Leo Tolstoy’s novels War and Peace (1869) and Anna Karenina (1873–1877) are generally considered to be among the greatest works of fiction ever written. Transcending his bereft childhood and disturbed adolescence, Tolstoy became a world-famous writer, and in later years a guru-like pacifist, anarchist, vegetarian and critic of the Russian Orthodox Church – influencing, among others, Gandhi and Martin Luther King.Footnote a

Tolstoy was born in 1828 on the family estate of Yasnaya Polyana south of Moscow, the youngest of four boys. He was orphaned early: his mother, Princess Maria Volkonskaya, died when he was 2, his father, Count Nicolai, when he was 9. He and his brothers were then sent 500 miles away to his aunt’s estate in Kazan. Described by his teachers as ‘unable and unwilling to learn’ (Reference WilsonWilson 1988), he dropped out of university (Fig. 1). There followed a phase of alcohol-fuelled gambling, womanising and failed farming. At his brother’s suggestion, in 1851 he became an army officer, and while serving in the Caucasus and later in the Crimean War, he discovered his vocation as a writer. His autobiographical trilogy Childhood (1852), Boyhood (1854) and Youth (1857) were an instant success. He left the army, settled on the family estate, liberated his serfs and, in 1862, married Sophia Behrs, 16 years his junior.

FIG 1 Tolstoy aged 20, in 1849. Two year earlier he had left university without a degree.

The marriage was initially happy. Sophia became his amanuensis, rewriting War and Peace seven times for Leo. They had 13 children. However, with Tolstoy’s increasing fame, accumulated disciples and hangers-on, and eccentric views (e.g. on marital celibacy – a precept he signally failed to practise!) the marriage deteriorated, often into open warfare, and was beset by Sophia’s suicide threats (Fig 2). At the age of 82, possibly in the early stages of a confusional state, Tolstoy precipitously left home, accompanied by his daughter Alexandra. A day later he died of pneumonia at Astapovo railway station en route to the Caucasus.

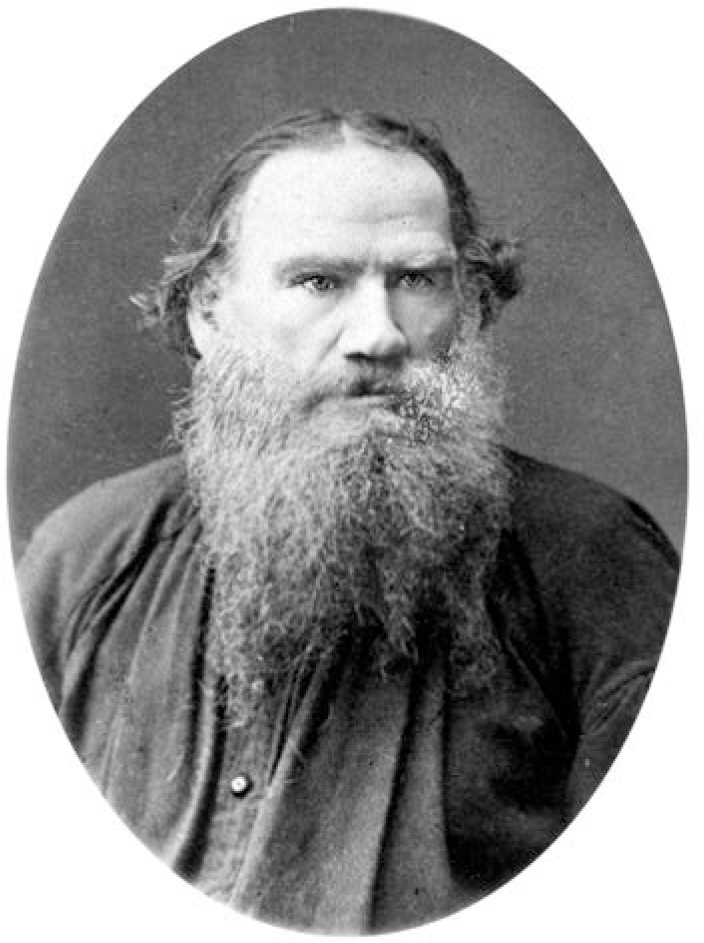

FIG 2 Tolstoy in his mid-fifties.

