1. Introduction

Reflection on religiosity as a subjective presence of religion in the lives of individuals and societies, and its transformations, is an important part of an attempt to interpret changes taking place in the world since the beginning of the sociology of religion itself at the turn of the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries. In the 1940s, Gabriel Le Bras noted the waning of what he called the “religious vitality” of French society in metropolitan centers and industrialized regions (Le Bras, Reference Le Bras1944). In the 1960s and later, a view crystallized that linked the decline in religiosity to secularization (Berger, Reference Berger1967; Dobbelaere, Reference Dobbelaere2004). This interpretative trend, which has for several decades applied especially to Western Europe, has been challenged by other competing concepts, including the privatization of religion (Luckmann, Reference Luckmann1967), religion as memory (Hervieu-Léger, Reference Hervieu-Léger2000), lived religion (Pace, Reference Pace and Ammerman2007; McGuire, Reference McGuire2008), vicarious religion (Davie, Reference Davie and Ammerman2007), and diffused religion (Cipriani, Reference Cipriani2017). What these concepts share is the idea that manifestations of religiosity should not be equated with its forms, and that individuals can attach religious meanings to personal experiences and actions that have no connection to the official teachings of any established church. In other words, in this approach modern societies are seen as affected by a transformation of religion that takes diverse forms, rather than undergoing secularization as such.

However, in Poland, but also in Croatia, Malta, Greece, Romania, and outside Europe in Mexico, the traditional, institutionalized form of religiosity is strong, indicators of religiosity (belief, practice, knowledge, experience, and consequences) (Stark and Glock, Reference Stark and Glock1974) are at a generally high level, and a single, dominant church is a significant actor in social life (Borowik, Reference Borowik2010). How does the clash between modernity and religion play out in such countries? What is the response of these societies to the challenges that modernity poses to traditional forms of religiosity, and what are the measures of the importance of religion? A concept that may prove useful in this context is religious pluralism, which is most frequently understood as presence of different religious traditions in a given area at the same time. This kind of pluralism is highlighted as a feature of the European religious landscape, primarily in the context of successive waves of migration, which result in a presence of numerous representatives of a previously unobserved religious tradition, as is often the case with Islam (Michel and Pace, Reference Michel and Pace2011; Giordan and Pace, Reference Giordan and Pace2014; Furseth, Reference Furseth2018).Footnote 1 However, such an understanding of pluralism is inadequate in the case of contemporary Poland, which is almost homogeneous in terms of its religious structure. Therefore, we shall adopt a different meaning of the term and understand pluralism as empirical diversity within distinct religious traditions (Beckford, Reference Beckford, Michel and Pace2011).

In this article we look at differentiation of religiosity as a manifestation of intra-religious pluralism and a feature of functional differentiation of a religious sub-system (Luhmann, Reference Luhmann2013; Beyer, Reference Beyer2020), as believers and the way in which they practice their religion are part of it. By using the term “differentiation of religiosity” we intend to make a linkage/connection between religious pluralism and subjective religiosity, expressed in answers to the questions indicating beliefs, practices, Church authority, and so on, i.e., parameters of religiosity, and use latent class analysis (LCA) as a way of discovering how that differentiation empirically appears. In other words, differentiation of religiosity means differentiation of religious beliefs and practices that are meaningful to individuals yet shared by many (Pearce et al., Reference Pearce, Michael Foster and Hardie2013).

Differentiation of religiosity therefore means the occurrence of various types and profiles of religiosity. However, neither their number nor the configurations of practices and beliefs that constitute them can be deduced from theoretical premises. We argue that empirical analyses of religious differentiation conducted on the basis of a priori expectations are problematic. This is because they are based on the premises that people are characterized by a coherent (i.e., corresponding to theoretical premises) system of convictions, practices, and beliefs. However, the results of empirical research do not support such assumptions. For example, Smith and Denton (Reference Smith and Denton2005) designated four ideal types of religiosity among adolescents: the Devoted, the Regulars, the Sporadic, and the Disengaged. Unfortunately, their classification scheme covers only 63% of the young people in the study. More than a third of the cases could not be classified into any of the assumed types of religiosity. The reality turned out to be too complex, and the consistency of behavior and religious beliefs overestimated.

As Halstead et al. (Reference Halstead, Heron and Joinson2022, 3) note: “This fails to account for the many potentially contrary beliefs, feelings or behaviors that constitute religiosity. For example, it is conceivable that a deeply religious person may not attend a place of worship or believe that God personally intervenes to help them in times of trouble.” In this article, we therefore expect that the empirical data will demonstrate internal differentiation of religiosity, i.e., pointing to their various profiles of Polish Catholics, but we do not assume either their number or the specific configurations of beliefs and the behaviors that constitute them.

Taking into account the generally high level of and stable identification with Catholicism in Poland, the question arises as to whether, and if so how, the religiosity of Catholics is actually differentiated. How many treat it as a kind of cultural, historically determined tradition, and how many profess that their faith is integrated into their experience of the world, giving meaning to reality and providing legitimacy to their decisions, in accordance with Berger's idea that as a result of pluralization, pressure increases toward making more conscious choices from among many possible options (Berger, Reference Berger2007, Reference Berger2014).

The authors approached the issue of the consequences of Catholic religiosity, if any, from the perspective of attitudes toward biopolitical topics. Literally, biopolitics (Foucault, Reference Foucault2010) denotes politics that has to do with life (Greek: bíos) (Lemke, Reference Lemke2010) and refers to the human species, i.e., the processes of birth, aging, disease, and death (Turina, Reference Turina2013). Since the central point of biopolitical considerations is human life, it should come as no surprise that biopolitical themes cover a wide range of questions related to reproduction, fertility, longevity of life, and mortality. Three biopolitical topics were addressed in the study presented, i.e., abortion, in vitro fertilization (IVF), and homosexuality. These topics are of vital interest to the Roman Catholic Church (RCC), whose teachings dictate moral principles related to the body and reproduction with the aim of influencing social views and political decisions (Turner, Reference Turner1996, Reference Turner2013; Weiberg-Salzmann and Willems, Reference Weiberg-Salzmann and Willems2020).

Research shows the presence of a relationship between religiosity and attitudes toward abortion, IVF, and homosexuality. Numerous studies have confirmed that people who belong to a religious denomination, regardless of the religious tradition or the region of the world, compared to those who do not, are more likely to hold restrictive (conservative) views on all three topics: abortion (Wall et al., Reference Wall1999; Jozkowski et al., Reference Jozkowski, Crawford and Hunt2018), abortion and IVF (Silber Mohamed, Reference Silber Mohamed2018), and homosexuality along with the right of homosexual couples to civil unions (Olson et al., Reference Olson, Cadge and Harrison2006; Scheitle and Adamczyk, Reference Scheitle and Adamczyk2009; Hayes and McKinnon, Reference Hayes and McKinnon2018; Adamczyk et al., Reference Adamczyk, Kim and Dillon2020). In the studies comparing the attitudes of different religions, Catholics, as the group of particular interest to us, are more likely to advocate more conservative views, although not as restrictive as Muslims or Evangelicals (Crockett and Voas, Reference Crockett and Voas2004; Adamczyk and Felson, Reference Adamczyk and Felson2008; Adamczyk, Reference Adamczyk2009; Sullins, Reference Sullins2010).

