1. Introduction

Fictions are normally not constrained by what the actual world is like. There are fictions where World War II never took place and those where it was won by Germany. There are even fictions in which facts we know to be impossible obtain, such as that water is not H2O and in which faster than light space travel is real. However, authors seem to be curiously restricted concerning the evaluative layout of the worlds described by their fiction. Richard Moran illustrates the point in the following way:

If the story tells us that Duncan was not in fact murdered on Macbeth’s orders, then that is what we accept and imagine as fictionally true. If we start doubting what the story tells us about its characters, then we may as well doubt whether it’s giving us their right names. However, suppose the facts of the murder remain as they are in fact presented in the play, but it is prescribed in this alternate fiction that this was unfortunate only for having interfered with Macbeth’s sleep, or that we in the audience are relieved at these events. These seem to be imaginative tasks of an entirely different order. (Reference Moran1994, 95)

The focus point of the discussion of imaginative resistance has been moral values, but as observed by, among others, Stephen Yablo, the phenomenon is not specifically moral:

“All eyes were on the twin Chevy 4×4’s as they pushed purposefully through the mud. Expectations were high; last year’s blood bath death match of doom had been exhilarating and profound, and this year’s promised to be even better. The crowd went quiet as special musical guests ZZ Top began to lay down their sonorous rhythms. The scene was marred only by the awkwardly setting sun.” Reading this, one thinks, “If the author wants to stage a monster truck rally at sunset, that’s up to her. But the sunset’s aesthetic properties are not up to her; nor are we willing to take her word for it that last year’s blood bath death match of doom was a thing of beauty.” (Reference Yablo2008, 143)

Why is it that authors are unable to alter the evaluative truths in the world described in their fiction, in the manner illustrated by Yablo above? This is the problem of imaginative resistance.

In this paper, I offer a semantic of explanations of this phenomenon, according to which it is special semantic features of evaluative terms and properties that give rise to it. Specifically, I outline a sensibilist semantics of evaluative terms which relies on recent discussion regarding predicates of personal taste and argue that it accounts for the phenomenon. In essence, the diagnosis of imaginative resistance I offer is as follows: when entering a fictional story, we leave our beliefs about what the world is like behind, while taking our actual emotional attitudes with us into the fiction. Sensibilism, as I will understand it here, is the view that the way we feel about things determines their evaluative properties. When making up our mind about the extension of evaluative properties in nonactual worlds, we use our own feelings. It is the attitudes we hold in the actual world that fix the extension of evaluative properties, even in nonactual worlds.

I first provide a general motivation for this diagnosis inspired by an observation made by David Hume. Second, I outline a sensibilist semantics for evaluative terms based on the semantics for taste predicates outlined by John MacFarlane (Reference MacFarlane2014). Third, I show how this semantics, extended to evaluative terms in general and in combination with a common view of fictional discourse, accounts for imaginative resistance. Thereafter, I discuss some alternative explanations of imaginative resistance and argue that the current proposal has some distinct advantages over these. In the final two sections, I examine some non-evaluative examples of imaginative resistance, as well as some alleged counterexamples to the phenomenon, and discuss how my theory should diagnose them.

Before all this, however, it is important to be clear on exactly what the problem with the vignettes is supposed to be. Brian Weatherson (Reference Weatherson2004) helpfully distinguishes between two different puzzles.Footnote 1 First, there is the imaginative puzzle, which concerns the difficulty we have in (propositionally) imagining the relevant stories. It is from this puzzle that the name of the phenomenon derives. Secondly, there is the alethic puzzle (sometimes also called the fictionality puzzle), which concerns the question of why the author’s authority breaks down when it comes to normative and evaluative matters. Why is it that she fails to make it true in the fiction that, for instance, the death match of doom was a thing of beauty? In the following, I will focus on the alethic puzzle rather than the imaginative one. There are two reasons for this. First, as noted by several authors, it seems that we have no trouble supposing that ZZ Top’s rhythms are sonorous, or any of the other relevant cases (cf. Gendler Reference Gendler2000, 80).Footnote 2 So whatever one takes imagination to be, it must therefore be something different from mere supposing. I do think that there is a “more engaged” form of propositional imagining than mere supposing and that it is in indeed difficult to represent the problematic cases above with this faculty. It is, however, difficult to delineate the difference between supposing and imagining more precisely. Accordingly, it is difficult to obtain a good grasp of the imaginative puzzle. Secondly, in their empirical study of imaginative resistance, Hanna Kim and her co-authors find that for evaluative and non-evaluative cases which subjects find equally unusual, surprising, and distant from the actual world, there is no significant difference in the extent to which they find them difficult to imagine (Kim, Kneer, and Stuart Reference Kim, Kneer, Stuart, Cova and Réhault2018). This can be taken to indicate that there is no imaginative puzzle that concerns the evaluative in particular.

