Introduction

Many older adults want to age in their home of choice for as long possible (Bigonnesse & Chaudhury, Reference Bigonnesse and Chaudhury2019; Wiles, Leibing, Guberman, Reeve, & Allen, Reference Wiles, Leibing, Guberman, Reeve and Allen2012). In response, many countries (including Canada) have developed policies and programs to deliver home health care and community support services as alternatives to institutionalization. Whereas home health care refers to nursing and rehabilitative services typically delivered directly in the home by health professionals (Mah, Stevens, Keefe, Rockwood, & Andrew, Reference Mah, Stevens, Keefe, Rockwood and Andrew2021), community support services refer to programs that are “delivered in the home or community to assist people in coping with health or social problems to maintain the highest possible social functioning and quality of life” (Denton et al., Reference Denton, Ploeg, Tindale, Hutchison, Brazil and Akhtar-Danesh2008, p. 360). Examples of community support services include adult day programs, food delivery (e.g., meals on wheels, congregate dining), homemaking and home maintenance services, transportation, caregiver support, friendly visiting, mental health supports, and case management (Siegler, Lama, Knight, Laureano, & Reid, Reference Siegler, Lama, Knight, Laureano and Reid2015).

Access to community support services is critical for supporting aging in place (Bigonnesse & Chaudhury, Reference Bigonnesse and Chaudhury2019). These services provide support for instrumental activities of daily living (Kuluski, Williams, Berta, & Laporte, Reference Kuluski, Williams, Berta and Laporte2012); promote mental health, social functioning, and quality of life (Denton et al., Reference Denton, Ploeg, Tindale, Hutchison, Brazil and Akhtar-Danesh2008; Ploeg et al., Reference Ploeg, Denton, Tindale, Hutchison, Brazil and Akhtar-Danesh2009); and play a key role in preventing or delaying premature institutionalization (Kuluski et al., Reference Kuluski, Williams, Berta and Laporte2012). Despite these documented benefits, access to community support services may be challenging because of a lack of awareness of them, as well as because of difficulties navigating a complex system that has multiple agencies providing these services.

Community Support Service Use Among Older Adults

Although most community-dwelling older adults reported that they would seek help from a community support service agency if needed (Denton et al., Reference Denton, Ploeg, Tindale, Hutchison, Brazil and Akhtar-Danesh2008; Tindale et al., Reference Tindale, Denton, Ploeg, Lillie, Hutchison and Brazil2011), there are generally low utilization rates of their services. For example, Lehning, Kim, and Dunkle (Reference Lehning, Kim and Dunkle2013) reported in their sample of 1,099 black older adults that only 14.9 per cent accessed functional support services (such as home-delivered meals and homemaking services), 18.9 per cent used home repair and home maintenance services, and 46.6 per cent accessed out-of-home services such as senior centres, congregate dining, and transportation. McKenzie, Lucke, Hockey, Dobson, and Tooth (Reference McKenzie, Lucke, Hockey, Dobson and Tooth2014) reported similarly low utilization rates among older women, but found that rates increased over a 6-year follow-up period from 16.1 to 33.3 per cent for homemaking services, and from 28.7 to 32.1 per cent for home maintenance services.

There may be low utilization rates because older adults often rely on informal networks of friends and family to provide support for transportation and household work, such as cleaning, meal preparation, and home maintenance (Ploeg et al., Reference Ploeg, Denton, Hutchison, McAiney, Moore and Brazil2017; Sinha & Bleakney, Reference Sinha and Bleakney2014). Informal caregivers of older adults however, tend not to access community support services (Hong, Reference Hong2009; Strain & Blandford, Reference Strain and Blandford2002). For example, Hong (Reference Hong2009) reported that informal caregivers of older adults only accessed an average of 1.7 out of 10 services and showed low utilization rates for services offering both direct (e.g., respite services, homemaking services) and indirect (e.g., adult day services, transportation, meal delivery) help. Similar findings were observed in the Manitoba Study of Health and Aging, in which two-thirds of older adult–caregiver dyads had not accessed homemaking services (Strain & Blandford, Reference Strain and Blandford2002). In fact, fewer than 10 per cent were participating in meal delivery programs, adult day centres, and respite care programs, most commonly because the caregiver did not feel that these services were needed, or felt that friends and family were providing adequate support. Other reasons commonly cited for delaying or refusing community support services include pride, reluctance to have someone else in the home, and lack of transportation support to services outside of the home (Ploeg, Matthew-Maich, et al., Reference Ploeg, Matthew-Maich, Fraser, Dufour, McAiney and Kaasalainen2017).

Awareness of Community Support Services Among Older Adults

Lack of awareness also appears to be a key factor contributing to the overall low utilization rates of community support services. Many older adults and their caregivers are unaware of the types of services that are available to help them (Ploeg, Matthew-Maich, et al., Reference Ploeg, Matthew-Maich, Fraser, Dufour, McAiney and Kaasalainen2017), and awareness appears to vary based on service type. For example, in one study of nearly 5,000 older adults living in the community, participants were asked if they thought a specific service (e.g., homemaking) would be available if they needed it (Calsyn & Winter, Reference Calsyn and Winter1999). Findings showed that awareness ranged from 31 to 78 per cent, and was highest for meal programs, transportation, health screening, and senior centres but lowest for reassurance services, adult day programs, respite care, and home repair services (Calsyn & Winter, Reference Calsyn and Winter1999).

Another study conducted in Ontario used a vignette methodology to ask 1,152 older adults via randomized telephone surveys to name a specific community agency that could provide support for 12 different hypothetical scenarios that closely approximated real-life situations commonly experienced by older adults and their families (e.g., caregiver burden and respite, transportation, maintaining independence, financial insecurity). The vignettes were developed by community support service providers and had high face and content validity (Tindale et al., Reference Tindale, Denton, Ploeg, Lillie, Hutchison and Brazil2011). These authors found that awareness of support services may actually be much lower than previous estimates; 43 per cent of those surveyed were unable to identify any specific community agency that could provide support (Tindale et al., Reference Tindale, Denton, Ploeg, Lillie, Hutchison and Brazil2011), and awareness of agencies varied widely, from 1 to 42 per cent, depending on the scenario (Denton et al., Reference Denton, Ploeg, Tindale, Hutchison, Brazil and Akhtar-Danesh2008; Tindale et al., Reference Tindale, Denton, Ploeg, Lillie, Hutchison and Brazil2011). In this study, awareness was highest for transportation services and supports for caregivers (e.g., respite services), but lowest for services helping with chronic disease and ensuring safety, as well as those helping to prevent financial abuse and alcohol misuse (Denton et al., Reference Denton, Ploeg, Tindale, Hutchison, Brazil and Akhtar-Danesh2008; Tindale et al., Reference Tindale, Denton, Ploeg, Lillie, Hutchison and Brazil2011). When specifically asked about scenarios related to maintaining independence (either supporting an aging parent with deteriorating health, or maintaining their own health in the face of declining capacity), fewer than 20 per cent of participants identified a community support service agency as a source of support (Denton et al., Reference Denton, Ploeg, Tindale, Hutchison, Brazil and Akhtar-Danesh2010). Instead, participants noted that they would rely on informal supports or access services through home health care organizations that usually specialize in personal support and nursing care (Denton et al., Reference Denton, Ploeg, Tindale, Hutchison, Brazil and Akhtar-Danesh2010).

