LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article you will be able to:

• demonstrate a clear idea of the history behind Present State Examination and its development

• describe the current state of phenomenology and psychopathology in the UK's psychiatry curricula

• understand the importance of incorporating detailed phenomenology in training and clinical practice.

Psychopathology, phenomenology and nosology

Psychopathology

Psychopathology is the discourse (logos) about the sufferings (pathos) that affect the human mind (psyche) (Stanghellini Reference Stanghellini2013). The discipline of psychopathology focuses on the subjective abnormal experiences of a patient in first-person perspective. Descriptive psychopathology does not delve into the roots or genesis of the experience but takes a ‘bottom-up’ approach in elaborating the patient's world in the patient's words and personal description. In a way it could be described as putting oneself in the patient's shoes.

Psychopathology includes the study of symptoms but it is not reducible to this kind of study (Stanghellini Reference Stanghellini, Broome and Fernandez2019). Whereas symptomatology is strictly disease or illness oriented, psychopathology is person oriented since it attempts to describe a patient's experience and their relationship to experiences and the world.

Jaspers’ General Psychopathology (Jaspers Reference Jaspers, Hoenig and Hamilton1913) was the first systematic description of abnormal mental phenomena, presented against a corresponding descriptive background of normal experience.

Phenomenology

Andrew Sims in his traditional text (Sims Reference Sims1988) describes psychopathology as the systematic study of abnormal experience, cognition and behaviour. Descriptive psychopathology is deemed to be the categorisation of these experiences and observations without theoretical explanations. Sims describes phenomenology as the observation and categorisation of abnormal psychic events, the internal experiences of the patient and their consequent behaviour.

Hence, a phenomenological approach to psychopathology does not exclude the possibility or usefulness of viewing abnormal phenomena as symptoms caused by a dysfunction to be treated. However, the phenomenological approach explores lived experience and personal meaning, alongside the hunt for causes (Stanghellini Reference Stanghellini, Broome and Fernandez2019). Stanghellini et al also use the term ‘phenomenological psychopathology’ and consider this to be at the heart of psychiatry (Stanghellini Reference Stanghellini, Broome and Fernandez2019).

The notable point in descriptive psychopathology is the distinction between form and content. A mental health professional should be concerned with both, but from a phenomenological – and consequently diagnostic – point of view the identification of form is central. A patient elaborating on external voices of neighbours, whom she cannot see but hears talking about her in derogatory terms is describing a very different experience from a patient who describes having ruminative thoughts of being bad and worthless. Although the content is similar, the form is different and influences our understanding of what the patient is exactly going through.

