 20 Next, the article shows how the politics of the region developed in the early twentieth century, profoundly informed by its distinctive social structure and monarchy. The following two sections illustrate how the food shortage was handled and what consequences it created. They suggest that the particular, centralized pattern of governance in Travancore and the tense political dynamics contributed to the failures of wartime food policy. Disease, corruption, and starvation ensued. Finally, the article points to how the wartime and immediately postwar food situation contributed to the consolidation and agenda of Kerala’s communist politics and the eclipse of princely rule.

European contact and socioeconomic change: A local history of global capital?

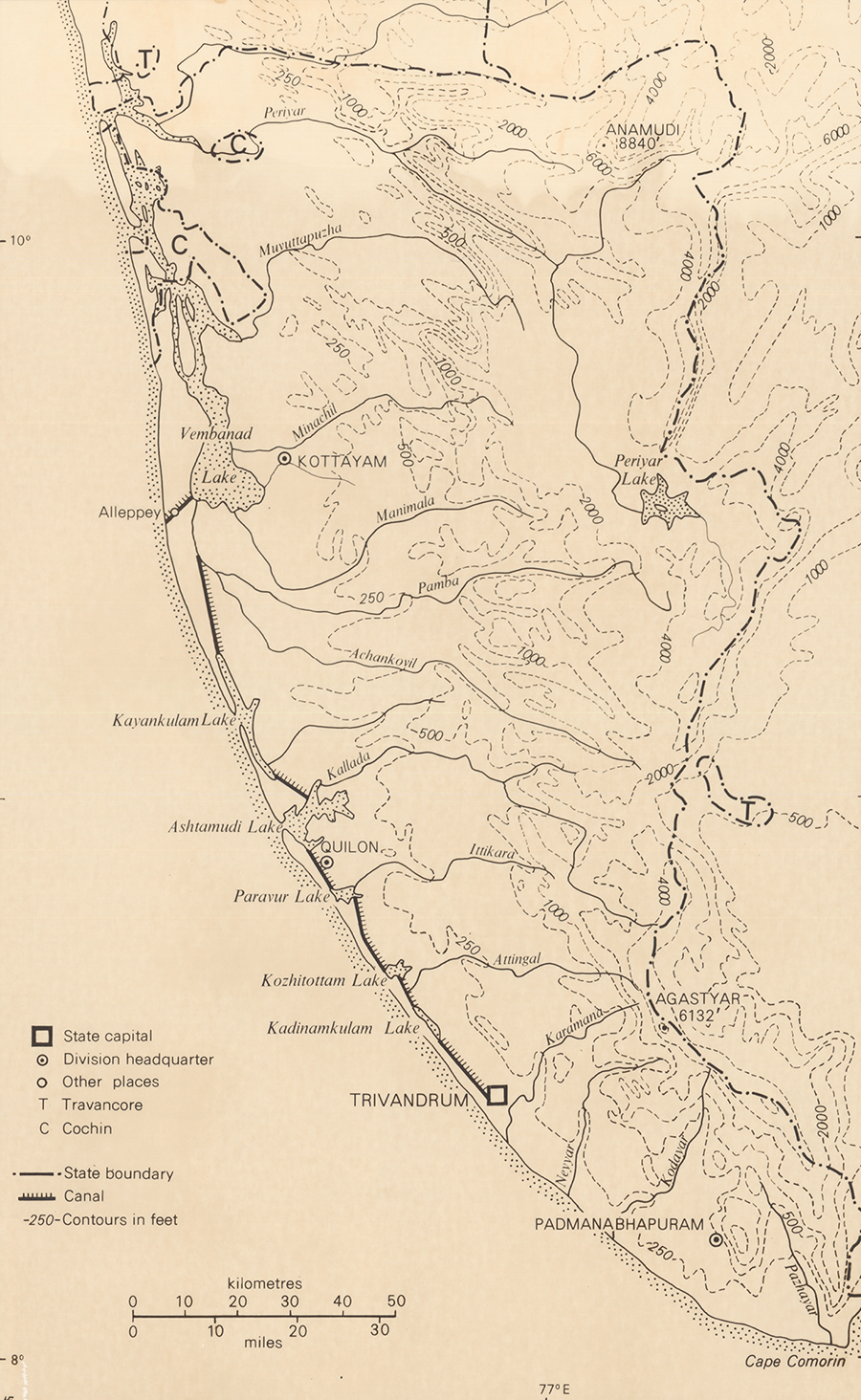

Wedged between the Arabian Sea and the Western Ghats, the princely state of Travancore measured approximately 7,600 square miles. It was blessed with a tropical climate and heavy rainfall (see Figure 2) that allowed the pursuit of a thriving agriculture. By the 1930s, the state sustained a population of approximately six million.Footnote 21 Christianity came to the state in the first century ce, and Islam traced its origins to the early modern period.Footnote 22 As of the 1931 Census, the population was 62 per cent Hindu, 31 per cent Christian, and 7 per cent Muslim.Footnote 23 From the early nineteenth century, the maharaja of Travancore recognized British paramountcy, which constituted the payment of a subsidy in exchange for military protection. After Queen Victoria’s proclamation of 1857 recognizing the dignity of princes, the state moved to a pattern of indirect rule. The British evinced less interest in the specific concerns of local administration.Footnote 24 In this way, Travancore continued to fit into the logic of Anglobalization, abetted by state policy.

Figure 2. Map of Travancore, circa 1900.

Travancore’s integration into the world economy as an agricultural exporter from the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth centuries profoundly reordered the state’s social and economic relations. The state became wealthy, although its fortunes rose and fell with the tide of global markets. Equally, some communities in its multi-religious society prospered while others declined. Even though much of Travancore’s export produce went to other parts of British India, goods like coir had overseas markets as far away as Europe and North America.Footnote 25 Furthermore, the price determination of its cash crops, even in the subcontinent, was tied to the forces of global supply and demand. Thus, Travancore experienced its own distinctive version of what Tariq Omar Ali has called ‘local histories’ of global capital.Footnote 26

Distinct from neighbouring Madras presidency and princely Cochin, in Travancore the state owned almost half of cultivated (sircar) lands. Two crucial pieces of legislation helped create a broader basis for prosperity. The Edict of 1818 freed waste lands from tax for the first ten years and granted favourable tenure thereafter. It was hardly a coincidence, then, that between 1821 and 1911, the area under cultivation increased by 166 per cent.Footnote 27 The second piece of legislation, the Proclamation of 1865, granted senior tenants on sircar lands effective property rights and reduced the land tax.Footnote 28 This broader base for ownership and cultivation limited the number of agricultural labourers to just about 10 per cent of the population by the turn of the twentieth century.Footnote 29 Travancore became ‘par excellence a land of smallholders’.Footnote 30 This is not to say, though, that the region was free of caste-patterned exploitation of labour. Although formal slavery was abolished in the 1850s and forced labour in 1865, agriculture continued to rely on the dependent labour of workers typically hailing from the lower-caste Ezhava and Untouchable Pulaya or Parayar castes.Footnote 31

