1 Introduction

One of the cruxes of English historical lexicography in the field of religious loans is the seemingly radical reorientation of lexical borrowing strategies between Old English (OE) and Middle English (ME): while the former period seems to be characterised by lexical pattern replication displayed in semantic extensions and various kinds of loan translations and formations, the later period is more straightforwardly one of matter replication (see Käsmann Reference Käsmann1961: 6). In the religious domain, not only individual lexemes but also whole word families may undergo semantic transformation and lexical replacement. For example, such core lexemes as gospel or Easter compete with evangelium and pasque and eventually survive, while dozens of other old religious terms are replaced with newer loans: fulluht by baptism, leorningcniht by disciple. Some of them, such as hǣlend ‘Saviour; Jesus’ become obsolete already by c.1250, while others, such as dryhten ‘the Lord’ linger until c.1500. Just how this competition is resolved in early Middle English is the focus of the present article.

My departure point is Hans Käsmann's (Reference Käsmann1961) study of church vocabulary in early Middle English, which offers both an exceptionally detailed account of lexical replacement and growth in several subdomains of religious lexis and a meaningful sociolinguistic introduction to important developments within the language and language-related practices after the Norman Conquest and up to 1350. I further rely on the electronic resources of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), the Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary (HTOED), the Dictionary of Old English (DOE), the Middle English Dictionary (MED) and A Linguistic Atlas of Early Middle English 1150 to 1325 (LAEME) and analyse their data in the light of more recent research into social change within the church and educational system after 1066 (Orme Reference Orme1973, Reference Orme2006). By applying the sociolinguistic frameworks of social networks, communities of practice and discourse communities (Timofeeva Reference Timofeeva2017, Reference Timofeeva2018), I connect lexical innovation to changing patterns of school education, i.e. the increasing importance of cathedral schools and of French as the language of instruction, and to changing patterns of preaching, i.e. the spread of the mendicant orders in the thirteenth century. The argumentation of this article is based on four premises: (i) that religious lexis should be divided into common terms and professional terms; (ii) that OE word frequencies can predict the survival of lexemes into early ME; (iii) that several individual instances of lexical innovation can be observed in largely the same geographical regions; and (iv) that lexical innovation in the religious domain is part of the more general social innovation of the early to mid thirteenth century triggered by the decisions of the Fourth Lateran Council (1215) and the spread of the mendicant orders in England in the 1220s (see also Ingham, this volume). These central points will be explained in the course of the article and illustrated with examples and maps; a few important exceptions will also be addressed.

1.1 Previous research on religious vocabulary in early Middle English

While there are many studies that address lexical growth and lexical loss in the ME period (Dekeyser Reference Dekeyser, Kastovsky and Szwedek1986; Chase Reference Chase1988; Dekeyser & Pauwels Reference Dekeyser and Pauwels1990; Coleman Reference Coleman1995; Durkin Reference Durkin2014 among others), Hans Käsmann's monograph on religious vocabulary in early ME remains the most comprehensive diachronic study that approaches this particular domain from an onomasiological perspective and reconstructs developments within individual semantic fields. Käsmann lists a total of 22 scenarios that are possible for religious lexis during the period between 1100 and 1350 (Reference Käsmann1961: 34–7): 4 of them concern native English vocabulary and 18 Romance loan vocabulary, mainly French loanwords. In the first category, he talks about: (i) lexemes with ‘constant’ semantics that stay so in ME (bishop); (ii) lexemes with less constant semantics that undergo semantic change in ME but nevertheless remain in use (belief and truth after the introduction of faith); (iii) lexemes that die out and whose place is filled by loans prior to c.1350; and (iv) lexemes that die out and whose place is filled by loans after c.1350. Similarly, in the second category (Romance loans), Käsmann gives a combination of semantic and diachronic observations on borrowing: the lexemes are distinguished according to whether or not they express new cultural concepts (friar, pardon), have stable, ambiguous (love vs charity) or obsolescent (givernesse vs gluttony) English counterparts, or belong to a lexical field together with other etymologically related Romance terms (prophecy, prophesy, prophet). A number of categories also relate to the discourse and poetic functions of the loans, such as their use as swear words (deu in depardeus or parde) or use chiefly in rhyming positions (omnipotent, virginity).

Among these lexical scenarios, I am primarily interested in those that involve native-based formations (loan translations and semantic loans) which were borrowed and established in the OE period, but later on, came to be replaced by French and Latin direct loans. Such examples can be found throughout Käsmann's book. The bulk of his analysis of church vocabulary consists of a series of case studies grouped into several categories of religious terms and their lexical fields: terms that denote the deity and trinity; heavenly hierarchy (angels, saints, prophets, etc.); faith and Christianity; heresies, paganism and hell; passion and martyrdom; grace, mercy and forgiveness; salvation, bliss and glory; the sacraments; virtues; sins; clergy and church hierarchy; monks and monasticism; and religious feasts. Each item is accompanied by a brief account of its origins in OE or another source language, a description of ME developments and a few examples of usages in ME texts. If a native-based term happens to be replaced by a French (more typically) or Latin one, or, exceptionally, the other way round, Käsmann speculates on the possible reasons and scenarios to explain why and how this could have taken place.

As this detailed cataloguing of subdomains and diachronic developments suggests, individual word and subdomain histories are in many respects self-explanatory and self-sufficient for Käsmann. Although his book opens with a helpful general discussion of the sociolinguistic (as we would now call it) situation of the early Middle English period, which gives a thorough state-of-the-art survey of lexicographic research up to the late 1950s and expresses a well-founded dissatisfaction with the uncritical treatment of all French loans in the literature as necessarily political-dominance and cultural-prestige related, the mass of the book addresses a different problem. Käsmann laments the disproportionate attention that was (and still is sometimes) paid to the growth of the English lexicon through borrowing and the neglect of native vocabulary and the history of its survival into the Middle English and also later periods (Reference Käsmann1961: 19–21). His response to this problem is laudable and monumental – his thesaurus-like monographFootnote 1 is exhaustive in its treatment of the semantic fields of native and borrowed religious terms, and the question of what happens to individual words and how the changes occur is answered from within the language system with remarkable precision. However, the societal dimension is largely missing in the practical chapters, and the book ends without a summary or conclusion.

Although a lot has been done to enrich our understanding of individual word histories in the ME period since 1961 (as the bibliographies in Sylvester & Roberts Reference Sylvester and Roberts2000 and Heidermanns Reference Heidermanns2005: §34 show), it is only more recently that we have developed a better vision of the sociolinguistic interplay between English and French and, in particular, of the status and sustainability of French in medieval England (Rothwell Reference Rothwell1998; Trotter Reference Trotter2003; Wogan-Browne et al. Reference Wogan-Browne, Collette, Kowaleski, Mooney, Putter and Trotter2009; Ingham Reference Ingham2012; etc.), and have begun to apply sociolinguistic tools to the history of the medieval English lexicon (Lenker Reference Lenker2000; Timofeeva Reference Timofeeva2017, Reference Timofeeva2018). This study aims to take up these new frameworks and relate the changes within religious vocabulary to the social networks of the clergy and especially to weak ties between the clergy and the laity.

