Introduction

Child support (child maintenance) refers to the financial obligations of separated parents in which one parent (historically the father) is obligated to pay cash to the other parent (historically the mother) to share the costs of raising their children (Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Bradshaw and Davidson2007). Child support policy is an important aspect of many countries’ family policies, as it can be seen as revealing a country’s perspective on the state’s, fathers’, and mothers’ roles in providing financial support and caring for children post-separation. Moreover, a typical aim is to alleviate single-parent family poverty. But the models scholars have used to categorise a country’s approach to family policy have not generally incorporated child support policy. In this article, we explore whether this can be done.

Two important policy dimensions incorporated into family policy models are the generosity of social security benefits and the extent to which gender equality is prioritised. Both dimensions have implications for the level of child support expected. Countries with more generous benefits may expect less from separated parents because support of children is seen as a state, as well as a private, responsibility. In contrast, countries with less generous benefits may require more child support, based on a philosophy in which parental responsibility is key. Gendered role expectations within a country will also have implications for child support because children typically live with their mother after separation (Zilincikova, Reference Zilincikova2021). Therefore, if fathers are assumed to be the primary breadwinners and mothers the primary carers, a father would probably be required to pay substantial support after separation. In contrast, countries that expect both mothers and fathers to be in the labour force might require less in child support. Beyond these general expectations, predictions about how the levels of child support are related to family policy models in a typical separated family in which children live most overnights with their mother (sole custody) have not been extensively tested, and this is the first goal of this article.

However, we are also interested in how child support fits into policy models in an emerging but less common separated family form, shared care, in which children spend roughly equal amounts of time with each parent. This is the second goal of this article. Shared care arrangements are increasing in many countries; recent estimates of shared care are around 35 per cent of divorcing parents in Belgium, Sweden, and the U.S. state of Wisconsin, (Sodermans et al., Reference Sodermans, Koenraad and Gray2013; Smyth, Reference Smyth2017; Zilincikova, Reference Zilincikova2021). Despite the increase in shared care, it is often true that social policy struggles to keep up with changing family patterns (Meyer and Carlson, Reference Meyer and Carlson2014; Berger and Carlson, Reference Berger and Carlson2020), so we explore whether and how policies respond to this family form.

We first briefly describe a common family policy model that contains three distinct approaches; like other policy models, this schema has not incorporated expectations about the level of child support. We use the general principles in the scheme to generate hypotheses about the level of child support that would be expected in each policy approach for both a typical mother custody case and a shared care case. We then examine data on expected child support orders for these two cases in thirteen countries that represent the three family policy models. In addition to comparing levels of child support expected, we employ a simple one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to see if the variation in support expectation across the three approaches is greater than the variation within an approach, which would suggest that child support fits into these general family policy approaches.

This article builds on a small previous literature and makes several novel contributions. First, whilst some articles have shown the level of child support expected in different countries in a typical separated family (Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Bradshaw and Davidson2007; Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Hakovirta and Davidson2012), this work has been largely exploratory and descriptive. We bring in the framework of a family policy model to generate hypotheses about the expected level of support in countries with different policy schemes, and then test these hypotheses. Second, we extend this family policy model to generate hypotheses about the level expected in an emerging type of separated family, shared care, and then test these hypotheses. Third, Claessens and Mortelmans (Reference Claessens and Mortelmans2018) provided a comparative analysis of the operational rules for child support in shared care cases and tried to link these rules to policy models, but they did not incorporate the child support amounts. We examine the level of support expected in specific family cases to make a more explicit comparison of the amounts owed. Fourth, we cover more countries (13) with updated data than had been available in some of the previous work. These enhancements contribute to the literature on family policy models.

Country contexts, policy models, and the connection between policy models and child support

In this section we first provide background data on the thirteen countries we study. We then turn to family policy, providing an overview of the family policy model we use and data on policies in our countries. Third, we briefly review the limited prior research on child support orders in a typical case in which children live primarily with their mother and an emerging case in which there is shared care. Finally, we extend the family policy model to propose the level of child support expected in both the mother-custody and the shared-care case.

