CLINICIAN'S CAPSULE

What is known about the topic?

Preventable transfers from long-term care facilities to emergency departments (EDs) contribute to ED crowding, a major health systems problem.

What did this study ask?

What interventions are most effective at reducing preventable transfers from long-term care facilities to EDs?

What did this study find?

Interventions using multi-disciplinary care teams, and/or regularly scheduled visits from care providers were the most effective.

Why does this study matter to clinicians?

Local implementation of the most effective interventions types could lessen preventable transfers, and thus reduce ED crowding.

INTRODUCTION

Emergency department (ED) crowding is an international health system issue that is worsening.Reference Schull, Slaughter and Redelmeier1 Crowding manifests as prolonged patient wait times and ED lengths of stay, and increased patient mortality and morbidity.Reference Derlet and Richards2 One major contributor is preventable transfers from long-term care facilities. The term long-term care facility encapsulates facilities otherwise referred to as nursing homes, long-term care homes, or residential care facilities.

Typically, long-term care facility patients are transferred to EDs when they suffer complications or medical emergencies that exceeds the facility's care capacity.Reference Ackermann, Kemle, Vogel and Griffin3 In Canada, there were over 60,000 long-term care facility patient transfers to the ED in 2014. However, nearly a quarter of them were due to “potentially preventable conditions” as defined by the Canadian Institute of Health Information, with infection, and fall-related injuries being the most common reported causes.4 These preventable transfers, or transfers that could have been avoided by implementing specific interventions within the long-term care facility, may compromise quality patient care, and increase ED crowding and healthcare costs.Reference Gruneir5,Reference Gruneir, Bronskill and Newman6 A significant portion of these patients are admitted, placing further strain on the patient and their family, and increasing the patient's risk of hospital-acquired complications.Reference Ouslander, Lamb and Perloe7 The strain on EDs from these preventable transfers will only increase as our population continues to age with more complex health care needs.Reference Kawano, Nishiyama, Anan and Tujimura8 Reducing ED overcrowding by preventing these transfers may also alleviate “Hallway Medicine,” identified as one of the most significant health care challenges currently facing Canadians.

Initiatives aimed at reducing these preventable transfers have been shown to improve patient care and ED crowding.Reference Axon and Williams9,Reference Epstein, Huckins and Liu10 There have been many interventions and care pathways to reduce transfers, but these strategies have considerable variation in design and efficacy. Some of these interventions include fall-prevention programs, improving patients transitions into the long-term care facility, and multifaced quality improvement programs. This study's objective is to review, categorize, and evaluate interventions to reduce preventable long-term care facility transfers to EDs.

METHODS

A scoping review was used to synthesize existing studies. While a systematic review methodology was considered, it did not sufficiently address the range of interventions and the heterogeneity in study design and outcomes. The scoping review provided a comprehensive description of the existing evidence and facilitated more focused areas of research.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they were an original research article describing interventions to reduce preventable transfers from long-term care facilities to EDs. Studies needed to have a comparison group and report key outcomes, such as the number of ED transfers. Exclusion criteria were studies published only as abstracts, non-English studies, non-comparative descriptive studies, and home-care- or rehabilitation care-focused studies.

Search strategy

Searches were carried out in Medline (by means of Ovid, 1946 to March 22, 2019), EMBASE (by means of Ovid 1974 to March 22, 2019), and CINAHL (by means of EBSCO, 1982 to March 22, 2019), without the use of filters. The search was designed based on three concepts: the setting (ED and long-term care facilities), the outcomes (ED transfers), and the study type.Reference Rogers, Shankar and Jerris11 The search strategies included both free text terms and subject headings where available. This study adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-Scr) guidelines.Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin12

Screening and data extraction

Two reviewers (K.G. and D.L.) independently screened the titles and abstracts for all studies. Disagreements were resolved by consensus, or if needed, by a third independent reviewer. Inter-rater reliability was assessed with the Cohen K statistic. All remaining studies underwent full text review to confirm they met inclusion criteria. Data from the remaining studies were extracted using a prespecified data extraction sheet, which included the study title, authors, date of publication, design, primary outcome measures, and the results.

Quality assessment

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) quality assessment tools were used to assess the included studies.13 All studies were assessed by two independent reviewers. Disagreements were resolved by consensus, or if needed, by a third independent reviewer.

Data analysis

A tabular summary of all included papers was completed, detailing the study title, authors, date of publication, design, primary outcomes. In both the table and narrative synthesis, the studies were summarized into five themes based on the characteristics of the intervention: Telemedicine, Outreach Teams, Interdisciplinary Care, Integrated Approaches, and Other.