At the same time, research suggests that the intensity of certain parameters of religiosity may have more power in differentiating opinions than affiliation alone. For example, the strength of an association between religion and attitudes toward homosexuality increases when religious practices are considered. The views of people who attend religious services less than once a month are similar to those of those who never participate in religious services (Crockett and Voas, Reference Crockett and Voas2004). Another dimension of religiosity, namely the importance that people attach to religion in their lives, has a similar effect. The differences between those who believe that religion is “very important” in their lives and those who choose the option that religion is “not important at all” are significant. In the former group 30% more respondents believe that abortion is “morally wrong,” and when it comes to IVF the figure is 10% higher (Silber Mohamed, Reference Silber Mohamed2018). When the belief in God and the frequency of religious practices are considered together, the relationship is similar: people who declared themselves to be practicing believers more often expressed conservative views on abortion and homosexual relationships (Hayes and McKinnon, Reference Hayes and McKinnon2018).

Additionally, research confirms the importance of the religious structure prevailing in a country, in particular the existence of religious pluralism, interpreted as a coexistence of several denominations versus the dominance of one religious faith.

In the case of a heterogeneous structure of religiously (and ideologically) pluralistic societies, the position of different churches and their ability to expose their views on biopolitical issues is different than when the position of one church is dominant, and in all truth privileged, as is the case in Poland (Weiberg-Salzmann and Willems, Reference Weiberg-Salzmann and Willems2020). With no competing views from other religious institutions, the position of the dominant church becomes widespread.

The RCC has consistently advocated a complete ban on abortion and IVF, and in the case of homosexuality abstinence from engaging in sexual practices as a condition for remaining in the Catholic community (Kulczycki, Reference Kulczycki1995; Dillon, Reference Dillon1996; Hitchcock, Reference Hitchcock2016; Kozlowska et al., Reference Kozlowska, Béland and Lecours2016; Ziebertz and Zaccaria, Reference Ziebertz and Zaccaria2019b). Comparative studies show that in the case of Poland, the voice of the RCC is particularly uncompromising, and the pressure on politicians to pass certain laws is more categorical and direct than is the case in other countries dominated by Catholicism (Kulczycki, Reference Kulczycki1995; Dillon, Reference Dillon1996; Kozlowska et al., Reference Kozlowska, Béland and Lecours2016). This may result from the fact that, as indicated by Minkenberg's (Reference Minkenberg2002) analysis of abortion laws in 33 Western European countries, the likelihood of the most restrictive solutions being adopted is supported by a combination of: (1) high religiosity in certain societies, in conjunction with (2) amicable regulation of relations between the state and the Church, and (3) the presence of religiously rooted elites. Poland meets all three conditions. In a similar vein, Simon Fink, who analyzed the laws governing embryo research, argues that the denominational social structure is the most powerful explanatory variable; he has also emphasized the consistent and influential impact of the RCC on such laws (Fink, Reference Fink2008).

In Poland, the situation structurally defined in this way makes the widely propagated views of the Church well known to the Polish people in general, and Catholics in particular. It seems therefore interesting to explore the question of to what extent Polish Catholics, who constitute almost 90% of the general population, share the position of their Church? We assume that pluralism within the Catholic community is expressed in: (a) differences in the degree of religious orthodoxy, understood as meeting the expectations of the Church in terms of sharing the faith, following religious practices, and being subject to the authority of the institution and its teachings; (b) diversity in the attitudes of Catholics (Kulczycki, Reference Kulczycki1995; Dillon, Reference Dillon1996; Kozlowska et al., Reference Kozlowska, Béland and Lecours2016), and (c) the diversity of Catholic attitudes toward abortion, IVF, and homosexuality. We also assume the existence of a significant relationship between religiosity and attitudes toward abortion, IVF, and homosexuality.

In our analyses we refer to the results of surveys carried out on a large, representative sample of Polish residents, which allows us to overcome one of the main limitations of the existing body of research in relation to the study of the relationship between religiosity and biopolitical topics, namely its unrepresentativeness. A significant part of research to date has been based on the materials obtained on the basis of purposive sampling that included specific social groups (most often young people from different countries) (Wall et al., Reference Wall1999; Roggemans et al., Reference Roggemans, Spruyt, Van Droogenbroeck and Keppens2015; Ziebertz and Zaccaria, Reference Ziebertz and Zaccaria2019a). This does not allow for a generalization of conclusions to the entire population (of a given country or religion).

A relatively narrow understanding of religiosity also proves to be a key limitation, as evidenced by the meta-analysis conducted by Adamczyk et al. (Reference Adamczyk, Kim and Dillon2020) on the attitudes of Americans toward abortion and their determinants. The authors point out that in research to date, two elements related to religiosity have most frequently been used (55% of publications): religious affiliation and religious practices. In as many as 45% of the studies a single variable was used, such as either religious affiliation or religious practices. Only three publications examined more variables, such as frequency of prayer, experience of the presence of God in one's life, or the teachings of Jesus (Adamczyk et al., Reference Adamczyk, Kim and Dillon2020, 8). The review of publications to date suggests that more research is required to acknowledge the fact that religion is multidimensional, and that the list of investigated variables should be expanded. In the tradition of research on religiosity, many such assumptions have been previously made (Glock and Stark, Reference Glock and Stark1965; Klemmack and Cardwell, Reference Klemmack and Cardwell1973; Mueller, Reference Mueller1980); otherwise, religiosity as a multidimensional human experience, taking place on many levels, can be neither understood within the framework of one-dimensional interpretations nor reduced to a single variable (Kucukcan, Reference Kucukcan2005).

Given the multidimensionality of religiosity, researchers are forced to create multi-item questionnaires that consider different aspects of religiosity (see: Hill and Hood, Reference Hill and Hood1999, 269–339; Chapter 8—Multidimensional Scales of Religiousness). An alternative is to develop a typology of religious profiles that can be constructed: (a) a priori (conceptually derived), i.e., based on the assumptions of predetermined groupings (subtypes of religiosity), or (b) data-driven, i.e., based on an inductive statistical method (Pearce et al., Reference Pearce, Hayward and Pearlman2017)—for example, person-centered methods, like LCA (Collins and Lanza, Reference Collins and Lanza2010).