The thirteen countries and the context of policy

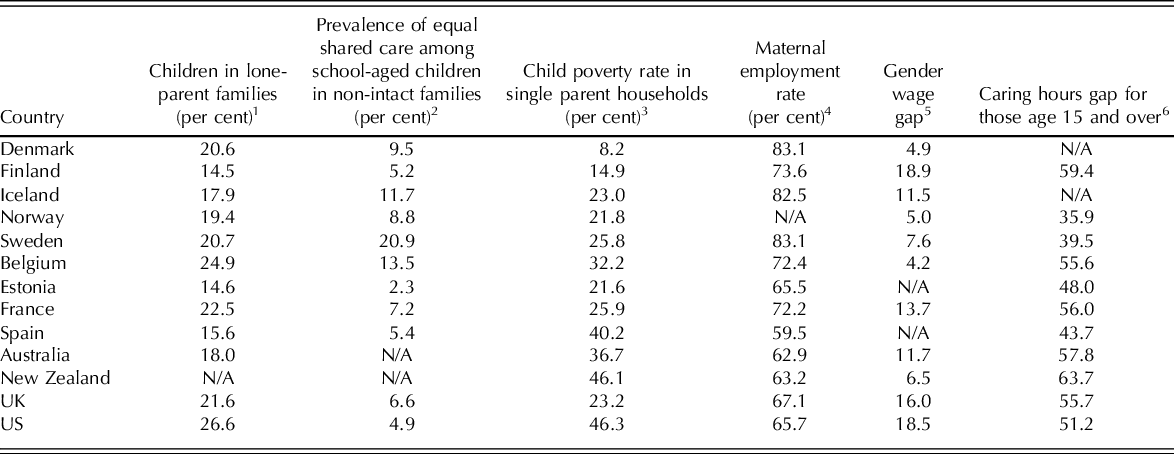

To explore whether child support expectations are related to other features of family policy we study the thirteen countries listed in Table 1. The first three columns provide indicators of the need for child support policy in these countries. The prevalence of children living in lone-parent families ranges from 15 per cent of children (Finland and Estonia) to 25-27 per cent (Belgium and the US). The proportion of children in non-intact families who spend equal time in two houses (shared care) varies substantially across these countries, from below 5 per cent in the US and Estonia to over 20 per cent in Sweden (Steinbach et al., Reference Steinbach, Augustijn and Corkadi2021). The countries also vary substantially in the poverty rates for those in single-parent families, with rates over 35 per cent in Spain, Australia, New Zealand, and the US, and under 10 per cent in Denmark.

Table 1 Context of family policies in 13 countries

Notes:

1. Distribution (percent) of children (aged 0-17) by presence and marital status of parents in the household (OECD, 2019).

2. From 2002, 2006, and 2010 Health Behavior in School-aged Children study, from Steinbach et al. (Reference Steinbach, Augustijn and Corkadi2021)

3. Relative income poverty rate in single adult household with at least one child, percent in 2016. Iceland 2015, NZ 2014. Poverty threshold 50 per cent of median disposable income (OECD, 2019).

4. Employment rates (per cent) for women (15–64 years old) with at least one child aged 0–14, 2014 or latest year available. For Iceland: employment rate of mothers aged 20–49 with one child (Eydal et al., Reference Eydal, Rostgaard, Hiilamo, Eydal and Rostgaard2018).

5. The gender wage gap is the difference in median earnings expressed as a percentage of the median earnings of men. Full-time employees. 2019 or latest available (OECD, 2020).

6. The caring hours gap is the difference in the proportion of hours in care work for women and men expressed as a percentage of the hours in care for women. 1999-2013. Hours in care work from OECD (2019).

Because child support rules can embody expectations about roles of mothers and fathers, the last three columns focus on some gender equality measures. Maternal employment rates differ across the countries, from 60 per cent (Spain) to 83 per cent (Denmark, Iceland, and Sweden). The gender wage gap shows high levels of inequality (large gaps between men’s and women’s wages) in Finland and the US, and relatively low levels in Belgium, Denmark and Norway. Finally, time use surveys show a gap in time spent in caring by men and women. Lower percentages would denote no gap. All countries show large gaps, larger than the gaps in earnings. (This is consistent with other work showing that while labour market gaps have been decreasing, gaps in caring have been more entrenched (e.g. Kan et al., Reference Kan, Sullivan and Gershuny2011). Relatively smaller gaps are seen in Norway and Sweden, with the largest gaps in New Zealand, Finland, and Australia.

Family policies

Family policy is an umbrella of instruments that includes both ‘explicit’ and ‘implicit’ policies related to families with children (Kamerman and Kahn, Reference Kamerman and Kahn1978; Eydal and Rostgaard, Reference Eydal and Rostgaard2018; Nieuwenhuis and Van Lancker, Reference Nieuwenhuis and Van Lancker2020). Family cash and tax benefits, parental leave policies, and support for early childhood education and care (ECEC) are usually identified as important components of family policies. Industrialised countries have been categorised into a number of distinctive family policy models based upon their different strategies for supporting families with children (e.g. Korpi, Reference Korpi2000; Gornick and Meyers, Reference Gornick and Meyers2003; Hantrais, Reference Hantrais2004; Thévenon, Reference Thévenon2011). The family policy models are related to, but distinct from, the substantial literature on welfare regimes (e.g. Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Lewis, Reference Lewis1992). Family policy models vary in their levels and types of support but also in their aims, particularly whether and how they encourage women’s employment, father’s caring role, and gender equality. Some authors have focused on the concept of defamilisation, or the extent to which the state enables women to have enough economic support to live outside of families (e.g. Lister, Reference Lister, Baldwin and Falkingham1994; Cho, Reference Cho2014; Lohmann and Zagel, Reference Lohmann and Zagel2016).