RESULTS

Literature search

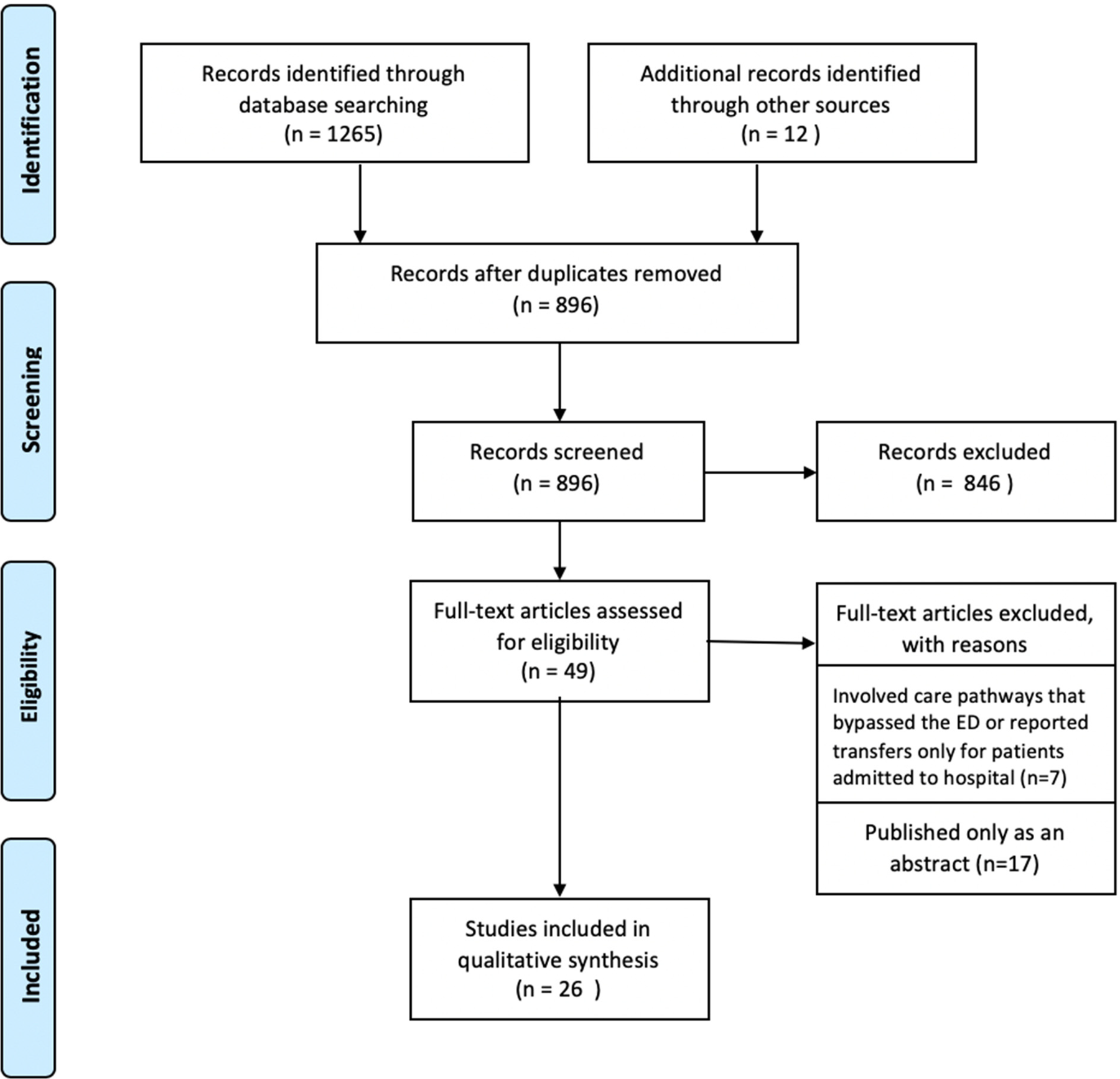

Of the 884 studies returned from search, 39 met inclusion criteria after screening the titles and abstracts. The 12 discrepancies in decisions between the two independent reviewers were resolved by consensus (Cohen's k = 0.68). Twelve additional studies were returned from reference chaining during the full text review.

On full-text review, 23 studies were excluded (Figure 1). Seven studies were excluded because they described alternate care pathways that bypassed the ED entirely, or reported transfers only for patients admitted to hospital. Seventeen studies were excluded because they were only published as abstracts.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram depicting study selection process.