By contrast, the sort of breakdown of the author’s authority that we see in the evaluative cases makes them different from most non-evaluative propositions which we find hard to imagine. In the evaluative cases, is not only that we struggle to imagine what is described, but we also feel like the author is going out of bounds when making the relevant statements. “The aesthetic properties of the sunset are not up to her,” as Yablo puts it in the quote above. In addition, the aforementioned study did find a statistically significant difference in the extent to which the subjects took the relevant evaluative and non-evaluative claims to be true in the fiction. Even for the non-evaluative claims that the subjects find hard to imagine, they are not inclined to deny that the claims are true in the fiction to the same extent that they are for the evaluative cases. This supports the notion that the central problem of imaginative resistance, relating specifically to the evaluative, is the alethic puzzle.Footnote 3 This is what I will focus on.Footnote 4

Another remark about the nature of the problem is appropriate here. When we say that the author is not in a position to change the evaluative properties of a sunset, this should be taken in a certain sense. The author can certainly change the way sunsets look. She can, for instance, make it the case that the air is full of some sort of gas which makes the sunset have a colour in-between green and brown. If she does that, then she can also change the aesthetic qualities of the sunset. What she cannot do is to let the relevant non-evaluative properties of the sunset be the same and only change the evaluative properties. It is an often-noted feature of fiction that unless provided with explicit information to the contrary, truths are normally imported from the actual world. In reading Yablo’s scene above, we normally assume that the sunset has the same non-evaluative visual properties as it would have in the actual world. The exact workings of this “importation” of truths from the actual world is a contentious issue (see for instance Friend [Reference Friend2017] and the references therein). It is important to recognise that unless we import these kinds of background truths from the actual world in cases like the above, they do not give rise to imaginative resistance. If we allow ourselves the assumption that sunsets do not look the way they do in the actual world in Yablo’s fiction, then we are also happy to go along with the author’s claim about its divergent evaluative aesthetic properties.

2. Sensibilism

As stated above, the diagnosis of the puzzle that I will offer turns on an observation first made by Hume. Here is the relevant passage:

Where speculative errors may be found in the polite writings of any age or country, they detract but little from the value of those compositions. There needs but a certain turn of thought or imagination to make us enter into all the opinions which then prevailed and relish the sentiments or conclusions derived from them. But a very violent effort is requisite to change our judgment of manners, and excite sentiments of approbation or blame, love or hatred, different from those to which the mind from long custom has been familiarized. And where a man is confident of the rectitude of that moral standard by which he judges, he is justly jealous of it, and will not pervert the sentiments of his heart for a moment in complaisance to any writer whatsoever. (Reference Hume1985/1758, 247)

This passage is often referred to as being the first observation of imaginative resistance. However, the phenomenon to which Hume calls attention is, in the first instance, slightly different from what is normally called imaginative resistance in the literature. This will be of importance for the account of imaginative resistance that I will offer here. What Hume observes is that a reader refuses to adjust his sentiments “of approbation and or blame, love and hatred” to the will of the author in the same way as he will adjust to “speculative” (i.e., descriptive) errors. To illustrate what I think Hume has in mind: we willingly suspend our beliefs when engaging with fictions—we accept that there are hobbits in the story even though we believe that there are in fact no hobbits in reality—whereas we tend not to suspend our affective comportments in the same way. Someone who genuinely disapproves of, for example, infanticide will not suspend her disapproval, or at least not do so as easily, when engaging with a fiction. Similarly, someone who adores the way a sunset looks in the actual world will not feel differently about fictional sunsets, assuming that they look the same in non-evaluative respects.Footnote 5

This remark by Hume provides the inspiration for the sensibilist diagnosis of imaginative resistance offered in this article. On this diagnosis, we refuse to accept alternative evaluative truths in fictions because we do not suspend our sentiments in the same way as we suspend of beliefs when engaging with fictions, and, importantly, these sentiments are what dictates the extension of evaluative predicates. The latter notion, that evaluative terms have their extensions fixed by our sentiments, is what I will refer to as sensibilism in this article.

Sensibilism, so defined, is a form of metaethical nonfactualism, in that it postulates that moral and, more generally, evaluative facts are dependent on the perspective from which we perceive them. What falls under an evaluative concept is determined by our feelings and attitudes. This runs counter to influential objectivist theories within metaethics, according to which moral facts are independent of the perspectives from which we perceive them. Naturally, it lies beyond the scope of this article to provide general motivations for nonfactualism about evaluative terms. Let me instead point to some benefits of the current approach, which should serve to justify it despite the reliance on controversial assumptions. First, notwithstanding the fact that the alethic puzzle of imaginative resistance is a phenomenon that concerns evaluative language in the special way explained in the previous section, only limited attention has been paid to it by metaethicists and theorists of the semantics of evaluative terms.Footnote 6 The current approach can therefore serve a as bridge between discussions about the nature of the evaluative in aesthetics, metaethics, and the philosophy of language.

Secondly, it has been suggested that theorists who subscribe to nonfactualist views of the semantics of evaluative terms are in a worse position than realists in accounting for imaginative resistance. Indeed, Samuel Cain Todd even goes as far as to claim that the phenomenon as such arises, at least partly, because of the metanormative realist commitments of people engaging in the debate (Todd Reference Todd2009; cf. Stojanovic Reference Stojanovic, McPherson and Plunkett2017, 122). In relation to such claims, this paper serves as an important demonstration that nonfactualist outlooks by no means lack the resources to explain the phenomenon.

