Introduction

Scholarship on procedural justice has explored and contested the principles that treating people fairly in the resolution of disputes is both an important end in itself as well as a way to support a person's sense of the legitimacy of a decision. That literature has examined the application of the tenets of procedural justice in several contexts, including the workplace (Reference MarshallMarshall, 2005), the actions of Ombuds offices (Reference Creutzfeldt and BradfordCreutzfeldt & Bradford, 2016), and interaction with the police (Reference Hough, Jackson, Bradford, Tankebe and LieblingHough et al., 2013; Reference TylerTyler, 2017). Though growing (Reference Calavita and JennessCalavita & Jenness, 2015; Reference Dâmboeanu, Pricopie and ThiemannDâmboeanu et al., 2021), less attention has been given to the setting of incarceration. Yet, as Reference Calavita and JennessCalavita and Jenness (2015) remind us, prisons present a special context involving a complex interplay between security considerations and the promotion of dignity. Prisons are places of “pains” (Reference SykesSykes, 1958), which can be exacerbated by the decisions of the prison authorities which may impact greatly on a person's everyday life.

Grievance or complaints procedures may play a role for incarcerated people to respond to these pains. However, as the foundational work of Reference Calavita and JennessCalavita and Jenness (2015) found, grievance procedures are subject to complex and often contradictory views among incarcerated populations. Reference Jenness and CalavitaJenness and Calavita (2018) argue that “context matters” when understanding the operation of procedural justice, and that imprisonment may spur on the use of formal complaints systems despite the many barriers to doing so. Part of this context is what Reference SextonSexton (2015) describes as “penal consciousness,” a term used to describe the ways in which people in prison experience and conceptualize laws, rules, and other aspects of prison life. Views of complaint procedures warrant analysis for the ways they shape, and are shaped by penal consciousness. How these interaction works have much to tell us about the operation of procedural justice and legal consciousness in the emerging domain examining the setting of incarceration. Incarceration is a context where rights are inherently limited, and understanding how dispute-resolution operates there has much to offer fresh understandings of these classic concepts.

While scholarship on complaints-making in prisons is only emerging, a wide array of domestic law and international human rights norms exhort states to set up or maintain fair and accessible processes for resolving complaints. Complaint procedures are required by the United Nations' Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Mandela Rules, 2015) and the Council of Europe's European Prison Rules (2019), with the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) also stating that complaint procedures are “an important safeguard for the prevention of violations resulting from inadequate conditions of detention” (Ananyev and ors. v. Russia, 2012). Though domestic and international law suggests that complaints procedures can play an important role in protecting the rights of people in prison, scholarship suggests that this faith is rather misplaced. There is well-developed US literature which casts doubt on the ability of grievance procedures to provide a meaningful experience of procedural justice or rights-protection to people in prisons (Reference Bordt and MushenoBordt & Musheno, 1988; Reference EdelmanEdelman, 2016), with critique of complaints systems found in many other contexts including Romania and Ireland (Reference Dâmboeanu, Pricopie and ThiemannDâmboeanu et al., 2021; Inspector of Prisons, 2016).

In this study, we examine how people in prison perceive and use a complaints mechanism, through analysis of findings from a self-administered survey conducted with people serving sentences in three prisonsFootnote * in Ireland. This survey explored people in prison's perceptions and usage of the complaints system, as well as their recommendations for improving it. We assess the complex interplay between a person's perceptions of rights and their views of the complaint procedure, as well as the factors associated with usage and views of the mechanism. Studies of complaints-making in prisons remain rare (Reference Calavita and JennessCalavita & Jenness, 2015; Reference Dâmboeanu, Pricopie and ThiemannDâmboeanu et al., 2021), and we add the first study on this subject from Ireland. In doing so, we contribute to the broader literatures on procedural justice, legal consciousness and legal mobilization by offering both a perspective from prison and from Ireland. We examine who complains and what factors are associated with complaining and views of complaining in the very particular socio-structural context of incarceration. Incarcerated people are wholly dependent on state authorities for the basic necessities of life, access to services, and contact with their families. Those who are the likely subject of complaints: prison staff or managers are very often in daily contact with people in prison and can play a decisive role in one's experience of punishment. Complaining about decisions or treatment therefore may be subject to subtle and unsubtle repercussions which do not exist to the same degree in the nonincarcerated world and understanding the extent of formal complaints and factors influencing usage and views can shed light on how dispute-making works under such constraints. Second, those who are incarcerated often come from backgrounds characterized by marginalization and disenfranchisement, recognized as core barriers to taking action against state bodies or powerful groups (Reference BehanBehan, 2014). As such, understanding the extent to which people make complaints while incarcerated, and exploring some of the factors associated with complaining and views of complaints structures have much to offer wider debates on legal mobilization.

We believe that the experience of Ireland further offers some valuable lessons for a wider audience. First, there is a need for greater geographic diversity in examinations of procedural justice and complaints procedures in prisons, which have tended to focus on the US. More generally, the issue of complaining in prison has been subject to relatively little examination either in the US or outside of it, with few examples of such analysis (Reference Calavita and JennessCalavita & Jenness, 2015; Reference Dâmboeanu, Pricopie and ThiemannDâmboeanu et al., 2021). This lack of research is concerning, given the belief evident in international human rights standards that complaints procedures can support the prevention of ill-treatment in the prison setting. Whether this objective is, in fact, being met in the lived experience of people in prison needs close analysis. We also believe that studies from outside the US have a particular usefulness. In a key point of contrast to the Prison Law Reform Act, 1995, Ireland does not require a person in prison to file a complaint before taking a legal action concerning detention. This requirement has come in for some particularly strong criticism in the US (Reference Schlanger and ShaySchlanger & Shay, 2008). As a context in which complaining is not tied in statute to judicial review, the Irish experience allows us to take the first steps in assessing whether there are differences in experience when such conditions are not applied.Footnote †

Procedural Justice and Legal Consciousness in the Context of Incarceration

Understanding the making of complaints by people in prisons draws together several strands of literature, including that on procedural justice, legal consciousness, and legal mobilization, as well as penal culture. Procedural justice literature has grown considerably since the essential studies of Reference Thibaut and WalkerThibaut and Walker (1975), and Reference TylerTyler (1984). There has been a burgeoning scholarship concerning procedural justice in the context of policing (Reference Tyler and JacksonTyler & Jackson, 2013), which has identified two central components which influence a person's view on whether an encounter was procedurally just: fairness of treatment, and fairness of decision-making (Reference Tyler, Fagan and GellerTyler et al., 2014). Several critiques have been made of such work, particularly concerning its application to real-world contexts (Reference Hayden and AndersonHayden & Anderson, 1979), including prison (Reference Jenness and CalavitaJenness & Calavita, 2018). Reference Jenness and CalavitaJenness and Calavita (2018) have argued that procedural justice theory breaks down in the context of incarceration. They noted that in high stakes and highly hierarchical environments involving deeply embedded power imbalances and historical disadvantage, outcomes matter a great deal (Reference Calavita and JennessCalavita & Jenness, 2018).

While a person's perceptions of dispute resolution may be influenced by their experience of the process, the outcome is also deeply connected to the concept of legal consciousness (Reference CowanCowan, 2004; Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick & Silbey, 1998; Reference MarshallMarshall, 2005), and, as legal mobilization theory shows, to the factors which impel or inhibit a person to even name something as a dispute (Reference Felstiner, Abel and SaratFelstiner et al., 1980), or to act upon a feeling of injury (Reference BumillerBumiller, 1987). Across this work, we see that the processes of considering something to be first, a wrong, second, caused by a blameworthy other, and third, something to act upon, are all situated within social, cultural, and psychological contexts. Some may fear retaliation (Reference BumillerBumiller, 1987), others lack the cultural power necessary to use ostensibly accessible grievance procedures (Reference MarshallMarshall, 2005); self-blame may also be an inhibiting force (Reference MichelsonMichelson, 2007). At the same time, people who are at the margins of society may also use the law to fight back (Reference CowanCowan, 2004) and to assert their identity, or their claims.