LCA is a statistical method for dividing respondents into groups sharing certain characteristics by empirically identifying relatively homogeneous subpopulations from the patterns of observed variables, known as “indicators.” These homogeneous groups are referred to as “latent classes” because they are an unobservable variable which is conceptually defined but can be measured indirectly through the manifest response pattern. In brief, in LCA individuals with a similar response to survey items are placed into the same class. In the analysis presented here, we have used LCA to capture the internal variations in Catholic religiosity, and their orientation toward IVF, abortion, and homosexuality.

2. Methods

2.1. The statistical analysis

The purpose of LCA is to find the most parsimonious model for interpretation, i.e., to find a model in which the number of classes is sufficient for explaining the associations between the manifest variables. In LCA the number of latent classes is unknown and cannot be estimated directly but in a series of nested models with an accumulative number of classes (up to seven classes in our research).

The optimal model was determined with reference to two likelihood ratio tests: the Vuong–Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio test (VLMR LRT) and the Lo–Mendell–Rubin-adjusted likelihood ratio test (LMR-A). Both tests compare whether a k class solution fits better than a k − 1 class solution and provide a p-value that can be used to determine whether there is a statistically significant improvement in the fit for the inclusion of one more class. In other words, a p <0.05 suggests that the specified model provides a better fit to the data relative to the model with one fewer class.

We also used four information criterion indices, i.e., the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), the sample-size-adjusted BIC (SSA-BIC), the Akaike information criterion (AIC), and the finite sample-corrected AIC (AICc). For all four coefficients, smaller values indicate a better model fit. Furthermore, the entropy values were calculated as an overall measure of classification uncertainty (Kaplan and Keller, Reference Kaplan and Keller2011). Entropy can take values from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating perfect classification. A higher coefficient value means a better fit of the model. High classification certainty indicates that an individual's probability of membership is high for one class and low for others. Low classification certainty suggests class overlap and the possibility that individuals are likely members of multiple classes. Although there are no clear cut-off points (Wang and Wang, Reference Wang and Wang2012), a value of 0.80 is considered high, 0.60 is considered medium, and 0.40 is considered low entropy (Clark, Reference Clark2010). An LCA was conducted using the Mplus 8.3 statistical package (Muthén and Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2017).

After the optimal number of classes was determined, participants were assigned to the one in which they had the highest probability of membership, and cumulative ordinal regression (Bürkner and Vuorre, Reference Bürkner and Vuorre2019) was used to determine which of the identified variables (social, demographic, political, etc.) predict class membership, adjusted for all other variables in the model(s). As a predictive analysis, ordinal regression describes data and explains the relationship between one dependent variable (polytomous ordinal with three or more categories) and two or more independent (binary or continuous-level) variables. For regression modeling we use the brms package (Bürkner, Reference Bürkner2017) in R (R Core Team, 2013).

2.2. Participants and procedures

The study used a nationally representative sample of Polish adults (aged ≥18). The sample consisted of 1,066 participants. Recruitment, face-to-face interviews, and data entry were conducted by the Public Opinion Research Centre in Warsaw. Data were collected using the computer-assisted web interviewing technique between February 26 and 28, 2020.

In total, 84.4% of our respondents declared affiliation to a religious denomination (13.8% declared being non-denominational, 1.1% were not sure, and 0.7% refused to answer). Among the people who declared affiliation to a religion, RCC members clearly dominated (97.1%), but a few people declared that they belonged to the Orthodox Church (0.8%), Jehovah's Witnesses (0.4%), the Greek Catholic Church (0.2%), and the Protestant Church (0.2%).Footnote 2 The socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents (in total, Catholics only, and non-denominational or affiliated to a denomination other than Roman Catholic) are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Religiosity

The authors operationalized the concept of religiosity by combining a number of variables (see Figure 1) measuring different aspects of religiosity, such as: (1) self-declaration of faith; (2) belief in the importance of religion and faith in daily life; (3) faith in salvation; (4) the role of God in the lives of the respondents; (5) religious practices; (6) beliefs about the authority of religion and the Church in making life decisions; and (7) the functions performed by the Church as perceived by respondents.

Figure 1. Measures of religious orientation.

The analysis of the distributions of seven religious variables indicates that almost 90% of Catholics identified themselves as believers or deeply religious. Fewer (approximately two-thirds) declare that they are guided in their lives by religion and faith and believe that God influences human life, and half admit that they are guided in their lives by the authority and teaching of the RCC and have positive opinions about it. At the same time, more than half believe, contrary to the RCC teaching, that anyone can be saved, and fewer than half participate in religious practices at least once a week. Thus, the religiosity of Catholics is quite strongly differentiated, depending on the parameter examined.

2.3.2. Biopolitical themes

Six questions were used to determine the respondents' orientation toward the three biopolitical themes (see Figure 2). Three of them measured the level of punitiveness toward the biopolitical issues examined; the other three aimed to identify to what extent the respondents are inclined to consider these phenomena (i.e., abortion, homosexuality, and IVF) in terms of axiologically positive, neutral, or negative categories. In addition, in the case of negative categories answers of a religious or non-religious nature were distinguished.

Figure 2. Measures of orientation toward biopolitical themes.

For this study, the number of original response categories to three axiological questions was reduced to fewer response categories, i.e., five general categories: (1) negative religious justifications, (2) negative non-religious justification, (3) neutral justifications, (4) positive justifications, and (5) other.Footnote 3 Collapsing the categories reduces the number of possible response patterns and the required sample size, increasing the chances of correct model estimation, i.e., yielding higher convergence rates (Eid et al., Reference Eid, Langeheine and Diener2003). Reducing the number of categories also makes it easier to interpret the results.

The respondents' orientation toward the three topics analyzed was found to be diverse. Most commonly, they approved of IVF, even though their approval was often conditional (as long as IVF was used by married people). Although the level of acceptance for abortion and homosexuality was found to be lower, only every fifth respondent rejected them unconditionally. The diverse approach to biopolitical issues was also confirmed by an analysis of the terms used to respond to them. While in the case of IVF neutral or positive concepts were most often used when it came to abortion and homosexuality these were neutral or negative. At the same time, in the case of each of the three topics, only a small percentage of negative terms referred to the language containing religious connotations. Not only religiosity but also the orientation toward biopolitical topics of a significant number of the Catholics in our sample deviated from the RCC teaching.

