The scholarly and public discussion of the role of the media during elections is heated and ongoing. In the United States, much attention has been paid to the role of political advertising in either mobilizing or demobilizing the electorate.Footnote 1 In other parts of the world, where legal restrictions constrain the role of advertising, most attention has been devoted to the role of the news media. The evidence is also mixed; some studies suggest that the news media plays a general mobilizing role, while others report a mixed pattern that distinguishes, for example, between the mobilizing effects of exposure to TV news and the demobilizing effects of exposure to other TV content, or between public broadcasting news and private TV news.Footnote 2

Previous research has identified different content features of news media coverage that have the potential to either mobilize or demobilize citizens in electoral contexts. ‘Mobilizing’ media contact includes news that focuses on disagreement, conflict and differences of opinion between political actors; it shows that there is something at stake and something to choose from.Footnote 3 This study focuses on the role of conflict framing in election campaign news coverage and assesses its potentially mobilizing effect on voters. We contrast this effect with the role of mere news exposure – that is, overall individual news consumption regardless of content.

We investigate the effect of news media coverage of the election on individual turnout, while controlling for many of the usual explanatory factors for turnout. To examine the role of news coverage in mobilizing the electorate over the course of a campaign, our research design combines a media content analysis of campaign news coverage with panel survey data. We focus on the impact of campaign news coverage framed in terms of conflict on voter mobilization, for which we outline our expectations below. We are interested in the conditional nature of this effect; we expect that conflict news is particularly mobilizing if voters have little evidence that there is ‘something at stake’ during the election campaign. We therefore test our expectations in a range of contexts and conduct our study in a cross-national comparative context in order to gain more analytical leverage and insights into the contextual impact.

THE MOBILIZING EFFECT OF CONFLICT NEWS FRAMING

News about politics is often framed in terms of conflict.Footnote 4 One reason for this is that conflict between political actors has high news value and attracts attention.Footnote 5 The news media tend to focus on stories in which there is conflict – where two sides can be pitted against one another.Footnote 6 The presence of conflict in a story not only signals relevance to audiences but often also serves to meet journalistic standards of critical and balanced reporting.Footnote 7 Semetko and Valkenburg define conflict news frames as emphasizing ‘conflict between individuals, groups or institutions as a means of capturing audience interest’.Footnote 8 Conflict is an essential part of democratic decision-making and is as such inherent in politics.Footnote 9 According to Schattschneider, political conflict and the competition of different ideas in public debate are defining elements of democracy and help citizens make a choice: ‘conflict, competition, organization, leadership and responsibility are the ingredients of a working definition of democracy’.Footnote 10

Conflict, typically, precedes consensus about a problem. In the US context, it has been argued that citizens react negatively to basically all political disagreement among politicians.Footnote 11 However in different contexts, and if citizens realize that it is part of democratic decision making, conflict may (in principle) have positive effects on citizens’ political attitudes and/or participation.Footnote 12 On the one hand, citizens may, for example, come to the conclusion that democracy functions well, be motivated to talk about political affairs and thus feel a greater incentive to vote. On the other hand, citizens may, in the absence of political conflict, also become less motivated to vote in elections if they feel there is very little at stake.Footnote 13

The key assumption in this study is that conflict news has the ability to mobilize voters. However, we do not expect this to take place across the board. Citizens pick up cues about the importance of elections from elites and the news environment. If voters perceive that there is nothing on offer during elections, or if there is consensus across different political parties, they might not be inspired to engage. We therefore expect that conflict framing is potentially effective in mobilizing voters as it can ‘alarm’ citizens that there is something at stake, and serves to highlight the differences between political parties and thereby add relevance (and a perception of choice) to the elections.

To study the conditional impact of conflict news in different electoral contexts, we need a comparative design with variation at both the individual level (that is, the degree of conflict news a person is exposed to) and the contextual level. The context for this study is provided by the 2009 elections to the European Parliament (EP), which are typically classified as second-order national elections; that is, both political elites and citizens believe there is less at stake, which is reflected in low campaign involvement and turnout rates.Footnote 14 In the 2009 EP elections, only 43 per cent of European citizens voted. Turnout varied considerably across countries, ranging from above 90 per cent in countries with obligatory voting (Luxembourg and Belgium) to over 70 per cent (Malta) or 60 per cent (Italy), all the way down to below 20 per cent (Slovakia) or just above 20 per cent (Lithuania and Poland). Such cross-national variation provides a particularly interesting opportunity to learn more about turnout and the factors that have an impact on electoral participation.

