Introduction

Since the Mid Holocene, the Sahara's climate has been hyperarid, with a mean annual rainfall of between 0 and 20mm (Nicholson Reference Nicholson2011). This limited and unpredictable rainfall does not permit agricultural exploitation, other than in a few distinct ecological niches—the oases—where water availability is guaranteed by aquifers recharged during the Quaternary pluvials (periods of high precipitation). Today, the traditional subsistence strategy of contemporary human communities (the Tuaregs) living in the central Sahara involves the herding of ovicaprines that can subsist on the limited plant cover available (Nicolaisen Reference Nicolaisen1963; Gast Reference Gast1968). In the oases, however, the availability of water and the presence of soils protected from wind erosion have permitted agriculture since late prehistory (Cremaschi & di Lernia Reference Cremaschi and di Lernia1998; van der Veen Reference van der Veen1999). Mid to Late Holocene evidence for agricultural land-use of the Sahara is limited to these (palaeo-)oases; in other areas where herding was practised, evidence for agriculture is virtually absent (Cremaschi & di Lernia Reference Cremaschi and di Lernia1998; Mercuri Reference Mercuri2008).

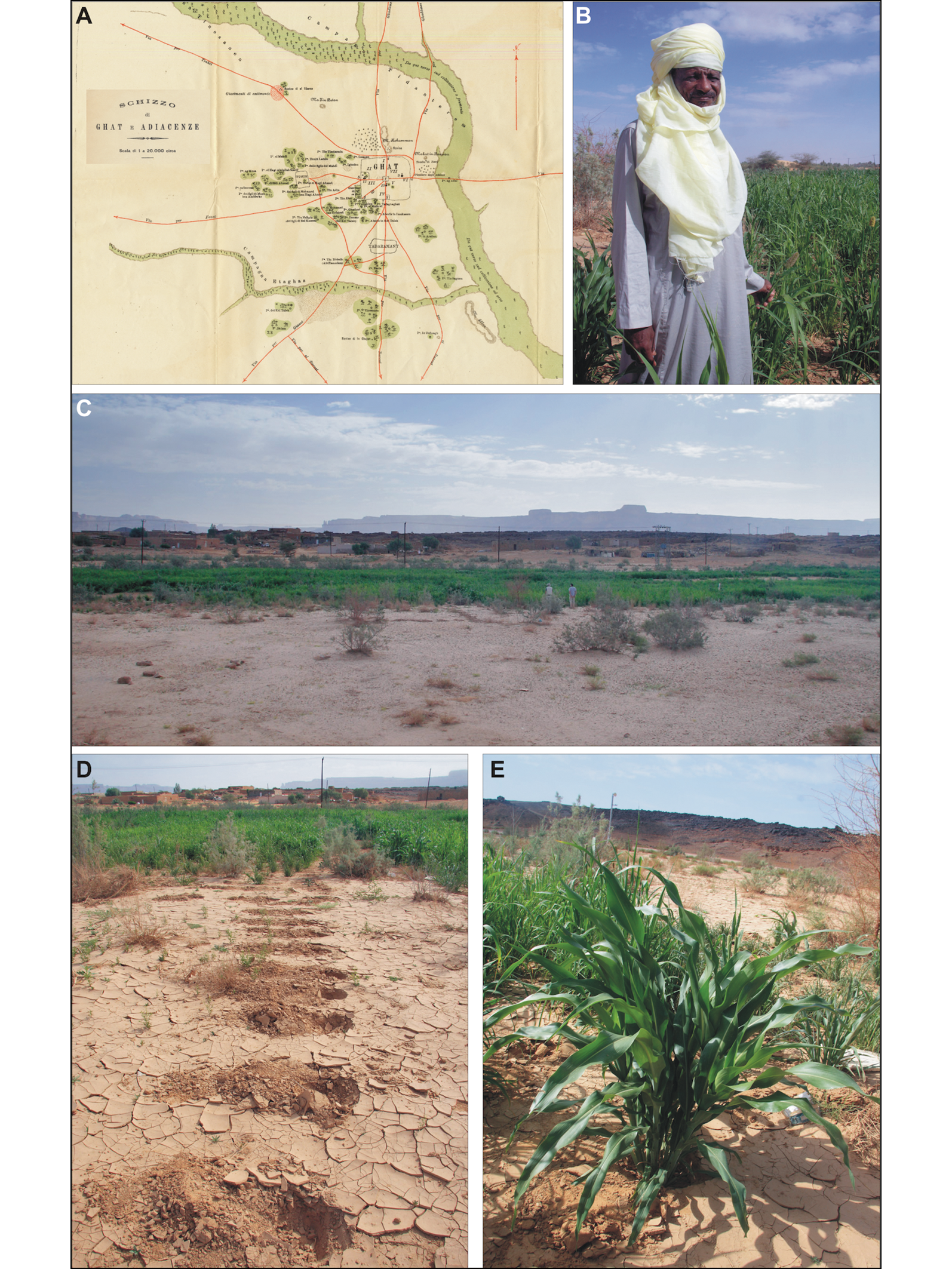

Although unpredictable, precipitation in the Sahara can be abundant, for example along the upper course of the Wadi Tanezzuft in south-west Libya, floods are historically recorded near the villages of Ghat and El Barkat (Figure 1). Such events can reactivate ephemeral drainage systems and feed temporary ponds with standing water for weeks (di Lernia et al. Reference di Lernia, N'Siala, Zerboni, Sternberg and Mol2012). Water remains inside the lowest parts of wadi beds, in basins cut in the bedrock or where sedimentary infilling of hollows retains moisture. The Tuaregs call these temporary ponds etaghas, also known as tesahaq or tmed (Camps Reference Camps1985). Early explorers identified etaghas as those parts of the wadi bed devoted to seasonal cultivation (Bourbon del Monte di Santa Maria Reference Bourbon del Monte Santa Maria1912). Further information about the exploitation of etaghas is scattered throughout early texts, most of them referring to the southern Sahara or the Sahel (Desio Reference Desio1942; Dubief Reference Dubief1953; Nicolaisen Reference Nicolaisen1963; Bernus Reference Bernus1979; Turri Reference Turri and Calegari1983).

Figure 1. A) Map by G. Bourbon del Monte di Santa Maria (Reference Bourbon del Monte Santa Maria1912) showing the location of cultivated etaghas at Ghat, corresponding to the green areas along valleys; B–E) photographs taken in 2010 of the same etaghas under cultivation (photographs courtesy of The Archaeological Mission in the Sahara, Sapienza University of Rome).