Several factors have been found to impact awareness of community support services. For example, some studies report that being older and having lower income and less social support were associated with lower levels of awareness (Calsyn & Roades, Reference Calsyn and Roades1993; Tindale et al., Reference Tindale, Denton, Ploeg, Lillie, Hutchison and Brazil2011). Being knowledgeable about where to look for information on community support services also impacts awareness (Tindale et al., Reference Tindale, Denton, Ploeg, Lillie, Hutchison and Brazil2011), but 14 per cent of older adults did not know how to access this information (Denton et al., Reference Denton, Ploeg, Tindale, Hutchison, Brazil and Akhtar-Danesh2008). Although up to 30 per cent relied on information and referral services such as libraries, newspapers, and other media, approximately one quarter relied on their primary care physician to provide information and make referrals (Denton et al., Reference Denton, Ploeg, Tindale, Hutchison, Brazil and Akhtar-Danesh2008). However, primary care providers lack reliable and up-to-date information on community support services (Ploeg et al., Reference Ploeg, Denton, Hutchison, McAiney, Moore and Brazil2016), and do not frequently make referrals to these services without support of other team members (e.g., case managers) with more expertise in the area (Boll et al., Reference Boll, Ensey, Bennett, O’Leary, Wise-Swanson and Verrall2021; Ploeg et al., Reference Ploeg, Denton, Hutchison, McAiney, Moore and Brazil2017).

Community Support Services in Social Housing

Across Canada, a growing number of low-income older adults are aging in place in social housing (Ontario Non-Profit Housing Association, 2016), which is a subset of affordable housing where rents are geared to income or supplemented with housing subsidies (Housing Services Corporation, 2014). Demand for social housing among older adults continues to outpace supply: in Toronto alone, which is the location of the current study, there were nearly 30,000 older adults on the waitlist in 2020 (City of Toronto, 2021b).

Older adults waiting for social housing experience poor health outcomes (Carder, Kohon, Limburg, & Becker, Reference Carder, Kohon, Limburg and Becker2018) and lack adequate social support (Carder, Luhr, & Kohon, Reference Carder, Luhr and Kohon2016). As a result, vacancies are frequently filled by older adults who identify as vulnerable and require additional supports (Ontario Non-Profit Housing Association, 2015). In fact, older adults in social housing face multiple chronic physical and mental health conditions (e.g., Agarwal et al., Reference Agarwal, Angeles, Pirrie, McLeod, Marzanek, Parascandalo and Thabane2019; Gonyea, Curley, Melekis, Levine, & Lee, Reference Gonyea, Curley, Melekis, Levine and Lee2018; Robison et al., Reference Robison, Schensul, Coman, Diefenbach, Radda and Gaztambide2009). They also report high rates of disability, including low mobility and physical activity levels (Agarwal et al., Reference Agarwal, Angeles, Pirrie, McLeod, Marzanek, Parascandalo and Thabane2019), which lead to difficulties completing instrumental activities of daily living (Gibler, Reference Gibler2003; Robbins et al., Reference Robbins, Rye, German, Tlasek-Wolfson, Penrod and Rabins2000). Unlike other community-dwelling older adults, those living in social housing have limited support from informal networks of friends and family (Sanders, Stone, Meador, & Parker, Reference Sanders, Stone, Meador and Parker2010), which further emphasizes the importance formal community support services to support older tenants aging in place.

Most social housing providers partner with community agencies to offer support services on site. However, like other community-dwelling older adults, access to these services appears to be low. For example, Cotrell and Carder (Reference Cotrell and Carder2010) interviewed 130 older adults in social housing and found that only 21.7 per cent had accessed homemaking services, 14 per cent had support with meal preparation, 11.6 per cent had accessed supports for shopping, and 10.9 per cent had used mental health services. Similar utilization rates were reported by Parton et al. (Reference Parton, Greene, Flatley, Viswanathan, Wilensky and Berman2012) who surveyed 400 older adults in social housing and found that although 55 per cent of tenants were connected to at least one community support service, access to individual services was low: 25 per cent participated in a congregate dining program, 22 per cent used transportation services, and 20 per cent accessed homemaking. Many older adults in social housing also do not have access to a physician or regular medical provider (e.g., Parton et al., Reference Parton, Greene, Flatley, Viswanathan, Wilensky and Berman2012; Smith Black, Rabins, German, McGuire, & Roca, Reference Smith Black, Rabins, German, McGuire and Roca1997), who are known to help older adults access information and referrals to community support services (Denton et al., Reference Denton, Ploeg, Tindale, Hutchison, Brazil and Akhtar-Danesh2008; Ploeg, Matthew-Maich, et al., Reference Ploeg, Matthew-Maich, Fraser, Dufour, McAiney and Kaasalainen2017). Instead, housing staff, such as resident services coordinators, play a critical role in helping older tenants access services by identifying those who need additional supports and making linkages to community services (Canadian Urban Institute, 2020; Sheehan & Guzzardo, Reference Sheehan and Guzzardo2008; Sheppard, Hemphill, Austen, & Hitzig, Reference Sheppard, Hemphill, Austen and Hitzig2022).

Accessing Community Support Services in Ontario

At the time of the present study, community support services in Ontario could be accessed through 14 provincially funded Local Health Integration Networks (LHINs), which no longer exist. The LHINs were region-based non-profit corporations that worked with local health providers and community members to determine health service priorities for their region (see Cheng, Reference Cheng2018 for a review). Although the LHINs did not directly provide services, they planned, integrated, and funded local health services, including home health care and community support services. Referrals to LHIN-funded community support services were facilitated by an LHIN care coordinator, who assessed eligibility and care needs, and made appropriate linkages to service provider organizations. Some services were entirely government-funded, while others had client fees that were on a sliding scale geared to income (Kuluski et al., Reference Kuluski, Williams, Berta and Laporte2012).

The Ontario Community Support Association (2020) reported that in 2017–2018, more than 1,000,000 people across the province, including older adults, caregivers, and people with disabilities, received community support services. During the same period, there were more than 1,900,000 rides provided by transportation services, and 3,100,000 meals delivered by meals on wheels; approximately 50,000 clients served in adult day programs; and nearly 26,000 people were provided with assisted living services (Ontario Community Support Association, 2020).

The Present Study

The present study examined the delivery of LHIN-funded community support services to the ‘seniors’ designated’ buildings at Toronto Community Housing Corporation (TCHC), Canada’s largest social housing landlord. Nearly 15,000 older adults live in the 83 seniors’ designated buildings, where the leaseholder must be 59 years of age or older. Older adults living in TCHC are among the most vulnerable in the city, and many experience poor physical and mental health outcomes that intersect with other vulnerabilities such as racialized and gender-based poverty, systematic racism, language barriers, and unequal access to resources and services (City of Toronto, 2019).

The City of Toronto conducted a review of the TCHC seniors’ designated buildings and identified an inadequate and inconsistent delivery of housing services to senior tenants, and a lack of integration between housing and health services (City of Toronto, 2018). In response, Toronto City Council approved a series of recommendations calling for improved living conditions and services for seniors living in TCHC, with a focus on advancing the strategic integration of housing and health services to help tenants age in place by promoting stable tenancies and improving quality of life.

Among the recommendations approved by Toronto City Council was a new housing services model for the seniors’ designated buildings, which was developed through a tri-partnership with the City of Toronto, TCHC, and the Toronto Central (TC) LHIN. A core objective for this new model was to increase access to health and community support services to ensure that tenants have the supports they need to remain safely in their apartments for as long as possible (City of Toronto, 2019). To achieve this, a new tenant support role was created to help identify tenants who may need additional supports, and TC LHIN-funded care coordinators were designated to each of the 83 buildings to help link tenants to appropriate community support services agencies (see Sheppard, Hemphill et al., Reference Sheppard, Hemphill, Austen and Hitzig2022 for a review of this new staff model). Prior to implementing this new model, we conducted a descriptive analysis of baseline community support service utilization data provided by the TC LHIN to describe (1) what community support services are currently provided to seniors living in the TCHC in the seniors’ designated buildings, and by which organizations; and (2) how access to community support services varies across seniors’ buildings and neighbourhoods.

