Introduction

Since the early twentieth century, archaeologists have examined how inherited cultural practices such as kinship, wealth, subsistence and access to resources are reflected in the archaeological record (e.g. Kroeber Reference Kroeber1916; Colton Reference Colton1942). While inheritance is essential to evolutionary theory, both biological and cultural (Shennan Reference Shennan2011a; Bonduriansky & Day Reference Bonduriansky and Day2018), some anthropologists and archaeologists are calling for the dismissal of inheritance in cultural evolution altogether. One proposal, for instance, offers a new concept, ‘perdurance’, defined as the “continual bringing forth or production of a world that—in the passage of generations—is ever in formation” (Ingold Reference Ingold2022: S37). This contrasts with evolutionary archaeology, which views items in the archaeological record as proxies for studying the transmission of cultural traits between people in a process of descent with modification (O'Brien & Lyman Reference O'Brien and Lyman2002). On an intergenerational timescale, this is nothing but cultural inheritance, akin to biological inheritance.

Key themes in this debate include agency—how individuals shape and are shaped by social norms, cosmology and status hierarchies—and intentionality. Cultural historian Albert Spaulding (Reference Spaulding, Meggers and Evans1954: 14) characterised culture by “its continuous transmission through the agency of person-to-person contact”. Agency theory is compatible with evolutionary archaeology (e.g. Ribeiro Reference Ribeiro2022), despite a focus in agency theory on how variants are intentionally introduced into cultural evolution. Evolutionary archaeology, by contrast, analyses variation regardless of intent (O'Brien & Holland Reference O'Brien and Holland1992), not only because “evidence of these individual decisions cannot be recovered by archaeologists” (Flannery Reference Flannery1967: 122) but also because short-term intentions, as microevolutionary processes, do not direct the long-term process of macroevolution. Weeding and seed harvesting, for example, are short-term individual intentions, whereas generations of those inherited practices were unintentionally pivotal to the cultural evolution of agriculture (Rindos Reference Rindos1984), “with unexpectedly sustained cultural connections in deep time” (Allaby et al. Reference Allaby, Stevens, Kistler and Fuller2022: 268).

Inheritance and learning

Most archaeologists would agree that intentionality is framed by inherited social practices and knowledge (e.g. Hodder & Cessford Reference Hodder and Cessford2004; Ribeiro Reference Ribeiro2022). In life, daily routines become embedded in social rules, obligations and interactions, to the point of being ‘embodied’ human movements (Roux Reference Roux2007). The creativity of children, for example, usually becomes constrained in adolescence by social norms (Lew-Levy et al. Reference Lew-Levy, Milks, Lavi, Pope and Friesem2020). As Hodder and Cessford described:

As a child grows up within routinized domestic space, it learns that particular practices, movements, ways of holding oneself, deferential gestures, and so on are positively valued while others are not. The child learns social rules in the practices of daily life within the house. In this way daily practices become social practices (Hodder & Cessford Reference Hodder and Cessford2004: 18).

In evolutionary archaeology, this learning is termed cultural inheritance, which creates traditions, which are identifiable as patterned ways of doing things over extended periods of time (O'Brien et al. Reference O'Brien, Lyman, Mesoudi and VanPool2010). Learning is an “extension of biology through culture” (Whiten Reference Whiten2017: 1). In cultural evolutionary theory, culture is information—such as knowledge, beliefs and skills—transmitted between individuals through learning pathways. As cultural inheritance is often cumulative, “beneficial modifications are culturally transmitted and progressively accumulated over time” (Derex Reference Derex2021: 1).

Cultural inheritance and the longue durée

Most of the archaeological record documents the slow evolution of cultural practices through time—the ‘longue durée’ (Braudel 1958). Consistency through time is the result of cultural inheritance. Take, for example, the 700 000-year-long sequence of Acheulean stone tools (1.2–0.5mya) at Olorgesailie, Kenya (Deino et al. Reference Deino, Behrensmeyer, Brooks, Yellen, Sharp and Potts2018). The thousands of handaxes at this site, spread across 29 stratigraphic levels, arguably represent the longest sequence of cultural inheritance in the archaeological record, perhaps with some genetically induced hardwiring in the brain as an assist (Corbey et al. Reference Corbey, Jagich, Vaesen and Collard2016). Does this mean that Acheulean handaxes never changed, even slightly, through time? No; within this millennia-long tradition (Key Reference Key2022), variations in handaxe form and production were subject to the evolutionary processes of isolation, drift and selection. The practice was inherited through a learning balance between imitation (copy how to do it) and emulation (copy the goal and figure out how to do it).