Incarceration is a very particular context for the expression of rights and for the resolution of disputes. Recognizing this, Reference SextonSexton (2015) has developed the valuable concept of “penal consciousness” to describe the multitude of factors, pre- and during imprisonment, which shape how a person experiences their time in prison. Drawing on this insight, we might add that a person's perceptions of complaints-making is intimately connected with their pre-prison lives and their experiences therein. Reference Calavita and JennessCalavita and Jenness (2015, Reference Calavita and Jenness2018) have unraveled many of these connections through their study of grievance procedures in Californian prisons. These authors have found extensive use of the grievance procedure despite the myriad factors which may have inhibited such actions, including marginalization, the hierarchical structure of prison, and the fear of retaliation. They attribute this, in part, to the “hyperlegal” (Reference Calavita and JennessCalavita & Jenness, 2015, p. 76) nature of prisons, where people feel that where rules are broken that negatively affect them, that breach must be remedied in some way, pushing that problem up the “pyramid of disputes” (Reference Felstiner, Abel and SaratFelstiner et al., 1980). This hypervisibility trumps the social and psychological factors that, in other populations, might dampen the likelihood of “claims-making.” Incarcerated people also felt strongly that they could use the prison's own rules in an effort to hold officers into account, arguing “that if they have to abide by the myriad of rules and regulations that apply to them, staff should comply with their departmental policies too” (Reference Calavita and JennessCalavita & Jenness, 2015: 72). This perspective resonates with the concept of “censoriousness” described by Reference MathiesenMathiesen (1965), whereby people seek to fight back against injustices they experience using the tools of their incarceration.

A lack of faith among incarcerated people in bodies set up to deal with their grievances has been found in other research. As part of an extensive ethnographic study of an English prison, Reference CreweCrewe (2012) found a significant lack of trust among people in prisons concerning Visiting Committees. These bodies—now known as Independent Monitoring Boards—have the remit to meet people in prisons and seek to resolve any issues brought to them informally. Similarly, the people in prisons in Reference Martin and GodfreyMartin and Godfrey's (1994) study in England and Wales felt that the Boards were invisible, irrelevant, and aligned with prison management. Reference Edgar, O'Donnell, Martin and MartinEdgar et al. (2003), in a mixed methods study in England, found that participants felt very let down when no action was taken in response to complaints. The effects of these feelings can be serious. Studies have found a link between perceptions and experiences of procedural justice and prison violence and likelihood of reimprisonment, with Reference Beijersbergen, Dirkzwager and NieuwbeertaBeijersbergen et al. (2016) finding that people in prisons who felt that they were treated fairly and respectfully by correctional authorities were less likely to be reconvicted up to 18 months after release. Reference BierieBierie (2013), using data over a seven-year period from 114 federal prisons in the US, found that violence within a prison increases significantly with the volume of late replies to complaints, as well as substantive rejections of complaints.

Outside of the work of Calavita and Jenness, the question of procedural justice in the prison context has tended to focus on relationships between staff and people in prisons, with the related concept of legitimacy becoming a key consideration in studies of penal power (Reference Jackson, Tyler, Bradford, Taylor and ShinerJackson et al., 2010; Reference Sparks and BottomsSparks & Bottoms, 1995), as well as an important value to measure in understanding the moral performance of a prison (Reference Liebling and ArnoldLiebling & Arnold, 2004). These studies offer additional insights for how to understand perceptions and usage of complaints. It is clear, for example, that relationships play an important role in prison as incarcerated people are heavily reliant on staff in accessing their fundamental rights (Reference Crewe, Liebling and HulleyCrewe et al., 2015; Reference Liebling and ArnoldLiebling & Arnold, 2004; Reference Menés, Jorge and FerrándezMenés et al., 2018). Reference Hulley, Liebling and CreweHulley et al. (2012), in their examination of what “respect” means in the prison context, found that it did not always mean receiving a favorable response to a request, but one which was fair and unambiguous and removed people in prisons from a state of uncertainty. Reference Bottoms and TankebeBottoms and Tankebe (2012) also note the connections between outcome and procedural fairness and the legitimacy of staff in the eyes of the people in prison. Moreover, prisons have been found to be low-trust environments (Reference Crewe and BennettCrewe & Bennett, 2012; Reference Liebling and ArnoldLiebling & Arnold, 2004), a feature which can be compounded by pre-existing relationships with authorities.

Very few studies have explored the backgrounds of those who are more likely to complain. Reference Morgan, Liebling, Morgan, Maguire and ReinerMorgan and Liebling (2007) have, however, found that those serving long sentences in conditions of high security were more likely to bring complaints to an Ombudsman which could hear complaints from people in prisons, than their short-term, low-security counterparts. As noted by participants in a qualitative study conducted in Australia, significant delays in responses to complaints can impact upon short term people in prisons, who may view it as unlikely that they will receive a response before the end of their sentence, and therefore feel apathy about making a complaint (Reference NaylorNaylor, 2014). Reference Dâmboeanu, Pricopie and ThiemannDâmboeanu et al. (2021) examined the context of complaints in Romania, using a wide definition of complaint from an action internal to the prison to legal action domestically or to the ECtHR. They found that those who had served longer periods in prison were more likely to have made a complaint, citing delay as one potential reason. People in maximum security institutions and closed regimes were also more likely to complain, as were those who had interacted with NGOs. Race has also been explored (Reference Calavita and JennessCalavita & Jenness, 2018). These authors found an absence of race effects on views, with people in prisons' satisfaction with the grievances, their outcomes, and perceived fairness not varying significantly across races.

Grievances and Complaints in Prison in Law

Having effective and trustworthy systems for resolving complaints and grievances by people in prisons is recommended by human rights bodies, and one long recognized (ICRC, 1958). A right for people deprived of their liberty to complain is found in the Geneva Conventions (Article 78 Geneva Convention III). The original Mandela Rules of 1955 also contain a right to make a complaint (Rule 35 United Nations Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders, 1955). These instruments frame the administration of complaints procedures as a way to prevent human rights violations and to combat impunity among those responsible for ill-treatment. Understanding the experience of those who can use them is needed to assess if that experience measures up to the intended goals of these instruments. In addition, a key objective of the present study was to examine what people in prison thought makes for a good complaint mechanism. International human rights standards on complaints in prisons will now be explored.

The Mandela Rules and the European Prison Rules

Both the United Nations Mandela Rules and the Council of Europe's European prison rules (EPR) require states to provide people in prisons with access to complaint mechanisms (Rule 56 Mandela Rules; Rule 70.1 EPR). Both require people in prisons to receive information on how to make requests or complaints (Rule 54[b], Rule 55 Mandela Rules; Rule 70.4 EPR), in a way that the person can understand. Rule 57.1 states that complaints must be dealt with promptly and replied to “without delay” (Mandela Rules 2015). States must also provide an opportunity for appeal or review of a decision on a complaint (Rule 56 Mandela Rules; Rule 70.1 EPR).

The EPR further require that all complaints shall be dealt with as soon as possible, using a process that “ensures, to the maximum possible extent, the people in prisons’ effective participation” (Rule 70.5). Providing reasons for rejecting a complaint is a specific requirement. Confidentiality should also be offered to the people in prison (Rule 70.8), while Rule 70.5 also states that people in prisons shall not be “exposed to any sanction, retaliation, intimidation, reprisals or other negative consequences” due to having submitted a complaint.

The European Court of Human Rights and the Supreme Court of the United States

The European Court on Human Rights has also considered the role of people in prison complaints systems in a number of cases concerning the right to an effective remedy under Article 13 of the European Convention on Human Rights. While no specific model is required, a series of cases has established key principles which complaint procedures, on their own or combined with other forms of redress, must comply. They must:

a. be independent of the authorities in charge of the penitentiary system or have the possibility of an independent appeal (Domjan, 2017; Silver, 1983; Varga, 2015);

b. secure the people in prisons' effective participation (Ananyev, 2012; Neshkov, 2015; Varga, 2015);

c. ensure the speedy and diligent handling of complaints (Ananyev, 2012; Domjan, 2017; Neshkov, 2015);

d. have a wide range of legal tools for eradicating the problems that underlie complaints (Ananyev, 2012; Rodic, 2008); and

e. be capable of rendering binding and enforceable decisions, and any relief must be capable of being granted in reasonably short time limits (Neshkov, 2015; Silver, 1983; Varga, 2015).