Thirdly, and most importantly, as explained in section 4, the approach has several explanatory advantages over competing views, which should serve to motivate it on independent grounds despite controversial assumptions.

Such is the general motivation for the current approach. In what follows, I develop in some detail what a sensibilist theory of evaluative contents can look like, after which I go on to describe how it accounts for imaginative resistance. Sensibilism, as defined here, is the family of views which take the extension of evaluative properties to be determined by our attitudes, and which, furthermore, take this to be built into the meaning of evaluative language. Recently, sensibilism, restricted to evaluative gustatory terms, has been developed in discussions centred on predicates of personal taste. A natural and often invoked idea within this literature is that the extension of, for instance, “tasty” is somehow determined by which things we appreciate the taste of. In essence, a thing is tasty if we like how it tastes. Formally, this view is implemented as an extension of the possible worlds’ framework for contents. In this framework, the contents of sentences are taken to be the set of possible worlds in which the sentence is true. On an extension of this framework, the content of a sentence in context is taken to be the set of world-taste pairs in which the sentence is true. A “taste” is, in this framework, akin to the notion of a possible world. Just as a possible world is maximally decided in the sense that all facts are settled in it, so a “taste” is maximally decided in the sense that it provides a verdict about every object regarding whether it is tasty or not. According to this view, the truth conditions of taste-sentences look like something along the following lines:

In this notation, the double brackets represent a function that maps an expression to its semantic value. Since we are talking about sentences, this is either truth or falsity. The c denotes the context of utterance and the angle brackets the points of evaluation against which the sentence is evaluated for truth and falsity. This is, of course, incomplete as it stands. We are not told which world or taste is relevant for determining the truth of the sentence. While the world can, by default, be assumed to be the world of the context of utterance, i.e., the actual world, which taste—g in the notation above—is relevant is a substantial question. As it stands, these skeletal truth conditions are compatible with a variety of answers to this question, and therefore with a variety of views on the nature of taste-predicates. A subjectivist will claim that it is invariably the speaker’s taste that is relevant for determining the truth of a taste-sentence in a context; a relativist that it is the taste of the assessor (potentially the speaker herself). As noted by MacFarlane, the semantics above is also compatible with a version of expressivism (Reference MacFarlane2014, 167–72). In MacFarlane’s terminology, this semantics is compatible with several different “post-semantics,” i.e., different ways of specifying what is asserted (or expressed) by a taste-statement. In essence, the post-semantics tells us whose taste is relevant for settling the truth and falsity of a taste statement—the speaker’s, an assessor’s or someone else’s. All the abovementioned views fit sensibilism as characterised above, as they make tastiness sensitive to our noncognitive reactions. They all capture the idea that what is tasty is determined by our affective responses in one way or the other.

For clarity, I will assume a relativist post-semantics when spelling out how this semantics accounts for imaginative resistance. However, it should be emphasised that my account does not hinge on this particular assumption. Expressivist or subjectivist post-semantics could offer a similar explanation of imaginative resistance.

Next, we need to take the controversial step to generalise this semantics to other evaluative terms. To do so, we adopt the sensibilist assumption that other evaluative matters are settled by affective responses, similar to how one settles the question of whether something is tasty by deciding whether one likes its taste. If this assumption is granted, the framework outlined above can easily be extended to include all evaluative discourse. I am going to term the extension of gustatory tastes in MacFarlane’s sense to include maximally decided verdicts about cruelty, beauty, goodness, etc. “sensibilities,” and to accordingly take the semantic values of sentences to be the sets of pairs of worlds and sensibilities in which the statement is true:

3. Explaining imaginative resistance

In this section, I adopt a relativist interpretation of the semantics outlined above and discuss how it, together with some standard assumptions about fictional discourse, explains imaginative resistance.

The generic feature of sensibilism is that sentences have what we call a sensibility-index in their point of evaluation. All sentences are evaluated for truth and falsity not only against the state of affairs of the actual world or a (set of) possible world(s), but also against affective proclivities (for purely descriptive sentences, this will not change their truth-conditions). But in order to know the circumstances under which some particular statement is true, we need to know which world and whose sensibility is relevant for settling this. This is the job of the “post-semantics” in MacFarlane’s terminology. Following MacFarlane regarding “tasty,” we can specify a relativistic way of developing sensibilism about evaluative discourse.

Relativist post-semantics: A sentence S is true as used in a context c 1 and assessed from context c 2 iff S is true at c 1, ⟨w c1, s c2⟩, where w c1 is the world of c 1 and s c2 is the sensibility of the assessor. (cf. MacFarlane Reference MacFarlane2014, 67, 151ff)

This proposal makes it the case that evaluative statements are not true and false in a context simpliciter, but rather true-in-a-context-of-use-as-assessed-from-a-perspective. For instance, the truth-value of the statement:

will not only depend on the context of use—that is, what sunsets look like in the world in which the sentence is used—but also how the assessor of the sentence, in my own case I myself, finds sunsets. Since I do indeed have the requisite positive experience when looking at a sunset, the sentence is true. From the perspective of someone who does not have this kind of positive experience when watching the sun set, the sentence is false. The same proposition is, on the relativist view, capable of being true as assessed from one person’s perspective, and false when assessed from another’s. It is important to distinguish this kind of relativity from the one obtained by building the assessed perspective into a content: this form of relativism does not maintain that the asserted content of (3) is that sunsets are beautiful to me (whoever asserts the sentence). The latter is something that even a militant sunset hater should agree is true when that sentence is asserted by me.