3. Results

3.1. Three classes of religiosity among Polish Catholics

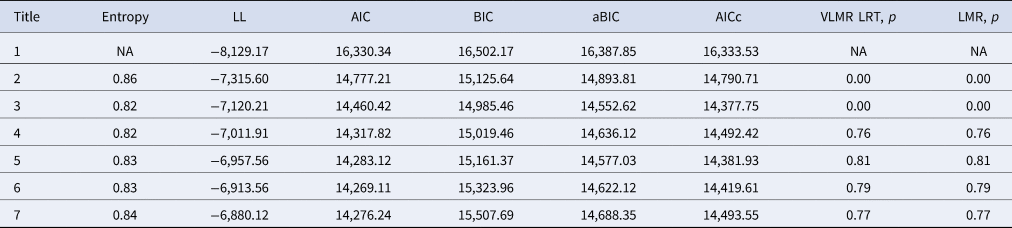

In applying LCA, the first step in the modeling process was to identify the number of latent classes by fitting models with different numbers of latent classes, and assessing the quality of fit and interpretability of the latent class structure. Seven LCA models (consisting of 1–7 classes) were run and assessed for goodness-of-fit using VLMR LRT, LMR-A AIC, AICc, BIC, and SSA-BIC. The fit indices for each of the seven latent class models are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Goodness-of-fit indices for testing seven subsequent latent class models (religiosity)

BIC, Bayesian information criterion; SSA-BIC, sample-size-adjusted BIC; AIC, Akaike information criterion; AICc, finite sample-corrected AIC; VLMR LRT, Vuong–Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio test; LMR, Lo–Mendell–Rubin-adjusted likelihood ratio test; p, p value.

The VLMR LRT and LMR-A were statistically significant for the two- and three-class models but not for the four-class model. This suggests that model fit did not significantly improve when a fourth class was added to the model, and that the three-class model would be preferable. Also, the lowest values of BIC, SSA-BIC, and AICc indicated that a three-class solution fits the data best. The entropy of the three-class model was 0.82, indicating the high level of reliability of this solution.

Table 3 shows the conditional item probabilities for each class in the three-class religiosity model. Class 1 is internally quite diverse. Although the Catholic respondents declared themselves to be members of the RCC and as believers, the majority of people in this class felt distanced toward their basic beliefs and the Church was assessed critically. Taking into account other studies of religiosity, it can be assumed that this class corresponds to the characteristics of an eclectic religiosity which is cultural at its core, and that is nominal in its nature and characterized by low-level institutionalization. For the purposes of this study and taking into account the criterion of conformity to the demands of the Church, we termed this class as weakly institutionalized religiosity.

Table 3. Proportion and conditional probabilities of responses for the three latent classes (religiosity)

Note. Gray shading indicates probabilities greater than 0.10.

The respondents in class 2, who made up the largest group in our sample, almost without exception identified themselves as believers. The intensity of their beliefs within the framework of the individual indicators of religiosity, and thus also their conformity to the expectations of the Church, was higher than that in class 1, but definitely lower and less consistent than that in class 3. These respondents presented a type of religiosity closer to the orthodox model than class 1, but inconsistently. Apart from declarations of affiliation and of being religious, each of the other indicators revealed a significant probability of beliefs that are inconsistent with the teachings and expectations of the Church. This is a type of selective, partially orthodox religiosity; hence we call it moderately institutionalized religiosity.

The last, class 3 presents the type of religiosity most consistent and closest to the RCC teachings. In fact, it is characterized by a very high degree of compliance with RCC expectations; the type of religiosity in this class is institutionalized to the highest degree in line with the authority and teaching of the Church. Given these characteristics, we called this type the strongly institutionalized religiosity.

An analysis of the socio-demographic determinants of the three distinguished classes of religiosity can be found in Appendix 1.

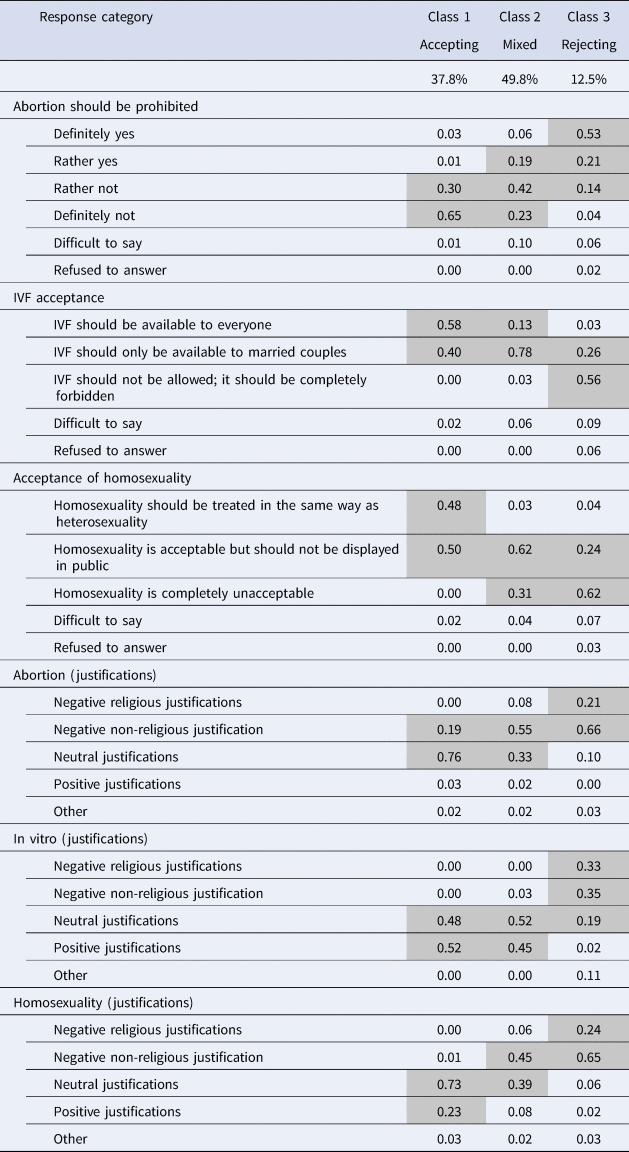

3.2. Three classes of biopolitical orientation

Table 4 presents the measures of model fit for models with one, two, three, four, five, six, and seven classes. The AIC suggests that models with increasing numbers of classes report better model fit. The aBIC suggests that the optimal solution is a model with five classes. The choice of six classes is indicated by the AICc. The p-values for the likelihood ratio tests (VLMR LRT and LMR-A) and lowest values of two information criterion indices (BIC) favored a three-class solution. Thus, we selected the three-class model. Note that the three-class models also had high classification quality (entropy = 0.78), indicating reliable classification.

Table 4. Goodness-of-fit indices for testing seven subsequent latent class models (religiosity)

BIC, Bayesian information criterion; SSA-BIC, sample-size-adjusted BIC; AIC, Akaike information criterion; AICc, finite sample-corrected AIC; VLMR LRT, Vuong–Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio test; LMR, Lo–Mendell–Rubin-adjusted likelihood ratio test; p, p value.

Table 5 shows the conditional item probabilities for each class in the three-class model. The first class (comprising 37.8% of all Catholics surveyed) is characterized by relatively liberal orientations toward the three biopolitical themes. The representatives of this class make almost no use of the negative meanings ascribed to each topic. The exception is abortion, where the conditional probability of indicating negative terms (of non-religious nature) is relatively high (0.19). In general, the views of this group of respondents can be labeled as moderately accepting and neutral or positive in the axiological perspective. We shall refer to this class as the accepting orientation.