In recent years, the European Union (EU) has faced widespread public scepticism. Key referendums related to further EU integration have failed as a result of this, and elite contestation over the issue of Europe is increasing.Footnote 15 This suggests that the EP election campaigns in some countries might be less consensual than in others.

Previous research on the antecedents of turnout in EP elections suggests that the overall decline in turnout for EP elections may not necessarily indicate a general decrease in citizen interest and engagement, but is also a result of the gradual EU enlargement. The boost in turnout that countries commonly experience during their first EP election, and its absence at subsequent elections, partially accounts for the overall decline in turnout over time.Footnote 16 Furthermore, previous research has shown that even when political culture and structural features are taken into account, citizens from different countries turn out at different rates, suggesting that there are national differences regarding the perceived importance of EP elections.

Recent studies have called for more investigations into the role of elite cues during elections campaigns, for example the influence of election news coverage in the national print and broadcast media on voter turnout across countries.Footnote 17 Indeed, the vast majority of European citizens receive most of their information about the EU and EP elections from traditional news media such as television news and newspapers.Footnote 18 Previous research has shown that how the media present the EU affects how people think of it; that is, their support regarding specific EU policies, their perceptions of how much their own country has benefited from EU membership, and whether and what to vote for in EU referendums or EP elections.Footnote 19 Thus the extent to which the EU is featured in the news can affect public opinion formation and electoral behaviour.Footnote 20 Therefore, as most of what citizens learn about an EP election and the campaign comes from the media, it is relevant to ask what role the news media play in either mobilizing or demobilizing the electorate.Footnote 21

Recent research has shown that country characteristics affect the degree to which EP election news is framed in terms of conflict. Countries that are net contributors to the EU (that is, they pay more to the EU budget than they receive) have a higher degree of conflict framing in their news coverage. We also know that there is more conflict framing in EP election news coverage in countries with low support for the EU.Footnote 22 What conditions the impact of conflict news? One important feature to consider is the evaluation of EU institutions in the news. Given that the media portrayal of the EU generally is more negative than positive, previous research has shown that positive coverage of the EU can have more of an impact on audiences than negative coverage because positive news stands out more and draws more attention.Footnote 23 Yet while the media portrayal of the EU is negative on average, there is considerable variation across countries; it is now positive on average in thirteen countries and negative in fourteen.Footnote 24

We pursue our interest in the conditional nature of the mobilizing effect of conflict news framing by focusing on the evaluations of the EU. We expect that conflict framing more effectively mobilizes voter turnout in countries where the EU is portrayed more favourably. In positive evaluative contexts, conflict news sticks out more, especially compared to countries in which the EU is portrayed less favourably (where we do not expect an additional effect of conflict framing). Thus in the present study we expect conflict framing to have more of a mobilizing effect on voters in countries in which baseline levels of polity evaluations in media coverage are more favourable compared to countries with more negative evaluations. The current study context, the 2009 EP elections, provides a unique case of varying degrees of polity evaluations across countries to test our expectations. Based on the above considerations we put forward the following expectations:

Hypothesis 1: Exposure to campaign news coverage framed in terms of conflict mobilizes citizens to vote.

Hypothesis 2: Campaign news coverage framed in terms of conflict has more of a mobilizing effect on citizens if polity evaluations are favourable than if they are less favourable.

DATA AND METHODS

To study the conditional impact of conflict news framing on mobilization, we rely on a multi-method research design including content analysis and a two-wave panel survey. The content analysis is used to investigate how the news media in the different EU member states have covered the campaign, and the panel survey is used to assess the impact of such coverage on voter turnout.

This design enables us to assess the effect of campaign news more specifically by including the results of our media content analysis in our measure of individual news exposure with the same news outlets that are in our panel survey analysis. We analyse the content of the media outlets that are included in our panel study design and for which respondents report their individual exposure. Building in actual media content characteristics into individual exposure measures more accurately and realistically models media effects. In the current study it enables us to compare the impact of conflict framing vis-à-vis mere news exposure, regardless of any content features.