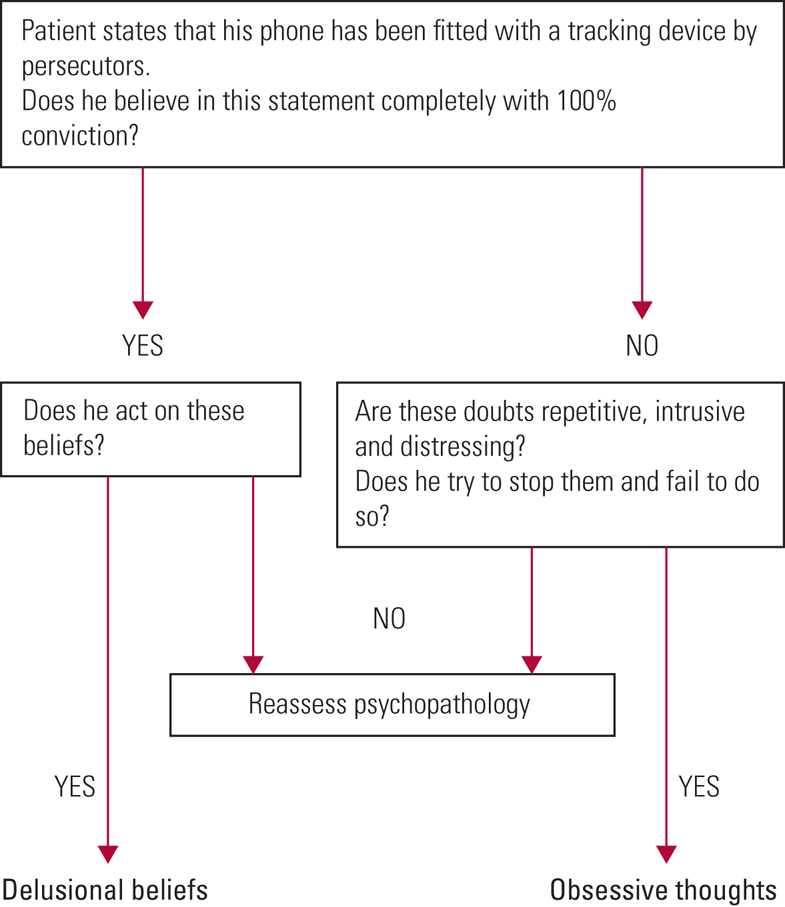

Or consider the example of a young man who goes to the police station alleging that his mobile phone has been hacked and demands for it to be examined by experts, and then takes their refusal to mean for sure that they are conspiring with his persecutors. Compare this with the example of another young man who cannot help checking his phone by taking it apart to look for a spying chip, keeps ringing his father for reassurance that he is not being spied up on and comes to his doctor for help because he is distressed by his own thoughts and understands that the problem lies in his repetitive, intrusive pattern of thinking, which is clearly illogical but difficult to stop despite his best efforts. They are describing two very different forms – delusions and obsessive thoughts respectively – which if not elicited appropriately could lead to misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment. The first young man considers what is being done to him by other people externally as the source of his problem. The second recognises the painful, repetitive, intrusive nature of his thoughts and what is happening inside his head as the problem. However, even before a diagnosis is reached, it would be a missed opportunity not to understand the patient from their perspective and respect their feelings, distress and experience (Fig. 1).

FIG 1 Clarifying the phenomenological psychopathology in the case of a patient who believes that his mobile phone has been hacked.

Clarifying phenomenological psychopathology: nosology

Identification of complex psychopathology can be confusing when it is carried out without attention to definitive details. For example, thought broadcast is an experience difficult to understand because it is so different from the usual range of human experiences. Surveys of psychiatrists (Pawar Reference Pawar and Spence2003) have shown a difference of opinion that need not happen if there were more discussion and consensus about what they actually mean by this phenomenological term.

Hence, the need to operationalise experiences and the need for a common language led to further developments in clinical practice in the 1950s and 1960s. However, the descriptive element of phenomenology still remains important. Unless we describe and agree on a description of what constitutes a ‘delusion’, the inclusion of delusions within operational criteria for diagnoses will hold little meaning.

Nosology is the study of classification of diseases. Psychopathology helps identify abnormal experiences, hence identifying symptoms that can be used for syndromal classification. However, the role of phenomenological psychopathology is much wider. By confining their study to phenomena they deem relevant to diagnosis, research psychiatrists neglect the diverse elements of the patients’ experience (Stanghellini Reference Stanghellini, Broome and Fernandez2019). Andreasen brings up the same point when she says:

‘Since the publication of DSM-III in 1980, there has been a steady decline in the teaching of careful clinical evaluation that is targeted to the individual person's problems and social context and that is enriched by a good general knowledge of psychopathology. Students are taught to memorize DSM rather than to learn complexities from the great psychopathologists of the past. By 2005, the decline has become so severe that it could be referred to as “the death of phenomenology in the United States”’ (Andreasen Reference Andreasen2007).

Summary

In summary (Box 1), psychopathology opens up a world in which we attempt to understand a range of abnormal human experiences, irrespective of whether they are part of symptomatology of an illness or disorder. The phenomenological approach focuses on ‘putting oneself in the patients' shoes’ and trying to understand what the patient experience feels like. Nosology draws on the identification of the ‘form’ of an experience from the phenomenological approach and uses a set of symptoms in syndromal classification.

BOX 1 Some definitions

Psychopathology is the systematic study of abnormal experience, cognition and behaviour. Descriptive psychopathology is deemed to be the categorisation of these experiences and observations without theoretical explanations.

Phenomenology is the observation and categorisation of abnormal psychological events, the internal experiences of the patient and their consequent behaviour. The phenomenological approach explores lived experience and personal meaning, alongside the hunt for causes.

Nosology is the study of classification of diseases.