War and Peace

I seem to re-read War and Peace roughly every 20 years – my fourth cycle is fast approaching. Psychiatrists will learn as much or more from it than from any psychiatric tome (Reference HolmesHolmes 2014a,Reference Holmesb). Tolstoy’s capacity to capture the interpenetration of historical events with family and individual psychology, all within the confines of a novelistic love story is, Shakespeare excepted, unrivalled in the Western canon.

Here I focus on three interconnected aspects emerging from one short passage, relevant to everyday mental health work. First, it vividly depicts the sudden emergence of hope in the midst of grief and depression; second, it illustrates how recovery entails enhancement of connectedness, not just to intimate others, but also to nature and the wider ecology; third, it provides the chastening thought that for most people, under most circumstances, getting better occurs ‘naturally’ through the flux of life, rather than thanks to any species of psychological or psychiatric help. Nevertheless, the passage I have chosen is a beautiful example of the kind of outcome one strives for in psychotherapy.

The oak tree sequence

The oak tree sequence comes at the beginning of Part 3. Prince Andrei is a rich, handsome, intelligent man in his early 30s, highly capable, but bored, depressed, self-preoccupied and disillusioned – perhaps not unlike aspects of Tolstoy himself (the novel’s contrasting protagonist, Pierre, embodies the author’s gauche, searching, spiritually deprived self).

Andrei’s mother is dead and he shares his household with his sister and domineering father. His wife – whom he did not love – has recently died in childbirth, leaving him with a young son.

It is early spring. Andrei is making a journey to inspect one of his many estates.

‘At the edge of the road stood an oak […]. It was an enormous tree, double a man’s span, with ancient scars where branches had long ago been lopped off and bark stripped away. With huge ungainly limbs sprawling unsymmetrically, with gnarled hands and fingers, it stood, an aged monster, angry and scornful, among the smiling birch trees. This oak alone refused to yield to the season’s spell, spurning both spring and sunshine.

“Spring, and love, and happiness!” this oak seemed to say, “Are you not weary of the same stupid meaningless tale? […] I have no faith in your hopes and illusions” […] there were flowers and grass under the oak too, but it stood among them scowling, rigid, misshapen and grim as ever.

“Yes, the oak is right, a thousand times right”, mused Prince Andrei. “Others – the young – may be caught anew by this delusion but we know what life is – our life is finished!” ’ (Reference TolstoyTolstoy 1978 reprint: p. 492).

Prince Andrei is required by protocol to stay the night with a local grandee, Count Rostov. As he approaches the Rostov mansion he catches sight of a young girl, Natasha Rostov – pretty, playful, laughing, carefree:

‘ “that slim pretty girl did not know or care to know of his existence […]. What is she thinking of? Why is she so happy?” Prince Andrei asked himself with instinctive curiosity’ (p. 493).

In his bedroom after dinner, Prince Andrei throws open his window and eavesdrops on Natasha and her cousin Sonia eulogising the balmy summer evening:

‘Two girlish voices broke into a snatch of a song […].

“Oh it’s exquisite! Well, now let’s say good night and go to sleep.”

“Sonya Sonya! […] Oh, how can you sleep? Just look how lovely it is! Oh how glorious! Do wake up Sonya!” and there were almost tears in the voice. “There never, never was such an exquisite night […]. I feel like squatting down on my heels, putting my arms round my knees like this tight – as tight as can be – and flying away! Like this […].”

“And for her I might as well not exist!” thought Prince Andrei […] for some reason hoping yet dreading she might say something about him […].

All at once such an unexpected turmoil of youthful thoughts and hopes, contrary to the whole tenor of his life, surged up in his heart’ (p. 495).

Prince Andrei leaves early the next morning. Later, on his way home he catches sight of the old oak. It is a wonderful day:

‘Everything was in blossom, the nightingales trilled and caroled, now near, now far away […]. The old oak, quite transfigured, spread out a canopy of dark sappy green, and seemed to swoon and sway in the rays of the evening sun. There was nothing to be seen now of knotted fingers and scars, or old doubts and sorrows. Through the rough century-old bark, even where there were no twigs, leaves had sprouted, so juicy, so young it was hard to believe that aged veteran had born them.