Our research in the Tadrart Acacus of the Libyan central Sahara (Figure 2) has found that, today, the Tuaregs occasionally cultivate a number of etaghas following heavy rainfall. This form of cultivation—never before reported from the hyperarid central Sahara—is probably based on traditional, local knowledge. The geomorphological properties of the etaghas facilitate rain-fed cultivation, allowing people living in the Tadrart Acacus to grow cereals and other crops. In the framework of a ‘desert ecomosaic’, in which our understanding of land-use is dominated by the oasis = agriculture vs desert = pastoralism dichotomy, the discovery of evidence for this practice in a hyperarid environment represents a breakthrough for our knowledge of the origins of Saharan agriculture. Here, we present the environmental aspects of the etaghas system, ethnographic knowledge about their use, ethno-geoarchaeological evidence for the most recent farming activities, and associated archaeological and rock art contexts. Our results demonstrate that, although seemingly marginal and remote, these fragile environments have long been exploited for cultivation. Our research also illuminates an unusual element of the natural and cultural landscapes of the Tadrart Acacus that may derive, little changed, from the Late Pastoral Neolithic period (c. 5900 cal BP).

Figure 2. A) Landsat satellite imagery of the Tadrart Acacus Mountains. Red stars: locations of the main etaghas; green squares: other occasionally flooded areas; blue triangles: long-term water resources; yellow dots: present-day Kel Tadrart campsites. B–E) GoogleEarth™ satellite imagery of the etaghas discussed; flooded areas are whitish, while parts actually cultivated are shown in green; major drainages are marked in blue.

Archaeological and ethnographic background

The Tadrart Acacus Mountains are located in south-west Libya (Figure 2), in the Sahara's hyperarid belt. The geology, physical geography and palaeoenvironments of the massif are summarised in the online supplementary material (OSM). In 1985, the Tadrart Acacus region was granted UNESCO World Heritage status on account of its magnificent rock art. The region has been a focus of research since the 1950s, with a particular focus on Late Quaternary human occupation, rock art, and the funerary practices and social systems of its later protohistoric phases (e.g. Mori Reference Mori1965; Cremaschi & di Lernia Reference Cremaschi and di Lernia1998; di Lernia & Manzi Reference di Lernia and Manzi2002; di Lernia & Zampetti Reference di Lernia and Zampetti2008). The Holocene human occupation in the region (Table 1; see also the OSM) is characterised by a long pre-Pastoral phase before the introduction of herding c. 8300 cal. BP. The Final Pastoral, with its transitional phases to the Garamantian (e.g. di Lernia & Manzi Reference di Lernia and Manzi2002; Liverani Reference Liverani2005), is marked by incipient social stratification. This is better documented in the Wadi Tanezzuft, where, from this phase onwards, there is evidence of cultivation along the oases (Cremaschi & di Lernia Reference Cremaschi and di Lernia1998; Mercuri Reference Mercuri2008). Little research has been dedicated to the study of the post-Garamantian and Islamic periods in the region, or to the modern Tuareg Kel Tadrart pastoralists.