The history of the Present State Examination and the need for a common phenomenological language

The PSE: the first 50 years

The need for a common language for examining and interpreting psychopathology was identified in the early 1950s, leading to research conducted by the Social Psychiatry Research Unit of the UK-based Medical Research Council and producing the early editions of the Present State Examination (PSE) (Wing Reference Wing1996), a semi-structured questionnaire to examine psychopathology. By its sixth edition the PSE had sections on psychotic and neurotic symptoms. Its reliability on all domains apart from anxiety was found to be high. Agreement on clinical diagnoses made independently by the five psychiatrists taking part in the evaluation of the instrument was also high (Wing Reference Wing1996).

The sixth edition had a short life because it had to be rapidly adapted for two large international studies – the UK–US Diagnostic Project (Cooper Reference Cooper, Kendall and Gurland1972) and the International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia (IPSS; World Health Organization 1973, 1979). The results of these large international studies revealed differences in the diagnosis schizophrenia in different parts of the world, but the PSE demonstrated that clinicians using the same language for phenomenology were able to identify the same disorder more reliably. Practices of the time were such that results of studies could not be compared between centres in London and New York if hospital diagnoses were used for participant selection. The PSE demonstrated the need for a common language and the feasibility of a uniform examination being used around the world.

However, an important lesson also learned from the PSE at this stage was the need for a glossary to provide differential definitions.

Developments in diagnostic classification systems

There were parallel developments taking place internationally to improve the diagnosis and classification of mental disorders. The preface to ICD-10 (World Health Organization 1992) describes how, in the early 1960s, the Mental Health Programme of the World Health Organization (WHO) became actively involved in a programme with this aim and convened a series of meetings to review knowledge, actively involving professionals from various disciplines and various schools of thought in psychiatry, from different parts of the world. The programme stimulated and conducted research on criteria for classification and for reliability of diagnosis. A glossary was developed defining each category of mental disorder in ICD-8 (1968). The 1970s witnessed further growth in improving psychiatric classification worldwide, with expansion of international contacts and collaborative studies. Several national psychiatric bodies encouraged the development of specific criteria for classification in order to improve diagnostic reliability. The American Psychiatric Association developed its third revision of the DSM (DSM-III), which incorporated criteria into its classification system.

PSE-9 was published in 1974 and it included 140 items, each with a definition in a newly added glossary and an algorithm for diagnosis.

The SCAN

Collaboration between the WHO and the US Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration (ADAMHA) produced the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN) (Wing Reference Wing, Babor and Brugha1990), which were published in different versions between 1988 and 1994. Version 2.0 was presented at the meeting of the Association of European Psychiatrists in Copenhagen (Wing Reference Wing, Sartorius and Ustun1998: p. 17). SCAN incorporated PSE-10, thus proving to be a culmination of more than 30 years of PSE research (WHO/ADAMHA Project Steering Committee 1983).

The backbone of SCAN remains the glossary, which defines all the items of psychopathology. Extensive experience has shown that, with the appropriate training, all clinicians can apply the definitions, leading to comprehensive, accurate and technically specifiable means of describing and classifying clinical phenomena in order to make comparisons (Wing Reference Wing1996).

The entire experience of the PSE and SCAN repeatedly demonstrates the need for both a standardised psychiatric interview and a uniform way to interpret phenomenology in order to make robust diagnoses and produce research with findings that are applicable internationally.

Psychopathology and phenomenology in the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ curricula

The Royal College of Psychiatrists has a core curriculum, seven higher curricula and three endorsement curricula, which form the basis of training the next generation of psychiatrists (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2019a). The curricula outline the competencies, both clinical and non-clinical, expected of a trainee at the end of specified training. The higher curricula describe the skills and competencies required of a consultant psychiatrist in the National Health Service.

Mental state examination appears within intended learning outcome 1 of the core curriculum, which includes both history-taking and mental state examination. Although the headings for a clinical history are specified, there are no headings detailed for a mental state examination or the specific content of psychopathology that needs to be mastered.

In the general adult psychiatry higher specialty curriculum, phenomenology is mentioned once and the need to learn about psychopathology is mentioned twice with no further detail. The word phenomenology is not mentioned in the old age psychiatry curriculum and psychopathology is mentioned twice, again with no details specified. The child and adolescent psychiatry curriculum states the need to have a knowledge of developmental psychopathology just once and mentions the need to be able to treat psychopathology and understand its neurological basis. None of the curricula defines psychopathology or phenomenology, suggests reading resources or elaborates on the level of knowledge and clinical competence required. There is no difference outlined in the level of expertise in psychopathology and phenomenology between the core and specialty curricula.