Now let us consider fiction. On the orthodox approach to fictional discourse, we think of a fiction as determining a set of worlds (Lewis Reference Lewis1978). Intuitively, this is the set of worlds where things are as described by the fiction.Footnote 8 Statements about the fiction, for instance:

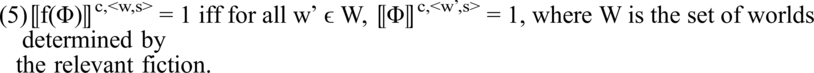

are, on this approach, taken to contain a hidden intensional operator along the lines of “in the worlds of the Sherlock Holmes stories,” which switches the world of the evaluation of (4) from the actual world to the set of worlds determined by the fiction. On a skeletal version of the truth conditions for this operator, “f”, augmented with the sensibility-index, it states that:

Thus (4) is true, since in the worlds of the Sherlock Holmes stories he did indeed live on Baker Street. Notice that W is a set of worlds. This is because many things are left indeterminate by a fiction, for instance the colour of Watson’s eyes. W thus contains worlds in which he has blue eyes and worlds in which he has green eyes. For it to be true that Watson’s eyes are green, it has to be true in all the worlds in this set; for it to be false that Watson has green eyes, it has to be false across all these worlds. (5) is furthermore silent on how to deal with states of affairs that are left unmentioned by the narrative, but which are, nonetheless, intuitively true in it—for instance, that the Earth is round in the Sherlock Holmes stories. I will put this issue aside in the present context.

With this background, let’s look at a case of imaginative resistance:

Death on a Freeway

Jack and Jill were arguing again. This was not in itself unusual, but this time they were standing in the fast lane of I-95 having their argument. This was causing traffic to bank up a bit. It wasn’t significantly worse than normally happened around Providence, not that you could have told that from the reactions of passing motorists. They were convinced that Jack and Jill, and not the volume of traffic, were the primary causes of the slowdown. They all forgot how bad traffic normally is along there. When Craig saw that the cause of the back up had been Jack and Jill, he took his gun out of the glovebox and shot them. People then started driving over their bodies, and while the new speed hump caused some people to slow down a bit, mostly traffic returned to its normal speed. So Craig did the right thing, because Jack and Jill should have taken their argument somewhere else where they wouldn’t get in anyone’s way. (Weatherson Reference Weatherson2004, 1)

In this vignette, what causes the trouble is the very last sentence. Even though this claim is explicitly part of the story, we feel that it is not up to Weatherson, or whoever else narrates the story, to decide that the action was right. We refuse to go along, so we take:

to be false, even though the author claims that it is true in the fiction. This is the alethic puzzle of imaginative resistance.

We are now in a position to account for this. With this semantics for evaluative terms, we no longer speak of truth-in-a-world, but rather of truth-in-a-world-sensibility-pair.Footnote 9 (6) is a statement about a fiction and, as such, prefixed with an implicit fiction-operator, which switches the world of evaluation from the actual world to the worlds determined by the fiction. Importantly, the sensibility-index is not switched by this operator, but remains the same. Every world determined by the fiction will be coupled with the assessor’s actual sensibility. According to none of these world-sensibility pairs will (6) be true, since it is the attitudes we have in the actual world which are relevant for settling the extension of evaluative predicates in the fictional worlds. This is the heart of the account offered here.

It’s probably wise to be as clear as possible concerning how Hume’s observation interacts with the sensibilist semantics in this account. The observation we took from Hume, remember, was that there is an asymmetry in how cognitive and noncognitive attitudes interact with fictions. We willingly suspend our beliefs when engaging with fictions, whereas we do not suspend such sentiments as approval and disapproval. However, this observation by its own would not account for the alethic puzzle. To see why, consider a fiction in which the author stipulates that a massacre of hundreds of children takes place. We would certainly disapprove of such actions, but would not at all be tempted to deny that it is true in the fiction that they do take place. That we disapprove of something does not make us unwilling to accept it as a fact of the fiction.

On the current account, the difference between this case and the evaluative case is that the extensions of evaluative predicates are dictated by our attitudes, whereas this does not go for the predicates outlining that a massacre takes place. The assumption that the relevant sentiments, as a matter of conceptual necessity, fixes the extension of evaluative predicates is needed to explain that we refuse to accept that, for instance, Craig did the right thing in the fiction. Without the sensibilist assumption, there would be no reason why we would not accept diverging evaluative frameworks in fictions, even though these do not accord with our own sentiments. To address for the alethic puzzle of imaginative resistance, one needs to account for the intimate connection between the truth-value of evaluative statements, in particular, and our sentiments. This is done by the sensibilist semantics.