Our design is also unique in that it includes an in-depth content analysis of campaign coverage in twenty-one of the then twenty-seven EU member states and combines this analysis with panel survey data in these twenty-one countries. Thus we are able to conduct a multilevel analysis that assesses the impact of both individual- and country-level variables as well as their cross-level interaction on the mobilization of citizens in the 2009 EP elections across Europe in a single study.

Media Content Analysis

To empirically test our expectations and collect information to build into our weighted measure of news exposure in the analysis of our panel data, we rely on a large-scale media content analysis. This content analysis was carried out within the framework of Providing an Infrastructure for Research on Electoral Democracy in the European Union (PIREDEU), which is funded by the European Union's FP 7 programme.Footnote 25

Sample

The content analysis was carried out on a sample of national news media coverage in all twenty-seven EU member states.Footnote 26 We focus on news items dealing with the EU and the EP election campaign specifically. In each country we include the main national evening news broadcasts of the most widely watched public and commercial television stations. We also include two ‘quality’ (broadsheet) and one tabloid newspaper from each country.Footnote 27 Our overall television sample consists of fifty-eight TV networks and our overall newspaper sample contains eighty-four different newspapers.

Period of study

The content analysis was conducted for news items published or broadcast within the three weeks running up to the election. Since election days varied across countries, the coding period also varied from, for example, 14 May–4 June for some countries up to 17 May–7 June for others.

Data collection

For television news coverage, all news items were coded; for newspapers, all news items on the title page and on one randomly selected page – as well as all stories pertaining particularly to the EU and/or the EU election on any other page of the newspaper – were coded.Footnote 28 A total of 48,982 news stories were coded in all twenty-seven EU-member countries, 19,081 of which were about the EU (10,446 dealt specifically with the EU election).Footnote 29 The unit of analysis and coding unit was the distinct news story.

Coding procedure

Coding was conducted by fifty-eight coders at two locations, the University of Amsterdam (The Netherlands) and the University of Exeter (UK). Coders were trained and supervised, and the coder training included repeated tests of intercoder reliability, which yielded satisfactory results (reported below).Footnote 30

Measures

Conflict framing

We coded the presence of conflict framing in news specifically dealing with the EU and the EP elections. A conflict frame was considered to be present in a news story when it mentioned (1) two or more sides of a problem or issue, (2) any conflict or disagreement, (3) a personal attack between two or more actors or (4) an actor's reproaching or blaming another (see online Appendix B for exact wording). The four items were coded as present (1) or not (0) and the scores were summed up and divided by the number of items to build an additive index scale reaching from 0 (minimum) to 1 (maximum) (M = 0.28, SD = 0.29).Footnote 31

Panel Survey

The data for this study come from the 2009 European Election Campaign Study.Footnote 32 A two-wave panel survey was carried out in twenty-one European Union member states.Footnote 33 Respondents were interviewed about one month prior to the EP elections and immediately afterwards. Fieldwork dates were 6–18 May and 8–19 June 2009. The survey was conducted using Computer Assisted Web Interviewing.Footnote 34

Country sample

The fieldwork was co-ordinated by TNS Opinion in Brussels and involved TNS subsidiaries in each country. All subsidiaries comply with ESOMAR guidelines for survey research. A total of 32,411 respondents participated in Wave 1 and 22,806 respondents participated in Wave 2. On average, 1,086 respondents per country completed the questionnaires in both waves, varying from 1,001 in Austria to 2,000 in Belgium. In Belgium, 1,000 Flemish respondents and 1,000 Walloon respondents completed both waves of the survey. In each country, a sample was drawn from TNS databases. These databases rely on multiple recruitment strategies, including telephone, face to face and online recruitment. Each database consists of between 3,600 (Slovakia) and 339,000 (UK) individuals. Quotas (on age, gender and education) were enforced in sampling from the database. The average response rate was 31 per cent in Wave 1 and the re-contact rate was on average 80 per cent in Wave 2.Footnote 35 The samples show appropriate distributions in terms of gender, age and education compared to census data. As we are mostly interested in the underlying relationships between variables, we consider the deviations in the sample vis-à-vis the adult population less problematic, and we exert appropriate caution when making inferences about absolute values.Footnote 36