Table 1. Phases of human occupation in the Tadrart Acacus and surrounding regions (modified after di Lernia Reference di Lernia2017).

Radiocarbon dating of archaeological contexts, together with rock art (bitriangular or horse style, followed by the camel style), and archaeobotanical evidence show a prolonged, albeit intermittent, human presence in the massif (di Lernia Reference di Lernia2017; Mercuri et al. Reference Mercuri, Fornaciari, Gallinaro, Vanin and di Lernia2018; Van Neer et al. Reference Van Neer, Alhaique, Wouters, Dierickx, Gala, Goffette, Mariani, Zerboni and di Lernia2020). The Tadrart Acacus was also inhabited after the complete desiccation of the region, which occurred c. 5500 cal BP. Culturally, this period, marked by the beginning of the Late Pastoral Neolithic, is characterised by the introduction of specialised ovicaprine pastoralism and incipient social stratification (Cremaschi & di Lernia Reference Cremaschi and di Lernia1998). The Tifinagh inscriptions—a Libyco-Berber alphabet mostly featuring in rock art and dating as far back as the early first millennium BC (Kaci Reference Kaci2007)—provide important information and insights into the surrounding landscape, as do later Arab writings. Both are visible close to water-rich areas (Biagetti et al. Reference Biagetti, Kaci, Mori and di Lernia2012; di Lernia et al. Reference di Lernia, N'Siala, Zerboni, Sternberg and Mol2012).

Methods

We analysed satellite imagery of the massif before undertaking field survey. In the field, we located and recorded, with the help of members of the local Kel Tadrart community (Mohammed ‘Skorta’ Hammadani and Ali Khalfalla), features relating to cultivation. We also gathered local archaeological data and collected samples for geoarchaeological and archaeobotanical analyses, and for AMS-radiocarbon dating (for further details on methods, see the OSM).

Results

Etaghas: distribution and main geomorphological features

Highly reflective ground surfaces, corresponding to light-coloured silty to loamy soils, are clearly visible on the satellite imagery. Potentially interpreted as etaghas, these are scattered over the massif (Figure 2). Only four such etaghas, according to our local guides, were traditionally exploited: Itkeri, Lancusi, Ti-n-Lalan and Ousarak (Figure 2), located in the central-southern range of the Tadrart Acacus (di Lernia et al. Reference di Lernia, N'Siala, Zerboni, Sternberg and Mol2012). Other areas in the region with similar geomorphological settings were not used for cultivation as their topsoils did not retain humidity due to the difficultly in protecting them against wind and grazing.

Cultivated etaghas, some 12–60ha in area and located in the lowest parts of the wadi bed, are relatively flat and free from stones (Figure 3). Their margins are close to the rocky wadi banks or dune slopes. Both offer protection from wind and sun exposure, thus reducing soil desiccation after rainfall. Guided by local knowledge, we observed that the maximum extent of the areas covered by the silty crust (the flooded areas) is more extensive than the cultivated surfaces (Figure 2). Agricultural activities are concentrated at the depocentre (area of maximum sediment deposition) of each etaghas, where soil moisture persists longest. In some cases, the remnants of the most recent episodes of cultivation are still evident, including the alignments of holes, each represented by a shallow depression where a single plant was grown (Figures 3–4).

Figure 3. Photographs of etaghas: A–B) Lancusi; C) Itkeri; D) Ti-n-Lalan (photographs courtesy of The Archaeological Mission in the Sahara, Sapienza University of Rome).

Figure 4. Photographs of functional areas and anthropic markers: A) cultivation holes and markers at Itkeri; B) remains of a stone enclosure at Ti-n-Lalan; C) Final Pastoral querns and scatter of lithics at Itkeri; D–E) threshing areas at Ti-n-Lalan and Itkeri; F) straw in a threshing area at Ti-n-Lalan; G) field boundary at Itkeri (photographs courtesy of The Archaeological Mission in the Sahara, Sapienza University of Rome).