This account of imaginative resistance sits well with an observation made by Gendler concerning the alethic puzzle. Gendler, following Walton (Reference Walton1994), considers a fiction where the following sentence occurs:

Gendler observes that while our initial reaction to such a fiction is one of perplexity, we can accommodate it by a manoeuvre which she calls “doubling of the narrator”:

Our first instinct—at least my and Walton’s first instinct—is to reject the invitation to make-believe that “It was right for Giselda to kill her baby, given that it was a girl.” My inclination is to respond to the invitation with something like the following: “What is right to make-believe is that according to the narrator who is telling the story, female infanticide is morally acceptable. But even in the world of the story, the narrator is wrong; infanticide is not morally acceptable, even in a society where everyone believes that it is.” (2000, 63)

I share Gendler’s reaction that we can make sense of (7) by taking it to represent the view of some (perhaps fictional) narrator. Alternatively, we may take it to simply reflect the moral view of the actual author of the story. On the current account, such examples are naturally diagnosed as similar to exocentric readings of predicates of personal taste (see for instance Lasersohn [Reference Lasersohn2005]). These are cases where a speaker uses a taste predicate in such a way that it is naturally interpreted to concern someone else’s taste, rather than their own. For instance, when watching a cat eating some cat food, one can say:

In the described context, (8) is naturally taken to intend to communicate that the cat likes the cat food, rather than that the speaker does. Cases like (8) show that despite the fact that there is a strong default tendency to take “tasty” as relating to the speaker or assessor’s sensibilities, there are special cases in which we interpret them as relating to someone else’s. As Gendler describes, our initial reaction to (7) is to reject it since it does not accord with our own sensibilities. However, under some circumstances we might be able to reach for an exocentric reading, where the relevant sensibility for determining the truth-value of the statement is not our own, but rather that of, for instance, the narrator. What we get in such circumstances is a reading of (7) on which it is true, simply because it corresponds to the way the narrator thinks about the matter, similar to how we can get a true reading of (8) in the described circumstances, since it corresponds to the way that the cat feels about the cat food. Where such exocentric readings are available, we will not experience imaginative resistance.

Another notable feature of the current view is that the above account does not intrinsically rely on the worlds of the fiction being possible. In recent years, it has become increasingly common to rely on the notion of impossible worlds to account for, among other things, counterfactual conditionals with impossible antecedents and, notably, impossible fictions (see Berto [Reference Berto and Zalta2013] for an overview). The given account of imaginative resistance is compatible with such approaches. Even if fictions involve impossible worlds, this does not change the fact that when traveling in our imagination to such impossible worlds, we take our actual feelings and attitudes with us. Thus, even in these exotic places of twenty-first century modal semantics, it is our actual feelings and attitudes that settle the extension of evaluative terms and concepts.

This concludes the sensibilist account of imaginative resistance. For the purpose of making the exposition transparent, let me again emphasise that nothing in particular hangs on the relativist post-semantics we adopted. What does the work on this account is (1) Hume’s observation that to a certain extent we bracket our beliefs when engaging with fictions, whereas noncognitive reactions are not bracketed in the same way, and (2) the sensibilist semantics of evaluative sentence, according to which these are evaluated for truth and falsity not only with respect to worlds, but also to sensibilities. Again, subjectivist and expressivist positions can avail themselves of the same resources and, therefore, the same diagnosis of imaginative resistance.

4. Other proposals

In this section, I compare the sensibilist explanation of imaginative resistance to some prominent alternatives. I argue that the current approach has some distinct advantages over these competitors.

First, it has been suggested that imaginative resistance might be explained by our inability to imagine conceptually impossible scenarios and make such scenarios true in fiction (Walton Reference Walton1994). But, as has been pointed out, it seems that we often do imagine conceptually impossible scenarios and that we can readily accept them as true in fictions. I will not expand on this point here, since this has been discussed extensively by, among others, Gendler (Reference Gendler2000).

Let me instead add to this criticism that the assumption that substantial normative views are ruled out by the very meaning of normative terms runs counter to very commonly held views within metaethics, going back to G. E. Moore’s open question-argument (Reference Moore1903). As Sharon Street puts it:

[…] as a purely conceptual matter […] normative truths might be anything. In other words, for all our bare normative concepts tell us, survival might be bad, our children’s lives might be worthless, and the fact that someone has helped us might be a reason to hurt that person in return. (Reference Street2008, 208)Footnote 10

In relation to this, it is an interesting and often overlooked feature of imaginative resistance that the evaluative cases which trigger resistance need not be absurd. The moral views endorsed by some people as actually true will be resisted by others as not even being true in a fiction where the author tries to stipulate them as such. For instance, a fiction describing Nelson Mandela’s life in which it is declared that the fight against apartheid was morally reprehensible would surely trigger imaginative resistance (for us). Yet many people believed and still believe that it was morally reprehensible. While highly deplorable, it does not seem like such people need to be subject to linguistic confusion.Footnote 11

This kind of example also constitutes a problem for a proposal by Kathleen Stock, according to which imaginative resistance with moral cases (Stock only discusses moral cases) is due to the fact that we don’t understand the proposition in question (Reference Stock2005).Footnote 12 Again, a novel in which the struggle against apartheid is declared to be morally reprehensible in the fiction would surely trigger imaginative resistance. Yet, it is not as if the worldview reflected in such a fiction is incomprehensible. Presumably, even a nonracist scholar of apartheid who has written several books on the subject would refuse to accept racists ideas as fictionally true.Footnote 13

Another suggested explanation of the phenomenon is based on how we sometimes “export” things that are described as true in the fiction and take them to be true in the actual world. Gendler suggests that cases that evoke genuine imaginative resistance will be cases where the reader feels that she is “being asked to export a way of looking at the actual world which she does not wish to add to her conceptual repertoire” (Reference Gendler2000, 77).