In the MRCPsych examinations, classification and assessment in psychiatry occupies 25 marks out of 150 in paper A (16.67%), which is one of two papers (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2019b).

The syllabic content (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2019b) mentions ‘descriptive psychopathology’, which includes disorders of self, disorders of emotion, disorders of speech and thought, disorders of perception, movement disorders, disorders of cognition, and uncommon psychiatric syndromes. This is possibly the most detailed mention of psychopathology in the content of psychiatric training in the UK.

Of the 16-station clinical assessment of skills and competencies (CASC) exam for the MRCPsych, only five stations are focused on examination – both physical and mental state, including capacity assessment. There is no specific mention made of identification of psychopathology or phenomenological description.

Current research trends and the direction of travel: can neuroimaging replace a mental state examination?

Psychoradiology

Several studies claim that future diagnostic systems in psychiatry will move from symptom-based diagnosis and treatment to a neuroradiologically led diagnosis and interpretation of treatment response, leading to the new field of psychoradiology (Lui Reference Lui, Zhou and Sweeney2016).

However, we are still far from the day when radiology becomes the bedside need of psychiatric examination and management. Till then there remains a need for extensive research. For this research to be robust and widely applicable, the identification of participants needs to be highly accurate. This is possible only with in-depth identification of psychopathology and phenomenological description, leading to reliable diagnoses. It would be near impossible to state that a certain neuroradiological finding is pathognomonic or highly suggestive of schizophrenia unless the study participants have been accurately identified, and such identification is unlikely to have happened reliably without appropriate identification of psychotic symptoms that fulfil a diagnosis of schizophrenia. This can only be done with a thorough phenomenological approach and the correct identification of the form of experience, alongside the content.

RDoC: a new taxonomy for mental disorders

The Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) project is an initiative being developed by US National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) which demonstrates the line of thinking that in future neuroscience could be the basis of psychiatric diagnosis. According to a 2013 NIMH press release, ‘RDoC is an attempt to create a new kind of taxonomy for mental disorders by bringing the power of modern research approaches in genetics, neuroscience, and behavioral science to the problem of mental illness’ (Insel Reference Insel and Liberman2013).

The doctor–patient relationship remains an indispensable factor

There will still be the need to build rapport with the patient, in order to ensure engagement with treatment and adherence. The practice of talking to the patient in order to understand their experiences and build trust cannot be replaced with a brain scan. Neuroimaging will most likely notably change the practice of psychiatry in future, as did the advent of the first psychotropic medication in the 1950s. However, just as that did not take away the need for a doctor–patient relationship in psychiatry, it would be unrealistic to think that the need to understand patient experience will no longer be relevant in a specialty where the human mind is at the centre of all practice.

Back to basics?

Is it time to return to the basics of good clinical mental state examination and the phenomenological approach or is that now hair-splitting and irrelevant? There are three sides to the debate: the time factor, the human factor and the research factor.

The time factor

It is not unusual to come across overworked clinicians with heavy caseloads, where spending hours trying to differentiate and identify phenomenological strands seems practically impossible and a daunting task.

The other side of the coin is that early emphasis on phenomenological descriptions and increasing expertise in identifying the forms of experience would make the process a more natural part of clinical practice. Hence, the habit needs to be inculcated in the early stages of core training in psychiatry as an essential part of psychiatric practice.

With the correct phenomenological approach, clinicians are likely to reach more accurate diagnoses and consequently better outcomes for patients, ultimately leading to better use of resources and time. In an age of increased mental health awareness, good clinical examination and phenomenological identification are key in differentiating between human distress and clinical syndromes, to avoid overdiagnosis.

According to Schultze-Lutter et al,

‘[the] ongoing erosion of psychiatric phenomenology is further fostered by clinical casualness as well as pressured health care and research systems. The skill to precisely and carefully assess psychopathology in a qualified manner used to be a core attribute of mental health professionals, but today's curricula pay increasingly less attention to its training, thus blurring the border between pathology and variants of the “normal” further’ (Schultze-Lutter Reference Schultze-Lutter, Schmidt and Theodoridou2018).