Methods

This study used data from the TC LHIN Community Business Intelligence database that includes data from community health service providers on mental health, community addiction, and community support services (Amartey et al., Reference Amartey, Liadsky, Solomon, Carter, Holder and Yang2018). The Community Business Intelligence database collects and aggregates individual-level service utilization data across services and providers for all agencies that are located within and funded by the TC LHIN. Study approval was obtained by the research ethics board at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

Data were provided from the 2018–2019 fiscal year (April 1, 2018–March 31, 2019) for all 83 TCHC senior-designated social housing buildings, which were represented by 74 unique postal codes (referred to as “developments”). For each development, data included: (1) the name of the organization providing service, (2) the types of services provided (e.g., meals on wheels, transportation, mental health supports), (3) the number of tenants receiving each type of service, and (4) the total number of unique tenants receiving any TC-LHIN funded community support service. Services with fewer than five clients were supressed to protect privacy. For the present analyses, supressed values were replaced with a value of one to avoid over-estimating service utilization in the buildings.

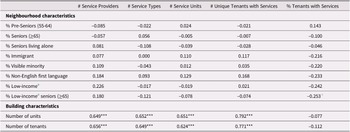

We then conducted bivariate correlational analyses to examine the relationship between neighbourhood characteristics and the provision of LHIN-funded community support services to the TCHC seniors’ designated buildings. Neighbourhood characteristics that were examined included the proportion of people living in private households who were pre-seniors (55–64 years of age), older adults (≥ 65 years of age), low-income, immigrants, visible minorities, and those who did not speak English as a first language. We also examined the proportion of older adults who were low income and the proportion that lived alone. Characteristics for each neighbourhood were extracted from the 2016 Neighbourhood Profiles, which were based on data collected as part of the 2016 Population Census. The neighborhood profiles are available on the City of Toronto’s Open Data Portal (City of Toronto, 2021a). Correlations were conducted using SPSS version 26.

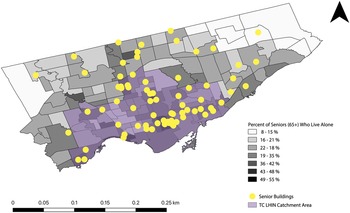

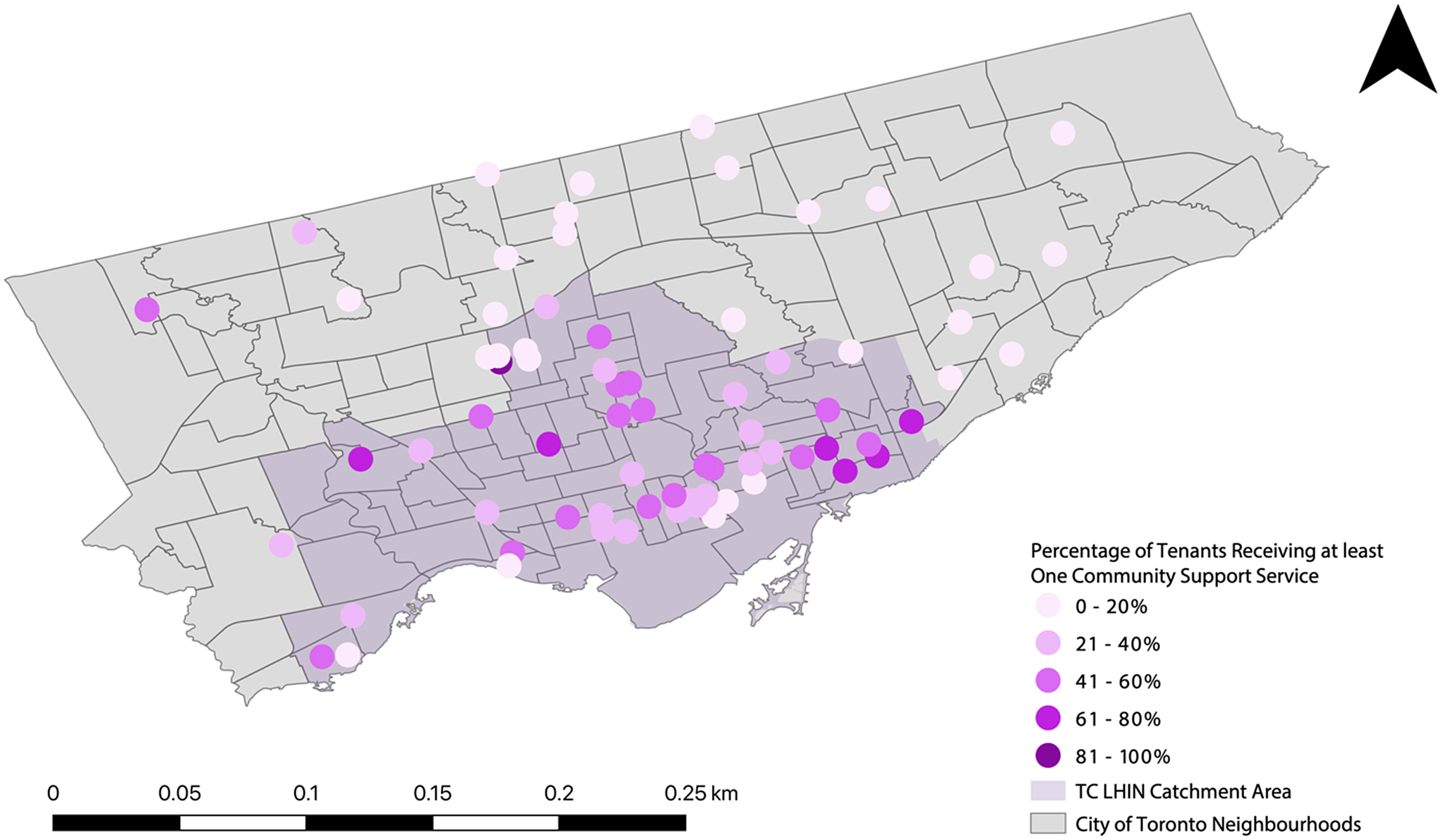

Finally, geographic Information Systems (GIS) mapping was used to visualize how community support service provision varied across buildings. The geographic coordinates for each TCHC seniors’ building were sourced from the City of Toronto’s One Address Repository data set available on the City of Toronto’s Open Data Portal (City of Toronto, 2021a). To visualize community support service provision across buildings, a geographic coordinate point was designed visually by shape and/or colour to represent service provision at that specific building. The mapping and analytical software, ArcGIS Desktop, was used to visualize the results.

Results

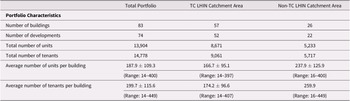

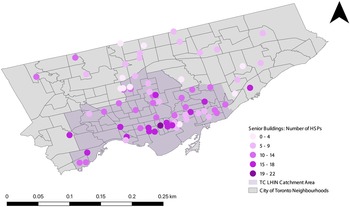

The 83 TCHC seniors’ buildings are scattered throughout the City of Toronto (see Figure 1), with many buildings located in neighbourhoods with a high percentage of older adults who live alone. Buildings included a mix of low-, mid-, and high-rise buildings ranging in size from 14 to 400 units (see Table 1). Fifty-seven buildings (represented by 52 postal codes or “developments”) fell directly inside the TC LHIN catchment area, while 26 buildings (represented by 22 postal codes or “developments”) were in other LHIN boundaries.