Table 5. Proportions and conditional probabilities of responses for the three latent classes (orientation toward biopolitical themes)

Note. Gray shading indicates probabilities greater than 0.10.

The second class, further referred to as that of mixed orientation (partly accepting/partly rejecting), includes almost half of the respondents (49.8%) and presents a more conservative (less liberal) approach to the topics analyzed. The higher level of conservatism is evident in the greater likelihood of using negative terms to describe two of the three topics, namely abortion and homosexuality. In relation to IVF, neutral terms are used more often than negative ones.

The third class (comprising 12.5% of all respondents) groups respondents with clearly conservative beliefs who reject abortion, IVF, and homosexuality. Additionally, while defining each of the three topics we observed a more frequent use of negative meanings. It is worth noting, however, that even in this group the probability of using negative terms of a non-religious nature is greater than that of negative terms derived from strictly religious language, even though only in this class is the use of negative terms with religious connotations higher than 0.10. This class is referred to as the rejecting orientation.

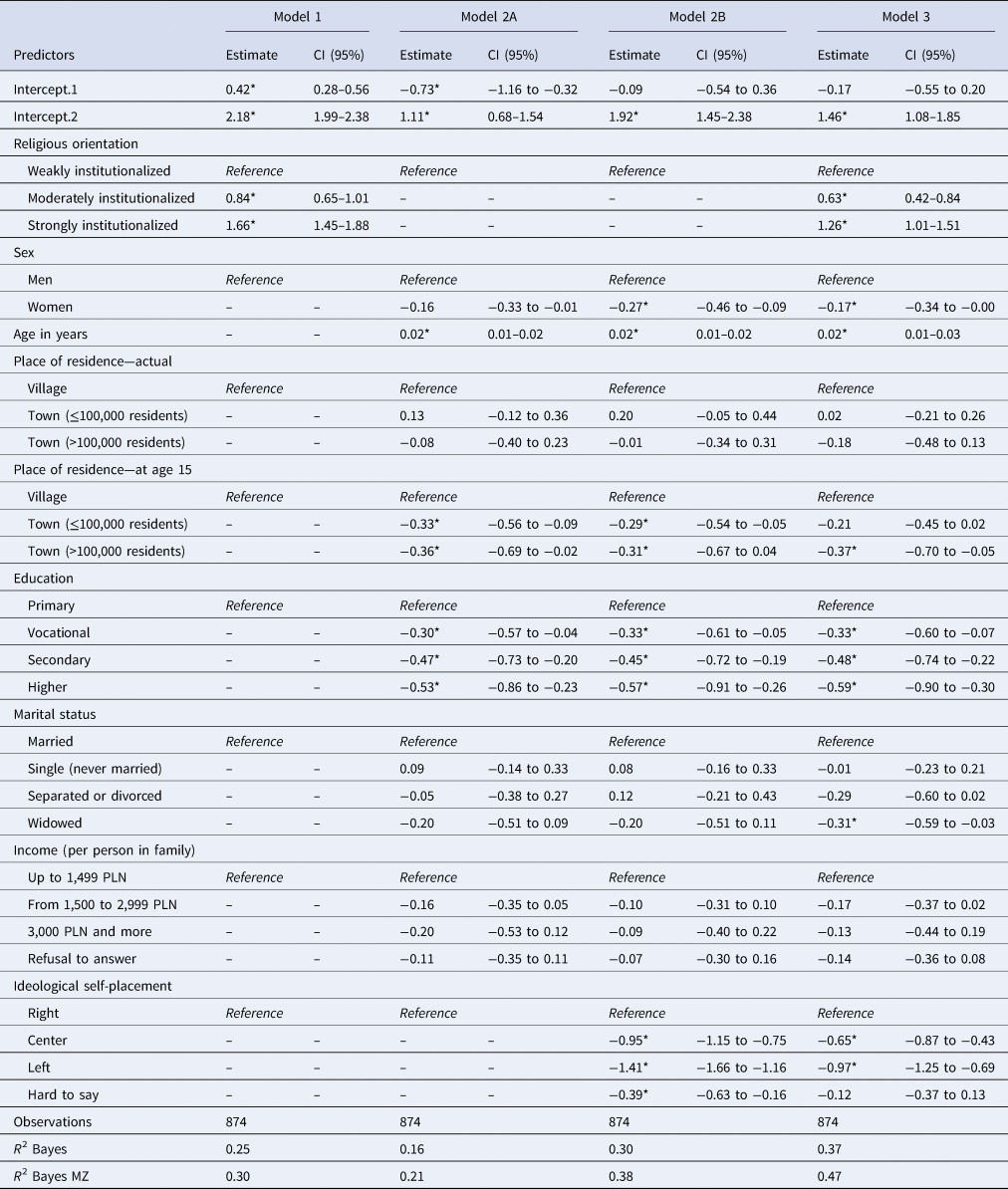

4. Religiosity as a predictor of orientation toward biopolitical themes

An ordinal regression analysis was used to verify the relationship between biopolitical orientations and religiousness among the Catholics in the sample (Table 6). The respondents' being divided into three clusters based on the LCA was treated as an independent variable. Only one independent variable was included in model 1, i.e., classes of religiosity characteristic of the Polish Catholics. In model 2A seven socio-demographic variables were used as predictors: gender, age, the type of locality in which the respondent currently lived, the type of locality in which the respondent lived at the age of 15, education, marital status, and income (religiosity was not included in the model). In the next model (model 2B), ideological self-placement (on the right-left axis) was included. In the last model (model 3), the respondents' class of religiosity was also included in the independent variables (nine predictors in total).

Table 6. Effects of covariates on orientation toward biopolitical themes (ordinal regression)

Note. Estimate, posterior means of the regression parameters; CI (95%), lower and upper bounds of the 95% credible intervals.

*p < 0.05.

As expected, religiosity (with no other variables included in the model) can (model 1) predict orientations toward biopolitical themes, explaining over 20% of the variance in the dependent variable. The analysis of the model 2A results indicates that of the seven socio-demographic variables, five are associated with orientations toward biopolitical themes, i.e., gender, age, type of residence at age 15, education, and marital status. A lower level of conservatism was displayed by women, younger people, and those who had lived in large cities at age 15 (compared to those raised in rural areas), respondents with basic vocational, secondary, or higher education (compared to respondents with primary education), and widows and widowers (compared to married respondents). The variables included in the model explain just over 16% of the independent variable. Inclusion of ideological self-placement on the right-left axis in the next model (see model 2B) significantly increased the percentage of explained variance (it almost doubled to 30%). Declaring centrist and left-wing beliefs (as well as no explicit beliefs on the right-left axis), compared to declaring right-wing beliefs, is associated with a lower likelihood of being of the rejecting biopolitical orientation.