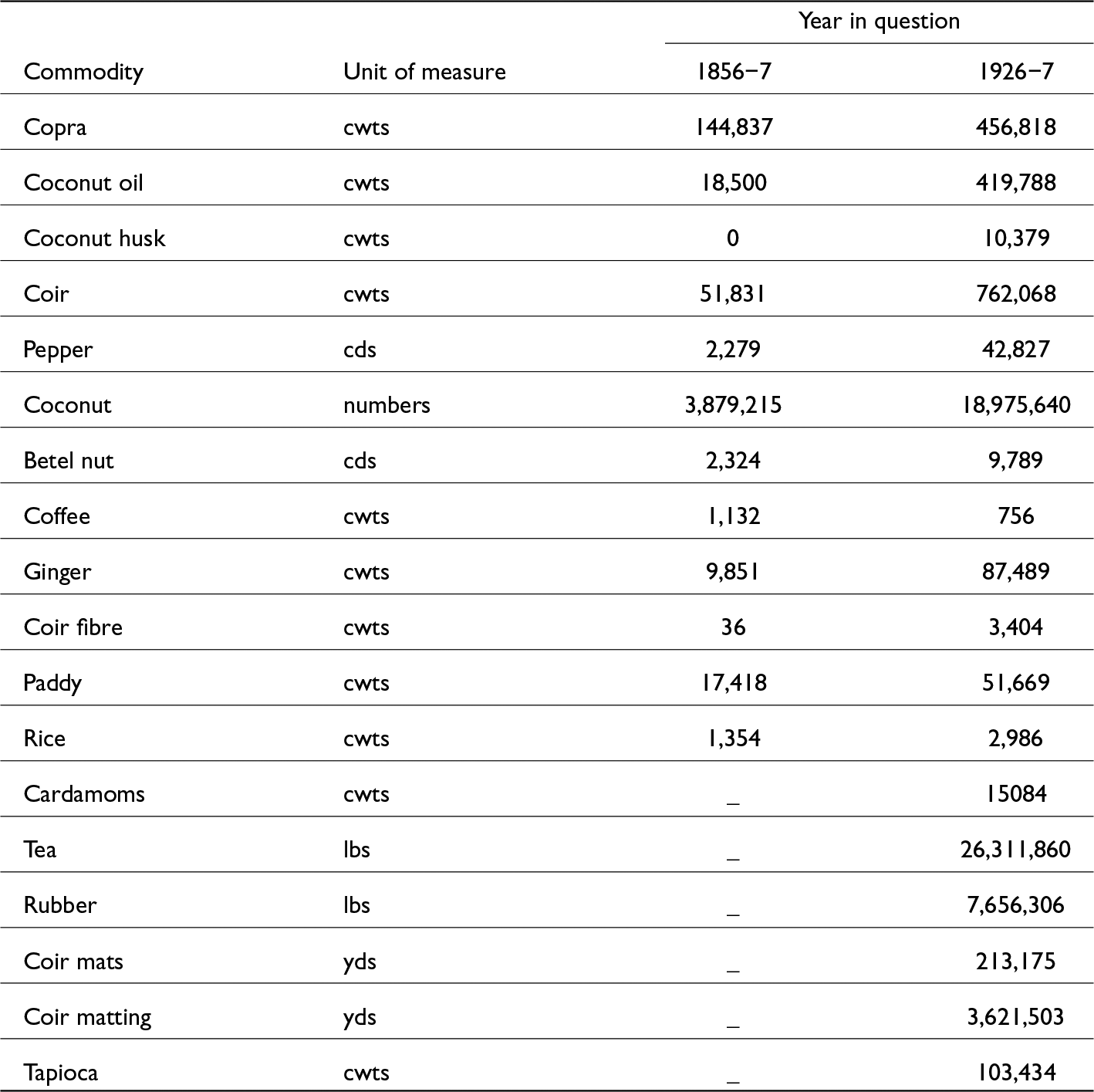

British contact in the nineteenth century contributed both to the development of cultivation for export and the emergence of Christianity as a proselytizing faith.Footnote 32 Cash crop cultivation began seriously from about the 1850s. It expanded substantially after the maharaja cancelled the duty on various state trading monopolies and abolished trade restrictions with the British signed under the terms of the 1865 Inter-Portal Trade Convention.Footnote 33 Subsequently, both the British and natives began to cultivate a range of crops for export. Coconut and its related products like coir became the chief export.Footnote 34 Other major export crops included tapioca, rubber, rice, paddy, coffee, tea, ginger, and pepper.Footnote 35 Travancore also became the major plantation district in South India, with over 62,000 acres of rubber, 75,000 acres of tea, and 48,000 acres of cardamom plantations in the state by 1931.Footnote 36 A large migrant workforce from the Madras presidency worked on these chiefly British-owned holdings.Footnote 37

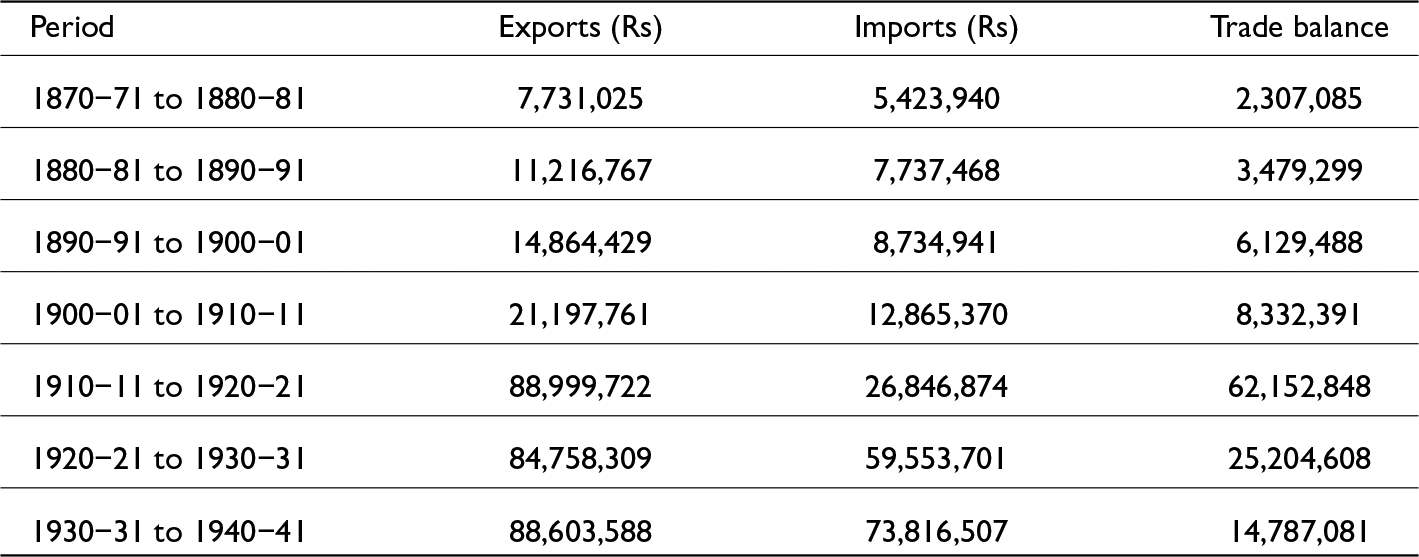

The export statistics given in Table 1 indicate the scale of the change that integration into the world economy through cash agriculture brought to Travancore.Footnote 38 By the 1920s, Travancore was exporting 23 times as much coconut oil, 15 times as much coir, and almost five times as many coconuts as in the mid-1850s. Millions of pounds of tea and rubber, and millions of yards of coir mats left the state each year. This brought greater revenue (see Table 2) that more than paid for import requirements. Led by agro-processing, Travancore began a process of state-facilitated industrialization. An ambitious series of public works financed from tax revenues complemented this process.Footnote 39

Table 1: Exports from Travancore (quantities).

Source: Travancore Administration Report; Statistics of Travancore.

Table 2: Trade balance of Travancore (decadal averages).

Source: P. G. K. Panikar, T. N. Krishnan and N. Krishnaji, Population Growth and Agricultural Development: A Case Studv of Kerala (Rome: FAO, 1977), p. 11.

The transformation of Travancore’s political economy was part of wider processes of regional differentiation based on comparative advantage that developed in a connected imperial economy across the Bay of Bengal, linked by flows of capital, commodities, and labour.Footnote 40 Not all the consequences of this interdependence were salutary.Footnote 41 The expanding volume of trade left Travancore more vulnerable to the volatility of global market prices and demand, and altered the composition of the export basket over time. For example, after the opening of the Suez Canal, competition from Brazilian coffee and favourable prices for tea led to the substitution of the former for the latter.Footnote 42 Compared to Malabar (34 per cent) and Cochin (20 per cent), the adjacent regions, cash crops consumed a larger percentage of the area under cultivation in Travancore (46 per cent).Footnote 43 The quantity of land under wet cultivation began to approach available limits.Footnote 44 A growing population and cultivation for export markets left Travancore a food deficit region. Cash crops were traded for currency, and in turn for rice. Subsistence was therefore tied to global market prices. The state managed to weather the ‘Long Depression’ of the late nineteenth century because large-scale plantation activity for exports had only just started. As the decades went on, and especially from about the 1910s, entwinement with global market conditions increased.Footnote 45

Travancore prospered, especially during the price boom period from 1925–8.Footnote 46 However, from these highs, the advent of the Great Depression the following year reversed the trend. The decline in the prices of its coconut and coconut products was the most significant price movement for Travancore. Instead of reducing its output, the sector responded by increasing production to secure as much cash as possible. Travancore employed an increasing number of labourers but paid them lower money wages.Footnote 47 More straightforwardly, the fall in prices created distress for its rice-growing regions. Agriculturists no longer able to meet their expenses from selling harvest produce entered into debt. Debtors saw the real value of their obligations increase thanks to deflated price levels. Luckily, though, the Depression did not impact on the food security of Travancore at large. A relatively greater decline in rice prices allowed the state to increase external procurement by over 80 per cent (see Table 3). Thus, by the time the Second World War broke out, over half of the state’s rice requirements came chiefly from Burma.Footnote 48

Table 3: Import of rice into Travancore.