In this article, we draw from the work of Korpi (Reference Korpi2000) and Korpi et al. (Reference Korpi, Ferrarini and Englund2013). Incorporating some ideas related to defamilisation, they build their family policy models based on two dimensions of a country’s support for families. First, the ‘dual-earner support’ dimension can be seen by accessible ECEC that facilitates the employment of both parents. A particular type of parental leave is also consistent with this type of support: to incentivise female employment, prior earnings are a requirement for paid parental leave, and leave levels are linked to prior earnings, rather than being a flat amount. Second, the ‘traditional family’ dimension has as its prototypical policy a cash benefit to families that does not require prior labour force participation. Family tax benefits can be allowances or credits. Benefits can be flat-rate or lump-sums, including: childcare leave benefits paid in low amounts after the termination of earnings-related benefits; child allowances paid in cash or as tax benefits; lump-sum maternity grants; or tax deductions for workers with a dependent spouse. Regardless of the form, the distinguishing feature is a combination of fairly generous cash benefits and weak day care services. Traditional family support then tends to sustain male breadwinner families where women are homemakers.

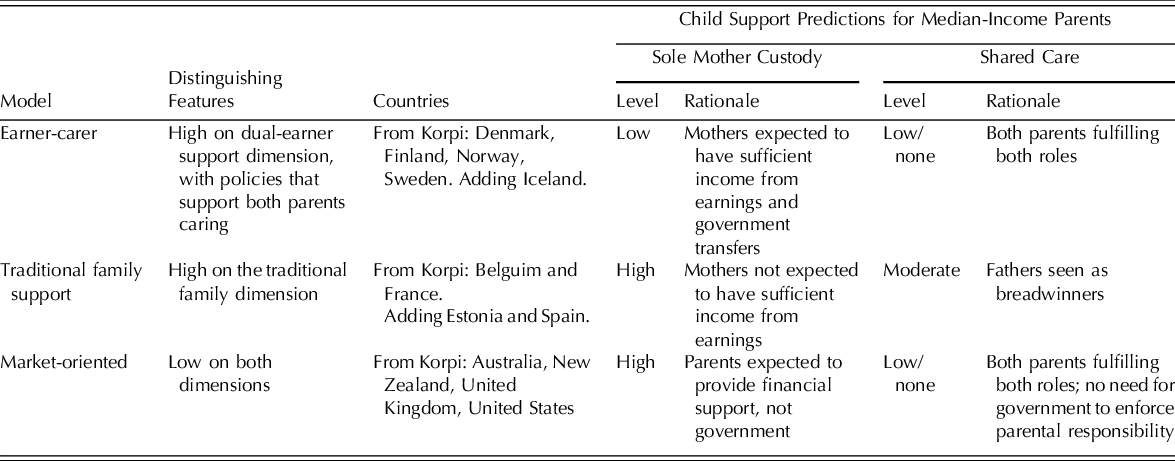

Based on whether countries are high or low on these two dimensions, Korpi (Reference Korpi2000) and Korpi et al. (Reference Korpi, Ferrarini and Englund2013) classified countries into three different family policy models, as shown on Table 2: ‘earner-carer,’ ‘traditional family support,’ and ‘market-oriented.’

Table 2 Three family policy models and child support predictions

Earner-carer models are characterised by relatively low levels of cash and tax benefits for families but high levels of public support for paid parental leave (for both parents) and childcare. Policies aim to support the care of young children and to promote gender equality (Eydal et al., Reference Eydal, Rostgaard, Hiilamo, Eydal and Rostgaard2018). Numerous studies have shown that the earner-carer countries encourage balancing work and care responsibilities and promote women’s full-time employment (e.g. Gornick and Meyers, Reference Gornick and Meyers2003; Ferragina, Reference Ferragina2019). Table 2 lists four of our countries that Korpi (Reference Korpi2000) and Korpi et al. (Reference Korpi, Ferrarini and Englund2013) classified as earner-carer models. Based on its policies (Eydal et al., Reference Eydal, Rostgaard, Hiilamo, Eydal and Rostgaard2018), we add Iceland, which they did not consider. Table 3 shows that these earner-carer countries do spend the highest percentage of their GDP in services to children, and generally have high rates of expenditures on ECEC. Their family leave policies are generally more generous, particularly for fathers (though in these countries, as well as elsewhere, take up of leave for fathers is not universal; see Koslowski et al., Reference Koslowski, Blum, Dobrotić, Kaufman and Moss2020).

Table 3 Family policies in 13 countries

Sources: Korpi, Reference Korpi2000; Korpi et al., Reference Korpi, Ferrarini and Englund2013; OECD, 2019.