Questionnaire and translations

The questionnaire was developed in English and translated into the different national languages. It was then translated back into English as an additional check of the accuracy of the translations. The translation was supervised by the research team and carried out by TNS (which also executes and translates the Eurobarometer surveys). Irregularities and problems arising from this process were resolved by deliberation.Footnote 37

Measures

The specific wording of all items and the descriptives for the variables listed below can be found in online Appendix A. We specified multilevel regression models with actual turnout (Wave 2) as the dependent variable. We controlled for turnout intention at Time 1 and assessed the impact of individual news exposure as well as country-level variables on actual turnout. This allows us to determine to what extent news can account for deviations between original turnout intention and actual turnout.

Our key dependent variable is turnout. There is a well-known turnout bias in studies that rely on self-reported measures.Footnote 38 As Duff et al. report, providing respondents with socially acceptable excuses for not voting can tackle this problem and reduce over-reporting.Footnote 39 The turnout question we are applying in our study follows the American National Election Survey and has shown to reduce over-reporting by as much as 8 per cent.Footnote 40

Dependent variable

Respondents were asked to indicate if they voted in the election and presented with different answering options to choose from if they did not cast their vote, which were later collapsed into one category for the analysis (1 = voted, 0 = did not vote).

Independent Variables

Control variables

We use a lagged term for turnout intention at Wave 1 in our model to measure changes that take place between our two panel waves.Footnote 41 This enables us to control for the level of initial turnout intention and to assess individual deviations from originally expressed intentions that occurred during the period between the two panel waves. Furthermore, we control for age, gender and education (see online Appendix A for measurement and descriptivesFootnote 42 ) and at the country level for whether or not voting is compulsory and/or if simultaneous elections are taking place,Footnote 43 both of which are expected to be associated with higher turnout levels.Footnote 44 Of course, a whole range of different country-level factors may affect turnout levels, but they are likely to be already captured by the differences in initial turnout intention that citizens of those countries expressed. Furthermore, due to the limited number of countries included in the study (twenty-one), we have to be sparse with the inclusion of variables at that level.

Furthermore, we take into account different types of contact with parties’ election campaign efforts. In particular, we assume that having more direct, face-to-face contact with a candidate running for the EP (or with a party member who is campaigning) and more mediated campaign contact (for example, through email, social network sites, telephone or direct mail contact) may both be conducive to electoral participation. Two measures are used to indicate citizens’ contact with the EP campaign. The first indicates direct, face-to-face contact with a candidate or party member either on the street or at the front door, and the second indicates mediated campaign contact through email, social network sites, telephone or direct mail. The direct campaign contact variable ranges between 0 and 2 (M = 0.14, SD = 0.39) and the mediated campaign contact variable ranges between 0 and 4 (M = 0.57, SD = 0.75).

News exposure (individual level)

Respondents indicated how many days per week, on average, they used each news outlet that was included in our media content analysis for their respective country. For the unweighted general news exposure measure, we built a simple additive exposure index (sum of number of days per week per outlet, divided by number of outlets). For the conflict news measure, we built a weighted additive index by weighing the individual exposure to each news outlet by the degree of conflict framing in each respective outlet (see online appendix A for descriptives).Footnote 45

Polity evaluations (country level)

The evaluation of the EU in a certain country is based on the tone toward the EU in all analysed media outlets. Tone is measured at the news-item level and ranges from −2 (very unfavourable) to +2 (very favourable). All news items mentioning the EU are taken into consideration, and their mean tone toward the EU is used.Footnote 46 We believe it makes particular sense to use aggregated media data as a contextual variable, since most citizens take cues from the media during EP elections.Footnote 47 Moreover, we of course control for direct, unmediated campaign experiences, as specified above.

Data Analysis

Our dataset has a multilevel structure, with individual respondents nested in countries. Our main model (Wave 2) has actual turnout as the dependent variable.Footnote 48 Since this variable is binary, we conduct three separate multilevel logistic regressions, in which we control for turnout intention at Time 1, thus assessing the differences between initial intention and actual turnout that occurred between the two panel waves. Furthermore, we include socio-demographic data and compulsory voting as additional controls in these models and the news exposure variable as our key independent variable. As we are comparing the impact of different aspects of news consumption (mere exposure and conflict framing), we first present fixed-effects models that demonstrate the main effect of our different news measures on turnout. We then consider possible cross-level interactions between our conflict news variable and polity evaluations as our country-level variable in a random-effects model.