1.2 Data and method

The question of why some OE religious terms survive and others become obsolete is in this article answered from the point of view of word frequencies. It is shown that words with 500+ occurrences in the Dictionary of Old English Corpus (DOEC) have a much better chance of being used in ME, and even today, than those with lower frequencies. This, in turn, is connected to the spread of religious vocabulary beyond professional usage to lay English-speaking communities at large. A selection of such terms is considered in detail against the case studies in Käsmann (Reference Käsmann1961), first and last attestations in the OED and MED, and onomasiological data in HTOED.

The raw data for this study come from the DOE, A to H (52 headwords with 500+ frequencies), based on the DOEC corpus files of over 3 million words and LAEME, 1150–1325, with a total word count of c.650,000 words. The advantage of using an atlas survey as an early ME corpus is that it allows a time-efficient analysis of text files, for which all the sources have been newly transcribed, and all words (excluding proper names) lemmatised and tagged. LAEME lexical searches can be mapped and cross-tabulated chronologically so that the geographical diffusion of new lexis and the obsolescence of the old can be illustrated visually. Inevitably, some shortcomings are associated with both resources: no mapping function is available for DOE or DOEC, while in LAEME, not all source texts are included in their entirety – from those that are over c.15,000 words long and survive in multiple copies, only samples were included by the compilers (Laing & Lass Reference Laing and Lass2007b: §3.1). Thus, establishing the geographical diffusion of lexemes prior to 1150 and obtaining complete counts of occurrences between 1150 and 1325 remains an impossibility. A few other technical problems are addressed in the relevant sections of the article.

2 Analysis

2.1 Old English frequencies as predictors of lexical survival

In my recent study of the diffusion of Latinate lexis in Old English (Timofeeva Reference Timofeeva2017), I argue that high-frequency loanwords are more likely to survive into the Middle English period. This applies, for example to god-spell with over 900 attestations in the DOE, but not to cȳþere ‘witness; martyr’ that occurs only c.100 times in the same corpus.Footnote 2 Although the limitations and under-representativeness of the extant Old English texts with their focus on religious matters and narratives have to be borne in mind (Timofeeva Reference Timofeeva2017, Reference Timofeeva2018), the number of occurrences in Old English is typically a good predictor of the survival chances of individual lexemes into the later periods. For the present study, to verify this point further, I solicited the assistance of the DOE team to generate a list of religious words that are attested more than 500 times in the DOEC.Footnote 3 As the lemmatisation of the corpus is still an ongoing process, the list that I obtained contains headwords only from A to H (table 1). Nevertheless, generalisations about the Old English lexicon are possible even at this incomplete stage. I reproduce the list here, in descending order by number of occurrences. Each headword is provided with a definition in modern English and the date of last attestation (if obsolete) according to the OED and MED (if the datings differ).

Table 1. Old English headwords with 500+ occurrences (based on DOE, A to H)

Even though table 1 gives only a crude picture of high-frequency religious lexemes, with many of them being polysemous and the frequencies of the individual senses subsumed under general counts, it demonstrates unequivocally several important facts about the surviving record of Old English:

• religious lexis constitutes a large portion of high-frequency content words (for comparison, only function words hē, hēo, hit, pron. (taken together, 200,000 occ.), and, conj. (172,000), and bēon, v. (100,000) have higher counts than god, n. (33,000); only cweþan, v. (17,500) and habban, v. (12,700) have frequencies higher than 10,000; between 10,000 and 5,000 we find dæg, n. (9,100), ān, num./pron. (9,000), for, prep./conj. (9,000), dōn, v. (8,900), cuman, v. (8,600), cyning, n. (8,000, with many of those probably being used in the religious sense too), be, prep./conj./adv. (7,600), æt, prep./adv. (6,000), būtan, adv./prep./conj. (5,600); between 5,000 and 1,000 we find hēr, adv. (4,100), gān, v. (3,700), hand, n. (3,700), hātan, v. (3,400), gear, n. (3,250), eald, adj. (3,000), faran, v. (2,600), gōd, adj. (2,500), hūs, n. (2,000), bōc, n. (1,750), drincan, v. (1,200), etan, v. (1,200), here, n. (1,150), full, adj. (1,100));

• the high counts of religious terms reflect the thematic imbalance of the Old English corpus;

• they have a high survival rate (all 52 lexemes are still attested in Middle English; 36 lexemes (or 69 per cent) survive into Present-day English);

• all native-based lexemes (42 out of 52, or 81 per cent) represent either semantic loans, with an extension from secular to religious or from pagan to Christian domain, or loan translations.

From these we can conclude that high frequencies in OE and survival rates in ME correlate and, further, speculate that high frequencies in OE would suggest diachronic, diatopic, diastratal and diaphasic diffusion of these general religious terms already in OE, although the unavailability of statistics per individual sense makes it difficult to trace the exact trajectories of diffusion. Some of these trajectories will be addressed below, as we continue from generalisations to concrete examples.

While it may seem natural and consistent with the observed tendencies that such terms as god and hālig should survive, it is far less straightforward that such terms as dryhten and hǣlend should die out. As the analysis of the first five high-frequency terms on the list will demonstrate, the stories of individual lexemes are more nuanced than the general counts would suggest, whether they belong to the survivor or the obsolescent category. It is both the former and, especially, the latter categories that merit closer attention.

With 33,000 occurrences in the DOEC (or c.10,880 per million words), god continues as the dominant religious term into the ME period. French-derived deus, deu and de are attested only as parts of swear words and interjections: parde, depardeus; deu merci, deuleset (Käsmann Reference Käsmann1961: 41).