In the last regression model (model 3), religiosity classes were additionally included (in addition to the socio-demographic variables and ideological self-placement). As was the case in model 1, when controlling for socio-demographic-political variables religiosity classes also turn out to be a significant predictor of biopolitical orientations. Moderately institutionalized religiosity and especially strongly institutionalized religiosity, unlike weakly institutionalized religiosity, were associated with a significantly higher probability of being assigned to a conservative biopolitical orientation. This model managed to explain as much as 37% of the variance in the independent variable (i.e., 7% more than in the previous model, which included only socio-demographic variables and ideological self-placement on the right-left axis).

5. Discussion of the main findings

The main purpose of the study was to determine the nature of the differences among Catholics in Poland, and the relationship between the types of religiosity and biopolitical orientations, as revealed by applying a person-centered approach, i.e., LCA, on the basis of research conducted on a large, nationally representative sample. The analyses revealed an internal pluralism of RCC members and allowed for the identification of three clusters of Polish Catholics with varying degrees of institutionalized religiosity (weakly, moderately, strongly institutionalized) and three types of orientations toward biopolitical issues, showing variation in the degree of acceptance–rejection of IVF, abortion, and homosexuality.

The results of the regression analysis showed that while internal religious diversity among Polish Catholics is little affected by socio-demographic variables, it is strongly associated with ideological self-placement. It seems interesting that religiosity is significantly more strongly differentiated by division on the left-right axis than by the respondents' socio-demographic characteristics. This may result from a weakening of socio-demographic differences associated with (1) an increasing level of education (between 2000 and 2018, Poland experienced the largest increase across the European Union in the proportion of young people obtaining a tertiary diploma (by 33 percentage points)) (Jakubowski, Reference Jakubowski and Crato2021); (2) blurring of the differences between city and countryside (migration processes no longer only from the countryside to cities, but also vice versa) (Ilnicki, Reference Ilnicki2020); deagrarianization of rural areas (Rosner and Wesołowska, Reference Rosner and Wesołowska2020); progressing periurbanization (Idczak and Mrozik, Reference Idczak and Mrozik2018), and (3) homogenization of social consciousness influenced by the mass media, including the internet. The internet contributes to democratization of the religious scene, removing or weakening the significance of socio-demographic variables such as place of residence, gender, or age. As a result of the structural processes of socio-economic and cultural change, religion is becoming more weakly “rooted” in particular social segments—above all it is a matter of individual choice.

Strongly institutionalized Catholics show a clear tendency to place themselves more on the right of the political spectrum than Catholics whose model of religiosity to a greater or lesser extent deviates from the expectations of RCC, which is in line with the results of previous studies (Piurko et al., Reference Piurko, Schwartz and Davidov2011). This is particularly the case in the countries (like Poland) with a major national religion (Caprara et al., Reference Caprara2018).

Ideological self-placement also proved to be important when it came to orientation toward biopolitical topics. Our analyses confirm the previous findings insofar as people with right-wing beliefs display higher levels of prejudice (negative emotions and attitudes) and intolerance (denial of rights) toward various social groups (e.g., gay/lesbian) than people with left-wing political beliefs (e.g., see Sibley and Duckitt, Reference Sibley and Duckitt2008, for a meta-analysis). At the same time, the regression analyses indicate that, independently of socio-demographic variables and ideological self-placement, belonging to a given class of religiosity significantly differentiates the respondents' orientations toward biopolitical topics. In general, the closer religious orientations are to the demands of the church, the more strongly they reflect the RCC teaching on biopolitical topics.

These findings justify the conclusion that the RCC has the capacity to have an impact on internally consistent cognitive perspectives which translate into ideological orientations. Given that in Poland, similarly to other countries (Esmer and Pettersson, Reference Esmer, Pettersson, Dalton and Klingemann2007; Ignazi and Wellhofer, Reference Ignazi and Wellhofer2013; Langsæther, Reference Langsæther2019; Scherer, Reference Scherer2020; Torgler et al., Reference Torgler, Stadelmann and Portmann2020), religiosity and the related ideological orientations translate to electoral behavior (Grabowska, Reference Grabowska2004; Jasiewicz, Reference Jasiewicz, Materski and Żelichowski2010; Żerkowska-Balas et al., Reference Żerkowska-Balas, Lyubashenko and Kwiatkowska2016; Zagała, Reference Zagała2020), the Church can be considered a central actor on the political scene throughout the entire period of political transformation in Poland after 1989 (Tatarczyk, Reference Tatarczyk, Glatzer and Manuel2020).

However, it seems that the Church's ability to display cohesion and maintain discipline among members as one form of influence on public life (Wald et al., Reference Wald, Owen and Hill1990; Ganghof, Reference Ganghof2003; Fink, Reference Fink2009; Potz, Reference Potz2020), is limited, since even in the case of strongly institutionalized religiosity (28% of all Catholics) only slightly more than half of the respondents shared its rejectionist stance on IVF, abortion, and homosexuality; and even in this group, the respondents used almost no justifications derived from religious language. Other respondents were found to be closer to a mixed orientation (partly accepting/partly rejecting). This may be related to the variation in social expectations with regard to the roles played by the Church, as observed in other studies, including the fact that its undertakings in solving social problems (such as poverty, education) win wider support than those concerning the moral sphere (Tomka, Reference Tomka2011). Also, the direct influence of the Church on politics is often questioned (Ančić and Zrinščak, Reference Ančić and Zrinščak2012).

What picture of Catholicism in Poland emerges from these analyses in the perspective of broader religious transformations in Europe? How to interpret the religiosity of more than 30% of weakly institutionalized Catholics who, on the one hand, declare belonging to the RCC but, on the other, attribute almost exclusively negative functions to it (a significant portion of moderately institutionalized Catholics do the same) and reject not only the teaching related to biopolitical topics but also, for example, a belief in salvation? In the authors' opinion, this points to a process of deinstitutionalization and privatization of religion (Luckmann, Reference Luckmann1967) and the features of religiosity of this group can be seen as similar to the category of “fuzzy fidelity” suggested by David Voas, the representatives of which, in his opinion, are neither religious nor non-religious (Voas, Reference Voas2008)—they may reject the belief in salvation, but will participate in the traditional Easter celebrations. On the contrary, in Poland, unlike in Western Europe, belonging is unquestionably more important to Catholics than believing (Davie, Reference Davie1994), which seems to result from the historical connection between Catholicism and national identity (Zubrzycki, Reference Zubrzycki2011), even though in recent years it has sometimes taken an extreme, nationalistic turn (Kotwas and Kubik, Reference Kotwas and Kubik2019).