RESULTS

As Figure 1 illustrates, the degree of conflict framing in campaign news coverage varies across countries and has been of considerable prominence in campaign news coverage (M = 0.28, SD = 0.29).Footnote 49 Averaging the degree of conflict framing per country (that is, including all news outlets in a country) yields high scores for France (M = 0.47, SD = 0.35), Austria (M = 0.45, SD = 0.28) and Malta (M = 0.45, SD = 0.34), followed by Latvia (M = 0.37, SD = 0.30), Romania (M = 0.37, SD = 0.34) and Italy (M = 0.36, SD = 0.30). Conflict framing was least prominent in Lithuania (M = 0.05, SD = 0.16), Germany (M = 0.13, SD = 0.20), Sweden (M = 0.15, SD = 0.20), Estonia (M = 0.17, SD = 0.25) and Ireland (M = 0.19, SD = 0.27). Below, we will include the outlet-specific conflict framing scores of our media content analysis in our survey measure of individual news exposure in order to assess the impact of conflict framing on voter mobilization.

Fig. 1 Level of conflict framing in campaign coverage in all twenty-seven EU member states. Note: bars indicate average level of conflict framing in media coverage in the respective EU member states.

Table 1 presents the results for a model that includes news variables for general news exposure and conflict framing. As this model shows, exposure to conflict news has a positive effect on turnout. These findings yield support for Hypothesis 1: the more an individual is exposed to news that is framed in terms of conflict, the more likely it is that (s)he will turn out to vote. The model also shows that mere news exposure has a small, but negative, effect. Thus considering actual content characteristics contributes to our understanding of the exact role of campaign news coverage. The effect of conflict news exists, controlling for the impact of both direct and mediated campaign contact – which is positive and significant, as expected – and provides a more conservative test of our hypothesis.Footnote 50 In all models, the intention to turn out as reported in Wave 1 has a strong positive influence. We also find that males, more highly educated and older people are more likely to turn out. Not surprisingly, respondents from countries that have compulsory voting or simultaneous elections are more likely to vote.

Table 1 Multilevel Logistic Regression Explaining Turnout in 2009 EP Elections (Wave 2)

Note: B's are unstandardized coefficients from fixed-effects multilevel models. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (one-tailed); N = 21,776.

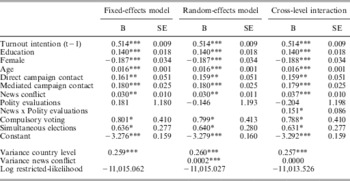

We now assess whether the effect of conflict framing differs across countries. We expect it to vary across countries with different degrees of polity evaluations in a country's general information environment. The first model presented in Table 2 resembles the model in Table 1; however, the model in Table 2 includes conflict news (but not mere news exposure) in light of previous findings. The size of the effect of conflict framing decreases substantially in Model 1 of Table 2 compared to the analysis reported in Table 1 (0.030 compared to 0.073), due to the substantial correlation between the conflict framing variable and the mere exposure variable (r = 0.89). This high correlation is not surprising, since the conflict framing variable is partly based on the reported exposure of individual respondents. In Model 2, Table 2, we estimate the same model using a random-effects instead of a fixed-effects specification, which allows the effect of conflict framing to vary across countries. The results are largely similar to the previous model, and we find that there is indeed significant variation of the effect of conflict framing across countries, though this variation is small. The third and final model in Table 2 tests our second hypothesis: does the effect of conflict framing depend on EU polity evaluation in a given country?

Table 2 Multilevel Logistic Regression Explaining Turnout in 2009 EP Elections (Wave 2)

Note: B's are unstandardized coefficients from multilevel models. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (one-tailed); N = 21,776.

The results support the hypothesis: the positive interaction term indicates that the more favourable EU polity evaluations are in a country, the larger the impact of conflict framing on mobilizing citizens to vote. The effect is significant at the 0.05 level, and the model improvement is significant. Additionally, the variance in the effect of conflict framing across countries is now not significantly different from zero anymore. Figure 2 provides insight into predicted probabilities for different levels of conflict framing (ranging from its minimum to its maximum) and polity evaluations (most negative, mean, most positive).