The human factor

If there came a time when psychiatrists were able to diagnose patients from a functional brain scan or blood tests, would they need to talk to the patient at all for diagnosis and treatment?

The argument against this is that they should not change their practice now for what might happen in the future. Even if diagnoses were revised by neuroradiological and neuropathological definitions in the future, to know what kind of scan or investigation to refer for, the psychiatrist would still need clinical bedside skills to identify psychiatric symptoms – which in essence is the identification of a phenomenological form.

Understanding experiences that are distressing and bewildering to the patient will remain the cornerstone of building a therapeutic relationship, trust and adherence to treatment. Emphasis on psychopathology is what humanises psychiatry (Stanghellini Reference Stanghellini2013). Giving the patient an opportunity to describe their experiences in a space that is non-judgemental and encouraging, and the ability to describe these experiences in phenomenological terms, is reassuring that the most bizarre phenomena are recognised and part of the spectrum of recorded experience. The patient feels that they are not alone in their experience and, even though a delusion may be described as ‘not true’ or a hallucination as ‘not real perception’, there is the notion that they are believed in their perspective. Although their experience is not embedded in substance, it exists for them and the acknowledgement is crucial to making them feel that they are not being dismissed, ignored or ridiculed.

In Jaspers’ phenomenological view, the psychiatrist should, at least temporarily, set aside attempts to explain, interpret or treat and instead focus on the observational and descriptive task (Parnas Reference Parnas, Sass and Zahavi2013). It is important that the patient feels listened to by the psychiatrist, before the psychiatrist tells them what is to be done next.

The research factor

The current research emphasis in psychiatry is on biological parameters – genetics, neurological pathways and neuroimaging – and these are undeniably important in building our understanding of psychiatric disorders. However, these areas of research still depend on getting the right participants, without whom findings are likely to remain less defined and difficult to translate into clinical practice. In fact, it has been argued that a lack of attention to phenomenology has led to stagnation of research in psychiatry, as phenomenology is essential in identifying the phenotypes needed for empirical research (Parnas Reference Parnas, Sass and Zahavi2013).

Further, there remains the potential to link symptoms to neurological research rather than to syndromes alone, thus precisely and distinctly identifying areas of the brain that give rise to a particular experience and making the treatment more focused, even within the syndrome in question. The phenomenological approach in psychiatry need not be competing with a neuropathological or neurodiagnostic approach. The two can effectively complement each other. However, phenomenological identification needs to precede the identification of research participants contributing to the development of neurosciences in psychiatry. The second edition of Fish's Clinical Psychopathology (Hamilton Reference Hamilton1985) states in the introductory chapter that, with the growth of psychopharmacology and the development of biochemical and neurophysiological research, the need for clinical phenomena in psychiatry is greater than before. Without good clinical knowledge, research in psychiatry will be fruitless.

Despite all prophecies that psychopathology was doomed, and with neurobiological parameters having yet to show their differential diagnostic superiority and value for differential indication, psychiatric diagnosis continues to rely exclusively on the psychopathology described in DSM-5 and ICD-11 (Schultze-Lutter Reference Schultze-Lutter, Schmidt and Theodoridou2018).

A suggested way forward

Detail in curricula about minimum phenomenology that needs to be covered

The current psychiatric curricula and syllabuses make very brief mention of psychopathology and phenomenology. There is a need to expand on the details, including more specific phenomenological items and the level of knowledge that needs to be attained in different subspecialties of psychiatry and at different levels of training. For instance, there is no particular difference between the core curriculum and higher curricula in describing the depth of knowledge of phenomenology that students should acquire. At a time when curricula are being revised, this is an important aspect to be worked on.

Specific reading lists in curricula/syllabuses

Most trainees will be guided by their supervisors regarding traditional textbooks of psychopathology, but there is no compulsion to read these. Although there are practical problems in making a book ‘compulsory reading’, adding a suggested reading list to the syllabus is possible. Having a separate section on suggested reading in phenomenology gives the topic a place of its own, rather than jostling under the wide umbrella of ‘psychiatric examination’.