Source: Panikar et al., Population Growth, p. 16.

Indebtedness and population increase contributed to a subdivision and fragmentation of landholdings in Travancore, paralleling the Bengal case described by Tariq Omar Ali for Bengal.Footnote 49 Uniquely for Travancore, it was changes in inheritance law that were mainly responsible for this process. Laws passed in the early twentieth century allowed partitioning of the assets of the matrilineal joint family or tharavad system of the dominant landowning community of Nairs, and parallel practices by other landowning communities. In time the nuclear family became the property-owning unit of the family, and the husbands and fathers in the families, rather than the maternal uncles, became proprietors.Footnote 50 Between 1925 and 1940, division of property was greater than ever before, with a majority of landholdings between just a tenth and half of an acre in size. By the eve of the Second World War, the average plot size in Travancore of 3.23 acres was lower than those of the provinces of British India by at least full acre.Footnote 51

The decline of the tharavad system reoriented Nair social life along more patriarchal lines and accelerated the subdivision of plots of land, causing them to become increasingly uneconomic. Thus, the period between the second half of the nineteenth century and the early decades of the twentieth century is seen as one of Nair decline. It is also one of the rise of the lower-caste Ezhavas and the Syrian Christian communities. The Ezhavas’ cultivation of waste land led to their prosperity. The Syrian Christians became major cultivators and purchasers of land.Footnote 52 Social conflict in Kerala emerged within religious communities of the same faith (based on caste among Hindus) and between faiths. In contrast to the Hindu–Muslim tensions that resulted in conflict in much of the rest of India, anxieties about Christianity fuelled inter-religious conflict in Travancore.Footnote 53

The growing prosperity of Syrian Christian families who occupied and improved reclaimed land is among the major themes of Part II of the epic 1978 novel Kayar (Coir) about village life in Travancore’s rice-growing region of Kuttanad: ‘The Christians had taken over,’ its narrator observes.Footnote 54 Named after one of the region’s key agricultural exports, the book’s title also refers to an idiomatic usage of the term ‘coir’, akin to the English ‘yarn’, to connote a story: it has multiple threads and keeps going. Written by the renowned Travancore author Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai (1912–1999) (Thakazhi), the book provides a fascinating perspective on economic and social change from the 1860s to the 1970s from the vantage point of six Nair families and their interlocutors. The transition to commercial agriculture, movements for social reform, and the development of popular politics all feature in the book, which unfolds across several generations. The source material for Kayar came not just from Thakazhi’s life experiences, including his work as a small-town litigator reading tharavad partition documents and property deeds.Footnote 55 A persistent motif of the book is the understanding among Nair families that they were living in the era of the goddess Kali, ‘an era of supremacy for the underdog and the low castes’ when ‘things would go topsy-turvy’.Footnote 56

Christian society's power grew both because of Syrian Christian enterprise and missionary activity. The Church and London Missionary societies established a presence in Travancore from the early nineteenth century onwards, thanks to the intervention of the British Resident.Footnote 57 By a proclamation of 1829, the Travancore administration officially allowed would-be converts to become Christians provided they continued to practise pre-conversion caste norms socially. Although this limited the possibilities for social transformation, it created pressures for the uplift of members of the lower castes, the most active converts.Footnote 58 By the 1930s, converts and their descendants approached a third of the state’s Christian population.

A major missionary activity was the establishment of English-language schools open to those of all castes. Originally, the Travancore government supported them by providing grants for tuition. This was seen as preferable to having low-caste pupils attend the same schools as those of the upper castes.Footnote 59 The broader pressures created by the missionaries also helped prompt progressive reforms by the Government of Travancore in the 1860s. They included the mass introduction of vernacular schools and a requirement of educational attainment for attractive government employment.Footnote 60 From the final decade of the nineteenth century, the state itself assumed greater formal control over educational institutions.Footnote 61 Thakazhi’s novel depicts the increasingly wide spread of education across caste lines by writing of two attempts decades apart to open schools for those from the Untouchable castes. In the first attempt, people from upper castes burned down the school, fearing that education would encourage their Untouchable labourers to seek alternative employment. In the second attempt, once the state had mandated their introduction, the school operated without interruption. Still, the more elite Nair families sent their children to schools in the city which offered greater opportunities.Footnote 62 Travancore educational policy was transformational. Between 1875 and 1941, literacy rose from 6 to 68 per cent. The comparable 1941 figure for British India was just 12 per cent.Footnote 63

European contact ushered in a new epoch in the history of Travancore. Becoming a cash crop exporter in the process of British-led globalization led to great, albeit precarious, prosperity. It strengthened communities that embraced commercial cultivation and backwater reclamation while immiserating the more traditional landowners. Prosperity brought the beginnings of industrialization, and missionary contact created educational and institutional legacies that made Travancore a model state in some respects.Footnote 64 Where the state proved more resistant to change was in responding to the demands of progressive politics that proceeded from the reordering of social and economic relations.

Political organization and reforms in twentieth-century Travancore

Politics in Travancore developed along distinct yet connected lines to those in the provinces of British India. In large part, its distinct political trajectory owed to its theocratic, monarchical form of governance. Most administrative affairs were managed by the diwan (prime minister), an Indian male appointed by the monarch. Travancoreans stood at one level removed from the rule of colonial difference premised on the alienness of the ruling group that proved so important in catalysing anticolonial nationalist resistance in British India.Footnote 65 Even though Travancore had a legislative council (from 1888) and consultative assembly (from 1904), these bodies enjoyed little substantive power.Footnote 66 Flagship parties like the umbrella Indian National Congress (INC) and the Communist Party of India arrived in Travancore long after they had established themseves elsewhere in the country. Political reforms were targeted mitigations of popular pressure that could be easily reversed. In this context, the form that popular sovereignty might take in the future, and Travancore’s relationship to the rest of India, was deeply uncertain.

Localized concerns around social reform and representation, not all-India developments, primarily drove Travancore’s early twentieth-century politics.Footnote 67 Disparate groups came together to contest the particularly rigid, caste-based order of social rules and practices in the Hindu state, as well as the customary privileges of its dominant communities. A major social reform movement sprung up around the Ezhava reformer Sri Narayana Guru (1854–1924), who sought to purify Hinduism of caste and uplift the poor.Footnote 68 The Nairs, an internally stratified group dealing with the social and economic decline of members within their ranks previously discussed, formed a Service Society to consolidate their caste in 1914.Footnote 69 One major assemblage of groups for progressive reform consisted of Ezhavas, Pulayas, Parayas, Christians, and Muslims lobbying the state for greater employment opportunities in prestigious roles in public administration. They were outraged that Brahmans and Nairs held three times their share of government jobs relative to their population.Footnote 70

By the 1930s, influenced in part by mass nationalism in British India, political activity began to concern itself with the form and substance of a future responsible self-government. The federation model brought into being by the Government of India Act of 1935 granted democratically elected legislatures for the provinces of British India while staying silent on the states.Footnote 71 In the face of this contradiction, agitation for responsible government by Travancoreans took a more organized form and became widespread. In 1933, the state introduced a bicameral legislative system with a limited franchise, with special quotas for Muslim, Ezhava, and non-Syrian Christians.Footnote 72

Nevertheless, substantive power continued to vest largely with the monarch and the diwan (prime minister).Footnote 73 The already major influence on state affairs wielded by this figure assumed new proportions when C. P. Ramaswamy Aiyar, until then an adviser to the royal family and law member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council (1931–6), ascended to the position in 1936.Footnote 74 A Tamil Brahman loyal to the royals and inimical to the people, Ramaswamy Aiyar’s appointment met with disappointment by Travancoreans. The British Resident described him as ‘a “superior person” domineering and contemptuous of the common herd…His methods are Machiavellian; he rules by dividing, he bribes with office and other favours, he sets traps for his critics and plays on the weakness of his enemies.’Footnote 75