On this view, imaginative resistance would arise because accepting the diverging evaluative statements as true in fiction would make us change our view about what is right and wrong in the actual world. The question is why we would be especially inclined to export evaluative truths from the fiction to the actual world. Gendler’s answer is that this is because (i) moral laws (she only discusses the moral case) are true in all possible worlds and (ii) there are moral disagreements in the actual world.Footnote 14

The problem with this explanation is that it predicts cases of imaginative resistance where there are none. Take any question the answer to which is disputed in the actual world and where the correct answer, whatever it is, will also be a necessary truth. Gendler’s diagnosis predicts that it will give rise to imaginative resistance. But this prediction is not borne out. Consider the issue of what constitutes personal identity. There is widespread disagreement on what constitutes personal identity and whatever the answer to that question, it is presumably a necessary truth. Now, take a fiction in which personhood is essentially connected to an immaterial substance like the soul, such as Dante’s Inferno. I have no inclination whatsoever to deny that it is true in the story that humans are identical to their immaterial soul even though I myself believe that human persons are identical to their living human bodies. If Gendler’s two conditions for imaginative resistance were sufficient, Inferno would trigger imaginative resistance for anyone with a sufficiently divergent view of human personhood. It does not.

This indicates that the two conditions for imaginative resistance offered by Gendler are not sufficient. Something needs to be added. At some points, Gendler speaks about moral truths being special in that they are perspectival (2000, 74; cf. also Gendler Reference Gendler and Nicols2006). Perhaps Gendler would want to say that what distinguishes moral issues, which give rise to imaginative resistance, from other necessary-but-disputed cases like personal identity, which do not, is that they are perspectival. If this is indeed the case, the current explanation is actually quite close to that offered by Gendler. It could perhaps even be taken as giving a semantic gloss to the “perspectiviality” of evaluative discourse, and to specify precisely how that helps to explain imaginative resistance.

The example with personal identity can also be brought to bear against a proposal by Weatherson, according to which imaginative resistance is not limited to the evaluative, but rather pertains to any case in which a being F is grounded in some lower level facts:

In general, if whether or not something is an F is determined in part by “lower-level” features, such as the shape and organisation of its parts, and the story specifies that the lower-level features are incompatible with the object’s being an F, then it is not an F in the fiction. (Weatherson Reference Weatherson2004, 6)

This account faces similar issues as those raised with respect to Gendler. Again, I am inclined to believe that my living body, without any soul or psychology, would still be a human person. On an animalistic view of what constitutes personhood, the lower level fact that a is a material object with such-and-such chemistry determines that a is a living human body (let us suppose), and therefore also a human person. However, I have no trouble accepting a fiction in which the fact that a is a human person is instead grounded in facts about immaterial substances. As with Gendler’s (on one interpretation), Weatherson’s explanation predicts that there should be resistance where there is none.Footnote 15

Stephen Yablo’s account of imaginative resistance is the one proposal currently on the table that most resembles our own. Yablo thinks that the phenomenon specifically arises with “grokking” concepts. These are concepts which identify their object though specific kinds of experiences. Here is how Yablo takes this to be connected to imaginative resistance:

It’s a feature of grokking concepts that their extension in a situation depends on how the situation does or would strike us. “Does or would strike us” as we are: how we are represented as reacting, or invited to react, has nothing to do with it. Resistance is the natural consequence. If we insist on judging the extension ourselves, it stands to reason that any seeming intelligence coming from elsewhere is automatically suspect. This applies in particular to being “told” about the extension by an as‐if knowledgeable narrator. (Yablo Reference Yablo2008, 145)

On one reading of this passage, Yablo takes grokking concepts to be such that our reactions determine their extension. On this reading, the explanation of imaginative resistance that Yablo offers seems similar to the current explanation. The above account can, in this case, be read as offering a semantic framework for grokking concepts, and a way of developing Yablo’s cursory remarks on the subject.

However, other passages speak against this interpretation of Yablo. Earlier in the same text, Yablo identifies “oval” as a grokking concept and contrasts it with “irksome,” which he takes to be response-dependent (in a nonrigidified way). He writes:

Our responses do not track the extension of “irksome”; they dictate it. It makes no sense to suggest that our tendency to be irked by various things might not have been, or might have turned out not to be, a good guide to what is really irksome. It is different with “oval.” Our responses give us access to the extension of “oval,” but they do not dictate the extension. (Yablo Reference Yablo2008, 127)

This passage, as well as others, suggests that Yablo does not take grokking concepts to have their extension determined by our actual reaction, but that our reactions instead uncover these.