Notes:

1. Public spending on services for families with children includes the direct financing or subsidisation of ECEC facilities, public childcare support through earmarked payments to parents, public spending on assistance for young people and residential facilities, and public spending on family services, including centre-based facilities and home help services for families in need. Child-related cash transfers to families with children, includes child allowances (which are sometimes income-tested, and with payment levels that in some countries vary with the age or number of children), public income support payments during periods of parental leave, and, in some countries, income support for single-parent families. (OECD, 2019).

2. Data are adjusted for cross-national differences in the compulsory age of entry into primary education. For example, in some (Nordic) countries children enter primary school at age 7, with almost all attending pre-primary education the year beforehand. In order to improve the comparison, expenditure on these 6-year-olds is excluded (using estimates based on the number of 6-year-olds using pre-primary services. (OECD, 2019).

3. Family leave for mothers refers to paid parental leave and subsequent periods of paid home care leave to care for young children. Paid leave for fathers refers to entitlements to paternity leave, ‘father quotas’ or periods of parental leave that can be used only by the father and cannot be transferred to the mother, and any weeks of sharable leave that must be taken by the father in order for the family to qualify for ‘bonus’ weeks of parental leave. Data reflect entitlements at the national or federal level only, and do not reflect regional variations or additional/alternative entitlements provided. Total paid leave in weeks is calculated as the ‘average payment rate’ (the proportion of previous earnings replaced by the benefit over the length of the paid leave entitlement for a person earning 100% of average national full-time earnings) times the number of weeks of paid leave. In most countries benefits are calculated on the basis of gross earnings. Tables PF2.1A and PF2.1B. (OECD, 2019).

Traditional family support models provide high levels of cash and tax benefits for families with children, but services and ECEC have traditionally been poorly supported, which can be seen as promoting traditional roles. Korpi (Reference Korpi2000) and Korpi et al. (Reference Korpi, Ferrarini and Englund2013) included in this group Belgium and France. We incorporated two countries that they did not classify, Estonia and Spain. We count Estonia as being closer to the traditional family policy model than the earner-carer one (though Bäckman and Ferrarini (Reference Bäckman and Ferrarini2010) consider it a mixed model). Table 3 shows Estonia has relatively high levels of cash transfers and very generous paid leave for mothers and does not compare well to other countries we have designated as earner-carer when it comes to spending on services, ECEC spending, or total paid leave for fathers. Moreover their long paid leave for mothers may inhibit maternal employment (Ainsaar, Reference Ainsaar2019). We classify Spain as a traditional family support model (although it does not have generous cash benefits for families), based on the scarcity of public services for young children, and the limited amount of provisions for reconciling family and employment (Flaquer, Reference Flaquer2000). Table 3 shows that the four countries we classify as traditional family support tend to have higher levels of cash transfers for children, lower expenditures on ECEC, and less generous paid leave than the earner-carer countries.

Market-oriented models differ considerably from the other two models as market solutions are generally preferred over state support. These countries are marked by overall low levels of support for families, minimal parental leave for fathers and a reliance on private family childcare provision (though this may be subsidised). Four of our countries were categorised by Korpi as market-oriented models. While the archetype for this policy model is clear, Table 3 shows that these general statements are not always seen in these indicators. Current cash transfers for children, thought to be low, are actually higher than in all the earner-carer countries (except for the United States). Still, child-related services and ECEC expenditures are less than in the earner-carer countries, and more comparable to the traditional family countries. Moreover, leave policies are the least generous, and leave designated for fathers is especially lower than the other two models.

Child support expectations when children live with mothers and when parents share care

A small literature has provided data on the level of child support expected in different countries, beginning with Corden (Reference Corden1999). Most studies used an approach in which country experts provide the amount of support that would be ordered in a hypothetical family. Research has typically considered a family in which the children live mostly with their mother and this is still the most common post-separation living arrangement (Zilincikova, Reference Zilincikova2021), although shared care has also been explored. Incomes considered have included unemployed parents, lower-income parents, parents with typical (median) incomes, and parents with above-average incomes. A clear finding of this research is that the amount of support expected varies substantially across countries. Skinner et al. (Reference Skinner, Hakovirta and Davidson2012) showed the amount expected in the US is more than twice the amount expected in the UK, Iceland, or Finland with typical income. Another recent study (Hakovirta and Skinner, Reference Hakovirta, Skinner, Bernardi and Mortelmans2021) also shows particularly high amounts in the US, with Estonia and Spain also expecting substantially more than Scandinavian countries.

Whilst predictions about characteristics of countries associated with the level of support were not made nor tested, some of the studies have used a typology to explore differences across countries. The most common differentiation is based on the type of institution responsible for decisions about child support obligations: some countries use courts, others administrative agencies, and others a mixture of both (Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Bradshaw and Davidson2007). However, recent studies have shown that grouping countries according to institutional arrangements does not fully explain the differences in child support policies or outcomes (Meyer and Skinner, Reference Meyer and Skinner2016; Hakovirta and Skinner, Reference Hakovirta, Skinner, Bernardi and Mortelmans2021).