A signature event of Ramaswamy Aiyar’s first year as diwan was his issuance of the Temple Entry Proclamation. The measure allowed Ezhavas and other Untouchable communities to enter temples, which had been hitherto denied to them. Some see this as an indication of his progressive, modernizing ethos, as the rest of India followed Travancore’s example. In reality, Aiyar, long wary of offending caste Hindus, had only recently changed his views on the matter.Footnote 76 The threat of conversion to Christianity and pressure from Gandhians forced his hand. More plausibly, the measure may be interpreted as an effort to consolidate Hindu society against Christians.Footnote 77

Ramaswamy Aiyar’s stubborn unwillingness to consider demands for responsible government laid bare his less savoury, autocratic tendencies. He worried especially that devolving political power to elected assemblies in the states would pave the way for the entrance of the INC into these legislatures and overwhelm princely power in the federation model. These fears were not without legitimate grounds. In 1938, the INC made a demand for ‘civil liberty’ in the princely states, culminating in the creation of a princely state branch of the INC (State Congress) in Travancore shortly thereafter. Among the issues the State Congress picked up on was the prosecution for sedition and attack on journalists who had written an anti-government article. In one example, the author of a newspaper article about a quota system of communal representation was jailed for 18 months on the grounds of creating communal disturbances. An increase of the fee for press licences created a further impediment to free speech. In May, the State Congress presented a memorial to the maharaja that featured several demands: a Cabinet of Ministers responsible to the legislature, adult franchise, civil rights, freedom of speech and religion, protection from arbitrary arrest, guarantees of a living wage, the dismissal of Ramaswamy Aiyar, and an investigation into his conduct. It culminated in a full-blown Civil Disobedience movement.Footnote 78

Although conducted under the auspices of the umbrella State Congress, a more radical left political movement brewing in the region spearheaded Civil Disobedience. The partial industrialization of the princely state had created a factory population of approximately 330,000 workers by 1920, over a third of whom worked in the coir industry.Footnote 79 Shortly afterwards, following the Russian Revolution, an adherent of Narayana Guru's philosophy named K. Ayyappan introduced the ideas of Marx and Lenin through a triweekly workers’ newspaper. Coir workers came together under the auspices of a Travancore Labour Association (1922) in Alleppey.Footnote 80 By the 1930s, once the effects of the Great Depression began to be felt on Travancore’s export economy, a true working class politics began to develop. It concentrated especially in the coastal Shertallai and Ambalappuzha taluks (an administrative unit, usually a cluster of villages), home to the coir industry.Footnote 81 Over the course of the decade, these coir workers participated in strikes for better wages.

Joining their ranks in left politics were young, educated leaders from groups like the Nair Service Society and student-populated groups like the Youth League who embraced communism. Footnote 82 Labour unions registered as trade unions and won formal recognition of their rights in the Travancore Trade Unions Act of 1937. Together, these groups provided the basis for a workers’ movement. From the following year, strikes were formally organized by committees and volunteer corps in the state.Footnote 83

Although the Communist Party of India, created in 1925, was banned in 1934, its members operated in adjacent Malabar district as they worked within the INC’s newly created Congress Socialist Party.Footnote 84 This was part of a United Front strategy to join with other parties in a common struggle to advance the working class cause. The Malabar leaders, many of them Nairs, worked to create a secular sense of community between workers and peasants and transform rural politics. Depression conditions served them well as they mobilized peasants in unions and organized agitations for tenancy rights and rent remissions.Footnote 85 Over the course of the decade, the Malabar police’s violence against peasants and workers strengthened the resolve of these leaders. At the ideological level, Congress socialists also managed to exert a hold on reading rooms across the district and disseminate progressive literature. This material attacked traditional society and vernacularized communism into an idea of caste equality.Footnote 86 In an environment of increasing literacy across communities, there was uptake of these ideas and a reshaping of the public sphere.

The Civil Disobedience of 1938 was led by the communists across Travancore, Malabar, and Cochin. Malabar communists in the Congress Socialist Party organized a jatha (march) of 40 volunteers to walk the 759 miles from Calicut to Travancore. Along the way, 3,000 volunteers and members of another 500 village and district committees joined them.Footnote 87 Writing many years later in his memoirs, the communist leader A. K. Gopalan recalled it with pride: ‘I have participated in struggles in British India and have led strikes and agitations of mammoth proportions. But the enthusiasm, courage, and general disposition towards agitation that I saw on that day was something that I had never seen before.’Footnote 88 Gopalan and the other communists were arrested and put in jail. Later that year, the labour leaders coordinated the Alleppey General Strike, which was over 20,000 workers strong and lasted 80 days.Footnote 89 This was the first general strike in Kerala’s history.Footnote 90

Arrests and a brutal strangulation of the movement followed. Ramaswamy Aiyar banned the leading newspaper, Malayala Manorama, and warned editors of the serious consequences of publishing anti-government material. Newspapers had their licences cancelled. Finally, after the intervention of Gandhi, agitators withdrew the memorandum in exchange for promises of responsible government. Even still, the damage was done; there would be no true return to normal.Footnote 91

Between the turn of the century and the eve of the Second World War, Travancore politics had evolved from a vehicle for articulating demands for local caste-based change to one connected with national politics and an international ideology that sought nothing less than to remake the world. Class formation, social reform, and the circulation of ideas of progress left Travancoreans willing to court violent suppression to make their demands heard and threw the centuries-old monarchy’s future into doubt.

Travancore in an all-India food crisis

‘Are we not Indians? Why are we treated like this? Is this fair?’ These were some of the questions asked of K. Santhanam, the journalist whose remarks began this article, when he arrived in Travancore in late 1943. If not starving, people were suffering from hunger and malnourishment. They ate anything they could find, including tapioca leaves and coir dust to fill their bellies.Footnote 92 In the order of priority for receiving food supplies from British India, princely Travancore and Cochin came a distant second after Bengal.Footnote 93 The Government of India’s Food Department, which was created only at the height of the crisis, was far from an efficient apparatus and failed to deliver the region adequate stocks. Incoming supply was just one of multiple reasons behind this sorry state of affairs. Santhanam also noted ‘suspicion and distrust’ between the authorities and non-officials that precluded the cooperation required to deal with the food crisis, one that had grown since the Civil Disobedience and under the conditions created by the draconian policies of the Government of Travancore. Although it ultimately took over the wholescale procurement and distribution of food and averted more widespread disaster, a comparison to Cochin reveals that such measures were rolled out with comparatively great hesitation and opacity. Further, it showcases the variations in modes of governance between princely states and their widely divergent consequences.

Across the subcontinent, the princely states pledged their allegiance to the war effort. They took the opportunity to show their support for the Crown and to forestall the possible usurpation of power by the federal authority under the terms of the Government of India Act of 1935. The states sent over 300,000 soldiers to the Indian Army and offered almost £20 million in cash and materials.Footnote 94 The three Madras states of Cochin, Travancore, and Pudukottai were particularly generous. They contributed 150,000 labour units to the war effort. Additionally, these states invested in national savings certificates and defence loans, supplied a field ambulance unit, five mobile canteens, and gave over large quantities of other supplies.’Footnote 95 Among them, Travancore displayed a particular eagerness to put its resources at the Raj’s disposal. The maharaja pledged support a full week before Britain formally entered the war. Some 65,000 Travancoreans left the state to serve in the army.Footnote 96 A further 55,000 joined the Assam Labour Corps.Footnote 97

Beyond its formal contribution, Travancore bore a heavy wartime economic burden. War interrupted shipping routes and brought trade with several European countries to a temporary end.Footnote 98 Across the northern coastal towns of Alleppey, Shertallai, and Quilon, some 25,000 coir factory workers lost their jobs.Footnote 99 According to one estimate cited in the popular assembly, war adversely affected the work of 300,000 people in the coconut and related industries, including those in the informal sector.Footnote 100 Although some were absorbed into the War Supplies Department, they contended with real wage declines and poor conditions as they worked around the clock.Footnote 101

War offered a convenient ruse for Travancore’s unpopular diwan to operate in a particularly draconian fashion. Ramaswamy Aiyar put in place Defence of India Rules, under which anyone could be detained without trial.Footnote 102 Unlike in British India, where the Federal Court struck down the equivalent provisions of the Defence of India Act, the Travancore High Court had no such judicial autonomy.Footnote 103 The diwan also expressed his opinion that too many newspapers operated in the state. He told the Travancore’s Journalists’ Association to cut the number from 70 to 10 around clearly defined lines of policy.Footnote 104 Press communiques issued by the Government of Travancore containing warnings not to publish certain material.Footnote 105 There was no question of Malayala Manorama resuming publication. Sycophancy rather than free speech was encouraged. A particularly egregious example of this were the committees convened around the state to honour the diwan for his Shastiabdapoorthi, or sixtieth birthday. This is a significant event in Tamil society, accompanied by rituals like renewing one's marriage vows. To rehabilitate its image with their Hindu rulers, the Syrian Christian community even proposed erecting a statue in the diwan’s honour to mark the event.Footnote 106

Travancore’s leadership understood that the state’s food deficit left it vulnerable to possible supply dislocations. Anticipating wartime price inflation, the Government of Travancore purchased extra rice from Burma in 1940 and sold it at a loss.Footnote 107 It banned food exports for commercial purposes and fixed prices of imported rice.Footnote 108 Still, as in other parts of India, the prevailing policy wisdom with respect to commodity markets was one of laissez faire.Footnote 109 It was only as the situation worsened over the next few years that the state reluctantly embraced a successively greater role in the procurement and distribution of food supplies. Between the fall of Burma to the Japanese in February 1942 and the declaration of monopoly procurement and rationing by the state in March 1944, a combination of factors internal to Travancore and related to a national food shortage intensified the challenges experienced by the princely state.