Table 1. Overview of building characteristics

Figure 1. Location of the seniors’ buildings and proportion of seniors who live alone by city of Toronto neighbourhood.

Service Provision Overview

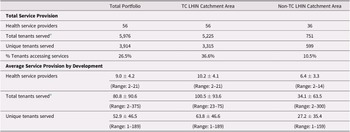

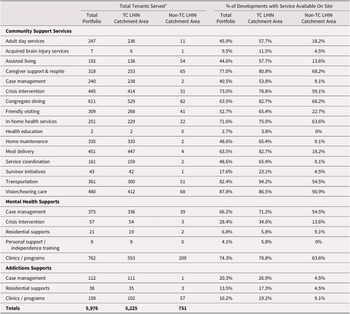

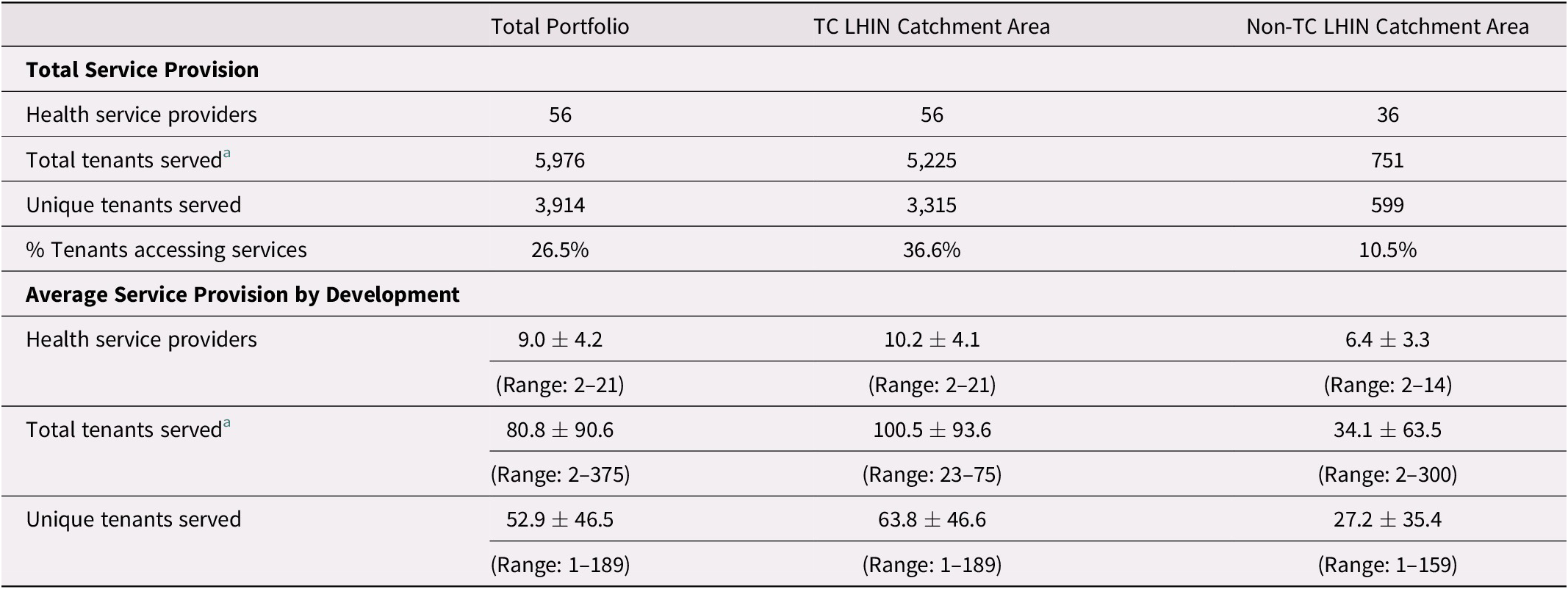

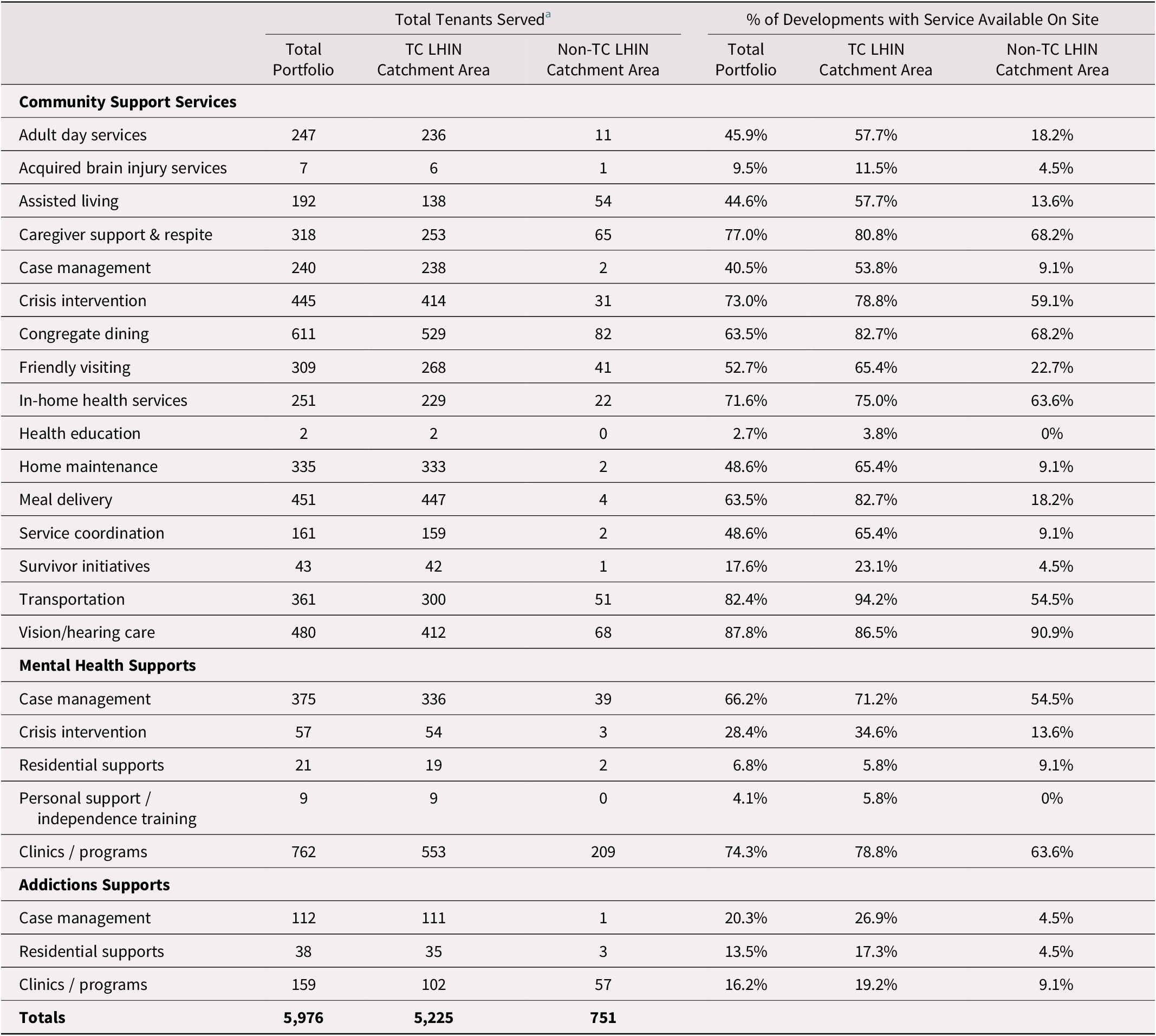

A total of 56 different community support service agencies provided services to 5,976 older tenants; however, because some tenants received multiple services, this actually represented a total of 3,914 service users (see Table 2). Although most of this service provision was for older tenants who lived within the boundaries of the TC LHIN, 36 agencies still provided 751 community health services to 599 older tenants living outside this catchment area. For those developments within the TC LHIN boundaries, larger buildings tended to have more services, as building size was positively correlated with number of service providers, service types, service units, and unique clients served. Neighbourhood characteristics, however, were not correlated with community support service provision (see Table 3).