Ethnographic narratives of etaghas exploitation

According to our local Kel Tadrart Tuareg guides, human presence around the etaghas is mostly characterised by small campsites (Figures 4–6), field features (walls, ditches, fences, stone markers), a low density of artefacts (e.g. pottery sherds, grinding equipment, lithic tools), rock art and designated areas for plant processing. The Tuareg Kel Tadrart cultivated a variety of crops, such as Tadrart Asian wheat and barley, as well as sorghum and millets, as confirmed by our ongoing ethnobotanical study (di Lernia et al. Reference di Lernia, N'Siala, Zerboni, Sternberg and Mol2012). Ethnographic information suggests that yields, albeit fluctuating, can be sizeable: wheat and barley, for example, can produce some 10–15 quintals per hectare (Nicolaisen Reference Nicolaisen1963). Considering the low density of people living in the Tadrart Acacus, with ethnohistorical and ethnoarchaeological sources suggesting around 50–90 people or 10–12 families (Scarin Reference Scarin1934; Biagetti Reference Biagetti2014), the yields of the etaghas may have represented an important additional, if unpredictable, resource.

Figure 5. Archaeological evidence associated with etaghas: A) Final Pastoral campsite at Lancusi; B) Final Pastoral/Early Garamantian campsite at Itkeri; C) Final Pastoral/Early Garamantian stone features at Itkeri; D) quern at Itkeri; E) Final Pastoral pottery at Itkeri; F) Final Pastoral/Early Garamantian pottery at Ti-n-Lalan (photographs courtesy of The Archaeological Mission in the Sahara, Sapienza University of Rome).

Figure 6. Rock art panels close to the etaghas: A–B) engravings at Ti-n-Lalan; C) pecked outline of cattle (possibly Garamantian) at Itkeri; D) pecked engraving of cattle (possibly Final Pastoral) at Itkeri; E) Tifinagh and Arabic inscriptions at Lancusi; F) Final Pastoral/Early Garamantian bitriangular-style paintings at Lancusi (photographs courtesy of The Archaeological Mission in the Sahara, Sapienza University of Rome).

Following rain, several men from different localities gather in the most flooded etaghas to prepare the fields and begin sowing, a phase normally lasting around four weeks. The seeds are sown in small holes dug by hoe (Figures 3–4); in the past, the Kel Tadrart used a digging stick made of tamarisk (Tamarix sp.) wood. The etaghas are enclosed by ditches or wooden poles with barbed wire. The last ditch was dug more than 60 years ago at Ti-n-Lalan. Called ahàrum in Tamasheq (andak in Arabic), the ditches comprise two parallel trenches 1 and 0.5m wide respectively, the outermost approximately 1.8m deep, the other much shallower. Several people are needed to dig such ditches by hand, using iron hoes and picks. Before the widespread use of iron tools, ditches were dug using large cutting stones. Once the fields are sown and enclosed, a few wardens remain in the vicinity for up to three months to prevent animals from grazing. Their salary, paid in seeds, is calculated on the basis of crop yield. If the harvest is good, the wardens can each receive one azad (kell in Arabic), a wooden bowl used as a unit of measurement of approximately 6kg; with poor yields, payment could be as low as 1kg.

The harvesting techniques depend on the type of crop. For wheat, the tops and ears are cut, and the basal part left in the ground for camels to graze. For millets, the entire stem is left, with only the ears removed. Many people, including women and elders, participate in the harvest, which takes approximately one month. Three weeks are needed to dry the harvested plants in areas marked out by stones; such areas are potentially identifiable in the archaeological record. After drying, the ears are threshed for three to four days directly on the sand by continuous trampling by camels—a process that produces subcircular accumulations of straw. Special meshes, known as azuzar, are used for winnowing. Physical evidence for this ethnographic narrative is provided by plant-processing areas still visible at Lancusi, Itkeri and Ti-n-Lalan (Figure 4). The entire operation represents a complex social investment: normally, the Amenokal (the head of the clan or tribe) selects an individual—the Amghar etaghas—to coordinate and direct the work, and to settle possible disputes.