Three prior studies have examined the level of child support obligations in shared care cases across several countries. Skinner et al. (Reference Skinner, Bradshaw and Davidson2007) reported the level of child support orders for fourteen countries showing which countries set high, low and no child support orders for parents with shared care. Recent research (Hakovirta and Skinner, Reference Hakovirta, Skinner, Bernardi and Mortelmans2021) compared the order amounts expected for a sole custody case to that of a shared care case that was otherwise identical, considering up to thirteen countries. They found no consensus across countries on what the child support obligations should be in more equal shared care cases. Commonly however, countries took some partial account of shared care, adjusting the obligation downwards.

As an alternative typology, Claessens and Mortelmans (Reference Claessens and Mortelmans2018) have recently divided countries into universal caregiver, universal breadwinner and male breadwinner models and examined child support in shared care families. Their analysis was focused on the process of setting orders, rather than the amount; they found that the models did not consistently predict child support processes in shared care cases and that a country’s policies concerning gender equality did not consistently affect these processes in the shared care case.

Given this previous literature, we build on these ideas but use Korpi and colleagues’ approach to family policy. We make predictions for the level of support expected in each of their three family models, differentiating between the amount expected in a typical case in which children live with their mothers and an emerging case in which children spend equal time with both parents.

Family policy models and child support expectations

What does the policy logic embedded in the three family policy models suggest about the level of child support orders? Table 2 provides a summary of our expectations in the sole-custody case. Substantial child support for single parents is not needed in the earner-carer countries because both parents are expected to be earners. Moreover, governmental family benefits provide single parents with relatively generous resources, making support from the other parent less necessary. In traditional family support countries, mothers’ employment rates are relatively low (Nieuwenhuis and Maldonado, Reference Nieuwenhuis and Maldonado2018). To relieve poverty, child support payments are needed, so we expect high orders. The market-oriented countries generally have low levels of public support for children; as a result private child support may be particularly important post-separation. Thus, our first hypothesis is: ‘if the mother is the primary carer and has sole custody, countries with an earner-carer model will have lower child support expectations than countries with either a traditional family policy model or a market-oriented model’.

The expectations for child support may differ in a separated family in which both parents have equal caring responsibilities (last columns of Table 2). In earner-carer countries, equal caring responsibilities between parents combined with equal earning responsibilities mean there need not be financial transfers. In traditional family countries, we anticipate that even in the shared care case, a father will be expected to provide some child support because he is still seen as a breadwinner. In market-oriented countries, the shared-care case expectations may vary by income: it may be high in low-income cases given the lack of other supports for families, and it may be low for moderate-income cases given the general preference for non-governmental intervention when perceived not to be ‘needed.’ In the hypothetical cases we test, both parents have median incomes (for their sex). Consequently, we anticipate low orders since there will be less need for government intervention when families have typical incomes. Thus, our second hypothesis is: ‘if both parents have median incomes and share care equally, countries with a traditional family model will have higher orders than in either the earner-carer or the market-oriented countries’.

Finally, the logic of policy models is that the countries within a particular type are more similar to each other than those who follow a different model type. As a result, we suggest that the variation of orders within any family policy model should be lower than the variation between models.

Data and methods

We use an expert informant method, in which individuals with extensive knowledge of their own country’s child support systems were recruited to complete a detailed standardised questionnaire about child support policy at the end of 2017. However, child support systems in Spain and the U.S. are not uniform nationally. So, in Spain the policy relates to Catalonia and in the U.S. to five states (California, Illinois, Minnesota, South Carolina, and Wisconsin). The five U.S. states provide varied approaches and different models to determine orders (U.S. NCSL, 2020), different approaches to shared care (Brown and Brito, Reference Brown and Brito2007), and include states with cost-effectiveness ratios above and below the national average (U.S. DHHS, 2019). We average levels of support expected in these five states to represent the United States.

The questionnaire considered processes for determining, monitoring, enforcing, and revising child support, with a particular focus on shared care and new families. In addition to providing general information on child support policies, the informants were presented with scenarios (described below) and asked to calculate the amount of child support a parent would be required to pay according to their country’s policies and legal guidelines (see details Hakovirta and Haapanen, Reference Hakovirta and Haapanen2020). This method was used successfully in prior child support research (e.g. Corden, Reference Corden1999; Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Bradshaw and Davidson2007; Reference Skinner, Hakovirta and Davidson2012; Reference Skinner, Meyer, Cook and Fletcher2017; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Skinner and Davidson2011; Hakovirta and Eydal, Reference Hakovirta and Eydal2020) and facilitates comparison because the policies in different countries are applied to the same particular scenario.