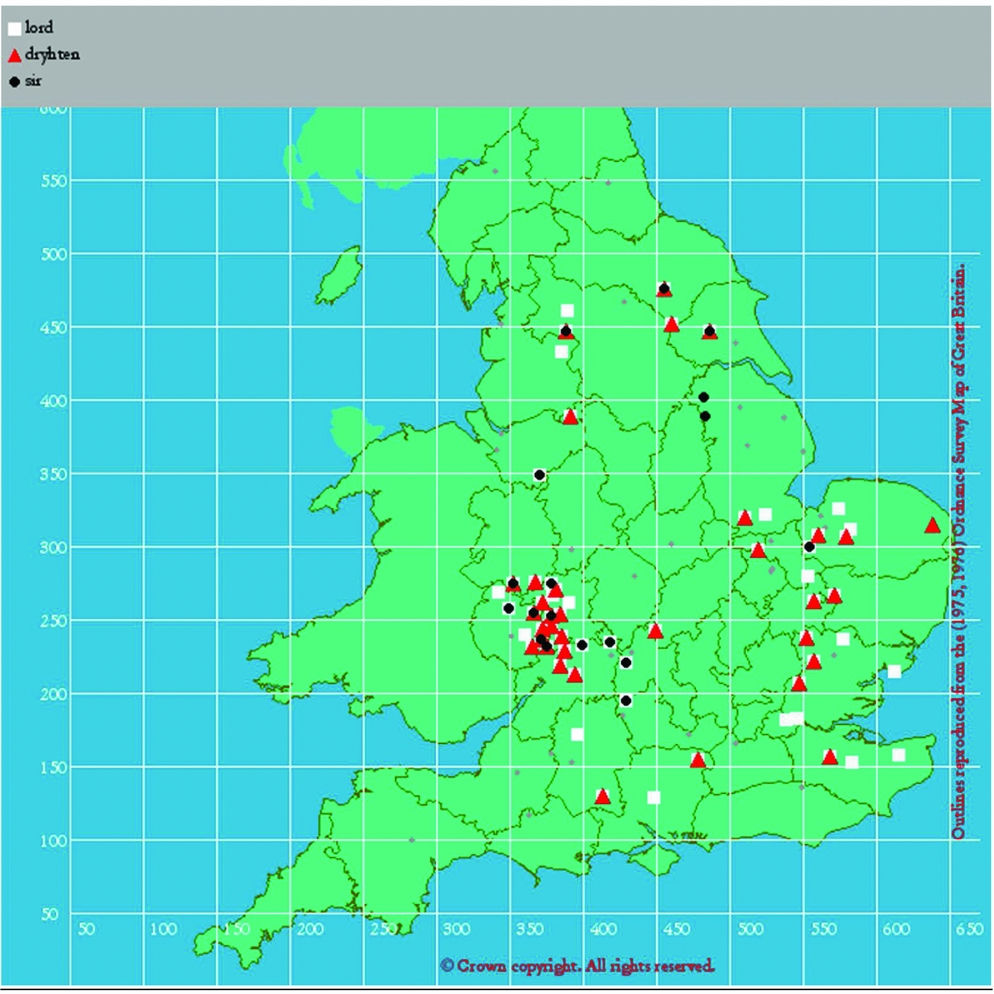

Although dryhten is the second most frequent religious word in OE (c.15,500 occurrences; c.5,110 per million words), its use drops already in early ME, but it only becomes obsolete towards 1500 (MED, s.v.). Apparently dominant in OE, dryhten encounters a powerful competitor in hlāford (c.1,400 occ.; c.462 per million words). In spite of its higher frequencies, the former is restricted to either poetry or, especially in late OE, to religious contexts, while the latter can refer to both ‘feudal lord’ and ‘the Lord’ without any genre or register restrictions. Käsmann relates the eventual demise of dryhten with its lack of semantic connection to the secular feudal world and its hierarchy (Reference Käsmann1961: 42). In LAEME the comparative distribution of the two lexemes becomes markedly different: lord scores 1,795 (c.2,767 per million words), while dryhten only 531 (c.818 per million words); moreover, sir(e) enters this semantic domain as early as c.1200 (Ancrene Riwle) and features 109 times in the corpus (of these only 23 are used as titles). Käsmann observes that the expansion of lord at the expense of dryhten is paralleled in the history of German: herro ousts truhtin as both ‘feudal lord’ and ‘the Lord’ (Reference Käsmann1961: 42–3). Although LAEME Maps function does not allow us to distinguish between the distributions of the sense ‘the Lord’ as opposed to ‘feudal lord’,Footnote 4 mapping the three lexemes seems nevertheless meaningful, especially considering that religious bias is present in LAEME Footnote 5 too (figure 1).

Figure 1. Geographical distribution of lord, dryhten and sir in LAEME

We can see that in many parts of England dryhten can still be used alongside lord and even alongside lord and sir. It serves very rarely as the only option, however, and alternation between dryhten and sir seems to be impossible. The innovation of sir is more pronounced in the West Midlands and the North, although the denser coverage for the West Midlands is a notorious problem in Middle English dialectology (Laing Reference Laing, Taavitsainen, Nevalainen, Pahta and Rissanen2000; Laing & Lass Reference Laing and Lass2007a: §1.3; Gardner Reference Gardner2014: 42–3; and discussion below).

Käsmann's observation that dryhten becomes obsolete in secular senses in all OE texts except poetry deserves closer consideration (Reference Käsmann1961: 42; the DOE s.v. dryhten points to the same conclusion). This would suggest that dryhten was a marked poetic, typically non-secular, term as early as late OE, which greatly reduced its survival chances into later periods. The German cognate truhtin seems to tell the same story. Perhaps it was precisely for their elevated connotations that these, probably archaic, terms were chosen or even reanimated in both languages. Diachronically, however, they were unable to resist the pressure of their unmarked synonyms.

The term that features third on the list, hālig, with 8,400 occurrences in OE (c.2,770 per million words), remains frequent in early ME: it occurs 1,476 times in LAEME (c.2,275 per million words) and is clearly dominant as an adjective (cf. only 3 attestations of the lexel saint as an adjective). hālig is never used with names of saints, however, this function being restricted to various reflexes of the Latin sanctus – sanct, sant, san, seint (tagged as a noun-title ‘n-t’ in LAEME, including abbreviations). The lexel saint is attested 1,164 times as a noun-title but only 22 times as a noun in its own right (cf. Käsmann Reference Käsmann1961: 62–4), in which function the reflex of the OE noun hālga (c.950 occ. in DOEC; c.313 per million words) is still more frequent – 88 attestations (c.136 per million words) in LAEME – becoming obsolete only after 1500 (MED, s.v. halwe). The functional distribution is thus apparent: hālig is used only as an adjective, hālga only as a noun, and the reflexes of sanctus are strongly preferred as titles.

Two nomina sacra come next on the DOEC list: crist (c.5,500 occ.; c.1,813 per million words) and hǣlend ‘Saviour, Jesus’ (c.5,000 occ.; c.1,648 per million words). crist is used 1,387 times in LAEME (c.2,137 per million words), typically in <crist> spellings, <ch> surfacing only in abbreviations. The history of the loan translation is much more complex, however.