Archaeological and ethnoarchaeological evidence

Itkeri

The etaghas of Itkeri are significant in Kel Tadrart social memory, probably because they flooded more frequently than others, and dozens of people worked together to cultivate them. Regularly positioned stone alignments and wooden posts form a quadrangular pattern enclosing cultivation holes (Figure 4). Further evidence of human activity at Itkeri includes the remains of field boundaries made of stones and wood fences, grinding stones, hearths and ceramic fragments (Figures 4–5). A natural rock face at the edge of the etaghas displays a few engravings showing camels, concentric rings and Tifinagh and Arabic inscriptions (one of which refers to the year ‘1962’). Close by, a circular stone structure displays a double natural patina (dark and red rock varnishes), which in the region is indicative of the structure's first use in a Late to Final Neolithic Pastoral phase (see Zerboni Reference Zerboni2008). More than 20 stone structures, including rings, enclosures, windbreaks and a cairn, are present along the edges of the etaghas. Scattered among the stone structures, we identified several lower grinding stones and some 40 pottery sherds. These are mostly thin, undecorated pieces with a depurated fabric and greyish surfaces, suggesting that they belong to a Final Pastoral/Formative Garamantian occupation phase (Figure 5). A few sherds in the later Tuareg tradition are thick, coarse and with reddish surfaces. The specialised areas for plant processing are characterised by the presence of substantial sub-circular accumulations of straw, consisting of clusters of rings, whose raised rims are formed by a dense mixture of straw and sand (Figure 5). The rocky edges on the flanks of the etaghas show several unvarnished rock markings, mostly of Tifinagh script and of camels. A few engravings of cattle (sometimes with pecked outline) covered with a red rock varnish belong to the Final Pastoral/Early Garamantian style (Figure 6C–D). At the etaghas’ northern margin, approximately 15m from the cultivated area, is a small rockshelter containing a sandy deposit capped by an accumulation of straw and ovicaprine dung with coarse charcoal and ash lenses.

Lancusi

At Lancusi, recent cultivation holes extend across only a small area of the etaghas system (Figure 3), probably because drifting sand has covered former cultivation areas. According to local informants, the Lancusi etaghas rarely floods and is exposed to the incoming windborne sand. It was therefore only occasionally cultivated. Two main areas of plant processing are visible in the northern part of the etaghas, covering a surface of approximately 0.4ha. Three rocky hills border the etaghas, and their southern flanks (not visible from the etaghas) host rock art dating to the Early to Middle Pastoral period (Mori Reference Mori1965). Camel-style engravings and Tifinagh script of a later date are also common. We collected fragments of Final Pastoral/Early Garamantian pottery from two areas of the etaghas. Furthermore, a stone structure exhibits a reddish-black rock varnish, which suggests a Final Pastoral date. Several such structures, often located close to natural rock faces, along with enclosures for goats, testify to past Tuareg occupation.

Ti-n-Lalan

The area of Ti-n-Lalan has been known since the 1950s for its abundant rock art (Mori Reference Mori1965). Previously known as Anejjer (the Tuareg word for ‘running water from rainfall’), its present name has a different meaning: ‘a stopping place for caravans to leave their luggage’, because the area is rich in water (Ali Kaci pers. comm.). Ti-n-Lalan was last cultivated in 1966. We surveyed this area twice, and once more after a light rainfall, which offered the opportunity to observe a flooded etaghas (Figure 3D). The limits of the crust-covered area identified in the field are consistent with satellite imagery and correspond to the extent of the cultivated surface. A few residual accumulations of straw at the northern margin of the etaghas are present. The archaeological record consists of isolated scatters of pottery sherds (Figure 5), with 15 fragments clearly indicating a Final Pastoral/Early Garamantian occupation. Several rock art panels (Figure 6), Tifinagh engravings and other rock markings are located along the edges of the etaghas. Although their position alone cannot be considered as evidence of association, their stylistic traits appear to be mostly late prehistoric; such depictions and others in bitriangular and camel style suggest an early phase of etaghas exploitation, as also indicated by the 15 ceramic fragments.

Ousarak

We had limited access to this southernmost etaghas due to its proximity to the Algerian border. Ousarak covers approximately 100ha, is flanked by a huge composite dune and is only cultivable after sustained rainfall. Once more, there is a discrepancy between the areas potentially suitable for cultivation, as identified in the satellite imagery, and the areas cultivated. A small Middle to Late Pastoral campsite, located close to the dune slope, is attested by nine hearths and a few sherds and lithics. Although the link between the cultivated area and the site is only speculative, it must be emphasised that it is the only site within a large area that is close to the etaghas. The geomorphological features of the area probably made this a suitable location for plant cultivation, possibly from the Middle to Late Pastoral period.