Paradoxically, but as predicted by Beyer (Reference Beyer and Borowik1999), two parallel (seemingly contradictory) processes can be observed in contemporary Poland: the privatization of religion, and the intensified presence of the Catholic Church in the public space. The privatization of religion stands for a departure from ecclesiastical orthodoxy and pluralism within Catholicism. However, only the weakly institutionalized can be placed in the category of people who, without losing their place in the chains of the collective memory, seem to be open, at the individual level, to non-institutional modes of believing (Hervieu-Léger, Reference Hervieu-Léger2000) or forms of religion defined by Roberto Cipriani as “diffused” (Cipriani, Reference Cipriani2017). Meanwhile, interpretations of the transformation of religiosity in Western Europe emphasize a transformation involving the erosion of ties to churches and the spread of alternative forms of religiosity away from its institutional forms (Davie, Reference Davie2000; Heelas, Reference Heelas2005, Reference Heelas2008; McGuire, Reference McGuire2008; Ammerman, Reference Ammerman2013).

Paradoxically, as these analyses show, the distancing of the Polish society from institutional religion and the RCC's coherent and integrated stance toward biopolitical topics is accompanied by an intensified presence of the Church in public space, including in the discourses on biopolitics. Interestingly, studies of these discourses indicate that the Church often uses arguments from outside the resources of religion, such as defense of “the natural order,” “human nature,” or “protection of Polish nation” and “traditional family and family values” (Kościańska, Reference Kościańska2014; Koralewska and Zielińska, Reference Koralewska and Zielińska2022).

On the one hand, this phenomenon can be seen as meeting the condition of post-secular societies, namely the “translation” of religious arguments into secular language (Habermas, Reference Habermas2008), which broadens the scope of their potential influence. Habermas argues that in “post-secular” societies, Churches and other religious organizations, while losing their direct links with the state and political sphere, do not lose their significance in the public space. Similarly in this respect to Casanova's thesis (1994) on deprivatization of religion, he argues that churches could be formative in public discourses concerning moral matters (like biopolitics itself) by playing a role which he calls “communities of interpretation” (Habermas, Reference Habermas2008, 5).

Therefore, expanding the vocabulary of arguments used by borrowing some of them from secular language, such as the “human nature” or “family values” cited above as well as others like “human rights,” could be interpreted (not exclusively) as “translation” from religious terms, helping to meet the requirements of secular conditions forming the public space. In such a discourse, for instance, “family values” in religious terms would be legitimized by the sanctity of the sacrament of marriage guaranteed by God, while in secular terms it would be linked to the integration of family, health of their members, and so on. In this way, the RCC (and other religious actors) play a dual role: in the religious field as an interpreter of God and in the public space as a “community of interpretation,” using and/or converting the meanings of the opponents in discourse. A question arises here regarding the motivation of religious actors. Is it, as Habermas's normative vision predicts, motivated by the cognitive will to search for mutual understanding of religious and non-religious actors playing in the public space (vis-à-vis the neutral state (Habermas, Reference Habermas2006, 4–5); or rather a way of reaching hegemony in discourse by appropriation and reinterpretation of “secular” arguments (Laclau and Mouffe, Reference Laclau and Mouffe2001).

On the other, this would be a strategy similar to that noted by Enzo Pace in the case of the RCC in Italy and Spain, resulting, in his view, from the adaptation of the religious system to the changed conditions of communication with the outside world and from the assumption that non-believers, and detached and nominal Catholics, can be reached not by the religious language but by a universal “ethics for all” code (Pace, Reference Pace and Ammerman2007, 44–45). Perhaps this is the reason why “sin” was hardly used by our respondents as a term in connection with abortion, IVF, or homosexuality. If so, this would indicate that religious language, even among declared Catholics, is losing its power to legitimize the sphere of moral decision making. A third explanation is also possible, suggesting that the RCC in Poland takes on the secular arguments in order to take over the entire discursive field with its teachings, and maintain its hegemonic positions.

These findings must be interpreted in the light of several methodological limitations. First, the data are single cross-sectional, which precludes any definite inferences about changes in the religiosity and orientation toward biopolitical topics over time, and does not allow for a clear distinction between age, cohort, and period effect (Fienberg and Mason, Reference Fienberg, Mason, Mason and Fienberg1985), which is central to the theories of religious change in modern societies (Schwadel, Reference Schwadel2010). Consequently, future studies should use repeated cross-sectional (Yang and Land, Reference Yang and Land2006, Reference Yang and Land2013) or longitudinal (Grygiel and Humenny, Reference Grygiel and Humenny2012) research design.

The authors are also aware that their conceptualization of religiosity, although it fulfills the postulate for expanding the number of indicators in the research on the relationship between religiosity and attitudes toward biopolitical topics (Adamczyk et al., Reference Adamczyk, Kim and Dillon2020) is pen to improvement. Each of the indicators included (identification, statements of faith, beliefs, religious practices, attitudes toward the Church) could be represented more broadly by a larger number of questions. We assume that the continuation of the research could be more closely related to a specific conception of religiosity and its parameters, as this trend has been developed in the sociology of religion in recent years (Pollack, Reference Pollack2003, Reference Pollack2015; Stolz, Reference Stolz2009).

Also, the choice of biopolitical topics could be much broader than the one we have made. Answers to today's topical questions, for example, how to address the threats of climate change, aging populations, or genetically modified foods are part of the teaching of religious institutions and may be related to the religiosity of their members (Omobowale et al., Reference Omobowale, Singer and Daar2009; Haluza-DeLay, Reference Haluza-DeLay2014). Examining these relationships more broadly could allow for better substantiated conclusions about the weak position of religious concepts in legitimizing moral choices.

The questions used for estimating the respondents' orientation regarding biopolitical topics focused on determining their general acceptability. We therefore asked about their general attitude to the three phenomena, leaving it to the respondents to interpret what abortion, IVF, and homosexuality mean. In the questions we therefore did not indicate, for example, the month of the pregnancy in which the abortion would take place or additional circumstances that might make the procedure possible, e.g., rape, an incurable disease of the fetus, a difficult material situation of the mother, and so on (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Jelen and Wilcox1992; Sahar and Karasawa, Reference Sahar and Karasawa2005). We also did not differentiate the aspects of permissibility of IVF (sex selection, allowing IVF for same-sex couples or single women) or homosexuality (e.g., acceptance of adoption of children by same-sex couples) that might affect the level of their acceptance (Craig et al., Reference Craig, Martinez, Kane and Gainous2005; Hendriks et al., Reference Hendriks, Dancet, Vliegenthart and Repping2017). The method we used, apart from its benefits (the possibility of determining general orientations based on a lower number of questions and comparability of orientation regarding all three topics), also has drawbacks. One of these is the possibility of the respondents having different understandings of each biopolitical issue: abortion, IVF, and homosexuality. In future research, it would therefore be good to consider more differentiated indicators for identifying latent classes in order to increase the accuracy of the estimated relationship between the phenomena.