As tools became more complex, imitation became predominant. Neanderthals maintained the Mousterian stone-tool technology for roughly 250 000 years, exhibiting only a few different knapping methods (Lycett & Eren Reference Lycett and Eren2013). Neanderthal diet was similarly conservative for tens of thousands of years—mainly meat (Richards & Trinkhaus Reference Richards and Trinkhaus2009) from hunting strategies focused on local animals (Berlioz et al. Reference Berlioz, Capdepon and Discamps2023). This behavioural tradition is consistent with genetic evidence that Neanderthals lived in small groups of closely related kin, with sustained parental investment in children (Ríos et al. Reference Ríos2019; Skov et al. Reference Skov2022). After modern humans entered western Europe about 45 000 years ago, Neanderthals rapidly learned a new material culture and even interbred with the new arrivals (Hajdinjak et al. Reference Hajdinjak2021).

In Holocene Europe, isotopic and ancient DNA (aDNA) evidence suggests that co-existing groups in certain regions maintained their distinct, inherited forms of subsistence, including hunting–gathering, pastoralism and crop cultivation, potentially for millennia (Bollongino et al. Reference Bollongino2013; Lazaridis et al. Reference Lazaridis2014). Archaeological assemblages such as the Linearbandkeramik—with distinctive longhouses, incised pottery, stone tools, cultivation practices and livestock, division of labour (Masclans et al. Reference Masclans, Hamon, Jeunesse and Bickle2021) and intergenerational wealth transfers (Kohler et al. Reference Kohler2017)—reflect long-term cultural inheritance (e.g. Shennan Reference Shennan2011b). This led to regional variations (e.g. Bickle et al. Reference Bickle2014), and the inherited memories of specific places were such that later Neolithic houses were sometimes constructed on or near houses or burials from preceding centuries (e.g. Quinn Reference Quinn2015; Pyzel Reference Pyzel2019).

Kinship and inheritance

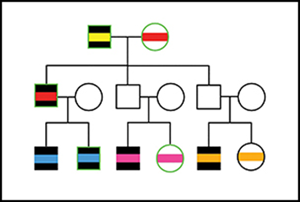

In Europe during and after the Neolithic, the inheritance of subsistence practices, social structures and material cultures followed kinship lines (Figure 1). Such kinship systems, which in central Europe were most often patrilocal and patrilineal, were themselves inherited, according to isotopic, genetic and linguistic evidence (Knipper et al. Reference Knipper2017; Moravec et al. Reference Moravec2018; Mittnik et al. Reference Mittnik2019; Sjögren et al. Reference Sjögren2020; Bentley Reference Bentley2022; Blöcher et al. Reference Blöcher2023). Additional evidence comes from sites such as Gurgy les Noisats, France, where aDNA links dozens of males to one male ancestor (Rivollat et al. Reference Rivollat2023), and Hazleton North, England, where 15 men, but no women, buried over five generations were descended from a single male (Fowler et al. Reference Fowler2022). These interpretations of patriliny or patrilocality in Neolithic Europe have been criticised as reflecting heteronormative male bias (e.g. Bickle & Hoffman 2007; Frieman Reference Frieman2021) or an “obsession with nuclear families” (Ensor Reference Ensor2021: 241), which present “a gendered travel dichotomy [in which] women who travel do so for men” (Frieman et al. Reference Frieman, Teather and Morgan2019: 156).

Figure 1. Representation of at least three generations of a larger paternal lineage, in burials from Haunstetten Postillionstraße in southern Germany, late third to early second millennia BC. Black fill indicates Y-chromosomal haplogroup consistent with one lineage. The colour of the bar in the middle of each symbol represents the mtDNA haplogroup. Individuals with rich grave goods are outlined in green. Additional individuals in richly furnished burials, not shown, were determined to be related to the patrilineage (figure by authors after Mittnik et al. Reference Mittnik2019: fig. 3 and Mittnik et al. Reference Mittnik, Meller, Krause, Haak and Risch2023: fig. 7).