The US Supreme Court has also stated its view that remedies must be truly available to a prisoner to be considered a remedy under the Constitution. In Ross v. Blake (2016, p. 9) the Supreme Court interpreted the term “available” in a pragmatic way. A remedy may not be available where, for example, officers are unable or consistently unwilling to provide relief, or decline ever to exercise their authority in favor of the people in prison, or because it is opaque and confusing, or because the prison administration deploy misrepresentation or intimidation to prevent its use.

Overview of Irish Prisons and Complaint Procedures

The Irish penal context and people in prison complaint procedures

Ireland has a prison population at the mid-range of European prison systems, at 84 per 100,000 inhabitants (World Prison Brief, 2020). Ireland has 12 prisons, including two prisons for women and two open prisons. There is no formal security categorization applicable, with people in prisons from a variety of demographic and offense backgrounds housed in the same prison.

The current prison complaints system, which is the subject of study, was introduced in policy in 2014 (Irish Prison Service, 2014). New secondary legislation in the form of the Prison Rules (Amendment) 2013 (S.I. No. 11 of 2013) created procedures in law for certain types of complaints, involving allegations of assault, the use of excessive force, racism, and other similar issues. The subsequent policy document from the Irish Prison Service (2014) created to implement this law in practice created additional categories of complaints, which are characterized as ranging from A to F depending on the seriousness of subject matter of the complaints. The complaint system is governed by the Prison Rules (Amendment) 2013 in the case of Category A complaints (allegations of assault or use of excessive force, ill-treatment, racial abuse, discrimination, or similar conduct) and an internal Irish Prison Service (IPS) policy for other categories, which governs all other types of complaints. The IPS Policy Document on the Complaint Procedure, however, has no formal legal authority. Prior to 2013, complaints were governed by the Prison Rules, 1947 (S.I. No 320 of 1947), which simply permitted complaints or requests to be made to the governor or director of the prison, and the Prison (Visiting Committees) Act 1925, which allowed people in prison to make complaints to external bodies appointed by the Minister for Justice, but with no power to resolve the matter. Prior to 2014 there was no formal protocol for how complaints were to be made.

Under the 2014 policy, complaints are made by people in prisons using a specifically designed form for this purpose (available in Appendix A in Data S1). This form is then to be placed in a designated complaint form box found on prison landings. IPS policy provides that complaint boxes be provided and emptied on each working day, that all complaints are logged and assigned a reference number and are photocopied and returned in a sealed envelope to the people in prison (Irish Prison Service, 2014). The procedure which must be followed differs according to the categorization of the complaint. In the case of Category A complaints, independent investigators are appointed to investigate the complaint, but the final decision on its outcome remains with the Irish Prison Service (Prison Rules (Amendment) 2013 S.I. No. 11/2013). For other types of complaints, the investigation and decision-making are entirely internal to the prison system, and the timelines for resolution laid down in the policy document range from 48 h (Category C) to 28 days (Category B), though these can be extended. No upper time limits apply to Category A complaints.

Once a complaint has been investigated, under the policy the outcome of the complaint must be communicated to the people in prison. In the case of a Category A complaint, the prison governor (warden or prison director) may find the following on the basis of the report of the external investigators:

a. there are reasonable grounds for sustaining the complaint;

b. there are no reasonable grounds for sustaining the complaint;

c. it has not been possible to make a determination.

The governor may (rather than must) state the reasons for his or her finding. The governor also decides what action should be taken and there is no provision for the decision to be appealed to an external body. In the case of other complaint categories, the same possible findings are available, but in the case of an appeal to the prison governor, the governor can uphold the initial finding, quash it, or order a fresh investigation. Again, no provision for an external appeal applies.

The Irish complaint procedure in practice

There are limited data available on the use of the complaints system and its outcomes, because official figures are not published. The only published study of the Irish complaints system was carried out by the Inspector of Prisons, a body which visits prisons and writes reports on the treatment and conditions therein, and which has a general oversight role of the complaints system under the Irish Prison Rules (S.I. No. 252/2017). The inspector carried out a review of six prisons over a period of six months from July 2014 to January 2015, examining Category A to Category D complaints. The inspector found that, during that period, 556 complaints had been lodged across those prisons, with two-thirds of complaints categorized as Category C (i.e., service-level) complaints. More recent data obtained by Irish Penal Reform Trust shows that, in 2018, only 5% of Category A complaints were upheld, in contrast to 31% of all other categories of complaints. The average length of time to investigate a Category A complaint (January 2018–June 2019) was 2.5 months, while it was 1.5 months for other categories of complaints (Irish Penal Reform Trust, 2019).

The complaints system has been strongly criticized by the Inspector of Prisons for its delay, lack of responses to people in prisons, and the absence of an independent appeals mechanism. A lack of powers of enforcement regarding the outcome of complaints, as well as failures to adhere to protocols and poor record-keeping came in for critique (Inspector of Prisons, 2016). Reports by the European prison monitoring body the Committee for the Prevention of Torture (CPT) and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment also expressed concerns about poor recording of complaints by people in prisons and advocated for the establishment of an independent complaint mechanism (Council of Europe, 2006, 2017). A decision by the High Court of Ireland has described the complaint system as “failed,” with people in prison's lack of confidence in it being “objectively justifiable” McD v Governor of X Prison (2018; para 132), on the basis of poor adherence to timelines, unreasonable findings by staff, and a significant lack of resources to run the complaints system.

In light of the Inspector of Prisons' report and criticisms from other bodies, the complaint system is currently being reviewed. Key changes being proposed are the simplification of the procedure to two categories down from the current six. Furthermore, the general Ombudsman's office, which deals with a variety of public bodies, is being considered as an independent review mechanism for the current system (Inspector of Prisons, 2016).

Current Study

Through the work of Reference Calavita and JennessCalavita and Jenness (2015) and Reference Jenness and CalavitaJenness and Calavita (2018), procedural justice and legal consciousness scholarship has begun to penetrate prison walls. However, literature on people in prisons' complaints from contexts outside California remains scarce (Reference Dâmboeanu, Pricopie and ThiemannDâmboeanu et al., 2021). Research on prison life, penal experiences, and the legitimacy of penal regimes has also increased greatly in recent years, but the relationship between complaints-making in particular and oversight in general with aspects of penal consciousness (Reference SextonSexton, 2015) has yet to be explored. The current study contributes to filling these gaps by examining complaint usage and perceptions in a jurisdiction which does not have the same fraught history as the US in the arena of people in prisons' grievances and where people in prison do not yet have to exhaust the internal complaints procedure to litigate. The experience of Ireland can also offer valuable insights for other countries seeking to reform their prison complaints mechanisms. In addition, there remains a lack of quantitative studies examining correlates of complaint usage and perceptions using larger samples of people in prisons, with much of the insights on this topic coming from, albeit very valuable, qualitative research. In this way, we seek to make a wider contribution to the literature and policy in this area. This research has three aims: (1) to explore complaint usage and factors associated with it, (2) to analyze perceptions of the complaint system and its correlates, and (3) to examine the attributes of a good complaint system, from the perspective of people in prisons. Given the lack of existing data and the exploratory nature of the study, research questions are preferred over specific hypotheses.

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants were 508 incarcerated males, randomly selected from three medium-security prisons in Ireland.Footnote ‡ To be eligible for the study, residents had to (1) be serving a sentence, (2) be imprisoned for more than one month (to avoid the early, vulnerable stage of imprisonment, and have an opportunity to gain knowledge and experience of the system), and (3) be fluent in English (the language of the survey materials). The sampling frame was a list of eligible participants generated by the prison on the first day of fieldwork. Each participant was assigned a number, and a random list of numbers was selected using simple random sampling. Data were collected between November 14, 2018, and February 18, 2019, after receiving approval from the University Ethics Committee and the Irish Prison Service. Participants were provided with a three-page self-administered paper-and-pencil survey, a consent form, and an envelope. The first author delivered the materials to the residents and collected them later. A small number of participants (n = 4) completed the survey with the assistance of the first author due to literacy difficulties. To increase awareness of the study, posters were placed throughout the prisons advertising the study during data collection. No incentives were offered for participation. Of the 616 people invited to participate, 517 agreed, resulting in an overall response rate of 83.9% (ranging from 79.5% to 88.0% across prisons). After excluding nine participants with missing information on most variables, the analytic sample comprised 508 people.