Geoarchaeology

At the Ti-n-Lalan, Lancusi and Itkeri etaghas, we opened test trenches in the middle of the cultivation areas to expose the natural pedosedimentary record at the depocentre of flooded depressions (Figure 7). The topsoil consists of poorly laminated silt and sand, a few centimetres thick, with a distinct interface between the underlying, 0.20–0.40m-thick clayey-silt horizon. Occasionally, 10mm-thick clayey/sandy lenses and a few concentrations of small charcoal fragments are present. The natural pedosequence includes buried former topsoils that, like the present-day topsoil, display poor pedogenesis. This is due to the local pedoclimate (Zerboni et al. Reference Zerboni, Trombino and Cremaschi2011), and the short period of time that surfaces were exposed between flooding events. At the microscopic scale, sedimentary layers show a sequence of some 50mm-thick horizontal laminae, with an upward fining trend (i.e. the grain size decreases towards the top) related to sediment particles settling in shallow water. Such decantation laminae are sometimes vertically displaced and disrupted by vertical cracks filled by coarse particles. Micro-charcoals are embedded in the finer part of each decantation lamina, along with horizontally oriented phytoliths and plant remains. Bioturbation voids, calcium carbonate (CaCO3) redistribution along root casts, and a few dusty clay coatings on voids are present (Figure 7C–F).

Figure 7. Cultivation holes (A) and (B) a test trench at Lancusi; photomicrographs showing decantation laminae (C), their disruption (D–E) and the occurrence of micro-charcoals (F) (photographs courtesy of The Archaeological Mission in the Sahara, Sapienza University of Rome).

Threshing areas were well preserved at Itkeri (Figure 8), whereas their original shape is unclear at Ti-n-Lalan. Both were investigated by sectioning their external rims. Beneath the rims, we recorded a sandy-silty layer with a platy structure, many vesicles and evidence of mechanical compression. Microscopically, the straw rims comprise a sandy matrix including a variable percentage of fresh plant remains. In some cases, these rims exhibit superimposed lenses of straw and sand, corresponding to successive threshing phases. Plant remains are finely subdivided and include seeds and husks. At Itkeri, we found a few deformed ovicaprine pellets within straw accumulations, suggesting that goats were allowed to graze the area after threshing.

Figure 8. A) Threshing circles at Itkeri visible on GoogleEarth™ satellite imagery (white arrows), along with residential structures (black arrow) and a cairn (yellow arrow); B) photograph of threshing circles at Itkeri; C) stratigraphic section excavated along a threshing rim at Itkeri (with white squares referring to samples of D–E); D) photomicrograph of straw-supported groundmass; E) photomicrograph of sand-supported groundmass; F) deformed coprolite (photographs courtesy of The Archaeological Mission in the Sahara, Sapienza University of Rome).

The fill of the rockshelter near the Itkeri etaghas consists of a sand dune covered by anthropogenic sediments (Figure 9). The top of the dune is bioturbated and contains a straw-supported sandy deposit. It also contains a dung layer similar to those described at many sites in the Tadrart Acacus region (Cremaschi et al. Reference Cremaschi, Zerboni, Mercuri, Olmi, Biagetti and di Lernia2014). It includes a lower part with straw and sand, with charcoal fragments and undecomposed straw remains becoming more abundant towards the top; the latter remains are associated with faecal spherulites and calcium oxalate druses (i.e. groups of oxalate crystals) (Figure 9), suggesting the presence of ovicaprine dung.

Figure 9. A) The rockshelter at Itkeri and (B) stratigraphic sequence within. Photomicrographs of samples collected from this section: C) dismantled coprolites; D) faecal spherulites; E) straw; F) charcoal (photographs courtesy of The Archaeological Mission in the Sahara, Sapienza University of Rome).

Radiocarbon dating

Charcoal fragments were sampled from the dung-bearing layer of the stratigraphic section of the Itkeri rockshelter. The date obtained is 1700±25 BP (Table 2; UGAM8712a; 318–402/256–299 cal AD), a period during which the Garamantes exploited the region (Mattingly et al. Reference Mattingly, Daniels, Dore, Edwards and Hawthorne2003; Mori Reference Mori2013). It therefore provides a terminus ante quem for the deposition of the straw layer recorded below the accumulation of dung (Figure 9B). Two samples (UGAM8710, UGAM8711) of charcoal collected from Ti-n-Lalan and Itkeri (at a depth of 0.10–0.25m), provide modern dates, suggesting a recent deposition.