A serious food scarcity problem emerged after the fall of Burma to the Japanese in March 1942. This left Travancore, with 250,000 tons of annual rice output, some 367,000 tons short of requirements. Originally, the Madras presidency pledged 176,000 tons to meet the shortfall.Footnote 110 Unfortunately, over the next year, the Madras and Bombay presidencies, as well as the nearby princely states of Cochin and Mysore, began to suffer shortages of their own.Footnote 111 Supplies from Madras dried up by September, leaving Travancore with less than half of what was promised.Footnote 112 Sourcing rice from neighbouring regions could no longer be a viable strategy.

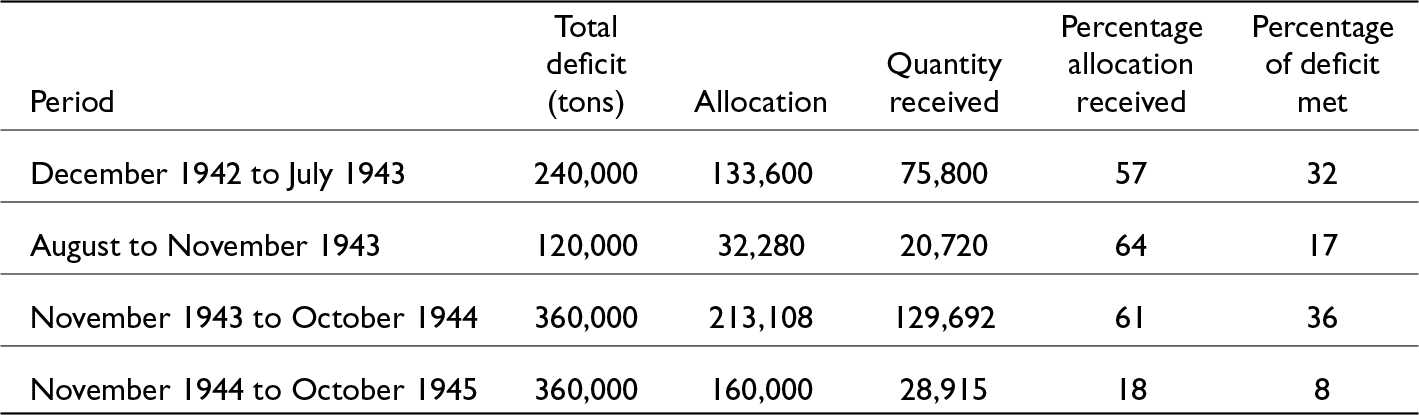

One source of rice for Travancore became the British Government of India’s newly created apparatus to move rice from surplus to deficit regions under a Basic Plan. This new Food Department, fashioned haphazardly, kicked into action as conditions in Bengal deteriorated.Footnote 113 Its priorities did not lie in South India.Footnote 114 Rice travelled by great distances on the already overburdened railways to get to Travancore, creating opportunities for pilferage along the way.Footnote 115 Deliveries of food to Travancore, calculated on the basis of absolute shortages rather than supplies available, fell far short of the pledged amounts (see Table 4).

Table 4: Travancore food deficit, Basic Plan allocations, and quantity received.

Source: Sivaswamy, The Exodus, p. 125. These numbers, reported by the Travancore government, broadly accord with the data presented in N. N. Wanchoo, ‘Memorandum from Food Department to Secretary of State’, 19 November 1943, IOR L/PS/13/1298.

Shortfalls in supplies received from other parts of India forced the Travancore government to pursue multiple local strategies as part of managing the food crisis. First, like other parts of India, the princely state embraced the Government of India’s Grow More Food Campaign. This campaign sought to switch cultivation over from cash to food crops, expand the area of land under cultivation, increase irrigation, and use better seeds to improve agricultural yields. It further provided farmers with various incentives for doing so.Footnote 116 Grow More Food did not amount to very much, because Travancore was already pushing towards the limits of cultivation on its land (see the section of this article titled 'European contact and socioeconomic change'). The state further encouraged the consumption of substitute foods like tapioca and bananas.Footnote 117 Finally, the Travancore government began to regulate and then oversee the procurement and distribution of food across the state.

This was a reactive process of trial and error that culminated in the complete state takeover of every aspect of procurement and distribution of food. It responded to dishonest behaviour by government employees, landowners unwilling to part with their excess stocks, and unscrupulous merchants who sought to sell grains to the highest bidder. Travancore initially required that merchants secure permits for trading and furnish the government with information about their purchases and sales.Footnote 118 This did little to arrest the increase in prices. So, the government created a new office of grain purchasing officers and gave them legal sanction to purchase all stocks of food from landholders at specified prices.Footnote 119 These officers could differ substantially in how much of a landholder’s supply they considered to be in excess. The new basis for government acquisition was thus changed to acreage of holdings.Footnote 120 But this too was discarded because of varying yields across farms. Thus, Travancore embraced a policy of measuring excess stocks on the basis of land rent, which corresponded to yield.Footnote 121 Finally, embracing the idea that ‘maximum benefit can be achieved by direct purchase by Government through their officers from the producing centre itself, and that above all to facilitate the purchase there should be complete control of transport by Government’, the state assumed complete control of the food supply.Footnote 122

In the sphere of distribution, Travancore moved from selective rationing in March 1943 to universal rationing a year later. Originally, officials would ‘dole out small quantities to the most deserving’ and government workers. Rationing was first limited to urban areas, later expanding to rural areas during the course of the year. The needs-based approach to rationing created problems of bureaucratic discretion over who got how much. Further, the double ration given to government servants led to bitter resentment in the populace. So, from August 1943, a blanket ration of 8 ounces (3 ounces of rice and 5 ounces of other grains) was announced for everyone.Footnote 123 This was a tiny amount; the comparable figure for Bombay was 24 ounces and Madras 21.3 ounces of rice.Footnote 124 While it may have sustained life, it did not sustain healthy living.

Travancore’s decision to institute rationing a full year or more before the rest of India may initially seem visionary.Footnote 125 In fact, the director general of the Indian Medical Services cited this as the primary reason that ‘saved this part of India from a Bengal catastrophe’.Footnote 126 The rest of India, of course, did not have a food deficit of over 50 per cent. A more germane comparison is with the neighbouring princely state of Cochin.Footnote 127 Although Cochin benefited from its smaller landmass, population, a smaller proportion of land under cultivation, and access to the deep water port of Cochin Harbour, it also seemed to have understood the seriousness of the problem much earlier and acted accordingly.