Instrument and measures

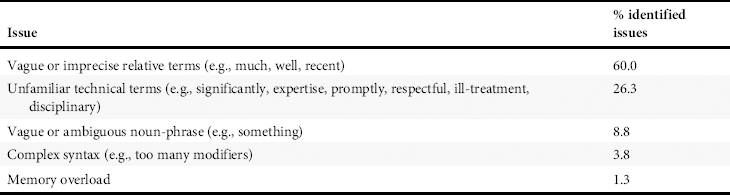

The information was collected using self-administered paper-and-pencil surveys. The questionnaire was designed by the authors and pretested using a sequential design. The first stage of the pretest process included an analysis using the QUAID tool, a Web application specifically designed to identify wording problems in survey questions and answers (Reference Graesser, Cai, Louwerse and DanielGraesser et al., 2006). The problems identified by QUAID (unfamiliar technical terms, vague or imprecise terms, vague or ambiguous phrases, complex syntax, and working memory overload, see Table 1) were examined, and the questions were modified. The updated questionnaire was then evaluated by four experts, using a standardized evaluation form designed by the authors. The reviewers were selected based on their training and experience and their feedback was incorporated into the questionnaire. Finally, the revised questionnaire was administered to a small group of current (n = 4) and former (n = 4) incarcerated people and respondent debriefing questions were used to examine interpretations of questions and instructions (the questions used during the sessions can be found in Appendix B in Data S1).

Table 1. Issues identified by the QUAID software during the pretest

Note: Percentages do not add up to exactly 100% due to rounding.

Perceptions and usage of the complaint system

The primary goal of this study was to examine perceptions and usage of the complaint system. First, five items, measured on five-point scales, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree, were used to create an index of satisfaction with the complaint system, in which high scores represented more positive views. Example items include “the complaint system works” and “using the complaint system gives me a voice in prison.” All five items loaded on a single factor (factor loadings >0.45) and the internal consistency of the scale was satisfactory (α = 0.80). The total score was computed by averaging the values of the five items comprising the scale (after reverse-coding one item formulated in the opposite direction). The wording of all the questions used in the analysis is available in Appendix C in Data S1.

Usage of the complaint system was measured through a binary question that asked respondents whether they had used the complaint system in the prison where they were incarcerated. Two additional variables related to the way in which the complaint system is perceived were included in the analyses: outcome-idealism and preeminence of complaints' outcomes. To measure the former, respondents were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement “prisoners who complain get what they want in prison.” Response options ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater belief in satisfactory outcomes. Preeminence of complaints' outcomes was measured by asking respondents whether they agreed or disagreed with the following statement: “When making a complaint, it is the outcome that matters not the process.” Response options ranged from 1 to 5, with higher scores suggesting a preference for the outcome, rather than the process.

Variables related to prison life

To explore whether perceptions and usage of the complaint system is related to prison life and climate (aspects of legal or penal consciousness), three variables were included in the analyses: sense of safety, respect for rights, and confidence in prison staff. Sense of safety was measured using a three-item scale that asked respondents about their perceived safety in prison (e.g., “I feel safe from other prisoners”). These items were measured on five-point scales, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). They were combined into a single scale, in which higher scores indicated greater perceived safety. These three items loaded on a single factor, with loadings ranging from 0.58 to 0.93 (α = 0.82). Respect for rights was queried by means of three questions asking respondents the extent to which rights are respected in prison, they feel informed about their rights, and able to assert them. These items were measured on scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). An exploratory factor analysis revealed that all three items loaded on a single factor (factor loadings >0.65), with the resulting scale having strong internal consistency (α = 0.82). Responses were averaged to create this index, on which higher scores indicated a strong respect for rights. Confidence in prison staff was measured by asking respondents whether they agreed or disagreed with eight statements (e.g., “If I have an issue, I can talk to staff about it”). Responses to these items were averaged to produce a scale, on which higher scores indicated greater confidence in prison staff (factor loadings >0.55; α = 0.92).

Sentence-related variables

Four sentence related variables were included in the multivariable models: prison where respondents were based (1, 2, or 3), sentence length (less than 1 year, 1 to less than 5 years, 5 to less than 10 years, and 10 years and over), level of privilegesFootnote § (basic, standard, enhanced), and protection statusFootnote ¶ (yes–no).

Background characteristics

A number of demographic variables were used in the analyses. These included age (in years), nationality (distinguishing between Irish and non-Irish residents), education level (no formal education, primary education, lower secondary education, upper secondary education, and college education), and whether respondents belonged to a discriminated group (yes-no).

Analytical strategy

Descriptive statistics were computed to examine the characteristics of the sample and their perceptions and usage of the complaint system. To explore correlates of complaint usage, a logistic regression model was estimated. Then, an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model was used to analyze the associations between satisfaction with the complaint system, complaint usage, and penitentiary variables while controlling for background characteristics. Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) suggested no multicollinearity issues in any of the models (ranging from 1.1 to 2.6). Despite the hierarchical structure of the data (residents —Level 1—within prisons—Level 2—), given the low number of Level 2 units (n = 3), fixed effect models were preferred over random effect ones (Reference McNeish and KelleyMcNeish & Kelley, 2018). The percentage of cases with missing values ranged from 0% to 22.64% (M = 8.25%, SD = 6.83%). Missing data were handled using multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE), creating 20 data sets that were used to estimate the multivariate models.

Results

Description of the sample

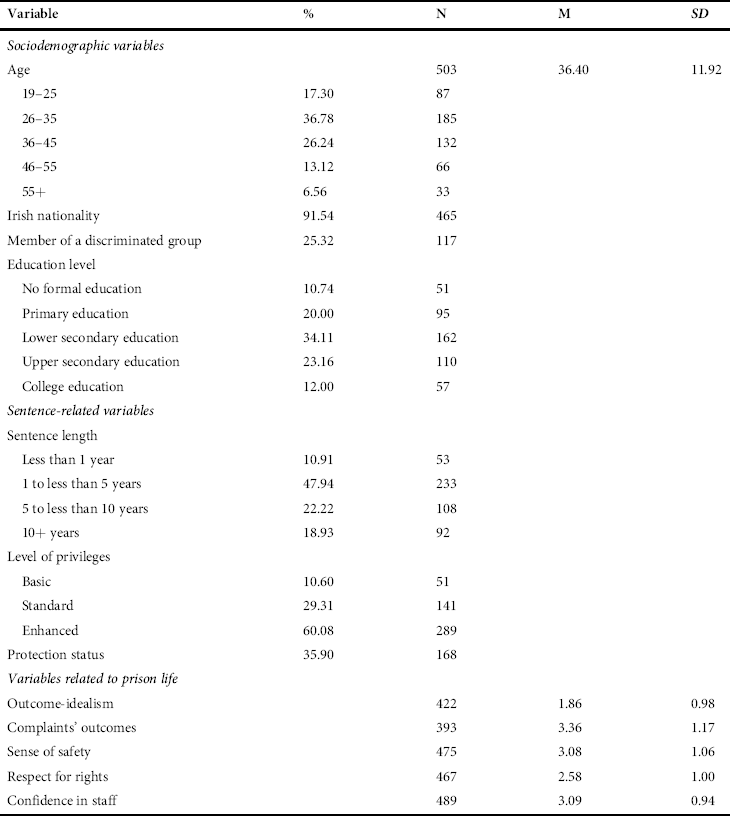

Summary statistics for all covariates are presented in Table 2. The youngest respondent was 19 and the oldest 80 years old, with an average of 36.40 (SD = 11.92). The sample was predominantly Irish (91.54%), and roughly one in four indicated belonging to a discriminated group (25.32%). Approximately one-third of the respondents had lower secondary education (34.11%) and nearly half of the people in prisons were serving sentences of 1 to 5 years (47.94%). Slightly over one in three (35.90%) were on protection, separated from the general prison population, and the most frequent level of privileges was “enhanced” (60.08%), which refers to the status of the people in prisons in the IPS' incentivized regime category based on behavior, which offers the highest level of privileges.

Table 2. Sample characteristics

Abbreviations: M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

On average, respondents scored 1.86 (SD = 0.98) on the scale measuring outcome-idealism (range 1–5), revealing a lack of belief that people in prisons receive what they want when they complain. In addition, they considered the outcome to be slightly more important than the process (M = 3.36, SD = 1.17). The average score on the respect for rights index fell in the lower half of the scale (M = 2.58 on a scale from 1 to 5), suggesting certain feelings of right violations. Finally, perceived safety and confidence in staff scores fell approximately in the middle of the scales, indicating neutral views.