Fig. 2 Predicted turnout probabilities for different levels of conflict news, by degree of polity evaluation in a country. Note: other variables and variances are held constant at existing values closest to the mean. Respondent is assumed to be male and answered ‘4’ on the probability to turn out to vote variable in Wave 1. Negative polity evaluation is −0.26 (the score of Austria on that variable), mean polity evaluation is −0.04 and positive polity evaluation is +0.12 (resembling the score of Spain on that variable). Prediction is based on the fixed part of the analysis.

The figure illustrates the considerable differences in the mobilization of citizens to vote in the elections for respondents who are exposed to more (or less) positive (or negative) news about Europe – those living in countries in which polity evaluations are most positive show the lowest turnout, and those living in countries in which polity evaluations are most negative show the highest turnout. This gap closes quickly when exposure to conflict framing increases, meaning that conflict framing indeed has a mobilizing effect on voters in countries in which EU polity evaluations are most positive, and more so than in countries in which EU polity evaluations are more negative.

CONCLUSION

The media's ability to mobilize voters during a campaign is a core issue in research on electoral behaviour and political communication. The present study investigates the impact of campaign news coverage on turnout in the 2009 EP elections. We demonstrate that exposure to conflict framing in the news mobilized voters to turn out and vote in these elections, and that this effect was more pronounced in countries in which EU polity evaluations are comparatively positive.

We draw three kinds of conclusions from this study. We first learn about conflict news and voters in general, about the mobilizing effect of conflict in EP elections in particular and about the importance of contestation over EU issues. The first lesson is that conflict-driven news is not only a natural and almost inherent feature of election campaigns. It can also be a mobilizing feature. This is important because much of the current thinking goes in the opposite direction. In a European context, Kleinnijenhuis, van Hof and Oegema, for example, showed that exposure to conflict-oriented news – that is, news ‘in which a politician of a certain party is criticized or supported by another actor or in which a politician of a certain party criticizes or supports another actor’ – leads to distrust, which in turn depresses turnout.Footnote 51 In line with De Vreese and Tobiasen, we argue the opposite: that conflict news, including potential controversies, shows an electorate that there is an actual political choice to be made – and this boosts turnout.Footnote 52 This dovetails with the conclusions by van der Eijk and Franklin that ‘informative election campaigns, that is, campaigns that help people perceive what contending political parties and candidates stand for, promote turnout’.Footnote 53 It also resembles the argument made by Zaller and his burglar alarm metaphor, builds on Converse and is similar to Schudson's concept of the ‘monitorial citizen’. He argues that citizens cursory examine the news and – if need be – the media will ‘alarm’ citizens (even the inattentive) to be informed about major issues.Footnote 54 The ‘induction’ of conflict in a positive evaluation environment might be such a burglar alarm – a cue to citizens that there is something at stake and something to choose between. Future studies should further invest in explicating the exact mechanisms that explain how conflict framing can stimulate electoral participation. We assume that conflict news increases the perception of an election's relevance, however other simultaneous influences might also be at work. Furthermore, if conflict matters for turnout, another interesting question is which factors influence the prominence of conflict framing in political news coverage to begin with. Research explaining media content is only just emerging, however it has recently been shown that conflict framing in election news is more prominent in certain media outlets (broadsheets and public broadcasting) and political systems (proportional representation) and depends on other factors such as public opinion on relevant issues or the co-occurrence of simultaneous elections.Footnote 55 Finally, our findings also support the claim made by us and others that conflict is a natural feature of democracy, which allows for a more nuanced view than before. Now we can say, more specifically, that levels of conflict vary in important – and, as the analysis shows – consequential ways between media and (democratic) countries and thus play a different role in different contexts.

Secondly, we learn about the alleged democratic deficit of the EU and the growing detachment of European citizens from the Union. Our findings suggest that conflict framing in the news might be part of the solution rather than the problem. Conflict mobilizes and contributes to the politicization of EP elections, which have formerly been seen as mere second-order national contests, ruled by domestic considerations. As argued above, conflict has the potential to flag an election as salient to voters, and indicate that there is something at stake. This is particularly relevant in political systems with a multilevel system of governance, such as the EU, where citizens feel further removed from politics and political decision making. We argue, from a normative viewpoint, that conflict is good for democracy and can have positive effects on citizen participation, as demonstrated in this study.