Description of studies

The 26 studies included were divided into five themes based on the characteristics of the interventions: Telemedicine, Outreach Teams, Interdisciplinary Care, Integrated Approaches, and Other. Telemedicine included studies that used telephone or virtual conferencing technologies to connect remote providers to long-term care facilities. Outreach Teams included studies where provider groups operating out of a central hub, travelled to long-term care facilities for patient assessment as-needed, or at regular intervals. Interdisciplinary Care included interventions where multidisciplinary care teams (nurses, primary care physicians, geriatricians, physiotherapists) were formed within the long-term care facilities. Integrated Approaches incorporated multiple interventions aimed at reducing ED transfers. Studies that did not fit into the above four themes were categorized as Other.

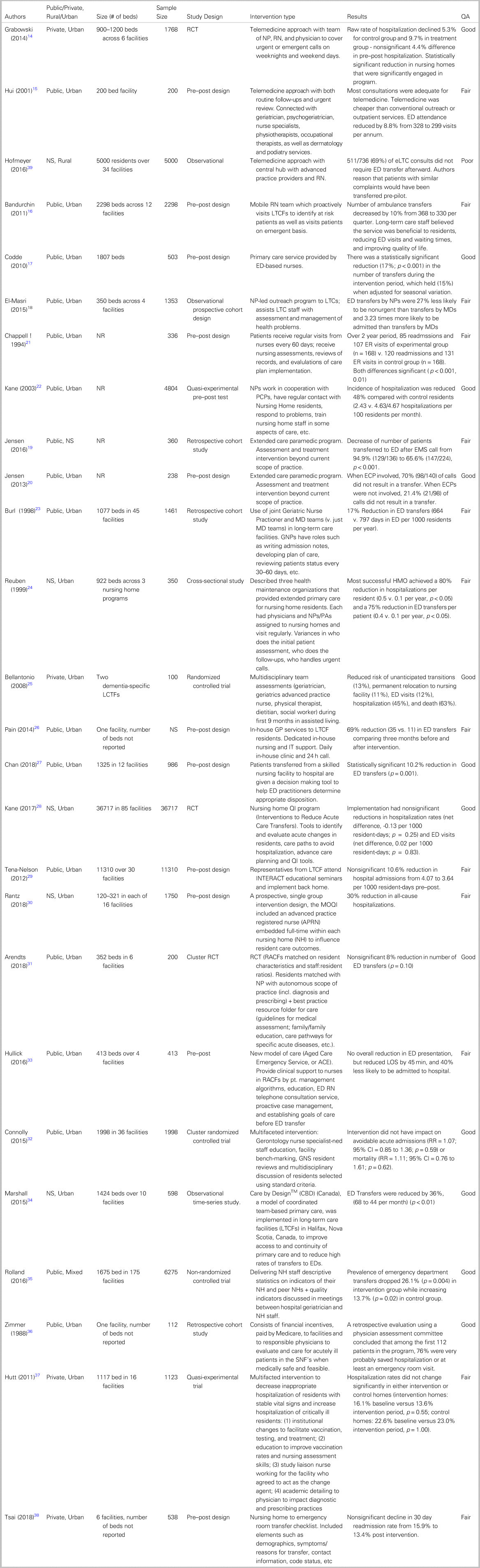

Eighteen of the 26 studies occurred in public long-term care facilities in urban settings. One study was conducted in a public rural long-term care facility, and one study was conducted in public long-term care facilities across a mixture of urban and rural environments. Six studies were conducted in private, urban long-term care facilities (Table 1).

Table 1. Details of the study title, authors, date of publication, long-term care facility location and funding model, study design, primary outcome measures, and results for all 26 included studies, categorized by intervention type.

ED, emergency department; GP, general practitioner; NH, nursing home; QA, quality assessment; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RN, registered nurse; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

Telemedicine

Three studies introduced telemedicine and connected long-term care facility patients and staff to off-site health care providers. Results ranged from a non-significant decrease in transfers of 4.4% to a significant 8.8% reduction of in transfers.Reference Grabowski and O'Malley14,Reference Hui, Woo, Hjelm, Zhang and Tsui15 Hofmeyer et al. did not examine changes in the rate of ED transfers, but reported that 511/736 (69%) telehealth consults over one year did not result in a transfer, while they could have otherwise.

Outreach teams

Three studies evaluated interventions by Outreach Teams. Bandurchin et al. studied a mobile nurse team that identified at-risk patients and attended emergency consultations, which reduced ED transfers by 10%.Reference Bandurchin, McNally and Ferguson-Pare16 Codde et al. described a service in which long-term care facility staff could request in-house services by an emergency nurse with a supervising general practitioner. This team reduced ED transfers by 17%.Reference Codde, Arendts and Frankel17 El-Masri et al. examined a nurse practitioner-led outreach team who provided direct care in long-term care facilities.Reference El-Masri, Omar and Groh18 Although total ED transfer reduction was not measured, the authors noted there was no change of ED transfers between teams led by nurse practitioner versus physicians.