In emphasising the agency for creative expression of kinship (e.g. Bickle & Hofmann Reference Bickle and Hofmann2007; Johnson & Paul Reference Johnson and Paul2016; Brück Reference Brück2021; Ensor Reference Ensor2021), the objections seem to miss what was possible in the past. There is no reason to assume that women migrated for men (Montón-Subías & Hernando Reference Montón-Subías and Hernando2018; Frieman Reference Frieman2021). Women in post-Neolithic Europe were physically strong (Macintosh et al. Reference Macintosh, Pinhasi and Stock2017), and the aDNA and isotopic evidence appears to reflect women as the protagonists in these patrilineal kinship systems (e.g. Bickle Reference Bickle2020; Fowler Reference Fowler2022). The bioarchaeological evidence actually indicates that men were more restricted in their movements than women—especially women with status and wealth.

In late Neolithic and early Bronze Age central and western Europe, mobile women (determined from isotopes) were buried with greater wealth than local women (Mittnik et al. Reference Mittnik2019). At the Bronze Age site of La Almoloya, Spain, for example—where a richly adorned woman was buried together with an unadorned man (Curry Reference Curry2023)—genome-wide data from 67 individuals identified all first-degree relationships among adults as involving at least one adult male, with no first-degree relationships among the 30 adult women analysed (Villalba-Mouco et al. Reference Villalba-Mouco2021). At Hazleton North, maternal sub-lineages are suggested by the descendants of one male being buried in association with each of four respective female partners (Curry Reference Curry2023; Fowler et al. Reference Fowler2022). In Chalcolithic–Early Bronze Age Britain, “the significance of women within patrilineal communities may be indicated by the presence of female inhumations in central positions within mortuary monuments” (Booth et al. Reference Booth, Brück, Brace and Barnes2021). In Bronze Age and Iron Age Europe, women were not only elites and specialists (Bergerbrant Reference Bergerbrant, Berge and Henriksen2019; Blank et al. Reference Blank2021; Jarman Reference Jarman2021) but also highly ranked warriors (Price et al. Reference Price2019; Moen & Walsh Reference Moen and Walsh2021).

If we allow that bioarchaeological patterns reflect inherited kinship systems, a compelling research question follows: why did patrilocality and patriliny arise in Neolithic central Europe specifically? As close as southern Scandinavia, where Bronze Age women were buried in tree coffins with arm rings and belt plates (Bergerbrant Reference Bergerbrant, Berge and Henriksen2019), isotopic analysis suggests the presence of more-varied mobility (and hence kinship?) patterns than in central Europe (Frei et al. Reference Frei2019). Elsewhere in the prehistoric world, bioarchaeological and cultural-phylogenetic methods reveal greater diversity of kinship systems, including matriliny (Jordan et al. Reference Jordan, Gray, Greenhill and Mace2009; Alt et al. Reference Alt2013; Larsen et al. Reference Larsen2015; Kennett et al. Reference Kennett2017; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Moore and Bayman2021; Yaka et al. Reference Yaka2021; Bentley Reference Bentley2022; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Miller, Bayarsaikhan, Johannesson, Miller, Warinner and Jeong2023). Taken together, this suggests that patriliny arose in Neolithic central Europe as a regional anomaly that persisted through its own rules of inheritance. Similarly, in human behavioural ecology, patriliny is explained as a relatively recent departure from the matrifocal origins of human society as cooperative breeders (Hrdy Reference Hrdy2009; Shenk et al. Reference Shenk, Begley, Nolin and Swiatek2019). The proximal causes for patriliny—often as interferences to how relations (‘alloparents’) can help parents raise children—can include wealth inheritance, pastoralism, settlement pattern, intensive cultivation and religion (Sear & Mace Reference Sear and Mace2008; Strassman et al. Reference Strassmann, Kurapati, Hug, Burke, Gillespie, Karafet and Hammer2012; Perry & Daly Reference Perry and Daly2017; Scelza et al. Reference Scelza2020).