From the beginning of the crisis, Cochin instituted a single price for food, rather than different prices for domestic and imported rice. So, there was no problem of cheaper rice going to those who could afford to pay more. Next, from the beginning Cochin’s principle for procurement was based on settlement yields rather than acreage. It was able to get control of 40 per cent of the paddy supply, compared to Travancore’s 25 per cent.Footnote 128 Third, Cochin instituted rationing a full year before Travancore.Footnote 129 Finally, given that its population was heavily rice-dependent, Cochin made special efforts to encourage the consumption of other grains by setting up Cochin restaurants to prepare more palatable meals.Footnote 130

Distinct political dynamics drove Cochin and Travancore’s divergent approaches, the significance of which cannot be underestimated. If the Madras states under British rule wore a ‘hollow crown’, they could still wield substantial power in certain areas.Footnote 131 As we have seen, political power in Travancore was centralized in the unpopular diwan. The observations of the British Resident, who recorded his impressions at some length in 1944, are worth mentioning in this regard. While he credited Ramaswamy Aiyar, a man with a ‘quick brain and arresting personality’, for modernizing Travancore’s administration and rapidly industrializing the state, this came at a price. His autocratic mode of governance had ‘driven all initiative and sense of responsibility from the subordinate staff’. Nobody dared stand up to him. It was no surprise, then, that the legislature was a sham, and the newspapers were ‘suspiciously wary of crossing him’. By contrast, Cochin was a state that was trying to improve its political culture through the introduction of village panchayats. Its similarly weak administration was not dominated by one personality, its functionaries were more willing to serve, and the government was keen to seek cooperation in tackling its food crisis. These conditions, the Resident felt, were ‘more productive of solid results’.Footnote 132 Travancore’s comparatively repressed environment for free speech and political activity prevented information about the depths of the crisis from being communicated to the British and indeed the rest of the world.

The Resident would note that ‘equally harrowing photographs [to Bengal]’ could be produced from the scarcity areas of Travancore, ‘but feelings of prestige forbid public exposure of the gangrenous sores’ and ‘the criticism is of course feared that the administration is incapable of effecting an equitable distribution of resources’.Footnote 133 The Defence of Travancore Rules allowed Ramaswamy Aiyar to arrest politicians who sought to expose these conditions for sedition. Press communiques warned ‘subversive organisations and movements’ against ‘reprehensible activities and trying to undermine the morale of the people’.Footnote 134 The Travancore police were particularly violent, and the state was known to hire gangs to disrupt meetings held by undesirable elements.Footnote 135

In this environment, there was limited take-up of local knowledge and resources to mobilize more advantaged members of a community towards food relief. When a delegation of communists gathered before Ramaswamy Aiyar to address the food situation in late 1942, they proposed village level food committees to help determine requirements of stock from landholders. The diwan did not engage with them and merely paid lip service to their demands. He further refused to release their existing prisoners and put one member of the delegation in jail. The following year, the government arrested two State Congress members who had vocally advocated village committees as a way to ascertain the excess produce of landholders.Footnote 136 Although the state later released its political prisoners in droves and removed the ban on certain newspapers when it was desperate for help, it issued warnings shortly thereafter ‘against abusing the freedom of speech they have been allowed’.Footnote 137 The lack of a feedback mechanism for the government prevented it from being more proactive. On the other hand, in Cochin, the communists reported being able to convene committees of concerned citizens to prevent profiteering and ensure equitable food distribution.Footnote 138

Cash agriculture had enriched Travancore and enabled the state to make impressive achievements. At the same time, dependence on exports and the lack of self-sufficiency in food left it suffering during the Depression and then in the Second World War. In retrospect, Ramaswamy Aiyar would recognize that he ‘did not have the foresight to advise His Highness that it was all very well to industrialise and to gain money; that money alone is not equivalent to food’.Footnote 139 The unavailability of food, a disempowered bureaucracy devoid of talented personnel, and the absence of a political voice in a highly centralized and autocratic polity combined to unleash a tragedy.

Unequal suffering: Dislocation, disease, and death

In a now-classic essay, Indivar Kamtekar observed that whereas the Second World War created new solidarities in Great Britain, it produced new forms of inequality in India.Footnote 140 Similarly, the effects of Travancore’s management of the shortage varied across class, caste, and space. Some profited. Others starved. Still others moved. Supplementing the archival record with surveys of death and disease rates and novels about food management and migration helps paint a picture of the distinct lived experiences of this tumultuous period in Travancore’s history.

Part VII of Kayar focused on how those poor families with able-bodied sons sent them to enlist in the army and remit money back home. As the war goes on, the local postman brings more news of death in battle rather than money orders. A subsidiary concern of this section of the novel is how those with command of food supplies and other war resources profited handsomely off their supplies while others suffered.Footnote 141 That theme is explored in greater detail in the Indian English-language writer Raja Rao’s (1908–2006) novel, The Cat and Shakespeare: A Tale of Modern India. Drawing upon the author’s experiences living in Travancore’s capital of Trivandrum during the war, the book tells the story of an upright ration clerk battling a corrupt system through the eyes of a witty and cynical colleague.Footnote 142 The narrator Ramakrishna Pai talks about how war allows one to meet the challenge of raising a family on a fixed government salary: ‘Fortunately, there are wars. And rationing is one of the grandest inventions of man. You stamp paper with figures and you feed stomachs on numbers. You know these sadhus (wandering holy ascetics)…For three months, they need no food…I give magical cards, and my wife eats pearl rice. My children go to school.’Footnote 143

In The Cat and Shakespeare, government officers sell false ration cards or sign them for those who are no longer living. Documentation selectively disappears, explained away as having been eaten by rats. Conspicuous consumption and real estate purchases are justified as assets from the wife’s family line. Although fictional, the accounts in the book were inspired by certain real-life events. There was a black market for ration cards to which the poor contributed in order to purchase cheaper substitute foods like tapioca (see below) that would allow subsistence for longer.Footnote 144 And although ultimately the magistrate dismissed the charges, the Travancore government temporarily suspended and investigated the conduct of 116 officers for holding disproportionate assets like large plots of land.Footnote 145 While state-wide procurement and rationing of food curbed black market activity, it was far from a panacea. In some cases, it merely enriched the government servant rather than the trading agent.

For the less fortunate, food scarcity forced uncomfortable decisions that led to displacement, disease, and death, especially in the Shertallai and Ambalappuzha taluks of north coastal Travancore. Thanks to the efforts of the Servindia Relief Centre, a branch of the Servants of India Society (SIS), and its local secretary, K. G. Sivaswamy (??–1957), there is a detailed and rigorous analysis of the effects of the food crisis.Footnote 146 Sivaswamy was a politician who had become a social worker dedicated to improving agrarian India through rural reconstruction and agrarian cooperatives.Footnote 147 He came to Travancore in the second half of 1943 during the brief window of time in which Ramaswamy Aiyar sought cooperation from relief organizations. The four Servindia relief centres across Travancore fed several thousands of children daily and made rigorous studies of the effects of the food shortage in Malabar, Cochin, and Travancore.Footnote 148 The photographic images accompanying these studies capture the extent of the suffering of the people. They have been excluded here to avoid making spectacles of their bodies.Footnote 149

Whereas in the Bengal Famine, the hungry migrated from rural to urban areas in search of food, there was a powerful reverse current of migration out of Travancore. Approximately 12,000 people, mainly smallholding farmers, left for the jungles of Malabar, between 1942–4.Footnote 150 This accelerated a migratory trend from Travancore to Malabar that began in the late 1920s as a consequence of the declining availability of cultivable land.Footnote 151 Migrants were primarily Syrian Christians who often had access to that combination of material resources, skills, and social networks that Joya Chatterji has called ‘mobility capital’.Footnote 152 Having sold their land in Travancore, they attempted to bring mainly tapioca or rice under cultivation, depending on where they migrated to. A key attraction during the war was also a 50 per cent lower controlled price of rice in Malabar than Travancore. If migration to the jungles promised greater food security, it also carried dangers. One of the novels spawned by these wartime migrations, Kuravilangad Joseph’s Dukha Bhoomi (1967), wrote of forests where ‘wild elephants, wild buffaloes, tigers, boars and pythons had freely rambled’. While it promised a life without starvation, this new world required ‘awful hard work, loss of manpower, and many other terrible losses’.Footnote 153 Some migrants failed in their endeavours and were forced to return to Travancore; countless others died of malaria.Footnote 154 Adjusting their diet to the produce of the land led to an overconsumption of carbohydrates and a deficit of fish and coconuts. These settlers suffered from anaemia and scabies. Sivaswamy calculated an excess mortality of 2,000 for this group, or about one in six.Footnote 155

Those who stayed behind experienced more acute under-nutrition and had to eat a greater proportion of substitute foods. Payment in rice for agricultural labour was substituted for paper money that lost its value quickly; the resulting hunger is described movingly in Thakazhi’s 1948 book Rantidangazhi (Two Measures of Rice).Footnote 156 We have already pointed out the small size of the ration; the only thing most people could do with it was prepare rice gruel. Tapioca, which saw an increase in cultivation of about a third during 1943–4 in Travancore, served as the most common emergency substitute food.Footnote 157 Other major dietary substitutes were not always readily accepted. ‘Everywhere, I am met by the appeal for more rice and less bajra, maize, etc,’ the Resident wrote.Footnote 158 It was harder to persuade children to eat substitutes. Too much tapioca retarded their bone growth.Footnote 159 The swelling of their bellies resulted from a condition known as kwashiorkor, caused by inadequate protein in their diets. By far the most common consequences of malnutrition were severe anaemia and oedema. This was a harrowing experience. Swelling begins in the abdomen and spreads through the body, stretching the skin. Blood pressure drops, corneas turn red and sore, and aches and pains develop across the body. A craving for carbohydrates and salt develops, accompanied by uncontrollable diarrhoea. Then, the victims move from depression, to irritation, to unconsciousness.Footnote 160