Two studies by Jensen et al. looked at extended care paramedic programs where paramedics managed long-term care patients on-site.Reference Jensen, Marshall, Carter, Boudreau, Burge and Travers19,Reference Jensen, Travers and Bardua20 The studies reported a 31% and 62% reduction in ED transfer rate. Chappell and Murrell found that nurse practitioner visits to long-term care facilities every 60 days were associated with 8% decrease in ED transfers when compared with a control group.Reference Chappell and Murrell21 Kane et al. found that nurse practitioner visits reduced ED transfers by 47.6% compared with the controls.Reference Kane, Keckhafer, Flood, Bershadsky and Siadaty22

Interdisciplinary care

Five studies examined Interdisciplinary Care health care teams. These teams differed from Outreach Care teams because these staff were employed within a single long-term care facility, or network of long-term care facilities. One team included a geriatric nurse practitioner and physician who assessed patients upon admission to the long-term care facility, took call, and made joint rounds, resulting in a 17% reduction in ED transfers.Reference Burl, Bonner, Rao and Khan23

Reuben et al. described how three different health maintenance organizations delivered primary care to long-term care facilities within their network.Reference Reuben, Schnelle and Buchanan24 The most efficacious program was full-time team composed of a physician and mid-level provider, such as a physician assistant or nurse practitioner. The mid-level providers could order diagnostic tests, consultations, and write orders and prescriptions. The team provided call. This intervention reduced ED transfers by 75% compared with the control long-term care facilities.

Bellantonio et al. implemented a multidisciplinary team of geriatricians, geriatric advanced practice nurses, physical therapists, dieticians, and social workers across several long-term care facilities.Reference Bellantonio, Kenny and Fortinsky25 This intervention achieved a non-significant reduction in ED transfers of 12% (p = 0.80). Pain et al. found that a weekly in-house GP clinic with nursing support was associated with a 70% decrease in ED transfers.Reference Pain, Stainkey and Chapman26 Chan et al. studied the effect of a care team consisting of geriatricians and nurses, and reported a 10.2% decrease in ED transfers.Reference Chan, Liu and Irwanto27

Integrated approaches

Eight studies involved Integrated Approaches. Three studies used the INTERACT (Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers) program, a quality improvement program consisting of a set of planning and communication tools to detect acute changes in long-term care facility residents. Two studies found no significant reductions in hospitalization rates, readmission rates, and ED transfers.Reference Kane, Huckfeldt and Tappen28,Reference Tena-Nelson, Santos and Herndon29 Conversely, Rantz et al. used INTERACT and performance feedback with in-home advanced care nurses, which reduced hospital transfers by 30%.Reference Rantz, Popejoy and Vogelsmeier30

Three studies used a combination of multidisciplinary care rounds, patient management algorithms, and telephone consultations but did not report significant reductions in ED transfer rate.Reference Arendts, Deans and O'Brien31–Reference Hullick, Conway and Higgins33 Marshall et al. took a multi-modal approach titled “Care by Design,” incorporating weekly on-site visits, standing orders and protocols, interdisciplinary care teams, and access to extended care paramedic programs in ten long-term care facilities.Reference Marshall, Clarke, Peddle and Jensen34 This program reduced ED transfers by 36%.

Other

Rolland et al. studied a quality improvement program consisting of feedback and audits on predetermined quality indicators and resident health status. Individual long-term care facilities were then able to independently develop interventions to lower transfers. This led to an average ED transfer reduction of 26.1%.Reference Rolland, Mathieu and Piau35

Zimmer et al. created financial Medicare incentives for physicians and long-term care facilities to keep patients within the facility, reducing hospital transfers 75%.Reference Zimmer, Eggert, Treat and Brodows36

Hutt et al. used a multifaceted intervention consisting of long-term care facility staff education, academic detailing, and on-site change agents to decrease transfers among stable patients with long-term care facility -acquired pneumonia. This did not change rates of hospital transfer.Reference Hutt, Ruscin and Linnebur37 Tsai and Tsai studied the use of a transfer document to bridge communication gaps during transitions from long-term care facility to ED and vice versa. The study observed a nonsignificant 1.6% reduction in 30-day hospital admission rate.Reference Tsai and Tsai38

Quality assessment

Of the 26 studies, 11 were rated good, 14 were rated fair, and 1 was rated poor using the NHLBI quality assessment tools. There were six total disagreements between reviewers (Cohen's k = 0.54), all of which were resolved by consensus.