The first scenario provided a sole custody case, in which there were two children and each parent was working full time and had sex-specific median earnings for their country. (Using median earnings allows us to focus on a fairly typical case; using median earnings by sex allows us to reproduce the gender pay gap within the country.) The father has regular visitation (two overnights every other week). Informants reported whether there would be a formal child support arrangement and if so, the monthly amount that would be ordered. In the second scenario the situation was otherwise exactly the same as in the sole custody case, but the children spend equal time with each parent. We asked the informants to explain if (and how) the child support outcomes would differ.

Within each country we first show the amount of child support expected in the sole custody case. We show amounts in U.S. dollar PPP per child, facilitating a meaningful cross-country comparison. We then contrast this amount with the amount expected in the (otherwise identical) shared care case. In both cases we consider whether our hypotheses about the level expected holds. Because of our interest in whether family policy models are good explanations for differentiations in child support policy, we also conduct a straightforward, one-way ANOVA on each country’s amount of expected child support. We compare the variation in amounts within the three family policy models (that is, within the five countries in the earner-carer model, within the four countries in the traditional model, and within the four countries in the market-oriented model) to the variation between models.

These analyses are therefore descriptive and the data are based on hypothetical family scenarios and are not based on actual cases using representative samples. Note we are interested in the amount expected (the order), regardless of whether it is actually paid.

Results

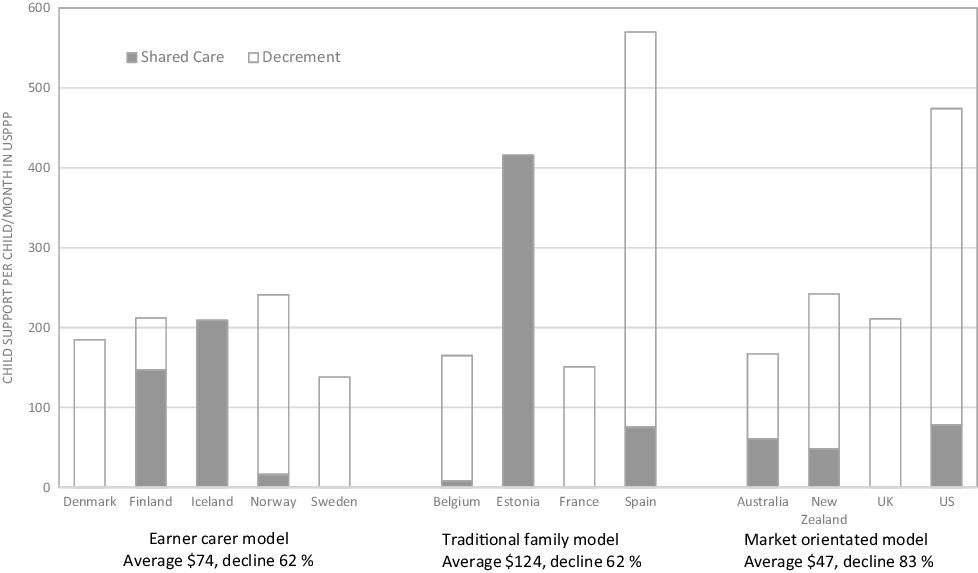

Figure 1 presents the amounts expected in the sole custody scenario. In sole custody, the father is expected to pay child support in all countries, but the amounts are dramatically different. Orders are clearly lowest in Sweden, followed by France, Belgium, Australia, and Denmark (less than $200/child PPP per month). In the next set of countries—Finland, Iceland, Norway, New Zealand, and United Kingdom—amounts are between $200 and $250 per month per child. The expectations are highest in Spain, followed by Estonia and in the U.S. (above $400 PPP per month per child). We expected that countries with an earner-carer model would have lower orders than countries with a traditional family policy model or a market-oriented model. This hypothesis is supported. The five countries with the earner-carer model have the lowest average order, $197, compared to $326 for the traditional family policy model and $274 for the market-oriented model. However, within the traditional family policy model and the market-oriented model there is substantial variation between countries; in contrast, the earner-carer countries have similar expectations.

Figure 1. Child support amounts in the sole custody scenario, in 2017

In Figure 2, the height of each bar repeats the amount expected in the sole custody case from Figure 1. We have shaded in the portion of the bar that corresponds to the amount expected if these parents shared care equally. The amount of child support expected is much lower in most of the countries examined. In fact, in Denmark, Sweden, France, and the United Kingdom, child support is annulled in this shared care scenario. In Norway, Belgium, Spain, Australia, New Zealand, and the U.S. states, there is still an order, but the orders are low (below PPP$100 per month). In contrast, in Finland, the obligation falls but is still more than half of the sole custody level, and in Estonia and Iceland, the obligation does not change from the sole custody case.