Table 2. Overview of service provision

Note.

a Total tenants serviced reflects the number of tenants receiving each service and includes multiple enrollments.

Table 3. Correlations between community support service provision and building and neighbourhood characteristics for developments in the TC-LHIN region (n = 52)

Note.

a Percentage of people in private households in low-income status according to the Low-Income Cut-Off (LICO; after tax)

+ p < 0.07; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

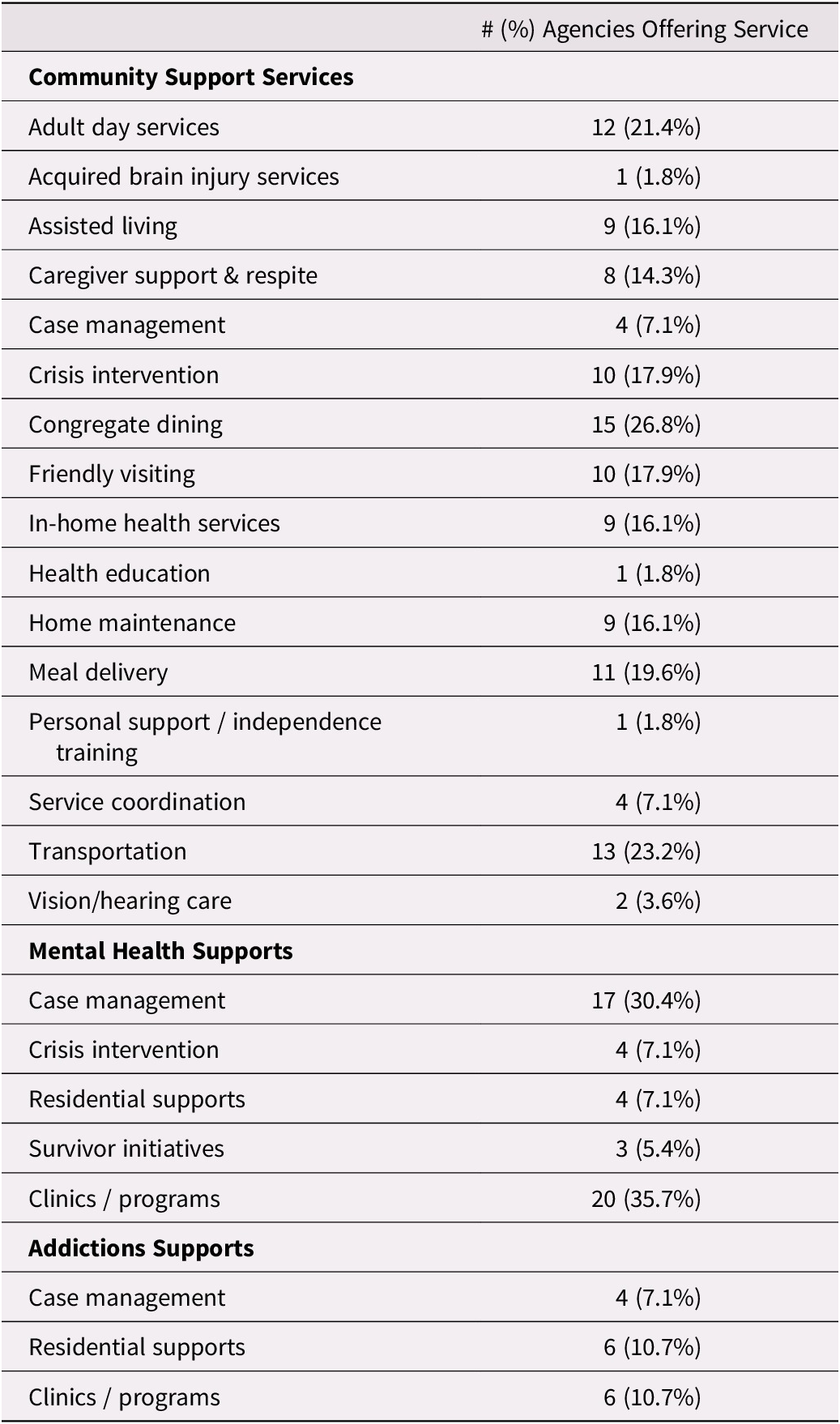

Scope of Services

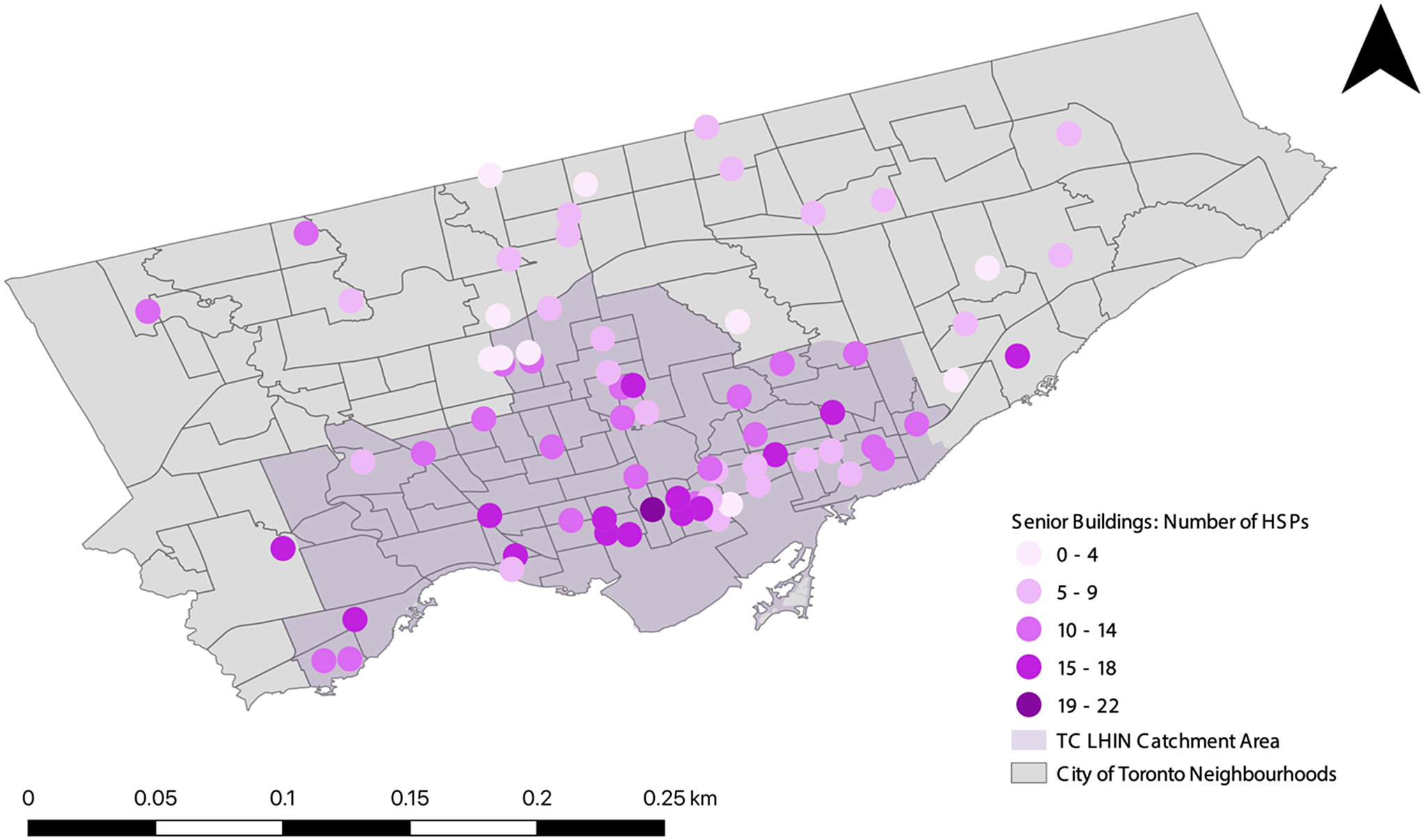

The number of service providers operating in each development varied widely (see Figure 2). Within the TC LHIN catchment area, each development had an average of 10 agencies providing services; however, three developments had fewer than 5 agencies providing supports for tenants, while one had 21 agencies operating on site.

Figure 2. Number of health service providers (HSPs) providing community support services by building.

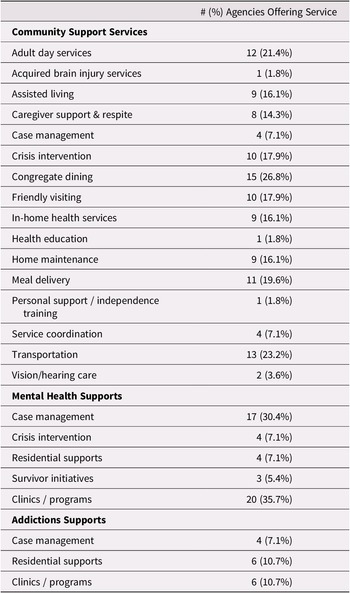

The scope of services available from these agencies was also mixed (see Table 4). Some community support services, such as transportation, meal delivery, congregate dining, friendly visiting, day services, and crisis intervention were available from at least 10 different agencies. Mental health supports, including primary care clinics and case management, were also widely available from multiple agencies. Other supports such as assisted living services, in-home health care, home maintenance, caregiver support, service coordination, and addictions support were less widely available across agencies.

Table 4. Number of community support agencies offering each type of support