Complaint usage

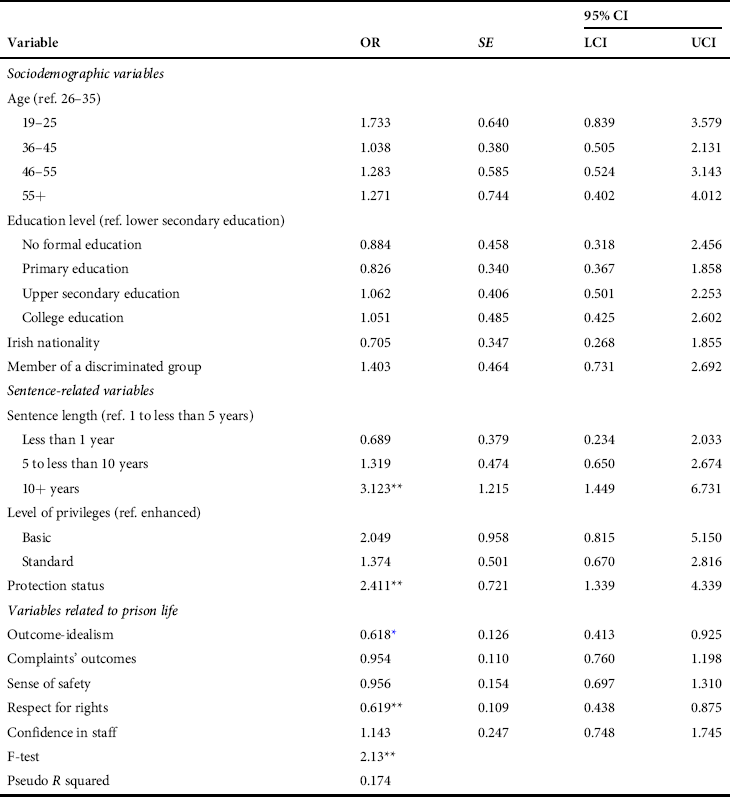

Slightly over one in five respondents (22.41%, 95% CI = 0.18, 0.27) reported having used the complaint system in the prison where they were housed at the time of data collection. To examine correlates of complaint usage, a fixed-effects logistic regression model was estimated. The results of this model, including the odds ratios (OR), standard errors (SE), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), are presented in Table 3. Sentence length was associated with complaint usage, and people in prisons serving sentences of 10 years or more were more likely to have complained (OR = 3.12, 95% CI = 1.45, 6.73, p = 0.004) than those serving sentences of 1 to less than 5 years. In addition, those on protection were more likely to report having used the complaint system (OR = 2.41, 95% CI = 1.34, 4.34, p = 0.004). In contrast, a greater sense that rights are respected in prison was associated with a decrease in the odds of complaint usage (OR = 0.62, 95% CI = 0.44, 0.88, p = 0.007). Similarly, outcome-idealism was associated with complaint usage, and residents who had used the complaint system were less likely to agree with the statement that “prisoners who complain get what they want in prison” (OR = 0.62, 95% CI = 0.41, 0.93, p = 0.020).

Table 3. Fixed-effects logistic regression model predicting complaint usage (n = 508)

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; LCI, lower confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SE, standard errors; UCI, upper confidence interval.

*p ≤0.05, **p ≤0.01.

Perceptions of the complaint system

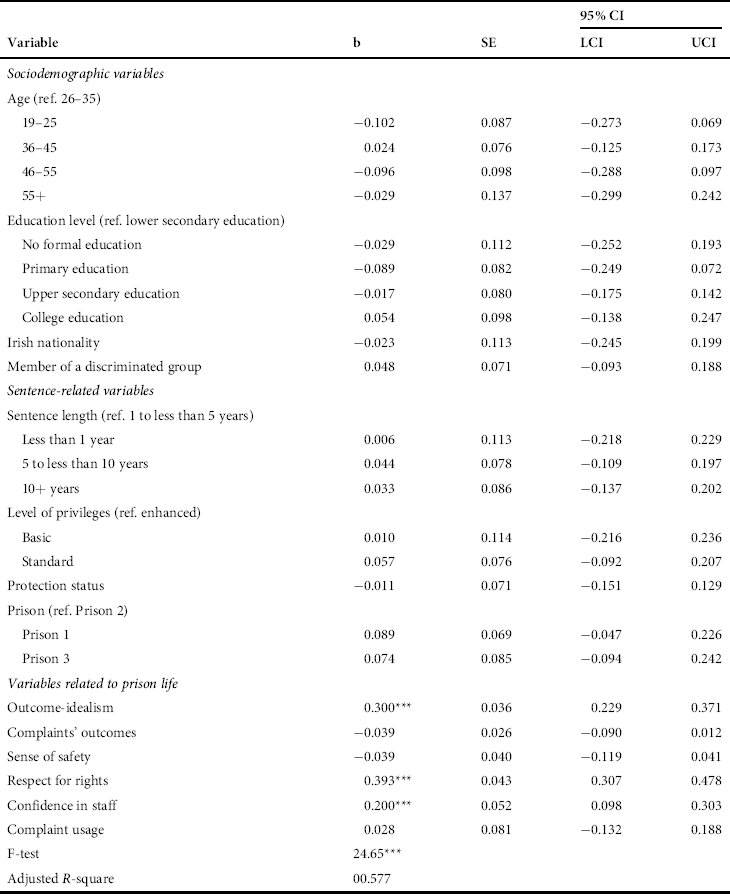

On a scale from 1 (lowest) to 5 (highest), the mean value for the index of satisfaction with the complaint system was 2.41 (95% CI = 2.33, 2.50), indicating that satisfaction was generally low. A linear regression model was estimated to examine associations between satisfaction, complaint usage, personal and sentence-related characteristics, and variables related to life in prison. The results of this model are presented in Table 4. Outcome-idealism had a positive effect on satisfaction, with increases in the perception that complainers receive what they want being associated with higher levels of satisfaction with the complaint system (b = 0.30, 95% CI = 0.23, 0.37, p < 0.001). In addition, a greater sense that rights are respected in prison was associated with greater satisfaction (b = 0.39, 95% CI = 0.31, 0.48, p < 0.001). Finally, confidence in prison staff was linked to greater satisfaction with the complaint system (b = 0.20, 95% CI = 0.10, 0.30, p < 0.001). Of these three predictors, the strongest was the respect for rights scale (β = 0.44), followed by the indicator of outcome-idealism (β = 0.34), and confidence in prison staff (β = 0.21).

Table 4. Linear regression model predicting satisfaction with the complaint system (n = 508)

Abbreviations: b, unstandardized regression coefficient; CI, confidence interval; LCI, lower confidence interval; SE, standard error; UCI, upper confidence interval.

* p ≤ 0.001.

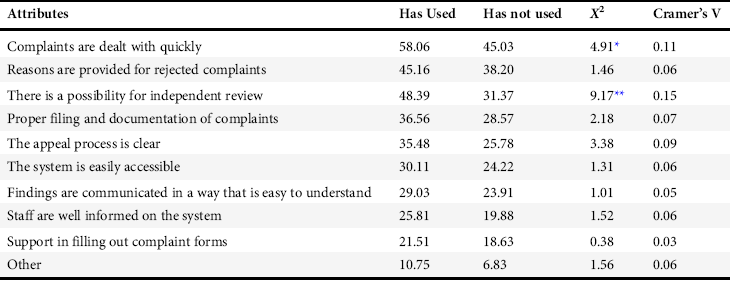

To further explore views on complaints, and to compare people in prisons' own views to the principles contained in international human rights standards, respondents were asked about the characteristics of a good complaint system. As shown in Table 5, regardless of complaint usage, the top three attributes were speed, offering reasons for rejected complaints, and access to independent reviews. However, some differences were found between those who had used the complaint system and those who had not. Although for both groups speed was the number one attribute, people in prisons who had used the complaint system placed significantly more importance on it (58.06% vs. 45.03%, X 2 = 4.91, p = 0.027). In addition, the percentage of respondents who considered independent reviews of the complaints important was 54.3% higher among those who had used the complaint system when compared to nonusers (48.39% vs. 31.37%, X 2 = 9.17, p = 0.002).