The third lesson to be taken from this study concerns the more fundamental idea about contestation over European integration. While issues of European integration have long belonged to the category of ‘permissive consensus’, this is no longer the case. Hooghe and Marks convincingly argue that permissive consensus has been replaced by constraining dissensus.Footnote 56 They argue that European integration has become politicized in elections and – consequently – the role played by citizens has become more important in the trajectory of European integration. Relating this to the media's role during elections, we can conclude that when the news media frame European elections in terms of conflict, they contribute to the politicization of Europe, which is conducive to turnout in these elections. It also helps change the nature of these elections, since increased conflict makes the elections less automatic ‘second-order national elections’. De Vries et al. have shown that European issues are more influential in campaigns where Europe is salient.Footnote 57 And when European issues are salient, this can boost the electoral support of Eurosceptic parties.Footnote 58 Contestation thus puts pro-European political leaders in a tough spot: the quality of democratic processes may improve (elections are more vivid and turnout is higher), but the outcome might be a less integration-enthusiastic EP. Conversely, contestation can be a welcome platform on which anti-European political leaders can campaign. These consequences, however, are well beyond the scope of this article.

To what extent are the results we report (not) EP campaign specific? Although we can only speculate on this question at this point, we believe that the dynamic we show is not tied to an EP election context specifically, and may generally apply in other contexts. In fact, the conditional nature of the effect we demonstrate provides some guidance in this respect. As we show, the impact of conflict news depends on context characteristics; therefore it is more likely to be influential when conflict news stands out as more novel or unusual. Thus in certain countries – such as the United States – with polarized political discourse (in which conflict is the norm, rather than the exception), conflict news could be expected to be less effective in mobilizing voters. In countries with a tradition of consensus politics, or new democracies in transformation from government-controlled to more liberal media systems, we can expect the impact of conflict news to be most pronounced.

We acknowledge several shortcomings in our study. First, we report Krippendorff's alpha scores for our content analytic indicators. Compared to other measures, these provide a rather conservative reliability test and are likely to underestimate reliability when applied to dichotomous variables with limited variance and/or uneven distribution.Footnote 59 Furthermore, while the number of coders does not directly affect reliability scores, it has the potential to do so indirectly with regard to the practical challenges a comparative research project like ours inevitably faces.Footnote 60 The media content analysis that the data for this study are derived from spanned over twenty-one countries and involved coders with nineteen different native languages. Coder training was conducted in English, and reliability had to be tested on English-language material (even though coders subsequently continued to more comfortably code their own language material as part of the full sample coding) in two sub-groups of coders at different locations. These practical challenges were dealt with to the best of our ability (for example, identical coder trainers at both locations) to provide the basis for such a comparative research project. To our knowledge, the scope of the current media content analysis is unprecedented in a European election context. The considerable efforts that were undertaken to assure reliable results are documented in this article and in greater detail in the official data documentation report.Footnote 61 In light of these considerations, we still fully acknowledge the limitations in terms of the reliability scores we report.

Secondly, we specifically assess the degree of conflict framing within news about the EU and/or the EP election campaign. However, our content analytic indicators build on previous research and are generic (not EU specific). Thus we cannot be entirely certain of the extent to which such conflict is about the EU specifically. However, since we look at conflict framing in EP election coverage specifically and assess the degree of conflict framing for stories in which the EU features centrally, there is a link between the concept of conflict framing and our key focus, the EP elections, since conflict items within campaign/EU news are relevant for the EU.

These limitations notwithstanding, our findings contribute to the discussion of the role of the news media in election campaigns and their conditional impact on voter mobilization. The study combined a media content analysis with panel survey data in twenty-one of the then twenty-seven EU member states to assess media effects on voter mobilization. Methodologically, it represents a contribution to existing investigations of the media's role in elections. Future research should consider the contents of campaign news coverage as an important factor in explaining cross-country variation in election turnout. It should also take into account the fact that the same content can have different effects in different contexts.