Although modern textbooks with chapters on psychopathology will form part of the current reading suggestions, traditional psychopathology textbooks still have their place in explaining the development of phenomenological thought. Where there are differences of opinion in descriptions, there needs to be discussion and debate. Such textbooks should include Andrew Sims’ Symptoms in the Mind: An Introduction to Descriptive Psychopathology (Sims Reference Sims1988, Reference Sims2003; Oyebode Reference Oyebode2018), Fish's Clinical Psychopathology (Hamilton Reference Hamilton1985; Casey Reference Casey and Kelly2019) and Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry Version 2.1 (SCAN, World Health Organization 1999), alongside its elaborate glossary. The current editions of Symptoms in the Mind (Oyebode Reference Oyebode2018) and Fish's Clinical Psychopathology (Casey Reference Casey and Kelly2019) are also worth a read but a comparison with the more traditional textbooks would allow a mature and in-depth consideration of how the phenomenological outlook has developed over the years. Among the newer textbooks, The Oxford Handbook of Phenomenological Psychopathology (Stanghellini Reference Stanghellini, Broome and Fernandez2019) is a valuable addition to the reading list.

Specific times allocated within training rotations to focus on psychopathology and phenomenology

The core psychiatry rotation is unique within medical specialties for having a specific MRCPsych course that must be attended by all trainees, is arranged in all training rotations and usually has a designated educator to organise and run it, with help from local colleagues. The main aim is to cover the syllabic content for the MRCPsych examinations. In recent times ‘communication skills’ has been a defined component that all MRCPsych courses have had to include. Psychopathology usually gets a day within the 3 years, or may even be subsumed within a lecture on ‘mental state examination’. There is a current need to allocate more time to different aspects of psychopathology in thought, perception and mood in detail and encourage trainees to write up case logs for their portfolio that would include a minimum number of phenomenological descriptions.

We might also think of a radical change in psychiatric rotations that makes formal training in an instrument such as the SCAN compulsory. A shortened version of the PSE could be made mandatory in core training, followed by SCAN training in higher specialty rotations. This would place a compulsion on deaneries to organise appropriate trainers who have a robust grounding in phenomenological psychopathology through a PSE background.

For career grade doctors, at least one CbD per appraisal year that focuses on complex psychopathology

The current appraisal/continuing professional development needs specify at least two case-based discussions (CbDs) with their peer groups in a year for career grade doctors. It might be suggested that at least one of these CbDs should focus on phenomenology.

Encouragement of excellent descriptive psychopathology

Detailed phenomenological descriptions, expert distinctions and detailed reviews of patient experiences need to be encouraged to promote a culture that is geared towards good depth of phenomenological description that students can demonstrate. This could be promoted by national, regional and local awards for anonymised descriptive write-ups, promotion of ‘psychopathology clubs’ and collection of rich anonymised material locally or nationally to form a ‘register’ that can be referred to for examples of phenomenological items. For example, ‘delusional perception’ is a rare phenomenon. When a psychiatrist comes across an example, this could be passed on to the register to form a part of shared training material. Such a register of real-life patient experiences could be held by the Royal College of Psychiatrists. The best description(s) could attract an annual prize, but the entire list of accepted descriptions could be part of this register. For inclusion on the register, the descriptions should be peer reviewed. The authors would be expected to describe the patient experience and identify the phenomenological psychopathology.

There could also be conferences/seminars organised by the Royal College of Psychiatrists focused specifically on phenomenological psychopathology.

Promoting change in culture: bring psychopathology into the limelight

An initial push to bring psychopathology into the limelight is needed. A recent keynote presentation by Femi Oyebode, Professor of Psychiatry at the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ International Congress in 2019 (Psychopathology: The Foundational Discipline of Psychiatry) is a step in the right direction. However, to bring descriptive psychopathology and phenomenology back to their deserved place in clinical practice, there needs to be more space and prominence. A generation of trainees has possibly grown up in a culture of physical health monitoring and risk assessment forms. Although there is no denying the importance of these, there has to be acknowledgement that phenomenological descriptions form the foundation of psychiatric practice.

Possibilities include conferences focused only on phenomenology, debates and discussions, promotion of research in descriptive phenomenology, phenomenology newsletters or special editions of journals dedicated to phenomenology and descriptive psychopathology.

One could hope that, after an initial drive, if the ‘culture’ has picked up, an emphasis will follow during case discussions, ward rounds and supervision.