Table 5. Attributes of a good complaint system by complaint usage

*p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01.

Discussion

These findings indicate that the feelings of dissatisfaction with complaints procedures found in Californian prisons (Reference Calavita and JennessCalavita & Jenness, 2015; Reference Jenness and CalavitaJenness & Calavita, 2018) are also evident among people in prisons in Ireland, with a general lack of belief that the complaints system provides people with their desired outcome, and low levels of satisfaction with the system. The presence of a manifestation of procedural justice—the opportunity to complain—is therefore not enough to create a sense among people in prisons that they are likely to get a good outcome to a problem using such a mechanism. However, there is also some complexity here, with some groups more likely to overcome this general sense that the complaints system is ineffective as well as the broader barriers to mobilizing a complaint. Their characteristics raise interesting questions about what encourages a person to take the step of complaining. We also extend the literature on complaining in prisons and legal consciousness through our finding that having confidence in staff is associated with greater satisfaction with the complaint system, a finding which suggests that the situational context for a person's experience of complaints processes can be mediated through the activities of institutional actors, an insight which may have broader significance. We have also explored what people in prisons want from complaints processes with speed, reasons, and the opportunity to appeal being considered the most relevant, all classic features of a procedurally just administrative process.

Use of the complaint procedure

Slightly over one in five residents indicated having used the complaint system where they were currently imprisoned, which represents a nontrivial number of people with direct experience of a system which is generally regarded among people in prisons as unsatisfactory and unlikely to yield the desired results. It is of note that, unlike the US, there is currently no requirement for people in prisons to exhaust the internal complaints system to litigate. However, Reference Jenness and CalavitaJenness and Calavita (2018) argue that this is not a reason for high levels of grievance filing in their study. While this may be so, there are two very different cultures of prison litigation in Ireland and the US. In the former, litigation remains rare and only an emerging area of legal practice (Reference RoganRogan, 2014). Further comparative research is necessary to explore the links between litigation and complaints mechanisms, but differences in cultures of litigation and litigiousness which affect all aspects of dispute resolution in prison, may play a role in explaining this picture. Reference Dâmboeanu, Pricopie and ThiemannDâmboeanu et al. (2021), for example, argue that penetration of legal discourse on human rights in Romania in recent years has influenced complaining practices. Caution should be exercised in seeking to compare complaint usage to that found in other studies, specifically that of Reference Calavita and JennessCalavita and Jenness (2015), when there are methodological differences between the studies generating such findings. Further research which directly compares complaint usage across jurisdictions using comparable research designs, measures, and sampling approaches is necessary to explore precisely why there may be differences in how complaints are used, but such research should consider factors including whether the individual wishes to pursue an action before the courts, awareness of rights, and alternative ways of resolving issues, and the seriousness of the problems faced by incarcerated people in the different jurisdictions.

It is also clear, however, that complaint usage varies across people in prisons. In particular, we found that those with the longest sentences were significantly more likely to complain than those on sentences of 1 to 5 years. This is not surprising as a longer sentence means that there is more time for issues to arise and more time for people in prisons to familiarize themselves with the procedures available for handling complaints. Longer sentenced residents experience particular pains (Reference WarrWarr, 2020) and may have more incentive to complain. However, longer and life-sentenced people in prisons are probably those most acutely concerned about factors which may affect their release date, which depends, in part, on reports about their behavior while in prison. We may think this would be a powerful disincentive to making complaints; the reality of living in unsatisfactory conditions for long periods may trump those concerns, suggesting that the context of imprisonment may alter the barriers to complaining found in legal consciousness and legal mobilization literature.

It is also important to consider a practical factor: that the complaints system in Ireland is notable for its delays (Inspector of Prisons, 2016). Previous studies in the UK (Reference Morgan, Liebling, Morgan, Maguire and ReinerMorgan & Liebling, 2007), Romania (Reference Dâmboeanu, Pricopie and ThiemannDâmboeanu et al., 2021), and Australia (Reference NaylorNaylor, 2014) have found that those serving shorter-term sentences were less likely to complain with a lack of timely response as a factor. Our findings further show that the most important attribute for a complaints system identified by people in prisons is speed. Those serving shorter sentences may therefore not be filing complaints for reasons related to perceived delays. This finding should also be borne in mind by all those administering and designing complaints mechanisms in prisons, with particular attention needed for the situation of shorter-sentenced people in prisons. A deeper consideration also emerges, however, which relates to a key component of prison life and penal consciousness: time (Reference O'DonnellO'Donnell, 2014). Other studies have found that those who have served longer periods are more likely to complain, here, we have found that those who are sentenced to longer sentences are also more likely to complain. In a place where time may seem endless, getting an answer quickly may take on heightened importance than in other contexts which procedural justice scholarship have explored.

Another factor associated with usage of the complaint system is segregation, with those on protection more likely to complain than those in the general population. Individuals on protection are separated from the general population for grounds such as their safety or the safety of others and, as a result, may be restricted in accessing services and facilities in the prison. Previous research in the US and Australia has linked segregation with a poorer ability to adapt in prison (Reference Dhami, Ayton and LoewensteinDhami et al., 2007) and to worse psychological well-being (Reference Gullone, Jones and CumminsGullone et al., 2000). People on protection are subject to regimes which may impact on access to activities and the increase in the level of complaints may be a reflection of worse treatment or material conditions compared to that of the general population. The fact that such people may have more issues to complain about may explain this finding. Therefore, it is encouraging that people in this form of detention do feel able to access the complaint system. It might, however, provide further evidence of the challenging conditions which those in segregation face, with such people in prisons perhaps feeling particularly motivated to “fight back” against their conditions. Reference Calavita and JennessCalavita and Jenness (2015) note that the profound barriers against complaining in the prison context seem to be overcome when in particularly difficult circumstances. Protection, or segregation, is one of the most legally regulated parts of the prison experience, with this particular “hypervisibility” of law outweighing the social and psychological factors which reduce the likelihood of complaining. People living in these circumstances face the levers of legal power up close, law is far from remote (Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick & Silbey, 1998). As with Reference CowanCowan (2004), the feelings of powerlessness this position entails may prompt a desire to reinsert their agency into such processes, through one of the few available avenues. Negative experiences with the law have been found not to be a barrier to seeking its protection in other contexts (Reference KlambauerKlambauer, 2019). Those in segregation have often some of the most challenging relationships with penal authorities, yet are also seeking to hold those authorities to account.

Other demographic factors such as age, education level and nationality were also analyzed to identify differences between those who have used the complaints system and those who have not, finding no significant differences regarding these factors, aligning with Calavita and Jenness' finding (2018) that Black and White people in prisons were equally likely to complain. These findings add further credence to their position that a generalized sense of disenfranchisement is found across the prison population. This, however, stands in contrast to those from studies on the use of the Ombudsman among the general population. Previous studies have found that age and education are factors of significance when considering usage of the Ombudsman (Reference Buck, Kirkham and ThompsonBuck et al., 2010). Reference van Roosbroek and Van de WalleVan Roosbroek and van de Walle (2008), in a Belgian study of the general population, found that the majority of those who complained to the Ombudsman were older, middle-class men, with the majority having college education. This was in line with other research from the Netherlands, the UK, and Belgium (Reference van Zutphen, Andersen and Hubeauvan Zutphen, 2002). Further studies have also found that awareness of the office of the Ombudsman is lower among groups with lower levels of education (Reference Loois and SiebenLoois & Sieben, 2003). There seems, therefore, to be an difference between the general population and people in prisons, with people in prisons' demographic backgrounds playing less of a role in their likelihood of complaining, something also found by Reference Dâmboeanu, Pricopie and ThiemannDâmboeanu et al. (2021) in the context of Romanian prisons. One explanation may simply be that people in prison receive more information on, and more formal opportunities to learn about complaints procedures (e.g., through handbooks or information materials on entry into prison). In the context of the present study, complaint forms are available (or at least ought to be) on prison landings, with a box available to place complaints into. The complaints systems is also described in handbooks provided to prisoners on arrival, though the extent to which these are in fact offered or understood remains unclear. This extra visibility for complaints structures compared with most encounters with such mechanisms on the outside may be partially responsible for the fact that education level did not play an important role in participants' likelihood of making a complaint. Our study cannot account for whether the presence of such measures of visibility have played a role in overcoming educational disadvantage, and further research is necessary to explore the influence of such efforts. However, our findings suggest that more analysis of the use of awareness-raising activities on the outside and their influence on counterbalancing the effects of education level is warranted. It may also be, however, as Reference Calavita and JennessCalavita and Jenness (2015) suggest, that the experience of imprisonment plays an outsize role in increasing the likelihood of complaining. Class inequalities have been viewed as relevant in several studies of legal consciousness, but our findings suggest that it is not simply educational background which matters, but that background within particular institutional settings. Hull has argued that we need “greater elucidation of the links between social location and variation in legal consciousness within marginalized groups” (Reference HullHull, 2016, p. 569, emphasis in original). This study provides support for that claim.