Figure 2. Child support amounts in the shared care scenario compared to the sole custody scenario, in 2017

We anticipated that the earner-carer countries would not set child support orders, or they would be very low. Orders are substantially less than they were in the sole custody situation, averaging $74. Denmark, Norway, and Sweden follow the prediction, as their orders are set to zero or to a very low amount. However, the two other earner-carer countries do not follow predictions. Iceland has no adaptation for the shared care situation and in Finland there is only a small reduction.

In the countries with a traditional family policy model, we expected that child support levels would remain relatively high in the shared care case. The average amounts expected are indeed higher than the other two family policy models, averaging $125, and they have relatively small reductions in child support for shared care (62 per cent decline), supporting our hypothesis. However, looking more closely, there are substantial differences within the countries in this traditional family policy grouping. Estonia is consistent with our hypotheses, having high expectations in both the sole custody and shared care cases. Spain (Catalonia) is consistent for the sole custody case, having a relatively high order, but, contrary to our expectation, the order falls substantially in the shared care case. Belgium and France do not fit our hypothesis well for either case.

For the market-oriented family policy model we hypothesised that orders would be low in this shared-care case. As anticipated, average orders are low (in fact, the lowest), averaging $47, and the average percentage decrease in orders when moving from the sole custody case to the shared care case is 83 per cent. This is the largest decline of the three family policy models. Moreover, in contrast to the other two models in which some countries did not follow expectations, all countries take a relatively similar approach to shared care of a large decline in the order or even annulling it altogether.

We were also interested in whether the variation of child support expectations within models would be lower than the variation between models. A one-way ANOVA was conducted. Considering the sole custody case, there is no statistically significant difference across family policy models (F (2, 10) = 1.01, p = .3981). Similarly, there was no statistically significant difference in the shared care case across family policy models (F (2,10) = 0.40, p = .6817). In other words, although the predictions about expectations of the level across models generally held, the models have more variation within them than there is across models.

Discussion

This article focuses on child support expectations in a sole custody case and in a case in which separated parents share care of their children equally, examining whether child support requirements are consistent with family policy models. We focused on separated families because the distribution and relative economic value of both market work and care becomes monetised by child support policy.

We had two hypotheses. The data clearly support our hypotheses for the sole custody case: countries with an earner-carer family policy model have lower child support orders than countries with a traditional family model or a market-oriented model. Our hypotheses about shared care were also generally supported. Earner-carer countries and market-oriented countries do have substantially lower orders in shared care than in sole custody cases, and these orders are lower on average than in countries with traditional family models. However, orders also decline substantially in the traditional family countries (albeit by not as much as in the countries representing the other policy models).

While the general predictions for the family policy models hold overall, there is more variation between countries within family policy model types than there is across types: the family policy typology does not adequately predict child support orders. This illustrates well what Nygren and colleagues (Reference Nygren, White and Ellingsen2018: 672) call a ‘paradox’ where ‘there may, at least in some areas, be a greater variation within a welfare cluster than between.’ We first discuss the countries that do not fit well, and then, based on these exceptions, summarise possible explanations for why child support does not fit into family policy models.

All earner-carer countries are consistent in the sole-custody case; however, when parents share care, Finland and Iceland do not substantially reduce orders, which would be expected. This could be from lags in adapting policies in light of new family forms. Alternatively, among the earner-carer countries, Finland and Iceland have the largest gender wage gaps and Finland also has the lowest maternal employment rate and highest gender care gap (see Table 1). Child support is not altered much in shared care cases because of apparent continuance of gender differences in earning and caring practices, and child support policy prioritises fathers’ breadwinning role (Hakovirta et al., Reference Hakovirta, Cook and Sinclair2020)

In the traditional family policy countries, only Estonia follows the prediction of relatively high orders that are not reduced substantially for shared care. (The lack of adjustment to the order in Estonia could also be related to the relatively limited number of shared-care cases seen in Table 1). Spain has the expected high order in the sole-custody case, but (contrary to expectation) this is dramatically reduced in shared care. Spain does have the lowest rate of maternal employment among these countries (Table 1), so its family policy in the typical case may reflect that mothers are seen as the primary carer. In this context mothers who are willing to share care post-separation may be seen as choosing to take on more of a breadwinning role, and thus perhaps the father does not need to be required to provide financial support. Both Belgium and France have orders that are more like the earner-carer model (relatively low orders in the sole-custody case that decline substantially in the shared-care case). Interestingly, Belgium has the lowest gender wage gap of all thirteen countries and both Belgium and France have relatively high maternal employment rates among the traditional family types, so it might be regarded that child support is needed less in shared care cases.