Ælfric, who relied on the established vernacular tradition, grounded in the Gospels (Matthew 1.21), Jerome's Liber Interpretationis Hebraicorum Nominum and Isidore's Etymologies (vii.2), explained the meaning of the name Jesus as follows:

(1) Iesus is ebreisc nama. þæt is on leden Saluator. and on englisc Hælend. (ÆCHom II, 12.2 (122.420))

‘Iesus is a Hebrew name, that is in Latin Saluator and in English Hælend’

Accordingly, the collocation Hælend Crist for ‘Jesus Christ’ is extremely common in OE (over 500 occurrences, of these more than 200 in Ælfric). It is not limited to West Saxon, however, featuring also in the North, for example, in the interlinear glosses to the Lindisfarne Gospels, nor to the Bible and biblical commentary, occurring, e.g., in liturgical texts and charters.Footnote 6 The use of the name Jesus <Iesus, Ihesus> is, in contrast, very rare (cf. OED s.v. Jesus) and, for the most part, restricted to the explanatory passages, such as the one quoted in example (1). Although, when used on its own, Hælend is typically preceded by a demonstrative, its status remains somewhere between a common noun and a proper name. This is why its demise in early ME should be examined next to the rise in the use of both saviour and Jesus.

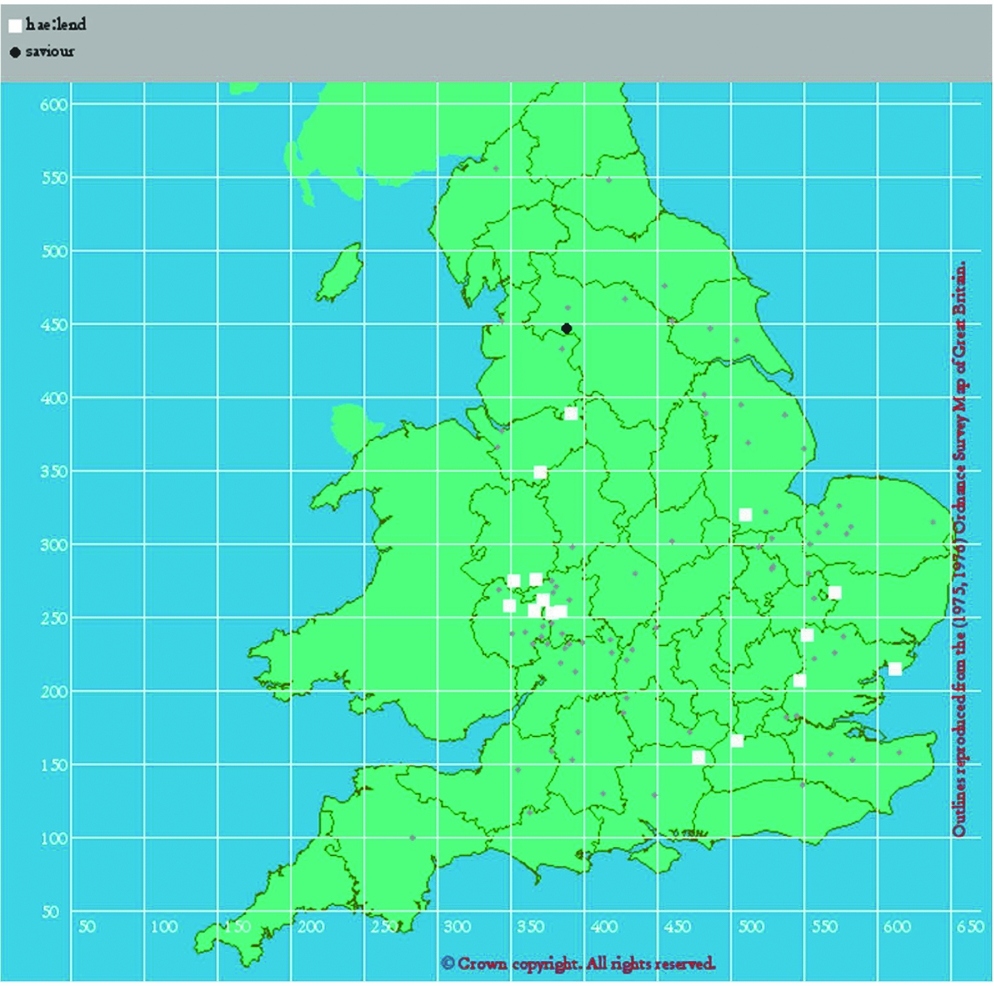

Unfortunately, mapping proper names is not possible with LAEME, as they are not treated as lexels, so figure 2 represents only those text languages that use Helend (148 occ. in 24 texts) and saviour (1 occ. in # 295, MS Cotton Vespasian A.iii containing a version of Cursor Mundi and other religious poems, dated to C14a). Thanks to the kind assistance of the LAEME team I was able to obtain a list of all proper names from the corpus.Footnote 7 I then manually selected all instances of Jesus and checked the files that contained it for date and localisation.

Figure 2. Geographical distribution of hǣlend vs saviour in LAEME

Although still more frequent in the late twelfth century (figure 3), its relative portion being just over 50 per cent compared to Jesus, Helend is probably construed less and less as a proper name, as the collocations with Christ are not numerous (seven altogether in 5 texts: ## 301, 1200, 1300, C12b2; # 184, C13; # 246, C13b1). Explanations similar to that given in example (1) above are also found in early homily collections, the Trinity (# 1200, C12b2) and Lambeth Homilies (# 2001, c.1200), which are well known for their close kinship with the OE homiletic tradition (Swan & Treharne Reference Mary and Treharne2000), e.g. in this commentary on the Creed:

(2) & in ihesum christum. and ich ileue on þe helende crist. filium eius unicum. his enlepi sune. dominum nostrum. ure lauerd he is ihaten helende for he moncun helede of þan deþliche atter. (# 2001, Morris 1868: 75)

‘& in ihesum christum. and I believe in Jesus Christ. filium eius unicum. his only son. dominum nostrum. our lord. He is called helende because he has healed mankind from the deadly poison.’

Figure 3. Relative frequencies of Helend, Jesus and Saviour between the late twelfth and early fourteenth centuries

It is illuminating that the scribe of # 2001 is still able to pick up the word play: healer/saviour who has healed/saved us from poison/corruption. The etymological relationship between the verb helen and helende crist was probably lost upon the scribe of # 1200, for he uses alesede ‘delivered, redeemed’ in his version of the commentary (cf. Käsmann Reference Käsmann1961: 154).