Six community support service agencies offered a full menu of community supports and mental health programs and provided 40.1 per cent of all the services received by tenants. The general service area for these six agencies is shown in the Supplementary figure; these organizations were the lead agency (that is, the agency providing the most service in the building) for 33 developments (28 within the TC LHIN catchment area). On the other hand, there were a subset of agencies that had a limited scope of service but reached a significant number of tenants, such as the Alzheimer’s Society (which only provides caregiver support and service coordination), the Canadian Hearing Society (providing deaf and hard of hearing care services), and the Canadian National Institute for the Blind (providing vision impaired care services). Despite the limited scope, these agencies were leads in 15 developments (8 within the TC LHIN catchment area), and across the full portfolio, they provided 979 services, representing 16.4 per cent of all services provided.

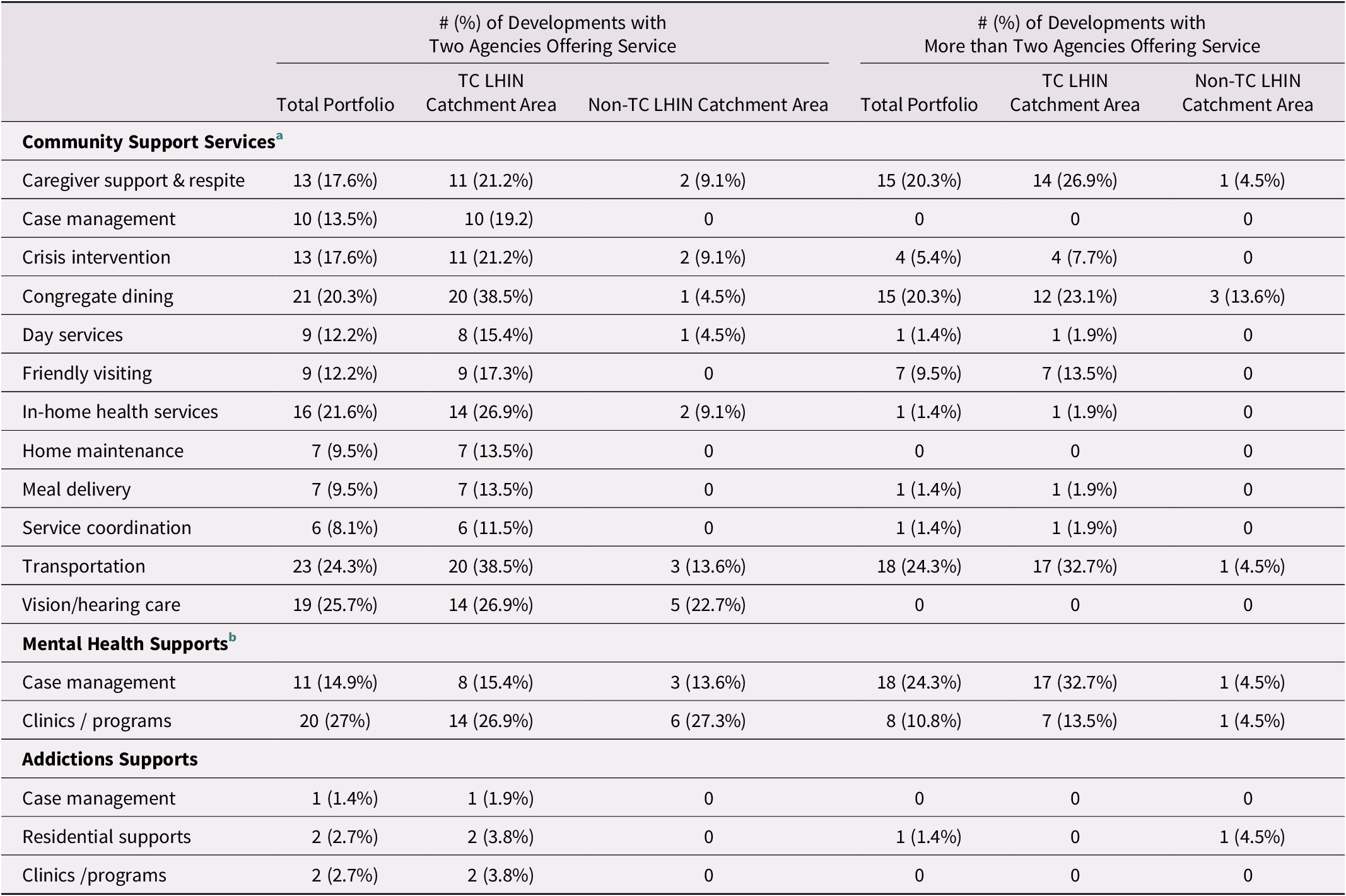

Access to Services

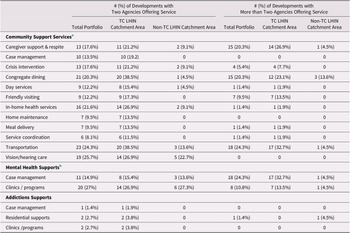

Congregate dining programs, meal delivery, hearing and vision care services, and crisis intervention were the most widely accessed services (see Table 5). Supports for mental health were also common, including case management and primary care clinics/programs. Many developments were supported by two agencies providing the same service (see Table 6); however, in the case of widely used programs, up to one third had three or more agencies offering duplicative services. For example, four buildings had transportation services provided by four or more agencies, and seven had congregate dining programs from four or more agencies. Mental health services were also frequently duplicated, with primary care clinics/programs and case management being provided by multiple agencies in the same location.