DISCUSSION

Interventions in long-term care facilities in a variety of health care settings have resulted in significant reductions in ED transfers. Specifically, leveraging interdisciplinary teams to provide enhanced primary care seems promising. Second, the implementation strategy for any intervention has been shown to be crucial for success. These findings are particularly important now as limited access to professional expertise and poor care coordination between long-term care facilities and the broader healthcare system have contributed to disproportionate mortality and morbidity from COVID-19 among long-term care facility patients in several jurisdictions.

Only three studies evaluated telemedicine interventions, with mixed results. Hofmeyer et al. (n = 5,000, observational) found that 69% of telemedicine consults could be managed without an ED transfer, but further study is needed to determine if telemedicine interventions are an effective means of reducing preventable transfers from long-term care facilities to EDs.Reference Hofmeyer, Leider, Satorius, Tanenbaum, Basel and Knudson39

While Kane et al. and Jensen et al. reported significant reductions using Outreach team interventions, overall results were mixed across all provider types, suggesting that the design and implementation of the interventions are critical to the impact achieved.

Each of the five interventions involving the use of interdisciplinary teams reduced preventable ED transfers. Reuben et al. and Pain et al. reported the studies with the largest reductions. These interventions were the most effective of all included in this review, and both included regular physician assessments. While it is possible that physicians were best equipped to judge the necessity of a transfer or manage sick patients within the long-term care facility, frequent visits would have enabled these physicians to review these patients’ status on an ongoing basis. This would reduce the overall incidence of events that would warrant transfer. In instances when physicians were consulted on an as needed basis, the reduction in ED transfer rates was more modest.

Studies using integrated approaches had mixed results. Of the three studies that involved the INTERACT program, only the study by Rantz et al. was effective (n = 1750, pre–post design). One of the primary differences between it and the other two INTERACT studies was the presence of dedicated coaches to facilitate the implementation of the program, suggesting that superior program implementation contributed to greater success. Similarly, Kane et al. completed an randomized controlled trial (RCT) with multiple long-term care facilities (n = 36,717, RCT), and that study sites with the greatest transfer reductions reported the highest uptake of the program's tools.Reference Kane, Huckfeldt and Tappen28

Three studies did not fit in any of the previous categories. The positive results of the audit and feedback system by Rolland et al. (n = 6,275; nonrandomized controlled trial), and the financial incentives system by Zimmer et al. (n = 112; retrospective cohort) suggest that there is merit in incentivizing staff to create their own interventions to combat unnecessary transfers.

Twenty-five of the 26 included studies were rated either “Fair” or “Good” in the quality assessment. The one “Poor” rated study suffered from a small sample size and a sampling design where the triage nurse selected patients for the telemedical intervention as they saw fit, which introduced additional potential bias.Reference Hofmeyer, Leider, Satorius, Tanenbaum, Basel and Knudson39 Excluding this study would reduce the number of telemedical interventions from three to two, however, it would not impact the substance of our findings within that intervention grouping, or for the review as a whole.

Limitations

This scoping review has several limitations. First, our searches were limited to studies published in English, which could lead to geographic and health system biases. Second, there was considerable heterogeneity in the study designs, reported outcomes, and results, and no discussion of cost-effectiveness. Furthermore, ED transfer rate was the only consistently reported outcome, limiting understanding of any additional costs or benefits of the interventions. It also remains unclear whether strategies with multiple elements, such as the INTERACT program, may be more effective than single interventions, a finding that has been demonstrated in previous research on healthcare transitions.Reference Kripalani, Theobald, Anctil and Vasilevskis40 Finally, four studies reported reductions in hospital transfers as opposed to ED transfers.Reference Grabowski and O'Malley14,Reference Tena-Nelson, Santos and Herndon29,Reference Rantz, Popejoy and Vogelsmeier30,Reference Connolly, Boyd and Broad32 We used this as a proxy measure for ED transfers, although it is possible that some of these patients could have bypassed the ED.

CONCLUSION

Reducing preventable transfers from long-term care facilities to EDs improves patient care and has the potential to reduce ED crowding and health care costs. There are several intervention types that reduce preventable transfers from long-term care facilities to EDs, with interdisciplinary team interventions being particularly effective. Additional studies emphasizing a mixed methods design, economic analyses, and care coordination between long-term care facilities and local EDs would further inform health care policy, and administrative decision-making.

Competing interests

None declared.