Two variables related to life in prison were associated with complaint usage. These included perceived respect for rights and outcome-idealism. Specifically, complaint usage was linked to a lower sense that rights are respected in prison and lower agreements with the statement “prisoners who complain get what they want in prison.” This suggests that using the complaint procedure is negatively associated with a person's perception that the system might achieve a result for them. When coupled with the general low levels of satisfaction with the complaint procedure, we see that a complaints system can give rise to greater cynicism and a negative sense that one's rights are being protected. However, our findings do not speak to causal links and further longitudinal research is needed to better understand how using complaint procedures impacts views of such procedures, as well as other experiences in prison.

Low satisfaction with the complaint procedures

Overall, people in prisons viewed the complaints system negatively (the average score was 2.41, on a scale from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating more positive views). This research expands on prior findings (Reference Edgar, O'Donnell, Martin and MartinEdgar et al., 2003) about low trust in complaints bodies, by quantifying the level of dissatisfaction and using a larger, random sample of incarcerated people. It also adds to the picture from California and England and Wales that people in prisons do not have much faith in complaint procedures. This may have serious consequences, as poor experiences of procedural justice in prison could give rise to negative outcomes, including violence, anger, misconduct, and feelings that their imprisonment is not legitimate (Reference Beijersbergen, Dirkzwager, Eichelsheim, van der Laan and NieuwbeertaBeijersbergen et al., 2015; Reference BierieBierie, 2013), findings reflected in the Woolf report into riots in Strangeways prison in the UK (Reference WoolfWoolf, 1991).

However, our findings provide evidence that satisfaction with procedural justice systems can be mediated by people's relationships with institutional actors. Greater confidence in prison staff was linked to greater satisfaction with the complaint system, though there was not a significant relationship between confidence in staff and complaint usage. While prison literature has long attested to the importance of staff-prisoner relationships, how this operates in the context of using a complaints system has been subject to less analysis. Reference LieblingLiebling (2011) further notes the importance of procedural justice and respectful relationships as being critical to legitimacy in prisons. Here, we can add that views of mechanisms for complaining are correlated with good relationships between staff and people in prisons, suggesting that experiences of manifestations of procedural justice in prison and staff actions are closely intertwined. This finding further suggests that good staff-prisoner relationships are important to a wide variety of aspects of prison life, a finding relevant beyond Ireland.

More broadly, this finding further suggests that procedural justice literature also needs to engage more closely with the effect of pre-existing and ongoing relationships between the claimant and an institution's staff outside of the immediate context of the complaint (Reference Galovic, Birch, Vickers and KennedyGalovic et al., 2016). Our findings pose interesting questions for whether and how perceptions of complaints mechanisms in other domains, such as care homes or hospitals, are shaped by the actions of institutional actors outside the immediate confines of the complaint process.

In the current study two other variables were associated with levels of satisfaction. A positive relationship was found between satisfaction with the complaint system and outcome-idealism, indicating that those who more strongly believe that “prisoners who complain get what they want” report more satisfaction with the system. In addition, satisfaction was higher among those with a greater sense that rights are respected in prison. This latter finding suggests, as with relationships with staff, that a penal consciousness which experiences better protection of rights is connected to dispute resolution mechanisms. It may be that satisfaction with the complaint procedure influences a feeling that one's rights are protected, or that a general feeling that rights are protected is shared with a feeling that complaints procedures are working. While further research is necessary to untangle this complexity, the connections between feelings concerning rights and feelings concerning complaints show the need to understand the many factors which can shape experiences of rights in prison (Reference Piacentini and KatzPiacentini & Katz, 2017). Background characteristics, complaint usage, and the prison where the sentence was being served did not play a major role in this model, which accounted for 58% of the variance in views held among respondents.

What people in prisons want from complaint procedures

A key objective of this study was to explore what people in prisons themselves prioritized in the complaints system. In this way, we seek to make a contribution to the basis on which human rights standards, or other laws governing complaint procedures are developed. People in prisons ranked quick responses, getting reasons for a decision, and the possibility of independent review as the most important factors of a good complaint system.

These criteria are found, encouragingly, in the international human rights frameworks on the subject. Having a reason for a decision is a central plank of administrative justice, and, from this study, is something that matters in practice as well as theory and law.

The third most highly ranked feature of a good complaints system indicated by people in prisons was the possibility of an independent review. Currently, Ireland has no external element to its complaints system for incarcerated people, who are being expressly excluded from that remit of the Ombudsman (s. 5(1)(e)(iii) Ombudsman Act, 1980 as amended by Schedule I, Part II, (f)(ii) Ombudsman (Amendment) Act 2012).

Reference Calavita and JennessCalavita and Jenness (2018) reported the finding that the outcome was more important than the process to their participants, a finding in conflict with much procedural justice theory. Our findings also found that the outcome was more important, but the result was very close to the neutral point (3.4 on a scale of 1 to 5 where 3 reflects neither agree nor disagree). In this study, therefore, neither aspect was dominant. While we found ambivalence rather than a clear-cut preference for outcome, our finding, taking together with that of Reference Calavita and JennessCalavita and Jenness (2018) suggests that much more work is needed within that scholarship to fully apply the exhortation that “context matters” (Reference Calavita and JennessCalavita & Jenness, 2018: 11). It is also notable that people in prisons in our study are also expressing the desire for certain features of fair treatment. Our findings suggest that core aspects of procedural justice matter to people in prisons and it is of value to them to have quick, reasoned responses to their complaints, with access to independent review. These findings provide empirical evidence for these principles, and suggest that countries seeking to improve their complaints systems for people in prison should focus on a timely response, and the provision of reasons. Our findings also suggest that other countries may wish to introduce external review or appeals mechanisms to improve complaints systems in the eyes of people in prisons.

Limitations

Despite the novel findings of this research, a number of limitations should be noted. Due to the cross-sectional nature of the data, we can only assess associations and not causal relationships. Secondly, while participants were randomly selected within the prison, the facilities themselves were not randomly selected, and the survey was only distributed in English resulting in the exclusion of those who could not communicate in this language. As such, our findings are limited in their generalizability to incarcerated men fluent in English and held in medium-security prisons in Ireland. More research is needed using larger samples inclusive of low- and maximum-security prisons and residents who are literate in languages other than English. In our sample, some of the distributions were highly skewed (e.g., outcome-idealism) or unbalanced (e.g., nationality with few non-Irish respondents), reducing the statistical power to detect effects which may be present. Larger sample sizes might be particularly useful when skewed and unbalanced distributions are anticipated in order to minimize potential separation issues and increase the power to detect effects. In addition, certain variables which may impact on perceptions and experiences were omitted (e.g., type of crime, number of times in prison, time served, social support). Future research might overcome these limitations by using longitudinal designs and including additional variables in their instruments. Another limitation of our study is that it only allows to distinguish between complainers and noncomplainers but not among those who have complained several times or based on the complaint type or outcome. Future studies should analyze the types of complaints being made by those who make complaints in prison. Our study focused exclusively on incarcerated males. Previous research has found that male and female incarcerated people differ in several aspects (e.g., mental health, substance-dependence disorders, violence; Reference Binswanger, Merrill, Krueger, White, Booth and ElmoreBinswanger et al., 2010; Reference Wolff, Aizpurua, Sánchez and PengWolff et al., 2020), therefore research should replicate these findings with samples of incarcerated women to explore whether perceptions and usage of the complaint system differ by gender. This is particularly relevant as previous research in other jurisdictions suggests that incarcerated women and youth may be less likely to seek a review by the Ombudsman or know about the system to do so (Prison and Probations Ombudsman for England and Wales, 2015). Outside of prison, literature on legal mobilization also indicates that women are less likely to take steps to enforce their rights (Reference BumillerBumiller, 1987), and their reasons for not mobilizing might not be the same as men's (Reference NielsenNielsen, 2000). These insights should also be examined in the prison context.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes to the literature in several ways. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore complaint usage and perceptions among incarcerated people in Ireland, and one of the very few internationally. It examines how a wide range of personal and sentenced-related variables, as well as aspects related to life in prison influence attitudes towards the complaint system and impact its usage, offering fresh insights for procedural justice and legal consciousness work, as well as studies of law in action in the context of prison. By asking people in prisons what they considered important attributes of a good complaint system and contextualizing those with international legal frameworks, the current study offers practical guidance to inform the reform of the complaint systems, and offers information to those involved in drafting international and domestic law on the subject and who wish to incorporate the views of people in prison.