Collaborative thinking between neuroscience and phenomenology

Research suggests that passivity phenomena could be analogous to somatophrenia (Spence Reference Spence2010) in parietal lobe pathology – that the mind not recognising the origin of motor acts is similar to the mind not recognising the body in its substantive form. Similar discussion and research could modernise phenomenology and promote the dialogue in mind–body holistic thinking.

In fact, the NIMH press release on RDoC mentions that all medical disciplines advance through research progress in characterising diseases and disorders. DSM-5 and RDoC represent complementary, not competing, frameworks for this goal:

‘As research findings begin to emerge from the RDoC effort, these findings may be incorporated into future DSM revisions and clinical practice guidelines. But this is a long-term undertaking. It will take years to fulfill the promise that this research effort represents for transforming the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders’ (Insel Reference Insel and Liberman2013).

The future of psychiatry thus lies in the hands of a type of psychopathology that we should call integrative psychopathology. The main tasks of psychopathology can only be pursued in close cooperation with other branches of science interested in studying psychiatric issues. Whereas contemporary psychopathology must lay the foundations for that cooperation, integrative psychopathology must be complemented by further advancements in theoretical psychopathology, so as to enable new conceptual developments, which can then be fruitful for cooperative research and psychiatric clinical practice (Musalek Reference Musalek, Larach-Walters and Lépine2010).

The overall message from various sources is that neuroscience and phenomenological psychiatry need not compete but should rather complement each other.

Working together with patient and carer groups

In a process that puts the patient at the heart of trying to comprehend human experience, without analysing or judging, the involvement of patient and carer groups in the drive is crucial to bringing descriptive psychopathology the recognition it deserves.

Conclusions

Psychopathology and phenomenology have been time and again highlighted as cornerstones in psychiatric practice (Hoff Reference Hoff2008; Stanghellini Reference Stanghellini and Broome2014, Reference Stanghellini and Fiorillo2015).

We are not at a stage where we have a superior, more effective clinical approach and abandoning phenomenology prematurely will only delay further developments in psychiatry.

Even when research has progressed in a more biological direction, the need for a human touch in psychiatry, a consistent bottom-up approach and appropriate use of resources will be possible only with a solid foundation in phenomenology.

Studies such as the IPSS have shown us that phenomenological forms are found worldwide, although it is natural that the content would be culturally influenced. The universality of these experiences is proof that these descriptions are not subjective creations but valid phenomena that need to be recognised.

Although perceived ‘subjectivity’ has always been a vague undercurrent obstructing the view of descriptive psychopathology as an exact science, it can be argued that the subjectivity arises as a result of inadequate discussion and lack of depth in training. An appropriate emphasis on training would reduce subjectivity in phenomenological identification; there would still be debate, but it is possible to achieve more consensus than there is now.

The time has come to revise the way we guide our trainees in their interest in phenomenology and emphasise the quality of phenomenological description in clinical work.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 A glossary was first included in the Present State Examination in the:

a 5th edition

b 3rd edition

c 7th edition

d 9th edition

e 10th edition.

2 Descriptive psychopathology is the study of:

a the pathological basis of psychological disorders

b the psychodynamic analysis of psychotic symptoms

c the subjective experience of the sufferings of the human mind

d the psychological basis of psychiatric illnesses

e the description of symptom development observed by a clinician.

3 A new field of psychoradiology is proposed to deal with:

a neuroradiologically led diagnosis and interpretation of treatment response in psychiatry

b use of radiology in psychosomatic disorders

c use of radiology to treat psychotic disorders

d radiology of the nervous system

e use of radiology to demonstrate structural change in the brain in psychotic disorders.

4 A patient keeps coming to his psychiatrist complaining that he worries for hours each day that his emails are being hacked into. He wants these thoughts to stop. He knows that his thoughts are illogical and out of proportion but still cannot convince himself otherwise. He is most likely suffering from:

a delusions of surveillance

b obsessive thoughts

c anxiety

d paranoia

e overthinking.

5 The phenomenological approach to psychiatry:

a delves into the aetiology of psychiatric disorders

b tries to predict the prognosis of psychiatric illnesses

c depends on the patient's possible diagnosis

d elaborates the first-person experience of the patient

e is top down in approach.

MCQ answers

1 d 2 c 3 a 4 b 5 d

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.