From the early thirteenth century, Jesus, typically in the form <Iesu> from French (Käsmann Reference Käsmann1961: 51; OED s.v. Jesus), if spelt out (28 per cent of occurrences), or in the form <IHU>, if abbreviated, gains increasingly more ground, ousting Helend completely by the end of the century. It is soon after this that Saviour is introduced from French. Käsmann connects the demise of Helend with its obsolescent morphology: indeed, all reflexes of OE agent nouns in -end die out in the course of the early ME period, e.g., alesend ‘redeemer’ or sheppend ‘creator’ (Reference Käsmann1961: 51). Although morphological unanalysability is an important concern, I would argue that its semantic and categorical arbitrariness was at least an equally valid factor. Again, we are dealing with a marked lexeme, with special connotations, belonging to a high register. Its juxtaposition with the verb heal (OE hǣlan), from which hǣlend was derived, is revealing. Its ME reflex hēlen is a polysemous and unmarked verb, which means ‘to cure, heal; become healed; reform, improve, save’ (MED, s.v.). As example (2) shows, these senses can still trigger an educated pun, which probably suggests that the connection between the verb and its derivative was no longer straightforward for more ordinary speakers, who could not easily associate a ‘healer, leech’ with ‘reformer, improver’ and ‘saviour’. The obsolescent morphological make-up of Helend made things even more ambiguous. Moreover, a special devotion to the holy name of Jesus that was developing in the thirteenth century under Franciscan influence (Renevey forthcoming), and the increasingly more expected practice of the recitation of the Creed and Articles of Faith by laymen (Reeves Reference Reeves2015), could have contributed to the marginalisation of Helend as a sacred name, making its usage in prayers archaic and unwanted.