Conclusions

Theories of procedural justice and legal consciousness are only beginning to be applied in the context of imprisonment. This study provides a new perspective from Ireland, a place which does not have the same history of a nexus between grievances and litigation that is found in the US. We found that, even so, residents overall also have negative views of the complaint procedure in Ireland. Research in other jurisdictions would be valuable to help us understand the extent to which this dissatisfaction is specific to particular complaints or prison systems, and the degree to which this is a feature of the experience of being imprisoned. Dissatisfaction with complaints procedures is, furthermore, not simply a problem because it indicates human rights principles on complaints are being breached, but because of the serious practical consequences that may arise.

At the same time, we have also found that incarcerated people are using the complaints procedure, with those in some of the most challenging situations (serving long sentences; in segregation) being more likely to have complained. These findings suggest that, contrary to the tenets of much legal mobilization work, those who may be the most marginalized in prisons are more likely to elevate their grievance into a formal process. Reference Jenness and CalavitaJenness and Calavita (2018) conceptualize this finding as meaning that prison is a highly regulated environment wherein the hypervisibility of law outweighs reasons not to complain. Further research, particularly qualitative and mixed-method studies, can support analysis of why those who are perhaps at the “deepest end” (Reference CreweCrewe, 2012) of imprisonment are most likely to overcome the hurdles to complain. As such, we show that further engagement within groups engaged by legal consciousness scholarship is necessary to explore why this is the case. Further research with other groups outside prison who are in positions of particular marginalization on their likelihood of complaining is also warranted to assess whether this ability to overcome considerable barriers to complaining is something found at the extremes of human experience.

This study has also found that those who perceive their rights are respected are less likely to have complained and are also more satisfied with the complaints system. Those who had more confidence in prison staff also had greater satisfaction with the complaints system. These findings are important contributions to the literature on prison life, as well as being practically useful to those trying to improve prison regimes. They also speak to procedural justice theory. That scholarship, as noted in the context of policing, is beginning to situate procedural justice-related encounters within a wider context, such as experiences of systemic racism. Our findings indicate that this broadening of the lens is essential, and that a person's general experience of rights protections must be considered, as well as the role of institutional actors and their behavior outside of that immediate interaction giving rise to the application of procedural justice norms. As Reference SextonSexton (2015) argues, a person's experience of punishment depends on a range of factors; to this, we can now add that their experience of complaining in prison is associated with their view of the protection of their rights in prison more generally.

Our findings contribute to the literature on procedural justice and legal consciousness in two ways. First, complaints mechanisms are, at least under law, supposed to exhibit the core elements of procedural justice: one which provides an opportunity for people to put forward their case (Reference Thibaut and WalkerThibaut & Walker, 1975); which treats people with dignity; and which is neutral, and engenders feelings of trust (Reference Tyler and Allan LindTyler & Allan Lind, 1992). This study has found that a process which, ostensibly at least seeks to provide a measure of procedural justice in prison is largely disfavored by people in prison in Ireland. Our study adds that use of a complaints process that is generally considered unsatisfactory is linked with lower feelings that one's rights are protected, suggesting that either usage reduces feelings of respect for rights, or lower feelings of respect for rights results in complaints, with both interpretations showing a connection between complaints systems usage and legal consciousness. The present study also shows that, at least in prisons where there may be more sharing of experiences among people living in close proximity about complaints procedures than in the outside community, these negative perceptions are also shared by people who have not, in fact, used the system. This finding warrants further research in other settings to explore how perceptions of complaints systems are shaped among those who have not used them, and if there is something particular to the prison setting that explains this finding. Allied to this, we see echoes of Reference SaratSarat (1990), Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick and Silbey (1998) and Reference MerryMerry (1990) who show us that those who have experienced disenfranchisement have salient perceptions of “the law” in general, and Reference Trinkner and CohnTrinkner and Cohn's (2014) insight that our experience of legal socialization shapes our expectations of whether we will be treated by legal authorities with respect. As people with considerable experience of isolation from wider society, incarcerated people may be bringing their views of the law in general to their views of the complaints procedure in particular, something which is likely in Reference Sextonlight of Sexton's (2015) reminder to us that one's penal consciousness is intimately linked with pre-incarceration experiences. We add to calls in the literature that it is necessary to understand the context within which procedural justice is experienced at any particular moment (Reference Jenness and CalavitaJenness & Calavita, 2018).

A further contribution to the literature on legal mobilization and legal consciousness arises from our finding that unlike in other contexts, education level was not associated with a likelihood of engaging in legal mobilization in our study. This may be a factor of greater awareness of complaints processes in prisons due to the close quarters in which people live and the visibility of the architecture of complaints in the form of boxes visible on landings. Further research is needed into why education levels were nonsignificant, to assess whether the data are consistent with the hypothesis that greater raising of awareness of complaints procedures in the incarcerated world would mitigate against the effects of lower levels of education on the likelihood of making a complaint. This finding also warrants further research in other institutional settings and of awareness-raising activities to enhance our understanding of the role of education in legal consciousness and legal mobilization.

Our finding that there is an association between relationships between prisoners and staff and satisfaction complaints systems, but no association between confidence in staff and complaint usage also provides an avenue for further study outside the prison setting. Procedural justice literature emphasizes that a core element of it is trustworthiness, which concerns the relationship between the perceiver and the authority and perceptions of the attributes of the authority (Reference Tyler and Allan LindTyler & Allan Lind, 1992). The present study was conducted in a setting which is well known for the importance of relationships between staff and incarcerated people for a wide variety of outcomes. Our finding that prisoner-staff relationships are associated with views of the complaints system suggests that interactions between the public faces of the authorities and those who may complain can shape views of complaints structures generally. Reference Creutzfeldt and BradfordCreutzfeldt and Bradford (2016) suggest that complaints about public sector bodies may have more emotional resonance for the complainers than those about private service providers. We agree with calls from policing scholars (Reference Hickman and SimpsonHickman & Simpson, 2003) that attention needs to be given to the quality of day-to-day interactions between powerful authorities and the public.

We also suggest that, while outcomes matter a lot for people in prison, procedurally just treatment is also important to them. The findings also show that the attributes of a good complaints model that people in prisons place more importance on are speed, independent review, and reasoned rejections, with the first attributes being considered more important by those who have used the complaint system when compared to those who have not. The desire found here for independent review of complaints should be listened to, not only by the Irish authorities in their design of a new complaints system, but by others involved in the design and administration of such mechanisms to ensure that they are actually “genuinely available”, “accessible,” “trusted,” and “effective” (Council of Europe, 2018).

Acknowledgments

This article stems from the ‘Prisons: The Rule of Law, Accountability and Rights’ project, which has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 679362. We wish to offer our sincere thanks to the anonymous reviewers and editorial board members for their considered and helpful feedback. We are deeply grateful to members of the PRILA Consultative Council who reviewed the research instruments for this piece, in particular: Prof. Val Jenness, Prof. Kitty Calavita, Niall Walsh and Hugh Chetwyn, as well as Prof. Ben Crewe. We are very grateful to those who facilitated our research through the Irish Prison Service. Our deepest thanks to those who completed the survey and shared their experiences and views.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of the article at the publisher's website.