The young communist E. M. S. Namboodiripad (1909–1998) spoke of how under these circumstances, notions of morality were replaced by survival instincts: ‘Self-respect and fellow-feeling all disappear in the face of hunger. Beg, bribe, borrow, steal, do anything you like so that you may live!—This becomes the desperate mood.’Footnote 161 He reported that thefts had increased. The Resident offered a particularly chilling observation in one of his dispatches, of ‘a huddle of little skinny animals—that were born human’. Protruding ribs, swollen stomachs, and sticklike arms became a common sight. Most tragically, some would never have a real chance to even become fully humans; the average new-born weight declined by eight ounces between March 1943 and September 1944.Footnote 162 Conditions declined as one moved away from urban areas. They were worst in Alleppey and Shertallai.

‘I feel considerable anxiety in view of grave danger of serious loss of life from epidemics following semi-starvation in 1943 and having regard to apparent slow arrival of new supplies,’ wrote the secretary of state for India in early 1944.Footnote 163 These fears were warranted. Rather than outright starvation, it was disease brought on by the reduction in immunity resulting from malnutrition that accounted for most of the increase in deaths from 1942 onwards. Direct casualties from epidemics of smallpox and cholera were roughly 1,000 and 6,605 respectively.Footnote 164 Other conditions that led to death were oedema and dysentery. Sivaswamy estimated the number of casualties from the food crisis between 1942 and 1944 at 89,204 by taking the difference in the average death rate between 1931–41 and the death rate for the individual years, multiplying them by a factor of 1.5 (consistent with the Public Health Department’s estimate of the extent of under-reporting), then multiplying by the population, and summing the totals for the years in question, arriving at a figure of 90,000. Admittedly, this was a crude estimate that did not adjust for changes in the composition of the population and relied on parish records of the CMS, which was active in relief efforts. Nevertheless, Sivaswamy remains the only person to have sought to measure the death toll of this episode.Footnote 165 Excess mortality due to disease continued after the food shortage, meaning that the toll was possibly higher.

Whereas malnutrition was equally distributed in Cochin, Travancore contained greater variation. The worst-affected districts in the north suffered in a manner analogous to their counterparts in Bengal. Things were better nearer to the capital, further south. The food shortage hit the poor especially badly in Travancore. Those who could command excess rations or leave the state did so, by any means possible. Those who could not succumbed to their fate. Even this story, however, is not completely one of disempowerment and death that would later be forgotten. Political developments were underway.

Food, communism, and united Kerala

The food situation created conditions that paved the way for successful wartime communist activity in Travancore, and the end of princely rule. It also helped shape the growing conceptualization of a state of Kerala out of the Malayalam-speaking areas of South India (Cochin, Travancore, and Malabar).Footnote 166 The communists’ internationalist perspective, based on Moscow’s attitude to the war and their localized interest in improving the food situation, assisted them in building a following that could be mobilized to accelerate the end of princely rule and later establish a persistent electoral presence in the region.

The international politics of war led to the separation of communists from the Congress socialists and the end of the United Front. Originally, the communists refused to participate in what they considered an imperialist war. The line changed after Britain and the Soviet Union joined forces against the Axis Powers in 1942. The India’s communists adopted a ‘People’s War’ line and pledged their full support to the British war effort.Footnote 167 The ban on the party was lifted, and the communists refused to participate in the INC’s nationwide Quit India Movement of 1942. As a result, they managed to avoid the arrests and repression that followed and could instead be counted on as contributors to the war effort.Footnote 168

War proved to be a boon for the communists in Travancore. During this time, agrarian labourers formed their first unions, later amalgamating with existing unions as an all-Travancore Trade Union Federation.Footnote 169 Travancore’s own branch of the Kerala Communist Party was founded in 1940.Footnote 170 Unlike the INC, which was dogged by splits between the Congress and the Congress socialists, the communists of Travancore, Cochin, and Malabar stuck together.Footnote 171 Their attitude to the war was, as Namboodiripad remembered, ‘linked with the solution to the day-to-day life problems of workers, peasants and other sections of the common people’. They organized workers and peasants to increase food production, formed feeding centres for the poor, and helped the government get acreage and yield statistics of farms.Footnote 172 Work conducted during 1942–5, especially in Travancore where the INC was prohibited from interfering, helped the idea and slogan of Aikiya Kerala (United Kerala), free of princely or imperial rule and governed by democracy, to take shape.Footnote 173

Coupled with food relief, the communists conducted night classes to educate children and possible party workers in their ideology and train them in guerrilla warfare.Footnote 174 In his memoirs, the communist leader E. K. Nayanar (1919–2004) recalled going under cover in Travancore during the war as a newspaper reporter and conducting secret night classes once he got off work.Footnote 175 Focusing their efforts on factory workers and agricultural labourers, the communists built a support base among the coir workers of Alleppey, where they had led their march from Calicut in 1938. Across the state, by the end of 1945, the communists counted about 45,000 Travancore workers among their ranks. Most were lower caste workers from the Ezhava, Pulaya, and Paraya communities.Footnote 176 A focus on material issues helped them overcome division based on caste.

Writing regular dispatches for the communist newspaper Peoples’ War familiarized Namboodiripad with the food situation enough for him to bring out a short pamphlet in June 1944 called Food in Kerala.Footnote 177 Consistent with the idea of Aikiya Kerala, the pamphlet conceived of Kerala as a unit and explained how the advent of plantation agriculture had created problems of food security. Namboodiripad stressed how the experience of shortage after the fall of Burma was a point of commonality among the less fortunate, an issue around which to cultivate solidarity: ‘Nobody would suffer more from this than the thousands of working-class, agricultural labour, poor-peasant and poor-middle class families who depend on imported rice throughout the year.’ He blamed landlords and traders for hoarding food supplies. More pointedly, he argued that the governments of Travancore, Cochin, and Malabar had failed to understand the importance of social cooperation in bringing together the masses to expose illicit activities and ‘rouse patriotic consciousness’. Restrictions on meetings and activities born out of ‘anxiety to prevent any awakening of political consciousness among the masses’ had precluded bringing in wider support. He targeted the Travancore government’s unwillingness to make use of local food committees which had granular knowledge of specific food requirements and enough social legitimacy to negotiate with traders. Invoking the case of Bengal as a cautionary tale, Namboodiripad suggested that Kerala could avoid the loss of millions of lives through state procurement and rationing, and by abandoning political differences to come together and banish hunger.

In Bengal, and across the country, famine relief and propaganda efforts provided one way for the communists to toe the People’s War line and demonstrate their commitment to the Indian people.Footnote 178 It was one of the factors that helped the party increase its nationwide membership by a factor of four in these years.Footnote 179 The Calcutta communists formed over 100 People’s Protection (Jana Raksha) committees and the all-India Party undertook fundraising activities and marches for famine victims across the country.Footnote 180 Party general secretary, P. C. Joshi, took special pains to raise nationwide awareness of the situation in Bengal among literate and non-literate audiences. Apart from touring the region and writing regularly in People’s War, he found a talented young photographer and new party recruit in Sunil Janah who produced images that soon gained worldwide attention. Joshi recruited playwrights, poets, and visual artists to the party during this time to contribute their talents to publicity work. The Indian People’s Theatre Association toured the country performing plays that raised awareness of the famine; some 60 years later, the historian Bipan Chandra would remember attending a wartime performance of Bhookha Bengal (Hungry Bengal) in Lahore.Footnote 181

The cessation of hostilities would not have been much noticed by the average Travancorean. Food scarcity endured and prices continued to rise.Footnote 182 In Alleppey, the cost of a standard meal rose tenfold between 1939 and 1946.Footnote 183 Syrian Christians persisted in migrating to Malabar, a process that would endure until the 1970s and influence their self-identity as a community of the forward-looking and enterprising. Supplies from the Government of India fell short of promises made.Footnote 184 In the coir industry, reduced demand from the United States after hostilities ended threw a number of workers in that industry out of jobs. The president of the Shertallai Coir Factory Union Workers labelled the ongoing events a ‘man-made famine’.Footnote 185