“Yes it is the same oak” thought Prince Andrei, and all once he was seized by an irrational, springlike feeling of joy and renewal […].

“No, life is not over at thirty-one”, Prince Andrei decided all at once, finally and irrevocably. “It is not enough for me to know what I have in me – everyone must know it too […] that young girl who wanted to fly away into the sky […] all of them must learn to know me, in order that my life not be lived for myself alone […].” ’ (p. 497).

Discussion

One reading of this passage would see it as a description of recovery from grief – the gnarled oak tree, with its lopped-off branches representing the isolation and withdrawnness of loss; its burgeoning forth next day, a mark of the renewal and hope and the overcoming of despair. The transformation is triggered by Prince Andrei’s fleeting encounter with Natasha, his feeling the first flickers of love. The oak tree and the rising sap of spring here would be no more than a ‘pathetic fallacy’, in which neutral events in nature are used sentimentally and therefore ‘fallaciously (according to Reference Ruskin and ClarkRuskin (1964 reprint), who coined the phrase in 1856) to illustrate human emotions.

But from the point of view of ‘eco-spirituality’ the passage has a literal as well as metaphorical message. Prince Andrei, partly through his mother-deprived and father-dominated upbringing, partly through bereavement, partly due to his intrinsic character – arrogant, self-centered, cynical – is disconnected and emotionally avoidant, spurning the spring life that teems all around him. Then, through his ‘instinctive curiosity’ (the exploratory vector that in its full form arises out of secure attachment (Reference HolmesHolmes 2014b)), he encounters Natasha. This reaching out is a first step away from his egocentricity. He sees that there is another centre of existence, independent of – and possibly indifferent to – himself.

Narcissistic wound

This very indifference is ‘a blow to his narcissism’ (Reference FreudFreud 1909: p. 340); but because it is contained (within his room, by the beauty of the night, within the compass of the novel and its author) it stimulates him to ‘mentalise’ (Reference HolmesHolmes 2010). He begins to see himself from the outside, and the Other (Natasha) from the inside. He experiences desire – to be connected to the girl, but also to nature, to ‘swoon and sway’, to leave his ‘knotted fingers and scars’ behind. The pattern that connects is not arbitrary but a psychospiritual reality – an ‘arbor-tree’! Man is part of nature, and the ‘green fuse’ (Thomas 1957, in Reference Davies and MaudDavies 2000) that drives the oak tree is the same biological force that (re)-awakens in him hope and love and compassion.

Natasha’s self-hugging can be seen as an adolescent first step towards sexual relatedness, but the libido or life force (with its hormonal and neurological underpinnings) is consonant with the energetic processes captured by the notion of ‘spring’ – sappy green leaves, caroling nightingales, smiling birch trees. There is a pervasive pattern running through Andrei’s metamorphosis to and from the nature to which he opens himself. His is a spiritual as well as a psychological awakening.

The oak tree passage also illustrates an ethical value central to psychotherapy: the movement from isolation to relatedness, from non-mentalising egocentricity to empathy with the other and with oneself. Implicit in the latter is the ‘golden rule’ of reciprocity: do unto others – and to nature – as one would have them do unto oneself. The eco-spiritual case in relation to the oak tree story suggests that the golden rule is not merely a covert form of self-interest – the selfish gene knowing which side its bread is buttered. Implicit is the view that at a fundamental level the Other is oneself: made from the same stuff, with the same desires, hopes, fears, vulnerabilities and ambitions, and that both Self and Other are part of a continuity of nature that stretches beyond the merely human.

Another psychotherapeutically relevant theme is the inescapability of suffering. Prince Andrei is clearly unhappy – albeit in the typically avoidant pattern of deadened feelings. The lyrical tone of the oak tree passage means that full acknowledgment of psychic pain is postponed until later in the novel, when Prince Andrei is mortally injured in bloody battle and nursed through his terminal illness by Natasha. Only then does the extent of his ‘wound’ and suffering unto death become explicit. Nature, Tolstoy implies, including man’s nature, truly is red in tooth and claw. But it is within the compass of the novel – and of psychotherapeutic psychiatry (Reference Bloch, Green and HolmesBloch 2014) – to counterpoise that reality with love, and mark out mentalising pathways by which pain can be tolerated and transcended.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.