On this alternative gloss of what grokkingness amounts to, it is less clear to me what explanatory weight it carries in relation to imaginative resistance. It is easy to see why there is a limit to the author’s authority over evaluative truths in her fiction if the extension of evaluative predicates is determined by our reactions in the actual world. But if our reactions are just a privileged, albeit defeasible, mode of access to the extension of evaluative predicates, what prevents the author from tampering with these extensions in nonactual worlds? There seems to be an explanatory lacuna in the appeal to a concept’s grokkingness to explain imaginative resistance when grokkingness is understood in this way.

5. Nonevaluative cases

The kind of explanation I have offered targets the evaluative cases of imaginative resistance in particular. However, as I argue below, this explanation is compatible with treating a certain class of nonevaluative cases in the same way. In contrast, some nonevaluative cases that have been claimed to be similar to the evaluative ones are not susceptible to my proposal. In the following, I argue that this is not a problem for the current view since these cases are relevantly dissimilar from the evaluative ones. First, consider a nonevaluative case presented by Weatherson:

Cats and Dogs

Rhodisland is much like a part of the actual world but with a surprising difference. Although they use the word “cat” in all the circumstances when we would (i.e., when they want to say something about cats), and the word “dog” in all the circumstances we would, in their language “cat” means dog and “dog” means cat. None of the Rhodislanders are aware of this, so they frequently say false things when asked about cats and dogs. Indeed, no one has ever known that their words had this meaning, and they would probably investigate just how this came to be in some detail, if they knew it were true. (Weatherson Reference Weatherson2004, 4)

If this was an instance of imaginative resistance that required the same explanation as the evaluative cases, it would constitute a problem for the current proposal. There is no plausible extension of my explanation to cases like this. However, I do not think that this case is very similar to the evaluative ones. Firstly, while the story is indeed strange and perhaps difficult to imagine, it is not clear that the author has failed to make this scenario true in the fiction. At least this is not salient in the way that it is in evaluative cases. This assessment is supported by the empirical study mentioned in the beginning of this paper, which registers that even for nonevaluative cases that are as hard to imagine as the relevant evaluative cases, there is still a difference regarding the extent to which the subjects think that the claims are true in the fiction (Kim, Kneer, and Stuart Reference Kim, Kneer, Stuart, Cova and Réhault2018). Secondly, there are other differences from the evaluative cases. The phenomenon described by Gendler—that we are inclined to take evaluative fiction to reflect the actual views of the narrator—does not show up at all in this case. Moreover, the objection raised against Stock’s account in terms of understandability is also relevant. The nonevaluative case above is absurd; no one has actually held something close to what we are supposed to imagine as their actual view. While this might also be true of the evaluative cases discussed by Weatherson, it is not essential to such cases. Again, think about the Nelson Mandela case outlined above. Nonevaluative cases which have this feature of being believable in the sense of being taken as actual by some, whereas not even being taken as true in a fiction for others, are hard to come by. Taken together, these differences put pressure on the view that nonevaluative cases of fictions that are hard to imagine in general should be explained in the same way as the evaluative cases of imaginative resistance.

Having said this, it should be noted that the current view is compatible with there being nonevaluative cases of imaginative resistance which should be diagnosed in the same way as evaluative cases. Take, for instance, a fiction that describes the ending of the movie Titanic as not being sad. Plausibly, we would refuse to go along with this (as long as we take the movie to end in the same way as in the actual world). Yet, it could be maintained that “sad” in the relevant sense in which the term applies to movies is not an evaluative predicate since it does not communicate something positive or negative about the movie. Bad movies can have sad endings.

This is a nonevaluative case to which the current proposal is plausibly extendable. While not being evaluative, “sad” in the relevant sense is a paradigm case where the extension of the term is naturally thought to be tied to our noncognitive reactions, just as the current proposal suggests is the case with evaluative terms. This raises the question of which resources the current account has to explain what it is that makes a term like “beautiful” evaluative and a term like “sad” (in the relevant sense) nonevaluative, given that they have isomorphic semantics. A natural answer to this question from within the current framework is that it depends on the valence of the noncognitive experience to which the extension of the concept is tied. The noncognitive reaction tied to the relevant sense of “sad” is not intrinsically positive or negative, whereas the noncognitive experience tied to “beautiful” is intrinsically positive. It is a plausible working hypothesis that this is what distinguishes evaluative terms from nonevaluative yet sensibilist terms like “sad.”

6. Deviant cases

Up to this point, I have proceeded under the assumption that it is impossible for an author to make an alternative evaluative scenario true in a fiction. However, some recent literature has questioned whether this really is the case. For instance, it has been suggested that the genre of a fiction might affect how prone we are to comply with alternative evaluative truths (Liao, Strohminger, and Sripada Reference Liao, Strohminger and Sripada2014). In Liao et al.’s empirical study, they confront their subject with two vignettes, one of which reads as follows:

The Story of Hippolytus and Larissa

Hippolytus fell in love with Larissa. Out of his love for her, he played a trick on her by giving her a mint leaf to eat. Unaware of the consequences, Larissa proceeded to consume the leaf. Little did she know that this mint leaf was special. Consuming this special leaf would bind her to be with him for the rest of eternity. When Larissa’s mother found out what Hippolytus had done, she appealed to Zeus to get her daughter back. But Zeus declared Hippolytus’s action to be just, and that Larissa indeed must fulfil her obligations. And that was how Larissa came to be the wife of Hippolytus.