Table 5. Access to services

Note.

a Total tenants serviced reflects the number of tenants receiving each service, and includes multiple enrollments.

Table 6. Duplication of service provision across developments

Note.

a Assisted living services, health education, personal support / independence training, survivor initiatives and Acquired Brain Injury (ABI) programs were not offered by multiple agencies within a single development.

b Crisis intervention and residential supports were not offered by multiple agencies within a single development.

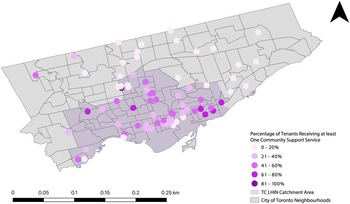

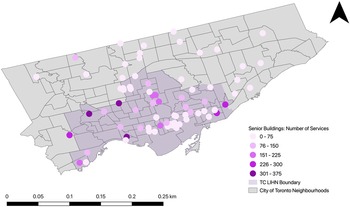

The proportion of tenants receiving community support services varied across locations (see Figure 3), with some having as little as 1.5 per cent of tenants accessing services, and others having up to 100 per cent of tenants accessing services. For most developments within the TC LHIN catchment area, however, between 20 and 60 per cent of tenants were linked to at least one community support service. Despite the fact that a sizeable proportion of tenants within each building were linked with a service, Figure 4 shows that the number of services that these tenants received is quite low for most buildings.

Figure 3. Percentage of older adult tenants receiving at least one community support service by building.

Figure 4. Number of community support services provided within each building.

Discussion

Access to appropriate community support services is critical for helping older adults in social housing age in place for as long as possible (Bigonnesse & Chaudhury, Reference Bigonnesse and Chaudhury2019; Locke et al., Reference Locke, Lam, Henry and Brown2011). TCHC has been working collaboratively with the City of Toronto and the TC LHIN to enhance access to services for older tenants living in the 83 senior-designated buildings (City of Toronto, 2019). We used data from the TC LHIN to describe baseline levels of service provision within these buildings, including what types of community support services older tenants were accessing, which organizations are providing these services, and how access to services varies across buildings. Given that there has been little research in the past decade on access to community support services among low-income older adults in social housing in Canada, this study provides valuable information on current service levels and identifies several future research recommendations, as well as policy and practice recommendations, to promote access to these services.

Although there were 56 different agencies operating within the buildings (for an average of 10 per development), only about one third of older tenants (25.6% across the portfolio and 36.6% within the TC LHIN catchment area) were receiving any community support services. Furthermore, the number of services that individual service users received was low, which is consistent with other Canadian data showing low utilization rates of community support services among older adults (Sinha & Bleakney, Reference Sinha and Bleakney2014; Strain & Blandford, Reference Strain and Blandford2002). Although it is possible that these low utilization rates reflect a lack of need for services, older adults in social housing are known to experience high rates of physical, mental, and social health challenges (see Sheppard, Kwon et al. Reference Sheppard, Kwon, Yau, Rios, Austen and Hitzig2022 for a review) that can be supported with community support services (Kuluski et al., Reference Kuluski, Williams, Berta and Laporte2012; Mah et al., Reference Mah, Stevens, Keefe, Rockwood and Andrew2021). Detailed health information on older adults living in the seniors’ designated buildings is unfortunately not currently known; however, tenants living in these buildings are thought to be amongst the most vulnerable and marginalized in the city (City of Toronto, 2019). Among all tenants in TCHC, most are low-income (with a median income of $18,398 per year); 29 per cent live alone and 22 per cent speak a language other than English (Toronto Community Housing Corporation, 2019). Furthermore, 43 per cent of households identify has having at least one member with a disability, and 40 per cent have at least one member with a mental health concern (Toronto Community Housing Corporation, 2019). Therefore, it is likely that low utilization reflects a need for new strategies to help tenants become aware of and access services that they might benefit from. Future research is also needed to better characterize the health and social care needs of older tenants and to better understand how the current level and nature of service providers meets (or does not meet) those needs.

Previous research shows that partnerships between local service agencies and social housing providers have been successful at bringing a variety of services on site for older tenants, including community supports such as home care, transportation, meal preparation, and housekeeping, as well as mental health services (see Sheppard, Kwon et al., Reference Sheppard, Kwon, Yau, Rios, Austen and Hitzig2022 for a review). Similarly, our study found that there were a handful of services that were available in more than 80 per cent of the buildings, including caregiver support, congregate dining, meal delivery, transportation, and hearing/vision care. Although these were some of the most widely accessed services, they appear to be the most uncoordinated, with up to one third of developments having four or more agencies offering duplicative service on site. More research with these service providers is needed to understand why this duplication of service is occurring. A lack of coordination among service providers has been reported in other research with older adults in social housing, particularly when tenants make their own referrals, leading to inefficient, haphazard, and duplicative service provision (Schulman, Reference Schulman1996). It could also be that a single service provider may not have the capacity to meet the needs in a particular building, necessitating support from other agencies. Interestingly, other research on integrated care models within social housing buildings suggests that service providers face challenges coordinating services with other providers, particularly when there is no designated “lead agency” to coordinate the programs and services on site (Yaggy et al., Reference Yaggy, Michener, Yaggy, Champagne, Silberberg and Lyn2006). The feasibility of designating a lead agency, however, requires further exploration, as it may not be possible for a single service provider to take the lead within a given building because of limitations in various resource levels such as staff time, funding, and space within individual programs.

Recommendations to Increase Access to Services

Our findings suggest there is a need to enhance service integration and collaboration across sectors (Cheng & Catallo, Reference Cheng and Catallo2019; Kodner, Reference Kodner2009; Sheppard, Gould, et al., Reference Sheppard, Gould, Guilcher, Liu, Linkwich and Austen2022) to increase coordination of and access to community support services within a social housing context. As part of the new housing services model being developed for the seniors’ designated buildings, TCHC has created the position of senior services coordinator. A key function of this new staff member is to identify vulnerable tenants and make referrals to appropriate community support services to ensure successful tenancies (City of Toronto, 2019; Sheppard, Hemphill et al., Reference Sheppard, Hemphill, Austen and Hitzig2022). This is made possible through fostering better relationships with tenants. As this new staff person is designated to only one or two buildings, they have more opportunities to collaborate with tenants and establish relationships of trust (Sheppard, Hemphill et al., Reference Sheppard, Hemphill, Austen and Hitzig2022), which research shows is critical for helping tenants agree to share information about their health and ask for help from housing and health partners (Canada Mortgage & Housing Corporation, 2020). Although previous research shows that many social housing providers have already successfully implemented similar staff positions to support older tenants (Redfoot & Kochera, Reference Redfoot and Kochera2004; Schulman, Reference Schulman1996; Sheehan & Guzzardo, Reference Sheehan and Guzzardo2008), there are additional strategies that can be developed to foster success in this role.