Table 2. Radiocarbon dates from the Tadrart Acacus, from the end of the Late Pastoral to post-Garamantian contexts (modified after Biagetti & di Lernia Reference Biagetti and di Lernia2013); calibration using OxCal v4.3 and the IntCal13 calibration curve (Bronk Ramsey & Lee Reference Bronk Ramsey and Lee2013; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer2013). LP = Late Pastoral; FP = Final Pastoral; EG, G, PG = Early Garamantian, Garamantian, Post-Garamantian.

* First published in this article.

Etaghas: a legacy of an ancient land-use?

The etaghas of the Tadrart Acacus are one of the most remarkable indications of land-use so far documented among traditional societies inhabiting arid lands. In the hyperarid Saharan ecosystem, agriculture has long been considered as confined to the oases (Harlan & Pasquereau Reference Harlan and Pasquereau1969; Salmon et al. Reference Salmon, Friedl, Frolking, Wisser and Douglas2015). Therein, we may distinguish irrigated cultivation from flood-recession (or décrue) cultivation. The latter is common in the Sahel, close to permanent and seasonal rivers. It is, for example, present along the Senegal and Nile Rivers, and has been reported in the Mediterranean Basin (Baldy Reference Baldy1997). On the land-use maps of North Africa (Permanent Interstate Committee for Drought Control in the Sahel 2016), agricultural land-use is not recorded for the Sahara; pastoralism is the only type of human exploitation reported for the region; alternatively, blank areas on the maps of North Africa may suggest a virtual absence of human life and forms of subsistence.

Although flood-recession cultivation is known across the Sahel and in other locations receiving much flood water, the etaghas cultivation system seems to be unique to the central Sahara. Given the geomorphological and physiographic features of etaghas, only occasional rainfalls can reactivate the surface hydrology. In these terms, we consider the etaghas system as an example of rain-fed agriculture. The occasional flooding of areas that are depressed and protected from winds allows moisture in the topsoil to be retained for several weeks, thus making cultivation possible.

The social memory of the present-day Kel Tadrart suggests that local rain-fed agriculture dates back many generations, although they are unaware of its antiquity. While radiocarbon dating of our samples from the Ikteri and Ti-n-Lalan etaghas does not indicate a prehistoric exploitation of the etaghas system, the dung deposit resulting from keeping animals in the rockshelter at Itkeri—radiocarbon-dated to Garamantian times—suggests by association that the use of etaghas for cultivation goes far back in time. Final Pastoral Neolithic and Garamantian pottery found in many localities and ancient rock art also suggest that use of the etaghas had early precedents. Geometric drawings at Itkeri (see Figure 10), for instance, could be cautiously interpreted as representing partitioned fields with cultivation holes.

Figure 10. A–B) Putative field boundaries and cultivation holes painted at Itkeri (rock art digitally enhanced using DStretch©); the arrow probably indicates a cultivation hole with plant shown in situ; C–D) cultivation holes at Lancusi and Itkeri (photographs courtesy of The Archaeological Mission in the Sahara, Sapienza University of Rome).

The notion of late prehistoric cultivation of domesticated Asian and African crops in the region is intriguing. Although Saharan cultivation of wild cereals by Early Holocene foragers is attested (Mercuri et al. Reference Mercuri, Fornaciari, Gallinaro, Vanin and di Lernia2018), less is known about agriculture during Holocene arid periods. The Saharan Pastoral Neolithic is traditionally considered to have been characterised by herding (di Lernia Reference di Lernia2001, Reference di Lernia2017), with only a few cultivation experiments associated with palaeo-oases. Archaeological evidence in the Wadi Tanezzuft points to agricultural land-use dating to the Final Pastoral Neolithic, in a context of increasing sedentism. The configuration and distribution of sites dating to this period suggest intensive land exploitation. Such sites have yielded hearths, storage pits, grinding equipment, lithic hoes and gouges—all associated with cultivation and crop processing (Cremaschi & di Lernia Reference Cremaschi and di Lernia1998). At the microscopic scale, buried palaeosoils from Final Pastoral Neolithic sites preserve pedofeatures suggestive of rudimentary soil-management practices (ploughing and burning the plant cover; Cremaschi & Zerboni Reference Cremaschi and Zerboni2009). The cultivation of date palms and selected cereals also dates to the Final Pastoral in the Wadi Tanezzuft, and to the Final Pastoral/Formative Garamantian across the wider region (van der Veen Reference van der Veen1999; di Lernia & Manzi Reference di Lernia and Manzi2002; Liverani Reference Liverani2005).