The communists persisted in tying food-related agitation to ideological concerns. In late July 1946, the Travancore communists raised a jatha (organized march) of 2,000 people, mainly coir workers, shouting food slogans and Inquilab (‘Revolution’) in Alleppey to protest against rising rice prices.Footnote 186 Unlike in Malabar, where the INC had a mass following, in Travancore, communists took the lead in organizing labour strikes, food rallies, and student actions, and in raising demands for a ‘United People’s Democratic Kerala’.Footnote 187

Meanwhile, Ramaswamy Aiyar began to take up the thorny question of Travancore’s political future. Recognizing that the idea of an independent nation-state of Travancore was untenable, he proposed what he called an ‘American model’, of Travancore becoming part of a federation by which it nominally joined an independent Indian Union. Under its terms, there would be universal suffrage along with a permanently ensconced executive. The executive would be appointed by the maharaja. Although the State Congress, which had captured 11 of the 49 seats in the elected assembly, was willing to debate the issue, the communists bitterly opposed Ramaswamy Aiyar’s idea. They raised the famous slogan ‘Throw the American Model in the Arabian Sea!’.Footnote 188

One scholar has referred to the communists’ struggle for popular government in Travancore as ‘the most important chapter in the history of the Communist Party of Kerala’ in the last few years before Indian independence.Footnote 189 These were certainly exciting times. In August, the Communist Party of India authored a resolution calling on party cadres to assert leadership of mass struggles and defeat the INC-style leadership that made compromises.Footnote 190 The government cut food rations and factory owners in Alleppey and Shertallai announced a lockout of workers, putting them out of jobs. Days later, Namboodiripad wrote an article called ‘Travancore Workers on the Brink of War and Starvation and Rule by the Diwan’ in the Malayalam communist newspaper Deshabhimani. By September, labour leaders had been arrested and public meetings banned. A subsequent strike led the Travancore government to promulgate an Emergency Powers Act in October banning strikes, hartals, processions, and labour meetings. It also gave the government the right to confiscate property and imprison those involved in ‘subversive activity’.

In response, the communists planned a general strike for 22 October and organized worker training camps across the state.Footnote 191 The government classified these as insurrectionary. The strike lasted multiple days. On 24 October, a clash between the police and workers broke out, killing two constables, a head constable, and a sub-inspector. The next day, martial law was declared in Shertallai and Alleppey. Ramaswamy Aiyar took over the military which proceeded to raid worker camps. In motor boats, a military detachment approached the peninsular village of Vayalar and opened fire on the more than thousand workers gathered there, killing hundreds. This was the first organized working-class revolt against the government in Indian history.

The Punnapra-Vayalar revolt, as it came to be known, became the stuff of communist lore and attracted public sympathy.Footnote 192 In Kayar, Thakazhi described how it made heroes of its participants and established their political legitimacy:

The leftist candidate was one Sadanandan who had led the Punnapra-Vayalar rising. All his colleagues had fallen dead around him, but he bore a charmed life. The bodies were collected and dumped into a pit which could not contain all of them. So beach sand was piled above the heap of dead bodies and it took the shape of a hillock. It was the torch lighted from that hillock in Vayalar that was taken to every constituency contested by communists.Footnote 193

Food scarcity became a rallying point and material condition that the communists were able to use both to legitimize their cause and win mainly Ezhava and Pulaya converts, thanks to the People’s War line. It enabled them to launch a major uprising and help lay the foundations for their enduring presence in Kerala. Months later, the diwan left his position and Travancore acceded to the Indian Union.

Communism and food policy continued to be closely related in post-colonial India. E. M. S. Namboodiripad, E. K. Nayanar, and A. K. Gopalan, whom we have mentioned at various points in this article, established themselves as stalwarts of the Party. In 1957, the year after Kerala was constituted as a state, its assembly elections brought the world’s first democratic communist government to power. Namboodiripad became chief minister.Footnote 194 Within a year of taking office, the party lifted taxes on foodstuffs and created a two-point policy to bring down the price of rice and meet the food deficit.Footnote 195 As part of this policy, the state took over cultivation in the rice bowl of Kuttanad. Expanding on the idea of wartime food committees the communists had organized, the government directed villages to form People’s Vigilance Committees to advise the authorities on rice distribution. By 1960, its food prices were kept lower than any other state in India, apart from the state of Orissa.

Kerala’s subsequent history has been marked by communist-led governments alternating with INC-led coalitions.Footnote 196 This has helped to produce a distinct model of governance that pays particular attention to health and nutrition. Despite continuing to be a food deficit state, it has the country’s best public distribution system. It operates via a two-level system with a widespread network of ration and fair price shops. Unlike in other areas of Madras presidencies, where these were dismantled after the Second World War, in the areas that became Kerala, they were consolidated and expanded.Footnote 197 The communists have continued to perform well in Alleppey district (which incorporates Alleppey, Ambalappuzha, and Shertallai), where they had been active during the war and helped bring about the Punnapra Vayalar uprising.

Moving beyond Kerala, immediately postwar communist activity gained a greater foothold in Bengal as well. The communist-dominated Kisan Sabha in that region began to organize sharecroppers in a movement to receive two-thirds (or tebhaga) of the land’s produce from the landowners. Recommended by an imperial commission 1940, the measure had been swept under the rug by subsequent events. Restating the demand in a postwar environment on the back of a devastating famine gave it far greater potency. Student communist activists from the cities helped organize villagers across the province in protest, especially in its northern regions.Footnote 198 After the outbreak of state-sanctioned violence against the protestors in early 1947, support for the movement waned. Its spirit lived on, though. As Janam Mukherjee notes, ‘The movement was crushed, but simmered below the surface for decades to come, energizing the Communist Party’s rise to power in West Bengal three decades later. In some sense, the resistance movement generated in the petri dish of famine, had remained coiled at the heart of politics in Bengal all that time.’Footnote 199

Bengal and Kerala would be the two states where communist parties would lead governments in the post-colonial period, and both would be dogged by the tension between class and caste politics. Although that history is beyond the scope of this article, the foundations of their mass following can be traced back to the war years. Unfortunately, Kerala’s turn to parliamentary communism, linguistic statehood, and communist ministry also shifted communist practice towards a more conservative approach focused on the state rather than the people.Footnote 200 The Kerala communists have continued a pattern of upper caste leadership and primarily lower-caste cadres of support, much the same as during the period examined in this article. While many benefits have followed from the state-based approach, it has marginalized the Dalit (formerly known as Untouchable) and adivasi (formerly known as tribal) communities of the state. Kerala’s ‘egalitarian developmentalism’ is therefore predicated on certain kinds of treatment by the state that does not acknowledge differences of disadvantage across communities.Footnote 201 In social life, caste endogamy and caste-based residential segregation endure, even if the more venal practices of earlier times have disappeared.Footnote 202 To use Marx’s terms, ‘political emancipation’ has not led to ‘human emancipation’.Footnote 203

Conclusion

In 2018, the Malayalam film Bhayanagam (Fear) was released to much critical acclaim.Footnote 204 Adapted from Part VII of Kayar, the film explores the fate of Kuttanad soldiers who join the war effort to support their families through the figure of a nameless postman delivering letters and money orders to family members. The postman becomes a bad omen; as the war progresses, the letters he brings tell increasingly of the death of these soldiers and brings grief to their families. The death of Travancore soldiers outside their home soil—forced to embrace an alien cause thanks to their poverty—and the profound agony this evokes, are the primary concerns of this film. With the exception of one scene in which a smug, heartless landowner tells the labourers gathered outside his home to get food from the ration shop instead of ogling his granary, the ‘cry of distress’ emanating from within Travancore is left out. The film’s antiwar, anti-imperial objective leads to its omission of the less sensational, slower, but equally substantial loss of lives at home.

Cash agriculture compromised Travancore’s food independence and left its inhabitants at the mercy of a belatedly conceived and leaky procurement and rationing apparatus during the war. However, these trends, combined with a strong culture of literacy and education, also fomented the rise of class politics and brought food to the centre of the Communist Party’s platform, with enduring consequences. Understanding the unique history of the princely state is crucial to understanding the consequences of food scarcity and suffering. It is necessary for deciphering the post-colonial political trajectory of Kerala.