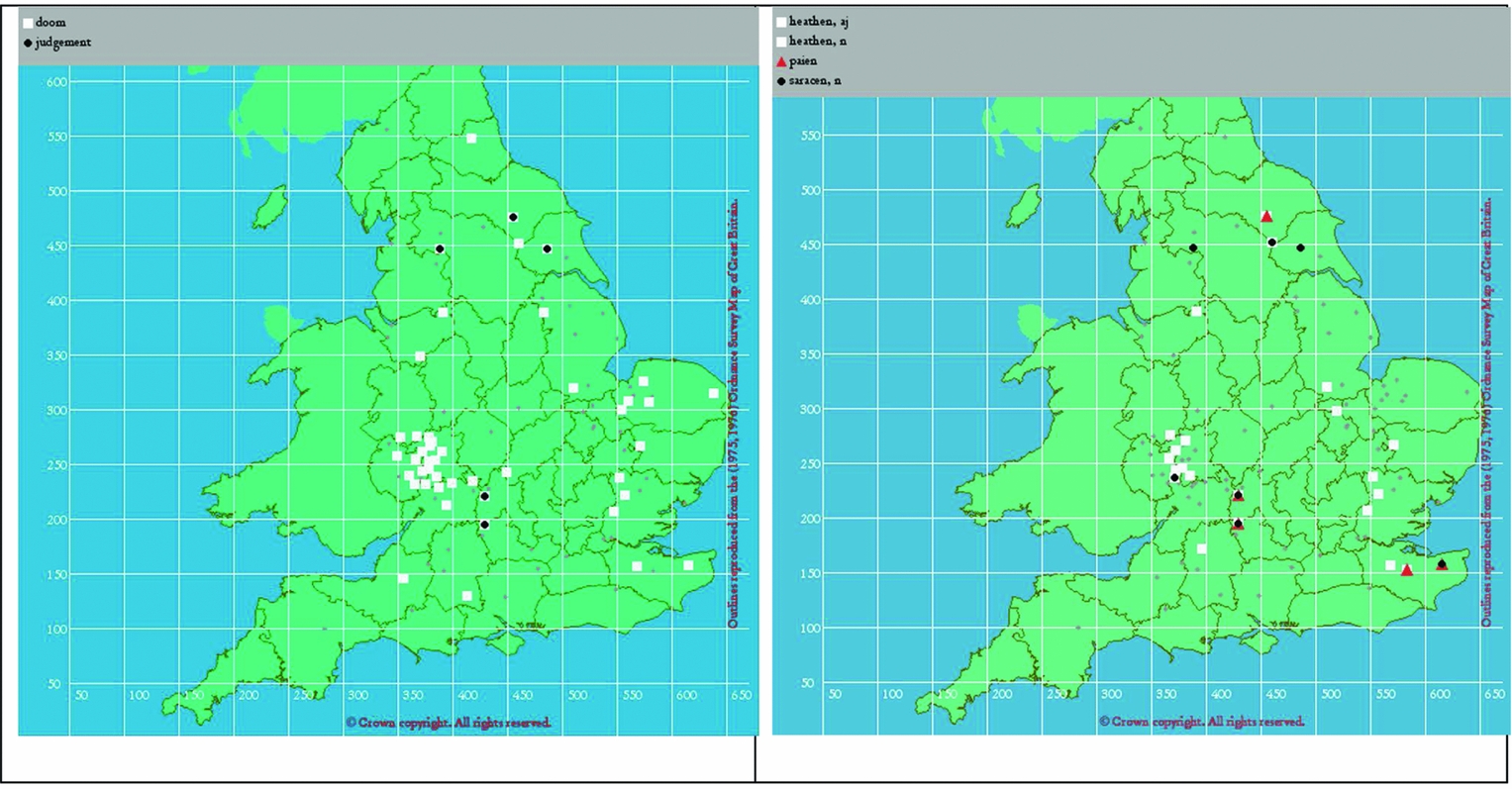

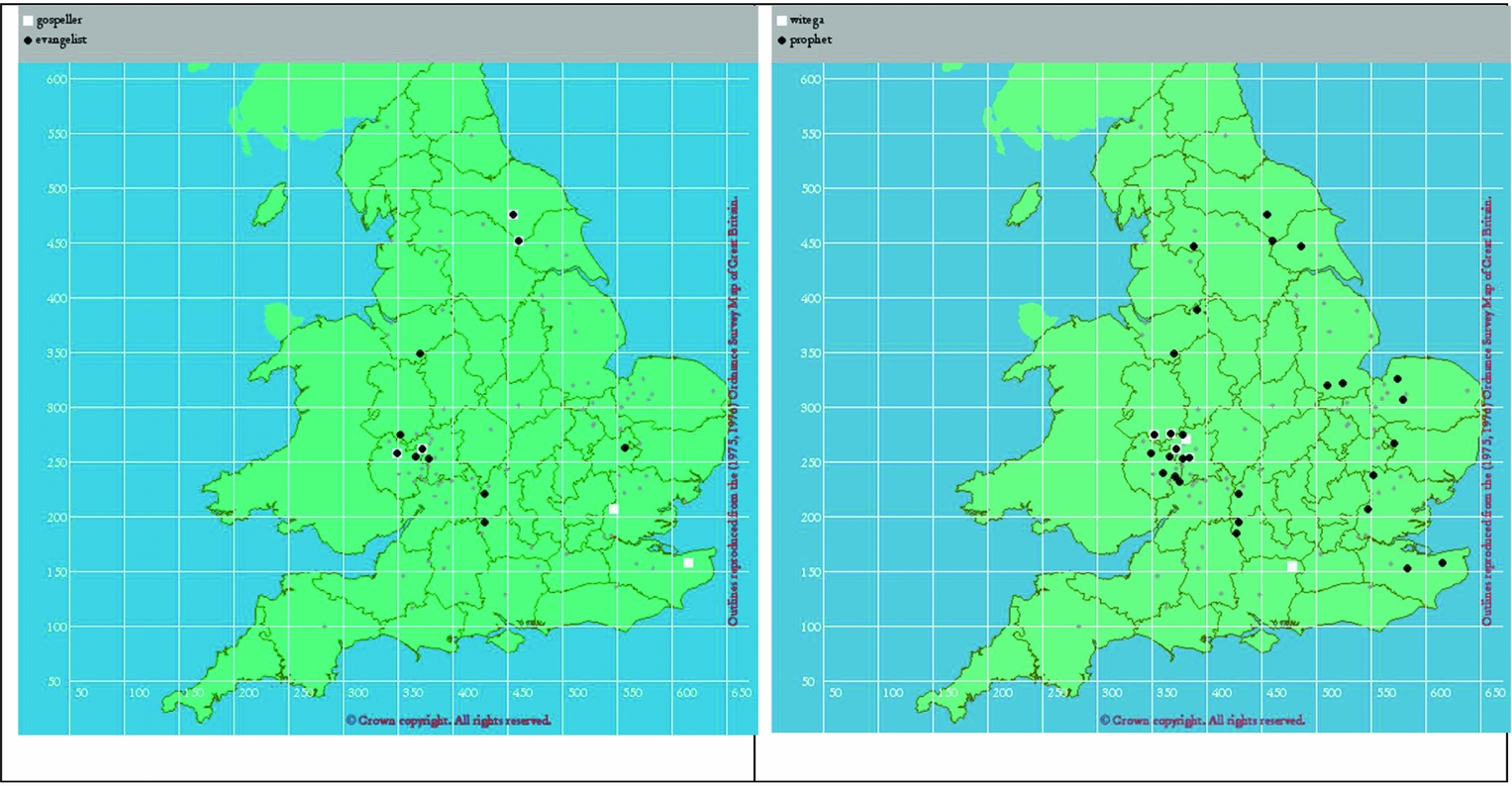

All in all, word counts in OE are a good predictor of survival in ME, provided high-frequency terms are unmarked in ME. This finding is illustrated by several maps: of doom (vs judgement) and heathen (vs paien and saracen), taken from the 500+ list (figure 4), and of god-spellere (c.270 occurrences in OE; vs evangelist) and witega (c.450 occurrence in OE; vs prophet) (figure 5).

Figure 4. Geographical distribution of high-frequency terms doom vs judgement (left) and heathen vs paien and saracen (right) in LAEME

Figure 5. Geographical distribution of lower-frequency terms gospeller vs evangelist (left) and witega vs prophet (right) in LAEME

My last illustration attempts to relate lexical change to social innovation more generally. We have seen in the case study of Helend that the changes introduced into devotional practices in the thirteenth century may have contributed to the demise of this lexeme. Likewise, we would expect ecclesiastical innovation to be reflected in the growth of the lexicon (explored more fully in section 2.4).