Projecting our agency onto the past

To assume prehistoric life was much more variable, or more intentional, than the evidence indicates biases in archaeological interpretation. Contemporary scholars are surrounded by thousands, or millions, of times more material objects, ideas and social contacts than most humans who ever lived (Colwell Reference Colwell2023). In contrast, prehistoric knowledge was transferred from teachers to learners over generations, with increasing teacher–learner investment as technologies became more complex. Ethnohistorical and experimental archaeology indicate that, whereas it took hundreds of hours to master the knapping skills for an Acheulean handaxe (Stout et al. Reference Stout, Hecht, Khreisheh, Bradley and Chaminade2015), it required a decade of apprenticeship to become an expert in Harappan bead-making or ceramic wheel-throwing (Roux Reference Roux2007). It may be hard for modern scholars to conceptualise the inheritance of cultural traditions—such as cultivating crops, herding livestock and barrow-building (Haughton & Løvschal Reference Haughton and Løvschal2023), replastering house walls (Hodder & Cessford Reference Hodder and Cessford2004), telling folk tales (Graça da Silva & Tehrani Reference Graça da Silva and Tehrani2016) or depositing human bodies in bogs (van Beek et al. Reference van Beek, Quik, Bergerbrant, Huisman and Kama2023)—over centuries or millennia.

Periods of slow cultural change were eventually punctuated by cascades of innovation in sociopolitical organisation, specialised-product innovation, exchange networks and food production (Radivojević & Grujić Reference Radivojević and Grujić2018; Frieman & Lewis Reference Frieman and Lewis2021; Bellwood Reference Bellwood2023) and even kinship systems (Moravec et al. Reference Moravec2018). Cascades often reflect feedback in the inheritance of technologies and practices in regional networks, such as gold mining within the Bronze Age Caucasus (Erb-Satullo Reference Erb-Satullo2021). But while innovation cascades may seem to reflect intentional creativity (Soafer Reference Soafer2018), or a game-changing invention spurring complementary inventions (Kolodny et al. Reference Kolodny, Creanza and Feldman2015; Derex Reference Derex2021), they are ultimately driven by the effective size of the population exchanging ideas (Bettencourt & West Reference Bettencourt and West2010; Shennan Reference Shennan2011a; Vaesen & Houkes Reference Vaesen and Houkes2021; Vidiella et al. Reference Vidiella, Carrignon, Bentley, O'Brien and Valverde2022), which is affected by mobility and social networks (Scharl Reference Scharl2016; Soafer Reference Soafer2018; Romano et al. Reference Romano, Lozano and Fernández-López de Pablo2020).

It is difficult not to unintentionally project our expectations for material and social possibility onto other cultures, past or present. A half-century after Evans-Pritchard (Reference Evans-Pritchard1940) complained that he was never able to discuss anything but livestock with the Nuer of Sudan, Hutchinson (Reference Hutchinson1985: 625) wrote “in Nuerland, the first question I was asked upon meeting new faces was always the same: ‘Where you come from, do people marry with cattle or with money?’” But cultural inheritance is never a limitation of the individual mind. As Hutchinson (Reference Hutchinson1992: 296) later added, “because cattle and people were in some sense ‘one’, individuals were able to transcend some of the profoundest human frailties and thereby achieve a greater sense of mastery over their world”. Individuals who understood hundreds of local plants at Ohalo II, in Israel, 23 000 years ago (Snir et al. Reference Snir, Nadel, Groman-Yaroslavski, Melamed, Sternberg, Bar-Yosef and Weiss2015) had much more mastery of this knowledge than someone who Googles those plants today.

In summary, cultural inheritance is consistent with multiple perspectives, from macroscopic, intergenerational evolution of cultures to microscopic intentionality in an individual lifetime. There is no need, however, to project the modern academic imagination onto the past (Chapman & Wylie Reference Chapman and Wylie2016). There is more common ground, and the research questions are more vital, in studying the cultural evolutionary process that is central to our understanding of ancient innovation, social organisation and regional diversity.

Acknowledgements

We thank Catherine Frieman, Emma Bentley and an anonymous reviewer for their excellent comments, which greatly improved the manuscript.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or from commercial and not-for-profit sectors.

Debate responses

Antiquity invited four authors to respond to this debate article; with a final response from the original authors.

On the poverty of academic imagination: a response to Bentley & O'Brien by Tim Ingold. Antiquity 98. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2024.106

The past was diverse and deeply creative: a response to Bentley & O'Brien by Catherine J. Frieman. Antiquity 98. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2024.103

Human intent and cultural lineages: a response to Bentley & O'Brien by Anna Marie Prentiss. Antiquity 98. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2024.102

Cultural inheritance and technological evolution: a response to Bentley & O'Brien by A.M. Pollard. Antiquity 98. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2024.113

Final response from Bentley & O'Brien. On cultural traditions and innovation: finding common ground. Antiquity 98. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2024.123