6. Conclusions and implications

Our analyses yield important conclusions both for theoretical considerations in the sociology of religion, and for the interpretation of the religious situation in countries similar to Poland, dominated as it is by one specific religious tradition (Catholicism) which is strongly associated with national identity.

In Poland, as in many other Central and Eastern European countries (e.g., Romania, Croatia, Russia) that experienced communism and the transformation after its collapse, the indicators of religiosity and the relationship between religion and national identity are stronger than in Western Europe (Diamant and Gardner, Reference Diamant and Gardner2018). The level of conservatism in relation to the biopolitical issues analyzed is also higher (Yatsyk, Reference Yatsyk2019), particularly in relation to homosexuality (Diamant, Reference Diamant2020) and the permissibility of abortion (Salazar and Starr, Reference Salazar and Starr2018). According to our findings, it turns out that not only is the level of religiosity related to the type of orientation toward abortion, IVF, and homosexuality, but also that both religiosity and attitudes toward biopolitical topics are strongly related to ideological self-placement. This intertwining of religion, ideology, and biopolitics in post-communist Europe seems to be stronger than in Western Europe not only because of the greater influence of the churches, which saw new opportunities opening up after the fall of communism (through the use of the media, alliances with right-wing/national political groups), but also because of the higher level of insecurity in these societies, which have been subjected to rapid changes in all areas of life (Norris and Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2004; Sztompka, Reference Sztompka and Alexander2004).

We believe that the research presented has important implications for our understanding of religious pluralism and the possibilities of using this concept in research. First, the concept allowed us to accurately portray Catholics in Poland, whose religiosity turned out to be highly differentiated, along with their attitudes toward abortion, IVF, and homosexuality. Second, the category of religious pluralism can be applied not only to countries that are religiously diverse (as is the case in mainstream research) but also religiously homogeneous.

Such diversity could be seen as one of the effects of functional differentiation of modern societies, the changing religious sub-system and its relationship with other societal sub-systems such as politics, education, culture, media, law, and so on (Luhmann, Reference Luhmann2013; Beyer, Reference Beyer2020). The growing complexity of the world, accompanied by globalization, mobility, development of social media, individualization, and so on, put pressure on religion to adapt structurally and functionally to the rapidly changing environment. The outcomes of these processes are multidimensional and frequently contradictory. From this perspective, differentiation of the religiosity of Catholics in Poland and of their stance toward biopolitical issues could be interpreted as a feature of secularization, resulting in what Dobbelaere calls pillarization (Dobbelaere, Reference Dobbelaere2004), shown in a comparative analysis of debates on selected biopolitical issues in five Catholic, West European countries (Dobbelaere and Pérez-Agote, Reference Dobbelaere and Pérez-Agote2015; Dobbelaere et al., Reference Dobbelaere, Pérez-Agote, Béraud, Dobbelaere and Pérez-Agote2015).

The authors of the case studies show the interplay of the sub-system of law and the “church” in the construction of discourses on abortion, IVF, euthanasia, and same-sex marriages in Belgium, France, Spain, Portugal, and Italy. Importantly, the “church” is understood here broadly, including hierarchs, institutions such as universities or hospitals, Catholics as members of the Church, but also groupings and movements. These are all actors in the construction of the debate on these ethical issues, which results in a particular legal outcome, i.e., a law concerning a given biopolitical topic. The analysis and then comparison of the case studies show that nothing is taken for granted: neither understanding of religion, Catholicism, nor a particular biopolitical issue. Initiatives of introducing/changing the law are a challenge for every side engaged in the social negotiations and conflict finally leading to a legal outcome. We are referring to this publication because it shows, from a different perspective and with a different methodology from ours, the complexity of “collective construction and reconstruction, contestation and affirmation of common normative structures” (Casanova, Reference Casanova1999, 37), to which the biopolitical issues we analyzed belong, as well as how understanding the role of religion and the Church is socially negotiated in modern societies.

Polish society continues to be in a process of transformation, still influenced by both the collapse of communism in 1989 and accession to the European Union in 2004, as well as by global processes that have an impact on societal sub-systems, including biopolitics and religion. We indicated above different possible characteristics in interpreting differentiation of religiosity and biopolitical orientations and complicated patterns of relations between the two. Differentiation of Catholics is also mirrored in public debates, most visibly in the controversies surrounding abortion and homosexuality. Organizations and movements supporting the official line of the RCC are currently well organized and active, while the liberal wing is less visible. There are, however, some signs of revival from this side, while society as a whole is changing, including the image of the role played by religion and the RCC.

Most members of the RCC hierarchy in Poland either do not understand the social processes going on in society, including yet majority but—as we showed—differentiated Catholics, or entirely reject them (Borowik, Reference Borowik2002). This is indicated not by their conservative position—based on the doctrine concerning biopolitics, which is understandable—but by the way in which they communicate: language of exclusion, threat, lack of respect to other-minded individuals and to social sub-groups (like children born thanks to IVF, LGBTQ+ people, politicians choosing their own will as the source of decisions in voting on biopolitical issues, etc.) participating in public discourses (Radkowska-Walkowicz, Reference Radkowska-Walkowicz2012; Korolczuk, Reference Korolczuk2016; Hall, Reference Hall2017; Żuk and Żuk, Reference Żuk and Żuk2020). Taking into account the controversies surrounding the RCC in recent years (Ramet, Reference Ramet, Ramet and Borowik2017, 31–35), including pedophilia in the Church, and close relations with the right-wing coalition in power since 2015, it is rather surprising that differentiation of societal attitudes toward religion and distancing from the Church is not more dynamic.

The example of Poland illustrates the significance of intra-religious pluralism and its implications for the attitudes toward biopolitical topics, becoming a potential source of political divisions. This could mean that empirical diversity within one religious tradition may serve as a substitute for structural pluralism.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048323000093.

Financial support

Funding for this research was provided by the Narodowe Centrum Nauki (2014/13/B/HS6/03311). All conclusions are solely those of the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare none.

Irena Borowik is a professor of sociology in the Institute of Sociology, Jagiellonian University, Poland. Her scientific interests include diverse fields of the sociology of religion, including theories of religion, empirical research on religiosity, religious change under condition of transformation in Central and Eastern Europe, connections between religion and biopolitics, and methodological issues. She has authored numerous books and articles, in Poland and abroad.

Paweł Grygiel is a sociologist, professor at the Institute of Pedagogy of Jagiellonian University (Kraków, Poland). He has been academically focused on the relationship between social isolation/integration and well-being (especially among adolescents and psychiatric patients), contemporary changes in religiosity, as well as the analysis of psychometric properties of research scale, their adaptation, and practical use of modern statistical methods (factor analysis, path modeling, structural equation models, latent class analysis, network analysis, etc.) in the social sciences.