The study finds that those participants who considered themselves familiar with Greek mythology were more prone to accept it is as true in the fiction that Hippolytus’s actions are morally right. They interpret this result as support for the notion that imaginative resistance might be dependent on genre: people are less prone to experience imaginative resistance if they take themselves to be engaging with a genre where moral deviancies, in the relevant sense, are to be expected.Footnote 16

Are these results compatible with the sensibilist account of imaginative resistance? I think so. First, let us again consider so-called “exocentric” readings of evaluative predicates, discussed in section 3. On a sensibilist-friendly interpretation of these results, the participants who report that it is true in the fiction that Hippolytus’s actions were morally right do so because they manage to access an exocentric reading: they take “morally right” to be implicitly indexed to Zeus’s proclivities, rather than to their own. As mentioned, in Liao et al.’s study, participants who consider themselves to be highly familiar with Greek mythology are more prone to accept that Hippolytus did the right thing. One can conjecture that this is due to the fact that those who are familiar with the hierarchies of the ancient Greek pantheon are more prone to take Zeus’s inclinations to be the most relevant for interpreting a statement to the effect that something is right (somewhat similar to what the cat thinks about the cat food seems to be of most relevance in the context in which [8] is interpreted).

But perhaps there are reasons to think that the case above is different from standard cases of exocentric readings: it is not just that some people evaluate the statement that Hippolytus’s actions are right from Zeus’s perspective instead of their own. Zeus makes Hippolytus’s actions right. This, it could be argued, makes the case disanalogous to standard examples of exocentric readings.

But even if one would be reluctant to outright assimilate this example to exocentric readings, the general point still stands: even if there is a strong tendency to assess evaluative statements against our actual sensibilites, as postulated by sensibilism, it is not surprising that there are exceptional cases where the link between one’s sensibilites and one’s evaluative judgement is severed, as, for instance, in the contexts of fictions which contain explicit elements of divine command theory. Having said this, it should be granted if there is a widespread tendency to dislocate evaluative truths from our actual sensibilities, that would speak against the diagnosis offered here, which turns on there being a strong default tendency to hold them fixed to how we actually feel.

Another, and perhaps more interesting, kind of exception from the current theory’s point of view would be if there are cases where fictions manage to temporally change our actual sensibilities and, for instance, by doing so, makes us condone actions which we would otherwise find outrageous. The difference from the kind of “exocentric” cases discussed before would be that we would judge with our actual attitudes in such cases, but that these, because of the working of the fiction, would be momentarily different from our normal affective proclivities. Elisabeth Camp (Reference Camp2017) has argued that there are such cases and mentions Nabokov’s Lolita as an example. The idea is that in our interaction with Nabokov’s novel we would temporarily pardon the main character, the pedophile Humbert Humbert’s, actions.

I am not convinced that this is what really goes on when we engage with antiheroes such as Humbert Humbert. On the contrary, it seems to me that part of the powerful aesthetic effect this novel produces in us has to do with us not condoning Humbert Humbert’s actions (cf. Eaton Reference Eaton2012). But this is a complicated issue and I do not wish to wed the current theory to any specific view of it. If there are cases of this kind, I do not think it would speak against my proposal. Imaginative resistance would still be predicated to arise whenever a fiction fails to achieve this kind of temporary change to our actual attitudes.

7. Conclusion

I have discussed the issue of why we refuse to go along with fictions where alternative evaluative scenarios are described. The core of my proposal is that the extension of evaluative predicates is relative to how we feel about things and, while fictional contexts serve to displace the world against which a statement is evaluated for truth and falsity, the sensibilites against which they are evaluated are one’s actual ones. This proposal, it has been argued, has several explanatory advantages over competing views, and also goes to show that nonfactualist views about the evaluative are in a good position to account for this phenomenon. Standard assumptions about the nature of fictional discourse in combination with the nonfactualist semantics for evaluative terms presented here make accurate predications concerning imaginative resistance.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this article have been presented at the March 2018 Doc’in Nicod session at the Institute Jean Nicod, École Normale Supérieure, The Future of Normativity Conference at the University of Kent in June 2018, the 11th Arché Graduate Conference at the University of St. Andrews in October 2018, the higher seminar in aesthetics at the University of Uppsala in December 2018, and the Stockholm June Workshop 2019 at the University of Stockholm. For helpful comments and advice, I am grateful to the participants of these events, as well as to Karl Bergman, Stina Björkholm, Gunnar Björnsson, Matti Eklund, Maria Forsberg, Pekka Väyrynen, Olle Risberg, Henrik Rydéhn, Isidora Stojanovic, Andreas Stokke, Nick Wiltsher and two anonymous referees for this journal.

Funding statement

Part of this research has been generously funded by the Swedish Research Council, grant number 0219-02905, and by the Alexander von Humboldt foundation.

Nils Franzén (PhD, Uppsala University) is a postdoctoral researcher at the Institut für Philosophie at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin and a researcher at the department of philosophy at Uppsala University. He works primarily within the philosophy of language, metaethics, and aesthetics.