Final Pastoral Neolithic groups probably experimented with cultivation along the Wadi Tanezzuft to supplement their pastoralist subsistence strategy (Cremaschi & di Lernia Reference Cremaschi and di Lernia1998). At that time, the Wadi Tanezzuft was seasonal. Alternating flooding and dry periods (Cremaschi & Zerboni Reference Cremaschi and Zerboni2009) allowed for recession cultivation on its alluvial plain. At that time, the valleys of the Tadrart Acacus were arid, with rivers activated only during seasonal rainfall (Zerboni et al. Reference Zerboni, Perego and Cremaschi2015). In such environmental conditions, the lowest parts of the wadis were probably flooded to a greater extent than they are today, with soil moisture persisting for a few months. More frequent and intense flooding events along the wadis of the Tadrart Acacus therefore allowed Final Pastoral Neolithic (and later Garamantian) groups to establish seasonal décrue cultivation.

Albeit sparse and circumstantial, our geoarchaeological results support the hypothesis that the central Saharan etaghas cultivation system is rooted in the Late Holocene. This developed gradually, under conditions of progressive aridification, from recession cultivation towards a rain-fed system based on collecting rainwater. This transition may have enhanced the ability of human groups to optimise residual or occasional water resources through introducing a system of rainwater collection that is still present in the social memory of Tuaregs.

The possibility that this cultivation system was introduced from other Saharan massifs or sub-Saharan areas where populations practised flood-recession agriculture must, however, be considered. Nonetheless, rain-fed agriculture in the Tadrart Acacus appears to have been adopted independently as an adaptation to local conditions, even though evidence supporting such a hypothesis is currently scant. The archaeological record of the central Sahara suggests that the exploitation of plants has an extraordinarily long and unique tradition, with Early Holocene evidence for wild cereal cultivation (Mercuri et al. Reference Mercuri, Fornaciari, Gallinaro, Vanin and di Lernia2018). Moreover, many important innovations in subsistence strategy emerged in the Tadrart Acacus, including the taming and corralling of wild Barbary sheep and evidence for Africa's earliest dairying (di Lernia Reference di Lernia2001; Dunne et al. Reference Dunne, Evershed, Salque, Cramp, Bruni, Ryan, Biagetti and di Lernia2012; Rotunno et al. Reference Rotunno, Mercuri, Florenzano, Zerboni and di Lernia2019). Ultimately, the Tadrart Acacus Final Pastoral Neolithic groups’ intimate knowledge of their environment and its resources provides the best explanation for the emergence of rain-fed cultivation of crops in the region.

Conclusion

Our investigations in the hyperarid Tadrart Acacus have revealed a feature of marginal desert land-use, the etaghas, where occasional cultivation is used to supplement herding. The present-day Tuaregs cultivate small areas of desert following sporadic rain-fed flooding events, but etaghas cultivation is much older. While radiocarbon dating suggests that these features were cultivated in Garamantian times, material culture and rock art provide circumstantial evidence to push back the date for the origin of local rain-fed agriculture to late prehistory.

This ancient land-use in the Tadrart Acacus may represent the legacy of a Pastoral Neolithic subsistence strategy inherited from flood-recession-based cultivation and sustained into the Late Holocene by seasonal rainfall. The progressive decrease in such rainfall and its increasingly erratic occurrence may have initiated a switch from recession cultivation to a rain-fed system. The agricultural use of the etaghas provides a snapshot of the dawn of agriculture in the Sahara, offering new insights into the multifaceted subsistence strategies of herding groups and their deep knowledge of local natural resources. Our findings confirm the complexity of land-use strategies adopted by traditional societies in the Tadrart Acacus, and serve as a warning against generalisation and oversimplification when interpreting human exploitation of marginal natural environments.

Acknowledgements

The etaghas project was conducted in 2008–2010 by the Italian-Libyan Mission in the Acacus and Messak of the Sapienza University of Rome and the Libyan Department of Archaeology; the latter supported fieldwork and permitted the export of samples. The Sapienza University of Rome and the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs funded the research. S.D.L. designed the research and directed the fieldwork; S.D.L. and A.Z. wrote the paper; I.M.S. collected botanical data in the field; and A.M.M. advised on ethnobotany.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2020.41.