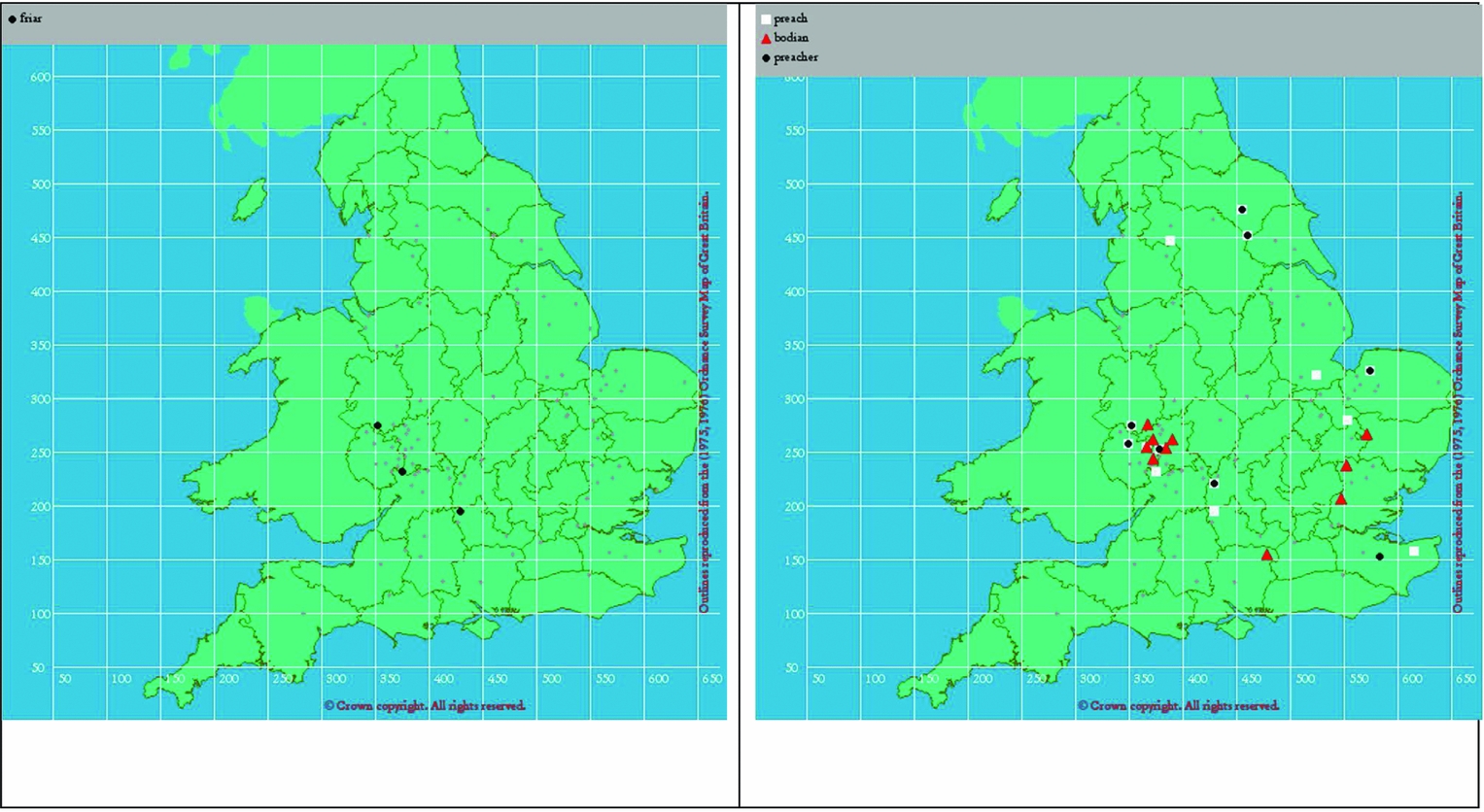

Figure 6 shows the geographical distribution of friar (22 tokens, attested from C13b2 on) and of to preach (89 tokens from C13a2 on), preacher (14 tokens from C13a2 on) as opposed to bodian ‘to preach’ (30 tokens until C13b2). As ‘friar’ was a new concept whose introduction into medieval English society had an immediate impact on the lexicon (Wenzel Reference Wenzel1983; Durkin Reference Durkin2009: 3–7), the expansion of preach at the expense of bodian from the second quarter of the thirteenth century appears to be closely related to the innovation of friar. The two lexemes can be pinned down to the same survey points in the West Midlands and South West, and their spread may have gone hand in hand in other regions too. It is quite possible that there was also a semantic association between the new style of preaching and the mendicant orders, while bodian and bodung, although expected of the parish priests, were taken as something different and gradually fell into disuse. The relation between social innovation, geography and lexical changes is explored in the remaining sections.

Figure 6. Geographical distributions of friar (left) and preach, preacher vs bodian (right) in LAEME

2.2 Maps explained in more detail

The distribution maps in figures 4–6 are not colour-coded for period and need more detailed explanation in relation to ME dialectology and its written record. The tendencies observed are directly related to the regional coverage of LAEME across subperiods of early ME. The word counts per subperiod and dialect area are available in Gardner's (Reference Gardner2014) study of ME derivation, which uses LAEME for the early period. Gardner divides corpus files into five subperiods of roughly forty years (Reference Gardner2014: 40; for the rationale and advantages of forty-year time frames, see ibid.: 40–1) and then cross-tabulates diachronic and regional data, distributing LAEME files into the traditional ME dialect groupings.Footnote 8 Her tables are reproduced here as tables 2 and 3.

Table 2. The division of LAEME into five subperiods (from Gardner Reference Gardner2014: 41)

Table 3. Regional coverage of LAEME across subperiods (from Gardner Reference Gardner2014: 43)

Texts from the West Midlands account for the majority of the corpus (c.43 per cent) and dominate numerically in EMidE II, EMidE III and EMidE IV. East Midland texts (c.22 per cent) are distributed more evenly across subperiods but predominate in EMidE I. The South West (c.13 per cent) is sufficiently covered only from EMidE III onwards, while the North (c. 10 per cent) and the South East (c. 6 per cent) increase in coverage only in EMidE V (percentages are taken from Gardner Reference Gardner2014: 42; for word counts per region, see ibid.). Regarding chronology, as we would expect, earlier texts up to c.1200 show more lexical affinity with the OE tradition. Thirteenth-century texts still largely respect OE lexical practice but also display new French terms; texts from c.1300 are increasingly more innovative. Not surprisingly, therefore, many conservative lexical features are observed in the East Midlands (this region providing most of the data for EMidE I) and parts of the West Midlands, while variation between old and new tendencies is typically more pronounced in the West Midlands (dominating EMidE II, EMidE III and EMidE IV), and lexical innovation shows up a lot in the North and South (northern and southern texts, taken together, outnumbering the Midlands in EMidE V, 78 per cent and 22 per cent respectively).

2.3 The West Midlands in the thirteenth century

Even a brief look at LAEME maps and survey points reveals that the West Midlands stands out where the density of coverage is concerned, especially in the north of the dialect area, which includes Gloucestershire, Worcestershire, Herefordshire and southern parts of Shropshire. This is hardly surprising since the intellectual prominence of this part of Mercia in the OE period and the continuity of its pre-1066 literary tradition have long been acknowledged by scholars (Bately Reference Bately, Kennedy, Waldron and Wittig1988; Millett Reference Millett and Edwards2004). For centuries before the Norman Conquest, these counties enjoyed a more intense and more protected cultural life (especially after the beginning of the Viking raids in the late eighth century) than other parts of England. Mercian scholars were instrumental during the Alfredian revival in the 890s, and the bishops of Worcester played key roles during the Benedictine reforms of the tenth century. After the council of Westminster (1070), when a number of English bishops were deposed and many vacancies had already been filled by the Normans, only a few episcopal sees were still administered by the people appointed during the reign of Edward the Confessor. Among them were Walter of Lorraine, bishop of Hereford (in office 1060–79) and Wulfstan, bishop of Worcester (1062–95). Wulfstan's authority was particularly important in the preservation of religious foundations and their archives in the region (Mason Reference Mason1990). Therefore, when the seeds of new methods and styles of preaching began to spread from the Continent in the second half of the twelfth century and especially after 1215, in the West Midlands, they fell on fertile soil. Historical interest in vernacular written texts, a concentration of old cathedral centres and new mendicant houses, the proximity to Oxford, and, critically, the bishops who were active in the pastoral reform, all contributed to the proliferation of literary production in English and the circulation of texts across the region (Millett Reference Millett and Edwards2004: 9–10). It is in this context that the Lambeth Homilies, Ancrene Wisse, the Katherine and Wooing collections were written and copied, and it is in this context that the Tremulous Hand of Worcester annotated OE manuscripts (Laing Reference Laing, Taavitsainen, Nevalainen, Pahta and Rissanen2000: 108; Franzen Reference Franzen1991, Reference Franzen2003).

Although the decisions of the Fourth Lateran Council provided a necessary impetus for the social changes that we observe from the 1220s onwards, i.e. a wider support for grammar schools at cathedral level that could provide basic education for the laity, the increasing availability of English texts for religious instruction and private reading, and the availability of preaching in English that we can deduce from this, the first indications of these developments are already present decades earlier at both legislative and executive levels. For example, canon 18 of the Third Lateran Council (1179) required every cathedral church to assign a schoolmaster to instruct the clerics of that church and children from poor families for free (Orme Reference Orme2006: 201–2). Similarly, the programme of popular preaching had been advanced and elaborated in the last quarter of the twelfth century by the great Parisian theologians Peter Cantor (d. 1197) and Alan of Lille (d. 1203). The influence of their doctrines can be seen in all texts of the AB language (Millett Reference Millett and Edwards2004: 9).