In the market-oriented countries, only the U.S. (in the five states) fits the ideal type, with high orders in the sole-custody case that are substantially reduced. The other countries do reduce orders (or annul them) in the shared care case, as expected, but their orders in the sole-custody case are also lower than anticipated. There is nothing obvious in the contextual indictors in Table 1 that might explain this. One reason may be stakeholder advocacy: child support orders in Australia and the UK may not only have been shaped by family policy influences, but also by strong fathers’ rights movements. These movements have successfully called for greater recognition of shared care and reductions in child support orders for all types of cases (Cook and Skinner, Reference Cook and Skinner2019).

An in-depth analysis of why various countries do not fit predictions is beyond the scope of this article. But several factors were identified that highlight the general challenges to family policy typologies. Difficulties with creating policy typologies that can be seen here include potential inconsistencies in policy logics across policy areas and countries whose policies do not fit ideal types either because they fit in between typologies or because of different rates of policy change such that models created at one point in time may not fit the current context for some countries. Additionally, stakeholder advocacy which can lead to inconsistent policy packages and overturn path dependence; and the need for a limited number of types for the classification to be analytically useful (which is in direct conflict with taking into account each country’s unique context and history). Our analysis also has some limitations. We have a limited number of countries, and here we examine only one family income level (albeit a typical income). Thus, it is unclear whether our conclusions would hold with more countries or with more families within a country. Adding more data points within or across countries could enable one to add more complexity to the analysis, controlling for some country differences that could be correlated with policy differences. Another limitation, which is typical of this type of comparative research, is that the data are from only one policy expert in each country; including multiple experts within a country could lead to more robustness. Even with these limitations, the analysis shows that predictions developed from a well-known family policy typology do hold for the level of child support expected in a case in which children live primarily with their mother and an emerging case in which the parents share time equally. However, there is a substantial amount of diversity within the models, which may limit their usefulness. This diversity is consistent with a different documentary analysis of child support policy procedures, which found no evidence that similar family policy models would treat separated parents who were sharing care in similar ways (Claessens and Mortelmans, Reference Claessens and Mortelmans2018). Beyond these general difficulties and limitations, fitting child support into family policy presents several unusual challenges that have a specific bearing on this analysis and the future direction of research. First, many family policy models are built around the gender roles expected when parents live together; child support policy will not fit these models well if different gender expectations emerge when parents separate. For example, countries that expect fathers will be the primary earner and the mother the primary carer in intact families may expect mothers to take on more earning alongside caring post-separation, which could lead to different types of policies pre- and post-separation (Hakovirta et al., Reference Hakovirta, Cook and Sinclair2020). Moreover, parents choosing an emerging family form (in this case, shared care), may further challenge typical gender assumptions. For example, fathers and mothers who share care in a country that typically expects mothers to be the primary carers may face a policy inconsistent with the basic approach in the country. More broadly, a country’s policies may change to accommodate an emerging family form only when the number of cases reaches a certain level. As separating parents move away from typical living arrangements and toward new equal care forms, child support policy may be slow to respond, and when it does respond, may respond in ways that are particular to this family form, rather than to a country’s general approach to policy (this may be particularly so if pressure is successfully applied by powerful advocacy groups).

Second, the different institutional arrangements found in child support policies (court vs. agency) may complicate attempts to categorise a country’s family policy. In court-based countries, courts can ratify private child support agreements made between parents or decide amounts where parents cannot agree (Hakovirta and Skinner, Reference Hakovirta, Skinner, Bernardi and Mortelmans2021). As a result, court-based child support outcomes may not be consistent with other aspects of family policy.

Third, child support policy has multiple and often competing objectives. For example, the goals of child support could include addressing poverty, ensuring parental responsibility, limiting public cost, ensuring children’s right not to be economically disadvantaged by their parents’ separation, or other factors. In part, child support policy can be seen as providing a resource for custodial parents, but it does this in the context of regulating private behaviour, and the tension between resource-focused approaches and regulation-focused approaches may create conflicts (Daly, Reference Daly, Nieuwenhuis and Van Lancker2020). How competing objectives are reconciled can mean that the child support policy that results does not fit into the logics that shape other areas of family policy. In this way, child support is similar to childcare in that competing objectives can lead to different policy features that may or may not be consistent with other family policies (Ciccia and Bleijenbergh, Reference Ciccia and Bleijenbergh2014).

Finally, child support policy has ambiguities that might render it a poor fit with general family policy models. For example, the concept of defamilisation frequently used in general family policy models can be seen as highlighting whether policies enable women to live economically independently from a family. How should child support be considered in this characterisation, as a policy that promotes independence because a mother can afford to live without a partner, or one that promotes dependence because her ex-partner still provides her income through child support payments? Moreover, how do policies that promote shared care fit? As defamilising because a mother can be independent from her children half the time? Or as familising because she is inextricably tied to her ex-partner through co-parenting arrangements? A discussion of these questions is beyond the scope of this analysis, but points to a need for further conceptual work on whether family policy models are good enough for understanding country differences in child support policies and newly emerging separated family forms.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Academy of Finland, grant number 294648.