Social housing providers should implement standardized processes for assessing needs, identifying appropriate referral pathways to services, and following up to assess whether supports were put in place, if they had an impact, and how needs evolve over time. Previous research has shown that only 15 per cent of social housing providers tracked significant changes in their older tenants’ health conditions, 27.9 per cent monitored changes in daily functioning, and 22.4 per cent monitored the receipt of formal services (Sheehan, Reference Sheehan1986), suggesting that there are opportunities to make these practices more widespread among social housing providers. A coordinated needs assessment process should be implemented to regularly assess unmet needs that may negatively impact tenancies, and for which supports could be provided (Schulman, Reference Schulman1996). This may include assessing needs related to activities of daily living, food security, homemaking and unit maintenance, finances, caregiver stress, and mental health and addictions struggles. This process of identifying needs and making referrals should occur in collaboration with the tenant, as previous research shows that this helps to improve uptake or acceptance of services (Canada Mortgage & Housing Corporation, 2020; Ploeg et al., Reference Ploeg, Denton, Hutchison, McAiney, Moore and Brazil2016; Ploeg, Denton, et al., Reference Ploeg, Denton, Hutchison, McAiney, Moore and Brazil2017). It is also recommended that the referral process should include follow-up activities to monitor if services were actually put in place and to assess whether additional services may be needed (Ploeg et al., Reference Ploeg, Denton, Hutchison, McAiney, Moore and Brazil2016).

Previous research shows that practitioners often rely on outdated information sources when making referrals for community support services (Ploeg et al., Reference Ploeg, Denton, Hutchison, McAiney, Moore and Brazil2016) and lack a clear understanding of what types of services are available and from which agencies (Ploeg et al., Reference Ploeg, Denton, Hutchison, McAiney, Moore and Brazil2016; Ploeg, Denton, et al., Reference Ploeg, Denton, Hutchison, McAiney, Moore and Brazil2017). Therefore, a centralized agency referral library may be an important tool for housing staff to access, as it could provide up-to-date information on the various agencies providing community support services in their neighbourhood, including what they offer and how to make a referral.

Presently, there are multiple agencies providing similar or duplicative services to older tenants within the same building; although this is likely for a variety of reasons (such as different referral points, differing eligibility criteria, and waitlist times), it does make it difficult for housing staff and tenants to know which agency to go to for support (Sheppard, Gould, et al., Reference Sheppard, Gould, Guilcher, Liu, Linkwich and Austen2022). New partnership processes would present the social housing provider with opportunities to align multi-service agencies to specific buildings and designate them as “lead agencies”, thereby improving resource utilization and the number of tenants served. This would help ensure that services are more evenly available throughout the portfolio. Furthermore, having a primary referral source for multiple community support services will make it easier for the seniors’ services coordinator to build a partnership with staff at that agency, which will facilitate greater opportunities to work together. For example, working with lead agencies would make it possible to host joint team meetings to discuss referrals, service gaps, cancellations of service, and further supports that may be needed to support tenants (Sheppard, Gould, et al., Reference Sheppard, Gould, Guilcher, Liu, Linkwich and Austen2022).

Finally, previous research shows that the biggest barrier to accessing community support services is lack of awareness (e.g., Calsyn & Roades, Reference Calsyn and Roades1993; Denton et al., Reference Denton, Ploeg, Tindale, Hutchison, Brazil and Akhtar-Danesh2008, Reference Denton, Ploeg, Tindale, Hutchison, Brazil and Akhtar-Danesh2010; Strain & Blandford, Reference Strain and Blandford2002; Tindale et al., Reference Tindale, Denton, Ploeg, Lillie, Hutchison and Brazil2011); and there are several opportunities that social housing providers can take to enhance awareness. For example, through partnerships with community support service agencies, buildings could host education sessions to teach tenants about the different supports that are available and the kinds of needs that those services can help with. This will be particularly important for supports that are less widely accessed within the buildings already, such as case management, assisted living services, and adult day services, which are currently only available in approximately half of the buildings. Although previous research shows that many older adults access information about available health and community support services through online resources (Denton et al., Reference Denton, Ploeg, Tindale, Hutchison, Brazil and Akhtar-Danesh2008; Hong & Cho, Reference Hong and Cho2017; Levy, Janke, & Langa, Reference Levy, Janke and Langa2015), digital access among older adults tends to decline at lower levels of income (Choi & Dinitto, Reference Choi and Dinitto2013; Statistics Canada, 2019) and lack of digital access among older adults in TCHC is a known barrier to accessing health information (Mersereau, Reference Mersereau2021). Therefore, providing information about these community support services via pamphlets and in-person education sessions will be critical to increasing awareness of these supports.

Study Limitations

This research has several limitations which must be considered. First, because of missing postal codes in the Community Business Intelligence database, it is likely that these data undercount the community health service utilization rates within each development. On the other hand, these data assume that each TCHC seniors’ development is exclusive to the postal code; therefore, it is possible that the client and service counts were augmented by non-TCHC seniors residing at neighbouring addresses (i.e., within the same postal code) who also access community support services. Second, this study only examined the provision of community support services funded by the TC LHIN. As shown in Figure 1, 22 developments (representing 26 different buildings) fall outside of the TC LHIN boundaries. Service provision was naturally far lower in buildings that fell within other LHIN jurisdictions; therefore, these data do not provide a complete picture of all government-funded community support services being provided to older tenants in the portfolio. Furthermore, tenants may access other community support services that are not coordinated through their local LHIN. For example, the City of Toronto offers homemakers and nurses services that provide light housekeeping, laundry, shopping, and meal preparation to low-income older adults across the city. Some older adults may also access supportive services through faith-based congregations (e.g., Cnaan, Boddie, & Kang, Reference Cnaan, Boddie and Kang2005), or for-profit agencies.

Finally, this study did not include data on units of service or the characteristics of tenants receiving (or not receiving) service. Therefore, it was not possible to examine how much of each service is provided to individual tenants (e.g., how many rides were provided for a tenant receiving transportation services) or which tenants are receiving these services. A recent scoping review identified several social factors that influenced the propensity and intensity of home-care services, including age, ethnicity/race, self-assessed health, housing problems, education, finances, living arrangements, and social networks (Mah et al., Reference Mah, Stevens, Keefe, Rockwood and Andrew2021). Access to services may also be impacted by racism (e.g., Rhee, Marottoli, Van Ness, & Levy, Reference Rhee, Marottoli, Van Ness and Levy2019), ageism and sexism (e.g., Chrisler, Barney, & Palatino, Reference Chrisler, Barney and Palatino2016), homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia (e.g., Emlet, Reference Emlet2016), and lack of services in one’s language of choice (e.g., Wang, Guruge, & Montana, Reference Wang, Guruge and Montana2019). Therefore, future research should more directly examine the influence of these factors on community support service provision, which may identify other strategies to overcome barriers to access.

Conclusions

Access to community support services is critical for helping older adults remain safely in their homes for as long as possible. Study findings shed light on the types of services that low-income older adults in social housing are accessing, but suggest variable access to services across buildings. This understanding can be used to develop purpose-built structures to increase integration of housing and community support services to promote successful tenancies.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980822000332.

Funding

This work was supported by Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (PIDN [NHS 9-11] to S.L.H. and A.A.). The views expressed are of the authors and the funding entity accepts no responsibility for them. C. L. S. is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Fellowship in Research & Knowledge Translation in Urban Housing and Health (RAT-171349).