In 1215, a major programme of pastoral reform was launched. The decisions of the Fourth Lateran Council provided for instructors in Latin grammar and ‘in matters which are recognized as pertaining to the cure of souls’ to be appointed by all cathedral churches and other churches with sufficient resources (canon 11). Bishops were expected to recruit preachers to help them ‘minister the Word of God to the people’ in large dioceses and assist with ‘hearing confessions and enjoining penances’ (canon 10). At the same time, Christians of both sexes were obliged to confess their sins and receive the Communion at least once a year (canon 21). In response to this, ‘[t]he teaching syllabus evolved by the English bishops . . . required the laity to know and be examined on the Creeds, the Pater Noster, the Commandments and the Deadly Sins, sometimes supplemented by the Sacraments and later joined by the Ave Maria’ (Gillespie Reference Gillespie and Edwards2004: 129). It goes without saying that clerical instruction on such a universal scale had to be undertaken in the vernacular. The demand for popular preaching was answered by the existing cathedral and monastic structures, but even more so by the new mendicant orders that were making astonishing progress both on the Continent and in Britain. The Dominicans arrived in 1221 and established their first base at Oxford. The Franciscans followed suit in 1224 and made their urban settlements at Canterbury, London, Oxford and Northampton. By 1250 both orders already had dozens of foundations across the country, including Franciscan houses in Worcester (1227) and Hereford (1228), and Dominican houses in Shrewsbury (before 1232) and Chester (before 1236) (Bolton Reference Bolton, Szarmach, Tavormina and Rosenthal1998: 305; Millett Reference Millett and Edwards2004: 10). A well-known reformer, Robert Grosseteste, later also a Franciscan, was active in the diocese of Hereford between 1195 and 1220, and most of the bishops, active in pastoral reform in the West Midlands, were linked to him. Bella Millett observes,

It is possible that these bishops acted as catalysts for a revival of vernacular preaching and devotional literature in the West Midlands, introducing Paris-trained preachers familiar with new techniques and themes but also encouraging the repackaging of older native preaching resources for new purposes. (2004: 10)

A similar repackaging of older native lexical resources for new instructional purposes must have taken place: established frequent terms were preserved, while those associated with changing practices of, e.g., confession and penance, were replaced with French loans (Timofeeva forthcoming).

2.4 Reforms, lexical innovation and social networks

Establishing the exact connections between linguistic change and social change has been the principal task for historical sociolinguistics, at least since the 1980s (Milroy Reference Milroy1987; Trudgill Reference Trudgill2000; Labov Reference Labov2001; etc.). The finding that rapid and/or large-scale lexical innovation and, especially, adoption of loanwords are indicative of social change is hardly a surprising outcome in this investigation. What needs to be addressed therefore is the question of the social networks that allowed thirteenth-century lexical innovation to happen, the patterns and conditions that defined its speed.

The reform movement of the late twelfth to early thirteenth century can be seen as the major driving force behind the introduction of new Romance-based religious terms in Middle English. Innovative lexical tendencies are more observable in the West Midlands because the initial stages of the new social developments and textual attestation were also more pronounced in this region. At the same time, both Midland areas show a stronger connection to the OE written tradition and its religious vocabulary.

With grammar-school education being typically available via the French medium, the higher schools and universities functioning in both Latin and French (Orme Reference Orme1973: 71–8; Ingham this volume), and Francophone schoolmasters and friars being more readily present in urban centres, we would expect lexical innovation to diffuse in episcopal and university cities and other large and rich towns that maintained grammar schools. Those immediately affected were the children of the nobility and social climbers who attended these schools (see Richter Reference Richter1979), but public preaching could also reach much broader audiences. Friars, Franciscans in particular, more mobile and resourceful, were trained to preach in a variety of situations – in ‘the cloisters, market squares, gardens, preaching crosses and other open places; . . . at fairs’ – and in more than one language – ‘in the vernacular, French and Anglo-Norman with Latin as the medium for clerical and scholastic congregations’ (Robson Reference Robson2017b: 20). Because friars created their own system of school and university education (O'Carroll Reference O'Carroll1980; Bolton Reference Bolton, Szarmach, Tavormina and Rosenthal1998), they were less dependent on the old written tradition in general and freer to generate new linguistic norms. In the latter process, common English terminology was naturally preserved, while rare and ambiguous terms were rejected. Considering that many friars travelled a lot both locally and across the country, it is easy to envisage how their French-influenced linguistic practices would spread together with them through preaching, charity work and spiritual ministrations. Moving easily among people of any social standing (Robson Reference Robson2017a: 456–7), they would also provide the necessary weak ties for the diffusion of new religious lexis both within and across social classes, including the very low and marginalised. Given the extent of their geographical and social mobility and the extent of multilingualism and language fluency expected from them, it is understandable why the introduction of French terms was often preferable to the reanimation of old or the creation of new lexical items in English. Not only could it facilitate less taxing code alternation between English, French and Latin on the part of the preachers, but it also allowed for a kind of lexical standardisation across the three (and possibly more) codes, if important terminology could be kept ‘stable’, that is to say, Romance.

3 Conclusions

The religious terminology inherited from the Old English period falls into two categories: (i) established terms that had belonged to the West Saxon standard and were still preserved in general use after 1066 among the lower regular clergy, parish priests and the faithful at large, and (ii) terms of limited currency that had failed to spread outside local communities with strong ties and monastic usage, and survived for some time in smaller religious foundations. The OE word counts are normally a safe predictor of whether a particular lexeme belonged to one or the other category, with many local norms becoming obsolescent already in OE.Footnote 9 In rural communities, the general type probably sufficed for a long time, but urban communities were more ambitious and more exposed to new types of religious instruction, Francophone clergymen, and the fruits of education in general (see Millett Reference Millett and Edwards2004: 13).

Lexical innovation in the religious domain was largely brought about and conditioned by the new standards and styles of preaching and new devotional practices that began to develop in Europe in the late twelfth century and gained momentum in the 1220s and 1230s. In the thirteenth century, the rate of lexical growth was unprecedented (Dekeyser Reference Dekeyser, Kastovsky and Szwedek1986) and the rate of semantic expansion was the highest in the ME period (Coleman Reference Coleman1995). Preachers of the new type were the multilingual innovators who generated new lexis in English and at the same time were instrumental in its diffusion, serving as weak ties between the various levels of the medieval society. Urban middle classes were the most likely English-speaking early adopters of new norms, as they often had productive competence in French (Richter Reference Richter1979), although not necessarily in ecclesiastical French, while lower urban and rural classes would adopt new norms at a later stage, their competence in ecclesiastical English being probably receptive rather than productive (see Ingham, this volume) but activated often enough in church and other public places. In this situation, the preachers also relied a lot on the general stock of OE religious lexis – on established, frequent and diffused terms – provided they were not in conflict with the new devotional practices, as Helend seems to have become, with polysemous and unmarked lexemes within this category having an even higher chance of survival.